Abstract

Background

Ectopic meningiomas are rare neoplasms that occur entirely outside the intracranial and intraspinal cavities and account for only 1–2% of all meningiomas. These tumors have been reported at various sites, however they are predominantly observed in the head and neck region. Here, we detail a case of an adult diagnosed with ectopic meningioma of the neck.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old woman underwent evaluation for a neck swelling associated with difficult in swallowing. Clinical examination revealed a firm, non-tender and non-pulsatile swelling in the right side of neck. On imaging, a soft tissue mass lesion was seen involving the right supra-hyoid neck, centered at the right carotid space/retro-styloid parapharyngeal space. She underwent maximal safe resection of the tumor and a consensus was reached regarding the diagnosis of ectopic meningioma based on the histopathological, clinical and radiological findings. Relevant literature is reviewed.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of ectopic meningioma may pose difficulties due to their occurrence in uncommon sites. The primary approach to treatment entails the surgical removal of the neoplasm, and a multidisciplinary strategy is pivotal for achieving the best possible clinical outcomes for patients with this rare entity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Meningiomas are hypothesized to have arisen from the meningothelial cells of the arachnoid mater, and they are the most prevalent primary brain tumors in adults [1]. These tumors occur commonly as extra axial intracranial tumors, and less frequently as intradural–extramedullary spinal tumors [2]. On the contrary, extraneuraxial or ectopic meningiomas are very rare tumors, accounting for only 1–2% of all meningiomas [3].

Case presentation

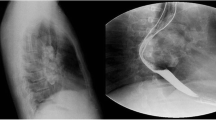

A 26-year-old woman with no comorbidities was evaluated for a swelling in the right side of the neck, which was progressively increasing in size over the past 4 years. Although initially asymptomatic, it was subsequently associated with pain and difficulty in swallowing, as well as recurrent episodes of sore throat. Local examination revealed a firm and non-tender swelling measuring 6 × 3 cm involving the right side of neck, extending inferiorly from the lower border of mandible. The swelling was found to be non- pulsatile, and there was no bruit detected on auscultation. On Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the neck, a well circumscribed lobulated heterogeneous soft tissue mass lesion measuring 6.8 × 6.5 × 3.9 cm (CC × AP × TR) was seen involving the right supra-hyoid neck. The lesion was centered at the right carotid space/retro-styloid parapharyngeal space, extending from the jugular fossa region cranially till the 4th cervical vertebral level caudally (just beyond carotid bifurcation), and it completely encased the cervical segment of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) and proximal half of the external carotid artery (ECA). It also displaced the parapharyngeal fat space anteriorly, parotid space and deep parotid lobe laterally, and right palatine tonsil/right pharyngeal wall anteromedially; however there was no significant airway luminal compromise. The mass lesion was isointense on T1‑weighted images, heterogeneously hyperintense with central hypointense areas on T2‑weighted images, and showed moderate to avid heterogeneous enhancement after the administration of contrast material (Fig. 1a–c).

Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the neck and skull base (without and with contrast) revealed an iso- to slightly hyperdense mass lesion with post contrast enhancement. Clumped calcific foci were seen in the cranial aspect of the lesion. No significant cervical lymphadenopathy was noted on either side. There was no intracranial extension (Fig. 1d, e). On CT Angiography (CTA), the ICA, common carotid artery (CCA) and vertebral artery (VA) showed normal origin, outline and caliber. The right ICA was displaced anteriorly and the right ECA was displaced anterolaterally by the lesion. The intracranial arteries showed normal outline and caliber (Fig. 1f). As biopsy from the mass lesion was suggestive of meningioma, a decision for surgical resection was taken. The tumor was operated upon via a mandibular split approach. Intraoperative examination showed a firm to hard lobulated mass in the right carotid space measuring approximately 6 × 5 cm. Cervical segment of the ICA was encased by the lesion; however the bulk of the tumor was behind the ICA. The cranial nerves- glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory and hypoglossal- were seen to be hypertrophied and embedded in the tumor. The patient underwent excision of the tumor, but a small residue was left behind at the region of the jugular foramen due to dense adhesions to the surrounding tissue. Postoperative MRI of the neck revealed a mild enhancing soft tissue mass measuring 2.3 × 2 × 2 cm (CC x AP x TR) encasing the cranial most aspect of the cervical ICA, suggestive of residual disease (Fig. 2).

The postoperative period was uneventful, and she was referred to our center for further evaluation and management. Neurological examination was within normal limits. Review of the histopathology slides revealed a neoplasm composed of meningothelial cells in whorls and lobules supported by a collagenous stroma. Plenty of psammoma bodies were noted. The tumor whorls were seen diffusely infiltrating adjacent adipose tissue, soft tissue, nerve bundles and ganglia; and also involved the coagulated resected margin. The proliferative index -Ki‑67 was 3–5%. On immunohistochemistry (IHC), the tumor cells were positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Based on these findings, we diagnosed ectopic Transitional Meningioma WHO Grade 1 of the neck (Fig. 3). In view of the grade 1 disease, it was decided to keep her on follow-up without any adjuvant treatment. Clinical evaluation and MRI scan of the neck were performed at 6-month intervals, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 36 months (Fig. 4).

a Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (in high-power microscopy) showing meningothelial whorls and a psammoma body; b Histopathology slide (in high power) showing low Ki-67 index; c Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (in high-power microscopy) showing meningioma whorls with perineural invasion; d Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (in low power microscopy) showing meningioma infiltrating adjacent fatty tissue and skeletal muscle; e Immunohistochemistry (in high-power microscopy) showing EMA staining

Discussion

Ectopic meningiomas, which are rare meningothelial neoplasms, differ from meningiomas with extracranial or extraspinal growth in that they occur entirely outside the intracranial and intraspinal cavities, without having any connection to the dura. Related acceptable terminologies for ectopic meningioma include extradural, extracranial/ extraspinal, extraneuraxial, heterotopic, cutaneous, calvarial or intraosseous meningioma. They can occur at various sites, however more than 90% of ectopic meningiomas present in the head and neck region. Other locations include orbit, skull, sinonasal tract, oropharynx, lung, mediastinum, middle ear, scalp and parotid gland [4].

These tumors may present with a diverse range of signs and symptoms, with the most common pattern being a slow-growing, painless mass [4]. In a study, the incidence of primary extradural meningioma (PEM) was 1.6% of all resected meningiomas, the male/female ratio was nearly 1:1; and a bimodal age distribution was observed, with a peak in the second decade of life and again from the fifth to seventh decades [5]

The histogenesis of ectopic meningioma is not well understood. The following four hypotheses have been proposed: (i) originating from the ectopic arachnoid cap cells; (ii) meningothelial cells traversing along the nerve sheaths exiting skull or vertebral column; (iii) originating from the pleuripotent mesenchymal cells that are capable of undergoing meningothelial differentiation or metaplasia; and (iv) meningothelial cells displaced or entrapped at the sites of traumatic skull fracture [4].

The neoplasms most frequently found in the carotid and parapharyngeal spaces of the neck include metastatic lymph node masses, lymphomas, minor salivary gland tumors, schwannomas, neurofibromas and paragangliomas [6]. Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is the most common imaging technique for evaluating a neck mass; however it might be difficult to arrive at the definitive diagnosis of meningioma based solely on radiological features. On MRI, the signal intensities of these neoplasms match those of their intracranial equivalents. Calcification is often present, either in a localized area of the lesion or dispersed throughout the tumor, and is best seen on CT images [7]. Due to the vascularity of these tumors and their propensity for intraoperative bleeding, CTA is occasionally done, mostly for surgical planning [8].

Ectopic menigiomas have similar macroscopic appearance and histopathological features to the central nervous system (CNS) meningiomas, with the exception of having more invasive properties [4]. In the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of CNS tumors, meningiomas are considered as a single tumor type with 15 subtypes, and three malignancy grades (CNS WHO grades 1–3) based on histopathology or subtype [1]. On immunohistochemistry (IHC), they express EMA and vimentin [1, 4]. The Somatostatin receptor (SSTR) 2A can be expressed in pulmonary meningothelial-like nodules [4]. The molecular basis of these neoplasms has not been extensively researched [4].

Complete surgical resection, if feasible, is the treatment of choice. However, achieving total resection may not be always possible due to the difficult anatomical locations and close proximity to vital structures [3, 5, 9]. Similar to other meningiomas, tumor grade and extend of resection are important prognostic factors for these tumors [4]. Distant metastases have been observed in approximately 6% of cases, typically in patients with malignant (WHO grade 3) lesions [4, 5]. A study that analyzed 231 cases of PEMs reported recurrence and tumor-related death rates of 22.4% and 8.2%, respectively, over a mean 3.03-year follow-up [3]. In a review by Lang et al., 168 PEMs were identified in 142 patients by a comprehensive literature search. The majority of the tumors (67%) had benign histology. Atypical and malignant meningiomas were associated with a statistically significant higher death rate compared to benign lesions (29% vs 4.8%, p < 0.004)[5]. Mattox et al. have recommended resection with wide margins for benign PEMs (WHO 1) and adjuvant therapy after resection for atypical (WHO 2) /malignant (WHO 3) PEMs [9].

In the present case, the final diagnosis was reached as a result of a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach. Considering the fact that she had a WHO grade 1 meningioma, the decision was to keep her on follow-up after surgical resection, and there were no clinical or radiological features of recurrence at 3 years.

Long-term follow-up is recommended with clinical assessments and imaging studies, as this would allow for prompt intervention in the event of recurrence [8].

Conclusions

Ectopic meningiomas are rare tumors that may present with unique hurdles in the diagnosis and treatment due to their occurrence at unusual sites. The primary treatment modality involves surgical resection of the tumor, with the aim of achieving complete excision whenever feasible. The contributions of a multidisciplinary team are important, and the final diagnosis is reached by correlating the histopathological features with the clinical and radiological findings. Continued research is necessary to further investigate the etiology, molecular and genetic characteristics, prognostic factors and optimal management of these tumors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AP:

-

Antero-posterior

- CC:

-

Cranio-caudal

- CCA:

-

Common carotid artery

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTA:

-

CT Angiography

- ECA:

-

External carotid artery

- EMA:

-

Epithelial membrane antigen

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- ICA:

-

Internal carotid artery

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PEM:

-

Primary extradural meningioma

- SSTR:

-

Somatostatin receptor

- TR:

-

Transverse

- VA:

-

Vertebral artery

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Louis DN, Meningioma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 5th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2021, pp. 283–298.

Devita VT, Rosenberg SA, Lawrence TS. Neoplasms of the Central Nervous System. In: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2018. (11th edn), pp. 1593–1595.

Liu Y, Wang H, Shao H, Wang C. Primary extradural meningiomas in head: a report of 19 cases and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(5):5624–32.

Antonescu CR, Perry A, Ectopic meningioma and meningothelial hamartoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft tissue and bone tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 3) https://publications.iarc.fr. pp 247–248.

Lang FF, Macdonald OK, Fuller GN, DeMonte F. Primary extradural meningiomas: a report on nine cases and review of the literature from the era of computerized tomography scanning. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(6):940–50. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.0940.

Bergeron RT. In re: Harnsberger HR, Osborn AG. Differential diagnosis of head and neck lesions based on their space of origin. 1. The suprahyoid part of the neck. AJR AM J Roentgenol 1991;157:147–154 and Smoker WRK, Harnsberger HR. Differential diagnosis of head and neck lesions based on their space of origin. 2. The infrahyoid portion of the neck. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;157:155–159. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(8):1628–9

Som PM, Curtin HD. Parapharyngeal space. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, (editors). Head and neck imaging, 3rd edn, St Louis, MO: Mosby, 1996

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Version 1.2023—March 24, 2023. Central Nervous System Cancers. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/nccn-guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1425. Accessed Date: 23 June 2023

Mattox A, Hughes B, Oleson J, Reardon D, McLendon R, Adamson C. Treatment recommendations for primary extradural meningiomas. Cancer. 2011;117(1):24–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25384.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BV was involved in the design and methodology, performed the literature search, collected the data and prepared the manuscript. AA was involved in the design and methodology, formal analysis and investigations, review and editing the manuscript. PB, AM, JV, NR and NJ were involved in the design methodology, formal analysis and investigations, writing original draft and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient included in this study.

Consent for publication

The patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vijayan, B., Arjunan, A., Balakrishnan, P. et al. Ectopic meningioma presenting as a neck mass: case report and review of literature. Egypt J Neurosurg 38, 47 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-023-00230-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-023-00230-z