Abstract

Background

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale is a screening tool used to diagnose patients with chronic pelvic pain. Numerous articles demonstrated the efficacy of the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale, not only as a screening tool, but additionally for complete assessment and management process. Therefore, in this article we aim to translate the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale from English to Arabic and then to validate the translated version using an innovative technique that compares the original English version to a back-translated version.

Results

Using back-translation method, the comparability of the language and similarity of the interpretation for each item of Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale were validated. The back-translated version showed seemingly dependable results and demonstrates an almost identical meaning to the original English version. There was no difference found statistically in the median or mean scores for all items between the English and Arabic back-translated versions. The multi-staged process we followed thoroughly and the results obtained during this process ensured the validity of the Arabic version of the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale.

Conclusions

The current study provides that the Arabic version of Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale is proven to be a valid tool in the assessment of Arabic-speaking patients with painful bladder syndrome or interstitial cystitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Interstitial cystitis (IC) and painful bladder syndrome (PBS) are general terms that describe a chronic and devastating condition with an unidentified aetiology that affects both males and females, severely decreasing their quality of life (Marcu et al. 2018; Huffman et al. 2019). This condition encompasses a cluster of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) originating in the bladder, such as urgency and frequency that are associated with chronic pelvic pain lasting longer than six weeks. The classic symptoms include suprapubic pain, although patients sometimes report pain radiating to the groin, vagina, rectum and sacrum, and up to 60% of female patients report dyspareunia (Huffman et al. 2019; Daniels et al. 2018). The severity of symptoms varies among affected individuals and ranges from mild pain with urinary symptoms to severe, devastating pain that markedly reduces their quality of life, and increases in severity with disease progression (Huffman et al. 2019). The pain itself can result in a poor quality of life, but usually, other issues, such as LUTS, anxiety, stress and sleep deprivation, contribute to it (McKernan et al. 2020).

There are obvious variations and discrepancies between epidemiological studies that aim to estimate the prevalence of IC/PBS in populations (Huffman et al. 2019; Anger et al. 2022). This is mostly due to different definitions for the same condition, the lack of definitive diagnostic criteria and poor sampling methodologies (Skove et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2021; Malde et al. 2018). Furthermore, to date, there are no published studies that estimate the prevalence of IC/PBS in Saudi Arabia or any Arab country. In general, the literature shows a prevalence of IC/PBS ranging from 0.045 to 6.5% among women and 0.008% to 4.5% among men (Khullar et al. 2019).

Due to lack of a complete understanding of the aetiology of IC/PBS, an absence of definitive diagnostic tests and variations between definitions and diagnostic criteria in different guidelines, the diagnosis of IC/PBS has become a challenging process for clinicians (Lee et al. 2021; Malde et al. 2018; Khullar et al. 2019; Pape et al. 2019). However, for the initial investigation and evaluation of the patient’s complaints, all guidelines recommend a full analysis of the patient’s history and complaints, followed by a comprehensive physical examination and routine laboratory tests, such as urine analysis, culture and cytology to detect other possible causes of the patient’s current complaints (Pape et al. 2019; Tirlapur et al. 2013). The most important step in diagnosing IC/PBS is the comprehensive analysis of the patient’s complaints; hence, many screening tools have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of IC/PBS. One of the most widely used instruments is the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency (PUF) symptom scale (Lee et al. 2021; Parsons et al. 2002). The PUF symptom scale, attached as ‘Additional file 1’, was first introduced in 2002 by C. Lowell Parsons as a screening modality to detect IC/PBS in women with chronic pelvic pain and LUTS (Parsons et al. 2002). The scale consists of two scores: The first score measures the severity of the patient’s LUTS, pelvic pain and sexual intercourse-associated symptoms and ranges from 0 to 23 points. The second score measures how much the patient is troubled by these symptoms and ranges from 0 to 12 points. When these two scores are combined, the total PUF symptom score ranges from 0 to 35 points (Parsons et al. 2002; Rosenberg et al. 2007; Cheng et al. 2012). The PUF symptom scale has been validated using the intravesical potassium sensitivity test (PST); a higher score on the PUF symptom scale is associated with up to a 90% chance of a positive PST (Rosenberg et al. 2007; Cheng et al. 2012). The PUF symptom scale has been reported to be a useful tool for screening patients for IC, assessing the severity of their symptoms, following up on the success of symptom management and assessing patients for recurrence or progression of their symptoms. Additionally, it is a widely used tool among clinicians worldwide (Tirlapur et al. 2013; Cheng et al. 2012; Kushner and Moldwin 2006; Brewer et al. 2007). Thus, our aim in this paper is to translate and validate the original English PUF symptom scale to Arabic.

Methods

A written permission was initially obtained electronically from Professor C. Lowell Parsons to translate the PUF symptom scale from English to Arabic. The process was divided into two phases: (1) translation of the PUF symptom scale from English to Arabic and (2) validation of the original English version to a back-translated English version of the PUF symptom scale.

Phase 1: translation of the PUF symptom scale from English to Arabic

We recruited two independent, bilingual translators, certified by the American Translators Association (ATA), to translate the English version of the PUF symptom scale to Arabic using a forward-translation technique. Then, two bilingual expert clinicians, with Arabic as their native language who had completed their higher education in English-speaking Western countries, reviewed the two Arabic versions of the scale, thereby creating a third, (modified) version of it An Arabic teacher checked the latter version of the PUF symptom scale for phonation and grammatical errors, attached as 'Additional file 2'. Then a third, independent ATA-certified translator, fluent in English and Arabic, as well as medical terminology, translated the final Arabic version back to English, resulting in a back-translated English version.

Phase 2: validation of the original English version to a back-translated English version of the PUF symptom scale

A committee of thirty experts compared the back-translated and original English versions of the scale using the ‘Comparability/Interpretability Rating Sheet’ to ensure the quality of the translation (Sperber et al. 1994). Some of the experts were native English speakers, and some were native English speakers who were bilingual in Arabic and English. We ensured that all of them held higher education degrees in the field of medicine and/or English literature.

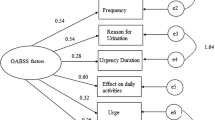

Sperber et al. (1994) were the first to describe this technique in 1994 to overcome some of the well-known pitfalls of translating questionnaires. Sperber argued that this technique could minimise methodological problems common to cross-cultural research by introducing an innovative step in the validation process (Fig. 1) (Sperber et al. 1994; Sperber 2004).

Results

This technique consisted of two subscales measuring the comparability of the language and the similarity of the interpretations. Each item was rated on a scale of 1 (extremely comparable/similar) to 7 (not at all comparable/similar) points for both subscales of the PUF symptom scale. Items with a mean score > 3 on the comparability subscale or > 2.5–3 the interpretability subscale were considered problematic and required a review (Sperber 2004).

Items’ ratings for language comparability had mean scores ranging from 1.3 (Standard Deviation (SD) 0.00) to 2.03 (SD 0.71) (Table 1). These scores indicated that the original English and back-translated English versions were extremely comparable in language and did not show discrepancies in meaning. Hence, revisions and reviews of this subscale were not required.

Items’ ratings for similarity of interpretation had mean scores ranging from 1.3 (SD 0.71) to 2.13 (SD 0.00), as shown in Table 2, implying that the experts thought the items of both versions had extremely similar meanings and that they understood the questions of both versions in the same way, with no discrepancies. Consequently, a re-evaluation was not required.

Discussion

The PUF symptom scale was introduced by C. Lowell Parsons in 2002, as a tool for the detection of IC (Parsons et al. 2002). At that time, the PUF symptom scale was validated using the intravesical PST (Parsons et al. 2002), which detects bladder epithelial abnormalities that are associated with IC (Parsons et al. 2002). A total of 382 patients were divided into three test groups and one control group; they were screened using both the PUF symptom scale and the PST (Parsons et al. 2002). This experiment showed a correlation between a high PUF symptom scale and a high likelihood of having a positive PST (Parsons et al. 2002). The PUF symptom scale has been used worldwide for screening IC/BPS in patients with chronic pelvic pain that is associated with urinary or sexual symptoms and for monitoring the treatment responses of patients already diagnosed with IC/PBS (Pape et al. 2019; Rosenberg et al. 2007; Cheng et al. 2012; Kushner and Moldwin 2006; Brewer et al. 2007).

There have been several successful attempts to translate the PUF symptom scale to different languages. Yet, there is no validated Arabic version of the PUF symptom scale. Therefore, we translated the PUF symptom scale to Arabic and validated its accuracy. As this Arabic version showed seemingly reliable results and almost identical meanings between the items on the original and back-translated versions, it can be considered a useful tool for urology and gynaecology patients in all Arabic-speaking countries, as well as Saudi Arabia.

Although the results obtained were within the acceptable range, a few points raised by some of the raters necessitated revisions. First, few of the English native speakers found that the original English version had some colloquial terms, i.e. ‘using the bathroom at night’. Those raters requested elaboration on the exact meaning of using the toilet to urinate, not to defecate. Thus, in the Arabic version, which was back-translated, we clarified the language, as shown in items 1, 2a and 2b (Table 1). Second, the Arabic word for perineum is not a common word used by the general public; therefore, a description was added to explain the anatomical location of the perineum, as shown in item 5 (Table 1).

Conclusions

The proposed Arabic version of the PUF symptom scale is considered to be valid and accurate version in meaning and interpretation of the English version. Therefore, it can be utilised in diagnosing and managing Arabic-speaking patients with IC/PBS. Moreover, it will aid in conducting further research projects concerning IC/PBS amongst Arabic-speaking patients.

Availability of data and materials

The translated and validated Arabic version of PUF patient symptom scale was attached to this manuscript as ‘Additional file 2’ and can be used without further requests.

Abbreviations

- IC/PBS:

-

Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- PUF:

-

Pelvic pain and urgency/frequency

- PST:

-

Potassium sensitivity test

- ATA:

-

American Translators Association

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Anger J, Dallas K, Bresee C, De Hoedt A, Barbour K, Hoggatt K et al (2022) National prevalence of IC/BPS in women and men utilizing veterans health administration data. Front Pain Res. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2022.925834

Brewer M, White W, Klein F, Klein L, Waters W (2007) Validity of pelvic pain, urgency, and frequency questionnaire in patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology 70(4):646–649

Cheng C, Rosamilia A, Healey M (2012) Diagnosis of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome in women with chronic pelvic pain: a prospective observational study. Int Urogynecol J 23(10):1361–1366

Daniels A, Schulte A, Herndon C (2018) Interstitial cystitis: an update on the disease process and treatment. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 32(1):49–58

Huffman M, Slack A, Hoke M (2019) Bladder pain syndrome. Prim Care Clin Off Pract 46(2):213–221

Khullar V, Chermansky C, Tarcan T, Rahnama’i M, Digesu A, Sahai A et al (2019) How can we improve the diagnosis and management of bladder pain syndrome? Part 1: ICI-RS 2018. Neurourol Urodyn. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24166

Kushner L, Moldwin R (2006) Efficiency of questionnaires used to screen for interstitial cystitis. J Urol 176(2):587–592

Lee J, Yoo K, Choi H (2021) Prevalence of bladder pain syndrome-like symptoms: a population-based study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e293

Malde S, Palmisani S, Al-Kaisy A, Sahai A (2018) Guideline of guidelines: bladder pain syndrome. BJU Int 122(5):729–743

Marcu I, Campian E, Tu F (2018) Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Semin Reprod Med 36(02):123–135

McKernan L, Bonnet K, Finn M, Williams D, Bruehl S, Reynolds W et al (2020) Qualitative analysis of treatment needs in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: implications for intervention. Can J Pain 4(1):181–198

Pape J, Falconi G, De Mattos Lourenco T, Doumouchtsis S, Betschart C (2019) Variations in bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (IC) definitions, pathogenesis, diagnostics and treatment: a systematic review and evaluation of national and international guidelines. Int Urogynecol J 30(11):1795–1805

Parsons C, Dell J, Stanford E, Bullen M, Kahn B, Waxell T et al (2002) Increased prevalence of interstitial cystitis: previously unrecognized urologic and gynecologic cases identified using a new symptom questionnaire and intravesical potassium sensitivity. Urology 60(4):573–578

Rosenberg M, Page S, Hazzard M (2007) Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in a primary care setting. Urology 69(4):S48–S52

Skove S, Howard L, Senechal J, Hoedt A, Bresee C, Cunningham T et al (2019) The misdiagnosis of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome in a VA population. Neurourol Urodyn 38(7):1966–1972

Sperber A (2004) Translation and validation of study instruments for cross-cultural research. Gastroenterology 126:S124–S128

Sperber A, Devellis R, Boehlecke B (1994) Cross-cultural translation. J Cross-Cult Psychol 25(4):501–524

Tirlapur S, Priest L, Wojdyla D, Khan K (2013) Bladder pain syndrome: validation of simple tests for diagnosis in women with chronic pelvic pain: BRaVADO study protocol. Reprod Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-61

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Parsons for providing us with his permission to start the translation process using PUF patient symptom scale.

Funding

There were no specific grants or funding for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BR analysed and evaluated experts data and a major contributor to the manuscript writing, drafting and editing, AN supervised the manuscript writing and drafting, AB proofread the manuscript and overall editing, and AAA contributed to the literature review, data analysis and manuscript writing. FM contributed to the literature review, background writing and manuscript drafting. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

A written consent was obtained by email from Professor Parsons on 28/12/2021 to use the English version of PUF symptom scale for Arabic translation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The original English version of pelvic pain and urgency/frequency (PUF) patient symptom scale as published by Parsons et al in 200212.

Additional file 2.

The translated and validated Arabic version of the pelvic pain and urgency/frequency (PUF) patient symptom scale.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rafi, B., Nassir, A., Baazeem, A. et al. Arabic translation and validation of Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency (PUF) Patient Symptom Scale. Bull Natl Res Cent 46, 251 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00942-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00942-6