Abstract

Background

Pneumopericardium is a rare complication in patients with bacterial necrotizing pneumonia and proven to be lethal with a high incidence of mortality due to cardiopulmonary failure.

Case presentation

This is a rare case of broncho-pericardial fistula in a 21 year old, who was a known case of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia status post-chemotherapy, presented with relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. He was evaluated for febrile neutropenia. Further investigation showed features of necrotizing pneumonia and follow-up chest X-ray during the hospital stay showed evidence of pneumopericardium. To localize the cause, computed tomography chest was performed, further confirming the etiology of bronchopericardial fistula.

Conclusions

Our case illustrates broncho-pericardial fistula as a rare complication of necrotizing pneumonia and the utility of multimodality imaging in its diagnosis and determination of tension pneumopericardium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pneumopericardium is the presence of air within the pericardial space. The most common etiologies include iatrogenic factors, positive pressure mechanical ventilation, and less commonly pericardial infections with gas producing organisms [1]. It is a rare complication in cases with bacterial necrotizing pneumonia and proven to be lethal, further leading to cardiac tamponade and hemodynamic instability [2]. The overall mortality of pneumopericardium has been estimated as 57% [3].

Case presentation

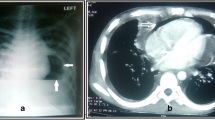

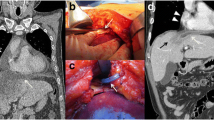

A 21-year-old male, known case of T-cell ALL status post-chemotherapy, presented with relapse of ALL. His presenting complaints were breathlessness, fever, burning micturition, and he was further evaluated for febrile neutropenia. Laboratory workup showed pancytopenia with a total leukocyte count (TLC) of 300. The patient was transferred to intensive care on day 8 of his admission in view of severe breathlessness. HRCT chest on day 11 of admission showed evidence of multifocal consolidations in bilateral lung parenchyma, predominantly involving the lower lobes (Fig. 1). The bronchoalveolar lavage came out to be acinetobacter positive. HRCT chest on day 17 of admission showed interval appearance of cavitatory changes, suggestive of necrotizing pneumonia (Fig. 2). The patient developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and deteriorated further. The patient was intubated and kept on positive pressure ventilation. On day 23 of admission, chest X-ray showed evidence of pneumopericardium (Fig. 3). Pericardiocentesis was performed. Air leak from the pericardial catheter was synchronous with mechanical ventilation, which strongly suggested a pericardial communication with the airway. Follow-up HRCT chest was done to look for the underlying etiology, which showed interval increase in cavitatory consolidations and interval appearance of moderate to significant pneumopericardium. A subsegmental area of air space consolidation was seen encasing the medial segmental bronchus of the right middle lobe with eccentric cavitation, showing trans-pericardial contiguity with resultant broncho-pericardial fistula. Significant compression over cardiac chambers, predominantly on right atrium and right ventricle was also seen. The pericardial drain was seen in situ in posterior pericardial cavity, as well as bilateral pleural effusions (Fig. 4). The patient unfortunately succumbed to cardiopulmonary arrest the very next day, despite aggressive management.

Non-contrast computed tomography Chest on day 24 of admission shows subsegmental area of consolidation encasing medial segmental bronchus of the right middle lobe, with eccentric cavitation showing transpericardial contiguity. Significant pneumopericardium with cardiac air tamponade is also noted. Note is made of bilateral pleural effusions. Pericardial catheter is seen lying in posterior pericardial cavity (blue arrow). Note the presence of broncho-pericardial fistula (white arrow)

Discussion

Pneumopericardium should always raise a suspicion for broncho-pericardial fistula, tracheo-pericardial or gastro-pericardial fistula. The causative factors include blunt trauma, penetration trauma, carcinoma, or iatrogenic [4]. Other less common causes are bacterial necrotizing pneumonia, HIV, hepatitis, and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. In this case, due to the immunocompromised status of the patient, he developed necrotizing pneumonia. Acinetobacter baumannii is a rare cause of necrotizing pneumonia which is highly virulent and shows antimicrobial resistance compared with other organisms [5]. Complications of necrotizing pneumonia include parapneumonic effusions, pleural empyema, and bronchopleural fistula. In our case, the patient developed the rare complication of secondary broncho-pericardial fistula formation from cavitatory changes alongside the pericardium and resultant tension pneumopericardium. Mass effect on the heart was seen, causing impairment of right ventricular filling, resulting in pericardial tamponade with increase and equalization of intracardiac pressures, pulsus paradoxus, arterial hypotension, and resultant cardiogenic shock [6]. Pneumopericardium often does not require any specific treatment. However, in view of tension pneumopericardium, traditional therapy such as tube decompression was employed in our case.

Conclusions

Our case illustrates broncho-pericardial fistula as a rare complication of necrotizing pneumonia and the utility of multimodality imaging for the diagnosis of bronchopericardial fistula and tension pneumopericardium.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used in this study in the form of images were collected after getting proper permission from the authorized person.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution computed tomography

- ALL:

-

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- TLC:

-

Total leukocyte count

References

Bennett JA, Haramati LB (2000) CT of bronchopericardial fistula: an unusual complication of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in HIV infection. Am J Roentgenol 175(3):819–820

Arab AA, Kattan MA, Alyafi WA, Alhashemi JA (2011) Broncho-pleuropericardial fistula complicating staphylococcal sepsis. Saudi J Anaesth 5(4):434

Shelke AB, Kawade R, Gandhi S (2017) A case of bronchopericardial fistula with tension pneumopericardium closed successfully by transpericardial intervention: a novel procedure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 90(7):1117–1120

Owens CM, Graham TR, Wood AJ, Newland AC (1990) Bronchopericardial fistula and pneumopericardium complicating invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Lab Haematol 12(3):351–354

Tsai YF, Ku YH (2012) Necrotizing pneumonia: a rare complication of pneumonia requiring special consideration. Curr Opin Pulm Med 18(3):246–252

Maurer ER, Mendez FL Jr, Finklestein M, Lewis R (1958) Cardiovascular dynamics in pneumopericardium and hydropericardium. Angiology 9(3):176–179

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed well. PB wrote and edited pictures in this case report. VA and JK analyzed and interpreted images along with all the corrections. SS reviewed it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent for the patient information and images to be published was obtained from the next of kin of the patient. Ethics committee approval was obtained from “Ethics committee of review board of Christian Medical College and hospital, Ludhiana”.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the next of kin of patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

There were no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bharti, P., Agarwal, V., Kuruvilla, J. et al. An unusual case of bronchopericardial fistula secondary to necrotizing pneumonia. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 53, 159 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00852-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00852-7