Abstract

Background and aims

NS5A inhibitors are an important option for treating chronic HCV-GT4 patients. Retreatments after NS5A-based DAAs failure are limited. We aimed to determine the effectiveness and safety of SOF/VEL-containing regimens for HCV retreatment after NS5A-regimen failure.

Methods

Prospective cohort study assessing the efficacy and safety of retreatment with SOF/VEL in addition to either voxilaprevir or ribavirin in patients who had failed previous NS5A-based DAA treatment. The primary outcome was SVR12. Safety and tolerability data were collected.

Results

One hundred fifty patients were included. The mean age was 53 years, 64% were male, and 50% of included patients had liver cirrhosis, with a mean FIB-4 score of 3.12 (± 2.30) and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score of 7.27 (± 0.48), and failed previous SOF/DCV + RBV, they were assigned to 24 weeks of SOF/VEL + RBV. The remaining 50% of participants had no liver cirrhosis and failed previous SOF/DCV, they were assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with SOF/VEL/VOX. Overall, SVR12 was achieved by 96% (n = 144/150) of included patients; 97.33% for SOF/VEL/VOX and 94.67% for SOF/VEL/RBV. Thirty-one patients experienced mild AEs; the most commonly reported mild AE in the SOF/VEL + RBV group was hyperbilirubinemia (n = 9) whereas in the SOF/VEL/VOX group were headache (n = 4) and vertigo (n = 4). Only one patient in SOF/VEL + RBV reported moderate treatment-related AE in the form of anemia and no reported severe AE.

Conclusion

Retreatment of non-cirrhotic patients with 12 weeks SOF/VEL/VOX and treatment of cirrhotic patients with 24 weeks with SOF/VEL + RBV after the failure of first-line NS5A-based therapy was an effective and well-tolerated treatment option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 58 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and approximately 1.5 million new infections occur each year, according to their estimates in 2022 [1]. Egypt is considered among the highest burden of cases because of its high overall population, high prevalence, or both [2].

A number of recent studies have verified the remarkable effectiveness of treating chronic HCV with direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) and the consequent notable amelioration of hepatic fibrosis [3, 4].

Although treatment with DAA has been enormously successful, there is a small percentage of patients who have not achieved sustained virological response (SVR) despite DAA treatment and therefore will require retreatment therapy. It is possible that prior exposure to the DAA may result in the selection of resistance-associated substitutions (RASs), particularly for NS5A inhibitors, and therefore the retreatment regimen may be compromised theoretically [5].

NS5A inhibitors are the most potent DAAs. However, they present relatively low barriers to resistance in comparison with other classes, such as non-nucleotide HCV NS5B inhibitors (6), Further, substitutions associated with NS5A inhibitors resistance are usually persistent for an extended period of time [6, 7].

The current international guidelines [8, 9] recommend 12 weeks of retreatment with sofosbuvir (SOF)/velpatasvir (VEL)/voxilaprevir (VOX). More than 95% of individuals who had been exposed to DAA achieved SVR with the second-generation regimen SOF/VEL/VOX, whereas RASs had no effect on the outcome of treatment. It is not clear whether ribavirin can be useful as an additional treatment in these cases of treatment failure. In patients with HCV genotype 3 and cirrhosis, SOF/VEL/VOX was slightly less efficacious, and such recommendations are based on only a small number of patients treated [10, 11].

This study aims to provide real-life data regarding the effectiveness and safety of SOF and VEL-containing regimens for retreatment of chronic HCV after NS5A inhibitors-regimen virological failure in Egyptian HCV GT4 patients.

Patient and methods

Study design

This is a prospective cohort study evaluating the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with either voxilaprevir or ribavirin for retreatment of chronic HCV-infected patients who failed treatment with sofosbuvir, daclatasvir with or without ribavirin regimen in routine clinical practice at Embaba Fever Hospital, specialized viral hepatitis treatment center, affiliated to the National Committee for Control of Viral Hepatitis (NCCVH), Cairo, Egypt.

The inclusion criteria were adults (> 18 years) with chronic hepatitis C without cirrhosis or with cirrhosis (Child A/B) who had previously failed combined therapy with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir regimen from September 2019 to September 2020. Patients who met any of the following criteria at enrollment were excluded: (1) Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score > 8, (2) platelets < 50,000/μL, (3) coinfection with HBV or HIV, (4) pregnancy, (5) hepatocellular carcinoma, except 6 months after intervention aiming at cure with no evidence of activity by dynamic imaging (CT or MRI), (6) Extrahepatic malignancy except after 2 years of disease-free interval. In the case of lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, treatment can be initiated immediately after remission based on the treating oncologist’s report.

Patients were stratified into two groups:

-

1-

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (SOF/VEL/VOX) group contains patients without cirrhosis, those patients received a fixed-dose oral tablet containing 400 mg of sofosbuvir, 100 mg of velpatasvir, and 100 mg of voxilaprevir without ribavirin once daily for 12 weeks.

-

2-

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir + ribavirin (SOF/VEL + RBV) group contains patients with liver cirrhosis and a Child score of 8 or less; they received a fixed dose oral tablet containing 400 mg of sofosbuvir and 100 mg of velpatasvir once daily plus ribavirin 200 mg tablet three tablets per day orally this regimen for 24 weeks.

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients who achieved a sustained virological response (SVR12), which is defined as HCV PCR remaining undetectable at week 12 following treatment completion. Adverse events related to the treatment were the secondary endpoint.

Measurements

Patients were assessed for baseline demographics, comorbidities, disease characteristics, prior treatments, and response types. The presence of or absence of liver cirrhosis was evaluated by liver echotexture on abdominal ultrasound and FIB-4 (< 1.45 = no or minimal fibrosis, > 3.25 = cirrhosis) and for those, with liver cirrhosis, the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score (CTP) was recorded at the start of treatment. Laboratory tests included complete blood count (CBC), liver biochemical profile, international normalization ratio, creatinine, alfa fetoprotein, and HCV PCR level.

During the treatment period and over a 12-week post-treatment follow-up, patients were evaluated every 4 weeks for clinical symptoms and adverse events with a special focus on serious adverse effects that led to hospital admissions or deaths, and severe conditions, such as HCC or the need for liver transplants. CBC, ALT, and AST were repeated every 4 weeks during the treatment period. HCV PCR level was measured at the end of treatment (EOT) visit and 12 weeks after the treatment completion visit using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan (using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV Quantitative Test, version 2.0, with a lower limit of quantification of 20 IU/ml). In terms of virological response, patients were considered “responders” if they had HCV RNA undetectable at the SVR12 time point using a sensitive quantification assay (< 20 IU) and considered “failure” if they experienced reappearance of HCV RNA at any time during or after treatment.

Adverse drug events were classified according to their severity into the following:

-

Mild adverse events: transient events didn’t interrupt treatment

-

Moderate adverse events: interrupt treatment or require hospitalization

-

Severe adverse events: death as a result of treatment when other causes of death rolled out.

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and was approved by the institutional review board. The patient consented to the registries’ storage of their anonymous data.

Statistical analysis

With a sample of 75 subjects per group, we had 80% power to detect a difference of 15% between the null hypothesis that the proportion of SVR12 in patients receiving velpatasvir is 80% in each group and the alternative hypothesis that the proportion of SVR12 among patients receiving velpatasvir is 95% based on previous literature with a significance level of 0.05 using a two-sample test of proportions. Student’s t-test was used to compare normally distributed quantitative variables, expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The median and interquartile range of variables with non-normal distributions were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test. The frequencies and percentages of categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate, and are presented as percentages and frequencies. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using the 2015 StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software, release 14 (StataCorp LP; College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient population

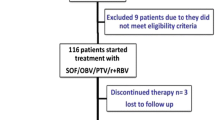

In total, 150 patients were included: 64% (n = 96) were men, the median age was 53 (± 13) years with a significantly older age of SOF/VEL + RBV group in comparison SOF/VEL/VOX group (55.07 ± 11.97 Vs. 50.53 ± 12.79, p = 0.03), 20 (13.33%) had hypertension and 35 (23.33%) had diabetes. Forty-four (29.33%) patients were smokers but none of the included patients was alcoholic or intravenous drug abuser (IVDU). All patients within SOF/VEL + RBV group had liver cirrhosis with a mean FIB-4 score of 3.12 (± 2.30) and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score of 7.27 (± 0.48). All patients had previously experienced a sofosbuvir-based interferon-free regimen with the following combinations; all patients within the SOF/VEL/VOX group had previously received sofosbuvir combined with daclatasvir whereas all patients with SOF/VEL/RBV group had previously received sofosbuvir combined with daclatasvir and ribavirin (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

At baseline, patients within the SOF/VEL/VOX group tended to have significantly better hematological and liver biochemical parameters in comparison to those within SOF/VEL/RBV group as shown in Table 2. At the end of treatment (EOT) time point, patients within SOF/VEL/VOX group showed a significant decrease in baseline hemoglobin (13.15 ± 1.33 vs. 13.75 ± 1.51, p = < 0.001), albumin levels (4.11 ± 0.45 vs. 4.27 ± 0.40, p = 0.02) and necro-inflammatory markers (ALT 32 ± 11 vs. 50 ± 36, p = < 0.001, AST; 27 ± 9 vs. 43 ± 22, p = < 0.001) and significant increase in baseline bilirubin (0.86 ± 0.24 vs. 0.71 ± 0.30, p = < 0.001). Patients received SOF/VEL + RBV showed significant decrease in baseline hemoglobin (11.39 ± 1.34 vs. 12.98 ± 1.77, p = < 0.001), ALT (34 ± 11 vs. 63 ± 36, p = < 0.001), AST (30 ± 12 vs. 77 ± 36, p = < 0.001), and bilirubin (1.02 ± 0.25 vs. 1.43 ± 0.75, p = < 0.001) and significant increase in baseline albumin (3.60 ± 0.39 vs. 3.25 ± 0.53, p = < 0.001) at EOT time-point as demonstrated in Table 3.

All patients completed therapy and achieved EOT response and were followed for 12 additional weeks. The overall sustained virological response at post-treatment week 12 (SVR12) was achieved in 96% (n = 144/150) of included patients; 97.33% (n = 73/75, 95% confidence interval 91–100%) of SOF/VEL/VOX group and 94.67% (n = 71/75, 95% confidence interval 87–99%) of SOF/VEL + RBV group, with no significant difference between both groups (p = 0.41). Characteristics of patients who did not achieve SVR12 are shown in Table 4.

Within the SOF/VEL/VOX group, only 14 (18.34%) mild adverse episodes were reported during treatment that were transient and did not interrupt treatment or require hospitalization. Headache (n = 4) and vertigo (n = 4) were the most common, followed by abdominal colic (n = 2), thrombocytopenia (n = 1), hair loss (n = 1), vomiting (n = 1), and arthralgia (n = 1). Moderate and severe adverse events were not reported in the group of patients. Within the SOF/VEL + RBV group, only a single moderate adverse event was reported in the form of anemia (hemoglobin < 8.5) that required a stop of ribavirin therapy and blood transfusion, and 17(22.67%) mild adverse episodes were reported during treatment. Hyperbilirubinemia (n = 9) was the most common, followed by anemia (n = 3), headache (n = 1), abdominal colic (n = 1), thrombocytopenia (n = 1), easy fatiguability (n = 1), and dark skin (n = 1). No reported severe treatment-related adverse events (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study included 150 chronic HCV patients who experienced virological failure to NS5A inhibitors containing anti-HCV regimen namely SOF + DCV with or without additional ribavirin. Patients were retreated with SOF + VEL with either VOX for 12 weeks or RBV for 24 weeks. Overall, 96% (n = 144/150) of included patients attained SVR12 to retreatment; 97.33% (n = 73/75) for SOF/VEL/VOX and 94.67% (n = 71/75) for SOF/VEL + RBV. The overall relapse rate was 4%; for the SOF/VEL/VOX group was 1.3% and for the SOF/VEL + RBV group was 2.7%. Among our study group, 31 patients experienced mild adverse events, 1 patient in SOF/VEL + RBV reported moderate treatment-related adverse events in the form of anemia, and no reported severe adverse events.

In Egypt, infection with HCV genotype 4 particularly subtype 4a is the most prevalent [12]. A direct-acting antiviral targets specific nonstructural viral proteins, so it disrupts viral replication [4], a successful viral eradication results in a significant reduction in liver fibrosis [3]. The overall efficacy of DCV plus SOF with or without ribavirin in treating Egyptian patients with HCV-GT4 was estimated at > 95% [13, 14]. Virus, host, and drug factors have been implicated in DAA failures. However, a causal relationship has not been established between these factors and the response to DAA [15, 16]. Generally, treatment failure is associated with the selection of HCV RASs, which are viral variants that are less sensitive to the DAA(s) used [17,18,19,20].

The frequency of RASs at the time of DAA treatment failure has been reported to range between 50 and 90% according to several studies. SOF has a high genetic barrier [21,22,23,24,25,26,27], the frequency of SOF-resistant nucleotide NS5B RASs ranges from 1 to 3%, and high-level resistant RASs disappear shortly after being introduced to the cell since these variants have high fitness costs in the absence of DAAs. As a result, these RASs quickly reverted back to the wild type since they cannot efficiently replicate. It is accepted practice to include SOF retreatment regimens after DAA virological failure, which might enhance patient response to therapy [28].

Previous exposure to NS5A inhibitors can lead to the emergence of NS5A inhibitors RASs that persist for a long period of time as they do not compromise the replication fitness [6, 7, 29, 30]. The selection of high-level resistant NS5A inhibitors RASs following DAA failure reduced the effectiveness of first-generation rescue therapy, especially in the absence of DAA classes changing [31,32,33].

In the current study, 75 patients who failed treatment with SOF/DCV were treated with 12 weeks of SOF/VEL/VOX, the SVR12 rate was 97.33% (n = 73/75). After the failure of first-generation DAA, SOF/VEL/VOX, a second-generation DAA regimen, is currently recommended for pangentopic retreatment [11, 34]. Our SVR12 rate was comparable to that reported for GT1 infected patients (222/228; 97% SVR) in POLARIS-1 and POLARIS-4 phase-II and III studies [11]. Our results align with that reported by Belperio et al. who reported an SVR12 rate of 100% for GT4 (12/12) (37, and that reported in RCT by El-Kassas et al. as an SVR12 rate of 97.9% (138/141) for intention to treat group [35].

The SVR12 rate was 94.67% (n = 71/75) in our 75 chronic HCV -GT4 patients with liver cirrhosis who failed previous SOF/DCV + RBV and were treated with SOF/VEL + RBV for 24 weeks. The addition of weight-based ribavirin to SOF/VEL in the treatment regimen of patients with compensated cirrhosis was supported by clinical trials [11, 36] and real-world studies [37,38,39,40]. Additionally, the FDA released a warning in 2019 regarding infrequent instances of hepatic decompensation, which included liver failure and fatalities in patients receiving NS3/4A protease inhibitors for CTP classes B and C. Three of these cases involved using sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir [41,42,43,44]. A clinical study on genotype 3 showed that of the 9 cirrhotic patients treated with SOF/VEL + RBV, 8 (89%) achieved SVR12 [37]. Gen et al. reported SVR12 of 83% (5/6) in GT1 and 75% (9/12) in GT3 patients treated for 24 weeks with SOF/VEL + RBV after prior NS5A inhibitors-based HCV treatment failure [38].

Twelve weeks of treatment with SOF/VEL/VOX was efficient and well tolerated, and 14 patients reported mild adverse events (headache, vertigo, abdominal colic, thrombocytopenia, hair loss, vomiting, and arthralgia). No moderate or severe adverse events were reported in this patient group.

The overall safety of SOF/VEL + RBV for 24 weeks was acceptable, only one patient reported moderate adverse event in the form of anemia, and 17 patients reported mild adverse events (hyperbilirubinemia, anemia, headache, abdominal colic, thrombocytopenia, fatigue, and dark urine) and no severe adverse events were reported. This regimen was safe and well tolerated, and ribavirin showed a safety profile consistent with what was previously known about it [39].

Limitations to this work include a small sample size and lack of bassline HCV genotype testing. However, nearly 94% of Egyptian patients with HCV are infected by HCV GT4 [40, 45, 46]. The lack of baseline RAS testing is another limitation.

Conclusion

Retreatment of non-cirrhotic patients with 12 weeks SOF/VEL/VOX and treatment of cirrhotic patients with 24 weeks with SOF/VEL + RBV after the failure of first-line NS5A inhibitors-based therapy was an effective and well-tolerated treatment option.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO Fact Sheet. Hepatitis C. Updated June 24, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c. Accessed 09 Sept 2022

Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators (2017) Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2(3):161–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30181-9. Epub 2016 Dec 16 PMID: 28404132

Soliman H, Ziada D, Salama M, Hamisa M, Badawi R, Hawash N, Selim A, Abd-Elsalam S (2020) Predictors for fibrosis regression in chronic hcv patients after the treatment with DAAS: Results of a real-world cohort study. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 20(1):104–111. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530319666190826150344. PMID: 31448717

Mohamed AA, El-Toukhy NER, Said EM, Gabal HMR, AbdelAziz H, Doss W, El-Hanafi H, El Deeb HH, Mahmoud S, Elkadeem M, Shalby HS, Abd-Elsalam S (2020) Hepatitis C virus: efficacy of new DAAs regimens. Infect Disord Drug Targets 20(2):143–149. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871526519666190121114003. PMID: 30663575

AASLD/IDSA HCV guidance panel. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Updated August 27/2020. 2020. http://hcvguidelines.org/. Cited Aug 27 2020

Yoshimi S, Imamura M, Murakami E, Hiraga N, Tsuge M, Kawakami Y, Aikata H, Abe H, Hayes CN, Sasaki T, Ochi H, Chayama K (2015) Long term persistence of NS5A inhibitor-resistant hepatitis C virus in patients who failed daclatasvir and asunaprevir therapy. J Med Virol 87(11):1913–1920. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24255

Sarrazin C (2021) Treatment failure with DAA therapy: importance of resistance. J Hepatol 74(6):1472–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.03.004. Epub 2021 Mar 12 PMID: 33716089

AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel (2018) Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 67(10):1477–1492. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy585.PMID:30215672;PMCID:PMC7190892

European Association For The Study Of The Liver (2023) Corrigendum to ’EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series’ [J Hepatol 73 (2020) 1170–1218]. J Hepatol 78(2):452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.10.006. Epub 2022 Dec 1. Erratum for: J Hepatol. 2020 Nov;73(5):1170–1218. PMID: 36464532

Sarrazin C, Cooper CL, Manns MP, Reddy KR, Kowdley KV, Roberts SK, Dvory-Sobol H, Svarovskia E, Martin R, Camus G, Doehle BP, Stamm LM, Hyland RH, Brainard DM, Mo H, Gordon SC, Bourliere M, Zeuzem S, Flamm SL (2018) No impact of resistance-associated substitutions on the efficacy of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir for 12 weeks in HCV DAA-experienced patients. J Hepatol 69(6):1221–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.023. Epub 2018 Aug 9 PMID: 30098373

Bourlière M, Gordon SC, Flamm SL, Cooper CL, Ramji A, Tong M, Ravendhran N, Vierling JM, Tran TT, Pianko S, Bansal MB, de Lédinghen V, Hyland RH, Stamm LM, Dvory-Sobol H, Svarovskaia E, Zhang J, Huang KC, Subramanian GM, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Verna EC, Buggisch P, Landis CS, Younes ZH, Curry MP, Strasser SI, Schiff ER, Reddy KR, Manns MP, Kowdley KV, Zeuzem S, POLARIS-1 and POLARIS-4 Investigators (2017) Sofosbuvir, Velpatasvir, and Voxilaprevir for Previously Treated HCV Infection. N Engl J Med 376(22):2134–2146. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1613512. PMID: 28564569

Welzel TM, Bhardwaj N, Hedskog C, Chodavarapu K, Camus G, McNally J, Brainard D, Miller MD, Mo H, Svarovskaia E, Jacobson I, Zeuzem S, Agarwal K (2017) Global epidemiology of HCV subtypes and resistance-associated substitutions evaluated by sequencing-based subtype analyses. J Hepatol 67(2):224–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.014. Epub 2017 Mar 24 PMID: 28343981

Omar H, El Akel W, Elbaz T, El Kassas M, Elsaeed K, El Shazly H, Said M, Yousif M, Gomaa AA, Nasr A, AbdAllah M, Korany M, Ismail SA, Shaker MK, Doss W, Esmat G, Waked I, El Shazly Y (2018) Generic daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, in treatment of chronic hepatitis C: real-world results from 18 378 patients in Egypt. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 47(3):421–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14428. Epub 2017 Nov 29 PMID: 29193226

Ahmed OA, Elsebaey MA, Fouad MHA, Elashry H, Elshafie AI, Elhadidy AA, Esheba NE, Elnaggar MH, Soliman S, Abd-Elsalam S (2018) Outcomes and predictors of treatment response with sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir with or without ribavirin in Egyptian patients with genotype 4 hepatitis C virus infection. Infect Drug Resist 28(11):441–445. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S160593.PMID:29628768;PMCID:PMC5878661

Buti M, Esteban R (2016) Management of direct antiviral agent failures. Clin Mol Hepatol 22(4):432–438. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2016.0107. Epub 2016 Dec 25. PMID: 28081594; PMCID: PMC5266337

Vermehren J, Dietz J, Susser S, von Hahn T, Petersen J, Hinrichsen H, Spengler U, Mauss S, Berg CP, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C (2016) Retreatment of patients who failed direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapies: real world experience from a large European hepatitis C resistance database. InHepatology 63(1 SUPP):446A-446A 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA: WILEY-BLACKWELL

European Association for Study of Liver (2015) EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2015. J Hepatol 63(1):199–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025. Epub 2015 Apr 21 PMID: 25911336

Lawitz E, Flamm S, Yang JC, Pang PS, Zhu Y, Svarovskaia E, McHutchison JG, Wyles D, Pockros P (2015) Retreatment of patients who failed 8 or 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir-based regimens with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 24 weeks. J Hepatol 62(Suppl 2):S192

Poveda E, Wyles DL, Mena A, Pedreira JD, Castro-Iglesias A, Cachay E (2014) Update on hepatitis C virus resistance to direct-acting antiviral agents. Antiviral Res 108:181–91. Epub 2014 Jun 6. Erratum in: Antiviral Res. 2014 Nov;111:154. PMID: 24911972

Pawlotsky JM (2011) Treatment failure and resistance with direct-acting antiviral drugs against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 53(5):1742–1751. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24262. PMID: 21374691

Starace M, Minichini C, De Pascalis S, Macera M, Occhiello L, Messina V, Sangiovanni V, Adinolfi LE, Claar E, Precone D, Stornaiuolo G, Stanzione M, Ascione T, Caroprese M, Zampino R, Parrilli G, Gentile I, Brancaccio G, Iovinella V, Martini S, Masarone M, Fontanella L, Masiello A, Sagnelli E, Punzi R, SalomoneMegna A, Santoro R, Gaeta GB, Coppola N (2018) Virological patterns of HCV patients with failure to interferon-free regimens. J Med Virol 90(5):942–950. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25022. Epub 2018 Feb 1 PMID: 29315640

Pisaturo M, Starace M, Minichini C, De Pascalis S, Macera M, Occhiello L, Messina V, Sangiovanni V, Claar E, Precone D, Stornaiuolo G, Stanzione M, Gentile I, Brancaccio G, Martini S, Masiello A, Megna AS, Coppola C, Federico A, Sagnelli E, Persico M, Lanza AG, Marrone A, Gaeta GB, Coppola N (2019) Patients with HCV genotype-1 who have failed a direct-acting antiviral regimen: virological characteristics and efficacy of retreatment. Antivir Ther 24(7):485–493. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP3296. PMID: 30758299

Kati W, Koev G, Irvin M, Beyer J, Liu Y, Krishnan P, Reisch T, Mondal R, Wagner R, Molla A, Maring C, Collins C (2015) In vitro activity and resistance profile of dasabuvir, a nonnucleoside hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59(3):1505–11. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.04619-14. Epub 2014 Dec 22. PMID: 25534735; PMCID: PMC4325770

Marascio N, Pavia G, Strazzulla A, Dierckx T, Cuypers L, Vrancken B, Barreca GS, Mirante T, Malanga D, Oliveira DM, Vandamme AM, Torti C, Liberto MC, Focà A, The SINERGIE-UMG Study Group (2016) Detection of natural resistance-associated substitutions by ion semiconductor technology in HCV1b positive, direct-acting antiviral agents-naïve patients. Int J Mol Sci 17(9):1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17091416. PMID: 27618896; PMCID: PMC5037695

Patiño-Galindo JÁ, Salvatierra K, González-Candelas F, López-Labrador FX (2016) Comprehensive screening for naturally occurring hepatitis C virus resistance to direct-acting antivirals in the NS3, NS5A, and NS5B Genes in Worldwide Isolates of Viral Genotypes 1 to 6. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60(4):2402–2416. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02776-15. PMID:26856832;PMCID:PMC4808155

Yang S, Xing H, Feng S, Ju W, Liu S, Wang X, Ou W, Cheng J, Pan CQ (2018) Prevalence of NS5B resistance-associated variants in treatment-naïve Asian patients with chronic hepatitis C. Arch Virol 163(2):467–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3640-6. Epub 2017 Nov 15 PMID: 29143142

Costantino A, Spada E, Equestre M, Bruni R, Tritarelli E, Coppola N, Sagnelli C, Sagnelli E, Ciccaglione AR (2015) Naturally occurring mutations associated with resistance to HCV NS5B polymerase and NS3 protease inhibitors in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis C. Virol J 14(12):186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-015-0414-1. PMID:26577836;PMCID:PMC4650141

Hézode C, Chevaliez S, Scoazec G, Soulier A, Varaut A, Bouvier-Alias M, Ruiz I, Roudot-Thoraval F, Mallat A, Féray C, Pawlotsky JM (2016) Retreatment with sofosbuvir and simeprevir of patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 or 4 who previously failed a daclatasvir-containing regimen. Hepatology 63(6):1809–1816. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28491. Epub 2016 Mar 10 PMID: 26853230

Yoshida K, Hai H, Tamori A, Teranishi Y, Kozuka R, Motoyama H, Kawamura E, Hagihara A, Uchida-Kobayashi S, Morikawa H, Enomoto M, Murakami Y, Kawada N (2017) Long-term follow-up of resistance-associated substitutions in hepatitis C virus in patients in which direct acting antiviral-based therapy failed. Int J Mol Sci 18(5):962. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18050962. PMID:28467359;PMCID:PMC5454875

Wyles D, Mangia A, Cheng W, Shafran S, Schwabe C, Ouyang W, Hedskog C, McNally J, Brainard DM, Doehle BP, Svarovskaia E, Miller MD, Mo H, Dvory-Sobol H (2018) Long-term persistence of HCV NS5A resistance-associated substitutions after treatment with the HCV NS5A inhibitor, ledipasvir, without sofosbuvir. Antivir Ther 23(3):229–238. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP3181. PMID: 28650844

de Salazar A, Dietz J, di Maio VC, Vermehren J, Paolucci S, Müllhaupt B, Coppola N, Cabezas J, Stauber RE, Puoti M, Arenas Ruiz Tapiador JI, Graf C, Aragri M, Jimenez M, Callegaro A, Pascasio Acevedo JM, Macias Rodriguez MA, Rosales Zabal JM, Micheli V, Garcia Del Toro M, Téllez F, García F, Sarrazin C, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, GEHEP-004 cohort, the European HCV Resistance Study Group and the HCV Virology Italian Resistance Network (VIRONET C) (2020) Prevalence of resistance-associated substitutions and retreatment of patients failing a glecaprevir/pibrentasvir regimen. J Antimicrob Chemother 75(11):3349–3358. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkaa304. PMID: 32772078

Dietz J, Spengler U, Müllhaupt B, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Piecha F, Mauss S, Seegers B, Hinrichsen H, Antoni C, Wietzke-Braun P, Peiffer KH, Berger A, Matschenz K, Buggisch P, Backhus J, Zizer E, Boettler T, Neumann-Haefelin C, Semela D, Stauber R, Berg T, Berg C, Zeuzem S, Vermehren J, Sarrazin C, European HCV Resistance Study Group (2021) Efficacy of retreatment after failed direct-acting antiviral therapy in patients with HCV genotype 1–3 infections. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 19(1):195-198.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.051. Epub 2019 Nov 6. PMID: 31706062

Di Maio VC, Cento V, Aragri M, Paolucci S, Pollicino T, Coppola N, Bruzzone B, Ghisetti V, Zazzi M, Brunetto M, Bertoli A, Barbaliscia S, Galli S, Gennari W, Baldanti F, Raimondo G, Perno CF, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, HCV Virology Italian Resistance Network (VIRONET-C) (2018) Frequent NS5A and multiclass resistance in almost all HCV genotypes at DAA failures: what are the chances for second-line regimens? J Hepatol 68(3):597–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.008. Epub 2017 Sep 20. PMID: 28939133

Lawitz E, Poordad F, Wells J, Hyland RH, Yang Y, Dvory-Sobol H, Stamm LM, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Landaverde C, Gutierrez J (2017) Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir with or without ribavirin in direct-acting antiviral-experienced patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 65(6):1803–1809. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29130. Epub 2017 May 3 PMID: 28220512

El-Kassas M, Emadeldeen M, Hassany M, Esmat G, Gomaa AA, El-Raey F, Congly SE, Liu H, Lee SS (2023) A randomized controlled trial of SOF/VEL/VOX with or without ribavirin for retreatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol S0168–8278(23):00234–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.011. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37088312

Bourliere M, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Tran TT, Ravendhran N, Landis CS, Hyland RH, Stamm LM, Zhang J, Dvory-Sobol H, Subramanian GM, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Serfaty L, Thompson AJ, Sepe TE, Curry MP, Reddy KR, Manns MP (2018) Deferred treatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus who were previously treated with an NS5A inhibitor: an open-label substudy of POLARIS-1. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 3(8):559–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30118-3

Esteban R, Pineda JA, Calleja JL, Casado M, Rodríguez M, Turnes J, Morano Amado LE, Morillas RM, Forns X, Pascasio Acevedo JM, Andrade RJ, Rivero A, Carrión JA, Lens S, Riveiro-Barciela M, McNabb B, Zhang G, Camus G, Stamm LM, Brainard DM, Subramanian GM, Buti M (2018) Efficacy of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir, with and without ribavirin, in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 155(4):1120-1127.e4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.042. Epub 2018 Jun 27 PMID: 29958855

Gane EJ, Shiffman ML, Etzkorn K, Morelli G, Stedman CAM, Davis MN, Hinestrosa F, Dvory-Sobol H, Huang KC, Osinusi A, McNally J, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Thompson AJ, Sulkowski MS, GS-US-342-1553 Investigators (2017) Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir with ribavirin for 24 weeks in hepatitis C virus patients previously treated with a direct-acting antiviral regimen. Hepatology 66(4):1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29256. Epub 2017 Aug 26. PMID: 28498551

Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski MS, Poordad F, Tatsch F, Pawlotsky JM (2017) Ribavirin revisited in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int 37(1):5–18

Kouyoumjian SP, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ (2018) Characterizing hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Egypt: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Sci Rep 8(1):1661. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17936-4. PMID:29374178;PMCID:PMC5785953

Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Backus LI (2019) Real-world effectiveness of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in 573 direct-acting antiviral experienced hepatitis C patients. J Viral Hepat 26(8):980–990. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13115. Epub 2019 May 10 PMID: 31012179

Da BL, Lourdusamy V, Kushner T, Dieterich D, Saberi B (2021) Efficacy of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral experienced patients with hepatitis C virus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 33:859–861

Degasperi E, Spinetti A, Lombardi A et al (2019) Real-life effectiveness and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in hepatitis C patients with previous DAA failure. J Hepatol 71:1106–1115

Llaneras J, Riveiro-Barciela M, Lens S et al (2019) Effectiveness and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in patients with chronic hepatitis C previously treated with DAAs. J Hepatol 71:666–672

Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, Brown A, Cooke GS, Pybus OG, Barnes E (2015) Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 61(1):77–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27259. Epub 2014 Jul 28. PMID: 25069599; PMCID: PMC4303918

Toyoda H (2019) Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection: Exploring new regimens. Health Sci Rep 2(3):e106. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.106. PMID:30937390;PMCID:PMC6427055

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and was approved by the institutional review board. The patient consented to the registries’ storage of their anonymous data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflct of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Omar, H., Maksoud, M.H.A., Goma, A.A. et al. Effectiveness and safety of SOF/VEL containing rescue therapy in treating chronic HCV-GT4 patients previously failed NS5A inhibitors-based DAAs. Egypt Liver Journal 14, 18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-024-00321-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-024-00321-y