Abstract

Background

Disturbed sleep and menstrual symptoms are prevalent health conditions with limited successful treatments. This study aimed to detect the association between sleep problems and menstrual symptoms among young women in Upper Egypt. In this cross-sectional study, 4122 young women aged 12 to 25 years and residing in Beni-Suef City were recruited using a multi-stage random method. The participants were interviewed for their premenstrual disorders, dysmenorrhea, average daily hours of sleep, and insomnia during the previous 6 months.

Results

Young women who reported sleep < 8 and < 7 h/day had more premenstrual spasm than those who slept ≥ 8 h/day: OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.5 and OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6, respectively. Hours of sleep were not associated with other menstrual symptoms. Compared with those without insomnia, young women with insomnia were more likely to report premenstrual spasm (OR 2.3, 95% CI 18–2.8), nervousness (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.9–2.8), fatigue (OR 2.9, 95% CI 2.4–3.6), headache (OR 2.6, 95% CI 2.2–3.2), breast pain (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5–2.3), weight gain (OR 2.6, 95% CI 2.0–3.3), GIT disturbance (OR 2.8, 95% CI 2.2–3.6), and dysmenorrhea (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.6–4.3).

Conclusion

Insomnia has been shown to be significantly associated with premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhea, but no substantial relationship has been indicated between hours of sleep and most menstrual symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Abnormal menstrual symptoms are common complaints among young women. Significant physical, psychological, social, educational, and occupational drawbacks were identified among women with premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhea [1, 2]. The additional healthcare payments and sick leaves related to menstrual symptoms add extra burden on the health care system [3].

At the same time, sleep disturbance has many health, behavioral, occupational, and academic consequences in otherwise healthy individuals as well as those with underlying medical conditions [4]. In comparison with men, women report more sleep disorders and pose a greater risk of insomnia [5,6,7].

A few numbers of studies investigated the relationship between sleep disorders and menstrual symptoms. One study showed that women with significant emotional premenstrual symptoms were sleepier during the late luteal phase than those with minimal symptoms [8]. Another study suggested an abnormal homeostatic regulation of the sleep-wake cycle attributed to altered melatonin secretion among women with premenstrual disorders [9]. Gupta et al. concluded that women with possible premenstrual disorders had poorer sleep than those without premenstrual disorders [10]. On the other hand, a study investigating sleep patterns in women with menstrual pain showed that menstrual pain and pain killers did not significantly affect sleep patterns [11].

However, the previous studies focused on detecting the psychomotor sleep performance and reproductive hormonal changes rather than the subjective sleep and menstrual symptoms and reached even inconclusive findings. We, therefore, conducted this study to investigate the association between each of sleep duration and insomnia with menstrual symptoms among young women in Upper Egypt.

Methods

Study design and settings

This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted on young women (12–25 years) residing in Beni-Suef City in Upper Egypt during the period between August 2016 and April 2017. Beni-Suef City is an urban metropolitan occupied surrounded by rural villages.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using the Epi-Info version 7 StatCalc, which is available from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO). After reviewing previously published reports, we chose the following: a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. In order to overcome the expected low response rate, we more than tripled the least required sample size.

Sampling methods

In this study, a multi-stage random technique was adopted. First, we classified the urban metropolitan to 3 socio-economic strata: low, middle, and high. Then, out of each stratum, we selected 2 quarters by card withdrawal, and out of each quarter, almost 100 households were chosen using a random start. Later, we stratified the rural villages geographically to North, West, and South villages, and 2 villages were selected by card withdrawal from each direction. The 6 selected villages were further clustered roughly to 3 areas, and their residents were asked to participate in the study. Eventually, a total of 6000 young women (3600 from urban areas and 2400 from rural areas) were invited to participate after the householders were briefed on the purpose and steps of the study.

Research ethics

Young women who showed their readiness to participate were asked to sign their informed consents while the guardians of young women < 18 years were asked to sign on behalf of their daughters. In addition to the acceptance of their guardians, young women < 18 years were required to give their verbal assent before participation. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Beni-Suef University.

Data collection

We interviewed all young women who experienced a menstrual period at least for 1 year using an Arabic questionnaire comprised of four sections. The first section included socio-demographic questions: age, education or work, marital status, residence, parental education, physical activity, exposure to passive smoking, and preference for salty-fatty food. The second section included gynecological history questions: circumcision, the age of menarche, menstrual flow days, and menstrual cycle duration. The third section included questions about premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhea during the previous 6 months. The premenstrual symptoms were defined as physical and emotional symptoms experienced within 7 to 10 days before menstruation. These symptoms included spasm, fatigue, headache, irritation or nervousness, breast pain, GIT disturbance, and weight gain. Dysmenorrhea was defined as a painful cramping sensation in the groin during flow days. The fourth section assessed the average hours of sleep per day in addition to insomnia during the previous 6 months. Insomnia was defined as a difficulty to initiate or maintain sleep. A scale of never, rarely, sometimes, and always was used to assess the presence of insomnia.

Statistical analyses

We used the software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc. Released 2009, PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0: SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis. Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether sleeping < 8 or < 7 or < 6 h/day in reference to sleeping ≥ 8 h and insomnia versus never to rarely insomnia could be associated with different premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhea. Only those who reported insomnia by the choices sometimes or always were considered having insomnia. The following covariates were included in the regression models: gynecological age (chronological age-age of menarche), residence, educational and occupational status, marriage, parental education, passive smoking, diet, and circumcision. The manuscript was reported according to the STROBE checklist (Additional file 1).

Results

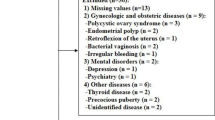

With 4122 participating young women, the response rate was 68.7%. Being not interested in participation and fear of sharing personal experiences were the main reasons for the relatively low response rate. Of the participants, 27.4% were school students, 46.3% university students, and 15.4% employees. Their mean age was 20.0 ± 3.3 years, menarche age 13.1 ± 1.4 years, gynecological age 6.9 ± 3.5 years, menstrual cycle duration 28.2 ± 6.8 days, menstrual flow days 5.2 ± 1.4, and 58.7% were circumcised. Only 19.4% reported physical activity while 46.1% reported passive smoking. Participants reported an average sleep duration of 8.3 ± 1.7 h/day and 11.6% had insomnia during the previous 6 months (Table 1).

Compared with young women who reported sleeping ≥ 8 h/day, sleeping < 8 h/day and < 7 h/days is associated with premenstrual spasm (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.5 and OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6, respectively), while sleeping < 6 h/day is associated with premenstrual fatigue (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–2.1). Sleeping hours were not related to other premenstrual symptoms or dysmenorrhea (Table 2).

On the other hand, insomnia was associated with all investigated premenstrual symptoms: spasm (OR 2.3, 95% CI 18–2.8), nervousness (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.9–2.8), fatigue (OR 2.9, 95% CI 2.4–3.6), headache (OR 2.6, 95% CI 2.2–3.2), breast pain (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5–2.3), weight gain (OR 2.6, 95% CI 2.0–3.3), and GIT disturbance (OR 2.8, 95% CI 2.2–3.6). Also, women with insomnia reported more dysmenorrhea than women without insomnia (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.6–4.3) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study indicated a significant association between insomnia and menstrual symptoms. Young women with insomnia were more likely to report premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhea. Yet, no substantial relationship was established between hours of sleep and different menstrual symptoms.

In line with our findings, Mauri et al. compared the sleeping disturbances between women with and without premenstrual syndrome and concluded that those with premenstrual syndrome had more awakenings, unpleasant dreams, and morning tiredness [12]. Baker et al. showed that dysmenorrhea significantly reduced subjective sleep quality, sleep efficiency, and rapid eye movement of young women compared with pain-free phases of the menstrual cycles of the same women and compared with controls [13]. Gupta and colleagues assessed sleep during bedtime, sleep quality, sleep-onset latency, sleep maintenance, and wake time and found that women with severe premenstrual symptoms were more likely to experience poor sleep than those without these symptoms [10]. However, Araujo et al. reported that the presence of premenstrual disorders or even the usage of medications to alleviate the subsequent spasmodic pains did not affect sleep patterns as measured by polysomnogram [11].

Theoretically, insomnia may function as an antecedent, concomitant, or consequence of severe menstrual symptoms. While sleep deprivation can lead to hormonal imbalances that disturb the menstrual cycle, the pain and stress related to menstrual symptoms can prevent good sleep [14, 15]. However, the cross-sectional design of the current study cannot answer the question of which came first sleep disturbance or menstrual problems.

Biologically, the physical and emotional changes of the menstrual cycle are controlled by several hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, and growth hormone. These hormones do not only regulate the reproductive functions but affect the circadian rhythm and sleep as well. Therefore, the disturbance of these hormones can lead to both poor sleep and menstrual irregularities [16]. Besides, physical inactivity, obesity, stress, and depressive symptoms are considered significant risk factors for both insomnia and menstrual disorders [17, 18].

Further, although detecting the prevalence of insomnia is beyond the aim of this study, our results showed that 11.6% of the young women had insomnia during the previous 6 months. In agreement with our findings, a study conducted on 554 working women in Egypt estimated the prevalence of insomnia with 12.5% [19]. The prevalence of severe insomnia ranged between 4 and 22% in 5 northern European countries and was higher in women than men [20]. Other studies showed relatively higher prevalence rates of insomnia. Among 299 young women in Switzerland, the prevalence of 2-to 3-week insomnia was 14.4% and 1-month insomnia was 31.1% [21]. More than a third of women visiting a family practice in India and more than half of women veterans receiving health care in the USA had insomnia [22, 23]. However, the previous studies were conducted on populations with dissimilar socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics and used a wide variety of insomnia definitions, assessment tools, and durations.

Although this study assessed the association between each of sleep duration and insomnia with menstrual symptoms among a large cohort of young women, some limitations should be considered. First, the assessment of sleep duration and menstrual symptoms was based on self-report during the previous 6 months which makes the study vulnerable to misclassification bias and recall bias. Second, we had no data on the nature of sleep apart from insomnia. Third, the cross-sectional design of the study cannot imply causality and cannot determine whether this relationship was unidirectional or bidirectional. Fourth, some psychological factors that could modify the association between sleep duration and menstrual symptoms such as anxiety and depression were not controlled for in the regression models. Fifth, the low response rate in addition to the high parental education rate of the participants that disagrees with the low education rate in Upper Egypt may indicate a sort of participation bias. In this regard, the cultural perspective of the participating young women should be considered. In conservative communities, such as that of Upper Egypt, emotional and psychiatric disturbances are considered taboos that people do not want to discuss. Further, women in Upper Egypt, especially young ones, feel reluctant before sharing their personal experiences with others. This could explain the low response rate and justify why the majority of participants came from educated families.

Conclusion

This study detected a significant relationship between insomnia and each of premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhea. No conclusive association was identified between sleeping hours and menstrual disorders. Future cohort studies investigating large populations are recommended.

Availability of data and materials

Available on request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Knox B, Azurah A, Grover S (2015) Quality of life and menstruation in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 27:309–314

Arafa A, Senosy S, Helmy H, Mohamed A (2018) Prevalence and patterns of dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome among Egyptian girls (12–25 years). Middle East Fertil Soc J 23:486–490

Tanaka E, Momoeda M, Osuga Y, Rossi B, Nomoto K, Hayakawa M et al (2014) Burden of menstrual symptoms in Japanese women; an analysis of medical care-seeking behavior from a survey-based study. Int J Womens Health 6:11–23

Medic G, Wille M, Hemels M (2017) Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep 9:151–161

Lindberg E, Janson C, Gislason T, Bjornsson E, Hetta J, Boman G (1997) Sleep disturbances in a young adult population: can gender differences be explained by differences in psychological status? Sleep 20:381–387

Chung K, Cheung M (2008) Sleep-wake patterns and sleep disturbance among Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Sleep 31:185–194

Settineri S, Gitto L, Conte F, Fanara G, Mallamace D, Mento C et al (2012) Mood and sleep problems in adolescents and young adults: an econometric analysis. J Ment Health Policy Econ 15:33–41

Lamarche L, Driver H, Wiebe S, Crawford L, DE Koninck J (2007) Nocturnal sleep, daytime sleepiness, and napping among women with significant emotional/behavioral premenstrual symptoms. J Sleep Res 16:262–268

Shechter A, Lespérance P, Ng Ying Kin N, Boivin D (2012) Nocturnal polysomnographic sleep across the menstrual cycle in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Sleep Med 13:1071–1078

Gupta R, Lahan V, Bansal S (2012) Subjective sleep problems in young women suffering from premenstrual dysphoric disorder. N Am J Med Sci 4:593–595

Araujo P, Hachul H, Santos-Silva R, Bittencourt L, Tufik S, Andersen M (2011) Sleep pattern in women with menstrual pain. Sleep Med 12:1028–1030

Mauri M, Reid R, MacLean A (1988) Sleep in the premenstrual phase: a self-report study of PMS patients and normal controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand 78:82–86

Baker F, Colrain I (2010) Daytime sleepiness, psychomotor performance, waking EEG spectra and evoked potentials in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. J Sleep Res 19:214–227

Baker F, Driver H, Rogers G, Paiker J, Mitchell D (1999) High nocturnal body temperatures and disturbed sleep in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Am J Physiol 277:1013–1021

Leproult R, Van Cauter E (2009) Role of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolism. Endocr Dev 17:11–21

Driver H, Baker F (1998) Menstrual factors in sleep. Sleep Med Rev 2:213–229

Gindoff P (1989) Menstrual function and its relationship to stress, exercise, and body weight. Bull N Y Acad Med 65:774–786

Bae J, Park S, Kwon J (2018) Factors associated with menstrual cycle irregularity and menopause. BMC Womens Health 18:36

Arafa A, Khamis Y, Hassan H, Saber N, Abbas A (2018) Epidemiology of dysmenorrhea among workers in Upper Egypt; a cross sectional study. Mid East Fert Soc J 23:44–47

Chevalier H, Los F, Boichut D, Bianchi M, Nutt D, Hajak G et al (1999) Evaluation of severe insomnia in the general population: results of a European multinational survey. J Psychopharmacol 13:21–24

Buysse D, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W (2008) Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep 31(4):473–480

Bakhshani N, Mousavi M, Khodabandeh G (2009) Prevalence and severity of premenstrual symptoms among Iranian female university students. J Pak Med Assoc 59:205–208

Martin J, Schweizer C, Hughes J, Fung C, Dzierzewski J, Washington D et al (2017) Estimated prevalence of insomnia among women veterans: Results of a postal survey. Womens Health Issues 27:366–373

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA provided the idea and contributed to the data collection, manuscript writing, and analysis. OM, EA, and AM contributed to the data collection and manuscript writing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Beni-Suef University (August 2016). No. BSU 2016/23_1

Women who showed their readiness to participate were asked to sign their informed consents while the guardians of young women < 18 years were asked to sign on behalf of their daughters. In addition to the acceptance of their guardians, young women < 18 years were required to give their verbal assent before participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

STROBE checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Arafa, A., Mahmoud, O., Abu Salem, E. et al. Association of sleep duration and insomnia with menstrual symptoms among young women in Upper Egypt. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 27, 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-019-0011-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-019-0011-x