Abstract

Introduction

This systematic review aimed to analyse the performance of the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) strategy in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and how its implementation has embraced advancement in information technology, big data analytics techniques and wealth of data sources.

Methods

HINARI, PubMed, and advanced Google Scholar databases were searched for eligible articles. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols.

Results

A total of 1,809 articles were identified and screened at two stages. Forty-five studies met the inclusion criteria, of which 35 were country-specific, seven covered the SSA region, and three covered 3–4 countries. Twenty-six studies assessed the IDSR core functions, 43 the support functions, while 24 addressed both functions. Most of the studies involved Tanzania (9), Ghana (6) and Uganda (5). The routine Health Management Information System (HMIS), which collects data from health care facilities, has remained the primary source of IDSR data. However, the system is characterised by inadequate data completeness, timeliness, quality, analysis and utilisation, and lack of integration of data from other sources. Under-use of advanced and big data analytical technologies in performing disease surveillance and relating multiple indicators minimises the optimisation of clinical and practice evidence-based decision-making.

Conclusions

This review indicates that most countries in SSA rely mainly on traditional indicator-based disease surveillance utilising data from healthcare facilities with limited use of data from other sources. It is high time that SSA countries consider and adopt multi-sectoral, multi-disease and multi-indicator platforms that integrate other sources of health information to provide support to effective detection and prompt response to public health threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite scientific development to strengthen the health system to protect and promote human health, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) continues to be confronted by longstanding, emerging, and remerging infectious disease threats [1, 2]. The region vulnerability to infectious disease epidemics is driven by favourable climatic and ecological conditions for harbouring pathogens and their vectors in an environment with high human and animal interactions [3, 4]. Migration of wild animals and birds, frequent uncontrolled movements of people, commodities, animals and animal products across the national and international borders pose additional threats to the spread of infectious diseases [5]. Unfortunately, the region has a relatively low capacity for risk management of disease epidemics, mainly due to inadequate resources for early detection, identification, and prompt response [6, 7]. The failure in the early detection and response to epidemics in SSA is attributed to several factors, including deficiency in the development and implementation of surveillance and response systems against infectious disease outbreaks [8].

Before 1998, most countries in Africa implemented surveillance systems through vertical programmes of specific diseases of national and /or international priority. These included malaria, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and vaccine-preventable diseases. Epidemiological data were collected mainly at the health care facility level and in outreach health service settings [9, 10]. This situation led to fragmented and inefficient disease monitoring systems in many aspects, including resource allocation, flow and use of information and country capacity to detect and respond [9]. In response to an increased frequency of emerging and re-emerging diseases causing high morbidity and mortality in Africa, in 1998, the World Health Organisation (WHO) Regional Committee for Africa adopted a strategy called Integrated Disease Surveillance [9, 11]. The intent was to create and implement a comprehensive, integrated, action-oriented, district-focused public health surveillance for African countries [9]. In 2001 the strategy was renamed Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) to emphasise the critical linkage between surveillance and public health action and response [12].

IDSR functions are categorised into core and support functions. The core functions include identification of cases, investigation and confirmation, registration, case notification/reporting, data analysis and interpretation, response to the situation, communication and provision of two-way feedback, evaluation of the interventions, and preparation for emergency occurrences. The support functions include guidelines, laboratory capacity, supervision, training, resources and coordination at all health system levels [13]. The IDSR organisation structure allows surveillance information to flow from the low levels (community and facility) where data is generated through the district and national levels up to the World Health Organization. The IDSR implementation leverages the purpose and scope of the International Health Regulations 2005 [11].

During the past 20 years, the IDSR framework has been used in 94% (44/47) of the countries in the WHO African region to enhance capacity for surveillance for priority diseases, conditions, and events [14,15,16]. In most of these countries, the strategy has been implemented for about two decades, and the priority disease list required for reporting has been revised and increased [17]. Having a large number of diseases monitored by the public surveillance system creates implementation challenges. Low laboratory diagnostic capacity, low utilisation of the primary healthcare system and limited analytical skills and capacities in managing large and complex data result in unconfirmed and incomplete data and minimal utilisation of the data generated by the conventional system. Besides, the African continent has recently experienced major epidemics, including Ebola virus disease, dengue fever, cholera, yellow fever and coronavirus disease 2019, which spread faster and further due to high global connectivity, inadequate detection and risk management, and might easily be missed by the routine monitoring systems.

Over the years, the IDSR has relied heavily on the routine health management information system (HMIS) implemented at the facility and district levels of the health systems [16]. However, technology advancement and new communication platforms such as social and news media are growing in Africa, bringing more opportunities to incorporate digital data into surveillance information to complement passive facility-based surveillance. Since its adoption IDSR effectiveness and performance in SSA have been assessed, focusing on its functions. However, assessments on how the challenges and opportunities coming with IDSR evolved, how the technology expansion and the availability of other data sources relevant for surveillance have been embraced in monitoring, detecting and managing epidemics have not been documented with certainty [11, 14]. This systematic review aimed to analyse the performance of the IDSR strategy in Sub-Saharan Africa and how its implementation has embraced advancement in information technology, big data analytics techniques and wealth of data sources, as well as the One Health approach. The gaps, challenges and opportunities identified are used to propose appropriate strategies to improve surveillance in the region.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review was guided by the following overarching question: Does IDSR generate information that drives early detection of and response to infectious disease outbreaks? Specific questions were: (i) Has IDSR improved health data quality and utilisation during its 20 years of implementation in SSA?; (ii) What are the challenges and opportunities for IDSR to improve early detection and prompt response to infectious diseases in SSA? The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols 2015 checklist [18]. Three databases, namely HINARI, PubMed, and advanced Google Scholar, were searched using Boolean operators. The search terms were Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response, Integrated Disease Surveillance, Health Management Information Systems, District Health Information System and Sub Saharan Africa or individual member country. The search was limited to studies published in the English language between January 1998 and December 2020. An additional search was conducted using the Google search engine on the World Wide Web and hand-searching from the reference list of the screened articles. Other sources were the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and ministries websites of individual Sub-Saharan African countries.

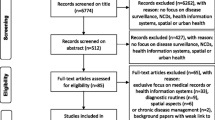

The review involved two-stage screening, title/abstract screening and full-paper screening. The inclusion criteria were: the study must involve at least one of the SSA countries, clearly describe the evaluation of the IDSR system, focuses on at least one of the IDSR functions and/or systems attributes. The review excluded studies with abstracts without full text, not in English, reviews and newsletters. Two of the authors (IRM and LEGM) extracted eligible articles independently, and any disagreements between them on inclusion or exclusion were resolved by discussion and consensus. The linked descriptive search requests that were developed and search results from each database are presented in Table 1. Further exclusion of the article was performed during the data collection process after its full-text review. The extracted data related to the IDSR core and support functions’ performance, challenges associated with its implementation and improvement opportunities were summarised using the thematic analysis method.

Results

Literature selection

A total of 1,809 articles were initially identified using the key search descriptors. A large number of articles (1,311) were irrelevant or duplicate and were excluded. The 498 remaining abstracts were screened further, and 412 were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of the remaining 86, full-text articles were screened, and 45 studies met the inclusion criteria and hence, were selected for detailed reviews (Fig. 1). Of the 45 studies, 35 were country-specific, seven covered the SSA region, and three covered 3–4 countries. Of the 47 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, country-specific studies were available for 20 (42.6%) countries. A total of 26 studies assessed the IDSR core functions, while 43 the support functions and 24 focused on either core or support functions. Twenty-four studies addressed both the core and support functions. Most of the studies involved Tanzania (9), followed by Ghana (6) and Uganda (5) (Table 2).

Performance of IDSR strategy

The adoption and implementation of the IDSR strategy during the past 20 years have shown some improvements in several countries' disease surveillance activities. These include the integration of the surveillance functions of the categorical (or vertical) disease control programmes; implementation of standard surveillance, laboratory and response guidelines; improved timeliness and completeness of surveillance data, as well as increased national-level review and use of surveillance data for the response [14, 15]. However, most efforts to improve IDSR in SSA focused on the support functions rather than core functions. The successes of the desire for integration of the disease surveillance strategies in SSA have been documented in several countries, including Ghana, Ethiopia, Botswana, Kenya, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Uganda [56]. These include the efficient utilisation of the vertical programme surveillance mechanisms that provided functional infrastructure and trained personnel [56, 57].

IDSR core functions

Improvements in IDSR system attributes such as completeness and timeliness of data reporting have been observed in Uganda, Malawi and Ghana [24, 35, 49, 51]. By the end of 2017, 68% of the countries in the WHO Africa Region had achieved the timeliness and completeness threshold of at least 80% of the reporting facilities. There was an improvement in timeliness of monthly and weekly reporting from 59 and 40% in 2012 to 93 and 68% in 2016, respectively [14]. During the same period of time, completeness of monthly and weekly reporting improved from 69 to 100% and 56 to 78%, respectively [14]. However, over the years, routine HMIS has remained the primary data source for IDSR in SSA. The routine HMIS in several SSA countries is characterised by persistent incompleteness and other data quality issues [58,59,60]. Studies in Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria and Tanzania have reported that case registration at a health care facility is also a challenge. There is a failure in comprehensively entering the appropriate patient information in the registers, and in some cases, diagnoses are either not recorded or wrongly recorded [60,61,62,63,64]. Moreover, high levels of mismatch between the register records and report forms and electronic District Health Information System-2 (DHIS-2) have been observed [60]. In Ethiopia and Liberia, IDSR data generated through HMIS were under-utilised due to poor data management and analysis skills [19, 22, 32]. A high level of mismatch between the HMIS registers' entries, tally sheets and the DHIS-2 database has also been reported in some countries in Africa [60, 65]. Thus, despite some progress in recent years, the core IDSR data source is still weak and inaccurately reflects what is generated from the primary healthcare facility levels [60].

Studies in Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia have reported that several health facilities lack copies of the IDSR Technical Guidelines for Standard Case definitions; and that laboratories are ill-equipped to provide confirmation of any suspected priority notifiable infectious disease [10, 25, 60]. Lack of capacity for timely clinical screening, referral, diagnosis, notification, treatment and containment of suspected cases has been documented in Africa [66, 67]. Coordination of case definition reporting protocols across programmes was identified as a necessary step towards improving IDSR completeness and timely reporting in Uganda [52]. Moreover, since most primary level health care facilities lack diagnostic capabilities, the generated data rely on a syndromic approach, with low specificity [68]. Syndromic surveillance remains more useful at the community level for early detection and reporting of disease signals, which should be immediately verified and responded to by the primary health care facilities. Health care utilisation in many low-income countries is limited, and that only a proportion of people have access to conventional healthcare facilities. The utilisation frequency is higher among urban than rural populations. Several SSA countries have reported a frequency of between 40.0 and 87.3% of their population seeking care from conventional health care facilities [69,70,71,72].

IDSR support functions

In terms of IDSR support functions, of the 47 countries in the WHO Africa Region, 94% were implementing the IDSR strategy, and 45 (85%) have initiated training at the sub-national level [14]. Thirty-three (70%) of the countries were using the electronic IDSR (eIDSR) system, and over two thirds (68%) had a feedback mechanism for sharing national surveillance data [14]. The introduction of the eIDSR using short message service for reporting weekly epidemiological data has proved to be a powerful tool that empowers health workers and addresses many of the barriers associated with paper-based reporting [38, 47, 52]. At the same time, the development of generic data analysis has guided enhanced data quality and management in Zimbabwe [73]. In terms of key performance indicators, there was a substantial increase in the number of countries that had adopted the IDSR guidelines and conducted training of healthcare workers at all levels [14].

Discussion

Challenges of IDSR

This review indicates that in most countries, data generated through the routine HMIS, which is the key source of IDSR, are rarely assessed for their quality, analysed and used to support decision-making [74]. Several studies in SSA have revealed weaknesses in case identification and recording at the primary healthcare facilities associated with several factors including limited skills among health workers due lack of training and refresher courses, patient-load versus human resource availability, low motivation and inadequate HMIS-related resources [15, 24, 44, 45, 49, 60]. The quality of the data remains a challenge, with incomplete and inconsistent data frequently being reported at different levels of the surveillance system. Moreover, HMIS data are considered to mainly reflect the population seeking care from health care facilities.

In Ethiopia, Liberia and Tanzania, assessments of the HMIS have identified some data quality issues and lack of use of the generated data [32, 43, 60, 75]. In a study in Ethiopia, though the surveillance system was found to be simple, useful, flexible, acceptable and representative, it lacked regular data analysis and feedback [22]. Moreover, studies in Kenya and Nigeria have indicated gaps between knowledge and practice of disease surveillance among health care workers [76, 77]. Incomplete data filing and inadequate organisation have been reported as an inbuilt shortcoming at all levels of IDSR in SSA [25, 26, 78]. Routine data analysis is still insufficient at facility and district levels in most countries, mainly due to the lack of clear guidelines for analysing data, shortage of skilled personnel, poor understanding of the use of surveillance data in planning, and inadequate infrastructure, including warehouses, computers, databases, data mining systems and analytical software [43, 44, 46, 51, 60].

A few countries (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Liberia, Uganda) have reported analysing and used routine HMIS data at sub-national levels [32, 74]. In both Liberia [32] and Tanzania [43], it was found that analysis and data use have not been given adequate attention. In addition to poor data management and analysis skills, some studies have reported under-utilisation of IDSR data at all levels due to poor data management and analysis skills [32, 42, 43, 60]. The culture of data analysis was lacking, and the relevance of surveillance data for decision making at sub-national levels was grossly underestimated. The use of paper-based reporting was likely to lead to severe limitations in the transmission of the data from the point of generation to a higher level mainly because of the inefficient report review and approval processes, manual routing of reports and running out of recording and reporting forms [25, 46]. Despite significant investment in early outbreak detection in SSA, there is very little evidence that even high HMIS data utilisation will influence early detection [79].

For the integrated system to be efficient, it requires strong coordination and communication, a clear organisation structure, adequate resources [80, 81], and reliable data sources. Integration may range from interconnectivity, which requires a simple transfer of files with basic applications, to complex convergent integration, which involves merging technology with processes, knowledge, and human performance. IDSR strategy strives for the concurrent integration route, but most countries have not achieved total integration. Implementation of the strategy is partially done [14, 35], and there is more focus on technical aspects than organisational and human resource issues hence impair the performance of the systems [49, 82]. Nevertheless, some countries such as Uganda have rectified those systemic challenges and reported improvement in the implementation [50].

Opportunities for improving IDSR

Health information systems

In SSA, several government ministries, agencies, and academic and research institutions are involved in managing different aspects of the health information systems. The ministries of health run the routine HMIS as the major source of information for decision making and planning. National Statistical Offices are responsible for most of the nation-wide household demographic and health surveys as well as population census [74]. Other key health-related information systems include civil registration, demographic surveillance sites and research outputs [83]. Demographic surveillance sites function in several countries, but the data generated are not integrated into the national health information system because of concerns about representativeness [74]. Besides, health research and academic institutions are increasingly generating evidence on human and animal health that could be used for disease surveillance purposes. However, most of the findings are mainly used for estimating national disease distribution rather than for planning national disease control programmes [84].

A warning of an impending epidemic can help relevant authorities and communities to prepare and take immediate actions to reduce morbidities and mortalities. Many of the epidemic diseases are highly sensitive to long-term changes in climate and short-term fluctuations in weather. Meteorological data are made available daily by the National Meteorological Agencies, yet they are rarely used to monitor the occurrence of diseases. Meteorological data can be combined with geospatially referenced data, population densities or road networks to generate estimates of environmental indicators relevant to infectious diseases [68]. However, such information is not available for planning, disease surveillance and outbreak management. It is recommended that the SSA governments consider establishing national platforms for infectious disease epidemics early warning systems and develop action plans for their operationalization, including resource mobilization and engagement with key stakeholders.

It is critical for a good and efficient surveillance system to incorporate other sources such as mortality data from demographic surveys, environmental data, vital statistics and civil registration, antimicrobial resistance, systematic surveys, meteorological data and research data. In most countries, despite an enormous amount of data generated by these systems, they run in parallel and independently, not well-coordinated, and sharing of information between them is minimal. Each of the existing systems operates its data collection and utilization framework. Moreover, much of the information is generated outside the health sectors – making it not readily available for disease surveillance purposes. It is a fact that the innovations, including the use of big data and artificial intelligence, could transform infectious disease surveillance and response and complement the existing traditional disease surveillance systems and improve detection and response to epidemics [68].

Laboratories play an important role in the prompt diagnosis of infectious diseases. The findings of this review have shown that IDSR is challenged by inadequate diagnostic capacities at all levels of the health system, especially in terms of staff levels, skill sets and infrastructure. It is critical, therefore, that countries support the efforts to strengthen laboratory capacities for the detection of a wide range of pathogens in relation to the IDSR priority diseases. Moreover, laboratory networking should be encouraged and should involve both national, regional and research reference laboratories. To address the gaps in knowledge, it is important to strengthen the laboratory management information systems (LIMS), recruit adequate staff who are well trained and motivated as well as the need for periodic support supervision of the surveillance activities. The plan by the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention to establish and operationalize a Regional Integrated Surveillance and Laboratory Network is commended. This network is expected to coordinate and connect the continent’s analytical, surveillance, and emergency-response assets [85].

Digital disease surveillance

An effective epidemic intelligence should contain both indicator-based and event-based surveillance. Globally, with the use of information technologies, an event-based surveillance approach is being promoted to complement the traditional “indicator-based” surveillance approach as part of the components of epidemic intelligence [86]. There have been growing interests in event-based internet bio-surveillance systems also referred to as digital disease surveillance (DDS) in recent years. DDS is the use of data generated outside the public health system for disease surveillance [86]. It involves the aggregation and analysis of data available on the internet, such as search engines, social media and mobile phones, and not directly associated with patient illnesses or medical encounters. It has been shown that digital approaches in surveillance improve the timeliness and depth of surveillance information in high-income countries [86, 87]. Recently, DDS has been used in responding to COVID-19 through case detection, contact tracing and isolation, and quarantine in several countries, including Taiwan, New Zealand and Thailand [88, 89]. In about 30 countries, algorithmic contact tracing through the use of a cell phone app or operating system has been deployed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [89].

There is growing interest in using digital surveillance approaches to improve monitoring and control of infectious disease outbreaks [86]. However, such applications are scarce in Africa, and few studies have shown a direct connection between DDS and public health actions. So far, DDS has demonstrated its potential in early detection and response to Ebola and COVID-19 epidemics [90,91,92,93,94,95]. In a recent systematic review of the mobile-based infectious disease outbreak management systems (SORMAS) [93, 95, 96] was identified as having capacities to fully integrate data from case management, contact tracing, laboratory work and surveillance components. Currently, the Africa Centre’s for Disease Control and Prevention is implementing a pilot Programme in Ghana, Liberia, Madagascar, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and South Africa to develop digital surveillance indicators and online disease dashboards based on social media to inform infectious disease surveillance [97]. Moreover, there are ongoing efforts to create real-time data sharing platforms for disease surveillance using mobile technologies to allow centralized data management and use [96]. This is expected to strengthen real-time surveillance of infectious diseases in the continent, guide interventions, and build capacity in big data approaches for outbreak prediction, analysis and prevention.

With the proliferation of information technologies and increased ownership of mobile phones in SSA, there are large amounts of data on social media blogs, chatrooms, and local news reports that may provide governments and other stakeholders’ clues about disease outbreaks time and place daily. Such data are essential raw materials for DDS. Advancements in information technology and information sharing give rise to infodemiology – defined as the science of distribution and determinants of information in an electronic medium, specifically the internet [90]. To date, Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED-mail) [98] and HealthMap [99] are among the several leading efforts in digital surveillance. The World Health Organization routinely uses HealthMap, ProMED and similar systems to monitor infectious disease outbreaks and inform public health officials and the general public [100]. The key advantages of DDS include speed and volume, which may increasingly help health officials to spot outbreaks quickly and cheaply [96].

Community event-based surveillance

Community-based surveillance (CBS) is defined as the systematic detection and reporting of events of public health significance within a community by community members [101]. Community engagement has long been an essential part of both human and animal health [102,103,104,105]. CBS has played a significant role in smallpox, guinea worm and polio eradication programmes [103]. Recently, CBS was reported as an important component in response to the West African Ebola virus disease outbreak of 2014–2016, where community health workers and volunteers worked together in early detection and timely reporting to the health system [106]. With CBS, public engagement is being transformed through participatory surveillance systems that enable the community to directly report disease events via information technology and communication tools [107]. Several CBS systems have been described and demonstrated their accuracy and sensitivity, their ability to provide more timely disease activity measures, and their usefulness in identifying risk groups, assessing the burden of illness and informing disease transmission models [108, 109]. CBS can provide early warning for emerging events by engaging the communities to detect potential public health events and connecting individuals to health services [3, 110, 111]. In a study in Ivory Coast, following the implementation of CBS, 5 to eightfold increases in reporting of suspected measles and yellow fever clusters have been reported [110]. These findings suggest that CBS can be used to strengthen the detection and reporting capabilities for several suspect priority diseases and events.

The WHO Technical Guidelines on IDSR [13, 17] highlight the need for CBS. This is because most of the health problems and events happen at the community level, thereby placing the community as the primary sensor of the disease signals. Thus, putting a surveillance mechanism to obtain information at the community level is an added advantage to capture diseases and public health events at their early stages to allow effective preparedness and response, thereby managing disease outbreaks at the source. Despite the relevance of the inclusion of community information in surveillance, by the end of 2017, only 32 (68%) of the 44 countries in the WHO Africa region had commenced CBS, and 35 (74%) had event-based surveillance [14]. However, there is only one report from Sierra Leone that indicates data collected from the two approaches are integrated into the national IDSR system [110]. In some countries, the CBS Programme are still operating as pilot or research projects [112, 113], and most cover a limited geographical area and are mainly for specific disease programmes in rural settings [110].

One health surveillance

As part of an effective global response to diseases transmitted between animals and humans [114], there have been calls for integrating surveillance of zoonotic diseases in human and animal populations. The driving force is that about three-quarters of humans’ emerging infectious diseases have animal origin [115]. One health (OH) concept promotes the multi-sectoral collaboration between human, animal, and environmental health disciplines and sectors in addressing complex health issues [114]. Several African countries have carried out their prioritisation exercises on the zoonoses. Among the diseases that were ranked high include anthrax, brucellosis, viral haemorrhagic fevers, zoonotic avian influenza, human African trypanosomiasis, rabies and plague [116,117,118,119,120]. With this approach, OH surveillance is strongly encouraged at all levels to efficiently manage and coordinate health events involving humans, animals and their environment [16]. However, there are issues that need to be considered and addressed in the adoption of OH surveillance. These include the need to define the characteristics of OH surveillance and identify the appropriate mechanisms for inter-sectoral and multi-disciplinary collaboration [81, 116].

In 2019, the Tripartite organisations – the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the World Organisation for Animal Health, and the World Health Organization – developed the Tripartite Zoonoses Guide (TZG). The aim is to help the countries develop a capacity to address zoonoses in a coordinated manner, linking to existing international policies and frameworks and supporting efforts for global health security. The TZG includes three operational tools to support national authorities: (i) the Multi-sectoral Coordination Mechanism, (ii) the Joint Risk Assessment, and (iii) the Surveillance and Information Sharing operation tools [121].

Towards multi-sectoral and multi-indicator surveillance

The emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in Africa underline the urgent need to integrate public health surveillance systems [122]. As infectious disease threats increase in SSA, effective ways of predicting outbreaks and planning for outbreak responses become increasingly important. However, an epidemic intelligence that encompasses early warning functions for infectious diseases of humans and animals in SSA is almost non-existent. Therefore, we propose the development and adoption of a national platform for public health surveillance that is a multi-sectoral, multi-disease and multi-indicator epidemic intelligence system (Fig. 2). The system is envisaged to consolidate information from existing surveillance systems to define composite surveillance indicators with intelligence to trigger and guide unified responses to public health threats across sectors and diseases that share common risks. In One Health perspective, such a system may reduce the hurdle of monitoring enormous sector-specific and single-disease indicators, strengthen multi-sectoral collaboration, improve data quality and ultimately IDSR performance. For its operationalisation, a multi-sectoral coordination mechanism with representatives from the sectoral ministries should be established with timely-defined rotational leadership between the sectors responsible for human, animal and environmental health.

The importance of using both formal and informal data sources for timely and accurate infectious disease outbreak surveillance has been emphasized [86]. Evidence-based outbreak preparedness provides ground to streamline and concentrate efforts towards diseases that have been documented to circulate. Among other things, outbreak preparedness entails predicting possible epidemics with regards to the possible location of involvement, the risk and vulnerability of the population, the extent of the outbreak, its spread and socioeconomic consequences. Therefore, for any effective outbreak preparedness plan, information on prior risks is crucial in setting robust outbreak management and response plans. Research findings for decades have displayed mapping of exposure patterns and the burden of infectious diseases that can cause outbreaks in the community [5].

Modern technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning are widely applied in analysing a significant volume of data to assess the status and forecast future dynamics of diseases [123, 124]. A number of prediction models have been developed to provide event prediction, special ecological niche, diagnostic or clinical, spread or response information. The prediction models are valuable for disease prevention and saving disability-adjusted life years [125]. They also save valuable financial resources due to the high costs and resource utilisation associated with traditional surveillance systems. These emerging technologies are likely to become powerful means of facilitating the collection of more accurate and timely information, leading to information-based evidence. The techniques are expected to allow decision-makers to identify areas where the model predicts a particular risk category with certainty to effectively target limited resources to those areas most at risk for a given season.

Conclusion

This review indicates that most countries in SSA rely mainly on traditional indicator-based disease surveillance utilising data from healthcare facilities with limited use of data from other sources. However, the traditional indicator-based disease surveillance approaches face several challenges, including data quality and inefficient early warning systems, because they are less sensitive than event-based surveillance approaches. They most often miss information from populations who do not access health care or do so through informal channels, thus unable to detect new, potentially high-impact disease outbreaks. Moreover, there is a dearth of information on IDSR data quality, analyses that utilise advanced methodologies and use in the detection and response of infectious disease outbreaks in the region. Over the years, data-use and data-process have not been given adequate attention. This analysis indicates that future efforts to address disease surveillance systems should consider data quality, multi-source data analysis and triangulation, data use and data integration. Capacity building for health workers at the national and sub-national levels in data management is critical.

This review highlights the untapped opportunities for integrating community-based, digital surveillance through a one health approach that could improve public health surveillance in SSA. It is high time that the region explores and adopts the integration of several surveillance programmes into hybrid systems that combine traditional surveillance data with data from the public health laboratories, community, research settings, search queries, social media posts, and crowdsourcing. Improved performance requires the merging of current gains, strong collaboration from all stakeholders, supervision and regular evaluation of the surveillance system to identify and address challenges as they emerge. The introduction of innovative ways to further strengthen the surveillance and response system in SSA countries is critical to enhancing early detection and reporting of suspected cases of priority diseases, conditions and events.

To address the challenges of the IDSR system, there is a need to develop an electronic platform that will combine data from multiple relevant databases such as HMIS, research programmes, laboratory management information systems (LMIS), population-based surveys, digital disease surveillance, sentinel surveillance, OH surveillance and community-based surveillance initiatives to allow their interoperability. The aim is to make optimal use of community, facility and research-based epidemiological information in preparing the community to act before a health emergency happens, as well as to provide high-quality evidence to guide policy development and resource allocation at the national level. With this platform, a continuing analysis and review of scientific publications, social media, routine health data and demographic statistics can be established to feed different decision-making units. Composite and multi-sourced indicators that comprise information from various sources can be generated, analysed and monitored. The goal is to make data readily available and help speed up dissecting the information and putting programmes in place to detect and promptly respond to epidemics. The platform will foster improved utilisation of surveillance data for action and avoid delays in response to emergencies by linking health indicators with other information such as climate data that can add value to inform health risks accurately. A multi-sectoral approach should be used to pursue a common strategic goal of developing a workforce that can support public health surveillance and response.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article. No data are stored in a repository. No unpublished data are available following this review.

Abbreviations

- CBS:

-

Community-based Surveillance

- CDC:

-

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

- DDS:

-

Digital disease surveillance

- DHIS:

-

District Health Information System

- HIS:

-

Health Information Systems

- HMIS:

-

Health Management Information System

- ICT:

-

Information and Communication Technology

- IDS:

-

Integrated Disease Surveillance

- IDSR:

-

Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response

- OH:

-

One Health

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols

- SMS:

-

Short Message Service

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- USSD:

-

Unstructured Supplementary Service Data

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Fenollar F, Mediannikov O. Emerging infectious diseases in Africa in the 21st century. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;26:S10–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2018.09.004.

Talisuna AO, Okiro EA, Yahaya AA, Stephen M, Bonkoungou B, Musa EO, et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of infectious disease epidemics, disasters and other potential public health emergencies in the World Health Organisation Africa region, 2016–2018. Glob Health. 2020;16:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-050-4.

Perry H, Dhillon R, Liu A, Chitnis K, Panjabi R, Palazuelos D, et al. Community health worker programmes after the 2013–2016 Ebola outbreak. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(7):551-553.9. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.164020.

Maganga GD, Kapetshi J, Berthet N, KebelaIlunga B, Kabange F, et al. Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. New Engl J Med. 2014;371(22):2083–91. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411099.

Saker L, Lee K, Cannito B, Gilmore A, Campbell-Lendrum D. Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages. UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR), TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2. 2004. https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/.

Rugarabamu S, Mboera LEG, Rweyemamu MM, Mwanyika G, Lutwama J, et al. Forty-two years of responding to Ebola virus outbreaks in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e001955. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001955.

Rweyemamu M, Otim-Nape W, Serwadda D. Foresight. Infectious diseases: preparing for the future Africa. London: Office of Science and Innovation; 2006.

Tambo E, Ugwu EC, Ngogang JY. Need of surveillance response systems to combat Ebola outbreaks and other emerging infectious diseases in African countries. Infect Dis Poverty. 2014;3(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9957-3-29.

World Health Organization: Regional Office for Africa: Resolution AFR/RC 48/R2 of 2 1998.

Mandyata CB, Olowski LK, Mutale W. Challenges of implementing the integrated disease surveillance and response strategy in Zambia: A health worker perspective. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4791-9.

Kasolo F, Yoti Z, Bakyaita N, Gaturuku P, Katz R, Fischer JE, et al. IDSR as a platform for implementing IHR in African countries. Biosecur Bioterror. 2013;11(3):163–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2013.0032.

Buehler JW, Hopkins RS, Overhage JM, Sosin DM, Tong V, CDC Working Group. Framework for evaluating public health surveillance systems for early detection of outbreaks. Recommendations from the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Working Group. MMWR. 2004;53:1–11.

WHO. Technical guidelines for integrated disease surveillance and response in the African Region. Geneva and Atlanta: WHO and CDC; 2010. Available from: https://afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/IDSR_Technica_Guidelines_Final_2010_0.pdf.

Fall IS, Rajatonirina S, Yahaya AA, Zabulon Y, Nsubuga P, Nanyunja M, et al. Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) strategy: current status, challenges and perspectives for the future in Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(4):e001427. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001427.

Nsubuga P, Brown WG, Groseclose SL, Ahadzie L, Talisuna P, Mmbuji P, et al. Implementing integrated disease surveillance and response: Four African countries’ experience, 1998–2005. Glob Public Health. 2010;5(4):364–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690903334943.

Perry HN, McDonnell SM, Alemu W, Nsubuga P, Chungong S, Otten MW Jr, et al. Planning an integrated disease surveillance and response system: a matrix of skills and activities. BMC Med. 2007;5:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-5-24.

WHO. Technical guidelines for integrated disease surveillance and response in the World Health Organization African Region. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P ) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Sow I, Alemu W, Nanyunja M, Duale S, Perry HN, Gaturuku P. Trained district health personnel and the performance of integrated disease surveillance in the WHO African Region. East Afr J Public Health. 2010;7(1):16–9. https://doi.org/10.4314/eajph.v7i1.64671.

Cáceres VM, Sidibe S, Andre M, Traicoff D, Lambert S, King ME, et al. Surveillance training for ebola preparedness in Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, and Mali. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(13). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170299.

Mandja BM, Bompangue D, Handschumacher P, Ganzalez J-P, Salem G, Muyembe J-J, et al. The score of integrated disease surveillance and response adequacy (SIA): a pragmatic score for comparing weekly reported diseases based on a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:624. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6954-3.

Alemu T, Gutema H, Legesse S, Nigussie T, Yenew Y, Gashe K. Evaluation of public health surveillance system performance in Dangila district, Northwest Ethiopia: a concurrent embedded mixed quantitative/qualitative facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1343. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7724-y.

Begashaw B, Tesfaye T. Assessment of integrated disease surveillance and response implementation in special health facilities of Dawuro Zone. J Anesthesiol. 2016;4(3):11–5. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ja.20160403.11.

Adokiya MN, Awoonor-Williams JK, Barau IY, Beiersmann C, Mueller O. Evaluation of the integrated disease surveillance and response system for infectious diseases control in northern Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1397-y.

Adokiya MN, Awoonor-Williams JK, Beiersmann C, Müller O. The integrated disease surveillance and response system in northern Ghana: challenges to the core and support functions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:288. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0960-7.

Adokiya MN, Awoonor-Williams JK, Beiersmann C, Müller O. Evaluation of the reporting completeness and timeliness of the integrated disease surveillance and response system in northern Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2016;50(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v50i1.1.

Issah K, Nartey K, Amoah R, Bachan EG, Aleeba J, Yeetey E, et al. Assessment of the usefulness of integrated disease surveillance and response on suspected Ebola cases in the Brong Ahafo Region. Ghana Infect Dis Poverty. 2015;4:17.

Hemingway-Foday JJ, Souare O, Diallo BI, Bah M, Kaba AK, et al. Improving integrated disease surveillance and response capacity in Guinea, 2015–2018. Online J Public Health Inform. 2019;11(1). https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v11i1.9837.

Collins D, Rhea S, Diallo BI, Bah MB, Yattara F, Keleba RG, et al. Surveillance system assessment in Guinea: Training needed to strengthen data quality and analysis, 2016. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234796.

Mwatondo AJ, Ng’ang’a Z, Maina C, Makayotto L, Mwangi M, Njeru I, et al. Factors associated with adequate weekly reporting for disease surveillance data among health facilities in Nairobi County, Kenya, 2013. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23:165. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.23.165.8758.

Nakiire L, Masiira B, Kihembo C, Katushabe E, Natseri N, Nabukenya I, et al. Healthcare workers’ experiences regarding scaling up of training on integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) in Uganda, 2016: cross sectional qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3923-6.

Nagbe T, Yealue K, Yeabah T, Rude JM, Fallah M, Skrip L, Agbo C, et al. Integrated disease surveillance and response implementation in Liberia, findings from a data quality audit, 2017. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33(Supp 2):10. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2019.33.2.17608.

Randriamiarana R, Raminosoa G, Vonjitsara N, Randrianasolo R, Halm A, et al. Evaluation of the reinforced integrated disease surveillance and response strategy using short message service data transmission in two southern regions of Madagascar, 2014–15. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3081-2.

Wu JT-S, Kagoli M, Kaasbøll JJ, Bjune GA. Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) in Malawi: Implementation gaps and challenges for timely alert. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200858.

Ibrahim LM, Stephen M, Okudo I, Kitgakka SM, Mamadu IN, Njai IF, et al. A rapid assessment of the implementation of integrated disease surveillance and response system in Northeast Nigeria, 2017. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08707-4.

Jinadu KA, Adebiyi AO, Sekoni OO, Bamgboye EA. Integrated disease surveillance and response strategy for epidemic prone diseases at the primary health care (PHC) level in Oyo State, Nigeria: What do health care workers know and feel? Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31:19. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.31.19.15828.

Nnebue CC, Onwasigwwe CN, Adogu PO, Adinma ED. Challenges of data collection and disease notification in Anambra State, Nigeria. Trop J Med Res. 2014;17(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-0388.130173.

Motilewa O, Akwaowo CD, Ekanem AM. Assessment of implementation of integrated disease surveillance and response in Akwaibom State Nigeria. Ibom Med J. 2015;8(1):24–5.

Thierry N, Kabeja A, Asiimwe A, Binagwaho A, Koama JB, Johnson P, et al. A national electronic system for disease surveillance in Rwanda (eIDSR): Lessons learned from a successful implementation. Online J Public Health Inform. 2014;6(1). https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v6i1.5014.

Njuguna C, Jambai A, Chimbaru A, Nordstrom A, Conteh R, Latt A, et al. Revitalization of integrated disease surveillance and response in Sierra Leone post Ebola virus disease outbreak. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:364. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6636-1.

Sahal N, Reintjes R, Eltayeb EM, Aro AR. Assessment of core activities and supportive functions for the communicable diseases surveillance system in Khartoum state, Sudan, 2005–2007. E Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(12):1204–10. https://doi.org/10.26719/2010.16.12.1204.

Mboera LEG, Rumisha SF, Magesa SM, Kitua AY. (2001) Utilisation of health management information system in disease surveillance in Tanzania. Tanzania Health Res Bull. 2001;3(2):15–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v3i2.14213.

Mboera LEG, Rumisha SF, Mlacha T, Mayala BK, Bwana VM, Shayo EH. Malaria surveillance and use of evidence in planning and decision making in Kilosa District, Tanzania. Tanzania J Health Res. 2017;19(3). https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v19i3.7.

Mghamba JM, Mboera LEG, Krekamoo W, Senkoro KP, Rumisha SF, Shayo EH, et al. Challenges of implementing integrated disease surveillance and response strategy using the current health management information system in Tanzania. Tanzania Health Res Bull. 2004;6:57–63. https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v6i2.14243.

Nsubuga P, Eseko N, Wuhib T, Ndayimirije N, Chungong S, McNabb S. Structure and performance of infectious disease surveillance and response, United Republic of Tanzania, 1998. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:196–203. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0042-96862002000300005.

Rumisha SF, Mboera LEG, Senkoro SF, Gueye D, Mmbuji PL. Monitoring and evaluation of Integrated disease surveillance and response in selected districts in Tanzania. Tanzania Health Res Bull. 2007;9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v9i1.14285.

Pascoe L, Lungo J, Kaasbøll J, Kileleni I. Collecting integrated disease surveillance and response data through mobile phones. ISTAfrica 2012 Conference Proceedings. Paul Cunningham and Miriam Cunningham (Eds). IIMC Int Inf Manage Corporation. 2012;34–2.

Mboera LEG, Sindato C, Mremi IR, George J, Ngolongolo R, Rumisha SF, et al. Socio-ecological systems analysis and health system readiness in responding to dengue epidemics in Ilala and Kinondoni districts, Tanzania. Front Pubic Health. 2021; (in press).

Franco LM, Setzer J, Banke K. Improving performance of IDSR at district and facility levels: experiences in Tanzania and Ghana in making IDSR operational; 2006.

Kihembo C, Masiira B, Nakiire L, Katushabe E, Natseri N, Nabukenya I, et al. The design and implementation of the re-vitalised integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) in Uganda, 2013–2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5755-4.

Lukwago L, Nanyunja M, Ndayimirije N, Wamala J, Malimbo M, Mbabazi W, et al. The implementation of integrated disease surveillance and response in Uganda: a review of progress and challenges between 2001 and 2007. Health Policy Plan. 2012;28:30–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs022.

Masiira B, Nakiiere L, Kihembo C, Katushabe E, Natseri N, Nabukenya I, et al. Evaluation of integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) core and support functions after the revitalisation of IDSR in Uganda from 2012 to 2016. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6336-2.

Wamala JF, Okot C, Makumbi I, Natseri N, Kisakye A, Nanyunja M, et al. Assessment of core capacities for the International Health Regulations (IHR [2005]) – Uganda, 2009. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(Suppl 1):S9 https://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/S1/59.

Haakonde T, Lingenda G, Munsaje F, Chishimba K. Assessment of factors affecting the implementation of the integrated disease surveillance and response in public health care facilities - the case of Rufunsa District, Zambia. Divers Equal Health Care. 2018;15(1):15–22. https://doi.org/10.21767/2049-5471.1000123.

Kooma EK. Assessment of the integrated disease surveillance and response implementation in selected health facilities of Southern Province of Zambia. Int J Adv Res. 2019;7(4):961–76. https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/8914.

Wolfe CM, Hamblion EL, Dzotsi EK, Mboussou F, Eckerle I, Flahault A, et al. Systematic review of Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) implementation in the African region. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0245457. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245457.

Mwengee W, Okeibunor J, Poy A, Shaba K, Kinuani LM, Minkoulou E, et al. Polio eradication initiative: Contribution to improved communicable diseases surveillance in WHO African region. Vaccine. 2016;34(43):5170–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.060.

Maïga A, Jiwani SS, Mutua MK, Porth TA, Taylor CM, Asiki G, et al. Countdown to 2030 collaboration for Eastern and Southern Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001849.

Ahanhanzo YG, Ouendo E-M, Kpozèhouen A, Levêque A, Makoutodé M, Dramaix-Wilmet M. Data quality assessment in the routine health information system: an application of the lot quality assurance sampling in Benin. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(7):837–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu067.

Rumisha SF, Lyimo EP, Mremi IR, Tungu PK, Mwingira VS, Mbata D, et al. Data quality of the routine health management information system at the primary healthcare facility and district levels in Tanzania. BMC Med Inform Decis. 2020;20:340. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01366-w.

Gimbel S, Micek M, Lambdin B, Lara J, Karagianis M, Cuembelo F, et al. An assessment of routine primary care health information system data quality in Sofala Province, Mozambique. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-9-12.

Amoakoh-Coleman M, Kayode GA, Brown-Davies C, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K, et al. Completeness and accuracy of data transfer of routine maternal health services data in the greater Accra region. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1058-3.

Kasambara A, Kumwenda S, Kalulu K, Lungu K, Beattie T, Masangwi S, et al. Assessment of implementation of the health management information system at the district level in southern Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2017;29(3):240–6. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v29i3.3.

Bhattacharya AA, Umar N, Audu A, Felix H, Allen E, Schellenberg JRM, et al. Quality of routine facility data for monitoring priority maternal and newborn indicators in DHIS2: a case study from Gombe State, Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211265.

Dehnavieh R, Haghdoost A, Khosravi A, Hoseinabadi F, Rahimi H, et al. The District Health Information System (DHIS2): a literature review and metasynthesis of its strengths and operational challenges based on the experiences of 11 countries. Health Inf Manag J. 2019;48(2):62–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358318777713.

Nkengasong JN, Nsubuga P, Nwanyanwu O, et al. Laboratory systems and services are critical in the global health: time to end the neglect? Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(3):368–73. https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCPMPSINQ9BRMU6.

Onyebujoh PC, Thirumala AK, Ndihokubwayo J-B. Integrating laboratory networks, surveillance systems and public health institutes in Africa. Afr J Lab Med. 2016;5(3):a431. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajlm.v5i3.431.

Buckee CO, Cardenas MIE, Corpuz J, Ghosh A, Haque F, Karim J, et al. Productive disruption: opportunities and challenges for innovation in infectious disease surveillance. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;3:e000538. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-00053.

Simba DO, Kakoko DC, Warsame M, Premji Z, Gomez MF, Tomson G, et al. Understanding caretakers’ dilemma in deciding whether or not to adhere with referral advice after pre-referral treatment with rectal artesunate. Malar J. 2010;9:123. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-123.

Ngugi AK, Agoi F, Mahoney MR, Lakhani A, Mang’ong’o D, Nderitu E, et al. Utilization of health services in a resource-limited rural area in Kenya: Prevalence and associated household-level factors. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172728.

Zyaambo C, Siziya S, Fylkesnes K. Health status and socio-economic factors associated with health facility utilization in rural and urban areas in Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:389. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-389.

Assefa T, Belachew T, Tegegn A, Deribew A. Mothers’ health care seeking behaviour for childhood illnesses in Derra District, Northshoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2008;18(3):87–94.

Nsubuga P, Nwanyanwu O, Nkengasong JN, Mukanga D, Trostle M. Strengthening public health surveillance and response using the health systems strengthening agenda in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:S5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-S1-S5.

Mbondji PE, Kabede D, Soumbey-Alley EW, Zielinski C, Kouvividila W, Lusamba-Dikassa P-S. Health information systems in Africa: descriptive analysis of data sources, information products and health statistics. J Roy Soc Med. 2014;107(1S):34–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107681453.

Teklegiorgis K, Tadesse K, Mirutse G, Terefe W. Level of data quality from Health Management Information Systems in a resources limited setting and its associated factors, eastern Ethiopia. S Afr J Inf Manag. 2016;18(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v18i1.612.

Awunor NS, Omuemu VO, Adam VY. Knowledge and practice of disease surveillance and notification among resident doctors in a tertiary health institution in Benin City: implications for health systems strengthening. J Comm Med Prim Health Care. 2014;26(2):107–15.

Toda M, Zurovac D, Njeru I, Kareko D, Mwau M, Morita K. Health worker knowledge of integrated disease surveillance and response standard case definitions: a cross-sectional survey at rural health facilities in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5028-2.

Mutale W, Chintu N, Amoroso C, Awoonor-Williams K, Phillips J, Baynes C, et al. Improving health information systems for decision making across five sub-Saharan African countries: implementation strategies from African Health Initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(Suppl. 2):59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-S2-S9.

Steele L, Orefuwa E, Dickmann P. Drivers of earlier infectious disease outbreak detection: a systematic literature review. Int J Inf Dis. 2016;53:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.0005.

Smith M, Madon S, Anifalaje A, Lazaro-Malecela M, Michael E. Integrated health information systems in Tanzania: Experience and challenges. Electr J Inform Syst Devel Count. 2008;33(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2008.tb00227.x.

George J, Häsler B, Mremi IR, Sindato C, Mboera LEG, Rweyemamu MM, et al. Integration mechanisms in human and animal health surveillance systems: challenges and opportunities in addressing global health security threats: A systematic review. One Health Outlook. 2020;2:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-020-00017-4.

Ilesanmi OS, Babasola OM. Clinician sensitization on integrated disease surveillance and response in Federal Medical Centre Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria, 2016. Public Health Indon. 2017;3(2).

Mathers CD, Fat M, Inoue M, Rao C, Lopez A. Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;2005(83):171–7.

Hay SI, George DB, Moyes CL, Brownstein JS. Big data opportunities for global infectious disease surveillance. PLoS Med. 10:e1001413. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001413.

Disease Surveillance, Emergency Preparedness, and Outbreak Response in Eastern and Southern Africa: a situational assessment and five-year action plan for the Africa CDC Strengthening Regional Public Health Institutions and Capacity for Surveillance and Response Program 18 March 2021. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/3052716160/.

O’Shea J. Digital disease detection: A systematic review of event-based internet biosurveillance systems. Int J Med Inform. 2017;101:15–22.

Chretien J-P, Lewis SH. Electronic public health surveillance in developing settings: meeting summary. BMC Proceed. 2008;2(Suppl 3):S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-6561-2-s3-s1.

Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan. Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3151.

Ferretti L, Wymant C, Kendall M, Zhao L, Nurtay A, Abeler-Dörner D, et al. Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 transmission suggests epidemic control with digital contact tracing. Science. 2020;368(6491):eabb6936. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb6936.

Eysenbach G. SARS and population health technology. J Medical Int Res. 2003;5:e14. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5.2.e14.

Tom-Aba D, Nguku P, Arinze C, Krause G. Assessing the concepts and designs of 58 mobile apps for the management of the 2014–2015 West Africa Ebola outbreak: systematic review. JMIR Public Health Surv. 2018;4:e68. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.9015.

Alwashmi MF. The use of digital health in the detection and management of COVID-19. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2906. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082906.

Fähnrich C, Denecke K, Adeoye OO, Benzler J, Claus H, Kirchner G, Mall S, Richter R, Schapranow MP, Schwarz NG, Tom-Aba D, Uflacker M, Poggensee G, Krause G. Surveillance and Outbreak Response Management System (SORMAS) to support the control of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(12):2109071. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.12.21071.

Perscheid C, Benzler J, Hermann C, Janke M, Moyer D, Laedtke T, et al. Ebola outbreak containment: real-time task and resource coordination with SORMAS. Front ICT. 2018;5:7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fict.2018.00007.

Adeoye O, Tom-Aba D, Ameh C, Ojo O, Ilori E, Gidado S, et al. Implementing Surveillance and Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS) for public health in west Africa- lessons learnt and future direction. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2017;22(2):1–17. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijtdh/2017/31584.

Yavlinsky A, Lule SA, Burns R, Zumla A, McHugh TD, Ntoumi F, et al. Mobile-based and open-source case detection and infectious disease outbreak management systems: a review. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:37.

African Union. 2020. https://africacdc.org/programme/surveillance-disease-intelligence/digital-disease-surveillance/.

Morse SS, Rosenberg BH, Woodall J. ProMED global monitoring of emerging diseases: design for a demonstration program. Health Policy. 1996;38:135–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(96)00863-9.

Freifeld CC, Mandl KD, Reis BY, Brownstein JS. HealthMap: global infectious disease monitoring through automated classification and visualization of internet media reports. J Am Med Inform Assn. 2008;15(2):150–7. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M2544.

Ratnayake R, Crowe SJ, Jasperse J, Privette G, Stone E, Miller L, et al. Assessment of community event-based surveillance for Ebola virus disease, Sierra Leone, 2015. Emerg Inf Dis. 2016;22(8):1431-1437.4. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2208.160205.

Technical Contribution to the June 2018 WHO meeting. A definition for community-based surveillance and a way forward: results of the WHO global technical meeting, France, 26 to 28 June 2018. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(2):1800681. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560.7917.ES.2019.24.2.1800681.

Kuehnel A, Keating P, Polonsky J, Haskew C, Schenkel K, de Waroux OL, et al. Event-based surveillance at health facility and community level in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(1):e001878. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001878.

Ndiaye SM, Quick L, Sanda O, Niandou S. The value of community participation in disease surveillance: a case study from Niger. Health Promot Int. 2003;18:89–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/18.2.89.

Azhar M, Lubis AS, Siregar ES, Alders RG, Brum E, McGrane J, et al. Participatory disease surveillance and response in Indonesia: strengthening veterinary services and empowering communities to prevent and control highly pathogenic avian influenza. Avian Dis. 2010;54(1 Suppl):749–53. https://doi.org/10.1637/8713-031809-Reg.1.

Marquet RL, Bartelds AIM, Van Noort SP, Koppeschaar CE, et al. Internet-based monitoring of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the general population of the Netherlands during the 2003–2004 influenza season. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:242. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-242.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). Community-based surveillance: guiding principles. Geneva: IFRC; 2017. Available from: https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/document/community-based-surveillance-guiding-principles/.

Wójcik OP, Brownstein JS, Chunara R, Johansson MA. Public health for the people: participatory infectious disease surveillance in the digital age. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2014;11:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-7622-11-7.

Brooks-Pollock E, Tilston N, Edmunds WJ, Eames KTD. Using an online survey of healthcare-seeking behaviour to estimate the magnitude and severity of the 2009 H1N1v influenza epidemic in England. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-68.

Stone E, Miller L, Jasperse J, Privette G, Beltran JCD, Jambai A, et al. Community event-based surveillance for Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone: implementation of a national-level system during a crisis. PLoS Curr. 2016;8:ecurrents.outbreaks.d119c71125b5cce312b9700d744c56d8.

Clara A, Ndiaye SM, Joseph B, Nzogu MA, Coulibaly D, Alroy KA, et al. Community-Based Surveillance in Côte d'Ivoire. Health Secur. 2020;18(S1):23–33. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2019.0062.

Clara A, Do TT, Dao ATP, Tran PD, Dang TQ, Tran QD, et al. Event-based surveillance at community and healthcare facilities, Vietnam, 2016–2017. Emerg Inf Dis. 2018;24(9):1649-1658.10. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2409.171851.

Karimuribo ED, Mutagahywa E, Sindato C, Mboera L, Mwabukusi M, Kariuki Njenga M, et al. A smartphone app AfyaData for innovative one health disease surveillance from community to national levels in Africa: intervention in disease surveillance. JMIR Pub Health Surveill. 2017;3(4):e94. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.7373http://publichealth.jmir.org/2017/4/e94/.

N’Guessan S, Attiey HB, Ndiaye S, Diarrassouba M, McLain G, Shamamba L, et al. Community-based surveillance: A pilot experiment in the Kabadougou-Bafing-Folon health region in Côte d´Ivoire. J Int Epidemiol Public Health. 2019;2:11 https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/article/2/11/full.

Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging infectious diseases: Threats to human health and global stability. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(7):e1003467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003467.

Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536.

Bordier M, Uea-Anuwong T, Binot A, Hendrikx P, Goutard FL. Characteristics of one health surveillance systems: A systematic literature review. Prev Vet Med. 2018;S0167–5877(18)30365–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.10.005.

Munyua P, Bitek A, Osoro E, Pieracci EG, Muema J, Mwatondo A, et al. Prioritization of zoonotic diseases in Kenya, 2015. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161576.

Ohene S-A. Experiences with JEE and impact on rabies programmes. World Health Organization Ghana Country Office, 2017. https://rabiesalliance.org/resource/sally-oheneghana-jee-rabies-programparacon-2018.

Semakatte M, Krishnasamy V, Bulage L, Nantima N, Monje F, Ndumu D, et al. Multisectoral prioritization of zoonotic diseases in Uganda, 2017: A One Health perspective. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196799.

Stolka KB, Ngoyi BF, Grimes KE, Hemingway-Foday JJ, Lubula L, Magazani AN, et al. Assessing the surveillance system for priority zoonotic diseases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2017. Health Secur. 2018;16(S1). https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2018.0060.

Joint Risk Assessment Operational Tool (JRA OT) An operational tool of the tripartite zoonoses guide taking a multisectoral, one health approach: a tripartite guide to addressing zoonotic diseases in countries. Available: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Media_Center/docs/pdf/onehealthportal/EN_JointRiskAssessmentOperationalTool_webversion.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2021.

Onyebujoh PC, Thirumala AK, Ndihokubwayo J-B. Integrating laboratory networks, surveillance systems and public health institutes in Africa. Afr J Lab Med. 2016;5(3):a431. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajlm.v5i3.431.

Lowe R, Bailey TC, Stephenson DB, Jupp TE, et al. The development of an early warning system for climate-sensitive disease risk with a focus on dengue epidemics in Southeast Brazil. Stat Med. 2013;32:864–83.

Agrebi S, Larbi A. Use of artificial intelligence in infectious diseases. Artificial Intelligence in Precision Health, Chapter 18, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817133-2.00018-5.

Yang L-P, Liang S-Y, Wang X-J, Li X-J, Wu Y-L, Ma W. Burden of disease measured by disability-adjusted life years and a disease forecasting time series model of scrub typhus in Laiwu, China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(1):e3420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003420.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sokoine University of Agriculture's One Health Sciences Community of Practice members for their support and contribution during the earlier development of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has not received any project-specific funding. IRM and JG are PhD students supported by the World Bank and Government of the United Republic of Tanzania Scholarship through SACIDS Foundation for One Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the review. IRM led data acquisition and analysis, with SFR, CS and LEGM responsible for the interpretation. IRM and JG drafted the work, SIK and LEGM supervised all stages of the review and contributed to the manuscript’s writing. IRM, LEGM and SFR provided substantial revisions. Both authors revised and approved the final version of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or conduct of the study.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mremi, I.R., George, J., Rumisha, S.F. et al. Twenty years of integrated disease surveillance and response in Sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities for effective management of infectious disease epidemics. One Health Outlook 3, 22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-021-00052-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-021-00052-9