Abstract

Background

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a complex and uncommon disorder with as its main feature a patchy or mosaic postnatal overgrowth. A high clinical and radiological variability characterizes it.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 2-year-old boy presenting with lipomas and diagnosed as PS in front of general criteria (sporadic occurrence, progressive course, and mosaic distribution of lesions) and specific criteria (linear epidermal nevus in the chest and asymmetric and overgrowth in the upper limbs) of Biesecker. The course of the disease was marked by a huge overgrowth of arms despite several surgeries. By the age of 10 years, a painful swelling of the right forearm revealed a venous thrombosis on a venous malformation.

Conclusions

This case report highlights the variability of clinical findings in PS. It also emphasizes the contribution of routine imaging tools for the diagnosis and the follow-up of this rare disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a rare congenital syndrome that can be categorized as a hamartomatous disorder. This syndrome is characterized by a great clinical variability due to a bony and soft tissue overgrowth [1]. Diagnostic criteria for PS were controversial making difficult its diagnosis. This complex disorder is thought to affect fewer than 200 individuals in the developed world [2].

The radiologist interferes at so many levels, using practically different imaging tools in accordance with the highly variable manifestations of this disorder. The diagnosis, the follow-up, the detection of complications, and even the prenatal screening depend heavily on imaging findings [3].

We report the case of a boy diagnosed as having a PS, and we review the role of the radiologist in the multidisciplinary management of this rare pathology.

Case presentation

Our patient is the second living child of unrelated parents. He had one older healthy sister. His mother was 33 years old, and his father was 40 years old at the time of his birth. There was no significant family medical history. His examination was unremarkable at birth. An accelerated and asymmetric growth of the upper limbs from the age of 9 months was noted by parents. No diagnosis was made at this age. At 2 years and half, he was investigated for subcutaneous masses in the upper right limb. The diagnosis of lipomas was retained on biopsy and the child was referred to the pediatrics department.

The diagnosis of PS was taken into consideration based on Biesecker criteria 2006 (Table 1) [4]. These criteria were the most recent at the time of the first patient’s consultation in 2008.

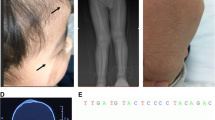

The diagnosis of PS was retained on the proband based on the presence of all general criteria (sporadic occurrence, progressive course of the disease, mosaic distribution of lesions) and two specific criteria from category B (linear epidermal nevus in the upper chest, asymmetric and disproportionate overgrowth of upper limbs). Besides, he had macrodactyly and syndactyly in the left hand. Genetic screening was not done in our patient because it was not affordable.

The boy was referred to the orthopedic department. He was operated on three times to help stop the overgrowing of arms and fingers bones. The last surgery was made at 6 years old. He was then lost to follow-up due to the family’s financial difficulties. He was readmitted to the pediatrics department at 10 years old for an inflammatory swelling in the right forearm. We noticed an important overgrowth of his arms and fingers (Fig. 1), a scoliosis, an overgrowth of adenoids, and a hepatomegaly (liver span at 11 cm). His psychomotor development was normal.

X-ray assessment revealed multiple skeletal anomalies (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

The abdominal ultrasound exam was normal except for hepatomegaly.

Right forearm’s ultrasound exam coupled with Doppler showed “low-flow” tortuous “polycystic and communicating lesions with no apparent flow-signal at rest (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). If repeatedly compressed by the HR-US probe, the lesions appeared soft and well compressible and showed a typical color-shift signal within. The above-mentioned features were related to venous malformations. A dilated vein was filled with echogenic material and was not compressible corresponding to a thrombotic vein (venous malformation affected by thrombophlebitis) (Fig. 6).

The patient was put on low molecular weight heparin with favorable outcome.

The subsequent course was marked by several episodes of thrombosis of the superficial veins in upper limbs with favorable outcome under medical treatment. The patient has never had a pulmonary embolism with a follow-up of 8 years (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Mosaic overgrowth syndromes are a group of uncommon diseases presenting as asymmetric, segmental, and often progressive overgrowth involving any tissue type. Clinical presentations are discordant ranging from isolated malformations to life-threatening conditions. These syndromes result from mosaic somatic, post-zygotic mutations in genes involved in cell growth and proliferation. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is mainly involved. Proteus syndrome is an AKT1-related syndrome [5].

PS was rarely reported in Tunisian children. This syndrome remains little-known in our country, and our case report emphasizes an illustrative phenotype. In addition, our case is not limited to the clinical presentation but specifies the radiological particularities, a key point in the diagnosis and management of this syndrome. Our main limitation is the absence of a genetic study, but this does not hinder the diagnosis.

Proteus syndrome (OMIM # 176,920) is a rare overgrowth condition. It was first described in 1979, by Hayden and Cohen, in two patients [1]. It is a highly polymorph and complex disease that associates overgrowth of multiple tissues and malformations. No two patients with PS are exactly alike. Most of the affected persons appear healthy at birth, but typically during the child’s first year, some parts of their bodies begin to grow faster and larger than they should [6].

Diagnosis of PS is challenging and evolving. Its intrinsic variability made it necessary to establish diagnostic criteria in 1999 [7]. These criteria were revised in 2006 [4].

A mosaic activating AKT1 mutation (c.49G > A, p.Glu17Lys) was identified in PS. This was first published in 2011 [8].

Biesecker et al. in a study published in 2019 presented a new approach to diagnose PS. Most of the diagnosis criteria were used unmodified (Biesecker, 2006; Biesecker et al., 1999). However, other factors were added. It was about pulmonary embolism, vein thrombosis, and other tumor types testicular cystadenomas/adenocarcinomas and meningiomas. Cardiac septal lipoma was also added in the category “lipomas/dysregulated adipose. Finally, the authors added two negative criteria: substantial prenatal extracranial overgrowth and ballooning overgrowth since uncommon in PS. Subsequently, they set a boundary at ≥ 15 points to consider an individual to have a clinical diagnosis of PS in the absence of an AKT1 variant. Individuals with a score of ≥ 10 points and a pathogenic mosaic variant in AKT1 were considered as having AKT1-related PS. In the case of a score of 2 to 9 points associated with pathogenic mosaic variant in AKT1, the diagnosis of AKT1-related overgrowth spectrum was retained [9]. The diagnosis of PS was retained in our patient in 2008 based on the Biesecker et al. 2006 criteria [4]. This diagnosis was reassessed according to Biesecker et al. 2019 criteria [9]. According to this new approach, our patient has a score of 16 (all general criteria; asymmetric, disproportionate overgrowth of limbs, and scoliosis (5 points); overgrowth of adenoids and liver (5 points); lipomas (2 points); linear epidermal nevus (2 points); and venous malformations (2 points)). Screening for AKT1 mutation has not been done due to financial considerations. Although we have no genetic confirmation for PS, this diagnosis was retained since we have a score of 16. Other syndromes partially superimposable to PS such as CLOVES syndrome, neurofibromatosis 1, or PTEN hamartoma tumor [10] were excluded based on clinical, histological, and radiological presentation in our patient.

PS is also characterized by orthopedic complications which are one of the most challenging medical problems. Various cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions (lipomas, vascular malformations and several types of nevi) are also evocative. Most commonly vascular malformations are of capillary type. However, some patients have venous malformations. Arterial vascular malformations are uncommon in PS. Intracranial arteriovenous malformations were described in one case [6, 7].

The typical ultrasound aspect of venous malformation is a polycystic, sponge-like, pseudo-tumorous lesion positioned subcutaneously and composed of complex and communicating venous vessels [2, 11]. The separating walls may be of variable thickness which renders the B-mode appearance very inhomogeneous. Thrombotic precipitates filling the vascular lumen are sometimes found. They are due to vascular wall abnormalities and to very low blood flow velocities. Indeed, patients with PS are at risk to get deep vein thrombosis, which can lead to pulmonary embolism [12]. Males appear to be at greater risk for thrombosis than females. It is important for doctors caring for people with PS to be aware of this risk [13]. Our patient presented a thrombosis 8 years after initial diagnosis.

Accurate management of patients with PS can be very well assessed through several imaging modalities.

Multiple imaging techniques are useful in the evaluation of PS. A radiograph skeletal survey is needed to identify bone anomalies. CT of the chest is helpful in the evaluation for pulmonary embolism. Abdominal and pelvic CT or MRI can be used to evaluate visceromegaly and to search for asymptomatic but potentially aggressive lipomatosis. Central nervous system MRI is needed to identify brain anomalies in patients with neurologic symptoms [2, 11].

Ultrasonography is very useful to characterize the subcutaneous lesions. Besides, it offers, with the use of the Doppler, the possibility to assess vascular malformations and to easily diagnose venous thrombosis. The latter occurs at an increased frequency in PS and exposed to pulmonary embolism major cause of premature death.

The 2004 guidelines indicate for patient assessment [2]:

-

–Serial clinical photography

-

–Initial skeletal survey with targeted follow-up radiographs

-

–MR imaging of clinically affected areas and in asymptomatic patient, an MRI of chest and abdomen

-

–Dermatologic and orthopedic consultations as long with a pediatric management

Radiologic findings are multiple. Table 2 summarizes the most common ones in patient with PS [2]. The current treatment of PS is mainly symptomatic and aims to decrease disability and promote a better quality of life. AKT1 inhibitor miransertib seems to be an interesting molecule to investigate [13].

Conclusion

Proteus syndrome is a rare pathology involving a variety of organs and thus implicating different physicians. The high variability of clinical presentation makes the diagnosis challenging. The management depends on the results of the first assessment based on physical examination and imaging investigation. Being aware of the radiological specificities of PS is essential for diagnosis and follow-up. To increase the accuracy of diagnosis, the use of the most recent published diagnostic is recommended. However, radiological assessment is particularly useful in low-income countries where genetic testing is not usually affordable as in our patients.

Availability of data and materials

Available under reasonable request.

References

Cohen MM Jr (2005) Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 137C(1):38–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.30063

Jamis-Dow CA, Turner J, Biesecker LG, Choyke PL (2004) Radiologic manifestations of Proteus syndrome. Radiographics 24(4):1051–1068. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.244035726

Kaduthodil MJ, Prasad DS, Lowe AS, Punekar AS, Yeung S, Kay CL (2012) Imaging manifestations in Proteus syndrome: an unusual multisystem developmental disorder. Br J Radiol 85(1017):e793–e799. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/92343528

Biesecker L (2006) The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet 14(11):1151–1157. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201638

Morin G, Canaud G (2021) Treatment strategies for mosaic overgrowth syndromes of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. Br Med Bull 140(1):36–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldab023

Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Dillman JR, Platt JF, Willatt JM, Heiken JP (2008) Vascular malformation and hemangiomatosis syndromes: spectrum of imaging manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 190(5):1291–1299. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.07.2779

Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB et al (1999) Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet 84(5):389–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990611)84:5%3c389::aid-ajmg1%3e3.0.co;2-o

Lindhurst MJ, Sapp JC, Teer JK et al (2011) A mosaic activating mutation in AKT1 associated with the Proteus syndrome. N Engl J Med 365(7):611–619. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1104017

Sapp JC, Buser A, Burton-Akright J, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Biesecker LG (2019) A dyadic genotype-phenotype approach to diagnostic criteria for Proteus syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 181(4):565–570. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31744

Arredondo Montero J, Bronte Anaut M, López-Gutiérrez JC (2022) Proteus syndrome: case report with anatomopathological correlation. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 41(5):861–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/15513815.2021.1989097

Turner JT, Cohen MM Jr, Biesecker LG (2004) Reassessment of the Proteus syndrome literature: application of diagnostic criteria to published cases. Am J Med Genet A 130A(2):111–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.30327

Asilian A, Kamali AS, Riahi NT, Adibi N, Mokhtari F. Proteus syndrome with arteriovenous malformation. Adv Biomed Res. 2017;6:27. Published 2017 Mar 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9175.201684

Zeng X, Wen X, Liang X, Wang L, Xu L. A case report of Proteus syndrome (PS). BMC Med Genet. 2020;21(1):15. Published 2020 Jan 21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-0949-x

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient and the family for their support of this submission including the written informed consent for publication.

Funding

The authors declare no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Khelifi Azza: collected data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript.

Barakizou Hager: revised the initial manuscript, made further literature review, and edited the final manuscript.

Ferjani Maryem: revised the manuscript.

Gargah Tahar: revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final content of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hager, B., Azza, K., Maryem, F. et al. Proteus syndrome: clinical and radiological findings through a new case report. Egypt Pediatric Association Gaz 72, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-024-00266-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-024-00266-2