Abstract

Background

Pancreatic pseudocysts are fluid collections encapsulated by a fibrous wall. They can dissect along any path of least resistance due to extravasation of enzymatic secretions into pancreatic and peripancreatic tissues. Pseudocysts extending into perirenal space are rarely encountered with paucity of data on the occurrence of secondary page kidney. We report one such rare case of pancreatic pseudocyst in the subcapsular plane of left kidney communicating with main pancreatic duct resulting in page kidney phenomenon due to compression. We discuss this case with emphasis on early identification and management of perirenal pancreatic pseudocyst, and to salvage the renal function.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old chronic alcoholic male presented with complaints of abdominal pain, generalized weakness, dyspnea and loss of appetite since 2 weeks. On admission, he was diagnosed with newly detected hypertension. Patient was subjected to ultrasound and CECT abdomen and pelvis, which suggested acute pancreatitis and perirenal pseudocyst showing patent communication with main pancreatic duct resulting in decreased renal cortical opacification. Ultrasound-guided fluid aspiration of the perirenal cyst was performed, which showed significantly elevated amylase and lipase levels with inflammatory cells, hinting at pancreatic origin. Subsequently, percutaneous drainage of the cyst was done.

Conclusions

Pancreatic pseudocysts at distant and atypical locations pose a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma to the treating physician. Accurate clinical and radiological diagnosis of perirenal pseudocysts is extremely challenging. Early drainage of perirenal pancreatic pseudocyst prevents renal damage with subsequent pancreatic duct stenting avoiding its recurrence. Hence, it is of utmost importance as a radiologist to detect this uncommon complication at the earliest and guide the clinicians for efficient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute pancreatitis is one of the most complex and clinically challenging inflammatory conditions of the abdomen with several pathological features and complications. Most common causes in adults are alcoholism and biliary tract disease (cholelithiasis) [1].

Pancreatic pseudocyst is an accumulation of enzyme rich pancreatic secretions enclosed by fibrous tissue layer. They complicate ~ 10% of cases of acute interstitial pancreatitis [2]. They can dissect along any path of least resistance resulting in their atypical locations such as pelvis, mediastinum, intrahepatic, intrasplenic, intrarenal and perirenal spaces [3, 4]. Perirenal extension of pancreatic pseudocyst is extremely rare and is usually more common on the left side due to its anatomical proximity to pancreas [5].

Page kidney phenomenon is characterized by hypertension following renin–angiotensin system activation due to long-standing compression of renal parenchyma by a perirenal collection.

We report a rare case of perirenal pancreatic pseudocyst leading to page kidney phenomenon in a setting of acute pancreatitis, with limited literature on it [6]. The aim of this case report resides in early recognition of perirenal pancreatic pseudocyst communicating with main pancreatic duct and its proper management to prevent page kidney phenomenon and recurrence.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old chronic alcoholic male patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain, generalized weakness, abdominal fullness, dyspnea on exertion and loss of appetite since 2 weeks. On clinical examination, he was afebrile and his blood pressure measured 180/70 mmHg. He was tachypneic with oxygen saturation of 88% in room air. Per abdomen physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness.

Blood investigations revealed elevated serum amylase (648 U/L) and lipase levels (527U/L). Renal function test was within normal limits (blood urea—16 mg/dl and serum creatinine—0.9 mg/dl). Random blood glucose level was elevated—157 mg/dl.

After stabilizing the patient, ultrasound abdomen was done in the emergency department which showed a large cystic collection in the left renal fossa causing compression of left kidney with thinned out renal parenchyma. Differential diagnosis of perinephric abscess and urinoma was considered on ultrasonography.

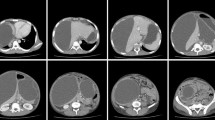

Subsequently, contrast-enhanced CT of abdomen and pelvis was performed for further evaluation of the same, using 128-slice MDCT scanner (Ingenuity core 128 v3.5.7.25001; Philips healthcare) with scanning parameters: scan direction (craniocaudally), tube voltage (120 kVp), tube current (250 mA), slice collimation (64 × 0.625 mm) and rotation time (0.5 s). Following IV contrast administration, late arterial phase and porto-venous phase were done after 35–40 s and 60–70 s, respectively. The images were reconstructed at 1 mm interval in axial, sagittal and coronal planes. The CECT depicted bulky and heterogeneously enhancing distal body and tail of pancreas with significant peripancreatic inflammation. A thick-walled peripherally enhancing collection of volume ~ 700 cc was seen in the subcapsular plane of left kidney causing its compression (Fig. 1). The collection showed communication with the main pancreatic duct (pancreatico-perirenal fistula) as shown in Fig. 2. The compressed left kidney showed thinned out renal parenchyma with relatively reduced cortical opacification when compared to opposite side (Fig. 3). Minimal ascites and bilateral mild pleural effusion was noted. The aforementioned clinical and imaging findings were suggestive of acute pancreatitis with pseudocyst formation in the left perirenal space resulting in page kidney.

Ultrasound-guided diagnostic fluid aspiration was done from the perirenal pseudocyst. On analysis, the fluid amylase and lipase were significantly elevated, i.e., 7500 IU/L and 3000 IU/L, respectively, confirming the pancreatic nature of the fluid.

The pseudocyst was drained externally via pigtail catheter. Post-drainage, repeat CT abdomen was done, which showed significant reduction in the pseudocyst volume (Fig. 4). The pancreatico-perirenal fistula was still more clearly made out as shown in Fig. 5. The patient was advised for stenting of main pancreatic duct on later date. But he was lost to follow-up thereafter. At the time of discharge, antihypertensive was started for the patient.

Discussion

As per the Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group (APCWG), diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is considered when two of the three following criteria are present: (a) epigastric pain radiating to back, (b) elevated serum amylase or lipase levels (more than three times the normal limit) and (c) imaging features suggestive of acute pancreatitis [1]. The most common causes for pancreatitis include alcoholism and biliary tract disease (cholelithiasis). The pancreatic insult results in attraction of leukocytes which release inflammatory mediators and in turn lead to disease progression and multisystem complications.

Cross-sectional imaging has improved the radiologic approach to diagnose and stage the severity of acute pancreatitis. CT is the imaging modality of choice with accurate anatomical delineation of peripancreatic tissue and fascial planes. MRI is a better imaging modality in the characterization of peripancreatic fluid collections; however, the cost and lengthy procedural duration are the major hindrances, given the condition of the patients [1].

Pancreatic pseudocyst is a collection of pancreatic secretions enclosed in fibrous tissue layer, without an epithelial lining. They usually develop four weeks after an acute episode or can be associated with chronic pancreatitis. Pseudocysts complicate ~ 10% of cases of acute interstitial pancreatitis [2]. They can develop in ectopic sites distant from pancreatic bed such as pelvis, mediastinum, intrahepatic, intrasplenic, intrarenal and perirenal spaces [3, 4]. It is essential to differentiate walled-off necrosis from pseudocyst, as the former has increased mortality and high rates of secondary infection [1, 7].

Pancreatic pseudocyst extending into perinephric space has been rarely reported, in ~ 0.9–1.25% of patients with pancreatitis [8]. Kashima et al. reported a case of pancreatic pseudocyst penetrating into left renal subcapsular region with pancreatic ductal communication [9].

Digestion of perirenal fat and renal fascia due to seepage of the autolytic enzymes from the inflamed pancreas precedes renal pseudocyst formation [8]. Left kidney is more prone to experience perirenal pseudocysts due to its close anatomic relation with pancreas, whereas on right side, duodenum acts as a barrier [5, 10]. Further, the perirenal pseudocysts may cause renal afflictions in several ways by compressing, distorting or damaging the renal tissue [11]. Rosenquist et al. have reported about two cases of pancreatic pseudocyst deforming the upper pole of left kidney [4]. It can also cause pseudoaneurysm in the kidney or urinary tract obstruction [12, 13]. Rarely, renal pseudocysts can cause compression of the renal parenchyma resulting in page kidney. Aswani et al. described about a case of acute pancreatitis presenting with page kidney secondary to compression by subcapsular extension of pancreatic pseudocyst [6]. Page kidney phenomenon refers to renal compression due to hematoma, tumor, lymphocele or urinoma causing renal hypoperfusion and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone cascade activation resulting in hypertension.

Treatment requires relief of compression and anti-hypertensives. Minimally invasive techniques such as evacuation of perinephric collection can relieve compression, whereas hypertension is usually managed using ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. However, renal pseudocysts may show a substantial overlap of radiological features. Pseudocysts wrapping around the kidney can resemble renal tumors, cysts, hematoma, lymphocele or urinoma, posing a diagnostic dilemma [14, 15]. Hence, cross-sectional imaging, especially contrast-enhanced computed tomography, provides indispensable information regarding the exact location, origin and involvement of adjacent structures.

Conclusions

Pancreatic pseudocysts have a propensity to spread through fascial planes into various anatomical compartments resulting in ectopic collections. Perirenal extension of pancreatic pseudocyst is atypical, foreknowledge of which is imperative for a reliable diagnosis. Early detection and drainage of the collection to relieve compression over the kidney is essential to avoid complications and subsequently perform pancreatic duct stenting to prevent recurrence. Hence, when such a radiographic presentation is demonstrated, the radiologist plays a pivotal role in diagnosing the same.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy of the study participant.

Abbreviations

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- APCWG:

-

Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

References

Cunha EF, Rocha MDS, Pereira FP, Blasbalg R, Baroni RH (2014) Walled-off pancreatic necrosis and other current concepts in the radiological assessment of acute pancreatitis. Radiol Bras 47(3):165–175. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2012.1565

Foster BR, Jensen KK, Bakis G, Shaaban AM, Coakley FV (2016) Revised atlanta classification for acute pancreatitis: a pictorial essay. Radiographics 36(3):675–87. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150097. Erratum in: Radiographics 39(3):912 (2019)

Munkelwitz R, Krasnokutsky S, Mohan E, Lie J, Shah SM, Khan SA (1997) Unusual presentation of a pancreatic pseudocyst. A case report and review of literature. Int J Pancreatol 21(1):91–94

Rosenquist CJ (1973) Pseudocyst of the pancreas: unusual radiographic presentations. Clin Radiol 24(2):192–194

Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Nanda M, Chandail VS, Masoodi I, Kang M, Kalra N, Sinha SK, Nagi B, Singh K (2010) Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts at atypical locations. Surg Endosc 24(5):1085–1091

Aswani Y, Anandpara KM, Hira P (2015) Page kidney due to a renal pseudocyst in a setting of pancreatitis. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-207436

Baron TH, Morgan DE, Vickers SM, Lazenby AJ (1999) Organized pancreatic necrosis: endoscopic, radiologic, and pathologic features of a distinct clinical entity. Pancreas 19(1):105–108

Feldberg MA, Hendriks MJ, van Waes PF, Sung KJ (1987) Pancreatic lesions and transfascialperirenal spread: computed tomographic demonstration. Gastrointest Radiol 12(1):121–127

Kashima S, Inoue T, Chiba M, Komine N, Ito R, Numakura K, Tsuruta H, Saito M, Akihama S, Narita S, Tsuchiya N (2014) Renal subcapsular fluid collection caused by penetration of a pancreatic pseudocyst. Urology 84(5):e23–e24

Thandassery RB, Mothilal SK, Singh SK, Khaliq A, Kumar L, Kochhar R, Singh K, Kochhar R (2011) Chronic calcific pancreatitis presenting as an isolated left perinephric abscess: a case report and review of the literature. J Pancreas 12(5):485–488

Farman J, Kutcher R, Dallemand S, Lane FC, Becker JA (1978) Unusual pelvic complications of a pancreatic pseudocyst. Gastrointest Radiol 3(1):43–45

Abrol N, Seth A, Sharma S (2012) Pseudoaneurysm kidney: a rare complication of pseudopancreatic cyst. Urology (Ridgewood, NJ) 79(1):111–112

Matsumoto F, Tohda A, Shimada K, Kubota A (2005) Pancreatic pseudocyst arising from ectopic pancreas and isolated intestinal duplication in mesocolon caused hydronephrosis in a girl with horseshoe kidney. J Pediatr Surg 40(7):e5-7

Naftel W, Ravera J, Herr HW (1975) Pseudocyst of pancreas simulating a renal neoplasm. Urology 5(3):417–419

Kiviat MD, Miller EV, Ansell JS (1971) Pseudocysts of the pancreas presenting as renal mass lesions. Br J Urol 43(3):257–262

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank our esteemed institution JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore, for encouraging and providing support in all our endeavors. I also take this opportunity to express my gratitude to all the faculty, postgraduates, technical and supporting staff of Department of Radiology.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH contributed to study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data and supervision of the project. TKC was involved in study conception and design and drafted the manuscript preparation. BG was involved in study conception and design and drafted the manuscript preparation. DVK drafted the manuscript preparation and contributed to supervision of the project. SRP drafted the manuscript preparation and was involved in supervision of the project. SRB drafted the manuscript preparation. All authors discussed the case report and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was waived off by the Ethics committee of JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru, India, for single patient case report, and written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient. Only anonymized data and images were used.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication, and only anonymized data and images were used.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hiremath, R., Kuttancheri, T., Gurumurthy, B. et al. A new page in the literature of pancreatic pseudocyst: case report on perirenal pseudocyst presenting as page kidney. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 53, 240 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00925-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00925-7

—pancreatic tail,

—pancreatic tail,

—subcapsular collection

—subcapsular collection