Abstract

Background

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of chronic pain and disability and one of the most common conditions treated in outpatient physical therapy (PT). Because of the high and growing prevalence of knee OA, there is a need for efficient approaches for delivering exercise-based PT to patients with knee OA. A prior randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that a 6-session Group Physical Therapy Program for Knee OA (Group PT) yields equivalent or greater improvements in pain and functional outcomes compared with traditional individual PT, while requiring fewer clinician hours per patient to deliver. This manuscript describes the protocol for a hybrid type III effectiveness-implementation trial comparing two implementation packages to support delivery of Group PT.

Methods

In this 12-month embedded trial, a minimum of 16 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) will be randomized to receive one of two implementation support packages for their Group PT programs: a standard, low-touch support based on Replicating Effective Programs (REP) versus enhanced REP (enREP), which adds tailored, high-touch support if sites do not meet Group PT adoption and sustainment benchmarks at 6 and 9 months following launch. Implementation outcomes, including penetration (primary), adoption, and fidelity, will be assessed at 6 and 12 months (primary assessment time point). Additional analyses will include patient-level effectiveness outcomes (pain, function, satisfaction) and staffing and labor costs. A robust qualitative evaluation of site implementation context and experience, as well as site-led adaptations to the Group PT program, will be conducted.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the impact of tailored, high-touch implementation support on implementation outcomes when compared to standardized, low-touch support for delivering a PT-based intervention. The Group PT program has strong potential to become a standard offering for PT, improving function and pain-related outcomes for patients with knee OA. Results will provide information regarding the effectiveness and value of this implementation approach and a deeper understanding of how healthcare systems can support wide-scale adoption of Group PT.

Trial registration

This study was registered on March 7, 2022 at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT05282927).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Knee OA affects approximately 14 million people in the US [1], and the prevalence is rising [2]. Knee OA is a leading cause of chronic pain and disability [3], and it has negative impacts on many other outcomes including depressive symptoms, sleep problems, work loss, risk for cardiovascular disease, and chronic opioid use [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Veterans are at substantially greater risk for knee OA, due in part to high rates of joint injuries and activities that place excessive stress on joints [9, 10]. Within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System, arthritis is one of the most prevalent health conditions, with knee OA being the most common type [9, 11, 12].

Exercise-based physical therapy (PT) is a key component of guideline concordant knee OA management [13,14,15,16]. However, PT is underutilized for knee OA [17, 18], resulting in missed opportunities to improve outcomes for the many patients with this health condition [19,20,21,22,23,24]. A key challenge is the high demand for PT services for knee OA and limited availability of PT services within some health care settings [25]. This signals a need to develop, test, and implement efficient care models for delivering PT services for knee OA. To address this need, we conducted a RCT comparing group-based PT (Group PT) with traditional, individual PT among Veterans with knee OA [26, 27]. Group PT resulted in equivalent or greater improvements in pain and functional outcomes compared with individual PT [26]. This is important because Group PT requires fewer clinician hours per patient to deliver and therefore has the potential to improve operational efficiency and generate healthcare savings while maintaining comparable patient-level outcomes. Following the RCT, the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (DVAHCS) offered Group PT as a clinical service, and we found that patients achieved clinically relevant improvements in pain and functional outcomes that were comparable to those observed in the RCT [28].

Despite this evidence base suggesting that Group PT could improve efficiency without compromising effectiveness, there are obstacles to implementing new care models. For example, as observed in the Group PT implementation at the DVAHCS, ongoing communication and education is required across service lines when introducing a new program. In addition, providers need to be aware of the patient eligibility criteria for the program and process for submitting referrals for appropriate patients. For clinicians delivering the program, there may be challenges in learning how to deliver content in a new format (e.g., within a group setting). Therefore, scalable and efficient strategies are required to support sites in adopting and implementing new programs such as Group PT. This paper describes the protocol for a hybrid type III effectiveness-implementation trial that extends our work in studying Group PT by comparing outcomes for two different implementation support packages to promote adoption of this evidence-based program (EBP). This study is part of a larger research project being conducted at the DVAHCS, Function and Independence Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (Function QUERI); funding ID QUE:20–023.

Methods/design

Overview

The overall goal of this trial is to evaluate implementation of Group PT using activities informed by Replicating Effective Programs (REP), which has been described as both an implementation framework and strategy [29, 30]. REP was selected because of its efficiency, scalability, and flexibility to facilitate site-specific adaptations for best fit at each facility and patient population. The study involves an embedded parallel cluster RCT in which VA sites are randomized to receive one of two implementation support packages to deliver Group PT: foundational REP (“low-touch”) implementation support only (active comparator) versus enREP (experimental), which adds “high-touch” implementation support for sites that do not meet a priori benchmarks. We hypothesize that sites randomized to receive high-touch support will have superior implementation outcomes, including higher penetration, adoption, and fidelity, at 12 months. An explanatory convergent mixed method design [31] will be used to integrate qualitative data to better understand site implementation context and experience. We will also collect patient-level effectiveness outcomes to examine improvement in patient outcomes (overall and by study arm) and staffing and labor costs to conduct a business case analysis (BCA). The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) checklist is available as supplemental material [32].

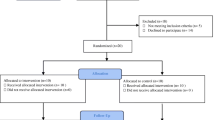

Randomization

The study will enroll a minimum of 16 VAMC sites. Because site complexity and rurality are hypothesized to affect program implementation outcomes, randomization of sites will be stratified based on these two factors. Site complexity will be determined by a VA facility-level measure that considers the complexity of services provided, with level 1a being the most complex and level 3 being the least complex; we will dichotomize complexity as high: 1a, 1b, 1c versus low: 2, 3, and small facilities/outpatient clinics with no complexity level assigned [33]. Rurality will be based on the VA Office of Rural Health rurality calculator, which uses the closest facility or county/zip code level data to determine percent of rural Veterans served; we will dichotomize rurality as high: sites serving ≥ 50% rural/highly rural Veterans versus low: sites serving < 50% rural/highly rural Veterans. We aim to enroll at least 4 rural sites. Stratified block randomization will be used, with sites randomized 1:1 to REP or enREP; all study team members will be blinded to block size except the statisticians. Randomization results will be revealed to study members 2 weeks prior to the 6-month adoption benchmark assessment. Sites are only notified of their randomization arm if they fail to meet adoption or sustainment benchmarks.

Study design

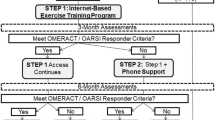

As illustrated in Fig. 1, all sites will receive a minimum “dose” of foundational support for 12 months, beginning immediately after a launch date, which serves as the beginning of the 12-month implementation period. Sites will be evaluated 6 months after launch to assess whether they meet the adoption benchmark of delivering at least one Group PT class and enrolling at least five patients (who must attend at least one Group PT class within the 6-month period). Only sites randomized to the enREP arm who do not achieve the adoption benchmark will be notified of their randomization assignment and start receiving high-touch implementation support. Otherwise, sites will continue with foundational, low-touch support only. A second benchmark assessment will occur 9 months after the launch date to evaluate program sustainment, defined as enrolling 15 new patients between months 7 and 9. Sites randomized to the enREP arm that met the 6-month adoption benchmark but do not meet the sustainment benchmark at 9 months will be notified and begin receiving high-touch support; therefore, sites in the enREP arm may receive 3 or 6 months of high-touch support.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the DVAHCS (#2334). Additionally, all quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews were reviewed by the VA Office of Labor Management Relations, which notified applicable VA national unions.

Group PT evidence-based program

Patient eligibility and enrollment

Patients will be eligible for Group PT if they have a clinician diagnosis of symptomatic knee OA and ineligible if they have a substantial fall risk or co-occurring health conditions that would make participation in a group exercise class unsafe. Patients can be referred to the Group PT program by clinicians or self-referred. Once patients are referred to Group PT, a member of the clinical delivery team will conduct an initial evaluation (in person or remotely) to determine patient appropriateness for the program and a starting point for the exercise program.

Class structure and content

Group PT was developed based on our prior work [28], best practices regarding PT and exercise for knee OA [34], and guidance from clinical partners including practicing physical therapists and VA Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Service (PM&RS) leaders with expertise in PT delivery and telerehabilitation. Sites implementing Group PT must incorporate three essential elements into program delivery: (1) six 1-h sessions with a trained clinician, including strengthening exercises and educational content, (2) offered in a group format, and (3) targeting patients with knee OA. Beyond these essential elements, sites will have flexibility in many aspects of Group PT implementation to fit their needs, including class frequency, number of patients per class (recommendation of ≤ 10), delivery mode (in-person, telehealth, or hybrid), and number of classes offered simultaneously. Each Group PT session will be approximately 1 h beginning with collecting patient outcomes, followed by warm-up and sharing “success stories”, then strengthening exercises, and ending with stretching and OA education. Strengthening exercises are organized into 5 groups, each with “challenge levels” (Table 1) and performed in five intervals, each consisting of 2 min of exercise and 1 min of rest (Fig. 2); two full rotations will be conducted per session. Group PT leaders have flexibility to adjust exercises for individual patient needs. Patients will also be instructed to perform exercises at least two times per week at home. Patients will receive a handbook with exercise guidance and educational modules as well as access to online videos to guide them through each of the exercises.

Implementation framework and strategies

Overview

Drawing from existing implementation science and organizational theory frameworks, we designed implementation support materials and activities to promote penetration, adoption, and fidelity of Group PT. Tailoring concepts from the QUERI Implementation Roadmap [35], Dynamic Sustainability Framework [36], complexity science principles, and Proctor’s taxonomy of implementation outcomes [37], our conceptual model (Fig. 3) adapted from Decosimo et al. [38] posits that implementation success is a function of interactions among Group PT intervention characteristics, contextual factors, and team function. To explain this phenomenon, complexity science postulates that the implementing team’s capacity to self-organize and communicate enables the type of problem solving and coordination required to incorporate a novel program into routine practice [39]. Consistent with these theoretical underpinnings, intervention characteristics, system-level implementation determinants (e.g., policies, regulations, and the population being served), team function, and other facets of the practice setting influence adoption and sustainment, but also vary across practice settings, and thus necessitates tailoring implementation to local context. All sites will receive foundational, low-touch implementation support to promote adaptation of Group PT to fit the clinical context in which it is being introduced. We anticipate that this will be sufficient for some but not all sites implementing Group PT. We posit that for some non-adopting sites, high-touch implementation support will be required to effectively facilitate self-organization and problem-solving to achieve improvements in implementation outcomes of interest. For an overview of activities specific to REP and enREP see Table 2.

Foundational REP implementation support (low-touch)

For this application, our low-touch approach has been conceptualized as a bundle of implementation strategies because it involves integrated yet discrete resources selected to address identified barriers to implementation success [40]. Foundational support features standardized self-guided materials, resources, and a toolkit to support implementation and site-specific adaptations. Additional details on the process of developing these materials are described in Table 2 and elsewhere [41].

Enhanced REP implementation support (high-touch)

Although an approach like REP is efficient and evidence based, it is not designed to address differences in organizational readiness or capacity to implement change, which may inhibit EBP adoption. Function QUERI addresses this potential limitation by supplementing foundational support with enhanced implementation support that is tailored to sites who do not meet Group PT program benchmarks and may benefit from extended support.

High-touch strategies feature the use of practice facilitation, defined as a multicomponent approach to improve the capacity of sites to address care quality and implementation gaps [42]. High-touch facilitation includes interactions with a trained implementation specialist (IS). Training emphasizes best practice of evidence-based implementation facilitation techniques, such as building relationships with and between others, creating an infrastructure for support and problem solving, and encouraging processes to monitor program progress [43]. Despite heterogeneity of this role in the literature, it has shown to be effective in supporting implementation for a range of programs and behavioral health interventions [44,45,46].

Sites that receive enhanced support will be engaged in one-on-one calls approximately every 3 to 4 weeks with an IS from the study team. The IS will coach individual sites using techniques, processes, and activities to help teams make decisions and identify and solve problems. Facilitators’ recommendations will be tailored to individual site’s needs and context. For example, if a site wishes to increase the number of consults being received then the facilitator will gather information about past or ongoing efforts and then suggest additional marketing and education activities.

Group PT site recruitment and onboarding

Site inclusion criteria, recruitment, and onboarding

Sites must meet the following criteria to enroll in the study: (1) clinical personnel on staff to conduct initial evaluations and lead group classes (e.g., physical therapist, PT assistant, or kinesiotherapist): this includes at least 1 primary clinician and 1 back-up clinician to cover all aspects of program delivery, (2) Offer outpatient PT service, and (3) Space to conduct group sessions (if implementing in-person Group PT classes). Sites currently offering a group class specifically for knee OA will be ineligible. Sites will be asked to commit to 12 months of Function QUERI activities, use the pre-programmed electronic health record (EHR) templates, and provide the staff necessary to implement Group PT. Site recruitment will include presentations to national and regional VA network calls and information sent through VA rehabilitation listservs. We will also identify and reach out to rural VA sites with a high volume of PT referrals to Community Care, which may signal a need for an efficient care model for delivering PT services.

We will conduct individual, virtual meetings with sites expressing interest in the program to provide an overview of program benefits, expectations, and resources provided by the Function QUERI team. Sites will be required to return participation agreements, signed by the site PM&RS Chief and a designated local point of contact (POC) for the program. Following receipt of the participation agreement, sites will provide information, via an intake form, on all personnel intending to participate in Group PT program delivery and implementation (e.g., clinicians, schedulers, supporting leadership). Sites will be onboarded in cohorts ranging in size from 5 to 7 sites with an assigned launch date. The cohort size range was selected because it is appropriate for delivering components of low-touch implementation support. On launch day, each site will receive access to the toolkit and all team members will be added to a Microsoft Teams chat group for collaboration and networking. A welcome call will be conducted shortly after the launch date to orient sites to the available resources and timeline for future activities. The Function QUERI study team will also transfer the pre-developed EHR templates for collecting patient outcomes.

Data collection and measures

All measures, descriptions, and data collection time points are detailed in Table 3.

Implementation outcomes

Implementation outcomes were selected using the taxonomy defined by Proctor and colleagues [37] and based on the overall goals of Function QUERI and operational partners. They include penetration, defined as the level of integration of a practice within a service setting, adoption, or the initial actions to employ a novel practice, and fidelity, the degree to which the program is implemented as it was designed or intended. These metrics will be assessed from the VA’s EHR [52], including Group PT-specific EHR templates.

Implementation context and experience

Semi-structured interviews

We will conduct 30-min individual or group semi-structured virtual interviews with key informants, identified on the intake form or by other team members through snowball sampling, to elicit a description of the facilitators and barriers that affected their implementation of Group PT. Specifically, we will ask about detailed activities used and any additional strategies developed during program implementation, probing for details based on Proctor’s criteria for specifying and reporting strategies (e.g., actor, action, target, temporality, frequency). We will sample 50% of sites per cohort for interviews to maximize site diversity based on implementation experience (5-point Likert from none to quite a lot) and rurality (serving ≥ 50% or < 50% rural/highly rural Veterans). We will aim to conduct 5–10 interviews per sampled site at baseline and 6 months. Only sites that receive enhanced support will be asked to participate in interviews at 12 months. All interviews will be recorded with the permission of the interviewee.

Quantitative surveys

To capture salient contextual factors related to Group PT implementation, surveys will be administered at baseline (pre-implementation) and at 12 months (post-implementation). Surveys will include validated measures (outlined in Table 3) to capture implementation process and factors influencing implementation as outlined in our overarching framework (e.g., characteristics of the intervention, site’s environmental context, and team functioning). All staff members listed on the intake form will be invited using VA REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) to complete surveys [53]. If additional program support staff are hired or identified later by the local POC then they will also be included. Each staff member will receive a survey invitation plus two reminders (3 contacts). To increase survey participation, we will offer a raffle for small prizes (< $50). Additionally, Group PT program adaptations will be reported at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months using Wiltsey Stirman’s FRAME [47], which provides a standardized way to track modifications and facilitate continual monitoring. Only the local POC will receive the adaptations form, but we will encourage teams to complete the form together. Each POC will receive a survey invitation plus two reminders (3 contacts).

Effectiveness outcomes

Effectiveness measures were selected with consideration of outcomes that are of high importance to patients with knee OA and their health care providers, as well as feasibility of administration and documentation. These measures are collected at each Group PT class and include both self-report items and physical performance tests, as shown in Table 3.

Cost data

We are also collecting two types of cost data: clinical delivery and implementation strategy costs. Within 2 weeks after a site has started offering Group PT as a clinical service, the local POC will be emailed two Excel forms to document this data. The implementation strategy form will measure time spent training and preparing for Group PT delivery during the month prior to sites offering their first Group PT class. The clinical delivery form, used to measure personnel time associated with actual Group PT delivery, will involve tracking time associated with several tasks during the first 6 weeks of program delivery. Both implementation and delivery costs will be associated with the individual who is completing each task (e.g., PTA, PT) and their salary to quantify time in monetary terms. Lastly, the cost of any purchased equipment will be documented by the local POC.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

As part of our hybrid type III effectiveness-implementation study design, the primary research question compares differences in implementation outcomes between arms. Implementation outcomes are continuous (penetration, fidelity) and binary (adoption) cluster-level outcomes, and generalized linear models will be used to examine the effect of REP versus the addition of enREP on implementation outcomes at 12 months [54]. The main predictor of interest will be REP versus enREP, with indicators for the stratification variables of complexity level and rurality included in the final model. In secondary analyses, implementation outcomes at 6 months will be assessed. We will examine how implementation outcomes change over time using descriptive methods (e.g., plots, descriptive statistics, subgroups). We will describe patient-level effectiveness outcomes overall and by study arm. We will examine how patient outcomes change over time using descriptive methods (e.g., plots) and will calculate descriptive statistics for all visits and change outcomes among patients who have data from multiple visits.

Descriptive statistics for staff survey measures related to implementation context and experience (Table 3) will be calculated overall and by study arm. We will use the same modeling approach described above to examine the effect of implementation package on survey measures. In addition, we will assess the relationship of implementation context and experience measures on implementation and effectiveness outcomes.

Qualitative analysis

We will use directed content analysis [55] that includes (1) a priori codes to indicate foundational, low-touch activities and ERIC (Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change) implementation strategies [56, 57] (e.g., “engagement with toolkit”) and or (2) data derived codes of barriers to implementation.

Integration of qualitative and quantitative data

We will summarize the coded data in a framework matrix [58] to compare reports of implementation strategies and barriers across sites and by study arm and implementation outcomes. The rows of the matrix will reflect coded implementation strategies and the columns will reflect the study arm and implementation outcomes for each site. Summaries of coded data within each matrix cell will describe the implementation strategy or barrier. The qualitative researchers will meet with the project director and other team members to review the matrix and identify patterns between sites with lower versus higher quantitatively assessed implementation outcomes.

Sample size and power

Sample size calculations were conducted for the primary implementation outcome penetration at 12 months. Using a two-sided t test based on a sample size of 16 sites (randomized 1:1 to each study arm), a type-1 error rate of 5%, we will have 80% power to detect an effect size difference of 1.5 and 90% power to detect an effect size difference of 1.7 between arms. Based on data of mean number of patients enrolling per month over a 1-year period of implementation of Group PT in Durham, we assumed standard deviations ranging from 1.5 to 2.5. Therefore, the effect size differences were powered to detect differences in mean number of patients enrolling per month between arms of 2.3 to 3.8 patients for 80% power and 2.6 to 4.3 patients for 90% power.

Business Case Analysis (BCA)

The base-case BCA will compare the expected value for costs (implementation and delivery), implementation outcomes, and effectiveness outcomes between treatment arms using site level estimates from the trial data. We will model the probabilities meeting benchmarks and associated outcomes (costs, penetration) occurring with those events using a decision tree. In the low-touch arm, sites will not receive enhanced support when benchmarks are not met, though costs of foundational support will be incurred and tracked in the model. In the high-touch arm, sites will receive enhanced support when benchmarks are not met and will incur additional implementation costs associated with enhanced support. This will allow us to compare the expected costs and penetration in the cohort of sites if all sites had received high-touch support versus not. In addition, we will use one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analysis to simulate likely outcomes in the context of distributions informed by the trial data as well as prior evidence for the EBP. By modeling plausible scenarios, the decision model will allow us to communicate a practical range of estimates to sites and operational partners rather than relying on statistical significance. Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analysis will be used to incorporate measured uncertainty in the estimates for all outcomes and generate probabilities for exceeding VA thresholds for value. We will work with our operational partners to establish thresholds for decision-making [59].

Discussion

Although there have been many RCTs of PT and exercise-based interventions for knee OA, there have been very few implementation studies in this area and none, to our knowledge, comparing different approaches to implementation support. As a result, our knowledge regarding optimal implementation activities for scaling PT interventions and care models in real-world clinical settings is limited. Our team has worked closely with clinical and operational partners on a multi-step journey to study and implement Group PT. Our initial RCT incorporated pragmatic elements that facilitated the transition to more implementation-focused work [26]. In particular physical therapists at the DVAHCS delivered the Group PT program, and it was embedded into their clinical workflow. This provided an opportunity to assess feasibility of integration into the PT Service, and physical therapists provided direct input on the practical and clinical aspects of the program. When the DVAHCS PT Service began implementing Group PT following completion of the RCT, we were able to conduct a robust evaluation of the program [28]. This evaluation led to EBP refinements and provided our team with experience in collection of both patient-reported and EHR-based outcomes in the context of Group PT delivery. These experiences with the initial Group PT RCT and the DVAHCS evaluation have led to a rigorous, partner-informed implementation trial.

There are advantages to a group-based PT model for both health systems and patients. For health systems, the efficiency and potential cost savings of Group PT are clear advantages. For a six-session round of Group PT with 10 enrolled Veterans, a PT service would provide 60 patient-hours of care with 6 h of clinician time. This represents substantial time and resource savings. For patients, use of a group-based model can improve access, particularly in health care settings that have limited PT personnel resources. Another advantage of the Group PT program is the standardized approach to delivering exercise-based PT for knee OA. We have developed this program based on research and best practices for PT and exercise for knee OA, and sites implementing Group PT have access to many ready-to-go resources for program delivery.

There are also some challenges to implementing group-based programs. First, starting a new group program requires logistical tasks such as setting up new clinics or note templates in the EHR and establishing scheduling procedures. Second, the efficiency of group programs depends on continued enrollment of patients to fill the classes. Sites therefore need plans for maintaining referrals of patients to the program. Similarly, sites need plans to minimize “no shows” to maximize program efficiency and impacts. Third, although all patients enrolled in Group PT have knee OA, they vary in terms of physical function, comorbidities, and other factors that require tailoring of the exercise approach. Although this can be a challenge to delivering PT in a group setting, we have designed Group PT with this heterogeneity in mind and provided sets of exercises appropriate for patients with different functional abilities.

This study will also yield scientific advances related to strategic tailoring of support for implementing new EBPs. Some prior studies have evaluated adaptive implementation approaches, in which sites are provided with more intensive support if they do not meet benchmarks [60,61,62]. However, research in this area is still limited. Our Function QUERI projects will provide robust evidence regarding the use of implementation intensification across three different EBPs. To our knowledge, the Group PT RCT is the first to examine a tailored implementation approach for delivering a PT-based intervention. We are collecting detailed data on adaptations to Group PT, which will enhance understanding of how sites deliver the program in a way that ensures best fit with local resources, needs, and structures. We are also collecting robust information on site-level barriers and facilitators to implementation. These data will enhance our understanding of the specific preconditions, site-level adaptations, and tailoring of support that contributes toward more widespread implementation of Group PT. Additionally, the planned analysis on the costs of each implementation strategy, while also assessing the impacts on implementation outcomes, presents a unique opportunity to provide guidance to leadership and policy makers on how to cost-effectively promote adoption and sustainment of Group PT. While implementation researchers have made notable progress in the design and testing of strategies to improve implementation, comparative economic evaluation of implementation strategies are lacking. Yet, these findings are critical for payers, policy-makers, and providers to make informed decisions on whether specific strategies are an efficient use of resources. Currently, few implementation studies include implementation cost data and even fewer compare strategies’ cost effectiveness [63].

There are some limitations to this trial. First, sites are followed for 12 months after entry into the study, and it will be important for future work to evaluate sustainment of Group PT delivery over a longer period. Second, patient outcomes are collected through the end of Group PT participation, and future work should also examine patient-level effectiveness and maintenance at later time points. Third, although we aim to recruit sites that vary in terms of geography, rurality, and facility complexity, our final sites may not be representative in all ways. In particular, participating sites may have a higher level of organizational readiness to change or other motivators that make implementation success more likely. Fourth, our study only includes VA sites, and additional work is needed to examine Group PT effectiveness and implementation in other health systems.

In summary, our Function QUERI program is poised to have significant impacts for Veterans at high risk for negative health outcomes, health systems seeking to efficiently implement EBPs and the implementation science community. The Group PT trial is addressing one of the most common, function-limiting health conditions among Veterans and older adults in general. Based on our prior work [26, 28], the Group PT program has strong potential to become a standard offering for PT Services and clinics, improving function and pain-related outcomes for patients with knee OA. This trial will take important steps toward that goal.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- VA:

-

Veterans Affairs

- PT:

-

Physical therapy

- RCT:

-

Randomized clinical trail

- VAMCs:

-

Veterans Affairs Medical Centers

- REP:

-

Replicating Effective Programs

- EnREP:

-

Enhanced REP

- DVAHCS:

-

Durham VA Healthcare System

- Function QUERI:

-

Optimizing Function and Independence Quality Enhancement Research Initiative

- EBP:

-

Evidence-based clinical program

- EHR:

-

Electronic Health Record

- PM&RS:

-

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Service

- IS:

-

Implementation specialist

- POC:

-

Point of contact

- Group PT:

-

Group physical therapy for Veterans with knee osteoarthritis

- BCA:

-

Business case analysis

References

Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Yelin EH, Hunter DJ, Messier SP, et al. Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US: impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(12):1743–50.

Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Projected state-specific increases in self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitations--United States, 2005–2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(17):423–5.

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323–30.

Menon J, Mishra P. Health care resource use, health care expenditures and absenteeism costs associated with osteoarthritis in US healthcare system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(4):480–4.

Guglielmo D, Hootman JM, Boring MA, Murphy LB, Theis KA, Croft JB, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression among adults with arthritis - United States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(39):1081–7.

Taylor SS, Hughes JM, Coffman CJ, Jeffreys AS, Ulmer CS, Oddone EZ, et al. Prevalence of and characteristics associated with insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea among veterans with knee and hip osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):79.

DeMik DE, Bedard NA, Dowdle SB, Burnett RA, McHugh MA, Callaghan JJ. Are we still prescribing opioids for osteoarthritis? J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(12):3578-82 e1.

Corsi M, Alvarez C, Callahan LF, Cleveland RJ, Golightly YM, Jordan JM, et al. Contributions of symptomatic osteoarthritis and physical function to incident cardiovascular disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):393.

Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Allen KD, Theis KA, Baker NA, Murray GR, et al. Arthritis among veterans - United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(44):999–1003.

Rivera JC, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: the primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(Suppl 1):S64–9.

Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among U.S. non-veterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs health care. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:348–54.

Yu W, Ravelo A, Wagner TH, Phibbs CS, Bhandari A, Chen S, et al. Prevalence and costs of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60:146S-S167.

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden N, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–89.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(2):149–62.

Meneses SR, Goode AP, Nelson AE, Lin J, Jordan JM, Allen KD, et al. Clinical algorithms to aid osteoarthritis guideline dissemination. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(9):1487–99.

Krishnamurthy A, Lang AE, Pangarkar S, Edison J, Cody J, Sall J. Synopsis of the 2020 US Department of Veterans Affairs/US Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline: The Non-Surgical Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(9):2435–47.

Abbate LM, Jeffreys AS, Coffman CJ, Schwartz TA, Arbeeva L, Callahan LF, et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with non-surgical osteoarthritis treatment use among patients in outpatient clinics. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(8):1141–9.

Dhawan A, Mather RC 3rd, Karas V, Ellman MB, Young BB, Bach BR Jr, et al. An epidemiologic analysis of clinical practice guidelines for non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):65–71.

Bennell KL, Hinman RS, Metcalf BR, Buchbinder R, McConnell J, McColl G, et al. Efficacy of physiotherapy management of knee joint osteoarthritis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:906–12.

Deyle GD, Allison SC, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Stang JM, Gohdes DD, et al. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise program. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1301–17.

Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:173–81.

Fransen M, Crosbie J, Edmonds J. Physical therapy is effective for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):156–64.

Jamtvedt G, Dahm KT, Christie A, Moe RH, Haavardsholm E, Holm I, et al. Physical therapy interventions for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: an overview of systematic reviews. Phys Ther. 2008;88(1):123–36.

Wang SY, Olson-Kellogg B, Shamliyan TA, Choi JY, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Physical therapy interventions for knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9):632–44.

American Physical Therapy Association Workforce Task Force. A model to project the supply and demand of physical therapists, 2010-20202012 December 18, 2012.

Allen KD, Bongiorni D, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Datta SK, Edelman D, et al. Group versus individual physical therapy for veterans with knee osteoarthritis: randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2016;96(5):597–608.

Allen KD, Bongiorni D, Walker TA, Bartle J, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, et al. Group physical therapy for veterans with knee osteoarthritis: Study design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34(2):296–304.

Allen KD, Sheets B, Bongiorni D, Choate A, Coffman CJ, Hoenig H, et al. Implementation of a group physical therapy program for Veterans with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):67.

Kilbourne AM, Abraham KM, Goodrich DE, Bowersox NW, Almirall D, Lai Z, et al. Cluster randomized adaptive implementation trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation intervention to improve uptake of an effective re-engagement program for patients with serious mental illness. Implement Sci. 2013;8:136.

Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42.

Creswell JWCV. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2017.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e013318.

Administration VH. Facility procedure complexity designation requirements to perform invasive procedures in any clinical setting Washington, DC2020. Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjF8L6J3M_9AhXbmWoFHTmyDzoQFnoECCQQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.va.gov%2Fvhapublications%2FViewPublication.asp%3Fpub_ID%3D8365&usg=AOvVaw35PHE8g_U0JQCSXJ-MhWC1. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Holden MA, Metcalf B, Lawford BJ, Hinman RS, Boyd M, Button K, et al. Recommendations for the delivery of therapeutic exercise for people with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis. An international consensus study from the OARSI Rehabilitation Discussion Group. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2023;31(3):386–96.

Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, Miake-Lye I, Braganza MZ, Bowersox NW. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative Implementation Roadmap: Toward Sustainability of Evidence-based Practices in a Learning Health System. Med Care. 2019;57(10 Suppl 3):S286–93.

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Decosimo K, Drake C, Coffman CJ, Sperber NR, Tucker M, Hughes JM, et al. Implementation intensification to disseminate a skills-based caregiver training program: protocol for a type III effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):97.

Olsson A, Thunborg C, Bjorkman A, Blom A, Sjoberg F, Salzmann-Erikson M. A scoping review of complexity science in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76:1961–76.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC psychology. 2015;3:32.

Hughes JM, Zullig LL, Choate AL, Decosimo KP, Wang V, Van Houtven CH, et al. Intensification of implementation strategies: developing a model of foundational and enhanced implementation approaches to support national adoption and scale-up. Gerontologist. 2023;63(3):604–13.

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(1):63–74.

Ritchie MJ DK, Miller CJ, Smith JL, Oliver KA, Kim B, Connolly, SL, Woodward E, Ochoa-Olmos T, Day S, Lindsay JA, Kirchner JE. Using implementation facilitation to improve healthcare (Version 3). Veterans Health Administration, Behavioral Health Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) 2020. Available at: https://www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/Facilitation-Manual.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Frost MC, Ioannou GN, Tsui JI, Edelman EJ, Weiner BJ, Fletcher OV, et al. Practice facilitation to implement alcohol-related care in Veterans Health Administration liver clinics: a study protocol. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):68.

Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, Fortney JC. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):904–12.

Siantz E, Redline B, Henwood B. Practice facilitation in integrated behavioral health and primary care settings: a scoping review. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2021;48(1):133–55.

Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):58.

Shea CM, Jacobs SR, Esserman DA, Bruce K, Weiner BJ. Organizational readiness for implementing change: a psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implement Sci. 2014;9:7.

Lee A, Vargo J, Seville E. Developing a tool to measure and compare organizations’ resilience. Nat Hazard Rev. 2013;14:29–41.

Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA, Farahnak LR. Assessing the organizational context for EBP implementation: the development and validity testing of the Implementation Climate Scale (ICS). Implement Sci. 2014;9:157.

Mancini JA, Marek LI. Sustaining community-based programs for families: conceptualization and measurement. Fam Relat. 2004;53(4):339–47.

VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI): U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2008 [VA HSR RES 13–457. Available at: https://vincicentral.vinci.med.va.gov/. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

McCullagh P. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 1989.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10:109.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117.

Leatherman S, Berwick D, Iles D, Lewin LS, Davidoff F, Nolan T, et al. The business case for quality: case studies and an analysis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(2):17–30.

Smith SN, Almirall D, Choi SY, Koschmann E, Rusch A, Bilek E, et al. Primary aim results of a clustered SMART for developing a school-level, adaptive implementation strategy to support CBT delivery at high schools in Michigan. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):42.

Eisman AB, Hutton DW, Prosser LA, Smith SN, Kilbourne AM. Cost-effectiveness of the Adaptive Implementation of Effective Programs Trial (ADEPT): approaches to adopting implementation strategies. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):109.

Kilbourne AM, Almirall D, Goodrich DE, Lai Z, Abraham KM, Nord KM, et al. Enhancing outreach for persons with serious mental illness: 12-month results from a cluster randomized trial of an adaptive implementation strategy. Implement Sci. 2014;9:163.

Eisman AB, Kilbourne AM, Dopp AR, Saldana L, Eisenberg D. Economic evaluation in implementation science: making the business case for implementation strategies. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283:112433.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation at the Durham VA Health Care System (CLIN 13-410). The authors would like to thank our clinical partners from VA project offices that provide input on project planning and site recruitment. We are also incredibly grateful for the support of the Durham VAMC public affairs team and Marshall Video who captured video footage and still images of the Group PT exercises for inclusion in the patient materials, and to the Veteran volunteers who participated in the photo and video shoots. A special thanks also to the Durham clinical application specialists that developed the EHR templates to our specification so we could track patient data across multiple VA sites. This project would not have been possible without the support of and investment by so many people. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Funding

This work was funded by the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUE-20–023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KDA, CVH, SNH, LLZ, JMH, CC, HH, and VW contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. KDA, SEW, CD, LLZ, JMH, CC, HH, SNH, CVH, BGK, LMA, LAB, JAP, CS, MT, LA, NS, and VW prepared the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, approved the final version, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Durham VA Health Care System (#2334).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Webb, S., Drake, C., Coffman, C.J. et al. Group physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: protocol for a hybrid type III effectiveness-implementation trial. Implement Sci Commun 4, 125 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00502-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00502-7