Abstract

Background

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition with varied presentation, which ultimately leads to chronic pelvic pain and infertility. It is a psychological and economic burden to the women and their families.

Main body of abstract

The literature search was performed on the following databases: MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Scopus, EMBASE, Global health, the COCHRANE library, and Web of Science. We searched the entirety of those databases for studies published until July 2020 and in English language. The literature search was conducted using the combination of the Medical Subject heading (MeSH) and any relevant keywords for “endometriosis related infertility and management” in different orders. The modalities of treatment of infertility in these patients are heterogeneous and inconclusive among the infertility experts. In this article, we tried to review the literature and look for the evidences for management of infertility caused by endometriosis. In stage I/II endometriosis, laparoscopic ablation leads to improvement in LBR. In stage III/IV, operative laparoscopy better than expectant management, to increase spontaneous pregnancy rates. Repeat surgery in stage III/IV rarely increases fecundability as it will decrease the ovarian reserve, and IVF will be better in these patients. The beneficial impact of GnRH agonist down-regulation in ART is undisputed. Dienogest is an upcoming and new alternative to GnRH agonist, with a better side effect profile. IVF + ICSI may be beneficial as compared to IVF alone. Younger patients planned for surgery due to pain or any other reason should be given the option of fertility preservation.

Short conclusion

In women with endometriosis-related infertility, clinician should individualize management, with patient-centred, multi-modal, and interdisciplinary integrated approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Endometriosis is a state of chronic inflammation in the pelvis and is characterized by endometrial-type tissue outside of the uterus. Although exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown, it roughly affects 2 to 10% of the female population, but 30 to 45% of females with infertility [1]. This condition leads to two main problems—pain, infertility, or both. Endometriosis also has significant impact on the quality of life of the patients and negative influence on the sexual function and interpersonal relationships. This article will deal with endometriosis-related infertility in detail.

Main text

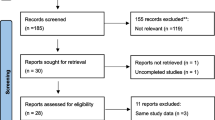

The literature search was performed on the following databases: MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Scopus, EMBASE, Global health, the COCHRANE library, and Web of Science. We searched the entirety of those databases for studies published until July 2020 and in English language. The literature search was conducted using the combination of the following Medical Subject heading (MeSH) and any relevant keywords in different orders: “endometriosis”, “endometrioma”, “endometriotic cystectomy”, “diagnosis”, “grading”, “management”, “surgical management”, “medical management”, “fertility preservation”, “mechanism”, “infertility”, “pathophysiology”, “ASRM classification”, “Endometriosis fertility index (EFI)”, “ovulation induction”, “intrauterine insemination (IUI)”, “Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH)”, “Assisted reproduction Techniques (ART)”, “In vitro fertilization (IVF)”, “clinical pregnancy rate”, “Dienogest”, “GnRH agonist”, “live birth”, “pregnancy outcome”, “minimal-mild endometriosis”, “severe endometriosis”, and “decreased ovarian reserve”. The reference lists of the included studies were also checked to look for studies that were not found in the electronic literature search. A total of 2208 articles were found pertaining to endometriosis. Original articles and some review articles, published in recent 5 years, were given priority. All the articles were accessible in full text. In this review, individual data sources were not sought for, and a descriptive analysis was done. The data were summarized in a form of descriptive review.

Diagnosis of endometriosis

The main symptoms of endometriosis are chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, infertility, and cyclical bowel or urinary complaints. It is often missed at young age because of the non-specific complaints, causing a long diagnostic delay [2]. The imaging modality of choice is transvaginal sonography (TVS) which can detect both ovarian endometrioma, rectal endometriosis, and associated adenomyosis [3]. In case of doubt in the diagnosis of ovarian endometrioma on TVS, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used, but its diagnostic accuracy is limited for peritoneal endometriosis [4, 5]. Further, evaluation for the involvement of other organs should be done if history and examination suggest deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). MRI or CT abdomen may help in evaluation when there is clinical suspicion of other organs being affected like ureter, bladder, and/or bowel [6]. More specific investigations like CT urogram or transrectal sonography may be required for mapping the endometriosis prior to surgery to see involvement of ureter or bladder and bowel respectively [7, 8]. There have been extensive studies on biomarkers (including CA125) for endometriosis; none has been validated for diagnosis of endometriosis [5].

The use of diagnostic laparoscopy and histopathological confirmation of endometrial glands and stromal tissue is gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis, but since the advancement of imaging, laparoscopy only to diagnose endometriosis may not be required. Quality of laparoscopy depends on surgical skills, expertise, and experience. Retroperitoneal and localized vaginal endometriosis can be easily missed. A negative laparoscopy reliably excludes the diagnosis of endometriosis, but positive laparoscopy is less informative and of limited value when used in isolation without histology [9, 10]. Negative histology also does not exclude endometriosis [5] due to the possibility of inadequate or squeezed samples, which may have been taken from wrong location.

Grading of endometriosis

In 1996, ASRM proposed a revised classification of endometriosis and is currently the most widely used grading system for severity of endometriosis, but it has many limitations [11]. It does not correlate with the severity of symptoms, does not predict the treatment outcome, and poorly correlates with the pregnancy outcomes. Endometriosis fertility index (EFI) was developed by Adamson and Pasta [12], to address this problem. This system helps in predicting the treatment outcomes in infertile patients with laparoscopically proven endometriosis attempting standard non-IVF conception.

Vesali et al. conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the accuracy of EFI for predicting non-ART pregnancies. There was a significant difference between all categories, especially EFI 0-2 had a cumulative non-ART pregnancy rate at 36 months of 10%, which increased to approximately 70% for EFI of 9–10 (P < 0.001). They concluded that EFI was a useful index in predicting the non-ART pregnancy rate [13]. Though developed for calculating the non-IVF pregnancy rate, prediction studies have shown that EFI is better at predicting the IVF outcomes as well [14]. This system does not account for uterine abnormality like presence of adenomyosis along with endometriosis, which is very common in infertile patients. Uterine pathology should be included in the system and for predicting pregnancy rate. Further, it does not help in prediction of post-surgery endometriosis-associated pain [12]. Moreover, EFI can be calculated for only those patients who underwent surgery. It is recommended that all women with endometriosis have the r-ASRM classification, and patients with infertility should have EFI [15]. This classification and scoring system helps in counselling and prognosticating the patients about the treatment options and the outcomes expected.

Mechanism of infertility in endometriosis

The factors responsible for sub-fertility in endometriosis have been attributed to distorted pelvic anatomy and molecular alteration leading to excess production of prostaglandins, oestrogen, growth factors, reactive oxygen species, cytokines, etc. [16]. There is a debate on how minimal or mild endometriosis can lead to infertility without distorting the pelvic anatomy. Various studies have shown that the molecular alterations in endometriosis lead to ovarian, tubal, or endometrial dysfunction, which leads to infertility [17,18,19]. The progesterone resistance and hyperestrogenic state lead to chronic inflammation making the endometrium non-receptive for normal embryo implantation and has been suggested as a significant contributor to infertility [20]. In women with endometriosis, inflammatory markers present in peritoneal fluid hamper oocyte competence; impair sperm motility, function, and oocyte-sperm interaction; and can cause sperm DNA fragmentation and abnormal acrosome reaction [21]. Xu et al. found that even in minimal to mild endometriosis, oocyte quality is impaired because the mitochondrial structure and function are hampered [22]. Immunological dysfunction is seen in infertile women with endometriosis [23]. Adenomyosis is associated with endometriosis in 90% of cases [24]. Surgeries performed for endometriosis lead to decreased ovarian reserve and pelvic adhesions contributing to infertility. In endometriosis, the granulosa cells are resistant to luteinizing hormone (LH) to some extent; there is hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis dysfunction with abnormal LH production [25], which affects ovulation. Hyperprolactinemia may be associated with endometriosis and its progression, with a significant association between the severity of endometriosis and prolactin levels [26]. So, distorted tubo-ovarian relationship, impaired folliculogenesis, hormonal dysfunction, disturbed local milieu, fertilization failure, and impaired endometrial receptivity are causes of endometriosis-related infertility.

Medical management of infertility

The treatment of endometriosis-related infertility must be individualized. Medical, surgical, and ART treatment alone or combinations can be used in these patients.

Medical management, which includes various hormonal treatments, deals with ovulation suppression and, therefore, does not have much role for infertility treatment. This is useful for only pain relief in infertile women. Cochrane review by Hughes et al. concluded that there is no role for suppressing ovulation in women with endometriosis who plan to conceive [27]. Neither preoperative nor postoperative hormonal therapy increases the chances of spontaneous conception [27, 28]. The Cochrane review which included three RCTs, a total of 165 patients, showed the benefit of GnRH agonist pre IVF. The authors concluded that odds of clinical pregnancy in endometriosis patients increased by fourfold when GnRH agonists were given for 3–6 months before IVF or ICSI [29]. GnRH agonists should be given for 3–6 months prior to IVF as per ESHRE recommendations to increase the clinical pregnancy rates [5].

In recent years, numerous studies have been done to find out the role of dienogest in treating endometriosis-related infertility. Dienogest has an effect on multiple receptors like the oestrogen, androgen, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid and little impact on the metabolic parameters, and is having a significant impact on endometriotic lesions locally [30]. A systematic review by Grandi et al. in 2016 analysed studies on dienogest therapy and its effects on the inflammatory reaction of endometriotic tissue [31]. Dienogest is anti-inflammatory and causes modulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production, which is mediated via PR in progesterone receptor-expressing epithelial cells.

Muller et al. conducted study on 144 women planned for IVF after their endometriotic cystectomy and recruited the patients prospectively [32]. They divided patients into three groups: those receiving dienogest, GnRH agonist, and those without hormonal therapy within 6 months before IVF. They concluded that pre-IVF hormonal treatment is required in patients with endometriosis, and dienogest will probably be a better pre-treatment option as compared to GnRH agonist. Tamura et al. conducted a study on subjects with stage III or IV endometriosis, recruited 68 women in two groups: dienogest (n = 33) and control group (n = 35) [33]. Dienogest was given for 3 months prior to the ART cycle followed by GnRH agonist long protocol for ovarian stimulation. They concluded that administering Dienogest just before IVF did not increase IVF success rates. Therefore, more extensive studies are required to see whether dienogest therapy before IVF can help improve the clinical outcome of patients.

Surgical management

The decision for surgery in endometriosis-associated infertility depends on age, previous ovarian surgery, ovarian reserve, duration of infertility, grade of endometriosis, tubal status, cost of treatment, expected outcome of the procedure, and priorities of the patient. The reconstruction of the normal pelvic anatomy to achieve an excellent tubo-ovarian relationship and remove all macroscopically visible disease is the main aim of the surgery. Minimally invasive surgery is preferred over laparotomy for obvious reasons [34].

Leonardi et al. conducted a meta-analysis to determine if operative laparoscopy is an effective treatment in grade I-IV endometriosis compared with other therapies [10]. They found 1990 studies that were included in the analysis. When operative laparoscopy was compared with diagnostic, it was found that operative did not improve the clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) (p = 0.06).

Surgery for minimal to mild endometriosis

There are two ways of removing peritoneal endometriotic lesions, first is by excision or ablation; both have comparable cumulative pregnancy rates. Ablative techniques involve bipolar coagulation and laser methods like CO2 or argon laser. ESHRE recommends CO2 laser vaporization is better than monopolar electrocoagulation [5]. Cochrane review by Duffy et al. has reported higher live birth or ongoing pregnancy rates and reduced overall pain scale after laparoscopic surgery for mild-moderate endometriosis [35]. ESHRE concluded that the ongoing pregnancy rates are increased in infertile women with AFS/ASRM stage I/II endometriosis after laparoscopy. Excision or ablation of endometriotic lesions on laparoscopy is better than diagnostic laparoscopy alone. Surgical removal of peritoneal endometriosis may prevent the progression of the disease further [36].

Surgery for moderate to severe endometriosis

Moderate to severe endometriosis (r-ASRM III-IV) distorts normal pelvic anatomy; surgery restores this distorted pelvic anatomy and the tubo-ovarian relationship hampered because of the pelvic adhesions. This form of endometriosis may involve rectovaginal or colorectal and can be deep infiltrating endometriosis [37].

Maheux-Lacroix et al. conducted retrospective study on women with stage III–IV endometriosis who attempted pregnancy after laparoscopic resection; 63% had live birth following surgery, 64% without ART. EFI was significantly correlated with live-births (P < 0.001). EFI of 0–2 vs. 9–10, cumulative non-ART LBR at 5 years was 0%VS 91%, which was statistically significant. The chance of having live birth steadily increased from 38 to 71% among the same EFI strata in women who attempted ART (P = 0.1) [38].

A significant problem after any pelvic surgery is post-operative adhesion formation. Oxidized regenerated cellulose during operative laparoscopy for endometriosis has been proved useful for prevention of adhesion formation [5]. After laparoscopic surgery, suspending the ovary temporarily will help reduce post-operative ovarian adhesions in cases with severe pelvic endometriosis. A recent meta-analysis concluded that there is a reduced chance and severity of adhesion formation in patients with stage III–IV endometriosis if the ovaries are temporarily suspended post laparoscopic resection [39].

Ovarian endometrioma

Clinical data has suggested that ovarian endometrioma damages surrounding healthy ovarian tissue. The pathophysiology of which may be the presence of proteolytic enzyme, inflammatory mediators, reactive oxygen species, and iron in concentrations many times higher than those present in serum or other types of cysts; all of these lead to cell damage. The decision to operate on ovarian endometrioma depends on the patient’s age, ovarian reserve, and prior surgery on the ovary [37]. Depending on surgical skill, patient profile, and resources available ovarian endometrioma can be managed by either laparotomy or laparoscopy, with excision of endometrioma capsule or drainage and ablation (electrocautery, CO2 laser, or plasma energy) of cyst wall [5]. Recent prospective study concluded that there was no difference in post-operative pregnancy rates after either ablation using plasma energy or cystectomy of the ovarian endometrioma [40]. Both techniques can compromise ovarian reserve, excision by removal, and coagulation by thermal damage of normal ovarian tissue. In infertility patients, accepting the increased chance of recurrence due to incomplete treatment of ovarian lesions is better than severe reduction of ovarian reserve following complete resection of endometriomas. A less damaging approach in terms of ovarian reserve for large endometrioma is a three-step approach. This includes laparoscopic drainage of endometrioma, followed by the use of GnRH for 3 months to reduce cyst diameter, and then laparoscopic CO2 laser vaporization of the cyst [41].

Surgery before Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART)

It was discussed in the previous section; spontaneous pregnancy rates can improve with surgery for endometriosis. There have not been prospective, randomized studies on the effects of surgery for endometriosis on ART outcomes. A retrospective study on women with minimal-mild endometriosis had shown that surgery before IVF resulted in significantly higher implantation, pregnancy, and live birth rate (LBR) [42]. Bianchi et al., in their study in women with DIE, found that extensive laparoscopic excision of endometriotic lesions before ART improves pregnancy rate, but LBR did not differ [43]. Another study found that surgery in patients with DIE did not improve IVF outcomes [44]. A retrospective study done on 115 patients has shown that spontaneous conception rate and IVF outcome improves after laparoscopic excision of DIE in moderate to severe endometriosis [45]. Retrospective analysis of 110 colorectal endometriosis patients showed that cumulative LBR at the first ART cycle after surgery as compared to the first-line ART was 33% vs. 13.0% [46]. There has been no evidence to support endometrioma removal before IVF as it does not enhance the outcome; instead, it can lead to decreased ovarian reserve and increase the dose of gonadotropins for stimulation in ART. Cochrane review showed no difference in clinical pregnancy rate with either surgery or expectant management before ART [47]. Liang et al. conducted a prospective study where women with endometriosis-associated infertility were recruited; 13 had surgery to remove the endometrioma before IVF, and 28 did not undergo surgery [48]. The chemokines, growth factors, inflammatory mediators, implantation rate, and CPR were similar between the surgery and non-surgery groups. Ovarian reserve in terms of AMH levels was lower in the surgery group. Magnien et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study in which IVF outcomes were evaluated for patients with and without previous surgery for Endometriosis. Past history of surgery for endometriosis (p = 0.001) was an independent risk factor for lower pregnancy rates [49]. But, in cases where normal ovarian tissue is not accessible for oocyte retrieval, cystectomy may be considered [5]. In diminished ovarian reserve patients, preoperative embryo cryopreservation followed by laparoscopic surgery (“surgery-assisted-IVF combination/Hybrid therapy”) can be done [50]. Table 1 summarizes surgery vs ART in endometriosis.

Medically assisted reproduction

Medically assisted reproduction (MAR) includes ovulation induction, controlled ovarian stimulation (COS), ovulation triggering, ART procedures, and intrauterine (IUI), intracervical, and intravaginal insemination as per World Health Organization (WHO) Revised Glossary on ART Terminology. Young women with minimal to mild disease and short duration of infertility can be managed expectantly for 6–9 months [51] If the above treatments fail or in patients with long standing infertility, diminished ovarian reserve, or in cases with compromised tubal function or male factor infertility, IVF should be considered [52].

Controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) and intrauterine insemination (IUI)

COS and IUI is a cost-effective and first-line treatment for many types of infertility, but its utility is not entirely clear in endometriosis. A retrospective analysis of COS and IUI demonstrated a per cycle fecundity rate of 6%, 11.8%, and 15.3% for endometriosis, malefactor, and unexplained infertility, respectively [53]. A meta-analysis has shown that endometriosis decreases the odds of pregnancy by half [54]. Keresztúri et al. compared pregnancy rate after COS+IUI on 238 patients of all stages of endometriosis and concluded that surgery followed by COH+IUI is more effective than surgery alone [55]. So, COS with IUI can be considered as a first-line strategy for infertile women with early-stage endometriosis. Aromatase inhibitors (AI) and clomiphene citrate both can be used for COS in women who underwent surgery for minimal to mild endometriosis. In a study, a small group of surgically diagnosed endometriosis patients were randomized to OVI with human menopausal gonadrotrophin (HMG) + IUI vs no treatment for four cycles showed that cumulative live birth rate over 4 cycles was 11% versus 2% (p=0.002) suggesting that COH may improve pregnancy rates [56]. A multicenter trial included patients with unexplained infertility, endometriosis, or mild male factor infertility and who were randomized to intracervical insemination (ICI), IUI, FSH with ICI, or FSH with IUI [57]. They concluded that FSH +IUI had higher pregnancy rates than the other groups (33% v 10%, p <0.0001) and suggested that in a woman with endometriosis and subfertility, it may be reasonable to start with OVI + IUI. A retrospective study by Houwen et al., who performed IUI in moderate-to-severe endometriosis patients, found that long-term pituitary down-regulation prior to OVI+IUI tend to result in higher ongoing pregnancy rate (adjusted HR 1.8) [58]. A larger RCT is required to see the utility of OVI+IUI in moderate to severe endometriosis, at present not recommended.

Endometriosis and assisted reproductive technology (ART)

ESHRE recommends using ART in endometriosis if there is tubal or male factor infertility, and/or other treatments have failed. Studies to date on effect of endometriosis on IVF outcome have shown mixed results. After a meta-analysis, Senapati et al. concluded that women with endometriosis who undergo IVF have half the pregnancy rate compared to those who get IVF done for other indications [59]. Ovarian endometrioma, its surgery, and peritoneal endometriosis damage oocyte maturation and adversely affect the ovarian reserve, which leads to inadequate ovarian response [59]. Data suggests that endometriosis affects not only the endometrial receptivity but also the oocyte and embryo development [59]. However, other studies have shown that endometriosis in isolation has LBR after IVF similar to other causes of infertility [60]. A recent meta-analysis which included 36 studies has shown that women with and without endometriosis have comparable ART outcomes in terms of live births. In contrast, those with severe endometriosis have inferior outcomes [61]. A retrospective cohort study on approximately 3600 women with endometriosis and 19,000 women as control has shown that there was not much difference in terms of live birth, clinical pregnancy, and miscarriage rates. Still, women with endometriosis had a lesser number of oocytes retrieved [60].

Various studies have been done to compare the efficacy of GnRH agonist and antagonist in endometriosis patients. GnRH agonists suppress the endometriotic lesions and are thought to increase the IVF success rate. A prospective randomized trial by Recai et al. reported that implantation and CPR are similar for patients with mild to moderate endometriosis with both agonist and antagonist protocols and endometrioma who did not undergo surgery for endometriosis. However, GnRH agonists had a significantly higher number of surplus embryos available for cryopreservation [62]. Kolanska et al. has done a retrospective analysis of prospective data of 284 COH cycles, 165 with GnRH-agonist and 119 with GnRH-antagonist protocol. The pregnancy rate was similar in both groups while the live-birth rate was higher in the agonist group [63]. In the study by Zhao et al., patients were divided into three groups according to the IVF protocols, GnRH-agonist, GnRH-antagonist, and long GnRH-agonist. Total gonadotrophin dosage and duration required for stimulation was less in the GnRH-antagonist group than in the others. Still, there were no significant differences in the implantation rate and clinical pregnancy rate, oocytes retrieved, fertilization rate, embryo utilization rate, and LBR in the three groups [64].

ESHRE recommends, IVF pretreatment with GnRH agonist for a period of 3–6 months [29]. For COS in endometriosis patients both agonist and antagonist protocols seem to be equally effective [65]. A study suggests that GnRHa agonist ovulation triggering, which is possible in antagonist protocols, limits pain symptom progression in the period immediately after ART [66].

In women with endometriosis, there are increased chances of ovarian abscess formation following oocyte pickup; although overall risk is low, antibiotic prophylaxis has been suggested [5]. Boucret et al. conducted a retrospective study intending to evaluate the impact of endometriosis on embryo quality and IVF outcomes. There was no association between endometriosis and the number of top-quality embryos, but the implantation rate and LBR were lower in the endometriosis group. The lower number of cryopreserved embryos decreases the cumulative LBR by reducing number of embryos, not their quality [67]. Lower implantation rate after IVF in endometriosis patients compared to tubal factor and unexplained infertility patients may be due to the association of endometriosis and adenomyosis. Prolonged downregulation with GnRH agonist or oral contraceptive pills may help overcome the negative effect of adenomyosis on implantation and endometrial receptivity [68].

Recent research favours IVF/ICSI over IVF alone in endometriosis patients. Komsky-Elbaz et al. compared conventional IVF versus IVF-ICSI in sibling oocytes from couples with endometriosis and normozoospermic semen; a total of 786 sibling cumulus-oocyte complexes (COC) were randomized between insemination by conventional IVF or ICSI. The authors concluded that ICSI has higher fertilization rate and reduced rate of total fertilization failure [69]. Therefore, IVF/ICSI can be considered as a practical approach for managing endometriosis-associated infertility. Wu et al. conducted a retrospective study and found that implantation, clinical pregnancy, and LBR were statistically significantly higher in the freeze-all group compared with new transfer groups (P < 0.001) [70].

Yilmaz et al. conducted a retrospective study and found that between unilateral and bilateral endometrioma groups, AMH, oocyte, and embryo quality, the numbers of embryos, PR, and LBR are similar. They concluded that the presence of endometrioma negatively effects fertility parameters but whether it is unilateral or bilateral does not affect the outcome [71]. There has been a concern of increased recurrence rate of endometriosis after COS for IVF/ICSI due to the supra-physiologic surge of E2. Some studies suggested that endometriosis recurrence rates are not increased after COS for IVF/ICSI [52]. Studies have proven that ART did not exacerbate the symptoms of endometriosis or negatively impact quality of life [72]. Table 2 summarizes guidelines/recommendations in endometriosis-related infertility.

Fertility Preservation in Endometriosis

The technique of ovarian tissue, oocyte, and embryo cryopreservation is widely used in oncology patients for fertility preservation (FP). Therefore, oocyte and embryo cryopreservation can be good options for fertility preservation in young endometriosis patients at risk of premature ovarian failure. The women with endometriosis may benefit from fertility preservation, but because of the paucity of data, fertility preservation counselling of patients with endometriosis should be individualized. Cobo et al. conducted a retrospective observational study to observe the outcome of FP using cryopreserved oocytes in patients with endometriosis with or without a history of surgery [75]. They found that patients without a history of surgery had a higher number of cryopreserved oocytes per cycle than the unilateral or bilateral surgery groups, but was comparable among the surgical patients. Fertility preservation gives patients with endometriosis a chance to increase their reproductive chances. Therefore, performing surgery after oocyte pickup for FP in young women is a good option [75].

Conclusions

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease, and so is its treatment. The data on various modalities of treatment of infertility in these patients is heterogeneous and inconclusive. Medical treatment is not helpful for the treatment of infertility. ART has emerged as a ray of hope for infertile endometriosis patients where conception by other means is difficult. But the beneficial effect of GnRH agonist downregulation in ART is undisputed. Dienogest is an upcoming/new alternative to GnRH agonist, with a better side effect profile. IVF/ICSI may be a better option than IVF alone. With the current evidence available, role of surgery prior to ART is inconclusive. Patients with endometriosis-related infertility should be offered the option of fertility preservation. Randomized, prospective studies in relation to endometriosis-related infertility are lacking. For women presenting with main complaint of infertility, the clinician should individualize the management, with patient-centred, multi-modal and interdisciplinary integrated approach.

Availability of data and materials

Scoping review of the literature is available in the following databases: MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Scopus, EMBASE, Global health, the COCHRANE library, and Web of Science.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Assisted reproductive techniques

- IVF/ICSI:

-

In vitro fertilization/intra-cytoplasmic sperm insemination

- GnRH:

-

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone

- EFI:

-

Endometriosis fertility index

- IUI:

-

Intrauterine insemination

- COH:

-

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation

- TVS:

-

Transvaginal sonography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- DIE:

-

Deep infiltrating endometriosis

- ASRM:

-

American Society of Reproductive Medicine

- AFS:

-

American Fertility Society

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- COC:

-

Cumulus-oocyte complexes

- LBR:

-

Live birth rate

- OVI:

-

Ovulation induction

- ESHRE:

-

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- FP:

-

Fertility preservation

- MAR:

-

Medically assisted reproduction

- COS:

-

Controlled ovarian stimulation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- CPR:

-

Clinical pregnancy rate

- AMH:

-

Antimullerian hormone

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptors

- CPR:

-

Clinical pregnancy rate

- COC:

-

Cumulus oocyte complexes

References

Meuleman C, Vandenabeele B, Fieuws S, Spiessens C, Timmerman D, D'Hooghe T (2009) High prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women with normal ovulation and normospermic partners. Fertil Steril 92(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.056 Epub 2008 Aug 5. PMID: 18684448

Ghai V, Jan H, Shakir F, Haines P, Kent A (2020) Diagnostic delay for superficial and deep endometriosis in the United Kingdom. J Obstet Gynaecol 40(1):83–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1603217 Epub 2019 Jul 22. PMID: 31328629

Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, Valentin L, Leone FPG, Van Schoubroeck D et al (2016) Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 48(3):318–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.15955 Epub 2016 Jun 28. PMID: 27349699

Stratton P, Winkel C, Premkumar A, Chow C, Wilson J, Hearns-Stokes R et al (2003) Diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathologic examination for the detection of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 79(5):1078–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00155-9 PMID: 12738499

Dunselman GAJ, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge C, D’Hooghe T, De Bie B et al (2014) ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 29(3):400–412. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det457 Epub 2014 Jan 15. PMID: 24435778

Chapron C, Tosti C, Marcellin L, Bourdon M, Lafay-Pillet M-C, Millischer A-E et al (2017) Relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of adenomyosis and endometriosis phenotypes. Hum Reprod 32(7):1393–1401. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex088 PMID: 28510724

Bazot M, Malzy P, Cortez A, Roseau G, Amouyal P, Daraï E (2007) Accuracy of transvaginal sonography and rectal endoscopic sonography in the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 30(7):994–1001. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.4070 PMID: 17992706

Zannoni L, Del Forno S, Coppola F, Papadopoulos D, Valerio D, Golfieri R et al (2017) Comparison of transvaginal sonography and computed tomography–colonography with contrast media and urographic phase for diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis of the posterior compartment of the pelvis: a pilot study. Jpn J Radiol 35(9):546–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-017-0665-4 Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 28702886

Bafort C, Beebeejaun Y, Tomassetti C, Bosteels J, Duffy JM (2020) Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:CD011031. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub3 PMID: 33095458

Leonardi M, Gibbons T, Armour M, Wang R, Glanville E, Hodgson R et al (2020) When to do surgery and when not to do surgery for endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 27(2):390–407.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.10.014 Epub 2019 Oct 31. PMID: 31676397

American Society for Reproductive (1997) Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril 67(5):817–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x PMID: 9130884

Adamson GD, Pasta DJ (2010) Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil Steril 94(5):1609–1615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.035 PMID: 19931076

Vesali S, Razavi M, Rezaeinejad M, Maleki-Hajiagha A, Maroufizadeh S, Sepidarkish M (2020) Endometriosis fertility index for predicting non-assisted reproductive technology pregnancy after endometriosis surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 127(7):800–809

Wang W, Li R, Fang T, Huang L, Ouyang N, Wang L et al (2013) Endometriosis fertility index score maybe more accurate for predicting the outcomes of in vitro fertilisation than r-AFS classification in women with endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 11:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-112 PMID: 24330552; PMCID: PMC3866946

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, Keckstein J, Taylor HS, Abrao MS et al (2017) World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 32(2):315–324. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew293 Epub 2016 Dec 5. PMID: 27920089

de Ziegler D, Borghese B, Chapron C (2010) Endometriosis and infertility: pathophysiology and management. Lancet 376(9742):730–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60490-4 PMID: 20801404

Kobayashi H, Yamada Y, Kanayama S, Furukawa N, Noguchi T, Haruta S et al (2009) The role of iron in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol 25(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590802366204 PMID: 19165662

Singh AK, Chattopadhyay R, Chakravarty B, Chaudhury K (2013) Markers of oxidative stress in follicular fluid of women with endometriosis and tubal infertility undergoing IVF. Reprod Toxicol 42:116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.08.005 Epub 2013 Aug 29. PMID: 23994512

Sanchez AM, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Panina-Bordignon P, Vercellini P, Candiani M (2014) The distinguishing cellular and molecular features of the endometriotic ovarian cyst: from pathophysiology to the potential endometrioma-mediated damage to the ovary. Hum Reprod Update 20(2):217–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt053 Epub 2013 Oct 14. PMID: 24129684

Lessey BA, Kim JJ (2017) Endometrial receptivity in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis: it is affected, and let me show you why. Fertil Steril 108(1):19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.031 Epub 2017 Jun 14. PMID: 28602477; PMCID: PMC5629018

Carli C, Leclerc P, Metz CN, Akoum A (2007) Direct effect of macrophage migration inhibitory factor on sperm function: possible involvement in endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertil Steril 88(4 Suppl):1240–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.002 Epub 2007 Jul 20. PMID: 17658526

Xu B, Guo N, Zhang X, Shi W, Tong X, Iqbal F et al (2015) Oocyte quality is decreased in women with minimal or mild endometriosis. Sci Rep 5(1):10779

Miller JE, Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Khalaj K, Koti M, Tayade C (2017) Implications of immune dysfunction on endometriosis associated infertility. Oncotarget 8(4):7138–7147. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12577 PMID: 27740937; PMCID: PMC5351695

Kunz G, Beil D, Huppert P, Noe M, Kissler S, Leyendecker G (2005) Adenomyosis in endometriosis—prevalence and impact on fertility. Evidence from magnetic resonance imaging. Hum Reprod 20(8):2309–2316. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dei021 Epub 2005 May 26. PMID: 15919780

Cahill DJ, Harlow CR, Wardle PG (2003) Pre-ovulatory granulosa cells of infertile women with endometriosis are less sensitive to luteinizing hormone: reduced LH sensitivity in endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol 49(2):66–69. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0897.2003.01156.x PMID: 12765343

Cahill DJ (2000) Pituitary-ovarian dysfunction and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 6(1):56–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/6.1.56 PMID: 10711830

Hughes E, Brown J, Collins JJ, Farquhar C, Fedorkow DM, Vanderkerchove P (2007) Ovulation suppression for endometriosis for women with subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007(3):CD000155. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000155.pub2 PMID: 17636607; PMCID: PMC7045467

Furness S, Yap C, Farquhar C, Cheong YC (2004) Pre and post-operative medical therapy for endometriosis surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(3):CD003678. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003678.pub2 Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11:CD003678. PMID: 15266496; PMCID: PMC6984629

Georgiou EX, Melo P, Baker PE, Sallam HN, Arici A, Garcia-Velasco JA et al (2019) Long-term GnRH agonist therapy before in vitro fertilisation (IVF) for improving fertility outcomes in women with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019(11):CD013240. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013240.pub2 PMID: 31747470; PMCID: PMC6867786

Köhler G, Faustmann TA, Gerlinger C, Seitz C, Mueck AO (2010) A dose-ranging study to determine the efficacy and safety of 1, 2, and 4 mg of dienogest daily for endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 108(1):21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.020 Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(3):257. PMID: 19819448

Grandi G, Mueller M, Bersinger NA, Cagnacci A, Volpe A, McKinnon B (2016) Does dienogest influence the inflammatory response of endometriotic cells? A systematic review. Inflamm Res 65(3):183–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-015-0909-7 Epub 2015 Dec 9. PMID: 26650031

Muller V, Kogan I, Yarmolinskaya M, Niauri D, Gzgzyan A, Aylamazyan E (2017) Dienogest treatment after ovarian endometrioma removal in infertile women prior to IVF. Gynecol Endocrinol 33(sup1):18–21

Tamura H, Yoshida H, Kikuchi H, Josaki M, Mihara Y, Shirafuta Y et al (2019) The clinical outcome of Dienogest treatment followed by in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in infertile women with endometriosis. J Ovarian Res 12(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-019-0597-y PMID: 31831028; PMCID: PMC6909621

Vercellini P, Somigliana E, Vigano P, Abbiati A, Barbara G, Crosignani PG (2009) Surgery for endometriosis-associated infertility: a pragmatic approach. Hum Reprod 24(2):254–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den379 Epub 2008 Oct 23. PMID: 18948311

Duffy JM, Arambage K, Correa FJ, Olive D, Farquhar C, Garry R et al (2014) Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD011031. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub2 Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10:CD011031. PMID: 24696265

Healey M, Ang WC, Cheng C (2010) Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a prospective randomized double-blinded trial comparing excision and ablation. Fertil Steril 94(7):2536–2540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.044 Epub 2010 Mar 31. PMID: 20356588

Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P (2019) Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 15(11):666–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0245-z Epub 2019 Sep 5. PMID: 31488888

Maheux-Lacroix S, Nesbitt-Hawes E, Deans R, Won H, Budden A, Adamson D et al (2017) Endometriosis fertility index predicts live births following surgical resection of moderate and severe endometriosis. Hum Reprod 32(11):2243–2249. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex291 PMID: 29040471

Giampaolino P, Della Corte L, Saccone G, Vitagliano A, Bifulco G, Calagna G et al (2019) Role of ovarian suspension in preventing postsurgical ovarian adhesions in patients with stage III-IV pelvic endometriosis: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 26(1):53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2018.07.021 Epub 2018 Aug 6. PMID: 30092363

Mircea O, Puscasiu L, Resch B, Lucas J, Collinet P, von Theobald P et al (2016) Fertility outcomes after ablation using plasma energy versus cystectomy in infertile women with ovarian endometrioma: a multicentric comparative study. JJ Minim Invasive Gynecol 23(7):1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2016.08.818 Epub 2016 Aug 20. PMID: 27553184

Hogg S, Vyas S (2018) Endometriosis update. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med 28(3):61–69

Opøien HK, Fedorcsak P, Åbyholm T, Tanbo T (2011) Complete surgical removal of minimal and mild endometriosis improves outcome of subsequent IVF/ICSI treatment. Reprod Biomed Online 23(3):389–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.06.002 Epub 2011 Jun 15. PMID: 21764382

Bianchi PHM, Pereira RMA, Zanatta A, Alegretti JR, Motta ELA, Serafini PC (2009) Extensive excision of deep infiltrative endometriosis before in vitro fertilization significantly improves pregnancy rates. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 16(2):174–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2008.12.009 Erratum in: J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(5):663. PMID: 19249705

Papaleo E, Ottolina J, Viganò P, Brigante C, Marsiglio E, De Michele F et al (2011) Deep pelvic endometriosis negatively affects ovarian reserve and the number of oocytes retrieved for in vitro fertilization: pelvic endometriosis and ovarian reserve. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 90(8):878–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01161.x Epub 2011 Jun 14. PMID: 21542809

Centini G, Afors K, Murtada R, Argay IM, Lazzeri L, Akladios CY et al (2016) Impact of laparoscopic surgical management of deep endometriosis on pregnancy rate. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 23(1):113–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2015.09.015 Epub 2015 Sep 30. PMID: 26427703

Bendifallah S, Roman H, Mathieu d’Argent E, Touleimat S, Cohen J, Darai E et al (2017) Colorectal endometriosis-associated infertility: should surgery precede ART? Fertil Steril 108(3):525–531.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.002 Epub 2017 Aug 12. PMID: 28807397

Benschop L, Farquhar C, van der Poel N, Heineman MJ (2010) Interventions for women with endometrioma prior to assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11):CD008571. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008571.pub2 PMID: 21069706

Liang Y, Yang X, Lan Y, Lei L, Li Y, Wang S (2019) Effect of Endometrioma cystectomy on cytokines of follicular fluid and IVF outcomes. J Ovarian Res 12(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-019-0572-7 PMID: 31639028; PMCID: PMC6802315

Maignien C, Santulli P, Bourdon M, Korb D, Marcellin L, Lamau M-C et al (2020) Deep infiltrating endometriosis: a previous history of surgery for endometriosis may negatively affect assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Reprod Sci 27(2):545–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-019-00052-1 Epub 2020 Jan 6. PMID: 32046438

Kuroda K, Ikemoto Y, Ochiai A, Ozaki R, Matsumura Y, Nojiri S et al (2019) Combination treatment of preoperative embryo cryopreservation and endoscopic surgery (surgery-ART hybrid therapy) in infertile women with diminished ovarian reserve and uterine myomas or ovarian endometriomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 26(7):1369–1375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.02.008 Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30794888

Werbrouck E, Spiessens C, Meuleman C, D’Hooghe T (2006) No difference in cycle pregnancy rate and in cumulative live-birth rate between women with surgically treated minimal to mild endometriosis and women with unexplained infertility after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril 86(3):566–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.044 PMID: 16952506

Benaglia L, Somigliana E, Santi G, Scarduelli C, Ragni G, Fedele L (2011) IVF and endometriosis-related symptom progression: insights from a prospective study. Hum Reprod 26(9):2368–2372. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der208 Epub 2011 Jun 29. PMID: 21715451

Nuojua-Huttunen S (1999) Intrauterine insemination treatment in subfertility: an analysis of factors affecting outcome. Hum Reprod 14(3):698–703. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/14.3.698 PMID: 10221698

Hughes EG (1997) The effectiveness of ovulation induction and intrauterine insemination in the treatment of persistent infertility: a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 12(9):1865–1872. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/12.9.1865 PMID: 9363697

Keresztúri A, Kozinszky Z, Daru J, Pásztor N, Sikovanyecz J, Zádori J et al (2015) Pregnancy rate after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination for the treatment of endometriosis following surgery. Biomed Res Int 2015:282301. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/282301 Epub 2015 Jul 12. PMID: 26247014; PMCID: PMC4515270

Tummon IS, Asher LJ, Martin JSB, Tulandi T (1997) Randomized controlled trial of superovulation and insemination for infertility associated with minimal or mild endometriosis. Fertil Steril 68(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81467-7 PMID: 9207576

Guzick DS, Carson SA, Coutifaris C, Overstreet JW, Factor-Litvak P, Steinkampf MP et al (1999) Efficacy of superovulation and intrauterine insemination in the treatment of infertility. N Engl J Med 340(3):177–183. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199901213400302 PMID: 9895397

van der Houwen LEE, Schreurs AMF, Schats R, Heymans MW, Lambalk CB, Hompes PGA et al (2014) Efficacy and safety of intrauterine insemination in patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online 28(5):590–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.01.005 Epub 2014 Jan 27. PMID: 24656562

Senapati S, Sammel MD, Morse C, Barnhart KT (2016) Impact of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization outcomes: an evaluation of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies Database. Fertil Steril 106(1):164–171.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.037 Epub 2016 Apr 7. PMID: 27060727; PMCID: PMC5173290

González-Comadran M, Schwarze JE, Zegers-Hochschild F, Souza MDCB, Carreras R, Checa MÁ (2017) The impact of endometriosis on the outcome of Assisted Reproductive Technology. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 15(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-016-0217-2 PMID: 28118836; PMCID: PMC5260022

Barbosa MAP, Teixeira DM, Navarro PAAS, Ferriani RA, Nastri CO, Martins WP (2014) Impact of endometriosis and its staging on assisted reproduction outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis: impact of endometriosis on assisted reproduction outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 44(3):261–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13366 Epub 2014 Aug 13. PMID: 24639087

Pabuccu R, Onalan G, Kaya C (2007) GnRH agonist and antagonist protocols for stage I–II endometriosis and endometrioma in in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. Fertil Steril 88(4):832–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.046 Epub 2007 Apr 10. PMID: 17428479

Kolanska K, Cohen J, Bendifallah S, Selleret L, Antoine J-M, Chabbert-Buffet N et al (2017) Pregnancy outcomes after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women with endometriosis-associated infertility: GnRH-agonist versus GnRH-antagonist. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 46(9):681–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.09.007 Epub 2017 Sep 29. PMID: 28970135

Zhao F, Lan Y, Chen T, Xin Z, Liang Y, Li Y et al (2020) Live birth rate comparison of three controlled ovarian stimulation protocols for in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer in patients with diminished ovarian reserve after endometrioma cystectomy: a retrospective study. J Ovarian Res 13(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-020-00622-x PMID: 32113477; PMCID: PMC7049193

Drakopoulos P, Rosetti J, Pluchino N, Blockeel C, Santos-Ribeiro S, de Brucker M et al (2018) Does the type of GnRH analogue used, affect live birth rates in women with endometriosis undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment, according to the rAFS stage? Gynecol Endocrinol 34(10):884–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2018.1460346 Epub 2018 Apr 12. PMID: 29648476

Bourdon M, Santulli P, de Ziegler D, Gayet V, Maignien C, Marcellin L et al (2017) Does GnRH agonist triggering control painful symptom scores during assisted reproductive technology? A retrospective study. Reprod Sci 24(9):1325–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719116687659 Epub 2017 Jan 5. PMID: 28056703

Boucret L, Bouet P-E, Riou J, Legendre G, Delbos L, Hachem HE et al (2020) Endometriosis lowers the cumulative live birth rates in IVF by decreasing the number of embryos but not their quality. J Clin Med 9(8):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082478 PMID: 32752267; PMCID: PMC7464781

Niu Z, Chen Q, Sun Y, Feng Y (2013) Long-term pituitary downregulation before frozen embryo transfer could improve pregnancy outcomes in women with adenomyosis. Gynecol Endocrinol 29(12):1026–1030. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2013.824960 Epub 2013 Sep 5. PMID: 24006906

Komsky-Elbaz A, Raziel A, Friedler S, Strassburger D, Kasterstein E, Komarovsky D et al (2013) Conventional IVF versus ICSI in sibling oocytes from couples with endometriosis and normozoospermic semen. J Assist Reprod Genet 30(2):251–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-012-9922-8 Epub 2012 Dec 28. PMID: 23271211; PMCID: PMC3585678

Wu J, Yang X, Huang J, Kuang Y, Wang Y (2019) Fertility and neonatal outcomes of freeze-all vs. fresh embryo transfer in women with advanced endometriosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10:770. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00770 PMID: 31787933; PMCID: PMC6856047

Yilmaz N, Ceran MU, Ugurlu EN, Gulerman HC, Ustun YE (2021) Impact of endometrioma and bilaterality on IVF / ICSI cycles in patients with endometriosis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 50(3):101839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101839 Epub 2020 Jun 30. PMID: 32619727

Santulli P, Bourdon M, Presse M, Gayet V, Marcellin L, Prunet C et al (2016) Endometriosis-related infertility: assisted reproductive technology has no adverse impact on pain or quality-of-life scores. Fertil Steril 105(4):978–987.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.006 Epub 2015 Dec 30. PMID: 26746132

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2012) Endometriosis and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 98(3):591–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.031 Epub 2012 Jun 15. PMID: 22704630

Kuznetsov L, Dworzynski K, Davies M, Overton C, Guideline Committee (2017) Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 358:j3935. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3935 Erratum in: BMJ. 2017;358:j4227. PMID: 28877898

Cobo A, Giles J, Paolelli S, Pellicer A, Remohí J, García-Velasco JA (2020) Oocyte vitrification for fertility preservation in women with endometriosis: an observational study. Fertil Steril 113(4):836–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.017 Epub 2020 Mar 4. PMID: 32145929

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgments.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RV and AS both collected and reviewed the literature related to endometriosis and endometriosis-related infertility and wrote the scoping review. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable as it is a scoping review of the recent literature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No financial and non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vatsa, R., Sethi, A. Impact of endometriosis on female fertility and the management options for endometriosis-related infertility in reproductive age women: a scoping review with recent evidences. Middle East Fertil Soc J 26, 36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43043-021-00082-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43043-021-00082-3