Abstract

Background

We report an exceedingly rare case of bilateral external iliac artery pseudoaneurysms causing urinary obstruction and acute renal failure.

Case presentation

A young man presented with acute severe bilateral testicular pain radiating to the back. Clinical and radiological workup showed bilateral external iliac artery pseudoaneurysms, which caused bilateral ureterohydronephrosis due to urinary obstruction with subsequent renal failure. Management included immediate bilateral external iliac artery endovascular repair and bilateral ureterolysis using a retroperitoneal approach, with resolution of the obstruction and successful endovascular treatment of both pseudoaneurysms. The only identifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease was cocaine addiction.

Conclusions

This case highlights an unusual and severe clinical presentation of bilateral EIA pseudoaneurysms causing bilateral ureterohydronephrosis and subsequent renal failure. Awareness of this condition may help avoid misdiagnosis and delayed management, which is of utmost importance for a favorable outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pseudoaneurysms are usually caused by trauma, infection, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, or iatrogenic complications (Sueyoshi et al. 2005; Lazarides et al. 1991), with most cases remaining clinically silent. However, a few may become symptomatic, and patients might present with limb ischemia, leg edema, and subacute or acute hemorrhage. An unusual presentation of bilateral external iliac artery (EIA) pseudoaneurysms is reported here.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old man presented to the emergency department with acute severe bilateral testicular pain radiating to the back. The pain initiated during the night, awakening the patient and prompting medical attention. He described the pain as sharp and continuous, radiating to his lower back bilaterally with no worsening or alleviating factors. The patient had no history of trauma, underlying medical conditions, regular medications, or previous surgical procedures. Abnormal urinary symptoms were also ruled out.

On admission, he was hypotensive (100/60 mmHg) with normal heart rate and normal neurological status. Physical examination revealed mild dehydration, pale mucous membranes, and cool extremities. Peripheral pulse was symmetric in the lower and upper limbs. No heart murmurs, signs of pulmonary congestion or pleural effusion were observed. On abdominal palpation, a lower abdominal mass was noted with mild discomfort. No signs of acute peritonitis were present. Testicular examination was unremarkable.

Anemia (hemoglobin level of 7.6 g/dL and hematocrit of 24%) and acute renal failure (creatinine of 2.8 g/dL, normal blood urea with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 29 mL/min/1.73 m2) were observed. Testicular tumor markers were negative. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a retroperitoneal mass causing bilateral ureterohydronephrosis. All imaging studies were normal.

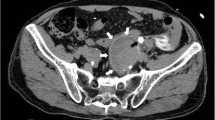

Even in the setting of acute renal failure, contrast-enhanced multiaxial tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was deemed necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. It revealed bilateral EIA pseudoaneurysms (Fig. 1A) causing moderate bilateral ureterohydronephrosis (Fig. 1B) with clear signs of contrast leakage from the right EIA pseudoaneurysm into the retroperitoneum, reflecting evidence of an acutely ruptured pseudoaneurysm associated with an ipsilateral retroperitoneal hematoma (Fig. 1C). These findings supported acute anemia and renal failure.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. Axial view showing bilateral large-diameter pseudoaneurysms of the external iliac arteries; A the arrowhead shows a pelvic hematoma with increased attenuation and the arrow shows a draping effect on the posterior external iliac wall. B axial view, demonstrating bilateral ureterohydronephrosis; C Coronal view, in which leakage of contrast is seen in the right side

The patient was blood typed, and saline expansion was performed. A left jugular vein catheter was placed in case of acute deterioration. The on-call vascular surgeon performed a bedside Doppler ultrasound of the iliac arteries revealing a turbulent flow with swirling motion pattern, also known as the “yin-yang sign,” in the right EIA, thus confirming the finding of a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the right EIA (Fig. 2).

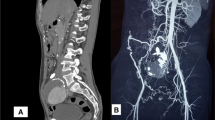

Due to the risk of ongoing bleeding, the patient underwent emergency endovascular repair of the bilateral EIA pseudoaneurysms (Fig. 3A, B, and C), ruptured on the right side (Fig. 3D), with the placement of bilateral 8 mm (in diameter) × 50 mm (in length) WALLGRAFT® endoprostheses (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). After angiographic confirmation of successful treatment, with no further bleeding or leakage (Fig. 3E and F), open inguinotomy was performed for ureterolysis and drainage of retroperitoneal hematoma.

A Preoperative 3D vessel reconstruction; B Intraoperative arteriogram of the iliac arteries; C Selective arteriogram of the left external iliac artery pseudoaneurysm, oblique view, arrow points the leakage; D Selective arteriogram of the right external iliac artery pseudoaneurysm showing contrast leakage (arrow) – with left endoprosthesis in place (*); E Control CT with no evidence of contrast leakage, a week later

Immediate post-decompression diuresis was observed, with substantial urine output (12 L) in the first 24 hours after the procedure. Creatinine peaked at 3.2 g/dL on postoperative day 1, and his renal function normalized after 1 week of follow-up. During this period, the patient was closely monitored for his hemodynamic condition and renal function recovery to prevent dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

Hematoma content and connective tissue removed from the perianeurysmal area were analyzed histopathologically and tested for bacteria and fungi. Serology for community-acquired infectious diseases, inflammatory laboratory tests and other specific rheumatological tests (antinuclear antibodies for systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune tests) were performed, and the patient was evaluated by a multidisciplinary panel of experts in the fields of vascular surgery, internal medicine, infectious disease, rheumatology, and urology. Laboratory results were within the normal range, and cultures were negative. The only identifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease was cocaine addiction (for the past 2 years).

Conclusion

Bilateral ureteral obstruction and acute renal failure due to bilateral iliac artery conditions is a very rare entity, with only a few reported cases (Wu and Ma 2019; Oliveira et al. 2018). This observation might be explained by the reported prevalence of this condition. The occurrence of iliac artery aneurysms associated with abdominal aortic aneurysms is relatively common, accounting for 10% to 20% of all aortic aneurysms (Uberoi et al. 2011). Isolated iliac artery aneurysms, however, are rare (0.4% to 1.9% of all intra-abdominal aneurysms) (Richardson and Greenfield 1988), with EIA aneurysms being even rarer (Uberoi et al. 2011) and mostly associated with a previous history of trauma or infection (Hussain and Aziz 2019; Krupski et al. 1998).

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of ruptured EIA pseudoaneurysms causing bilateral ureterohydronephrosis with subsequent renal failure. An unusual clinical presentation as acute severe bilateral testicular pain radiating to the back, compensated hypovolemic shock, acute anemia and acute kidney injury were the most remarkable early findings in this particular case.

Common underlying causes of pseudoaneurysm were excluded, and the only identifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease was cocaine addiction. This clinical presentation is worrisome, and we believe this case merits report because misdiagnosis might result in a significant delay in the treatment of a critical emergency condition. Hypovolemic shock may occur in case of rupture; therefore, prompt management is crucial with either an open or an endovascular approach. Endovascular intervention using a covered stent has the advantages of being less invasive and achieving faster bleeding control in most cases (Adovasio et al. 2003).

In the present case, relief of urinary obstruction was also necessary. Hematoma drainage using an open retroperitoneal approach and bilateral ureterolysis were required to resolve the ureteral entrapment caused by the inflammatory pseudoaneurysms. An open repair was also of interest in order to obtain material for histopathological analysis.

This case highlights an unusual and severe clinical presentation of bilateral EIA pseudoaneurysms causing bilateral ureterohydronephrosis and subsequent renal failure. Radiological workup showed a ruptured pseudoaneurysm on the right side although the patient was still on the compensated phase of hypovolemic shock. Awareness of this condition may help avoid misdiagnosis and delayed management, which is of utmost importance for a favorable outcome.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Adovasio R, Mucelli FP, Lubrano G et al (2003) Endovascular treatment of external iliac artery injuries after hip arthroplasty. J Endovasc Ther. https://doi.org/10.1583/1545-1550(2003)010<0672:ETOEIA>2.0.CO;2

Hussain AS, Aziz A (2019) Giant external iliac artery aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg 58:386.e1–386.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2018.11.012

Krupski WG, Selzman CH, Floridia R et al (1998) Contemporary management of isolated iliac aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70194-6

Lazarides MK, Arvanitis DP, Dayantas JN (1991) Latrogenic arterial trauma associated with hip joint surgery: an overview. Eur J Vasc Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-821X(05)80343-3

Oliveira M, Sousa C, Coentrão L (2018) Bilateral common iliac artery aneurysms as cause of renal failure. Intensive Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4936-4

Richardson JW, Greenfield LJ (1988) Natural history and management of iliac aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/0741-5214(88)90405-3

Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Nakashima K, Minami K, Hayashi K (2005) Visceral and peripheral arterial pseudoaneurysms. Am J Roentgenol. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.185.3.01850741

Uberoi R, Tsetis D, Shrivastava V et al (2011) Standard of practice for the interventional Management of Isolated Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 34:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-010-0055-0

Wu Z, Ma Y (2019) Acute kidney injury secondary to bilateral common iliac artery aneurysms. Intern Med J. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14225

Acknowledgements

We could not have carried out this case report without the dedicated involvement and valuable scientific contribution of Prof. William Carlos Nahas and Prof. Miguel Srougi (Urology), as well as of Prof. Pedro Puech-Leão and Prof. Nelson de Luccia (Vascular Surgery).

Funding

No source of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MPB is the principal investigator, along with RIL ang GCM. They wrote and revised the manuscript and were responsible for the care of the patient. GG, CBF and LCG revised the original draft, added references, and were major contributors to retrieving the images used. HAM, GBBL and GCM were involved as members of the vascular surgery team responsible for patient care, shared the patient’s timeline while in the emergency department and shared the intraoperative findings and images. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of University of São Paulo General Hospital approved the study, and the committee’s reference number is 68-20102020.

Consent for publication

Patient provided written consent to publish his case report, medical data, and radiology images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bigarella, M.P., Lopes, R.I., Gentile, G. et al. Bilateral external iliac artery pseudoaneurysms causing urinary obstruction and acute renal failure. CVIR Endovasc 5, 22 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-022-00302-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-022-00302-5