Abstract

Background

Despite recent advances in understanding the drivers of tree-level delayed mortality, we lack a method for mapping delayed mortality at landscape and regional scales. Consequently, the extent, magnitude, and effects of delayed mortality on post-fire landscape patterns of burn severity are unknown. We introduce a remote sensing approach for mapping delayed mortality based on post-fire decline in the normalized burn ratio (NBR). NBR decline is defined as the change in NBR between the first post-fire measurement and the minimum NBR value up to 5 years post-fire for each pixel. We validate the method with high-resolution aerial photography from six wildfires in California, Oregon, and Washington, USA, and then compare the extent, magnitude, and effects of delayed mortality on landscape patterns of burn severity among fires and forest types.

Results

NBR decline was significantly correlated with post-fire canopy mortality (r2 = 0.50) and predicted the presence of delayed mortality with 83% accuracy based on a threshold of 105 NBR decline. Plots with NBR decline greater than 105 were 23 times more likely to experience delayed mortality than those below the threshold (p < 0.001). Delayed mortality occurred across 6–38% of fire perimeters not affected by stand-replacing fire, generally affecting more areas in cold (22–41%) and wet (30%) forest types than in dry (1.7–19%) types. The total area initially mapped as unburned/very low-severity declined an average of 38.1% and generally persisted in smaller, more fragmented patches when considering delayed mortality. The total area initially mapped as high-severity increased an average of 16.2% and shifted towards larger, more contiguous patches.

Conclusions

Differences between 1- and 5-year post-fire burn severity maps depict dynamic post-fire mosaics resulting from delayed mortality, with variability among fires reflecting a range of potential drivers. We demonstrate that tree-level delayed mortality scales up to alter higher-level landscape patterns of burn severity with important implications for forest resilience and a range of fire-driven ecological outcomes. Our method can complement existing tree-level studies on drivers of delayed mortality, refine mapping of fire refugia, inform estimates of habitat and carbon losses, and provide a more comprehensive assessment of landscape and regional scale fire effects and trends.

Resumen

Antecedentes

A pesar de los recientes avances en el conocimiento sobre las causas de la mortalidad tardía (post-fuego) a nivel de árboles, carecemos de un método para mapear esta mortalidad tardía a escala regional o de paisaje. Consecuentemente, la extensión, magnitud, y efectos de esta mortalidad tardía en patrones de severidad en paisajes post-fuego, son desconocidos. Introdujimos una aproximación usando sensores remotos para mapear la mortalidad tardía basados en declinaciones post-fuego en la relación normalizada de quema (NBR o Normalized Burn Ratio en Inglés). La declinación del NBR está definida como el cambio en NBR entre la primera medición post-fuego y el valor mínimo del NBR hasta cinco años luego del fuego para cada píxel. Validamos el método con fotografías aéreas de alta resolución en seis incendios en California, EEUU; luego comparamos la extensión, magnitud, y efectos de esa mortalidad tardía en los patrones de severidad de paisajes entre diferentes incendios y tipos forestales.

Resultados

La declinación del NBR se correlacionó significativamente con la mortalidad de doseles (r2 = 0,50), y predijo la presencia de mortalidad tardía con un 83% de exactitud basada en un umbral de 105 de declinación en el NBR. Las parcelas con una declinación NBR mayor a 105 fueron 23 veces más probable que experimenten una mortalidad tardía que aquellas que estaban por debajo de este umbral (p < 0,001). La mortalidad tardía ocurrió a través de 6 a 38% de los perímetros de fuego no afectados por incendios de reemplazo de rodales, afectado generalmente más área en tipos forestales de sitios fríos (22–41%) y húmedos (30%), que en tipos forestales de sitios secos (1,7–19%). El área total inicialmente mapeada como no quemada, o quemada a muy baja severidad, declinó un promedio de 38,1% y persistió generalmente en parches pequeños y fragmentados cuando fue considerada la mortalidad tardía. El área total inicialmente mapeada como de alta severidad se incrementó en promedio un 16,2% y derivó hacia parches más grandes y contiguos.

Conclusiones

Los mapas con las diferencias en severidad entre uno y cinco años post-fuego muestran mosaicos dinámicos que resultan de la mortalidad tardía, con variabilidades entre incendios, que reflejan un rango potencial conducente a esas situaciones. Demostramos que la mortalidad tardía a nivel de árboles, escala hasta alterar niveles más altos de severidad de incendios a escala de paisajes con importantes implicancias para la resiliencia de los bosques y un rango de resultados ecológicos derivados de los incendios. Nuestro método puede complementar los estudios existentes a nivel de árboles sobre los conducentes a la mortalidad tardía, refinar mapas de los refugios de fuego, informar estimaciones de hábitat y pérdidas de carbono, y proveer de una determinación más comprensiva de los efectos del fuego a nivel de paisaje, regional y sus tendencias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Numerous field studies from around the world document the occurrence of delayed tree mortality following fire (Barlow et al. 2003, Schwilk et al. 2006, Catry et al. 2010, Angers et al. 2011, van Mantgem et al. 2011, Cansler et al. 2020, Robbins et al. 2022). Studies tracking individual trees following fire document an important role of fire-related injury (e.g., crown scorch), pre- and post-fire climate, competition from surviving trees, and insect and pathogens in predicting tree survival in the years following fire (Hood and Bentz 2007, van Mantgem et al. 2013; Hood et al. 2018; Barker et al. 2022). Despite these advances in understanding the drivers of delayed mortality at the individual tree level, we lack a generalizable method for characterizing and quantifying delayed tree mortality at landscape and regional scales. The potential extent, magnitude, and effects of delayed mortality on post-fire landscape patterns of burn severity remain largely unknown.

Maps derived from remotely sensed imagery quantify fire effects and provide spatial data on patterns of burn severity and the magnitude and extent of tree mortality going back to the mid-1980s. These maps are an essential data source for ecological studies of landscape, regional, and continental fire effects across North America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia (Miller and Yool 2002, Soverel et al. 2010, Guo et al. 2022, Dwomoh and Wimberly 2017, Collins et al. 2018). The primary method for mapping fire-induced tree mortality and burn severity is based on change in the Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR) from before and after fire occurrence (Key and Benson 1999). NBR compares near-infrared and short-wave infrared reflectance to highlight changes in vegetative cover and exposure of bare mineral soil (Key and Benson 1999). Absolute and relative changes in this index are correlated with both composite burn indices (Cocke et al. 2005; Wimberly and Reilly 2007; Cansler and McKenzie 2012; Parks et al. 2014) and tree mortality observed in post-fire field studies (Miller and Thode 2007; Reilly et al. 2017).

As the primary basis for assessing trends, drivers, and spatial patterns of burn severity, Landsat-based burn severity maps are an essential tool for scientists and forest managers. Burn severity maps often provide the basis for post-fire restoration planning (e.g., Meyer et al. 2021), estimating habitat loss (Lesmeister et al. 2021; Palm et al. 2022) and carbon emissions (Zhao et al. 2021), and mapping biological legacies such as small patches of surviving legacy trees and patches of fire refugia that were unburned or experienced minimal fire effects (Krawchuk et al. 2020). However, these applications are currently based on immediate or 1-year post-fire assessments that inevitably underestimate severity wherever delayed mortality occurs. Incorporating the effects of delayed mortality can provide a more refined characterization and understanding of fire effects at landscape and regional scales.

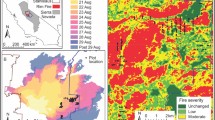

We developed a novel method for mapping delayed mortality using an annual Landsat time-series approach. We first describe the method for mapping delayed mortality up to 5 years post-fire and validate it with high-resolution aerial photo interpretation from six fires in Oregon, Washington, and California (Fig. 1). We then assess the extent and magnitude of delayed mortality and compare among fires and forest types. Finally, we compare the effects of delayed mortality on spatial patterns of classified burn severity across all fires.

Study area in Oregon, California, and Washington with locations of six study fires from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity program (MTBS; Eidenshink et al. 2007)

Methods

Study extent

We selected six study fires across a latitudinal gradient of forested ecoregions in California, Oregon, and Washington (Table 1, Fig. 1). We chose fires based on the availability of high-resolution aerial photography from the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) at 1, 3, and, 5 years post-fire. Fires were a minimum size of 1000 hectares and included high-severity patches according to immediate burn severity data from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity program (MTBS; Eidenshenk et al. 2007). The study fires include a range of forest types (Table 2; Simpson 2021) that span broad biophysical and climatic gradients and differ in terms of post-fire climatic conditions (Fig. S1).

Remote sensing methods

We assembled a stack of annual normalized burn ratio (NBR) grids from a medoid composite of surface reflectance from USGS Collection 2. Cloud, shadow, and snow as identified by the QA bands were masked using Google Earth Engine (Gorelick et al. 2017). NBR is calculated (Eq. 1) using a ratio derived from the near-infrared band (NIR) and the short-wave infrared (SWIR) band as:

Once stacks of annual composites were assembled, we used NBR from 1 year before the fire to represent the pre-fire condition. Non-forest cover from the Landscape Change Monitoring System (LCMS) and salvage logging (digitized manually based on time series imagery from Landsat and NAIP) were masked and excluded from further analysis. We calculated a pixel-scale minimum NBR composite based on the lowest NBR value observed over the 5 years following fire (Fig. 2; Eq. 2). NBR decline was defined as the change in NBR between the first post-fire measurement and the delayed minimum (Eq. 3). We then calculated the relative change in the normalized burn ratio (RdNBR; Miller et al. 2009) for immediate and delayed burn severity using the year preceding the fire and the first-year post-fire and 5-year minimum, respectively (Eq. 4).

where min represents a pixel-wise minimum over a set of years y.

where NBR1 represents the NBR 1 year after fire.

where NBRpre and NBRpost represent the NBR 1 year before and after fire, respectively.

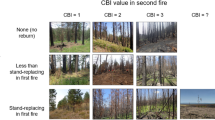

Validation

A total of 353 30-m pixel plots were randomly selected and interpreted across the six study fires. To ensure a relatively even distribution of plots in areas with and without delayed mortality, we stratified based on NBR decline in the following classes: no change (0), low (1–75), moderate (75–150), high (150–225), and very high (> 225) spectral decline. Plots were allocated within these strata to be reasonably representative of continuous NBR decline values across the study area, but class balance was prioritized over a strictly proportional distribution which would have been too heavily weighted towards zero-change pixels.

In each 900-m2 plot, corresponding to a single Landsat pixel, we estimated live tree canopy cover and live tree counts at 1, 3, and 5 years after fire using false color composites from NAIP imagery. We defined the presence of delayed mortality as any decrease in live tree count after the first post-fire year. Of the allocated plots, 34 were removed as they fell within non-forest or salvaged areas that were masked from analysis, and 11 were skipped because the presence or absence of delayed mortality could not be confidently determined, typically due to inconsistent lighting or geometric error between images. We then extracted NBR change at the Landsat pixel overlapping each of the 308 remaining plots.

We trained a logistic regression classifier to predict the presence or absence of delayed mortality based on the magnitude of NBR decline using the scikit-learn package in Python (Pedregosa et al. 2011). We used a Monte Carlo cross-validation approach, training and testing the model with 100 different random 50% splits of the plot data across all fires. Accuracy metrics, error matrices, and classification thresholds for the presence or absence of delayed mortality were averaged over all runs. Using the mean NBR decline threshold identified above, we generated binary maps of predicted delayed mortality for each of the six study fires to quantify the spatial extent of delayed mortality.

We then used the lm function in R (R Core Team 2022) to perform linear regression and assess the relationship of NBR decline with both canopy mortality based on the change in live tree cover and the number of trees as metrics of the magnitude of delayed mortality. We also assessed the relationship between canopy mortality and the number of trees that died to evaluate their consistency as metrics of delayed mortality.

Extent and magnitude of delayed mortality

We quantified the extent of NBR decline in each fire and forest type (Table 2; Simpson 2021) based on the area of pixels in which NBR decline exceeded the classification threshold for the presence of delayed mortality. To quantify cumulative shifts in RdNBR distributions between the 1-year immediate and 5-year delayed conditions as a landscape-scale indicator of the magnitude of delayed mortality, we calculated severity metrics for each fire and forest type following Lutz et al. (2011). This method converts a cumulative distribution of RdNBR values into a single value that can be used to compare distributions between two or more events.

Effects of delayed mortality on landscape patterns of burn severity

Immediate and delayed RdNBR were classified with the following thresholds based on the percent of basal area mortality following Reilly et al. (2017): unburned/very low (10%), low (< 25%), moderate (25–75%), and high (> 75%). We compared the size distribution for unburned/very low-severity patches and high-severity patches with the PyLandStats package (Bosch 2019) between immediate and delayed maps across all fires combined. We assessed shifts in the equality of area in each size class using the Gini coefficient which ranges from zero (perfect equality of area among patch size classes) to one (perfect inequality of area among patch size classes) using the DescTools package (Signorell 2023) in R.

Results

Validation

We observed NBR decline and delayed mortality across all study fires, although the extent and magnitude varied considerably (Fig. 3). NBR decline was widespread, occurring in 95% of plots with observed delayed mortality and in 54% of plots without observed mortality, although the magnitude of decline was consistently higher in plots that experienced delayed mortality (203 ± 109) than those that did not (44 ± 65) (Fig. 4).

Five-year NBR decline for the six study fires and examples of corresponding NAIP imagery highlighting areas with visible delayed mortality. NAIP imagery is visualized in false-color infrared, where live tree canopies appear red due to high near-infrared reflectance. Missing data within fire perimeters represents masked non-forest cover or salvage logging in white

A threshold of 105 ± 5 NBR decline classified delayed mortality presence in our test plots with 83% ± 2 overall accuracy (Table 3, Fig. S2). The proportion of mapped mortality that was correctly identified, or user’s accuracy, was 84 ± 3%. The proportion of all mortality that was mapped, or producer’s accuracy, was 83 ± 3%. Errors of commission—plots with NBR declines greater than 105 and no observed mortality—accounted for 8% of all plots, of which one third had no live trees in the year following fire. Errors of commission—plots with no canopy loss that exceeded the 105 NBR decline threshold—accounted for 12% of the total plots. On the other hand, 9% of all plots experienced some level of tree mortality without meeting the NBR decline threshold—errors of omission. The magnitude of mortality was also generally lower in these plots, with two or fewer trees dying in 71% of cases, compared to 33% across all mortality plots. Overall, plots with NBR decline over the 105 threshold were 23 times more likely to experience delayed mortality than those below the threshold (p < 0.001).

Both canopy mortality (r2 = 0.50, p < 0.001; Fig. 5) and the number of trees that died (r2 = 0.47, p < 0.001; Fig. S3) were significantly correlated with the magnitude of NBR decline between year-1 post-fire and the 5-year minimum NBR composite value. There was also a significant positive relationship between canopy mortality and the number of trees that died (r2 = 0.73, p < 0.001).

Regression for post-fire canopy mortality (%) and change in NBR derived from the minimum NBR of value for each pixel over 5 years following fire. Points are color-coded by a classification of RdNBR from the 1-year-post-fire basal area mortality where very low/unburned = 0–10%, low = 10–25%, moderate = 25–75%, and high = > 75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Note that points have been offset slightly along the x-axis to avoid overlapping points at the low end

Extent and magnitude of decline

Based on an NBR decline threshold of 105, delayed mortality affected a total of 7725 hectares (14%) across the six study fires (Table 1, Fig. 3). Excluding stand-replacing fire, the total extent of delayed mortality increased to 16%. The percentage of area burned experiencing delayed mortality varied from 6 to 24% among fires, (Table 1, Fig. 3) or 6 to 38% when excluding patches of stand-replacing fire. The change in the severity metric and percentage of area burned experiencing delayed mortality was generally greater in the wet and cold ecoregions of the western Cascades compared to the drier east Cascades and Klamath Mountains fires (Table 1). The 2013 Aspen fire in the Sierra Nevada of southern California was an exception to this pattern with a large increase in the severity metric and a relatively high percentage of area burned experiencing delayed mortality in a dry ecoregion. Delayed mortality generally affected a higher percentage of area burned in cold (22–41%) and wet (30%) forest types than in dry (1.7–19%) types which also generally experienced greater changes in the severity metric (Table 2).

Effects on cumulative landscape patterns of burn severity

The proportion of unburned/very low decreased an average of 38.1% (min = 8.8%, max = 75%) when considering delayed mortality and transitioned primarily to low or moderate severity in the delayed maps (Fig. 6, Fig. S4–S9). The Gini index for unburned/low-severity patches declined from 0.32 to 0.20 over the 5-year period, reflecting the loss of approximately 75% of the area of patches > 1000 ha (Fig. 7). Increases in the proportion of high severity averaged 16.2% of the immediate proportion when considering delayed mortality and ranged from 6.6 to 22.2% (Fig. 6). The Gini index for high-severity patches increased from 0.18 to 0.42 over the 5-year period reflecting an increase of 73% of the area burned in patches > 1000 ha (Fig. 7).

Changes in the distributions of RdNBR (left) and severity classes (right) from 1-year post-fire and 5-year delayed (minimum NBR composite) burn severity maps. Each distribution is summarized by a severity metric score (Lutz et al. 2011) where values closer to 1 indicate a higher severity distribution. Sankey diagrams depict pixel-scale shifts between immediate post-fire and delayed severity, with the proportion of the fire extent listed at the left and right, respectively

Size class distributions of unburned/ very low (< 10% mortality) and high (> 75% mortality) severity patches based on immediate (1-year post-fire) and delayed (5-year minimum NBR) burn severity maps for all six study fires. Inset maps depict example shifts between immediate and delayed severity maps

Discussion

Our method provides a generalizable approach to characterize and quantify delayed tree mortality following fire at landscape and regional scales. The area, magnitude, and effects of delayed mortality on landscape patterns of burn severity were highly idiosyncratic among fires but were generally greater in moist and cold forest types than in dry types. Spatial patterns of delayed mortality were highly clustered in localized patches, demonstrating a high degree of within landscape-scale variability in the effects of delayed mortality (Fig. 3). Cumulatively, shifts in spatial patterns of burn severity depict dynamic post-fire mosaics with the effects of tree-level delayed mortality scaling up to alter higher level landscape patterns of burn severity.

Post-fire NBR decline based on the 5-year minimum provides a method for mapping delayed mortality with high classification accuracy and was positively correlated with both canopy and tree mortality interpreted from NAIP as a metric of the magnitude of delayed mortality. Loss of canopy is the primary driver of changes in NBR post-fire (Fassnacht et al. 2021), and the relationship with canopy mortality in our study of delayed mortality was similar to field-based studies examining percent canopy mortality with NBR-based metrics of immediate burn severity (Miller et al. 2009). Minimum post-fire NBR composites captured post-fire spectral decline related to delayed mortality as well as other post-fire effects at the 30-m pixel scale. NBR declines > 105 were almost always (84%) associated with delayed mortality of one or more trees, and tree mortality in the absence of NBR decline > 105 was rare and typically restricted to mortality of one or two small, unhealthy trees (i.e., yellow canopy). On the other hand, low levels of NBR decline (< 105) were widespread even in the absence of tree mortality and may be related to other post-fire processes we observed at low levels of decline including partial canopy mortality and loss of dead needles, foliage, or small branches that were scorched but remained on the tree. In addition, spectral decline could also result from increased exposure of mineral soil and shadows (Fassnacht et al. 2021). In some cases, spectral decline below our mortality threshold may still indicate ecologically relevant delayed fire effects that could reduce photosynthetic capacity or resilience to pests or drought in the future and possibly lead to mortality beyond our 5-year window.

Both the extent and magnitude of delayed mortality varied among the six study fires (Table 1, Fig. 3). The effects of delayed mortality were consistently greater in the western Cascades than in other ecoregions despite post-fire climatic conditions characterized by normal or above-normal summer precipitation and cooler than normal summer temperatures following two of the three fires (Fig. S1). Moist and cold forest types in this ecoregion experienced higher levels of initial burn severity and are composed of less fire-resistant tree species (e.g., Abies spp., Tsuga spp.) with the exception of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) (Stevens et al. 2020), thus these forest types may be more vulnerable to first-order fire effects such as crown scorch which are strong predictors of delayed mortality in field studies (Cansler et al. 2020). The effects of delayed mortality were generally lower and more variable in dry ecoregions where fires were less severe and dominant tree species [e.g., Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa)] are more resistant to fire with the exception of grand fir (Abies grandis) and white fir (Abies concolor). Delayed mortality was notably high in the 2013 Aspen fire which burned during an exceptional period of drought and beetle-related tree mortality between 2012 and 2015 in the Sierra Nevada (Fettig et al. 2019). This highlights the potential for second-order fire effects (e.g., beetles and climate) which can cause substantial amounts of post-fire delayed mortality (van Mantgem et al. 2013; Hood et al. 2018). The generality of these patterns based on six fires remains to be seen, but our results provide some basic hypotheses to be tested across a larger sample of fires in future work. Our approach has great potential to complement existing tree-level research, however accurate mapping of salvage logging at large scales will be necessary prior to expanding across more fires at broader spatial and temporal scales.

Landscape-scale changes in classified burn severity maps depict dynamic post-fire mosaics as a result of delayed tree mortality that are likely to negatively affect forest resilience and further exacerbate habitat loss for fire-sensitive species. High-severity patches increased in size, reflecting both expansion of patches and losses of non-stand-replacing patches (e.g., low or moderate) within high-severity patches. An increase in high-severity patch size means seeds will have greater distances to travel for recolonization of severely burned patches, while loss of patches of legacy trees within severely burned patches will reduce propagule pressure from local seed sources. Declines in the area and size of very low-severity/unburned patches may also negatively affect species that rely on fire refugia for persistence or are sensitive to higher levels of burn severity (Krawchuk et al. 2020) as smaller, more fragmented patches will potentially have reduced ecological function as refugia.

While our method is generalizable across fires and forest types, it is also subject to similar uncertainties and limitations of immediate burn severity maps (Harvey et al. 2019; Furniss et al. 2020; Saberi et al. 2022). The resolution of Landsat imagery is coarser than an individual tree in most cases and limited to either mapping presence or absence and estimating stand-level mortality within a 900-m2 pixel. Additionally, NBR recovery post-fire can be rapid, with an average of 40% recovery of pre-fire NBR by 5 years (Bright et al. 2019). Accordingly, our method likely underestimates mortality in cases where much of the canopy was removed and post-fire spectral trajectories are dominated by the response of understory vegetation or resprouting trees (e.g., hardwoods). A final caveat is the potential for “background” or non-fire-induced tree mortality to also affect NBR decline, something that we currently do not account for. More field-based observations across a broad geography and diversity of forest types will provide a better understanding of the limitations and increase confidence in the method with additional validation.

Conclusions

Our study provides a novel way to incorporate delayed tree mortality into burn severity maps based on post-fire NBR decline and demonstrates that tree-level delayed mortality scales up to alter higher-level landscape patterns of burn severity. Differences between burn severity maps from 1 and 5 years post-fire reveal dynamic post-fire burn mosaics resulting from delayed tree mortality, with variability among fires reflecting a range of potential drivers. Assessing the effects, trends, and drivers of delayed mortality is possible in future studies and can provide a complementary understanding of delayed mortality to that derived from field studies. Application in future studies can inform post-fire restoration, refine mapping of unburned areas and fire refugia, update estimates of carbon and habitat loss from fire, and provide a more comprehensive assessment and understanding of landscape and regional-scale fire effects and trends.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets involved in this study are publicly available or available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Angers, V.A., S. Gauthier, P. Drapeau, K. Jayen, and Y. Bergeron. 2011. Tree mortality and snag dynamics in North American boreal tree species after a wildfire: a long-term study. International Journal of Wildland Fire 20: 751–763.

Barker, J.S., A.N. Gray, and J.S. Fried. 2022. The effect of crown scorch on post-fire delayed mortality are modifed by drought exposure in California (USA). Fire 5: 21.

Barlow, J., C.A. Peres, B.O. Lagan, and T. Haugaasen. 2003. Large tree mortality and the decline of forest biomass following Amazonian wildfires. Ecology Letters 6: 6–8.

Bosch, M. 2019. PyLandStats: an open-source pythonic library to compute landscape metrics. PLoS One 14: e0225734.

Bright, B.C., A.T. Hudak, R.E. Kennedy, J.D. Braaten, and A.H. Khalyani. 2019. Examining post-fire vegetation recovery with Landsat time series analysis in three western North American forest types. Fire Ecology 15: 8.

Cansler, C.A., and D. McKenzie. 2012. How robust are burn severity indices when applied in a new region? Evaluation of alternate field-based and remote sensing methods. Remote Sensing 4: 456–483.

Cansler, C.A., S.M. Hood, P.J. van Mantgem, and J.M. Varner. 2020. A large database supports the use of simple models of post-fire tree mortality for thick-barked conifers, with less support for other species. Fire Ecology 16: 25.

Catry, F.X., F. Rego, F. Moreira, P.M. Fernandes, and J.G. Pausas. 2010. Post-fire tree mortality in mixed forests of central Portugal. Forest Ecology and Management 260: 1184–1192.

Cocke, A.E., P.Z. Fule, and J.E. Crouse. 2005. Comparison of burn severity assessments using differenced normalized burn ratio and ground data. International Journal of Wildland Fire 14: 189–198.

Collins, L., P. Griffoen, G. Newell, and A. Mellor. 2018. The utility of Random Forests for wildfire severity mapping. Remote Sensing of Environment 216: 374–384.

Dwomoh, F.K., and M.C. Wimberly. 2017. Fire regimes and forest resilience: alternative vegetation states in the West African tropics. Landscape Ecology 32: 1849–1865.

Eidenshink, J., B. Schwind, K. Brewer, Z.-L. Zhu, B. Quayle, and S. Howard. 2007. A project for monitoring trends in burn severity. Fire Ecology 3: 3–21.

Fassnacht, F.E., E. Schmidt-Riese, T. Kattenborn, and J. Hernández. 2021. Explaining Sentinel 2-based dNBR and RdNBR variability with reference data from the bird’s eye (UAS) perspective. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 95: 102262.

Fettig, C.J., L.A. Mortenson, B.M. Bulaon, and P.B. Foulk. 2019. Tree mortality following drought in the central and southern Sierra Nevada, California, U.S. Forest Ecology and Management 432: 164–178.

Furniss, T.J., V.R. Kane, A.J. Larson, and J.A. Lutz. 2020. Detecting tree mortality with Landsat-derived spectral indices by examining uncertainty. Remote Sensing of Environment 237: 111497.

Gorelick, N., M. Hancher, M. Dixon, S. Ilyushchenko, D. Thau, and R. Moore. 2017. Google earth engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 202: 18–27.

Guo, L., S. Li, Z. Wu, R.A. Parsons, S. Lin, B. Wu, and L. Sun. 2022. Assessing spatial patterns and drivers of burn severity in subtropical forests in Southern China based on Landsat. Forest Ecology and Management 524: 120515.

Harvey, B.J., R.A. Andrus, and S.C. Anderson. 2019. Incorporating biophysical gradients and uncertainty into burn severity maps in a temperate fire-prone forested region. Ecosphere 10 (2): e02600. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2600.

Hood, S.M., and B. Bentz. 2007. Predicting postfire Douglas-fir beetle attacks and tree mortality in the northern Rocky Mountains. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 37: 1058–1069.

Hood, S.M., J.M. Varner, P.J. van Mantgem, and C.A. Cansler. 2018. Fire and tree death: Understanding and improving modeling of fire-induced tree mortality. Environmental Research Letters 13: 113004.

Key, C.H., Benson, N.C. 1999. The Normalized Burn Ratio, a Landsat TM radiometric index of burn severity incorporating multi-temporal differencing (http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/research/nbr.htm).

Krawchuk, M.A., G.W. Meigs, J. Cartwright, J.D. Coop, R. Davis, A. Holz, C. Kolden, and A.J.H. Meddens. 2020. Disturbance refugia within mosaics of forest fire, drought, and insect outbreaks. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 18: 235–244.

Lesmeister, D.B., R.J. Davis, S.G. Sovern, and Z. Yang. 2021. Northern spotted owl nesting forests as fire refugia: A 30-year synthesis of large wildfires. Fire Ecology 17: 32.

Lutz, J.A., C.H. Key, C.A. Kolden, J.T. Kane, and J.W. van Wagtendonk. 2011. Fire frequency, area burned, and severity: a quantitative approach to defining a normal fire year. Fire Ecology 7: 51–65.

Meyer, M.D., J.W. Long, and H.D. Safford. 2021. Postfire restoration framework for national forests in California. Gen. Tech. Report PSW-GTR-270, 204. Albany, CA: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station.

Miller, J.D., and A.E. Thode. 2007. Quantifying burn severity in a heterogeneous landscape with a relative version of the delta normalized burn ratio (dNBR). Remote Sensing of the Environment 109: 66–80.

Miller, J.D., and S.R. Yool. 2002. Mapping forest post-fire canopy consumption in several overstory types using multi-temporal Landsat TM and ETM data. Remote Sensing of Environment 82: 481–496.

Miller, J.D., E.E. Knapp, C.H. Key, C.N. Skinner, and C.J. Isbell. 2009. Calibration and validation of the relative differenced Normalized Burn Index (RdNBR) to three measures of fire severity in the Sierra Nevada and Klamath Mountains, California, USA. Remote Sensing of Environment 113: 645–656.

Palm, E.C., M.J. Suitor, K. Joly, J.D. Herriges, A.P. Kelly, D. Hervieux, K.L.M. Russell, T.W. Bentzen, N.C. Larter, and M. Hebblewhite. 2022. Increasing fire frequency and severity will increase habitat loss fri a boreal forest indicator species. Ecological Applications 32: e2549.

Parks, S.A., G.K. Dillon, and C. Miller. 2014. A new metric for quantifying burn severity: the relativized burn ratio. Remote Sensing 6: 1827–1844.

Pedregosa, F., G. Varoquaux, A. Gramfort, V. Michel, B. Thirion, O. Grisel, M. Blondel, P. Prettenhofer, R. Weiss, V. Dubourg, J. Vanderplas, A. Passos, D. Cournapeau, M. Brucher, M. Perrot, and É. Duchesnay. 2011. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 12: 2825–2830.

R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

Reilly, M.J., C. Dunn, G. Meigs, T.A. Spies, R. Kennedy, J. Bailey, and K. Briggs. 2017. Contemporary patterns of fire extent and severity in forests of the Pacific Northwest. Ecosphere 8 (3): e01695. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1695.

Robbins, Z., E.L. Loudermilk, M.J. Reilly, J. O’Brien, K. Jones, C. Gerstle, and R. Scheller. 2022. Delayed fire mortality has long-term ecological effects across the Southern Appalachian landscape. Ecosphere 13: e4153.

Saberi, S.J., M.C. Agne, and B.J. Harvey. 2022. Do you CBI what I see? The relationship between composite burn index and quantitative measures of burn severity varies across gradients of forest structure. International Journal of Wildland Fire 31: 112–123.

Schwilk, D.W., E.E. Knapp, S.M. Ferrenberg, J.E. Keeley, and A.C. Caprio. 2006. Tree mortality from fire and bark beetles following early and late season prescribed fires in a Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forest. Forest Ecology and Management 232: 36–45.

Signorell, A. 2023. DescTools: Tools for Descriptive Statistics. Retrieved from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=DescTools.

Simpson, M. 2021. Developer of the forest vegetation zone map. Ecologist, Central Oregon Area Ecology and Forest Health Program. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Bend, Oregon. Available at: https://ecoshare.info/products/potential-natural-vegetation-maps.

Soverel, N.O., D.D.B. Perrakis, and N.C. Coops. 2010. Estimating burn severity from Landsat dNBR and RdNBR indices across western Canada. Remote Sensing of Environment 144: 1896–1909.

Stevens, J.T., M.M. Kling, D.W. Schwilk, J.M. Varner, and J.M. Kane. 2020. Biogeography of fire regimes in western U.S. conifer forests: a trait-based approach. Global Ecology and Biogeography 29: 944–955.

van Mantgem, P.J., N.L. Stephenson, E. Knapp, J. Battles, and J.E. Keeley. 2011. Long-term effects of prescribed fire on mixed conifer forest structure in the Sierra Nevada California. Forest Ecology and Management 261: 989.

van Mantgem, P.J., J.C.B. Nesmith, M. Keifer, E.E. Knapp, A. Flint, and L. Flint. 2013. Climatic stress increases forest fire severity across the western United States. Ecology Letters 16: 1151–1156.

Wimberly, M.C., and M.J. Reilly. 2007. Assessment of fire severity and species diversity in the southern Appalachians using Landsat TM and ETM+ imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 108: 189–197.

Zhao, B., Q. Zhuang, N. Shurpali, K. Köster, F.M. Berninger, and Pumpanen. 2021. North American boreal forests are a large carbon source due to wildfires from 1986 to 2016. Scientific Reports 11: 7723.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Harold Zald, Sebastian Busby, and two anonymous reviewers for constructive reviews. Funding was provided by the USDA Washington Office through the Right Seed, Right Place project. Research was supported in part by an appointment to the United States Forest Service Research Participation Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy (DOE) and USDA.

Funding

This research was funded by the USDA Forest Service Washington Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR wrote the original draft of the manuscript and conceived of the methodology. All authors contributed to methodology, data processing, and analysis. All authors assisted with revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Departure from the 30-year (1991-2021) average of mean temperature, summer precipitation, and vapor pressure deficit, averaged over five years post-fire from PRISM data (Daly et al. 2008). Figure S2. Classification accuracy for delayed mortality by fire, and cumulatively. The same threshold of 105 NBR decline was used to classify delayed mortality across fires. Figure S3. Regression for tree mortality (number of trees dying) and change in NBR derived from the minimum NBR of value for each pixel over five years following fire. Points are color-coded by a classification of RdNBR from the one year-postfire basal area mortality where: very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Note that points have been offset slightly along the x-axis to avoid overlapping points at the low end. Figure S4. Burn severity maps based on immediate and delayed tree mortality in the 2013 Aspen Fire (7,672 ha) in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. Maps are classified based on RdNBR thresholds of tree basal area mortality where very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Figure S5. Burn severity maps based on immediate and delayed tree mortality in the 2008 Ukonom Fire (14,703 ha) in the Klamath Mountains of California. Maps are classified based on RdNBR thresholds of tree basal area mortality where very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Figure S6. Burn severity maps based on immediate and delayed tree mortality in the 2012 Table Mountain Fire (22,262 ha) in the Eastern Cascade Mountains of Washington. Maps are classified based on RdNBR thresholds of tree basal area mortality where very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Figure S7. Burn severity maps based on immediate and delayed tree mortality in the 2012 Cascade Creek Fire (7,758 ha) in the Western Cascade Mountains of Oregon. Maps are classified based on RdNBR thresholds of tree basal area mortality where very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Figure S8. Burn severity maps based on immediate and delayed tree mortality in the 2012 Dollar Lake Fire (2,459 ha) in the Western Cascade Mountains of Oregon. Maps are classified based on RdNBR thresholds of tree basal area mortality where very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017). Figure S9. Burn severity maps based on immediate and delayed tree mortality in the 2012 Mother Lode Fire (1,163 ha) in the Western Cascade Mountains of Oregon. Maps are classified based on RdNBR thresholds of tree basal area mortality where very low/unburned=0-10%, low=10-25%, moderate=25-75%, high=>75% (Reilly et al. 2017).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reilly, M.J., Zuspan, A. & Yang, Z. Characterizing post-fire delayed tree mortality with remote sensing: sizing up the elephant in the room. fire ecol 19, 64 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00223-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00223-1