Abstract

Purpose

The association of diabetes mellitus with knee stiffness after total knee arthroplasty is still being debated. The aim of this study was to assess through meta-analysis the impact of diabetes mellitus on the prevalence of postoperative knee stiffness after total knee arthroplasty.

Methods

We conducted a literature search for terms regarding postoperative knee stiffness and diabetes mellitus on Embase, CINAHL, and PubMed NCBI.

Results

Of 1142 articles, seven were suitable for analysis. Meta-analysis showed that diabetes mellitus does not confer an increased risk of primary or revision total knee arthroplasty-induced postoperative knee stiffness when compared to nondiabetic patients (primary total knee arthroplasty, estimated odds ratio [OR] 1.474 and 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.97–2.23; primary and revision total knee arthroplasty, OR 1.340 and 95% CI 0.97–1.83).

Conclusion

There is no strong evidence that diabetes mellitus increases the risk of knee stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. The decision to proceed with total knee arthroplasty, discussion as part of the consent process, and subsequent rehabilitation should not differ between patients with and without diabetes mellitus with regards to risk of stiffness.

Level of evidence

Level III (meta-analysis)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aim of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is to provide the patient with a stable, pain-free knee with a functional range of movement (ROM) that allows activities such as walking, standing from a chair, and ascending and descending stairs. To achieve this, it is estimated that up to 105° of knee flexion is required [1].

Postoperative knee stiffness is a significant, disabling complication of TKA resulting in a reduction of ROM, which significantly reduces the patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and their quality of life (QoL) [2]. ROM is also an important postoperative factor affecting patient satisfaction [3].

The incidence of knee stiffness after TKA varies from 1.3 to 12% [4,5,6]. This large variation can be explained by the lack of uniform definition of stiffness in the literature: flexion less than 90° at 2 weeks [6] and 1 year after TKA [4]; flexion less than 85° [7] and less than 110° ROM at 6 weeks after TKA [8]. Stiffness after TKA can be limited by active physiotherapy but may also require manipulation under anesthesia (MUA), which increases the risk of revision surgery.

Many risk factors may contribute to knee stiffness after TKA: reduced preoperative ROM, prosthesis malpositioning, imbalance of flexion/extension gaps, noncompliance with postoperative rehabilitation, socioeconomic status, race, gender, and diabetes mellitus (DM) [5, 6, 8, 9]. In particular, Scranton reported that 85% of TKA patients with stiff knee had DM [7].

DM currently has a prevalence of over 422 million worldwide [10]. The prevalence of DM in patients undergoing TKA is 12.2%, and with an increasingly elderly population, the incidence of DM as well as osteoarthritis (OA) is increasing [11]. Patients with DM are considered to have greater overall complications and higher revision rates after TKA [12]. One in three patients with frozen shoulder has DM and 13% of diabetic patients develop frozen shoulder [13]. It is unclear if DM affects all joints equally or whether it affects certain joints more commonly.

The purpose of this meta-analysis is to establish the risk of postoperative knee stiffness in diabetic patients after TKA from the current published literature in order to provide surgeons with an evidence base for guiding them as to the likelihood of suffering postoperative stiffness. Increasing current knowledge on the prevalence of postoperative knee stiffness may also help to set realistic goals of postoperative ROM and allow more rigorous physiotherapy to reduce the risk of joint stiffness. We hypothesize that DM increases the risk of postoperative knee stiffness after TKA.

Methods

A literature search was conducted on October 31st, 2018 using Embase, CINAHL, and Pubmed NCBI (National Centre of Biotechnology Information). The search terms used were ‘knee AND arthrofibrosis AND diabetes’, ‘knee AND stiff AND diabetes’, and ‘knee AND stiffness AND diabetes’. No restrictions were applied to the date of publication or language. Ethical approval was not required. The study was conducted and meets the ethical standards as per the recommendations by Padulo et al. [14].

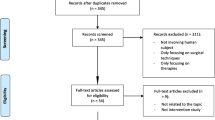

The search returned 1142 articles. The titles and abstracts of these articles were reviewed. Studies were included if they identified the prevalence of knee stiffness after TKA in a diabetic population. Case reports, series, duplicated articles, and reviews were also excluded. The studies had to define what they considered as knee stiffness. Essentially studies included compared stiffness in diabetic and nondiabetic patients after TKA. Studies including primary and revision TKA were included. When performing our analysis, we looked at the number of TKAs performed rather than the number of patients. The Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) assessment was used to assess included studies for bias [15].

Statistical analysis

A random-effects model was used to perform meta-analysis. Confidence intervals (95%) and summary odds ratios (OR) were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed using tau2, I2, Q, and P values. The data were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA).

Results

Our initial search identified 1142 articles (Fig. 1). Seven studies were included for analysis [4, 8, 12, 16,17,18,19](Table 1). Patients in these studies with and without DM were treated similarly with regard to postoperative physiotherapy. Six studies presented data on primary TKA. One study included revision TKA patients [19].

In one study [8], the CI reported did not correspond correctly to the OR given. The authors were contacted for clarification, but as this was not obtained, the reported OR and lower limit of CI along with a recalculated upper limit CI were utilized in the meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis showed that DM does not confer a higher risk of stiffness after TKA (for primary and revision TKAs combined, OR 1.340, 95% CI 0.97–1.83; for heterogeneity, tau2 = 0.086, I2 = 63.9, Q-value = 16.630, and P value = 0.068; Fig. 2). Funnel plot visual inspection analysis did not show an obvious small study effect (Fig. 3).

Analysis of only primary TKAs with revision TKAs excluded also demonstrates that DM does not significantly increase the risk of stiffness after primary TKA (OR 1.474, 95% CI 0.97–2.23; heterogeneity, tau2 = 0.143, I2 = 69.689, Q-value = 16.496, and P value = 0.066; Fig. 4).

The MINORS [15] assessment for bias showed a low score (18–22; Table 2).

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows that there is no strong evidence that diabetic patients are at an increased risk of postoperative knee stiffness compared to non-diabetic patients after TKA. Our findings suggest that fear of postoperative knee stiffness should not influence the decision to undertake TKA in diabetic patients and that diabetic patients need not be managed differently from non-diabetic patients in the postoperative period.

Diabetes is known to be associated with reduced joint mobility and adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder [13]. Studies have assessed the mechanisms underlying tissue fibrosis in DM. Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly in obese patients [20], such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and 1B (IL-1B) [20] result in the deposition of extracellular matrix and fibrosis [21]. Recent studies also show evidence of pro-inflammatory cytokine production from Toll-like receptor 4-driven responses resulting in synovial hyperplasia, macrophage activation, cartilage catabolism, and joint destruction [22].

A range of glycated, oxidized, and nitrated proteins have been detected in the synovial fluid of patients with knee OA [23]. The formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) is increased in diabetes and leads to increased crosslinking and stiffness of collagen with altered tissue function and biomechanics [24]. Increased methylglyoxal has been found specifically in the synovial fluid of diabetic compared to nondiabetic patients with OA [25]. A recent experimental study has shown that AGE increases collagen I and III gene expression only with immobilization, which is relevant to TKA [26].

Myofibroblast and growth factor numbers are known to be increased in stiff joints, including adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder and stiff elbows requiring surgical release [27]. Activation of the myofibroblast–mast cell–neuropeptide pathway in response to injury may also contribute to joint stiffness following TKA, by linking acute inflammation with subsequent contracture [28, 29]. Diabetes mellitus is known to cause crosslinking of collagen due to the formation of AGEs [24]. A recent study has shown increased expression of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including high-mobility group box-1, the receptor for advanced glycation end products, and alarmins (S100A8 and S100A9) in the knee compared to the hip joint [30]. This is thought to facilitate increased cartilage degradation and inflammation.

From the existing literature, DM clearly has an impact on the inflammatory process, which can result in fibrosis and stiff joints, particularly in the shoulder and elbow. Results in the literature differ regarding the impact of DM on knee stiffness. This meta-analysis has shown no difference between the rate of stiffness after TKA in diabetic and nondiabetic patients. DM results in systematic inflammation and therefore it would be expected to affect all joints to a similar extent. There must be a reason as to why different joints appear to have differing susceptibilities to stiffness induced by DM. Evidence in the literature is currently inadequate to explain this variation. We postulate it may be due to different joints expressing different levels of receptors to inflammatory cells involved in the DM inflammatory cascade as described previously. The difference in structure between different joints and their frequency of use in typical daily life may also affect the risk of developing stiffness in a particular joint. Further work is needed to investigate this important difference to enhance our knowledge of the pathological process and help to provide strategies to combat joint stiffness.

A limitation of this study is that the meta-analysis included only seven studies. This highlights the limited evidence in the current literature regarding the effect of DM on postoperative knee stiffness after TKA, especially revision TKA. On the basis of the evidence currently available, our results suggest that patients with diabetes are not at an increased risk of postoperative knee stiffness compared to nondiabetic patients after TKA. The studies included in the meta-analysis reported differing results, which demonstrates the value of performing this meta-analysis in order to clarify the overall picture of results in the literature. These studies varied in their definitions of knee stiffness, and the studies included either the need for MUA or a ROM less than 90°. Most of the studies were not prospective or randomized, potentially affecting sampling bias, although they scored low on bias assessment. None of the studies stated they managed DM and non-DM patients differently, which could have affected results if, for example, more intensive physiotherapy was given to the DM patients, reducing their risk of developing stiffness. With reviews of large databases there is also the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate data. Several studies were excluded from the meta-analysis as they included both painful and stiff knees postoperatively. The majority of studies did not specify whether they included patients with type 1 diabetes, although given that the majority of patients with OA will be elderly, it is likely that they had type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the relation between diabetes control and risk of stiffness cannot be determined.

Conclusion

DM does not confer a higher risk of knee stiffness after TKA. We recommend that the decision to proceed with TKA, discussion as part of the consent process, and subsequent rehabilitation should not differ between patients with and without DM with regards to risk of stiffness.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- AGEs:

-

Advanced glycation end-products

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- DAMPs:

-

Damage-associated molecular patterns

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica dataBASE

- IL:

-

Interleukin 6

- MINORS:

-

Methodological Index for NonRandomized Studies

- MUA:

-

Manipulation under anaesthesia

- NCBI:

-

National Centre of Biotechnology Information

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- ROM:

-

Range Of movement

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- TNF-α:

-

Tumour necrosis factor alpha

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

References

Laubenthal KN, Smidt GL, Kettelkamp DB (1972) A quantitative analysis of knee motion during activities of daily living. Phys Ther 52(1):34–43

Padua R, Ceccarelli E, Bondi R, Campi A, Padua L (2007) Range of motion correlates with patient perception of TKA outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 460:174–177

Schurman DJ, Parker JN, Ornstein D (1985) Total condylar knee replacement. A study of factors influencing range of motion as late as two years after arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 67(7):1006–1014

Gandhi R, de Beer J, Leone J, Petruccelli D, Winemaker M, Adili A (2006) Predictive risk factors for stiff knees in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 21(1):46–52

Daluga D, Lombardi AV Jr, Mallory TH, Vaughn BK (1991) Knee manipulation following total knee arthroplasty. Analysis of prognostic variables. J Arthroplast 6(2):119–128

Fisher DA, Dierckman B, Watts MR, Davis K (2007) Looks good but feels bad: factors that contribute to poor results after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 22(6 Suppl 2):39–42

Scranton PE Jr (2001) Management of knee pain and stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 16(4):428–435

Issa K, Rifai A, Boylan MR, Pourtaheri S, McInerney VK, Mont MA (2015) Do various factors affect the frequency of manipulation under anesthesia after primary total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 473(1):143–147

Parsley BS, Engh GA, Dwyer KA (1992) Preoperative flexion. Does it influence postoperative flexion after posterior-cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 275:204–210

WHO fact sheet on diabetes. https://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/WHD2016_Diabetes_Infographic_v2.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2018

Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE (2014) Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103(2):137–149

Meding JB, Reddleman K, Keating ME, Klay A, Ritter MA, Faris PM et al (2003) Total knee replacement in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 416:208–216

Zreik NH, Malik RA, Charalambous CP (2016) Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder and diabetes: a meta-analysis of prevalence. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 6(1):26–34

Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N (2013) Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 3(4):250–252

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J (2003) Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 73(9):712–716

Pfefferle KJ, Shemory ST, Dilisio MF, Fening SD, Gradisar IM (2014) Risk factors for manipulation after total knee arthroplasty: a pooled electronic health record database study. J Arthroplast 29(10):2036–2038

Clement ND, Bardgett M, Weir D, Holland J, Deehan DJ. Increased symptoms of stiffness 1 year after total knee arthroplasty are associated with a worse functional outcome and lower rate of patient satisfaction. Knee Surg, Sports Traumatology, Arthrosc. 2019;27(4):1196–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-4979-2

Cartwright-Terry M, Cohen DR, Polydoros F, Davidson JS, Santini AJ (2018) Manipulation under anaesthetic following total knee arthroplasty: Predicting stiffness and outcome. J Orthop Surg 26(3):2309499018802971

Dowdle SB, Bedard NA, Owens JM, Gao Y, Callaghan JJ (2018) Identifying risk factors for the development of stiffness after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 33(4):1186–1188

Welty FK, Alfaddagh A, Elajami TK (2016) Targeting inflammation in metabolic syndrome. Transl Res 167(1):257–280

Zeisberg M, Kalluri R (2013) Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 1. Common and organ-specific mechanisms associated with tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304(3):C216–C225

Kalaitzoglou E, Griffin TM, Humphrey MB (2017) Innate immune responses and osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 19(8):45

Ahmed U, Anwar A, Savage RS, Thornalley PJ, Rabbani N (2016) Protein oxidation, nitration and glycation biomarkers for early-stage diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the knee and typing and progression of arthritic disease. Arthritis Res Ther 18(1):250

Friedman EA (1999) Advanced glycosylated end products and hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Diabetes Care Suppl 2:B65–B71

Zhang W, Randell EW, Sun G, Likhodii S, Liu M, Furey A et al (2017) Hyperglycemia-related advanced glycation end-products is associated with the altered phosphatidylcholine metabolism in osteoarthritis patients with diabetes. PLoS One 12(9):e0184105

Ozawa J, Kaneguchi A, Minamimoto K, Tanaka R, Kito N, Moriyama H. Accumulation of advanced-glycation end products (AGEs) accelerates arthrogenic joint contracture in immobilized rat knee. J Orthop Res 2018;36(3):854–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23719.

Bunker TD, Anthony PP (1995) The pathology of frozen shoulder. A Dupuytren-like disease. J Bone Joint Surg 77(5):677–683

Hildebrand KA, Zhang M, Salo PT, Hart DA (2008) Joint capsule mast cells and neuropeptides are increased within four weeks of injury and remain elevated in chronic stages of posttraumatic contractures. J Orthop Res 26(10):1313–1319

Charalambous CP, Morrey BF (2012) Posttraumatic elbow stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(15):1428–1437

Rosenberg JH, Rai V, Dilisio MF, Sekundiak TD, Agrawal DK (2017) Increased expression of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in osteoarthritis of human knee joint compared to hip joint. Mol Cell Biochem 436(1–2):59–69

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved equally in all aspects of the creation of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jump, C., Malik, R.A., Anand, A. et al. Diabetes mellitus does not increase the risk of knee stiffness after total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of 7 studies including 246 053 cases. Knee Surg & Relat Res 31, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43019-019-0004-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43019-019-0004-4