Abstract

Background

Corrosion is a threat to material strength and durability. Electron-rich organic inhibitor may offer good corrosion mitigation potentials. In this work, anti-corrosion potentials of nine derivatives of 1H-indene-1,3-dione have been investigated using density functional theory (DFT) approach and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. Chemical reactivity descriptors like energies of lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO), highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO), electron affinity (A), ionization potential (I), energy gap (ΔEgap), global hardness (η), global softness (σ), electronegativity (χ), electrophilicity (ω), number of transferred electrons (ΔN) and back-donation (ΔEback-donation) were computed at DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d) theoretical level. The local reactive sites and the charge partitioning on the compounds were studied using Fukui indices and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface analysis. The adsorption behavior and the binding energy of the inhibitors on Fe (110) surface in hydrochloric acid solution were investigated using MD simulation.

Results

The high chemical reactivity, kinetic instability and good corrosion inhibition potentials demonstrated by the inhibitors are rationalized based on their high EHOMO, A, σ, ΔN, ΔEback-donation, and low ΔEgap, ELUMO, I and η. A wide difference of approximately 2.4–3.2 eV between the electronegativities of iron and the 1H-inden-1,3-diones suggests good charge transfer tendency from the latter to the low-lying vacant d-orbitals of iron. The heteroatoms (O and N) and the aromatic moieties are the nucleophilic sites on the inhibitors for effective adsorption on the metal surface as shown by condensed Fukui dual functions and MEP analysis. The MD simulation shows good interaction and strong binding energy between the inhibitor and Fe (110) surface.

Conclusions

Effective surface coverage and displacement of H3O+, Cl− and water molecules from Fe (110) surface by the inhibitors indicate good corrosion inhibition properties of the inden-1,3-diones. 2-((4,7-dimethylnaphthalen-1-yl)methylene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione display low energy gap, strongest binding interaction and most stabilized iron-inhibitor configuration, hence, the best anti-corrosion potential.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Metal surface protection from corrosion is a major concern in metallurgical industries, oil factories, environment and chemical plants. Corrosion of metals is a chemical and electrochemical reaction that occurs when metal surfaces are exposed to acidic environment such as in acidic pickling, oil well acidizing and industrial cleaning [1]. Destruction of metals and materials leads to degradation of mechanical properties which, consequently, leads to direct loss of materials strength, reduction in thickness and failure of the material [2, 3]. This failure of operating equipment and material properties due to corrosion results into an increase in production and maintenance cost and breaking down of operating equipment. The consequences of corrosion are tremendous ranging from health effect, economic effect and safety to environmental outlooks [4, 5].

Although corrosion is a natural process and cannot be completely eliminated, it can be extensively reduced by adopting some methods. The method of corrosion control adopted by many industries includes material selection, rational design, cathodic protection and the use of chemical inhibitors [6,7,8]. Among the methods adopted for controlling corrosion, the use of chemical inhibitors has been one of the most practical and economical methods in combating corrosion [9]. Inhibitors mitigate corrosion by adsorbing onto the metal surface and impeding the anodic and/or cathodic electrochemical reactions occurring at the metal-medium interface [10, 11]. Corrosion inhibitors can be divided into organic and inorganic corrosion inhibitor [12]. Organic inhibitors are preferably used over inorganic inhibitors due to their cheap availability and also, they are less toxic compare to inorganic inhibitors [13]. Organic inhibitors with heterocyclic organic structures containing pi conjugated structure and heteroatoms, like N, S, O and P, capable of adsorbing on the metal surfaces via physisorption or chemisorption adsorption, are often being most effective [14]. Commonly adopted corrosion inhibitors are organic compounds including imidazolines, azoles, Schiff bases, amines and their derived salts [15,16,17].

Arylidene-indane-1,3-diones are crucial category of organic compounds with several potential applications in materials science to medical field [18,19,20,21,22]. Arylidene-indane-1,3-dione derivatives possess antibacterial, anti-coagulant and anti-diabetes properties [23]. Their applications have also been reported in electroluminescent devices, optoelectronics, eye lens clarification agents and nonlinear optical devices [18, 24, 25].

Pluskota et al. [21] synthesized some 2-arylidene-indan-1,3-dione derivatives and checked their drug-like properties [26]. However, the electron-rich structure of these organic systems owing to the presence of π-conjugation and heteroatoms has attracted our group to investigate the corrosion inhibitive potential of these compounds in progress of our research efforts to discover organic molecule with high corrosion inhibition potential.

Computational approaches such as DFT and MD simulations are considered to be effective, versatile and trending methods of designing and rationalizing corrosion inhibition properties of small to large systems [27,28,29]. The computational method provides insight into the reactivity parameters of a molecule and the relationship between these parameters and corrosion inhibition efficiency [30]. Also, MD simulations provide insight into the orientation, adsorption and binding energy of the inhibitor molecules on metallic surface [31]. Understanding the relationship between corrosion inhibition potentials, molecular structure and adsorption mechanism of organic compounds helps in improving on exist inhibitors and/or designing new functional ones. Therefore, this work was aimed at investigating the corrosion inhibition potential of 2-(4-(substituted)arylidene)-1H-indene-1,3-dione derivatives via density functional theory and molecular dynamic (MD) simulation. The adsorption, orientation and interactions of nine indene-1,3-diones corrosion inhibitors on Fe (110) surface in hydrochloric acid solution were studied using MD simulation.

2 Methods

2.1 Density functional theory (DFT) studies

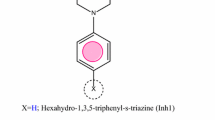

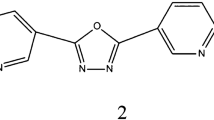

DFT is a computational tool used to predict the electronic structure of a compound. The optimization of 2-arylidene-indan-1,3-dione derivatives (Fig. 1) was done by employing DFT technique with B3LYP functional and 6-31G(d) basis set after initially running the conformal distribution to obtain the most stable conformal (lowest energy conformal) using molecular mechanics force field (MMFF) [32]. This level of theory has been described to be consistent with experimental findings [29]. The frontier molecular orbital (FMO) energies such as highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO), energy gap, ∆Egap (Eq. 1), electron affinity, A (Eq. 2), ionization potential, I (Eq. 3), electronegativity, χ (Eq. 4), chemical potential, CP (Eq. 4), chemical hardness, η (Eq. 5), softness, σ (Eq. 6), global electrophilicity index, ω (Eq. 7) and the back-donation (Eq. 8) were calculated [33,34,35]. All quantum chemical calculations were carried out using the Spartan 14 software program.

Furthermore, the charge transfer between the corrosion inhibitor and the metal is driven by the difference in their electronegativities (and chemical potentials) when they are in contact until a balance in chemical potential is attained [36]. The number of electrons transferred (ΔN) is calculated using Eq. 9.

The Fukui analysis plays an important role in predicting the site of nucleophilic and electrophilic attack [37]. The partial atomic charge is defined by qk(N+1) when a molecule accepts electron and by qk(N-1) when it loses an electron. For a neutral molecule, the charge on each atom is defined by qk(N). The nucleophilic, electrophilic and dual Fukui parameters were calculated using Yao’s dual descriptors as shown in Eqs. 10, 11 and 12, respectively.

2.2 Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed on all compounds under consideration to probe their interactions with iron surface using the Forcite module in the BIOVIA Materials Studio 2017. The simulation was carried out in a box of dimension (24.82 Å × 24.82 Å × 38.11 Å) with periodic boundary conditions consisting of six layers of cleaved iron Fe (110) expanded into a 10 × 10 supercell. The Fe (110) plane is considered the most stable iron surface because it is densely packed [38]. A 30 Å vacuum layer was directly placed above the iron surface and filled with each inhibitor compound and 290 H2O, 10 H3O+ and 10 Cl- molecules to replicate a real corrosive medium. The Condensed-phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies (COMPASS) force field was employed to perform geometry optimization on all component structures in the box. Molecular dynamic simulations were performed in a Nose-Hoover thermostat using NVT canonical ensemble at 298 K at a time step of 1 fs and a simulation time of 300 ps. The energy of interaction, Einteraction of the compounds with the metal surface was obtained using Eq. 13:

where Etotal is the single point energy of all components in the simulation box, EFe+solution is the energy of iron (110) surface and the corrosive medium and Einhibitor is the single point energy of the inhibitor. The binding energy (Ebinding) is given by Eq. 14 [39]:

3 Results

3.1 Quantum chemical calculations, HOMO, LUMO and MEP surface analyses

Recently, DFT has become a powerful tool in predicting effective organic corrosion inhibitors [40, 41]. Some quantum chemical parameters of a compound have been established to relate the corrosion inhibition efficiency with the molecular properties [42]. These quantum chemical parameters were used to correlate the corrosion inhibition potentials of nine 2-arylidene-indan-1,3-diones with the structural variations. The results of quantum chemical calculations of 2-arylidene-indan-1,3-diones are summarized in Table 1.

The optimized structures of the corrosion inhibitors are shown in Fig. 2a. The HOMO and LUMO surfaces are shown in Fig. 2b and c, respectively. The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps of the corrosion inhibitors are shown in Fig. 3. The MEP surface represents the local regions on the organic systems that are susceptible to nucleophilic attack (blue region) and electrophilic attack (red, orange, yellow and green region) [43].

3.2 Fukui indices

The Fukui indices and the Mulliken charge distribution describe the local reactive sites of an organic system that are susceptible to either nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks. Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 show selected Fukui indices (fk+, fk− and ∆fk) and Mulliken charges for the anionic, neutral and cationic forms of the corrosion inhibitors 1 to 9. The Mulliken charges depict asymmetric charge distribution of the atoms. Large values of the Fukui indices (fk+ and fk−) indicate molecular softness and chemically reactive sites [44]. The condensed Fukui dual descriptor (∆fk) is a more explicit and accurate parameter than fk+ and fk− for describing local reactivities [45, 46]. Atoms with positive ∆fk are susceptible to electrophilic attack while those with negative ∆fk are susceptible to nucleophilic attack [47].

3.3 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed on each compound to explore the stable configurations of the different inhibitor molecules and the interaction modes between each of them and the Fe (110) surface [48]. The method tends to imitate the real-life corrosion process of mild steel in a corrosive environment and also explore the processes relating to the corrosion inhibition behavior of the molecules on the metal [49]. The interaction and the binding energies of the inhibitors on Fe (110) surface in hydrochloric acid solution are reported in Table 1. The top and side view of the Fe (110)-inhibitor system in HCl(aq) medium is shown in Fig. 4.

4 Discussion

4.1 Discussion on DFT calculations

The energies of HOMO and LUMO are crucial quantum chemical parameters that describe the reactivity and kinetic stability of a material [50,51,52]. HOMO energy value of a molecule shows the tendency of the molecule to donate electron to low-lying vacant orbitals of a metal. Therefore, the adsorption process of a molecule on a metal surface is facilitated and increased with increase in HOMO energy (EHOMO). Hence, higher HOMO energy of a molecule enhances the corrosion inhibition potential of the molecule. On the other hand, LUMO energy (ELUMO) value of a molecule indicate the tendency of a molecule to accept electron from metal atom. Decrease in (ELUMO) shows the ability of a molecule to accept electron from a metal atom. Hence, lower LUMO energy increases the corrosion inhibition efficiency of a molecule.

The EHOMO and ELUMO calculated for the compounds are shown in Table 1. From the results, the best compounds according to the EHOMO are compounds 2, 7 and 9 (with EHOMO values of −5.37, −5.42 and −5.27 eV, respectively). The EHOMO follows the order: 9 > 2 > 7 > 5 > 8 > 6 > 3 > 4 >1. High EHOMO of compound 9 and compound 2 can be related to the presence of an effective electron-donating amine group. This indicates that compounds 2, 7 and 9 possess high tendency of donating electrons to the low-lying unfilled d-orbital of the metal atom. Also, compound 2 presents well stabilized ELUMO (−2.09 eV) with good potential of back-bond formation with the metal.

The ionization potential (I) and electron affinity (A) depict the electron-donating and electron-accepting ability of the inhibitors, respectively [53]. The ease of electron donation of a corrosion inhibitor is enhanced as the ionization potential decreases. From Table 1, the corrosion inhibitors display good ionization potential which decreases in the order: 1 > 4 > 3 > 6 > 8 > 5 > 7 > 2 > 9 and follows a reverse trend with EHOMO. It could be observed that para-substitution of diphenylamine (compound 9) and dimethylamine (compound 2) on the parent structure (compound 1) significantly lowers the ionization potential possibly by destabilizing the highest filled molecular orbital. On the other hand, the electron-accepting tendency of an inhibitor increases as its electron affinity (A) increases. The A parameter is relatively high in compounds with bare phenyl and naphthalenyl substitution at 2-indene-1,3-dione position especially in compounds 1 and 6. Substitution of electron-donating groups (such as amine and methoxy moieties) on the phenyl and naphthalenyl rings decreased the electron affinity of the corrosion inhibitors possibly by destabilizing their LUMO level relative to the unsubstituted derivatives.

The energy gap (ΔEgap) and the global hardness (η) of the compounds follow the same trend. Compounds with low ΔEgap and η possess low global hardness and exhibit good anti-corrosion properties. Compounds 9 and 7 display the lowest energy gap (2.98 and 3.15 eV, respectively) and least global hardness (1.49 and 1.58 eV) which suggest their high reactivity and kinetic instability. Also, the chemical reactivity, as deduced from ΔEgap and η, will increase in the order: 9 < 7 < 2 < 6 < 5 < 8 < 4 < 3 < 1. Conversely, global softness follows a reversed trend. This trend supports the high chemical reactivity, global softness (σ), ease of electron donation and effective corrosion inhibition potentials of systems with electron-donating substituents. Similar observation has been reported in literature [54]. Interestingly, para-substitution on the benzylidene moiety of 1H-indene-1,3-dione lowers the energy gap, global hardness and improves the ionization potential, global softness, the number of electrons transferred and the back-donation properties of the organic inhibitors relative to the parent compound 1.

The electronegativity (χ) specifies the direction of flow of electron between the metal surface and the inhibitor till a balance in chemical potential is attained. On adsorption of inhibitor on the metal surface, especially iron (with electronegativity of 7 eV), electrons should be transferred from the species with lower electronegative to the one with higher electronegativity. From Table 1, all the inhibitors display less electronegativity (χ = 3.78–4.54 eV) than that of iron which suggests that they are capable of electron transfer to the metal surface. The χ follows the order: 2 < 9 < 7 < 8 < 5 < 3 < 4 < 6 < 1. The farther the χ of the inhibitor is from that of the metal, the slower the attainment of equalization of chemical potential, the better the reactivity and the greater the corrosion inhibition efficiency. This suggests that compounds 2, 9 and 7 will present good kinetic interaction with the iron surface. Also, the number of transferred electron (ΔN) is an effective quantum chemical descriptor of metal-inhibitor interactions. High ΔN suggests good interaction between the corrosion inhibitor and the iron surface. The ΔN follows an opposite trend with the energy gap, suggesting better corrosion inhibition potentials of the substituted organic systems than the parent structure (compound 1). Compound 9 displays largest ΔN indicating that it has a greater potential of releasing electron into low-lying vacant d-orbitals of the metal. Electrophilicity (ω) is a quantum chemical parameter that measures stabilization of energy as a result of maximum electron transfer between a donor and acceptor. The ω follows the trend: 2 < 8 < 7 < 3 < 9 < 4 < 5 < 1 < 6. Corrosion inhibitors with low electrophilicity exhibit good electron-releasing potential for effective interaction with and stabilization on a metal surface [55]. The back-donation character of the organic inhibitor signifies the synergistic tendency of the inhibitors to accept π-electron from the d-orbital of the iron into its vacant antibonding orbital. This property increases in the order: 1 < 3 < 4 < 8 < 5 < 6 < 2 < 7 < 9, indicating that compounds 9, 7 and 2 possess good back-bonding ability with metal surface.

Succinctly, p-methoxy and p-tolyloxy substituted inhibitors (compounds 3 and 4, respectively) display close chemical reactivity with the reference structure (compound 1), indicating little contribution of these moieties to corrosion inhibition potential while amine and dimethylnaphthalenyl moieties improved the chemical reactivity.

4.2 HOMO, LUMO and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface analyses

The HOMO and LUMO maps of compounds 1 to 9 show the distribution of the frontier molecular orbitals over the structures (Fig. 2b and c). The HOMO and LUMO of compound 1 are delocalized entirely over the structure indicating that frontier orbitals available for electron donation and reception are not essentially localized. Para-substitutions on the benzylidene moiety result in HOMO re-distribution majorly over the aryl group and partly over the indene carbon-2 suggesting the region of the compounds available for electron donation into the low-lying vacant orbitals of iron. On the other hand, the LUMO is delocalized almost over the entire molecules except on the methyl (compounds 2,3,5,7), phenyl (compounds 4 and 9) and tert-butyl (compound 8) moieties. These regions depicting the least unfilled molecular orbitals of the inhibitors are possible sites available for back-bonding with the metal surface. The molecular electrostatic potential surface analyses reveal the phenyl ring, and the oxygen atoms of the phenoxy, hydroxyl, methoxy and indene carbonyl moieties as local nucleophilic sites on the inhibitors available for adsorption on the metal surface (Fig. 3). The regions with positive electrostatic potential are the phenyl hydrogen, methyl, tert-butyl and dimethylamine moieties.

4.3 Local reactivity and Fukui descriptors

In compound 1, aromatic carbon, C11, exhibits highest fk+ and fk− indicating that it is reactive site for both electrophilic and nucleophilic attacks (Table 2). However, the highly positive ∆fk (0.029) of the carbon atom (C11) indicates that it is a preferred site for nucleophilic attack on a metal surface. The olefinic carbon bridge (C10) between the 1,3-indane-dione and the aryl moieties displays maximum negative Fukui dual function (∆fk = −0.042) indicating that it is the preferred electrophilic site. Similarly, the electrophilic center on compounds 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8 was located on olefinic carbon bridge, C10, with highly negative ∆fk as shown in Tables 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, respectively. Compounds 5 and 9, however, exhibit active electrophilic centers at indenone oxygen O2 and phenyl carbon (C14), respectively as shown in Tables 6 and 10.

The most positive ∆fk for compound 2 is on amine nitrogen, N1, while the carbon of the methyl substituent on the amine displays maximum negative ∆fk (Table 3). Although the methoxy carbon (C17) of compounds 3 and 5 shows highly positive fk+ and fk−, the positive ∆fk are localized on the heteroatoms, O3 and O4, respectively. Likewise, the maximum positive ∆fk values of 0.045 and 0.052 are observed for the naphthalenyl carbon, C11, of compounds 6 and 7, respectively (Tables 7 and 8). The dual nucleophilic reactive sites are observed at the phenyl carbon, C11 and tert-butoxide oxygen, O3 (for compound 8), and at the phenyl carbon atoms, C13 and C15 (for compound 9), respectively. In essence, the nucleophilic sites on the corrosion inhibitors are located both on the heteroatoms and the sp2-hybridized carbon atoms, while the olefinic carbon bridge majorly behaves as an electrophilic center available for possible back-bonding with the metal surface. Effective metal-inhibitor interactions enhance adsorption of the inhibitor and, consequently, the isolation of the metal from the corroding medium.

4.4 Adsorption and binding energy of iron-inhibitor system

Figure 4 represents the top and side views of the interaction of the molecules with the Fe (110) in the presence of the molecules and ions of the corrosive solvent (H2O, H3O+ and Cl−). It is noted that each of the inhibitor molecules positioned itself closer to the surface of the metal and orientating itself in a flat configuration that is partially or completely parallel to the surface after equilibration for 300 ps at 298 K. Thus, the flat configuration of the molecules ensures that the metal surface is well covered and protected from the corrosive medium [56]. This is as a result of electron-donation from active centers of the molecules, such as N, O, phenyl rings, to the d-orbitals of iron [57].

The interaction energy of each of the molecules is reported in Table 11. The negative values of the interaction energies of the molecules indicate that the interaction between them and the metal substrate is exothermic in nature. On the other hand, the binding energy of adsorption to the metal surface is the negative of the interaction energy. The more negative the interaction energy, the more positive the binding energy and the more the molecule easily adsorbs on the steel surface. From Table 11, all the corrosion inhibitors exhibit good binding affinity for the iron (110) surface in the corroding medium. Remarkably strong binding energies were obtained for compounds 2, 4, 7 and 8. However, compound 7 displays the largest binding energy compared to other selected molecules, indicating that it adsorbs most easily to the mild steel surface and provides the best protection for the surface against the corrosive chloride medium. This observation may be attributed to good structural planarity, effective back-donation tendency, high electron affinity, chemical softness of the naphthalene-based inhibitor and its proximal alignment on the iron surface (Fig. 4). Also, steric hindrance due to the diphenyl rings may hamper the iron-inhibitor interaction between the Fe (110) surface and compound 9, thereby relatively weakening inhibitor’s adsorption potential [58,59,60,61].

5 Conclusions

Corrosion inhibition potentials of nine derivatives of 1H-indene-1,3-dione have been studied using quantum chemical calculations and molecular dynamics approach. The compounds exhibit low energy gap, global hardness, ionization potential, electrophilicity and high electron affinity, global softness, back-donation and number of transferred electrons suggesting good corrosion mitigation potentials. Compounds 2, 7 and 9 display uniquely low energy gap suggesting their high chemical reactivity and kinetic instability. The electrostatic potential map and the condensed Fukui dual descriptor suggest asymmetrical charge distribution with nucleophilic reactive sites located essentially on the heteroatoms and the carbon atoms of phenyl and naphthalenyl moieties. The strong binding energy (89.93–237.83 kJ/mol) between the iron surface and the 2-(4-(substituted)arylidene)-1H-indene-1,3-diones and the effective surface coverage indicate good anti-corrosion potentials. Compound 7 (2-((4,7-dimethylnaphthalen-1-yl)methylene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione), however, exhibits strongest binding with Fe(110) surface implying its effective adsorption and good anti-corrosion potentials which may be attributed to its good affinity for the iron surface and back-donation tendency. Although 2-(4-(diphenylamino)benzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione (compound 9) possesses low energy gap and good reactivity, its effective adsorption on the iron surface is reduced possibly by steric hindrance provided by the diphenyl rings.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DFT:

-

Density functional theory

- MD:

-

Molecular dynamics

- B3LYP:

-

Becke-3–Lee-Yang-Parr

- ELUMO :

-

Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy

- EHOMO :

-

Highest occupied molecular orbital energy

- A :

-

Electron affinity

- I :

-

Ionization potential

- ΔEgap :

-

Energy gap

- η :

-

Global hardness

- σ :

-

Global softness

- χ :

-

Electronegativity

- ω :

-

Electrophilicity

- ΔN:

-

Number of transferred electrons

- ΔEback -donation :

-

Back-donation

- C P :

-

Chemical potential

- MEP:

-

Molecular electrostatic potential

- MMFF:

-

Molecular mechanics force field

- FMO:

-

Frontier molecular orbital

- fk + :

-

Nucleophilic Fukui index

- fk − :

-

Electrophilic Fukui index

- ∆fk(r):

-

Condensed dual Fukui parameter

- COMPASS:

-

Condensed-phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies

- E total :

-

Total energy of substrate-adsorbate system

- E Fe + solution :

-

Energy of iron (110) surface and the corrosive medium

- E inhibitor :

-

Energy of the inhibitor

- Ebinding :

-

Binding energy

- Einteraction :

-

Interaction energy

- compound 1:

-

2-benzylidene-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 2:

-

2-(4-(dimethylamino)benzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 3:

-

2-(4-methoxybenzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 4:

-

2-(4-(p-tolyloxy)benzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 5:

-

2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 6:

-

2-(naphthalen-1-ylmethylene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 7:

-

2-((4,7-dimethylnaphthalen-1-yl)methylene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 8:

-

2-(4-(tert-butoxy)benzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

- compound 9:

-

2-(4-(diphenylamino)benzylidene)-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione

References

Iroha NB, Dueke-Eze CU, Fasina TM, Anadebe VC, Guo L (2021) Anticorrosion activity of two new pyridine derivatives in protecting X70 pipeline steel in oil well acidizing fluid: experimental and quantum chemical studies. J Iran Chem Soc 19:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-021-02450-2

Songbo R, Ying G, Chao K, Song G, Shanhua X, Liqiong Y (2021) Effects of the corrosion pitting parameters on the mechanical properties of corroded steel. Constr Build Mater 272:121941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121941

Zolkin AL, Galanskiy SA, Kuzmin AM (2021) Perspectives for use of composite and polymer materials in aircraft construction. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 1047(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1047/1/012023

El Ibrahim B, Nardeli JV, Guo L (2021) An overview of corrosion. ACS Symp Ser 1403:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2021-1403.ch001

Conradi, (2021) Development of mechanical, corrosion resistance, and antibacterial properties of steels. Materials 14(24):1–2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14247698

Akpoborie J, Fayomi OSI, Inegbenebor AO, Ayoola AA, Dunlami O, Samuel OD, Agboola O (2021) Electrochemical reaction of corrosion and its negative economic impact. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 1107(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1107/1/012071

Kolo AM, Yakubu A, Jibrin AA, Ibrahim A (2021) Investigation of corrosion inhibition of Zn metal in 0.1 M HNO3 by Terminalia catappa. Pharm Chem J 8(4):13–26

Dahal KP, Timilsena JN, Gautam M, Bhattarai J (2021) Investigation on probabilistic model for corrosion failure level of buried pipelines in Kirtipur urban areas (Nepal). J Fail Anal Prev 21(3):914–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11668-021-01138-2

Nduma RC, Fayomi OSI, Nkiko MO, Inegbenebor AO, Udoye NE, Onyisi O, Sanni O. Fayomi J (2021) Review of metal protection techniques and application of drugs as corrosion inhibitors on metals. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 1107(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1107/1/012023

Al-Amiery AA, Kadhim A, Al-Adili A, Tawfiq ZH (2021) Limits and developments in ecofriendly corrosion inhibitors of mild steel: a critical review. Part 1: Coumarins. Int J Corros Scale Inhib 10(4):1355–1384. https://doi.org/10.17675/2305-6894-2021-10-4-1

Kadhim A, Betti N, Shaker LM (2022) Limits and developments in organic inhibitors for corrosion of mild steel : a critical review (Part two: 4-aminoantipyrine). Int J Corros Scale Inhib 11(1):43–63. https://doi.org/10.17675/2305-6894-2022-11-1-2

Abdel-Karim AM, El-Shamy AM (2022) A review on green corrosion inhibitors for protection of archeological metal artifacts. J Bio- Tribo-Corros 8(2):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-022-00636-6

Hanoon MM, Resen AM, Al-Amiery AA, Kadhum AAH, Takriff MS (2021) Theoretical and experimental studies on the corrosion inhibition potentials of 2-((6-methyl-2-ketoquinolin-3-yl)methylene) hydrazinecarbothioamide for mild steel in 1 M HCl. Prog Color Color Coat 15(1):21–33. https://doi.org/10.30509/PCCC.2020.166739.1095

Obi-Egbedi NO, Ojo ND (2015) Computational studies of the corrosion inhibition potentials of some derivatives of 1H-imidazo[4,5-F][1,10]phenanthroline. J Sci Res 14:50–56

Shamsa A, Barmatov E, Hughes TL, Hua Y, Neville A, Barker R (2022) Hydrolysis of imidazoline based corrosion inhibitor and effects on inhibition performance of X65 steel in CO2 saturated brine. J Pet Sci Eng 208:109235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.109235

Sabzi M, Jozani AH, Zeidvandi F, Sadeghi M, Dezfuli SM (2022) Effect of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole concentration on sour-corrosion behavior of API X60 pipeline steel: electrochemical parameters and adsorption mechanism. Int J Miner Metall Mater 29(2):271–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-020-2156-3

Tanwer S, Shukla SK (2022) Recent advances in the applicability of drugs as corrosion inhibitor on metal surface: a review. Curr Res Green Sustain Chem 5:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100227

Bogdanov G, Tillotson JP, Timofeeva T (2019) Crystal structures, syntheses, and spectroscopic and electrochemical measurements of two push-pull chromophores: 2-[4-(dimethylamino)benzylidene]-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione and (E)-2-{3-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]allylidene}-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione. Acta Crystallogr Sect E Crystallogr Commun 75:1595–1599. https://doi.org/10.1107/S205698901901329X

Wössner JS, Esser B (2020) Spiroconjugated donor-σ-acceptor charge-transfer dyes: effect of the Ï-subsystems on the optoelectronic properties. J Org Chem 85(7):5048–5057. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.0c00567

Asadi S, Mohammadi Ziarani G (2016) The molecular diversity scope of 1,3-indandione in organic synthesis. Mol Divers 20(1):111–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11030-015-9589-z

Roy S, Piradhi V (2017) Formal [2+1] annulation (spiro-cyclopropanation) reaction between sulfur ylides derived from baylis-hillman bromides and arylidene indane-1,3-dione. ChemistrySelect 2(21):6159–6162. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.201701221

Saczewski J, Paluchowska A, Klenc J, Raux E, Barnes S, Sullivan S, Duszynska B, Bojarski, AJ, Strekowski L (2009) Synthesis of 4-substituted 2-(4-methylpiperazino) pyrimidines and quinazoline analogs as serotonin 5-HT2A receptor ligands. J Heterocycl Chem 46:1259–1265. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.236

Pluskota R, Koba M (2018) Indandione and its derivatives—chemical compounds with high biological potential. Mini-Rev Med Chem 18(15):1321–1330. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389557518666180330101809

Durand RJ, Gauthier S, Achelle S, Groizard T, Kahlal S, Saillard J, Barsella A, Le Poul N, Le Guen FR (2018) Push-pull D-π-Ru-π-A chromophores: synthesis and electrochemical, photophysical and second-order nonlinear optical properties. Dalt Trans 47(11):3965–3975. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8dt00093j

Alizadeh A, Beiranvand Z, Safaei Z, Khodaei MM, Repo E (2020) Green and fast synthesis of 2-arylidene-indan-1,3-diones using a task-specific ionic liquid. ACS Omega 5(44):28632–28636. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c03645

Pluskota R, Jaroch K, Kośliński P, Ziomkowska B, Lewińska A, Kruszewski S, Bojko B, Koba M (2021) Selected drug-likeness properties of 2-arylidene-indan-1,3-dione derivatives—chemical compounds with potential anti-cancer activity. Molecules 26(17):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26175256

Sengupta S, Murmu M, Mandal S, Hirani H, Banerjee P (2021) Competitive corrosion inhibition performance of alkyl/acyl substituted 2-(2-hydroxybenzylideneamino)phenol protecting mild steel used in adverse acidic medium: a dual approach analysis using FMOs/molecular dynamics simulation corroborated experimental fin. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem Eng Asp. 617:126314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.126314

Llache Robledo D, Berner Perez B, Gonzales Guiterrez AG, Flores-Moreno R, Casillas N (2021) DFT as a tool for predicting corrosion inhibition capacity. ECS Trans 101(1):277–290. https://doi.org/10.1149/10101.0277ecst

Singh A, Ansari KR, Banerjee P, Murmu M, Quraishi MA, Lin Y (2021) Corrosion inhibition behavior of piperidinium based ionic liquids on Q235 steel in hydrochloric acid solution: experimental, density functional theory and molecular dynamics study. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem Eng Asp 623(May):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.126708

Abdelshafi NS, Sadik MA, Shoeib MA, Halim SA (2022) Corrosion inhibition of aluminum in 1 M HCl by novel pyrimidine derivatives, EFM measurements, DFT calculations and MD simulation. Arab J Chem 15(1):103459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103459

Tazouti A, Errahmany N, Rbaa M, Galai M, Rouifi Z, Touir R, Zarrouk A, Kaya S, Touhami ME, El Ibrahimi B, Erkan S (2021) Effect of hydrocarbon chain length for acid corrosion inhibition of mild steel by three 8-(n-bromo-R-alkoxy)quinoline derivatives: experimental and theoretical investigations. J Mol Struct 1244:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130976

Benhiba F, Hsissou R, Benzikri Z, Echihi S, El-Blilak J, Boukhris S, Bellaouchou A, Guenbour A, Oudda H, Warad I, Sebbar NK, Zarrouk A (2021) DFT/electronic scale, MD simulation and evaluation of 6-methyl-2-(p-tolyl)-1,4-dihydroquinoxaline as a potential corrosion inhibition. J Mol Liq 335:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116539

Akinyele OF, Adekunle AS, Olayanju DS, Oyeneyin OE, Durodola SS, Ojo ND, Akinmuyisitan AA, Ajayeoba TA, Olasunkanmi LO (2022) Synthesis and corrosion inhibition studies of (E)-3-(2-(4-chloro-2-nitrophenyl)diazenyl)-1-nitrosonaphthalen-2-ol on mild steel dissolution in 0.5 M HCl solution- experimental, DFT and Monte Carlo simulations. J Mol Struct 1268:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133738

Imran M, Rehman ZU, Hogarth G, Tocher DA, Chaudhry G, Butler IS, Bélanger-Gariepy F, Kondratyuk T (2020) Two new monofunctional platinum(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes: phenanthriplatin -type axial protection, equatorial-axial conformational isomerism, and anticancer and DNA binding studies. Dalt Trans 49(43):15385–15396. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0dt03018j

Khan SZ, Amir MK, Ullah I, Aamir A, Pezzuto JM, Kondratyuk T, Bélanger-Gariepy F, Ali A, Khan S, Rehman Z (2016) New heteroleptic palladium(II) dithiocarbamates: synthesis, characterization, packing and anticancer activity against five different cancer cell lines. Appl Organomet Chem 30(6):392–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.3445

Chermette H (1999) Chemical reactivity indexes in density functional theory. J Comput Chem 20(1):129–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19990115)20:1%3c129::AID-JCC13%3e3.0.CO;2-A

Sánchez-Márquez J (2019) Correlations between fukui indices and reactivity descriptors based on Sanderson’s principle. J Phys Chem A 123(40):8571–8582. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.9b05571

Shahraki M, Dehdab M, Elmi S (2016) Theoretical studies on the corrosion inhibition performance of three amine derivatives on carbon steel: Molecular dynamics simulation and density functional theory approaches. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 62:313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.02.010

Chen X, Chen Y, Cui J, Li Y, Liang Y, Cao G (2021) Molecular dynamics simulation and DFT calculation of “green” scale and corrosion inhibitor. Comput Mater Sci 188:110229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110229

Oyeneyin OE, Obadawo BS, Ojo FK, Akerele DD, Akintemi EO, Ejelonu BC, Ipinloju N (2020) Experimental and theoretical study on the corrosion inhibitive potentials of schiff base of aniline and salicyaldehyde on mild steel in 0.5 M HCl. Adv J Chem B 2(4):197–208. https://doi.org/10.33945/SAMI/AJCB.2020.4.4

Amoko SJ, Akinyele OF, Oyeneyin OE, Olayanju DS, Aboluwoye CO (2020) Experimental and theoretical investigation of corrosion inhibitive potentials of (E)-4-hydroxy-3-[(2,4,6-tribromophenyl)diazenyl]benzaldehyde on mild steel in acidic media. Phys Chem Res 8(3):399–416. https://doi.org/10.22036/pcr.2020.217825.1725

Oyeneyin OE, Ojo ND, Ipinloju N, James AC, Agbaffa EB (2022) Investigation of corrosion inhibition potentials of some aminopyridine schiff bases using density functional theory and Monte Carlo simulation. Chem Africa 5(2):319–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42250-021-00304-1

Oyeneyin OE, Ipinloju N, Ojo ND, Dada D (2021) Structural modification of ibuprofen as new NSAIDs via DFT, molecular docking and pharmacokinetics studies. Int J Adv Eng Pure Sci 33(4):614–626. https://doi.org/10.7240/jeps.928422

Obot IB, Macdonald DD, Gasem ZM (2015) Density functional theory (DFT) as a powerful tool for designing new organic corrosion inhibitors. Part 1: an overview. Corros Sci 99:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.01.037

Amoko JS, Akinyele OF, Oyeneyin OE, Olayanju DS (2021) Corrosion inhibitive potentials of (E)-5-((4-Benzoylphenyl) Diazenyl)-2-hydroxybenzoic acid on mild steel surface in 0.5 M HCl-experimental and DFT calculations. J Turkish Chem Soc Sect A Chem 8(1):343–362. https://doi.org/10.18596/jotcsa.821488

Martínez-Araya JI (2015) Why is the dual descriptor a more accurate local reactivity descriptor than Fukui functions? J Math Chem. 53(2):451–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10910-014-0437-7

Oyeneyin O, Akerele D, Ojo N, Oderinlo O (2021) Corrosion inhibitive potentials of some 2H–1-benzopyran-2-one derivatives- DFT calculations. Biointerface Res Appl Chem 11(6):13968–13981. https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC116.1396813981

Khadiri A, Ousslim A, Bekkouche K, Warad I, Elidrissi A, Hammouti B, Bentiss F, Bouachrine M, Zarrouk A (2018) 4-(2-(2-(2-(2-(Pyridine-4-yl)ethylthio)ethoxy)ethylthio)ethyl)pyridine as new corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1.0 M HCl Solution: experimental and theoretical studies. J Bio- Tribo-Corros. 4(4):64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-018-0179-3

Lgaz H, Salghi R, Jodeh S, Hammouti B (2017) Effect of clozapine on inhibition of mild steel corrosion in 1.0 M HCl medium. J Mol Liq. 225:271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2016.11.039

Hayat F, Zia-ur-Rehman, Khan MH (2017) Two new heteroleptic ruthenium (II) dithiocarbamates: synthesis, characterization, DFT calculation and DNA binding. J Coord Chem 70(2), 279-295.https://doi.org/10.1080/00958972.2016.1255328

Arulraj R (2022) Hirshfeld surface analysis, interaction energy calculation and spectroscopical study of 3-chloro-3-methyl-r(2), c(6)-bis(p-tolyl)piperidin-4-one using DFT approaches. J Mol Struct. 1248:131483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131483

Ojo ND, Krause RW, Obi-Egbedi NO (2020) Electronic and nonlinear optical properties of 3-(((2-substituted-4-nitrophenyl)imino)methyl)phenol. Comput Theor Chem. 1192:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2020.113050

Obi-Egbedi NO, Ojo ND (2021) Synthesis, light harvesting efficiency, photophysical and nonlinear optical properties of 3-(5-(4-hydroxybenzylideneamino)naphthalen-1-yliminomethyl)phenol: spectroscopic and quantum chemical approach. Res Chem Intermed 47(12):5249–5266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-021-04579-4

Odewole OA, Ibeji CU, Oluwasola HO, Oyeneyin OE, Akpomie KG, Ugwu CM, Ugwu CG, Bakare TE (2021) Synthesis and anti-corrosive potential of Schiff bases derived 4-nitrocinnamaldehyde for mild steel in HCl medium: experimental and DFT studies. J Mol Struct 1223:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129214

Lotfy K (2015) Molecular modeling, docking and admet of dimethylthiohydantoin derivatives for prostate cancer treatment. J Biophys Chem. 6(4):91–117. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbpc.2015.64010

Saha SK, Ghosh P, Hens A, Murmu NC, Banerjee P (2015) Density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation study on corrosion inhibition performance of mild steel by mercapto-quinoline Schiff base corrosion inhibitor. Phys E Low Dimens Syst Nanostruct 66:332–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2014.10.035

Obot IB, Obi-Egbedi NO, Ebenso EE, Afolabi AS, Oguzie EE (2013) Experimental, quantum chemical calculations, and molecular dynamic simulations insight into the corrosion inhibition properties of 2-(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)oxazolo[5,4-f][1,10]phenanthroline on mild steel. Res Chem Intermed 39(5):1927–1948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-012-0726-3

Nyijime TA, Iorhuna F (2022) Theoretical Study of 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one and 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenylprop-2-en-1-one as Corrosion Inhibitors on Mild Steel. Appl J Environ Eng Sci 8(2):177–86

Zheng T, Liu J, Wang M, Liu Q, Wang J, ChongY, Jia G (2022) Synergistic corrosion inhibition effects of quaternary ammonium salt cationic surfactants and thiourea on Q235 steel in sulfuric acid: experimental and theoretical research. Corros Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2022.110199

Assad H, Kumar A (2021) Understanding functional group effect on corrosion inhibition efficiency of selected organic compounds. J Mol Liq 344:117755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117755

Yan Y, Dai L, Zhang L, Zhong S (2018) Investigation on the corrosion inhibition of two newly-synthesized thioureas to mild steel in 1 mol/L HCl solution. Res Chem Intermed 44:3437–3454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-018-3317-0

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko for creating an enabling environment to carry out this research work.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OEO performed supervision; conceptualization; data curation; methodology; validation; visualization; software; formal analysis; roles/writing—original draft; and review and editing; NDO contributed to conceptualization; validation; formal analysis; roles/writing—original draft; and review and editing; NI performed data curation and roles/writing—original draft; EBA contributed to data curation; methodology; formal analysis; roles/writing—original draft and review; visualization; and software; AVE performed formal analysis and roles/writing—original draft. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There is no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oyeneyin, O.E., Ojo, N.D., Ipinloju, N. et al. Investigation of the corrosion inhibition potentials of some 2-(4-(substituted)arylidene)-1H-indene-1,3-dione derivatives: density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 11, 132 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-022-00313-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-022-00313-0