Abstract

Background

Wildland firefighters are likely to experience heightened risks to safety, health, and overall well-being as changing climates increase the frequency and intensity of exposure to natural hazards. Working at the intersection of natural resource management and emergency response, wildland firefighters have multidimensional careers that often incorporate elements from disparate fields to accomplish the tasks of suppressing and preventing wildfires. Thus, they have distinctly different job duties than other firefighters (e.g., structural firefighters) and experience environmental health risks that are unique to their work. We conducted a systematic scoping review of scientific literature that addresses wildland firefighter environmental health. Our goal was to identify studies that specifically addressed wildland firefighters (as opposed to firefighters in a broader sense), geographic and demographic trends, sample sizes, patterns in analysis, and common categories of research.

Results

Most studies have clustered in a few highly developed countries, and in the United States within California and Idaho. Many studies fail to consider the impact that demographic factors may have on their results. The number of studies published annually is increasing and themes are broadening to include social and psychological topics; however, most authors in the field have published an average of < 3 articles.

Conclusions

We identify three areas that we believe are imminent priorities for researchers and policymakers, including a lack of diversity in study geography and demography, a need for more complex and interactive analyses of exposure, and prioritization of wildland firefighters in research funding and focus.

Resumen

Antecedentes

Los combatientes de incendios probablemente experimentan elevados riesgos en la salud, la seguridad, y en el estado de bienestar general a medida que los climas cambiantes incrementan la frecuencia e intensidad de exposición a los peligros naturales. Trabajando en la intersección entre el manejo de los recursos naturales y la respuesta a la emergencia, los combatientes de incendios tienen carreras multidimensionales que frecuentemente incorporan elementos de distintos campos para lograr completar las tareas de suprimir y prevenir incendios de vegetación. De esa manera, ellos tienen tareas distintivamente diferentes que otros bomberos (p. ej. bomberos estructurales) y experimentan riesgos ambientales en su salud que son únicos en sus trabajos. Condujimos un trabajo de naturaleza sistémica de revisión bibliográfica que se enfocó en la salud ambiental de los brigadistas de incendios de vegetación. Nuestro objetivo fue identificar estudios que específicamente se enfoquen en brigadistas de incendios de vegetación (en contraposición con otros bomberos en un sentido amplio, las tendencias geográficas y demográficas, el tamaño de las muestras, patrones de análisis, y categorías comunes de investigación.

Resultados

La mayoría de los estudios se han agrupado en pocos países muy desarrollados, y dentro de los EEUU en California y Idaho. Muchos estudios fallaron en considerar el impacto que los factores demográficos podrían tener en sus resultados. El número de estudios anualmente se está incrementando y los temas ampliándose, incluyendo tópicos sociales y psicológicos; de todas maneras, la mayoría de los autores en esa especialidad han publicado un promedio < 3 artículos.

Conclusiones

Identificamos tres áreas que creemos son inminentes prioridades para investigadores y decisores políticos, incluyendo una falta de diversidad en estudiar geografía y demografía, la necesidad de realizar un análisis más completo e interactivo de la exposición, y la priorización de los brigadistas en cuanto a fondos para investigación y su enfoque.

Similar content being viewed by others

Context and background

Broadly, environmental health considers existing and potential hazards, access and equity in provisioning care and resources, and exposure incurred in an environment (Huber et al. 2011). As our global environment shifts with changing climates, environmental health impacts will be inequitably distributed among professions and geographic locations. Wildland firefighters, due to the nature of their work, are likely to see significantly increased environmental health risks as both hazards and their exposure increase due to the increased frequency and intensity of wildfires (Podur & Wotton 2010). Thus, wildland firefighter environmental health scientists are faced with an imminent challenge. They must necessarily create interdisciplinary solutions, relying on concepts from medical, occupational, environmental, and sociological fields to infer the conditions and state of the wildland firefighting workforce; in tandem, they must also identify the contributing factors that may promote or detract from the overall health and well-being of said population to rapidly address these looming issues (Huby & Adams 2009; Huber et al. 2011; Brown 2013).

Wildland firefighting is often considered a subfield of a broadly- or diffusely defined field of “firefighting” due to the smoke, flame, and heat exposure sustained by workers. Firefighting is included even more broadly as part of emergency management and disaster response, since workers in these fields are generally trained in incident command systems and can conduct interagency work that may include performing tasks that are not exclusive to fire suppression (e.g., traffic control and mitigation, evacuation, establishment of safety zones and shelters, VanDevanter et al. 2010; Thompson et al. 2018). While wildland firefighters may work in emergency management periodically and some commonalities with structural firefighting do exist, many of the occupational and environmental exposures and hazards that wildland firefighters face are distinctly different from other classes of emergency responders and firefighters. Here, we defined a wildland firefighter as per Ragland et al. (2023) as a person “who is tasked with preventing, actively suppressing, or supporting the active suppression of fires occurring in natural or naturalized vegetation” and included such job categories as operational wildland firefighters (e.g., engine crews, hand crews, hotshot crews, smokejumpers, rappelers), fire prevention, fuel management specialists, fire ecologists, fire planners, wildland fire dispatchers, fire cache managers, fire equipment operators, and fire aviation.

Wildland firefighters’ work is unique in the physiological, psychological, performance, and safety demands it imposes on its workers (Ruby et al. 2023): (1) They work in natural environments and are exposed to natural elements for extended periods of time, sometimes multiple days; (2) They often are working in remote settings, which can mean crews are socially isolated for prolonged periods; (3) Wildland fires are often sustained events with unpredictable shifts in intensity occurring in rugged terrain, so the physicality of the work requires burst energy combined with extended periods of high endurance and high impact activity; (4) Many wildland firefighters wear significantly less PPE than structural firefighters (e.g., minimal or no respiratory or airway protection), though they may endure more sustained and prolonged smoke exposure [average of 7–11.5 h (Reinhardt & Ottmar 2004) in contrast to < 11 min for 90% of structural fire incidents (Federal Emergency Management Agency 2006)]. This combination of exposure and physiological demands significantly alters the risk equation for injury, illness, and stress-related impacts on mental health and social interactions (Alfano et al. 2021).

Objectives and research questions

A study by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics found that wildland firefighters account for 25% of all firefighter fatalities despite being only about 2% of the total firefighting workforce in the USA: This was attributed to an increased likelihood of multi-casualty events because of a crew-based workforce (Clarke & Zak 1999). However, from 2007 to 2016, the top three causes of wildland firefighter death included heart attacks (24%), vehicle accidents (20%), and aircraft accidents (18%); entrapments were the fourth most common cause of death (PMS 841 2017). Despite this, wildland firefighter environmental health remains understudied relative to structural firefighting and other high-risk job fields (e.g., timber cutting, mining). Thus, this review is necessitated by a lack of scholarly consensus about potential occupational hazards to health, safety, and well-being of wildland firefighters. At present, we lack a comprehensive conceptual framework to address occupational hazards, and as a result, comparative research among studies is hampered.

Our research questions were as follows: (1) What is the scope of the wildland firefighter environmental health literature at present? (2) What categories do the existing literature fall into? and (3) What geographic locations and demographic groups are understudied in the field of wildland firefighter environmental health? We followed the review guidelines detailed in Peters et al. (2015) and Munn et al. (2018) to conduct this review (see PRISMA, Fig. 1).

Inclusion criteria

We included all studies that directly or indirectly assessed wildland firefighter health, well-being, and/or safety. We also included studies that assessed other biotic or abiotic parameters of wildland fires with the stated goal of examining wildland firefighter health, well-being, and/or safety. We excluded survey studies where wildland firefighters were less than 5% of the total study population, non-scientific studies (i.e., personal narratives), literature reviews, non-peer-reviewed materials (except theses and dissertations), and materials that mentioned wildland firefighters as a motivator for the study but did not address a question directly related to wildland firefighters (i.e., Riley et al. 2022). This review also included studies that addressed environmental health topics related to wildland firefighters but did not experiment directly with wildland firefighters or human subjects when the primary motivation for the study was to assess wildland firefighters (i.e., studies of wood smoke on non-human tissue with the goal of understanding impacts on wildland firefighter health). Further, we excluded studies that focused on communities impacted by wildfire, even when wildland firefighters were mentioned within, as the primary focus was outside the realm of this review.

Search criteria

We assembled literature with an exhaustive Google Scholar, ORCID, OVID Medline, Web of Science, JSTOR, and SCOPUS search using the terms “wildland firefighter,” “wildland firefighter environmental health,” “wildland firefighter health,” “wildland firefighter occupational health,” and “wildland firefighter mental health.” We supplemented this search with known literature previously acquired through other means. We acquired all literature in which the title or abstract explicitly mentioned or referenced: wildland firefighters, firefighter health, safety, well-being, recruitment, and/or retention. Papers were acquired directly from search engine sources or using the Missouri University of Science and Technology Interlibrary Loan (ILLiad) Department when complete versions were unavailable elsewhere. Digital complete versions of all papers were compiled in a Google drive accessible to all authors.

Extracting and charting results

All citations were entered in a .CSV file with basic information (authors, year, journal, volume, page numbers, category). We also recorded study location; study year; study length; total sample size; whether the study analyzed direct or indirect effects of fire on wildland firefighter health; whether the analysis considered age, gender, and ethnicity; and the summary findings of the study. We defined a direct effect as one that was directly attributable to a wildland fire or one that happened while on a wildland fire, whereas an indirect effect may have occurred secondary to or had a wildland fire as a contributing factor in its emergence but could not be causally linked to the fire itself.

We identified four primary conceptual categories, psychological/sociological, medical, occupational/safety, and performance, to which all studies were assigned. We assigned each included paper to a single category that best fits its theme. Categories were informed by a word cloud created from the titles of papers that met the criteria for study inclusion (Fig. 2). Within a category, we examined additional parameters as appropriate. Psychological and sociological studies were those that considered the impacts of wildland firefighting careers on mental health, mental well-being, community and peer-to-peer interactions, sleep, and behavioral stress responses. Medical studies were those that considered impacts of the career on physical health, physical well-being, physiology, anatomy, and/or longevity. We considered performance studies to be those that measured how physical, chemical, mental, or other environmental parameters changed wildland firefighters’ ability to complete tasks, tests, or other job metrics. Occupational and safety studies were defined as those that considered how worker safety, well-being, or health influenced work outcomes. Occupational and safety studies also included studies examining ways to increase worker safety and well-being, including improvements to PPE. Analyses were conducted from October 2022 to January 2023 and included literature published before January 2023.

Word cloud of publication titles that were analyzed for this study. Word size relates to frequency of occurrence. Themes related to traditional wildland fire values of performance, exposure, suppression, occupational health, and safety emerged as the most frequently used words. Culture, monitoring, comparison, training, methods, communication, and practices were much less frequently used in titles. Other important factors in environmental health such as well-being, mental health, co-worker interactions, demographic factors, and social support systems are absent

Results

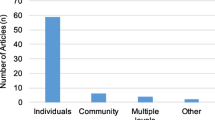

A total of 142 papers met requirements for inclusion in this review, within which we identified 376 total authors (Table 1). Individual authors published 1.51 papers on average (range 1–11). When we included only authors that had published more than one paper, the mean number of papers per author was 2.99. The median sample size across all studies was 35 individuals (quartile: 14.5–114.75). Studies were conducted primarily in highly developed countries and the western USA (Figs. 3 and 4) and focused on operational wildland firefighters (N = 141). Overall, the annual number of publications on wildland firefighter environmental health has steadily increased since the 1990s (Fig. 5). In addition to narrow geographic scopes, most studies analyzed few demographic variables (Fig. 6). Medical and occupational studies comprised a plurality of the articles we analyzed (41.4% and 39.3%, respectively).

Percentage of studies considering gender, ethnicity, or age directly in analyses by category. “All studies” is a category where the data are summated for all categories to allow visualization of trends in the entire set. Y axis = percentage of studies including a demographic variable of interest in their analysis. X axis = categorical variables. “Direct” indicates studies that assessed direct effects of wildland fires on wildland firefighter health, rather than studies that may have used correlative inference

Medical studies

We identified 59 studies that addressed medical topics in wildland firefighter environmental health. Of these, cardiovascular disease, and risk (N = 14, 23.7%), smoke and pulmonary and respiratory impacts (N = 12, 20.314%), and heat exposure (N = 10, 16.9%) were the most examined subjects. Median study size was 36.5 participants (quartile 11.5–105.75), and most studies took place in North America (N = 42) and Europe (N = 12). The longest study followed participants for three fire seasons (approximately 3 years). Four (6.8%) studies included ethnicity in their analyses; 26 (44.1%) included age, and 19 (32.2%) included gender. Studies were most often conducted as direct assessments of wildland fire impacts on health (N = 42, 71.2%). Overall, these studies attributed a suite of medical risks to wildland firefighter exposure to wood smoke, particulate matter, ash, soil, heat, and prolonged physiological stress. Short-term smoke inhalation effects were reported, but these effects appeared to dissipate rapidly (Dorman & Ritz 2014; Wu et al. 2021a, b); however, other studies found that 65% of career wildland firefighters complain of respiratory symptoms (Swiston et al. 2008), suggesting that long-term effects may exist, even if they are not readily apparent. While few COVID data exist for wildland firefighters, acute and chronic smoke exposure and dense crew housing may increase risk and vulnerability to infection and may make symptom-based pulmonary diagnoses more difficult (Metz et al. 2022).

Physical injury rates on the job for wildland firefighters were reported at 20% (Christison et al. 2021a, b; Garcia-Heras et al. 2022), and heat-related stress and injury risk were reported to be exacerbated by the personal protective equipment and packs (20.5 kg +) that wildland firefighters wear (Carballo-Leyenda et al. 2019). Common injury sites included the knees, low back, and shoulders, and 30% of all injuries were the result of a slip, trip, or fall (Moody et al. 2019). Fitness often was an important physiological indicator of muscle damage and short-term overuse, and higher levels of physical fitness were often an indicator of decreased risk for rhabdomyolysis (Christison et al. 2021a).

Medical incidents are the leading direct cause of wildland firefighter death in the USA (Butler et al. 2017), but substantial gaps exist in our understanding of both long- and short-term medical impacts of the physiological strain, environmental exposure, and additional risk factors incurred during wildfires and other portions of wildland firefighter careers. No studies consider the impacts of wildland firefighting on endocrine function, microbiomes, digestive function and nutrition, skin infection, vision and ocular systems, fertility, long-term neurological risks, cancer risk (except lung cancer, Navarro et al. 2019), or reproductive health or gestation. Further, studies of wildland firefighting-specific injury recovery and surgical outcomes are non-existent. These areas represent potential avenues of future exploration.

Psychological and sociological studies

We identified 11 studies of psychological and sociological factors in wildland firefighter environmental health. These studies were published between 2011 and 2022 and most addressed sleep (N = 5) and post-traumatic stress disorder (N = 2). Studies were conducted in North America (N = 6), Australia (N = 3), Europe (N = 1), and Israel (N = 1) and were generally single-survey, single-trial, or single-season events (N = 10, 90.1%). The longest study was 30 months in duration (Cherry et al. 2021). The median sample size was 37 participants (quartile 11–102). Over half of the studies utilized surveys (N = 6, 54.5%); other common techniques were interviews (N = 5, 45.5%) and experimental trials (N = 3, 27.3%). Nine (81.8%) studies considered indirect effects of wildland fire careers, whereas two (18.2%, both addressing sleep) directly examined fireline effects. A single study (9.1%) considered gender and age jointly (Theleritis et al. 2020), and a single study considered age and ethnicity jointly (Leykin et al. 2013). One study considered gender alone (Vincent et al. 2015).

Psychological studies primarily centered on maintaining cognitive performance and either mitigating, managing, or assessing environmental factors that may precipitate declines via stress (Palmer 2014), sleep deprivation (e.g., Bougard et al. 2016), lack of training and support (Cherry et al. 2021), or poor diet (Bode et al. 2022). Absent from many studies were considerations of mental health history which may impact wildland firefighters’ experiences in the field (Ragland et al. 2023). Mental health and social support are emerging fields of interest in wildland firefighter environmental health research, and one survey found that 16% of respondents have had suicidal thoughts that were worsened by the stress of their jobs (Verble et al. 2022).

Performance studies

Performance studies combine medical and occupational elements to assess human biometrics that can be related to job-specific tasks. A total of 16 wildland firefighter environmental health performance studies were identified, conducted between 1999 and 2022. The most common topics addressed were performance on work tests (N = 4) and rate of travel (N = 2). Most studies were conducted in North America (N = 4) and two were conducted in Europe (N = 2, Spain). Common biometrics utilized were walking and running speed, skin and core temperature, and body mass. Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 320 participants with a median of 52.5 (quartile 17–80.5). Fifteen studies lasted for one fire season (approximately 6 months) or less. One study ran for 4 years (Gaskill et al. 2020). Of all categories, performance studies were the most likely to consider demographic factors. Fifteen studies (93.8%) considered some combination of age and gender, together or independently (4 both, 11 gender, 5 age); however, none considered ethnicity. Six studies performed direct fireline measures of performance (37.5%).

Occupational and safety studies

We identified 56 studies that covered topics relating to occupational health and safety of wildland firefighters. Studies were published between 1992 and 2022 in North America (N = 47), Europe (N = 5), Australia and Asia (N = 3), and Latin America (N = 1). One study (Carballo-Leyenda et al. 2022) occurred in both Europe and Latin America and is included in the count for both regions. Themes included job-based environmental exposure (smoke: N = 13, 23.2%; heat: N = 3, 5.4%; other: N = 1, 1.8%), personal protective equipment (N = 7, 12.5%), leadership and decision making (N = 6, 10.7%), fatalities and injuries (N = 6, 10.7%), evacuation and safety zones (N = 5, 8.9%), communication (N = 4, 7.1%), training (N = 4, 7.1%), gender (N = 3, 5.4%), and impacts of the job on task performance (N = 2, 3.6%). A total of 38 (67.8%) studies included human participants, and the mean number of participants per study was 31 (quartile 15–245).

Study length varied widely by methodology. The longest study retrospectively analyzed 70 years of fatality data (Cardil et al. 2017) and the shortest observed wildland firefighters on an active wildfire for 4 six-hour shifts (Phillips et al. 2015). Most studies observed direct effects of fire (N = 38, 67.8%). Few studies accounted for age (N = 10, 17.9%), gender (N = 12, 21.4%) or ethnicity (N = 1, 1.8%) in their analyses. While many studies included human subjects, less than half included survey responses of participant experiences (N = 21, 37.5%). All studies focused on operational wildland firefighters’ working environments.

Occupational studies often cited a lack of sufficient training for and use of safety equipment (e.g., hearing protection, Broyles et al. 2019), high rates of job-related environmental exposure to pollutants (e.g., Adetona et al. 2017a, b), gender disparity (Reimer 2017), and a need for improved psycho-social support systems (e.g., Leduc 2020) as key priorities for improvements to the field. While safety is often considered in the context of operations and protective gear (e.g., McQuerry & Easter 2022), less work has been done to assess cultural and social aspects of safety and well-being in occupational settings, and this is also an important line of future research.

Critical gaps in knowledge

Our review identifies three emergent themes—(1) a lack of geographic and demographic diversity, (2) limited knowledge of the interaction between physiological factors and the natural environment, and (3) a broad need for prioritization of wildland firefighter health, safety, and well-being in future research. Addressing these themes will represent improvements toward enhancing the comprehensivity, inclusivity, applicability, and relevance of future research and help advance the state of the field.

Multiscale geographic diversity is essential to fully encompass the heterogeneity of landscapes, ecosystems, and wildland firefighters that exist. To date, wildland firefighter environmental health has been unstudied in significant portions of the globe where fires are most widespread and deadly (Figs. 2 and 3). Fireline hazards, smoke composition, interpersonal interactions, and medical risk factors will vary among localities and populations: Neglecting to consider these differences leaves a substantial portion of the world’s wildland firefighters without access to quality environmental health data and unable to make informed decisions to protect themselves from unnecessary exposures. For example, Wu et al. found that wildland firefighters in the midwestern USA who worked on prescribed burns have a higher incidence of urinary mutagenicity and systemic oxidative changes associated with smoke exposure than wildland firefighters in other areas of the country (2020), highlighting the importance of geographic diversity of studies.

Further, wildland firefighting strategies and wildland firefighter demographics vary significantly across geographic regions. Our review highlights the need for demographic diversity in studies of wildland firefighter environmental health. Environmental justice research has repeatedly demonstrated that the effects of environmental inequities are disproportionately born by minority groups (e.g., Bullard & Wright 1993; McGregor et al. 2020), and non-white wildland firefighters were more likely to experience injury or illness on the fireline than white wildland firefighters (Verble et al. 2022). Further, variables such as sexual orientation, veteran status, and mental health status may be important to the work experiences of wildland firefighters (Ragland et al. 2023). By neglecting to intersectionally consider important demographic and socioeconomic data about wildland firefighters, important patterns and contributing factors to environmental health risk are likely being obscured.

The current state of wildland firefighter environmental health literature almost exclusively considers operational wildland firefighters (except Palmer 2014). While operational wildland firefighters are the most conspicuous members of the enterprise, wildland firefighting consists of an interconnected web of actors, each contributing to the success of suppression efforts through their roles. Wildland firefighters include people working in wildland fire dispatch, logistics, radio operations, incident command, aviation, supply cache management, and fuels management, among others. Some of these firefighters may not experience heat or smoke exposure, but they experience many other high-stress and demanding elements of the wildland fire environment, including trauma, sleep deprivation, driving and transportation hazards, interpersonal interactions, and others. Further studies are needed to understand the impacts of the work environment on their health and well-being.

Finally, the field has a deficient understanding of the relationship between physiological and physical parameters of work and exposure. As wildland firefighters work harder in smokier conditions, their ventilation rate increases, which likely increases the amount of exposure to airborne particulate matter and smoke. Likewise, not all positions on a fireline experience the same amount of smoke, and this is largely governed by terrain and atmospheric conditions. Reinhardt and Ottar linked smoke exposure to fireline position, fire type (prescribed fires yielded more exposure), task, and weather (2004); however, they stopped short of incorporating physiological measurements such as heart rate and ventilation rate into their study. We could identify no studies that included the combination of physiology, local geography, and exposure; however, synthesizing these variables will further resolve our understanding of fireline risk and inform future fire management and decision making. Additionally, our study found that researchers often pursued topics long enough to publish 1–3 papers, suggesting that funding may be a significant limiter in their ability to sustain research in this arena. Thus, researcher attrition may be driving a lack of deep exploration in the field, leaving critical gaps in knowledge and unaddressed needs for this population. Increasing focused and dedicated research efforts requires the commitment of both researchers and government agencies.

Limitations

Considerable variation in sampling methods, populations, and definitions of disease and fitness exists among studies. Subjective questionnaires also present inherent and systemic bias, which make assessment of differences among results difficult. Further, restricting this review to peer-reviewed literature excluded numerous federal technical reports that contain valuable and relevant topical data. Despite these limitations, this review allows an opportunity to summarize and discuss the overarching themes within each subtopic, and this contribution advances our current understanding of the environmental health of wildland firefighters and offers paths for future research.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the scope of the current wildland firefighter environmental health literature reveals a need for more research into the psychological, physical, occupational, and overall health, well-being, and safety of a workforce tasked with defending communities, protecting natural resources, and preventing future wildfires. Studies that consider multifactor and interactive factors and that integrate physiogeography, ecology, sociology, and physiology will produce the most robust and informative science. Future work should prioritize these interdisciplinary perspectives, as they represent the frontiers of the field.

Availability of data and materials

All articles used in this publication are available online through their respective publishers and also at www.wildlandfiresurvey.com.

Abbreviations

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

References

Abreu, A., C. Costa, S. Pinho E Silva, S. Morais, M. do Carmo Pereira, A. Fernandes, V. Moraes de Andrade, J.P. Teixeira, and S. Costa. 2017. Wood smoke exposure of Portuguese wildland firefighters: DNA and oxidative damage evaluation. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 80: 596–604.

Adetona, A.M. 2016. Wildland Firefighter work task-related smoke exposures at prescribed burns and their effect on pro inflammatory biomarkers and urinary mutagenecity. Dissertation. University of Georgia.

Adetona, O., D.B. Hall, and L.P. Naeher. 2011. Lung function changes in wildland firefighters working at prescribed burns. Inhalation Toxicology 23: 835–841.

Adetona, O., Zhang, J., Hall, D., Wang, J.S., Vena, J., Naeher, L.P. 2012. The effect of occupational woodsmoke exposure on oxidative stress among wildland firefighters. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 185: A4701.

Adetona, O., C.D. Simpson, G. Onstad, and L.P. Naeher. 2013a. Exposure of wildland firefighters to carbon monoxide, fine particles, and levoglucosan. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 57: 979–991.

Adetona, O., J. Zhang, D.B. Hall, J.-S. Wang, J.E. Vena, and L.P. Naeher. 2013b. Occupational exposure to woodsmoke and oxidative stress in wildland firefighters. Science of the Total Environment 449: 269–275.

Adetona, O., C.D. Simpson, A. Sjodin, A.M. Calafat, and L.P. Naeher. 2017a. Hydroxylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as biomarkers of exposure to wood smoke in wildland firefighters. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology 27: 78–83.

Adetona, A.M., O. Adetona, R.M. Gogal Jr., D. Diaz-Sanchez, S.L. Rathbun, and L.P. Naeher. 2017b. Impact of work task-related acute occupational smoke exposures on select proinflammatory immune parameters in wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 59: 679–690.

Alfano, C.A., J.L. Bower, C. Connaboy, N.H. Agha, F.L. Baker, K.A. Smith, C.J. So, and R.J. Simpson. 2021. Mental health, physical symptoms, and biomarkers of stress during prolonged exposure to Antarctica’s extreme environment. Acta Astronautica 181: 405–413.

Amster, E., S.S. Fertig, U. Baharal, S. Linn, M.S. Green, Z. Lencovsky, and R.S. Carel. 2013. Occupational exposures among firefighters and police during the Carmel forest fire: The Carmel Cohort Study. Israeli Medical Association Journal 15: 288–292.

Bayham, J., E. Belval, M.P. Thompson, C. Dunn, C.S. Stonesifer, and D.E. Calkin. 2020. Weather, risk, and resource orders on large wildland fires in the western United States. Forests 11: 169.

Bellingar, T.A. 1994. The development of prototype wildland firefighter protective clothing. Thesis. Auburn University.

Belval, E.J., D.E. Calkin, Y. Wei, C.S. Stonesifer, M.P. Thompson, and A. Masarie. 2018. Examining dispatching practices for Interagency Hotshot Crews to reduce seasonal travel distance and manage fatigue. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27: 569–580.

Betchley, C., J. Koenig, G. van Belle, H. Checkoway, and T. Reinhardt. 1997. Pulmonary function and respiratory symptoms in forest firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 31: 503–509.

Bode, K., L. Smith, T. Wells, G. Wollengerg, and J. Joyce. 2022. The relationship between diet and suicide risk and resilience in wildland firefighters. Current Developments in Nutrition 6: 348.

Bougard, C., Moussay, S., Espie, S., Davenne, D. 2016. The effects of sleep deprivation and time of day on cognitive performance. Biological Rhythm Research 47: 401-415.

Britton, C., C.F. Lynch, M. Ramirez, J. Torner, C. Buresh, and C. Peek-Asa. 2013a. Epidemiology of injuries to wildland firefighters. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31: 339–345.

Britton, C., M. Ramirez, C.F. Lynch, J. Torner, and C. Peek-Asa. 2013b. Risk of injury by job assignment among federal wildland firefighters, United States, 2003–2007. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 19: 77–84.

Brown, P. 2013. Integrating medical and environmental sociology with environmental health: Crossing boundaries and building connections through advocacy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 54: 145–164.

Broyles, G., C.R. Butler, and C.A. Kardous. 2017. Noise exposure among federal wildland fire fighters. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 141: 177–183.

Broyles, G., C.A. Kardous, P.B. Shaw, and E.F. Krieg. 2019. Noise exposures and perceptions of hearing conservation programs among wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 16: 775–784.

Bullard, R.D., and B.H. Wright. 1993. Environmental justice for all: Community perspectives on health and research. Toxicology and Industrial Health 9: 821–841.

Burbank, M.D. 2016. Crisis decision making: An examination of executive leadership in a state forestry service. Thesis: Texas A&M University.

Butler, B.W., and J.D. Cohen. 1998. Firefighter safety zones: A theoretical model based on radiative heating. International Journal of Wildland Fire 8: 73–77.

Butler, C., Marsh, S., Domitrovich, Helmkamp, J. 2017. Wildland firefighter deaths in the United States: a comparison of existing surveillance systems. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 14: 258-270.

Campbell, M.J., P.E. Dennison, and B.W. Butler. 2017a. A LiDAR-based analysis of the effects of slope, vegetation density, and ground surface roughness on travel rates for wildland firefighter escape route mapping. International Journal of Wildland Fire 26: 884–895.

Campbell, M.J., P.E. Dennison, and B.W. Butler. 2017b. Safe separation distance score: A new metric for evaluating wildland firefighter safety zones using lidar. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 31: 1448–1466.

Carballo-Leyenda, B., J.G. Villa, J. López-Satué, and J.A. Rodríguez-Marroyo. 2017. Impact of different personal protective clothing on wildland firefighters’ physiological strain. Frontiers in Physiology 8: 44934.

Carballo-Leyenda, B., J.G. Villa, J. López-Satué, P. Sanchez-Collado, and J.A. Rodríguez-Marroyo. 2018. Fractional contribution of wildland firefighters’ personal protective equipment on physiological strain. Frontiers in Physiology 9: 10.

Carballo-Leyenda, B., J.G. Villa, J. López-Satué, P. Sanchez-Collado, and J.A. Rodríguez-Marroyo. 2019. Characterizing wildland firefighters’ thermal environment during live-fire suppression. Frontiers in Physiology 10: 8.

Carballo-Leyenda, B., J.G. Villa, J. López-Satué, and J.A. Rodríguez-Marroyo. 2021a. Wildland firefighters’ thermal exposure in relation to suppression tasks. International Journal of Wildland Fire 30: 475–483.

Carballo-Leyenda, B., J. Gutierrez-Arroyo, F. Garcia-Heras, P. Sanchez-Collado, J.G. Villa-Vicente, and J.A. Rodriguez-Marroyo. 2021b. Influence of personal protective equipment on wildland firefighters’ physiological response and performance during the pack test. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 44935.

Carballo-Leyenda, B., J.G. Villa-Vicente, J.A. Rodríguez-Marroyo, G.M. Delogue, and D.M. Molina-Terrén. 2022. Perceptions of heat stress, heat strain and mitigation practices in wildfire suppression across southern Europe and Latin America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 44938.

Cardil, A., G.M. Delogu, and D.M. Molina-Terrén. 2017. Fatalities in wildland fires from 1945 to 2015 in Sardinia (Italy). Cerne 23: 175–184.

Cherry, N., J.-M. Galarneau, W. Haynes, and B. Sluggett. 2021. The role of organizational supports in mitigating mental ill health in firefighters: A cohort study in Alberta, Canada. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 64: 593–601.

Cherry, N., N. Bronznitsky, M. Fedun, and T. Zadunayski. 2022. Respiratory tract and eye symptoms in wildland firefighters in two Canadian provinces: Impact of discretionary use of an N95 mask during successive rotations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 136–158.

Christison, K.S., S. Gurney, and C.L. Dumke. 2021a. Effect of vented helmets on heat stress during wildland firefighter simulation. International Journal of Wildland Fire 30: 645–651.

Christison, K.S., S. Gurney, J.A. Sol, C.M. Williamson-Reisdorph, T.S. Quindry, J.C. Quindry, and C.L. Dumke. 2021b. Muscle damage and overreaching during wildland firefighter critical training. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63: 350–356.

Christison, K.S. 2020. Muscle soreness and damage during wildland firefighter critical training. Thesis. University of Montana.

Clarke, C.K., and M.J. Zak. 1999. Fatalities to law enforcement officers and firefighters, 1997–97. In Compensation and Working Conditions Summer 1999, 3–7. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Collins, C.N. 2018. Understanding factors contributing to wildland firefighter health, safety, and performance: a pilot study on smokejumpers. Thesis. University of Idaho.

Cuddy, J.S., and B.C. Ruby. 2011. High work output combined with high ambient temperatures caused heat exhaustion in a wildland firefighter despite high fluid intake. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 22: 122–125.

Cuddy, J.S., J.A. Sol, W.S. Hailes, and B.C. Ruby. 2015. Work patterns dictate energy demands and thermal strain during wildland firefighting. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 26: 221–226.

Cvirn, M.A., J. Dorrian, B.P. Smith, S.M. Jay, G.E. Vincent, and S.A. Ferguson. 2017. The sleep architecture of Australian volunteer firefighters during a multi-day simulated wildfire suppression: Impact of sleep restriction and temperature. Accident Analysis and Prevention 99: 389–394.

DenHartog, E.A., M.A. Walker, and R.L. Barker. 2015. Total heat loss as a predictor of physiological response in wildland firefighter gear. Textile Research Journal 86: 710–726.

Domitrovich, J.W. 2011. Aerobic fitness characteristics of United States wildland fire smokejumpers. Thesis, 7–26. University of Montana.

Domitrovich, J.W. 2011a. Wildland fire uniform configurations on physiological measures of exercise-heat stress. Thesis, 56–78. University of Montana.

Domitrovich, J.W. 2011b. Validation of the smokejumper physical fitness test. Thesis, 26–55. University of Montana.

Dorman, S.C., and S.A. Ritz. 2014. Smoke exposure has transient pulmonary and systemic effects in wildland firefighters. Journal Respiratory Medicine 2014: 943219.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2006. Structure fire response times. In U.S. Fire Administration National Fire Data Center, vol. 5, 1–5.

Ferguson, M.D., E.O. Semmens, C. Dumke, J.C. Quindry, and T.J. Ward. 2016. Measured pulmonary and systemic markers of inflammation and oxidative stress following wildland firefighter simulations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58: 407–413.

Ferguson, M.D., E.O. Semmens, E. Weiler, J. Domitrovich, M. French, C. Migliaccio, C. Palmer, C. Dumke, and T. Ward. 2017. Lung function measures following simulated wildland firefighter exposures. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 14: 738–747.

Fox, R., E. Gabor, D. Thomas, J. Ziegler, and A. Black. 2017. Cultivating a reluctance to simplify: Exploring the radio communication context in wildland firefighting. International Journal of Wildland Fire 26: 719–731.

Fryer, G.K. 2012. Wildland firefighter entrapment avoidance: Developing evacuation trigger points utilizing the Wildland Urban Interface Evacuation (WUIVAC) fire spread model. Thesis. University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Fryer, G.K., P.E. Dennison, and T.J. Cova. 2013. Wildland firefighter entrapment avoidance: Modelling evacuation triggers. International Journal of Wildland Fire 22: 883–893.

Gabor, E. 2015. Words matter: Radio misunderstandings in wildland firefighting. International Journal of Wildland Fire 24: 580–588.

Garcia-Heras, F., J. Gutierrez-Arroyo, P. Leon-Guereno, B. Carballo-Leyenda, and J.A. Rodriguez-Marroyo. 2022. Chronic pain in Spanish wildland firefighters. Journal of Clinical Medicine 11: 44936.

Gaskill, S.E., C.L. Dumke, C.G. Palmer, B.C. Ruby, J.W. Domitrovich, and J.A. Sol. 2020. Seasonal changes in wildland firefighter fitness and body composition. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 29: 294–303.

Gaughan, D.M., J.M. Cox-Ganser, P.L. Enright, R.M. Castellan, G.R. Wagner, G.R. Hobbs, T.A. Bledsoe, P.D. Siegel, K. Kreiss, and D.N. Weissman. 2008. Acute upper and lower respiratory effects in wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 50: 1019–1028.

Gaughan, D.M., P.D. Siegel, M.D. Hughes, C. Chang, B.F. Law, C.R. Campbell, J.C. Richards, S.F. Kales, M. Chertok, L. Kobzik, P. Nguyen, C.R. O’Donnell, M. Kiefer, G.R. Wagner, and D.C. Christiani. 2014a. Arterial stiffness, oxidative stress, and smoke exposure in wildland firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 57: 748–756.

Gaughan, D.M., C.A. Piacitelli, B.T. Chen, B.F. Law, M.A. Virji, N.T. Edwards, P.L. Enright, D.E. Schwegler-Berry, S.S. Leonard, G.R. Wagner, L. Kobzik, S.N. Kales, M.D. Hughes, D.C. Christiani, P.D. Seigel, J.M. Cox-Ganser, and M.D. Hoover. 2014b. Exposures and cross-shift lung function declines in wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Hygiene 11: 591–603.

Gordon, H., and M. Lariviere. 2014. Physical and psychological determinants of injury in Ontario forest firefighters. Occupational Medicine 64: 583–588.

Gumieniak, R.J., N. Gledhill, and V.K. Jamnik. 2018. Physical employment standard for Canadian wildland firefighters: Examining test-retest reliability and the impact of familiarisation and physical fitness training. Ergonomics 61: 1324–1333.

Gurney, S.C., K.S. Christison, T. Stenersen, and C.L. Dumke. 2021a. Effect of uncompensable heat from the wildland firefighter helmet. International Journal of Wildland Fire 30: 990–997.

Gurney, S.C., K.S. Christison, J.A. Sol, T.S. Quindry, J.C. Quindry, and C.L. Dumke. 2021b. Alterations in metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors during critical training in wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63: 594–599.

Huber, M., J.A. Knottnerus, L. Green, H. van der Horst, A.R. Jadad, D. Kromhout, B. Leonard, K. Lorig, M.I. Loureiro, J.W.M. van der Meer, P. Schnabel, R. Smith, C. van Weel, and H. Smid. 2011. How should we define health? British Medical Journal 343: d4163.

Huby, M., and R. Adams. 2009. Interdisciplinarity and participatory approaches to environmental health: Reflections from a workshop on social, economic and behavioural factors in the genesis and health impact of environmental hazards. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 31: 219–226.

Hummel, A., K. Watson, and R. Barker. 2020. Comparison of two test methods for evaluating the radiant protective performance of wildland firefighter protective clothing materials. ASTM International STP 1593: 178–194.

Hunter, A.L., J. Unosson, J.A. Bosson, J.P. Langrish, J. Pourasar, J.B. Raftis, M.R. Miller, A.J. Lucking, C. Boman, R. Nystrom, K. Donaldson, A.D. Flapan, A.S.V. Shah, L. Pung, I. Sadiktsis, S. Masala, R. Westerholm, T. Sandstrom, A. Blomberg, D.E. Newby, and N. Mills. 2014. Effect of wood smoke exposure on vascular function and thrombus formation in healthy fire fighters. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 11: 44939.

Jacquin, L., P. Michelet, F. Brocq, J. Houel, X. Truchet, J. Auffray, J. Carpentier, and Y. Jammes. 2011. Short-term spirometric changes in wildland firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 54: 819–825.

Jeklin, A.T., A.S. Perrotta, H.W. Davies, S.S.D. Bredin, D.A. Paul, and D.E.R. Warburton. 2021. The association between heart rate variability, reaction time, and indicators of workplace fatigue in wildland firefighters. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 94: 823–831.

Laws, R.L., S. Jain, G.S. Cooksey, J. Mohle-Boetani, J. McNary, J. Wilken, R. Harrison, B. Leistikow, D.J. Vugia, G.C. Windham, and B.L. Materna. 2020. Coccidioidomycosis outbreak among inmate wildland firefighters: California, 2017. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 64: 266–273.

Leduc, C. 2020. Development, implementation and evaluation of fitness training and psychosocial education interventions in wildland firefighting. Thesis. Lancaster University, Lancashire.

Leduc, C., S.I. Giga, I.J. Fletcher, M. Young, and S.C. Dorman. 2022. Effectiveness of fitness training and psychosocial education intervention programs in wildland firefighting: A cluster randomized control trial. International Journal of Wildland Fire 31: 799–815.

Lewis, A., and V. Ebbeck. 2014. Mindful and self-compassionate leadership development: Preliminary discussions with wildland fire managers. Journal of Forestry 112: 230–236.

Leykin, D., M. Lahad, and N. Bonneh. 2013. Posttraumatic symptoms and posttraumatic growth of Israeli firefighters, at one month following the Carmel fire disaster. Psychiatry Journal 2013: 44931.

Lui, B., J.S. Cuddy, W.S. Hailes, and B.C. Ruby. 2014. Seasonal heat acclimatization in wildland firefighters. Journal of Thermal Biology 45: 134–140.

Main, L.C., A.P. Wolkow, J.L. Tait, P.D. Gatta, J. Raines, R. Snow, and B. Aisbett. 2020. Firefighter’s acute inflammatory response to wildfire suppression. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62: 145–148.

Materna, B.L., J.R. Jones, P.M. Sutton, N. Rothman, and R.J. Harrison. 1992. Occupational exposures in California wildland fire fighting. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal 53: 69–76.

Materna, B.L., C.P. Koshland, and R.J. Harrison. 1993. Carbon monoxide exposure in wildland firefighting: A comparison of monitoring methods. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 8: 479–487.

McDonald, L.S., and L. Shadow. 2003. Precursor for error: An analysis of wildland fire crew leaders’ attitudes about organizational culture and safety. Third International Wildland Fire Conference 2003: 44938.

McGillis, Z., S.C. Dorman, A. Robertson, M. Lariviere, C. Leduc, T. Eger, B.E. Oddson, and C. Lariviere. 2017. Sleep quantity and quality of Ontario wildland firefighters across a low-hazard fire season. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 59: 1188–1196.

McGregor, D., S. Whitaker, and M. Srithran. 2020. Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 43: 35–40.

McQuerry, M., and E. Easter. 2022. Wildland firefighting personal protective clothing cleaning practices in the United States. Fire Technology 58: 1667–1688.

Metz, A.R., M. Bauer, C. Epperly, G. Stringer, K.E. Marshall, L.M. Webb, M. Hetherington-Rauth, S.R. Matzinger, S.E. Totten, E.A. Travanty, K.M. Good, and A. Burakoff. 2022. Investigation of COVID-19 outbreak among wildland firefighters during wildfire response, Colorado, USA 2020. Emerging Infections Diseases 28: 1551–1558.

Miranda, A.I., V. Martins, P. Cascao, J.H. Amorim, J. Valente, R. Tavares, C. Borrego, O. Tchepel, A.J. Ferreira, C.R. Cordeiro, D.X. Viegas, L.M. Ribeiro, and L.P. Pita. 2010. Monitoring of firefighters exposure to smoke during fire experiments in Portugal. Environment International 36: 736–745.

Miranda, A.I., V. Martins, P. Cascão, J.H. Amorim, J. Valente, C. Borrego, A.J. Ferreira, C.R. Cordeiro, D.X. Viegas, and R. Ottmar. 2012. Wildland smoke exposure values and exhaled breath indicators in firefighters. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 75: 831–843.

Moody, V.J., T.J. Purchio, and C.G. Palmer. 2019. Descriptive analysis of injuries and illnesses self-reported by wildland firefighters. International Journal of Wildland Fire 28: 412–419.

Munn, Z., M.D.J. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 143.

Nagavalli, A., A. Hyummel, H.I. Akyildiz, J. Morton-Aslanis, and R. Baker. 2020. Advanced layering system and design for the increased thermal protection of wildland fire shelters. ASTM International STP 1593: 102–116.

Navarro, K.M., R. Cisneros, E.M. Noth, J.R. Balmes, and S.K. Hammon. 2017. Occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon of wildland firefighters at prescribed and wildland fires. Environmental Science & Technology 51: 6461–6469.

Navarro, K.M., M.T. Kleinman, T.E. Reinhardt, J.R. Balmes, G.A. Broyles, R.D. Ottmar, L.P. Naher, and J.W. Domitrovich. 2019. Wildland firefighter smoke exposure and risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality. Environmental Research 173: 462–468.

Navarro, K.M., C.R. Butler, K. Fent, C.K. Toennis, D. Sammons, A. Ramirez-Cardenas, K.A. Clark, D.L. Smith, M.C. Alexander-Scott, L.E. Pinkerton, J. Eisenberg, and J.W. Domitrovich. 2021a. The wildland firefighter exposure and health effect (WFFEHE) study: Rationale, design, and methods of a repeated-measures study. Annals of Work Exposures and Health 66: 714–727.

Navarro, K.M., M.R. West, K. O’Dell, P. Sen, I.-C. Chen, E.V. Fischer, R.S. Hornbrook, E.C. Apel, A.J. Hills, A. Jarnot, P. DeMott, and J.W. Domitrovich. 2021b. Exposure to particulate matter and estimation of volatile organic compounds across wildland firefighter job tasks. Environmental Science & Technology 55: 11795–11804.

Nelson, J., M.-C.G. Chalbot, Z. Pavicevic, and I.G. Kavouras. 2020. Characterization of exhaled breath condensate (EBC) non-exchangeable hydrogen functional types and lung function of wildland firefighters. Journal of Breath Research 14: 046010.

Nelson, J., M.C.G. Chalbot, I. Tsiodra, N. Mihalopoulos, and I.G. Kavouras. 2021. Physiochemical characterization of personal exposures to smoke aerosol and PAHs of wildland firefighters in prescribed fires. Exposure and Health 13: 105–118.

Niyatiwatchanchai, N., C. Pothirat, W. Chaiwong, C. Liwsrisakun, N. Phetsuk, P. Duangjit, and W. Choomuang. 2022. Short-term effects of air pollutant exposure on small airway dysfunction, spirometry, health-related quality of life, and inflammatory biomarkers in wildland firefighters: A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 19: 1–14.

Oliveira, M., K. Slezakova, M. Jose Alves, A. Fernandes, J.P. Teixeira, C. Delerue-Matos, M. Carmo Pereira, and S. Morais. 2016. Firefighters’ exposure biomonitoring: Impact of firefighting activities on levels of urinary monohydroxyl metabolites. International Journal of Hygeine and Environmental Health 219: 857–866.

Oliveira, M., S. Costa, J. Vaz, A. Fernandes, K. Slezakova, C. Delerue-Matos, J. Teixeira, M. Carmo Pereira, and S. Morais. 2020. Firefighters exposure to fire emissions: Impact on levels of biomarkers of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and genotoxic/oxidative-effects. Journal of Hazardous Materials 383: 121179.

Page, W.G., and B.W. Butler. 2018. Fuel and topographic influences on wildland firefighter burnover fatalities in Southern California. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27: 141–154.

Page, W.G., P.H. Freeborn, B.W. Butler, and W.M. Jolly. 2019. A classification of U.S. wildland firefighter entrapments based on coincident fuels, weather and topography. Fire 2: 1–23.

Palmer, C.G. 2014. Stress and coping in wildland firefighting dispatchers. Journal of Emergency Management 12: 303–314.

Palmer, C.G., S. Gaskill, J. Domitrovich, McNamara, B. Knutson, and A. Spear. 2011. Wildland firefighters and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In Proceedings of the Second Conference on the Human Dimensions of Wildland Fire. GTR-NRS-P-84, ed. S.M. McCaffrey and C.L. Fisher, 9–13. Newtown Square: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Northern Research Station.

Pelletier, C., C. Ross, K. Bailey, T.M. Fyfe, K. Cornish, and E. Koopmans. 2022. Health research priorities for wildland firefighters: A modified Delphi study with stakeholder interviews. British Medical Journal 12: e051227.

Peña Cueto, J.M. 2018. Evaluation of a web-based performance program for wildland firefighters. Thesis. University of Montana, Missoula, Montana.

Peters, M.D.J., C.M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C.B. Soares. 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 141–146.

Peters, B., C. Ballmann, T. Quindry, E.G. Zehner, J. McCroskey, M. Ferguson, T. Ward, C. Dumke, and J.C. Quindry. 2018. Experimental woodsmoke exposure during exercise and blood oxidative stress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60: 1073–1081.

Phillips, M., W. Payne, C. Lord, K. Netto, D. Nichols, and B. Aisbett. 2012. Identification of physically demanding tasks performed during bushfire suppression by Australian rural firefighters. Applied Ergonomics 43: 435–441.

Phillips, M., K. Netto, W. Payne, D. Nichols, C. Lord, N. Brooksbank, and B. Aisbett. 2015. Frequency, intensity, time and type of tasks performed during wildfire suppression. Occupational Medicine and Health Affairs 3: 199.

Phillips, D.B., C.M. Ehnes, B.G. Welch, L.N. Lee, I. Simin, and S.R. Petersen. 2018. Influence of work clothing on physiological responses and performance during treadmill exercise and the wildland firefighter pack test. Applied Ergonomics 68: 313–318.

PMS 841. 2017. NWCG report on wildland firefighter fatalities in the United States: 2017–2016. National Wildfire Coordinating Group.

Podur, J., and M. Wotton. 2010. Will climate change overwhelm fire management capacity? Ecological Modeling 221: 1301–1309.

Pryor, R.R., and J.F. Suyama. 2015. The effects of ice slurry ingestion before exertion in wildland firefighting gear. Prehospital Emergency Care 19: 241–246.

Ragland, M., J. Harrell, M. Ripper, S. Pearson, R. Granberg, and R. Verble. 2023. Gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors influence how wildland firefighters communicate their work experiences. Frontiers in Communication 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1021914.

Ramos, C., and B. Minghelli. 2022. Prevalence and factors associated with poor respiratory function among firefighters exposed to wildfire smoke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 8492–8502.

Reimer, R.D., and C. Eriksen. 2018. The wildfire within: Gender, leadership and wildland fire culture. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27: 715–726.

Reimer, R.D. 2017. The wildfire within: firefighter perspectives on gender and leadership in wildland fire. Thesis. Royal Roads University, Colloid, British Columbia.

Reinhardt, T. 2019. Factors affecting smoke and crystalline silica exposure among wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 16: 175–184.

Reinhardt, T.E., and R.D. Ottmar. 2004. Baseline measurements of smoke exposure among wildland firefighters. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 1: 593–606.

Riley, K.L., C.D. O’Connor, C.J. Dunn, J.R. Haas, R.D. Stratton, and B. Gannon. 2022. A national map of snag hazard to reduce risk to wildland fire responders. Forests 13: 1160–1175.

Roberts, M.S. 2002. A case study of three women firefighters in their assimilation into a medium-sized fire department in southern California. Thesis. California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo.

Robertson, A.H., C. Lariviere, C.R. Leduc, Z. McGillis, A. Godwin, M. Lariviere, and S.C. Dorman. 2017. Novel tools in determining the physiological demands and nutritional practices of Ontario fire rangers during fire deployments. PLoS ONE 12: 44944.

Robinson, M.S., T.R. Anthony, S.R. Littau, P. Herckes, X. Nelson, G.S. Poplin, and J.L. Burgess. 2008. Occupational PAH Exposures during prescribed pile burns. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 52: 497–508.

Rodríguez-Marroyo, J.A., B. Carballo-Leyenda, P. Sánchez-Collado, D. Suárez-Iglesias, and J.G. Villa. 2022. Effect of exercise intensity and thermal strain on wildland firefighters’ central nervous system fatigue. In 13th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, 58–63.

Roise, J., J. Williams, R. Barker, and J. Morton-Aslanis. 2022. Field and full-scale laboratory testing of prototype wildland fire shelters. International Journal of Wildland Fire 31: 518–528.

Rose, R. 2019. Evaluation of wildland firefighter leadership. Thesis. Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Washington.

Ruby, B.C. 1999. Energy expenditure and energy intake during wildfire suppression in male and female firefighters. In Wildland Firefighter Health and Safety: Recommendations of the April 1999 Conference 9E92P47, 26–31.

Ruby, B.C., T.C. Shriver, W. Zderic, B. Sharkey, C. Burks, and S. Tysk. 2002. Total energy expenditure during arduous wildfire suppression. Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise 34: 1048–1054.

Ruby, B.C., G.W. Leadbetter III., D.W. Armstrong, and S.E. Gaskill. 2003a. Wildland firefighter load carriage: Effects on transit time and physiological responses during simulated escape to safety zone. International Journal of Wildland Fire 12: 111–116.

Ruby, B.C., D. Schoeller, B. Sharkey, C. Burks, and S. Tysk. 2003b. Water turnover and changes in body composition during arduous wildfire suppression. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 35: 1760–1765.

Ruby, B.C., R.H. Coker, J. Sol, J. Quindry, and S.J. Montain. 2023. Physiology of the wildland firefighter: Managing extreme energy demands in hostile, smoky, and mountainous environemnts. Comparative Physiology 30: 4587–4615.

Saint Martin, D.R.F., L. Segedi, E.D.M. von Koenig Soares, M.N. Rosenkranz, E.F. Keila, M. Korre, G.E. Molina, D.L. Smith, S.N. Kales, and L.G. Grossi Porto. 2018. Accelerometer-based physical activity and sedentary time assessment in Brazilian wildland firefighters – Brasilia Firefighters Study: 2052. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 50: 499.

Semmens, E.O., J. Domitrovich, K. Conway, and C. Noonan. 2016. A cross-sectional survey of occupational history as a wildland firefighter and health. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 59: 330–335.

Semmens, E.O., C. Leary, M. West, C. Noonan, K. Navarro, and J. Domitrovich. 2021. Carbon monoxide exposures in wildland firefighters in the United States and targets for exposure reduction. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 31: 923–929.

Sharkey, B. 1999. Demands of the job. Wildland Firefighter Health and Safety: Recommendations of the April 1999 Conference 9E92P47, 20–25.

Slaughter, J.C., J. Koenig, and T. Reinhardt. 2004. Association between lung function and exposure to smoke among firefighters at prescribed burns. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 1: 45–49.

Smith, W.R., G. Montopoli, A. Byerly, M. Montopoli, H. Harlow, and A.R. Wheeler. 2013. Mercury toxicity in wildland firefighters. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 24: 141–145.

Sol, J.A., B. Ruby, S. Gaskill, C. Dumke, and J. Domotrovich. 2018. Metabolic demand of hiking in wildland firefighting. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 20: 304–314.

Sol, J.A., M.R. West, J.W. Domitrovich, and B.C. Ruby. 2021. Evaluation of environmental conditions on self-selected work and heat stress in wildland firefighting. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 32: 149–159.

Strang, J.T., C.J. Alfiero, C. Dumke, B. Ruby, and M. Bundle. 2018. Metabolic energy requirements during load carriage: implications for the wildland firefighter arduous pack test. Thesis. University of Montana, Missoula.

Sullivan, P.R. 2020. Modeling wildland firefighter travel rates across varying slopes. Thesis. University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Sullivan, P.R., M. Campbell, P. Dennison, S. Brewer, and B. Butler. 2020. Modeling wildland firefighter travel rates by terrain slope: Results from GPS-tracking of type 1 crew movement. Fire 3: 52.

Sun, G., H.S. Yoo, X.S. Zhang, and N. Pan. 2000. Radiant protective and transport properties of fabrics used by wildland firefighters. Textile Research Journal 70: 567–573.

Swiston, J.R., W. Davidson, S. Attridge, G. Li, M. Brauer, and S. van Eeden. 2008. Wood smoke exposure induces a pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response in firefighters. European Respiratory Journal 31: 129–138.

Taylor, J.G., S. Gillette, R. Hodgson, J. Downing, M. Burns, D. Chavez, and J. Hogan. 2007. Informing the network: Improving communication with interface communities during wildland fire. Human Ecology Review 14: 198–211.

Theleritis, C., C. Psarros, L. Mantonakis, D. Roukas, A. Papaioannou, T. Paparrigopoulos, and J. Bergiannaki. 2020. Coping and its relation to PTSD in Greek firefighters. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 252–259.

Thompson, M.P., D.G. MacGregor, C.J. Dunn, D.E. Calkin, and J. Phipps. 2018. Rethinking the wildland fire management system. Journal of Forestry 116: 382–390.

VanDevanter, N.L., P. Abramson, D. Howard, J. Moon, and P.A. Honore. 2010. Emergency response and public health in Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 16: e16–e25.

Verble, R., S. Pearson, and R. Granberg. 2022. Wildland Fire Survey www.wildlandfiresurvey.com.

Vincent, G., S. Ferguson, J. Tran, B. Larsen, A. Wolkow, and B. Aisbett. 2015. Sleep restriction during simulated wildfire suppression: Effect on physical task performance. PLoS ONE 10: 44942.

Vincent, G., B. Aisbett, B. Larsen, N. Ridgers, R. Snow, and S. Ferguson. 2017. The impact of heat exposure and sleep restriction on firefighters’ performance and physiology during simulated wildfire suppression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 180–195.

Waldron, A.L., and V. Ebbeck. 2015. Developing wildland firefighters’ performance capacity through awareness-based processes: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments 12: 3.

Waldron, A.L., D. Schary, and B.J. Cardinal. 2015. Measuring wildland fire leadership: The crewmember perceived leadership scale. International Journal of Wildfire 24: 1168–1175.

Watkins, E.R., A. Walker, E. Mol, S. Jahnke, and A.J. Richardson. 2012. Women firefighters’ health and well-being: An international survey. Women’s Health Issues 29: 424–431.

Williams-Bell, F.M., B. Aisbett, B. Murphy, and B. Larsen. 2017. The effects of simulated wildland firefighting tasks on core temperature and cognitive function under very hot conditions. Frontiers in Physiology 8: 44936.

Wolfe, C.M., W. Green, A. Cognetta Jr., and H. Hatfield. 2012. Heat-induced squamous cell carcinoma of the lower extremities in a wildland firefighter. Journal of American Dermatology 67: E272–E273.

Wolklow, A., S. Ferguson, G. Vincent, B. Larsen, B. Aisbett, and L.C. Main. 2015. The impact of sleep restriction and simulated physical firefighting work on acute inflammatory stress responses. PLoS ONE 10: e0138128.

Wu, C.-M., A. Adetona, C.C. Song, L. Naeher, and O. Adetona. 2020a. Measuring acute pulmonary responses to occupational wildland fire smoke exposure using exhaled breath condensate. Archives of Environmental and Occupational Health 75: 65–69.

Wu, C.-M., S. Warren, D. DeMarini, C. Song, and O. Adetona. 2020b. Urinary mutagenicity and oxidative status of wildland firefighters working at prescribed burns in a midwestern US forest. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 78: 315–322.

Wu, C.-M., O. Adetona, and C. Song. 2021a. Acute cardiovascular responses of wildland firefighters to working at prescribed burn. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 237: 113827–113833.

Wu, C.-M., C. Song, R. Cartier, J. Kremer, L. Naeher, and O. Adetona. 2021b. Characterization of occupational smoke exposure among wildland firefighters in the midwestern United States. Environmental Research 193: 110541–110549.

Yoo, H.S., G. Sun, and N. Pan. 2000. Thermal protective performance and comfort of wildland firefighter clothing: The transport properties of multilayer fabric systems. ASTM International Selected Technical Papers STP 1386: 504–518.

Acknowledgements

A particularly deep thank you to the Missouri S&T Interlibrary Loan staff who worked tirelessly to acquire and amass literature for this project. The Missouri S&T Biological Sciences Write Club encouraged the production of this manuscript.

Funding

Students were supported through a grant from the United States Department of Defense (Grant No. W911NF2220200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RMV compiled literature, wrote the manuscript, and conducted analyses. RMG conceived the project and compiled the original literature. MRR compiled and organized literature, edited the manuscript, conducted analyses, and categorized data. OC, AP, and SWP categorized data and conducted analyses. SW conducted analyses, prepared figures, and categorized data. MBH wrote the manuscript and analyzed and categorized data.

Authors’ information

SWP and RMG are wildland firefighters. MBH and MRR are graduate researchers. OC, SW, and AP are undergraduate researchers.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. No human subjects were used in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Held, M.B., Ragland, M.R., Wood, S. et al. Environmental health of wildland firefighters: a scoping review. fire ecol 20, 16 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00235-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00235-x