Abstract

This paper is centered on a numerical solution of non-Newtonian Casson magneto-nanofluid flow underlying an axisymmetric surface through a non-Darcian porous medium with heat generation/absorption. Using similarity transformations, the system of PDEs with the corresponding boundary conditions are reduced to system of nonlinear ODEs. The Chebyshev pseudospectral (CPS) method is used to get a numerical solution for the formulated differential system. Comparisons of the present numerical results with previously published results are made, and fine agreements for some the considered values of parameters were noted. Two cases of nanofluid are considered. The first case is Newtonian nanofluid, water with suspended gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles, and representative results are obtained for β → ∞ and Pr = 6.785 (the Prandtl number of water). The second case is non-Newtonian bio-nanofluid, blood with suspended gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles, and representative results are obtained for β = 0.1 and Pr = 25 (the Prandtl number of blood). The variation of different physical parameters on non-dimensional velocity and temperature fields as well as the skin friction coefficient and the Nusselt number are discussed. It is demonstrated that the implication of a nanoparticle into bio-fluid can modify the stream design. Also, the nanoparticles with high thermal conductivity (gold) have better enhancement on heat transfer compared to alumina, i.e., the effectiveness of adding gold to the water and blood is higher than adding alumina. One of the most important applications of nanotechnology in the field of medicine is the use of nanoparticles (gold molecules) in chemotherapy to get rid of cancer cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluid with suspended (nanometer-sized particles) nanoparticles is called nanofluid. The first proposition in this area was through Choi’s seminal work at Argonne National Laboratory [1]. The nanoparticles applied in nanofluids are ordinarily made of metals (Al, Cu), oxides (Al2O), nitrides (AlN, SiN), carbides (SiC), or nonmetals (carbon nanotubes, graphite). Also, the biologists have been utilizing diverse kinds of particles, for example, DNA, RNA, proteins, or fluids contained in nanopores [2,3,4]. The base fluid is commonly a conductive fluid, such as water or ethylene glycol. Other base fluids are oil and other lubricants, bio-fluids, and polymer solutions. Nanofluids portray heat transfer fluids that display thermal properties better than those of their host fluids. In this way, the utilization of nanofluids, for example, in heat exchangers, may result in energy and cost reserve funds and ought to encourage the direction of device miniaturization. Additionally, the investigation of particulate suspensions has astounding applications which incorporates high power X-rays, optical devices, biomedical science, material synthesis, and lasers. As of late utilization of nanotechnology in biomedical engineering and medicine has created a lot of interest in thermal properties of bio-nanofluid such as blood with nanoparticle suspension. Among the applications of nanotechnology in the field of medicine currently under development is the use of nanoparticles for the delivery of drugs, heat, light, and other substances to certain types of cells (such as cancer cells). Also, there are nanoparticles, gold, that provide chemotherapy drugs directly to the cancer cells without reaching healthy cells and are still in the development stage and final tests for final approval for use with cancer patients.

In latest couple of decades, scientists and researchers around the world endeavored to continually deal with different parts of nanotechnology. Ghassemi et al. [5] investigated a new effective thermal conductivity model for a bio-nanofluid (blood with nanoparticle Al2O3). Chamkha and Aly [6] studied MHD-free convection flow of a nanofluid past a vertical plate in the presence of heat generation or absorption effects. Natural convective boundary layer flow over a horizontal plate embedded in a porous medium saturated with a nanofluid was reported by Gorla and Chamkha [7]. Also, a numerical study for forced convection flow of nanofluid through a porous medium using Brinkman–Forchheimer model was analyzed by Khan and Pop [8]. Ashorynejad et al. [9] presented a nanofluid flow and heat transfer due to a stretching cylinder in the presence of magnetic field. Shooting method and Chebyshev spectral collocation techniques are used to compute magnetic parameter effects on slip magnetic nanofluid flows from both stretching and shrinking sheet flows by Uddin et al. [10]. Khan et al. [11] analyzed a model for a three-dimensional nanofluid flow. Ferdows et al. [12] employed an explicit finite difference method to investigate combined thermal radiation and transverse magnetic field effects on unsteady magneto-convection from an extending nanopolymer sheet with wall mass flux effects. Sreedevi et al. [13] and Prabhavathi et al. [14] scrutinized MHD boundary layer heat and mass transfer flow over a vertical cone embedded in a porous media filled with nanofluid. A numerical simulation for melting heat transfer and radiation effects in stagnation point flow of carbon-water nanofluid was studied by Hayat et al. [15]. More recently, Zeeshan et al. [16] inspected an analysis of activation energy in Couette-Poiseuille flow of nanofluid in the presence of chemical reaction and convective boundary conditions. Analysis of magneto-hydrodynamics heat and mass transfer analysis of single and multi-wall carbon nanotubes over vertical cone with convective boundary condition was analyzed by Sreedevi et al. [17]. Also an analysis of heat and mass transfer enhancement in mixed convection in a Brinkman–Darcy flow of Au-water and Ag-water nanofluids was reported by Mendu et al. [18]. Furthermore, in the last few years, several studies for convection nanofluid flow through a pour medium have been done [19,20,21,22,23].

Copious studies show the significance of non-Newtonian attributes of numerous liquid materials, both in nature and in technology. An accumulation of non-Newtonian models have been delivered in the latest years, as a declaration of the rheological properties of various liquids. In addition, most of the physiological liquids in the human body act like a non-Newtonian fluid. Blood is a suspension of red platelets (erythrocytes), white platelets (leukocytes), and platelets in a mind-boggling arrangement (plasma) of gases, proteins, salts, sugars, and lipids, i.e., in corpuscles (a little platelet), blood being suspended, and at little shear rates, acts like non-Newtonian liquid in minor veins. Consequently, it is conventionally to think about that blood is a non-Newtonian liquid involving platelets and blood plasma.

A lot of authors investigated the particle motion in different biological fluids for describing rheological behavior of blood. For example, the stopping/starting flow of fluid through a pipe without/with stenosis was investigated by Nakamura and Sawada [24]. Wang [25, 26] presented theoretical and approximate solutions for a fluid flow and heat transfer analysis underlying spreading surface, respectively. Also, Lin and Chen [27] have given exact solution for the heat transfer analysis of Wang’s problem [25, 26]. Furthermore, the problem of MHD flow of non-Newtonian fluid through porous medium underlying spreading surface was scrutinized by Eldabe et al. [28]. Seddeek and Salem [29] studied effectiveness of both variable viscosity and thermal diffusivity on the fluid flow underlying spreading surface. Lately, Elgazery [30] analyzed numerically the effectiveness of variable properties on flow and heat transfer about a biviscosity fluid through a porous medium.

In most of the abovementioned studies, the spreading of non-Newtonian fluid with suspension of nanoparticles as through tissues and porous membranes in human body is not taken into account. So, the objective of the current study extend the recent work of Elgazery [30] to analyze the effect of internal heat generation/absorption on a non-Newtonian Casson fluid with suspension of gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles, flow underlying spreading surface through a non-Darcian porous medium. Two cases of nanofluid are considered. The first is Newtonian nanofluid, water with β → ∞ and Pr = 6.785. The second is non-Newtonian bio-nanofluid, blood with β = 0.1 and Pr = 25. The governing equations are reduced to ODEs by appropriate similarity transformation before solving numerically by using the Chebyshev pseudospectral technique. Therefore, this study gives a more exact picture of flow and heat transfer in this issue than the standard investigation with regular fluid. The effectiveness of utilizing nanoparticles on this motion appeared in tables and graphs.

Formulation of the problem

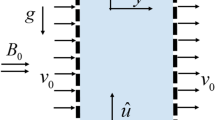

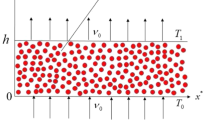

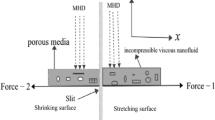

Consider a steady laminar boundary layer flow and heat transfer for a non-Newtonian Casson nanofluid containing different type of nanoparticles gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) in the presence of internal heat generation/absorption. The flow model is shown in Fig. 1 and consists of a flow of a viscous, incompressible electrically conducting nanofluid that occupies the space for z ≥ 0, lying in the plane z = 0, and spreading underlying a film (membrane) of thickness h. It assumed that a non-uniform vertical magnetic field B(r) = B0/r as a function of radial distance r is applied to the flow. Also, it assumed that the nanofluid saturated non-Darcy porous medium with non-uniform permeability K(r) as a function of radial distance r. Transport underlying the membrane takes place when a driving force is applied to the nanofluid; this driving force is a temperature difference ΔT across the boundary layer [31]. The pressure gradient which is built up by the solid structure in the porous medium is neglected. It assumed that the base fluid and the nanoparticles are in thermal equilibrium and no slip occurs between them. The thermophysical properties of the nanofluids are given in Table 1 [32].

The governing boundary layer equations for this investigation are based on the balance laws of mass, linear momentum, and energy equation. Under these assumptions, and according to the boundary layer approximation with axisymmetric cylindrical polar coordinate system (r, φ, z), the flow is assumed to be axisymmetric. Hence, the velocity components and the temperature are independent of φ. The rheological model of state for an isotropic and incompressible flow of a non-Newtonian Casson fluid is defined as follows [33, 34]:

where τij is the stress tensor, μnf is the effective plastic dynamic viscosity of the nanofluid (see Eq. 10), and py is the yield stress of the nanofluid. π0 = eijeij and πc is a critical value of this product, where \( {\mathrm{e}}_{ij}=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{i}}}{\partial {\mathrm{x}}_{\mathrm{j}}}+\frac{\partial {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{j}}}{\partial {\mathrm{x}}_{\mathrm{i}}}\right) \) is the deformation rate.

Few examples of Casson fluids are jelly, tomato sauce, honey, concentrated fruit juice, and blood. Moreover, the Casson model is sometimes stated to fit rheological data better than general viscoelastic model for many materials [33, 34].

The governing steady boundary layer equations governing the flow and heat transfer for non-Newtonian Casson nanofluid in the presence of internal heat generation source/absorption sink are described by the following equations [25, 26, 28, 29]:

where

The appropriate boundary conditions are [27]

where u and w are the fluid velocity components in r and z directions, respectively. T is the fluid temperature, c is the inertia coefficient, and Q0 is the heat generation/absorption coefficient. T∞ is the temperature of the fluid far away from the surface. Tw(r) is the temperature of the plate which can be defined as Tw(r) = T∞ + Arn [28], where A is empirical constant. n is the surface temperature variation parameter. Also, F = Q/(2π h) is a constant, h is the thickness of spreading film, and Q is the volume flux on the surface at z = 0. Furthermore, ρnf is the effective density of the nanofluid, (ρ cp)nf is the heat capacitance of the nanofluid, and αnf is the effective thermal diffusivity of the nanofluid, which defined as [32, 35]:

Also, the following model is used for determining the electrical conductivity of nanofluids σnf [36, 37]:

Eq. (7a) can take the following form:

where D1, D2, and D3 are constant given by:

Moreover, μnf given by Brinkman [38] as:

where φ is the solid volume fraction of the nanoparticles, ρf is the reference density of the fluid, ρs is the reference density of the solid, CP is the specific heat at constant pressure, knf is the effective thermal conductivity of the nanofluid, kf is the thermal conductivity of the fluid, ks is the thermal conductivity of the solid, σf is the electrical conductivity of the fluid, σs is the electrical conductivity of the solid, and μf is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid. Using the following similarity transformations [33, 34]:

where f(η) and θ(η) are the stream and temperature functions, respectively. νf = μf/ρf is the kinematic viscosity of the nanofluid.

The requirement of continuity Eq. (2) is automatically satisfied and by substituting Eqs. (8, 9, 10, and 11) into Eqs. (3, 4, 5, and 6) becomes

where the primes denote differentiation with respect to η. \( \beta ={\mu}_f\sqrt{2\;{\pi}_c}/{p}_y \) is the upper limit apparent viscosity coefficient parameter (for Newtonian fluid β → ∞). \( \Pr =\frac{\nu_f\;}{\alpha_f} \) is the Prandtl number, and \( q=\frac{Q_0\;}{{\left(\rho\;{c}_p\right)}_f}\frac{r^2}{F} \) is the heat source (q > 0) or sink (q < 0). γ = c r, \( Da=\frac{F\;K(r)}{\nu_f\;{r}^2} \), and \( M=\frac{\sigma_{\mathrm{nf}}}{\rho_{\mathrm{nf}}}\frac{B_0^2}{F} \) are porous medium inertia coefficient, permeability, and magnetic parameters, respectively.

It should be observed that for a regular fluid (φ = 0) and absence of heat generation/absorption (q = 0), Eqs. 12 and 13 reduce to Eqs. 10 and 11 from Elgazery [30] in non-variable viscosity, non-variable thermal conductivity, non-magnetic field, and absence of concentration case.

The physical amounts of enthusiasm for this issue are the local skin friction which identified with f ’’ (0) by the relation \( Cf={\tau}_w{\left[{\rho}_{\mathrm{nf}}{\left(\frac{F}{r}\right)}^2\sqrt{\frac{\nu_f}{F}}\right]}^{-1} \) and by using Eq. (11).

where τw = (τrz)z = 0 is the shear stress at the surface.

The local heat transfer on the surface might be composed by the heat flux

and the heat transfer coefficient

Then, Nusselt number (Nu) can be gotten from the numerical outcomes by the connection

Numerical procedure

The Chebyshev polynomials are utilized broadly in numerical calculations. The Chebyshev polynomials have demonstrated effectively in the numerical arrangement of different boundary value problems [39, 40] and in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) [41,42,43]. The present study manages use of Chebyshev pseudospectral technique to deal with the boundary layer equations in MHD flow. Hence, the Chebyshev pseudospectral (CPS) method used to solve the system of two-dimensional momentum and energy ordinary differential Eqs. (12 and 13) with boundary conditions (14) (see for example [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]).

Using the algebraic mapping [53],

The domain in the η direction is [0, η∞] where η∞ is the edge of boundary layer is mapped into computational region [−1, 1] and the Eqs. (12, 13, 14a and 14b) are transformed into the following system:

The derivatives of the function f(x) at Gauss–Lobatto points \( {x}_k=\cos\;\left(\frac{k\pi}{L}\right) \) are given by [54]

f(n) = D(n)f.

where

\( \underline{f}={\left[f\left({x}_0\right),f\left({x}_1\right),\dots, f\left({x}_L\right)\right]}^T, \)

and

\( {\underline{f}}^{(n)}={\left[{f}^{(n)}\left({x}_0\right),{f}^{(n)}\left({x}_1\right),\dots, {f}^{(n)}\left({x}_L\right)\right]}^T. \)

where D(n) is the pseudospectral differentiation matrix

\( {D}^{(n)}=\left[{d}_{k,j}^{(n)}\right], \)

or \( {f}^{(n)}\left({x}_k\right)=\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(n)}f\left({x}_j\right). \)

where

\( {d}_{k,j}^{(n)}=\frac{2\;{\gamma}_j^{\ast }}{L}\sum \limits_{j=0}^L\sum \limits_{\begin{array}{l}\kern1.08em m=0\\ {}\left(m+l-n\right)\mathrm{even}\end{array}}^{l-n}\left({\gamma}_l^{\ast}\;{a}_{m,l}^n\;{\left(-1\right)}^{\left[\frac{lj}{L}\right]+\left[\frac{mk}{L}\right]}\;{x}_{lj-L\left[\frac{lj}{L}\right]}\;{x}_{mk-L\left[\frac{mk}{L}\right]}\right), \)

and

\( {a}_{m,l}^n=\frac{2^nl}{\left(n-1\right)!{c}_m}\frac{\left(s-m+n-1\right)!\left(s+n-1\right)!}{s!\left(s-m\right)!}{a}_l \),

such that 2s = l + m − n and c0 = 2, ci = 1, i ≥ 1, where k, j = 0, 1, 2, … , L and \( {\gamma}_0^{\ast }={\gamma}_l^{\ast }=\frac{1}{2}, \) \( {\gamma}_j^{\ast }=1\kern0.24em \mathrm{for}\;j=1,2,3,\dots, L-1 \) [54].

Therefore, the system of Eqs. (20, 21, and 22) are changed into the accompanying Chebyshev pseudospectral system:

\( {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\left(1+\frac{{\left(1-\varphi \right)}^{2.5}}{\beta}\right)\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(3)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)\\ {}+\left(\frac{\eta_{\infty }}{2}\right){\left(1-\varphi \right)}^{2.5}{D}_1\left[f\left({\zeta}_k\right)\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(2)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)+\left(1-\gamma \right){\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(1)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)}^2\right.\left.-M\left(\frac{\eta_{\infty }}{2}\right)\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(1)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)\right]\\ {}-{\left(\frac{\eta_{\infty }}{2}\right)}^2\left(\frac{1}{\mathrm{Da}}\right)\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(1)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)=0,\kern12.35999em k=2(1)L-1,\end{array}} \)

\( {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(2)}\theta \left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)+\frac{D_2}{D_3}\Pr \left(\frac{\eta_{\infty }}{2}\right)\left[f\left({\zeta}_k\right)\;\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(1)}\theta \left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)-n\;\theta \left({\zeta}_k\right)\;\left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{k,j}^{(1)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)\right]\\ {}+\frac{q}{D_3}{\left(\frac{\eta_{\infty }}{2}\right)}^2\theta \left({\zeta}_k\right)=0,\kern15.83999em k=1(1)L-1,\end{array}} \)

and

\( f\left(-1\right)=0,\kern0.84em \left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{0,j}^{(1)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)=\frac{\eta_{\infty }}{2},\kern0.96em \theta \left(-1\right)=1,\kern1.08em \left(\sum \limits_{j=0}^L{d}_{L,j}^{(1)}f\left({\zeta}_j\right)\right)=0\kern0.6em \mathrm{and}\kern0.6em \theta (1)=0, \)

The nonlinear system which contains 2 L-1 equations for the unknown f(ζi), i = 1(1) L, and θ(ζi), i = 1(1) L-1 is solved by the Newton method (take L = 30).

The computations have been done by using Mathematica 10.4™ software running on a PC. A comparison is made with the obtainable published data in Table 2 which demonstrate a decent concurrence with the present outcomes.

Results and discussion

The reason for the present study is to investigate a non-Newtonian Casson magneto-nanofluid flow underlying an axisymmetric spreading surface through a non-Darcian porous medium with heat generation/absorption. The system of PDEs is transformed to system of nonlinear ODEs which are investigated numerically by Chebyshev pseudospectral (CPS) method with Mathematica software.

Firstly, the values of the Chebyshev pseudospectral approximation for the Nusselt number θ ' (0) with magnetic parameter M and the surface temperature variation parameter n are compared with those from the available published data [27] and [29] in Table 2. This comparison appears a very good agreement and lends to confidence in the numerical solutions and displays that the numerical method is suitable for the solution of the present work.

The numerical solution was presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5 and graphically in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13. To ponder the conduct of these profiles, bends are drawn for different values of the parameters that portray the stream at suitable value of η∞ in two cases of nanofluid are considered. The first case is nanofluid, water with suspended gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles. The second case is bio-nanofluid, blood with suspended gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles.

Gold/alumina nanoparticles suspended in water

In this section, the representative results of nanofluid (water) with suspended gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles are obtained for β → ∞ (Newtonian fluid) and Pr = 6.785 (the Prandtl number of water).

Figure 2 shows the behavior of the velocity and temperature profiles of nanofluid (water) with two types of nanoparticles (gold and alumina). It is noticed that both momentum and thermal boundary layer thickness change with change in the type of nanoparticles. This figure displays that the momentum boundary layer thickness reduces by the addition of alumina nanoparticles and decrease further if added gold nanoparticles to the water. While the thermal boundary layer thickness increases with the addition of alumina nanoparticles and increases more if added gold nanoparticles to the water. In other words, the effectiveness of adding gold to the water is more than adding alumina. Furthermore, the temperature profile starts with the plate temperature and then decreases monotonically to zero satisfying the far field boundary condition. The influence of the heat generation/absorption on water with gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) as nanoparticles is given in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. Figure 3 indicates that as heat generation source (q > 0) increases, the temperature profile increases. From this figure, we noticed that the effect of heat generation source on temperature distribution is more pronounced in the water with gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) as nanoparticle case than in the pure water case. Also, the thickness of the thermal boundary layer for pure fluid (water) is smaller than the thermal boundary layer thickness for Al2O3-water or Au-water as presented in this figure. However, the opposite results occur with heat absorption sink (q < 0) as shown in Fig. 4. This figure displays that, as |q| increases the temperature profile decreases. The variations of the local skin friction coefficient Cf and the local Nu with two nanofluids, Au-water, and Al2O3-water for both cases of magnetic field parameter (M = 0 and M = 1) are represented in Fig. 5. The local skin friction coefficient Cf decreases with increasing φ for the gold as nanoparticles, whereas the local skin friction coefficient Cf profile takes a parabola shape with increasing φ for Alumina (Al2O3) as nanoparticles. In addition, the highest skin friction coefficient is recorded for the Alumina-water compared to the gold water. Moreover, the skin friction coefficient Cf of nanofluids without magnetic field is lower than that of magneto-nanofluids. On the other hand, as the nanoparticle volume fraction φ and magnetic field parameter M increase, the local Nusselt number decreases for gold/alumina water as shown in Fig. 5. These results are similar to those reported for the blood flow in the next section. Also, in gold water case, the magnetic field parameter M is clearer than in alumina-water case.

Table 3 denotes the numerical results of the local Nu for various n, q, and φ with Da = γ = M = 0.1. From this table, we notice that for the case of pure fluid (φ = 0) for heat generation/absorption, as the surface temperature variation n parameter increases, the heat transfer rate (Nusselt number) increases, whereas as the heat generation source (q > 0) increases, the Nusselt number decreases. On the other hand, for the case of nanofluid for heat generation/absorption, as n parameter increases, the Nusselt number increases, whereas the Nusselt number decreases with the increasing in the heat generation source’s value. Additionally, from Table 3, the Nusselt number decreases as the nanoparticle volume fraction parameter φ increases. Moreover, for nanofluid, we notice that the values of the Nusselt number for gold as nanoparticles are less than these values for alumina as nanoparticles.

Gold/alumina nanoparticles suspended in the blood

In this section, the representative results of bio-nanofluid (blood) with suspended gold (Au) or alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles are obtained for β = 0.1 (non-Newtonian fluid) and Pr = 25 (the Prandtl number of blood).

Figure 6 gives the behavior of the velocity and temperature profiles of nanofluid (blood) with two types of nanoparticles (gold and alumina). It is noticed that both momentum and thermal boundary layer thickness change with change in the type of nanoparticles. Figure 6 displays that the minimum value of the velocity is obtained by adding gold to the blood, while for pure fluid (without adding nanoparticles), the maximum value of the velocity is observed. In fact, the nanoparticles with high thermal conductivity (gold) have better enhancement on heat transfer compared to alumina, i.e., the effectiveness of adding gold to the water and blood is higher than adding alumina. Also, this figure shows that the minimum value of the temperature is obtained for pure fluid and by adding alumina or gold as nanoparticles to the blood respectively, the temperature’s curve moves to maximum value, i.e., the thermal boundary layer thickness is related to the increased thermal conductivity of the nanoparticles (see Table 1). In fact, the high value of thermal diffusivity causes a drop in the temperature gradients and accordingly increases the boundary thickness as plotted in Fig. 6. Physically, one of the most important applications of nanotechnology in the field of medicine is the use of nanoparticles (gold molecules) in chemotherapy to get rid of cancer cells. In addition, one of the main purposes of this study is to evaluate the effect of the heat generation/absorption on magneto-nanofluid spreading through porous membranes in the human body. Then, Fig. 7 represents the effect of the heat source/sink on the blood with suspension of nanoparticles. This figure indicates the response in (a) Al2O3-blood and (b) Au-blood temperature distribution across the boundary layer to various values of heat generation source (q > 0) and heat absorption sink (q < 0). It is clear from this figure that the thermal boundary layer decreases for (q < 0). Physically, the internal heat sink may be exploited to successfully cool the regime, whereas the opposite trend is spotted for heat generation source (q > 0). Moreover, in addition of alumina or gold as nanoparticles to the blood and under the influence of the heat source/sink, we will get the same effect on the temperature distribution. Figure 8 illustrates the effect of the permeability parameter Da on the velocity profile for bio-nanofluid (blood with gold or alumina nanoparticles), respectively. It depicts that the velocity distribution increases by increasing the permeability parameter Da. It is expected that an increase in the permeability of a porous membrane leads to a rise in the spreading of the blood through it. Also, we observed that the effectiveness of porous medium becomes small and vanish as Da → ∞. Physically, this outcome can be accomplished when the openings of the permeable medium are extensive, and then, the opposition of the medium might be disregarded. Figures 9 and 10 describe the effect of the porous medium inertia coefficient γ on the velocity and temperature profiles for blood with two different nanoparticles (gold and alumina), respectively. It displays that as the porous medium inertia coefficient γ increases, the velocity decreases; however, the temperature increases. Moreover, the momentum boundary layer thickness decreases whereas the thermal boundary layer thickness increases by increasing the porous medium inertia coefficient γ. Also, the effect of the porous medium inertia coefficient γ on the temperature distribution of the blood flow is less clear and can be negligible compared to its effect on the velocity distribution of the blood flow as observed in Figs. 9 and 10. Similar effects are observed from Fig. 11 as the non-Newtonian property β works to decrease the blood velocity. This implies that as β increases, the velocity decreases. Moreover, it is evident that the non-Newtonian fluid changes into Newtonian fluid as β → ∞. Additionally, the impact of β becomes littler as its value increments. Thus, the non-Newtonian property can be one of the variables, which resist the spreading of blood through membranes in the human body. Figure 12 articulates another obstruction for the stream of fluid is the axial magnetic field parameter M. This figure gives the impact of M on the distribution of stream and temperature, respectively. While M increments the flow, velocity reduces; however, the temperature distribution increases. Adequately, the adjustment in velocity is inversely proportional to that of the parameter M. The use of a transverse magnetic field to an electrically directing fluid gives rise a resistive-type force called the Lorentz force. This power tends to back off the movement of the fluid in the boundary layer and to expand its temperature. Moreover, the effects on the thermal and the flow fields increment as the quality of the magnetic field increments. Also, the influence of the magnetic field on the velocity distribution is increased significantly as compared with the same influence on the temperature profile as presented in this figure. Finally, Fig. 13 shows the variations of the local skin friction coefficient Cf and the heat transfer rate (the local Nusselt number Nu) with two types of nanoparticles (Au and Al2O3) for both cases of magnetic field parameter (M = 0 and M = 1). It is noticed from this figure that the local skin friction coefficient decreases with increasing φ for the two types of nanoparticles. On the other hand, the lowest skin friction coefficient is recorded for the gold blood compared to alumina blood. Furthermore, the skin friction coefficient of magneto-nanofluids is greater than that of nanofluids if the magnetic field is neglected. Also, it is observed from Fig. 13 that the local Nusselt number decreases with increasing φ for Au and Al2O3 as nanoparticles. These results are similar to those reported by Afify and Abd El-Aziz [55]. Moreover, the local Nusselt number of magneto-nanofluids is lower than that of nanofluids if the magnetic field is neglected.

Tables 4 and 5 present the numerical results of the local Nu and the local skin friction Cf. From Table 4, we notice that for pure fluid (without nanoparticles ϕ=0) for heat source/sink, as the surface temperature variation n parameter increases, the Nusselt number increases, whereas as the heat generation source (q > 0) increases, the Nusselt number decreases. On the other hand, for fluid with suspension of gold (Au) and alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles, as n parameter increases, the Nusselt number increases, whereas the Nusselt number decreases as heat generation increases. Also, from Table 5, we observe that for both cases of pure fluid and nanofluid, as the porous medium inertia coefficient γ increases, the skin friction increases. As the non-Newtonian property β and the permeability parameter Da increase, the skin friction decreases. While, as γ and β increase, the Nusselt number decreases. Also, as Da increases, the Nusselt number increases. Moreover, from Table 5 for nanofluid, we notice that the values of the local skin friction for gold as nanoparticles are less than these values for alumina as nanoparticles.

Conclusions

This study is focused on investigating a numerical solution of non-Newtonian Casson nanofluid flow underlying an axisymmetric spreading surface through a non-Darcian porous medium with heat source/sink. The system of PDEs are reduced to nonlinear ODEs and solved numerically by Chebyshev pseudospectral (CPS) method. Fine agreements were found in the comparisons, verifying the accuracy and efficiency of the present numerical code. Two cases of nanofluid have been considered. The first case is gold (Au) and alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles with blood as base non-Newtonian bio-fluid. The second case is gold and alumina nanoparticles with water as base Newtonian fluid. Based on this study, the main conclusions emerging are as follows:

-

1.

The thermal boundary layer thickness is related to the increased thermal conductivity of the nanoparticles. In fact, the nanoparticles with high thermal conductivity (gold) have better enhancement on heat transfer compared to alumina, i.e., the effectiveness of adding gold to the water and blood is higher than adding alumina.

-

2.

The implication of a nanoparticle into bio-fluid can modify the stream design.

-

3.

The Casson property can be one of the variables, which resist the spreading of blood through membranes in the human body.

-

4.

The velocity increases with permeability parameter increasing. Physically, when the openings of the permeable medium are extensive, then the opposition of the medium might be disregarded.

-

5.

The thermal boundary layer decreases for heat absorption sink. Physically, the heat absorption sink may be exploited to successfully cool the regime.

-

6.

One of the most important applications of nanotechnology in the field of medicine is the use of nanoparticles (gold molecules) in chemotherapy to get rid of cancer cells.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- (r, ϕ, z):

-

Cylindrical polar coordinate

- T w(r):

-

Surface temperature

- k nf :

-

The effective thermal conductivity of the nanofluid

- Q 0 :

-

The heat source/sink coefficient

- k s :

-

The thermal conductivity of solid

- C P :

-

Heat capacity at constant pressure

- T ∞ :

-

Ambient temperature

- c :

-

The inertia coefficient

- F :

-

Constant

- H :

-

Thickness of film (membrane)

- K :

-

The effective thermal conductivity

- n :

-

Surface temperature variation parameter

- Q :

-

The heat source/sink parameter

- Q :

-

The volume flux

- T :

-

Temperature of the nanofluid

- ρ s :

-

Density of solid fraction

- σ s :

-

Electrical conductivity of solid fraction

- β :

-

The upper limit of apparent viscosity coefficient parameter (non-Newtonian property)

- α nf :

-

Thermal diffusivity of nanofluid

- μ f :

-

Dynamic viscosity of fluid fraction

- ρ nf :

-

Density of nanofluid

- σ f :

-

Electrical conductivity of fluid fraction

- σ nf :

-

Electrical conductivity of nanofluid

- eij :

-

Component of the deformation rate

- ρ f :

-

Density of fluid fraction

- φ :

-

Nanoparticle volume fraction

- B(r) = B 0/r :

-

Non-uniform magnetic field

- K(r):

-

Non-uniform permeability

- Cf :

-

Skin friction coefficient

- k nf :

-

The effective thermal conductivity of the nanofluid

- (ρ c p)nf :

-

The heat capacitance of nanofluid

- k f :

-

The thermal conductivity of fluid

- p y :

-

Yield stress of the nanofluid

- D 1, D 2, D 3 :

-

Constants in Eq. (9)

- μ nf :

-

The effective plastic dynamic viscosity of the Casson non-Newtonian nanofluid in Eq. (10)

- ν f :

-

Kinematic viscosity of fluid fraction

- ∞:

-

Far field

- A :

-

Empirical constant

- Da :

-

Permeability parameter

- f :

-

Base fluid

- f :

-

Similarity function

- M :

-

Magnetic parameter

- nf:

-

Nanofluid

- Nu:

-

Nusselt number

- Pr:

-

Prandtl number

- s :

-

Nanosolid particles

- u, w :

-

Velocity components along the r and z directions, respectively

- w :

-

Condition at the surface

- γ :

-

Porous medium inertia coefficient parameter

- η :

-

Similarity variable

- θ :

-

Dimensionless temperature

References

Choi, S.U.S.: Enhancing Thermal Conductivity of Fluids with NanoparticlesASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congress and Exp, San Francisco (1995)

Pozhar, L.A., Kontar, E.P., Hua, M.Z.C.: Transport properties of nanosystems: viscosity of nanofluids confined in slit nanopores. J. Nanosci. and Nanotech. 2(2), 209–227 (2002)

Pozhar, L.A.: Structure and dynamics of nanofluids: theory and simulations to calculate viscosity. Phys. Rev. E. 61(2), 1432–1446 (2000)

Pozhar, L.A., Gubbins, K.E.: Quasi hydrodynamics of nanofluid mixtures. Phys. Rev. E. 56(5), 5367–5396 (1997)

Ghassemi, M., Shahidian, A., Ahmadi, G., Hamian, S.: A new effective thermal conductivity model for a bio-nanofluid (blood with nanoparticle Al2O3). Int. Comm. Heat Mass Transfer. 37, 929–934 (2010)

Chamkha, A.J., Aly, A.M.: MHD free convection flow of a nanofluid past a vertical plate in the presence of heat generation or absorption effects. Chem. Eng. Comm. 198, 425–441 (2011)

Gorla, R.S.R., Chamkham, A.J.: Natural convective boundary layer flow over a horizontal plate embedded in a porous medium saturated with a nanofluid. J. Modern Physics. 2, 62–71 (2011)

Khan, W.A., Pop, I.: Boundary layer flow past a stretching surface in a porous medium saturated by a nanofluid: Brinkman-Forchheimer model. PLoS One. 7(10), 1–6 (2012)

Ashorynejad, H.R., Sheikholeslami, M., Pop, I., Ganji, D.D.: Nanofluid flow and heat transfer due to a stretching cylinder in the presence of magnetic field. Heat Mass Transf. 49(3), 427–436 (2013)

Uddin, M.J., Bég, O.A., Amin, N.S.: Hydromagnetic transport phenomena from a stretching or shrinking nonlinear nanomaterial sheet with Navier slip and convective heating: a model for bio-nano-materials processing. J. Magnetism Magnetic Materials. 368, 252–261 (2014)

Khan, J.A., Mustafa, M., Hayat, T., Farooq, M.A., Alsaedi, A., Liao, S.J.: On model for three-dimensional flow of nanofluid: an application to solar energy. J. Molecular Liquids. 194, 41–47 (2014)

Ferdows, M., Khan, M.S., Bég, O.A., Azad, M.A.K., Alam, M.M.: Numerical study of transient magnetohydrodynamic radiative free convection nanofluid flow from a stretching permeable surface. J. Process Mech. Eng. 228(3), 181–196 (2014)

Sreedevi, P., Reddy, P.S., Rao, K.V.S.N., Chamkha, A.J.: Heat and mass transfer flow over a vertical cone through nanofluid saturated porous medium under convective boundary condition with suction/injection. J. Nanofluids. 6, 478–486 (2017)

Prabhavathi, B., Reddy, P.S., Vijaya, R.B., Chamkha, A.J.: MHD boundary layer heat and mass transfer flow over a vertical cone embedded in porous media filled with Al2O3-water and Cu-water nanofluid. J. Nanofluids. 6, 883–891 (2017)

Hayat, T., Khan, M.I., Waqas, M., Alsaedi, A., Farooq, M.: Numerical simulation for melting heat transfer and radiation effects in stagnation point flow of carbon-water nanofluid. Computer Method in Applied Mech. Eng. 315, 1011–1024 (2017)

Zeeshan, A., Shehzad, N., Ellahi, R.: Analysis of activation energy in Couette-Poiseuille flow of nanofluid in the presence of chemical reaction and convective boundary conditions. Results Phys. 8, 502–512 (2018)

Sreedevi, P., Reddy, P.S., Chamkha, A.J.: Magneto-hydrodynamics heat and mass transfer analysis of single and multi - wall carbon nanotubes over vertical cone with convective boundary condition. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 135, 646–655 (2018)

Mendu, U., Venumadhav, K.: Analysis of heat and mass transfer enhancement in mixed convection in Brinkman–Darcy flow of Au-water and Ag-water nanofluids. J. Nanofluids. 8(1), 230–237 (2019)

Hammouch, Z., M Guedda, M.: Existence and non-uniqueness of solution for a mixed convection flow through a porous medium. J. App. Math. & informatics. 31, 631–642 (2013)

Hammouch, Z., Mekkaoui, T., Belgacem, F.B.: Double-diffusive natural convection in porous cavity heated by an internal boundary. Math. Eng., Sci. Aeorospace. 7(3), 1–14 (2016)

Haq, R.U., Hammouch, Z., Khan, W.A.: Water-based squeezing flow in the presence of carbon nanotubes between two parallel disks. Therm. Sci. 20(6), 1973–1981 (2016)

Shafiq, A., Hammouch, Z., Sindhu, T.N.: Bioconvective MHD flow of tangent hyperbolic nanofluid with newtonian heating. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 133, 759–766 (2017)

Shafiq, A., Hammouch, Z., Turab, A.: Impact of radiation in a stagnation point flow of Walters’ B fluid towards a Riga plate. Thermal Sci. Eng. Progress. 6, 27–33 (2018)

Nakamura, M., Sawada, T.: Numerical study on the flow of a non-Newtonian fluid through an axisymmetric stenosis. J. Biomech. Eng. 110, 137–143 (1988)

Wang, C.Y.: Effect of spreading of material on the surface of a fluid-an exact solution. Int. J. Nonlinear Mech. 6, 255–262 (1971)

Wang, C.Y.: Heat transfer to an underlying fluid due to the axisymmetric spreading of material on the surface. Appl. Sci. Res. 45, 367–376 (1988)

Lin, C.R., Chen, C.K.: Exact solutions of heat transfer of a fluid underlying the axisymmetrical spreading on the surface. J. Math. Anal. Appls. 176, 301–309 (1993)

T Eldabe, N., Mohamed, M.A., Hassan, M.A.: Heat and mass transfer of MHD flow of non-Newtonian fluid through porous medium underlying an axisymmetric spreading surface. Far East J. Appl. Math. 19, 265–296 (2005)

Seddeek, M.A., Salem, A.M.: The effect of an axial magnetic field on the flow and heat transfer about a fluid underlying the axisymmetric spreading surface with temperature dependent viscosity and thermal diffusivity. Comput. Mech. 39, 401–408 (2007)

Elgazery, L.J.S.: Numerical simulation for biviscosity fluid flow through a porous medium under the effects of variable properties. Special Topics Rev. Porous Media. 3(1), 1–11 (2012)

Stanojevic, M., Lazarevic, B., Radic, B.: Review of membrane contactors designs and applications of different modules in industry. FME Trans. 31, 91–98 (2003)

Oztop, H.F., Abu-Nada, E.: Numerical study of natural convection in partially heated rectangular enclosures filled with nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 29, 1326–1336 (2008)

Annasagaram, S.R., Amanulla, C.H., Nagendra, N., Reddy, S.N.M., Bég, O.A.: Hydromagnetic non-Newtonian nanofluid transport phenomena from an isothermal vertical cone with partial slip: aerospace nanomaterial enrobing simulation. Heat Transfer- Asian Res. 47, 203–230 (2018)

Balakrishna, S., Mohan, S.R., Reddy, G.V., Varma, S.V.K.: Effects of chemical reaction on unsteady MHD Casson fluid flow past a moving infinite inclined plate through porous medium. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Computing. 8(7), 18658–18666 (2018)

Aminossadati, S.M., Ghasemi, B.: Natural convection cooling of a localized heat source at the bottom of a nanofluid-filled enclosure. Eur. J. Mech. B/Fluids. 28, 630–640 (2009)

Mahmoudi, A.H., Pop, I., Shahi, M.: Effect of magnetic field on natural convection in a triangular enclosure filled with nanofluid. Int. J. Thermal Sci. 59, 126–140 (2012)

Sheikholeslami, M., Abelman, S., Ganji, D.D.: Numerical simulation of MHD nanofluid flow and heat transfer considering viscous dissipation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 79, 212–222 (2014)

Brinkman, H.C.: The viscosity of concentrated suspensions and solution. J. Chem. Phys. 20, 571–581 (1952)

Fox, L., Parker, I.B.: Chebyshev Polynomials in Numerical Analysis. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1968)

Gottlieb, D., Orszag, S.A.: Numerical Analysis of Spectral Methods: Theory and Applications. SIAM, Philadelphia (1977)

Canuto, C., Hussaini, M.Y., Quarterini, A., Zang, T.A.: Spectral Methods in Fluid Dynamics. Springer, Berlin (1988)

Nasr, H., Hassanien, I.A., El-Hawary, H.M.: Chebyshev solution of laminar boundary layer flow. Int. J. Comput. Math. 33, 127–132 (1990)

Voigt, R.G., Gottlieb, D., Hussaini, M.Y.: Spectral Methods for Partial Differential Equations. SIAM, Philadelphia (1984)

Elbarbary, E.M.E., Elgazery, N.S.: Chebyshev finite difference method for the effect of variable viscosity on magneto-micropolar fluid flow with radiation. Int. Comm. Heat Mass Transfer. 31, 409–419 (2004)

Elbarbary, E.M.E., Elgazery, N.S.: Chebyshev finite difference method for the effects of variable viscosity and variable thermal conductivity on heat transfer from moving surfaces with radiation. Int. J. Thermal Sci. 43, 889–899 (2004)

Elbarbary, E.M.E., Elgazery, N.S.: Flow and heat transfer of a micropolar fluid in an axisymmetric stagnation flow on a cylinder with variable properties and suction. Acta Mech. 176, 213–229 (2005)

Elgazery, N.S.: An implicit-Chebyshev pseudospectral method for the effect of radiation on power-law fluid past a vertical plate immersed in a porous medium. Comm. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulation. 13, 728–744 (2008)

Elgazery, N.S., Hassan, M.A.: The effects of variable fluid properties and magnetic field on the flow of non-Newtonian fluid film on an unsteady stretching sheet through a porous medium. Comm. Numer Methods Eng. 24(12), 2113–2129 (2008)

Elgazery, N.S., Abd Elazem, N.Y.: Effects of viscous dissipation and Joule heating for natural convection in a hydromagnetic fluid from heated vertical wavy surface. Z. Naturforsch. 66a, 427–440 (2011)

El-Sayed, M.F., Elgazery, N.S.: Effect of variations in viscosity and thermal diffusivity on MHD heat and mass transfer flow over porous inclined radiate plane. Eur. Physical J. Plus. 126, 124–140 (2011)

Elgazery, N.S.: Effects of variable fluid properties on natural convection of MHD fluid from a heated vertical wavy surface. Meccanica. 47(5), 1229–1245 (2012)

Elgazery, N.S., El-Sayed, M.F.: Effects of magneto-marangoni convection with variable properties on non-newtonian biviscosity fluid over stretching sheet in porous medium. J. Porous Media. 17(10), 901–912 (2014)

Huang, K.H., Tsai, R., Huang, C.H.: Chebyshev finite difference approach to modeling the thermoviscosity effect in a power-law liquid film on an unsteady stretching surface. J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 165, 1351–1356 (2010)

Elbarbary, E.M.E., El-Sayed, M.S.: Higher order pseudospectral differentiation matrices. Appl. Numer. Math. 55, 425–438 (2005)

Afify, A.A., Abd El-Aziz, M.: Lie group analysis of flow and heat transfer of non-Newtonian nanofluid over a stretching surface with convective boundary condition. Pramana – J. Phys. 88, 31–41 (2017)

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express his thanks to the reviewers for the insightful comments and suggestions which have improved aspects of the work.

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NSE analyzed and interpreted the data, performed numerical solution for the governing equations of the present work, wrote the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Elgazery, N.S. Flow of non-Newtonian magneto-fluid with gold and alumina nanoparticles through a non-Darcian porous medium. J Egypt Math Soc 27, 39 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-019-0017-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-019-0017-x