Abstract

Backgrounds

Vaccine acceptance varies across countries, generations, and the perceived personality of individuals. Investigating the knowledge, beliefs, and acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines among individuals is vital to ensuring adequate health system capacity and procedures and promoting the uptake of the vaccines.

Results

A cross-sectional study was conducted from August 2021 to January 2022 in Saudi Arabia. The study included 281 residents to estimate their acceptance to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Around 70% of the included participants had a moderate to high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate during the data collection period. The risk increases to about two folds among undergraduates [OR 1.846 (1.034–3.296), p value = 0.036)] and increases to four folds among non-employed [OR 3.944 (2.310–6.737), p value = 0.001]. About 78% of participants with high and 44% with low COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (p value = 0.001) believed the vaccines were safe and effective. The belief that COVID-19 disease will be controlled within two years increased the risk for low vaccine acceptance by about two folds [OR 1.730 (1.035–2.891), p value = 0.035]. Good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccination significantly affected the acceptance rate (p value = 0.001).

Conclusions

Several factors affect the intention of individuals to receive vaccines. Therefore, building good knowledge and health literacy through educational intervention programs, especially vaccine safety and effectiveness, is important for successful vaccination campaigns among the general population and ensuring control of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vaccine acceptance varies across countries, generations, and the perceived personality of individuals (Habersaat and Jackson 2020; Wi Nguyen et al. 2011; La et al. 2931). Numerous studies have reported on the various aspects of new vaccine acceptance, including demographics and geographical disparities (Larson et al. 2018; Xiao and Wong 2020; Gidengil et al. 2012). A multinational survey documented by Lazarus et al. demonstrated that new vaccine acceptance in more than 18 nations varied from almost 90% to < 55% (Setbon and Raude 2010; Reiter et al. 2020; Harapan et al. 2020; Lazarus et al. 2021). The acceptance rate was 64% in the United States (US) (Horney et al. 2010), 56% in the United Kingdom (UK) (Rubin et al. 2010), 60% in Hong Kong (Chan et al. 2015), and 60% in China (Wu et al. 2018).

Concerns about vaccination need to be thoroughly understood, namely the safety and usefulness of the vaccine, knowledge, misconceptions, and confidence in the health system. Knowledge is essential to understanding pandemic hazards. Misinformation could lead to the general decline of uptake of new vaccines and jeopardize health authorities' response to the existing situation (Halpin and Reid 2022).

According to experts, at least 55% of the population should be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity against COVID-19 (Loomba et al. 2021).

Effective COVID-19 vaccination community interventions could improve the public's understanding and confidence in the vaccines and enhance their acceptance (Setbon and Raude 2010). Popular news media content should be reviewed for the most delinquent facts about COVID-19 vaccination.

Despite the ability of television and social media to rapidly revamp the community's information, nevertheless, the general awareness of COVID-19 vaccines remains low (Wang et al. 2020a).

Therefore, exploring the knowledge, beliefs, and acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines among individuals is vital to guarantee appropriate health system capacity and procedures, improving society's trust towards vaccination.

Methods

Study design and study participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted from August 2021 to January 2022 in Saudi Arabia. The sample size was calculated using the Cochran formula: (n = Z2 P (1- P)/d2). Where (Z) is the Standard normal variable od 1.96 at a 95% confidence interval, (n) is the minimum sample size required, P is the hypothesized proportion of acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine among the population, considered 40%, and d = acceptable margin of error, considered as 0.05. Accordingly, the estimated a minimum sample size was 384 subjects. However, it was challenging to collect the required sample, so we increased the margin of error to 0.06, and the required sample size was reduced to 256. The phone numbers of the included subjects were obtained from the 937 Medical Call Center (telemedicine service) using a systematic random sampling technique. Study participants had the following inclusion criteria: Saudi/non-Saudi individuals, males /females, vaccinated/non-vaccinated, aged 18 years and above, and responded to the questionnaire during the study period.

Data collection

The researchers designed a new Vaccine Acceptability Questionnaire (VAQ) which experts reviewed for the validity and reliability of all its items. The basis of designing the VAQ was to develop straightforward, precise questions that focused on COVID-19 vaccines compared to some previously published surveys used to assess the COVID-19 vaccines' acceptability (Loomba et al. 2021; Setbon and Raude 2010).

The VAQ consists of 31 questions under three items: underlying factors, knowledge, and beliefs that determine the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines. The VAQ was based on a 14-point score that ranged from 0 to 14. A score of 11–14 points was = high acceptance, 8–10.9 points = moderate acceptance, 5–7.9 = low acceptance, and less than 5 points = very low acceptability. The questionnaire was shared with the study participants through Short Message Service (SMS).

Ethical consideration

Approval for the study was given by MOH, Institutional Review Board (IRB), Saudi Arabia (IRB log No. 21–78M). The electronic questionnaire included a note stating that responding to the questionnaire was considered an acceptance to participate in the study. The data will not be used for purposes other than the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed using SPSS package version 24 with a level of significant difference at a p value < 0.05. The frequency of vaccine acceptability among studied subjects was determined. Factors associated with vaccine acceptability were studied using appropriate tests.

Results

The study included 281 Saudi residents to evaluate their acceptance to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Their mean age was 34.4 ± 9.7 years, and 47% were female. The majority of the included study participants were undergraduates (68%), employed (60%), and had received at least one dose of any COVID-19 vaccines (95%).

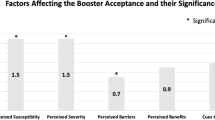

Table 1 explains the acceptability rate among studied residents relative to their background variables. Around 70% of the included participants had high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Most participants with lower vaccine acceptance were females (56.5%), undergraduates (76.5%), and non-employed (60.0%). Female gender was a risk for low vaccine acceptance by about 1.5 folds [OR 1.766 (1.056–2.952), p value = 0.029]. The risk was about two folds among undergraduates [OR 1.846 (1.034–3.296), p value = 0.036)] and four folds among non-employed participants [OR 3.944 (2.310–6.737), p value = 0.001].

Almost all residents with high vaccine acceptance (99.5%) received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and only 9.2% had previous COVID-19 infection following vaccination. The SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination increases the risk of low vaccine acceptance by more than 2.5 folds compared to non-infected people [OR 2.657 (1.304–5.410, p value = 0.007] (see Table 2).

The participants' perception of safety and efficacy significantly affected vaccine acceptance. The group with high acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine believed it was safe and more effective than the group with low acceptance (78% vs. 44%, p value < 0.001).

Conversely, the belief that COVID-19 disease will be controlled within two years or more increased the risk for low vaccine acceptance among participants by about two folds [OR + 1.730 (1.035–2.891), p value = 0.035]. Good knowledge of COVID-19 vaccination significantly affected the acceptance rate (p value = 0.001) (see Table 3).

Table 4 reveals the acceptability rate of COVID-19 vaccination among studied residents relative to their source of knowledge.

The group with high acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine used official sources for vaccine knowledge, including Saudi Ministry of Health (SMOH) news and health care providers' advice than the group with low acceptance (66% vs. 63% and 54% vs. 44%, respectively).

Discussion

It is essential to ensure the availability and efficacy of vaccines to control the COVID-19 pandemic successfully. Meanwhile, health authorities should ensure community trust and acceptance of the vaccine. Any hesitation and vaccination refusal could hinder the healthcare system's ability to control the pandemic.

The current study investigated factors associated with vaccine acceptance among studied residents. The reported background variables associated with a low acceptability rate are low education, non-employment, and female gender. This finding was inconsistent with Nehal et al., who found that gender and education were not significant variables for vaccine acceptance (Nehal et al. 2021).

The present study showed that about 70% of the participants reported a moderate to high acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. Several other Saudi studies were almost in line with our results, which showed that 62–71% of Saudi citizens and Saudi residents have a good acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines (Narapureddy et al. 2021; Alqahtani 2021; Alshahrani et al. 2021; Maqsood et al. 2022; Al-Mohaithef and Padhi 2020; Fadhel 2021; Yahia et al. 2021; Elharake et al. 2021). However, Khalafalla et al. reported that 83.6% of Jazan University students were willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine, which was described as having a high acceptance rate compared to most studies conducted in Saudi Arabia (Khalafalla et al. 2022). Despite that, the results revealed by Khalafalla et al. could not reflect the general population as they included a very specific group of people.

Nevertheless, a systematic review of 33 countries found that vaccine acceptance varies between countries with different socio-economic status. Low acceptance was reported in countries such as Kuwait (23.6%) and Jordan (28.4%), and moderate acceptance in countries such as Italy (53.7%), Poland (56.3%), and Russia (54.9%). In contrast, some countries exhibited high acceptance, especially in East Asia, such as Indonesia (93.3%), China (91.3%), and Malaysia (94.3%) (Sallam 2021).

Despite the misinformation and rumors about COVID-19 vaccines repeatedly shared on social media platforms (Puri et al. 2020), about half (51%) of the studied participants depended on social media as their primary source of knowledge. A study reported that vaccine hesitancy and refusal are associated with misinformation on social media (Bianco et al. 2019). This finding reflects the importance of educational interventions to address misinformation about vaccines.

Likewise, participants' perception of the vaccine as safe and effective was another significant factor in the high acceptance rate among studied participants. Conversely, the belief that COVID-19 disease will be controlled within two years and COVID-19 infection after vaccination were inversely associated with the vaccine acceptance rate. Similarly, a study in China found that 48% of respondents postponed vaccination because they were concerned about the safety of vaccines (Wang et al. 2020b). Also, a United States study found that 89% of participants assumed that COVID-19 vaccines could have some side effects which affected vaccine acceptance (Callaghan et al. 2020).

While a survey in Bangladesh found that about a quarter of participants thought that COVID-19 was safe, only 60% were willing to be vaccinated, and about two-thirds will recommend it to family and friends (Islam et al. 2021). It is believed that misinformation and lack of data on the seriousness of incidence and mortality of COVID-19 disease may reduce concerns about vaccine acceptability (Geoghegan et al. 2020).

Inconsistent with the current study findings, Elhadi et al. found that having a family member or friend infected with COVID-19 was positively associated with the likelihood of vaccine acceptance (OR 1.09 [1.02, 1.18]). While they found that having a friend or family member who died due to COVID-19 was negatively associated with it (OR 0.89 [0.84, 0.97]) (Elhadi et al. 2021).

Likewise, a meta-regression analysis conducted by Kukreti et al. found that a COVID-19 death rate of 400 per million population or higher was significantly associated (p value = 0.02) with the willingness rate for vaccination (Kukreti et al. 2022).

The variation in the acceptability rate between different studies reflects the interaction between vaccine perception and background variables, namely age groups and educational levels.

Conclusions

Several factors affect the intention of individuals to receive vaccines. Therefore, building good knowledge and health literacy through educational intervention programs, especially vaccine safety and effectiveness, is important for successful vaccination campaigns among the general population and ensuring control of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SMOH:

-

Saudi Ministry of Health

- SMS:

-

Short Message Service

- TV:

-

Television

- US:

-

United States

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- VAQ:

-

Vaccine Acceptability Questionnaire

References

Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK (2020) Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc 13:1657

Alqahtani YS (2021) Acceptability of the COVID-19 vaccine among adults in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study of the general population in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 10(1):41

Alshahrani SM, Dehom S, Almutairi D, Alnasser BS, Alsaif B, Alabdrabalnabi AA, Bin Rahmah A, Alshahrani MS, El-Metwally A, Al-Khateeb BF, Othman F (2021) Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study using a web-based survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother 17(10):3338–3347

Bianco A, Mascaro V, Zucco R, Pavia M (2019) Parent perspectives on childhood vaccination: How to deal with vaccine hesitancy and refusal? Vaccine 37(7):984–990

Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, Hotez PJ, Strych U, Dor A, Franklin Fowler E, Motta M. Correlates and Disparities of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy (August 5, 2020). Available at SSRN 3667971.

Chan EY, Cheng CK, Tam GC, Huang Z, Lee PY (2015) Willingness of future A/H7N9 influenza vaccine uptake: a cross-sectional study of Hong Kong community. Vaccine 33(38):4737–4740

Elhadi M, Alsoufi A, Alhadi A, Hmeida A, Alshareea E, Dokali M, Abodabos S, Alsadiq O, Abdelkabir M, Ashini A, Shaban A (2021) Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21(1):1–21

Elharake JA, Galal B, Alqahtani SA, Kattan RF, Barry MA, Temsah MH, Malik AA, McFadden SM, Yildirim I, Khoshnood K, Omer SB (2021) COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis 109:286–293

Fadhel FH (2021) Vaccine hesitancy and acceptance: An examination of predictive factors in COVID-19 vaccination in Saudi Arabia. Health Promot Int

Geoghegan S, O’Callaghan KP, Offit PA (2020) Vaccine safety: myths and misinformation. Front Microbiol 11:372

Gidengil CA, Parker AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ (2012) Trends in risk perceptions and vaccination intentions: a longitudinal study of the first year of the H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health 102(4):672–679

Habersaat KB, Jackson C (2020) Understanding vaccine acceptance and demand—and ways to increase them. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 63(1):32–39

Halpin C, Reid B (2022) Attitudes and beliefs of healthcare workers about influenza vaccination. Nurs Older People 34(1)

Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, Setiawan AM, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M (2020) Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health 8:381

Horney JA, Moore Z, Davis M, MacDonald PD (2010) Intent to receive pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccine, compliance with social distancing and sources of information in NC, 2009. PLoS ONE 5(6):e11226

Islam M, Siddique AB, Akter R, Tasnim R, Sujan M, Hossain S, Ward PR, Sikder M (2021) Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccinations: a cross-sectional community survey in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 21(1):1–1

Khalafalla HE, Tumambeng MZ, Halawi MH, Masmali EM, Tashari TB, Arishi FH, Shadad RH, Alfaraj SZ, Fathi SM, Mahfouz MS (2022) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy prevalence and predictors among the students of Jazan University, Saudi Arabia using the health belief model: a Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 10(2):289

Kukreti S, Rifai A, Padmalatha S, Lin CY, Yu T, Ko WC, Chen PL, Strong C, Ko NY (2022) Willingness to obtain COVID-19 vaccination in general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 12:5006

La VP, Pham TH, Ho MT, Nguyen MH, Nguyen KLP, Vuong TT, Tran T, Khuc Q, Ho MT, Vuong QH (2020) Policy response, social media and science journalism for the sustainability of the public health system amid the COVID-19 outbreak: the Vietnam lessons. Sustainability 12(7):2931

Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, Paterson P (2018) Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 14(7):1599–1609

Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A (2021) A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 27(2):225–228

Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek SJ, de Graaf K, Larson HJ (2021) Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav 5(3):337–348

Maqsood MB, Islam MA, Al Qarni A, Ishaqui AA, Alharbi NK, Almukhamel M, Hossain MA, Fatani N, Mahrous AJ, Al Arab M, Alfehaid FS (2022) Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and reluctance among staff working in public healthcare settings of Saudi Arabia: a multicenter study. Front Public Health 10

Narapureddy BR, Muzammil K, Alshahrani MY, Alkhathami AG, Alsabaani A, AlShahrani AM, Dawria A, Nasir N, Reddy LK, Alam MM (2021) COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: beliefs and barriers associated with vaccination among the residents of KSA. J Multidiscip Healthc 14:3243

Nehal KR, Steendam LM, Campos Ponce M, van der Hoeven M, Smit GS (2021) Worldwide vaccination willingness for COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines 9(10):1071

Puri N, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H, Gunaratne K (2020) Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother 16(11):2586–2593

Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML (2020) Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 38(42):6500–6507

Rubin GJ, Potts HW, Michie S (2010) The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technol Assess 14(34):183–266

Sallam M (2021) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 9(2):160

Setbon M, Raude J (2010) Factors in vaccination intention against the pandemic influenza A/H1N1. Eur J Pub Health 20(5):490–494

Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H (2020a) Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines 8(3):482

Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H (2020b) Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines (basel) 8(3):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8030482

Wi Nguyen T, Henningsen KH, Brehaut JC, Hoe E, Wilson K (2011) Acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine: a systematic review of surveys of the general public. Infect Drug Resist 4:197

Wu S, Su J, Yang P, Zhang H, Li H, Chu Y, Hua W, Li C, Tang Y, Wang Q (2018) Willingness to accept a future influenza A (H7N9) vaccine in Beijing. China Vac 36(4):491–497

Xiao X, Wong RM (2020) Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine 38(33):5131–5138

Yahia AI, Alshahrani AM, Alsulmi WG, Alqarni MM, Abdulrahim TK, Heba WF, Alqarni TA, Alharthi KA, Buhran AA (2021) Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy: a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Hum Vaccin Immunother 17(11):4015–4020

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mustafa Hassanein and Dr. Elfadil Elkajam (Assisting Deputyship for Primary Healthcare, Saudi Ministry of Health) for reviewing the VAQ and the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK and NR conceptualized the study. NR, AK, AH, and NM wrote the original draft preparation. NM, AF, AS, AK, AK, and KA helped to write and edit the review. NR, WA, AK, AF, and KA contributed in the resources (scholarly journal articles and research based reviews). AS, AK, WA, and AK organized the data collection process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for the study was given by MOH, Institutional Review Board (IRB), Saudi Arabia (IRB log No. 21–78M). The electronic questionnaire included a note stating that responding to the questionnaire was considered an acceptance to participate in the study. The data will not be used for purposes other than the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript, namely employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkattan, A., Radwan, N., Mahmoud, N. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: knowledge and beliefs. Bull Natl Res Cent 46, 260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00949-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00949-z