Abstract

Background

Although some investigators have confirmed the association between H. pylori and chronic ITP in adults, studies in pediatric patients are still few and have produced conflicting results. The study was carried out to detect the prevalence of H. pylori among chronic ITP children and to investigate the impact of treatment of H. pylori infection on platelet count response.

Results

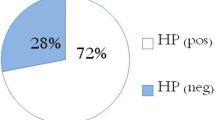

The prevalence of H. pylori in chronic ITP children was 63%. The platelet count was statistically significantly higher among H. pylori stool antigen (HpSA)-negative children. A significant difference was reported in which platelet count increased from 70.55 ± 4.788 million/μL before H. pylori eradication therapy to 110.78 ± 15.128 million/μL after therapy.

Conclusion

We concluded that H. pylori eradication therapy was effective in increasing platelet count in H. pylori-positive chronic ITP patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is mostly thought to be an autoimmune disorder in which several pathologic immune mechanisms participate in accelerated destruction as well as inhibition of production of platelets. The end result is thrombocytopenia which is defined as platelets less than 100 million/μL that leads to clinical symptoms of bleeding [1]. ITP is classified as an acute ITP where the duration of illness is less than 3 months, persistent ITP with a 3–12-month duration, and chronic ITP with a duration of ≥ 12 months [2, 3].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral gram-negative pathogenic bacterium found in the stomach of humans in all parts of the world with high prevalence in developing countries. It is the causal agent for several gastric diseases including chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric lymphoma. Furthermore, H. pylori infection is the single most important risk factor for gastric cancer [4].

A pathophysiologic association between ITP and H. pylori was initially suggested by Gasbarrini et al. in 1998 [5]. Although the pathogenesis of H. pylori-associated ITP is still not confirmed, several studies have mentioned that cytotoxin-associated gene A (cagA), a virulence factor of H. pylori, elicits the production of anti-cagA antibodies that cross react with platelet surface antigens resulting in thrombocytopenia. However, there is a debate about whether the eradication of H. pylori in chronic ITP results in an improvement in platelet count or not [6,7,8]. This study was performed to investigate the impact of treatment of H. pylori infection on platelet count response in chronic ITP children.

Methods

Study design and setting

The study was designed to conduct into two consequential phases as detailed hereafter:

-

Phase I: a cross-sectional design was carried out in the hematology clinic and inpatient of the pediatrics department during the period from January to December 2019 to explore prevalence of H. pylori among chronic ITP children.

-

Phase II: interventional design among chronic ITP children who were reported positively for H. pylori to investigate the impact of treatment of H. pylori infection on platelet count response.

Study population

The study was conducted on one hundred children, through their regular visits to the hematology clinic for follow-up. Target children aged 02–18 years old and diagnosed with chronic ITP through convenient sampling.

Inclusion criteria

Based on the criteria of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) [9], children were diagnosed with ITP when the initial platelet count is < 100000 to avoid the confusing effect of the incident ITP therapies. Eligible children are those who have platelet count above 20000 and below 100000.

Exclusion criteria

Children with other causes of thrombocytopenia such as HCV, HBV, or HIV, drugs, lymphoproliferative disorders, other auto-immune disorders, and children with active life-threating bleeding at the time of recruitment were excluded.

Sampling

The number of participants was estimated using the Epi-Info version 7 StatCalc designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO). We exceeded the least required sample size to enhance statistical power and avoid unpredicted low response rates.

Study procedures

The authors filled out a comprehensive questionnaire for each patient, involving detailed history and physical examination. We collected a venous blood sample from each patient for laboratory investigation, including CBC with a direct platelet count. Finally, stool samples were collected in clean containers used for the detection of H. pylori Ag; colored chromatographic immunoassay for the qualitative detection of Helicobacter pylori antigen using CerTest H. pylori detection kit (CERTEST BIOTEC, Spain). It is a strip consisting of a nitrocellulose membrane pre-coated with mouse monoclonal antibodies against H. pylori on the test line (T) and with a rabbit polyclonal antibodies against a specific protein on the control line (C).

Standard H. pylori eradication therapy

Treatment of H. pylori infection in the form of amoxicillin 50 mg/kg day, clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks, and proton pump inhibitor 1 mg/kg/day was given to all cases for 1 month.

Reevaluation of their H. pylori status and platelet count was done 6 months after stopping the treatment to assess the efficacy of treatment of Helicobacter infection (whether the patient was cured of H. pylori infection or not) and to investigate the effect of H. pylori eradication on the patient’s platelet count.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine. The authors explained the aim and procedures of the study for parents and assured the confidentiality of the data collected, as well as that of the laboratory tests. We got informed consent from parents of children prior to the recruitment.

Statistical analysis

We applied statistical analysis using SPSS version 15 (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as frequencies, percentages, and mean ± standard deviation when appropriate. For numerical variables, the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used for independent samples and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired (matched) samples. For categorical data, the chi-square (χ2) test was performed. In case of expected frequency of less than 5, the exact test was applied instead. Spearman rank correlation equation was used for the correlation between various variables. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

One hundred children were enrolled in the study; 46 (46%) were males, and 54 (54%) were females. H. pylori-positive cases were found to have a mean age of 7.62 ± 3.6 years, while the negative ones had a mean age of 6.35 ± 3.1 years. The platelet count was statistically significantly higher among H. pylori stool antigen (HpSA)-negative children as depicted in Table 1.

A significant difference was reported in platelet count before H. pylori eradication 70.6 ± 14.8million/μL while after eradication therapy platelets count significantly increased to 110.8 ± 15.1 million/μL as shown in Table 2.

We followed up all the study patients for 6 months. We found a significant sustained response in H. pylori eradicated cITP cases. The reevaluation of HpSA-positive cases showed that 35 patients (55.56%) had complete recovery (CR), 21 patients (33.33%) had partial recovery (PR), and 7 cases (11.11%) reported no response (NR) as shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The role of treatment of H. pylori infection in ITP is controversial; in our research, we investigated the influence of treatment of H. pylori infection in children with ITP.

ITP is believed to be an organ-specific autoimmune disorder. It is mediated by anti-platelet Abs that bind to host platelets and megakaryocytes, speeding up platelet destruction by the reticuloendothelial system [10]. The auto-antibodies primarily target platelet surface glycoproteins such as GP Ib and GP IIb/IIIa. Although the provoking factors for ITP are obscure, bacterial or viral infections are noted to be related with the development of ITP, illustrating that infectious agents may perform a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of a particular subset of ITP [11].

In chronic ITP, platelet counts may range between 1 million/μL and 100 million/μL. The threshold for pharmacologic treatment depends on multiple factors, including ongoing bleeding, risk factors for bleeding (e.g., sports or an active lifestyle), anxiety, fatigue, access to medical care, concomitant conditions, and medications [12]. Some studies have confirmed the association between H. pylori and chronic ITP in adults, while studies in pediatric cases are few and have presented conflicting results [13].

In the present study, platelet count was statistically significantly higher among H. pylori stool antigen (HpSA)-negative children (85.7 [million/μL] ± 7.2) than H. pylori stool antigen (HpSA)-positive children (70.6 [million/μL] ± 4.8). This may be explained by the auto-Abs primarily target platelet surface glycoproteins such as GP IIb/IIIa and GP Ib [11].

In our study, there was a significant rise in the mean platelet count in (million/μL) in H. pylori-positive children from 70.6 ± 4.8 to 110.8 ± 15.1 after H. pylori eradication therapy [P value < 0.001]. Stasi et al. and Noonavath et al. found similar results.

This may be explained by that the CagA antigen of H. pylori might account for the cross-mimicry between H. pylori and platelet glycoproteins. On the contrary, it has been proved that platelet-associated IgG from 12 out of the 18 ITP patients detected H. pylori CagA protein and that cross-reactive Ab levels were reduced after H. pylori eradication in patients showed complete platelet recovery [6].

There is a great difference in prevalence of H. pylori infection in chronic ITP (cITP) patients between studies. Our study revealed H. pylori infection in 63% of chronic ITP patients. A previous research, operated in Italy, showed H. pylori prevalence estimate of 50% in chronic ITP patients. Other studies in Japan showed that 75% of the cITP cases were identified to have H. pylori infection. However, surveys conducted in French and North American Caucasian cITP patients revealed a low prevalence rate [14]. Meanwhile, a prevalence rate of 50–80% has been pronounced in studies from Japan, Iran, and Korea [15]. It has already been illustrated that after HPET treatment, the cITP of shorter duration responds better compared to the long-standing ones [16, 17].

Regarding platelets recovery after H. pylori eradication therapy, our study revealed that sixty-three children were H. pylori stool antigens (HpSA) positive; thirty-five of them (55.56%) had a complete response after H. pylori eradication therapy while twenty-one patients (33.33%) had a partial response and 7 patients (11.11%) had no response. These results were statistically significant (P = 0.001) and consistent with results of other researches [7, 12]. In contrast to our study, Ahn et al. [18] reported a poor response to H. pylori eradication treatment in patients suffering chronic ITP in Western countries. Another study reported that H. pylori eradication therapy had no or poor effects on the platelet counts in the patients with cITP [19–22].

Conclusion

Accordingly, we conclude that H. pylori eradication therapy was effective in raising the platelet count in H. pylori-positive chronic ITP cases. Further researches are recommended to determine other probable causative factors concerned in the platelet recovery and to understand the process regulating the response to eradication therapy.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ITP:

-

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura

- HPET:

-

Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy

- HpSA:

-

Helicobacter pylori surface antigen

- CR:

-

Complete recovery

- PR:

-

Partial recovery

- NR:

-

No response

- CagA:

-

Cytotoxin-associated gene A

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

References

Sun RJ, Shan NN (2019) Megakaryocytic dysfunction in immune thrombocytopenia is linked to autophagy. Cancer Cell Int 19:59

Kühne T, Berchtold W et al (2011) Newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia in children and adults: a comparative prospective observational registry of the intercontinental cooperative immune thrombocytopenia study group. Haematologica 96:1831–1837

Provan D, Stasi R et al (2010) International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 115:168–186

Bravo D, Hoare A et al (2018) Helicobacter pylori in human health and disease: mechanisms for local gastric and systemic effects. World J Gastroenterol 24:3071

Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F et al (1998) Regression of autoimmune thrombocytopenia after eradication of helicobacter pylori. Lancet 352:878

Takahashi T, Yujiri T et al (2004) Molecular mimicry by helicobacter pylori CagA protein may be involved in the pathogenesis of H. pylori -associated chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol 124:91–96

Kodama M, Kitadai Y et al (2007) Immune response to CagA protein is associated with improved platelet count after helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Helicobacter 12:36–42

Zain MA, Zafar F et al (2019) Helicobacter pylori: an underrated cause of immune thrombocytopenic purpura. A comprehensive review. Cureus 11(9):e5551

Cines DB, Bussel JB et al (2009) The ITP syndrome: pathogenic and clinical diversity. Blood J Am Soc Hematol 113:6511–6521

Stasi R (2012) Immune thrombocytopenia: pathophysiologic and clinical update. Semin Thromb HemostThieme Medical Publishers 16:122

Stasi R, Willis F et al (2009) Infectious causes of chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Hematology/Oncology Clinics 23:1275–1297

Klaassen RJ, Mathias SD et al (2012) Pilot study of the effect of romiplostim on child health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and parental burden in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Pediatr Blood Cancer 58:395–398

Despotovic JM, Bussel JB (2019) Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). platelets. Elsevier, USA, pp 707–724

Stasi R, Provan D (2008) Helicobacter pylori and chronic ITP. ASH Education Program Book 2008:206–211

Yim JY, Kim N et al (2007) Seroprevalence of helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter 12:333–340

Noonavath RN, Lakshmi CP et al (2014) Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 20:6918

Stasi R, Sarpatwari A et al (2009) Effects of eradication of helicobacter pylori infection in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review. Blood J Am Soc Hematol 113:1231–1240

Ahn ER, Tiede MP et al (2006) Platelet activation in helicobacter pylori associated idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: eradication reduces platelet activation but seldom improves platelet counts. Acta Haematol 116:19–24

Stasi R, Rossi Z et al (2005) Helicobacter pylori eradication in the management of patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med 118:414–419

Bisogno G, Errigo G et al (2008) The role of helicobacter pylori in children with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30:53–57

Moghimi M (2019) Helicobacter pylori eradication in adult patients with acute idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). J Adv Med Biomed Res 11:88

Kim BJ, Kim HS et al (2018) Helicobacter pylori eradication in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract 16:18

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients’ families for their receptivity and the authorized managers of selected schools for logistical support.

Funding

Not applicable (N/A)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMH interpreted the patients data and contributed to the writing and revising of the manuscript. AGA collected the samples and drafted the draft. NMK performed the immunological analysis. SAS performed the statistical data analysis. EMF performed the immunological analysis and drafted the manuscript. AA designed the experiment and contributed to the interpretation of patients’ data and in writing and revising of the manuscript. MHM designed the experiment and contributed in the interpretation of patients’ data and revising of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Beni-Suef University, under committee reference number FMBSU-REC/06092019. Informed written consent was obtained from one of the parents of children prior enrollment in this study recruitment.

Consent for publication

All authors declare that they read and accept the final form of the revised manuscript before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hodeib, M.M., Ali, A.G., Kamel, N.M. et al. Impact of eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori in children with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Egypt Pediatric Association Gaz 69, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00053-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00053-3