Abstract

Background

Spinal epidermoid tumors are rare, comprising of less than 1% of tumors involving the spine. These tumors arise from pathological displacement of epidermal cells into the spinal canal. Therefore, these tumors can be congenital, when there is improper closure of the neural tube; or acquired, in patients who have had prior lumbar punctures, trauma, or surgery. Spinal epidermoids are typically found in the lumbosacral region but can be found in other locations as well.

Case presentation

We report an original case of a 50 year old. He presented with 1 year with back pain and bilateral sciatica. The patient was neurological intact with no sphincter incompetence. The magnetic resonance image of the lumbosacral spine showed a 12 × 3 cm well-circumscribed intradural mass at the L3–S1 level. The patient was operated on with posterior lumbar laminectomy for tumor removal. Postoperation, the patient had improved pain and numbness. The motor power was intact as preoperative.

Conclusions

MRI with DWI is especially useful to confirm the diagnosis with the lesions appearing hyperintense. The most conventional approach to resection involved laminectomies and intradural tumor resection. GTR provided better outcomes in most cases even when the tumor was adherent to the nearby spinal cord or nerve roots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spinal epidermoid tumors are infrequent, comprising of less than 1% of tumors found in the spine [1]. These tumors originate from pathological implanting of epidermal cells into the spinal canal. Consequently, these tumors can be congenital, when there is inappropriate closure of the neural tube; or acquired, in patients who have had former lumbar punctures, trauma, or surgery [2, 3]. Spinal epidermoids are mainly found in the lumbosacral region but could be found in other sites as well [4]. They look, intraoperatively, as white masses that are encapsulated and are commonly described to as “pearly tumors” [5]. Patients generally present with pain as well as neurological disorders that may include: muscle weakness and atrophy, sensory disturbances, and loss of sphincter control [3, 5].

Methods of case report

We report an original case of a 50 year old. He presented with 1 year with back pain and bilateral sciatica. The patient was neurological intact with no sphincter incompetence.

He denied any history of trauma, lumbar puncture, or previous surgery related to the spine. Past medical history showed no drug use. No family history has been observed. No muscle atrophy, no evidence of spinal dysraphism has been observed.

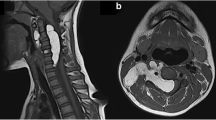

The magnetic resonance image of the lumbosacral spine showed a 12 × 3 cm well-circumscribed intradural mass at the L3–S1 level, which was isointense on T1 (Fig. 1), hypointense on T2 (Fig. 2) with no contrast enhancement (Fig. 3). The findings were with possible a s diagnosis schwannoma or meningioma, and the diagnosis of intradural epidermoid cyst at the cauda equina level was suspected intraoperatively as we found pearly soft and friable mass.

The patient was operated on with posterior lumbar laminectomy for tumor removal. We utilized intra-operation imaging with mobile C-arm to identify skin incision and the accurate level of the tumor. We completed a laminectomy and after that, a durotomy at the level of L3–S1 was done. The lesion capsule was well defined and closely connected to surrounding nerve roots and vessels of the cauda equina region. Its content was pearly, soft, and friable. The cyst with its capsule was meticulously dissected and totally removed under the microscope. The nearby nerve roots and vessels were preserved (Fig. 4).

a: Postoperative T1. The 2-month postoperative imaging demonstrated a complete resection of the tumor. b: Postoperative T2. The 2-month postoperative imaging demonstrated a complete resection of the tumor. c: Postoperative T1 contrast. The 2-month postoperative imaging demonstrated a complete resection of the tumor

Macroscopically: a well-circumscribed and unilocular soft cyst with friable contents was observed.

The histopathology: The sections examined revealed strips of cyst wall lined by stratified squamous epithelium with orthokeratotic keratin and an intact granular layer, but devoid of rete. Also seen abundant fragments of laminated loose keratin (Fig. 5). Diagnosis of the lumbar mass features was consistent with intraspinal epidermoid cyst with no malignancy.

Postoperation, the patient had improved pain and numbness. The motor power was intact as preoperative and treated with antibiotics and physiotherapy for postoperative back pain of the wound and back muscles. The patient was able to walk steadily; he also denied any numbness or tingling in his lower extremities. The 2-month postoperative imaging demonstrated a complete resection of the tumor on MRI images (Fig. 4).

Discussion

A total of 66 cases (including the present case) were revised literature in multiple centers and studies [1, 6] total number of 30 male patients and 36 female patients. The median age was 23 years (range, 0–71 years). The most frequent symptoms were back and leg pain. Thirty cases were acquired from either the lumbar puncture or prior surgery, 9 cases were considered congenital, and 27 cases were idiopathic. Most frequent treatment was surgical, specifically, laminectomies and intradural tumor surgical removal. A total of 44 patients had GTRs, 16 had subtotal resections (STRs), and in 8 patients the type of resection could not be defined. Two patients have developed recurrence of their tumors after surgery. One patient had a GTR first and later developed a recurrence, which was then partially resected at a later surgery. Different patient had a STR and then developed a recurrence, which was then partially surgically removed again. Twenty-six patients (40%) had tumors that were considered as adherent, 10 patients (15%) had tumors that had not been adherent, and for the remaining cases tumor adherence could not be identified. The median follow-up time was 4.2 months among all of the reviewed studies.

Intradural spinal epidermoid tumors or cysts are infrequent, benign lesions that can arise when epidermal cells are unnaturally dislodged into the thecal sac. During embryogenesis, the central nervous system and skin both evolve from ectoderm, which is why epidermal cells may grow within the thecal sac. These tumors can either be congenital or acquired. Congenital causes of spinal epidermoid tumors involve spina bifida, myelomeningocele, diastematomyelia, hemivertebrae, and syringomyelia. Acquired causes consist of: lumbar puncture, trauma, and prior surgery [3]. Lumbar puncture is a well-known iatrogenic cause of epidermoid formation, but can theoretically be avoided by the use of styletted needles. However, in the pediatric population the stylet may be removed and consequently carries the chance of implanting epidermal cells in the dural sac.1 Historically, the bore of the needle was larger than those currently in use and that is why it could displace a greater number of epidermal cells [6].

Symptoms are partly dependent on the location of the tumor but may include weakness, sensory disturbances, low back pain, painful radiculopathy, and bowel and bladder dysfunction. In the case of rupture of the epidermoid tumor’s capsule into the subarachnoid space, patients may present with acute, chemical meningitis [7]. Manno et al. [8] found that most of spinal epidermoid tumors formed in the lumbar spine (92%). Another study examined the growth rate of epidermoid tumors and discovered that they grow at a similar rate as normal skin cells do, which explains why it is a delayed presentation [9].

Since cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) appears hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2, multiple studies have been suggested using diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) as the most conclusive MRI sequence to diagnose and monitor spinal epidermoid tumors [10, 11]. On DWI, spinal epidermoid tumors appear hyperintense, which helps distinguish it from CSF, which is hypointense [10]. The differential diagnosis of these intradural, extramedullary tumors includes dermoid, meningioma, lipoma, and neurofibroma [6].

Pathological examination of epidermoid tumors shows stratified squamous epithelium with an outer layer of collagenous tissue. The interior of the tumor is rich with cholesterol crystals that form through desquamation of keratin from the epithelial lining. Epidermoid tumors can be distinguished from dermoid tumors by looking for adnexal structures [3, 5].

In symptomatic patients, the surgical removal is the primary treatment. Because of that these tumors can be tightly attached to the surrounding neural tissue, particular care should be taken when dissecting to create a plane with the nerve roots or spinal cord. When possible, total excision of the tumor should be achieved since recurrence or chemical meningitis may occur if residual tumor is left behind. However, if the capsule is adherent to the nerve roots, a STR may be suitable to reduce mass effect. Patients should follow up periodically monitor for recurrence even if total resection was accomplished [3]. In patients who have undergone multiple surgeries without complete resolution of symptoms or in those with extensive fibrosis, radiotherapy may be suitable for palliation [5, 12]. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring is often applied when resecting spinal tumors. Given that epidermoid tumors may be tightly adherent to the nearby neural tissue, EMG and somatosensory-evoked potentials can be used to help guide the surgical resection of these tumors [13]. Spinal epidermoid tumors tend to present at an early age with a median age of diagnosis being [14]. This is mainly because that congenital deformities involving closure of the neural tube can lead to the unusual displacement of epithelial cells within the dura. Additionally, performing lumbar punctures without the use of a stylet in the pediatric population has further increased the incidence of these tumors in younger patients [1]. The literature reviews produced a total of 27 epidermoids that were described as adherent. Of these, 20 patients experienced a GTR with 18 had preserved motor power after surgery. STR was performed 5 out of 27 adherent tumors with only 2 of these patients feeling a preserved motor power. This suggests that even in the case of adherent tumors, GTR provides better outcomes despite its expected risk of neurological deficits when dissecting away from the neural elements.

Conclusions

Spinal epidermoid tumors are uncommon, benign tumors. As seen in other intradural, extramedullary tumors, patients typically appear with low back and leg pain, bladder and bowel dysfunction, muscle atrophy, and sensory disturbances. Many cases are acquired from trauma, surgery, or lumbar puncture (46%). MRI with DWI is especially useful to confirm the diagnosis with the lesions appearing hyperintense. The most conventional approach to resection involved laminectomies and intradural tumor resection. GTR provided better outcomes in the majority of cases even when the tumor was adherent to the nearby spinal cord or nerve roots.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted image

- GTR:

-

Gross total resection

- STR:

-

Subtotal resection

References

Per H, Kumandaş S, Gümüs H, Yikilmaz A, Kurtsoy A. Iatrogenic epidermoid tumor: late complication of lumbar puncture. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(3):332–6.

Park JC, Chung CK, Kim HJ. Iatrogenic spinal epidermoid tumor. A complication of spinal puncture in an adult. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2003;105(4):281–5.

Morita M, Miyauchi A, Okuda S, Oda T, Aono H, Iwasaki M. Intraspinal epidermoid tumor of the cauda equina region: seven cases and a review of the literature. Clinical Spine Surgery. 2012;25(5):292–8.

Teksam M, Casey S, Michel E, Benson M, Truwit C. Intraspinal epidermoid cyst: diffusion-weighted MRI. Neuroradiology. 2001;43(7):572–4.

Yin H, Zhang D, Wu Z, Zhou W, Xiao J. Surgery and outcomes of six patients with intradural epidermoid cysts in the lumbar spine. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12(1):1–7.

Ziv ET, McComb JG, Krieger MD, Skaggs DL. Iatrogenic intraspinal epidermoid tumor: two cases and a review of the literature. Spine. 2004;29(1):E15–8.

Dobre MC, Smoker WR, Moritani T, Kirby P. Spontaneously ruptured intraspinal epidermoid cyst causing chemical meningitis. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(4):587–9.

Manno NJ, Uihlein A, Kernohan JW. Intraspinal epidermoids. J Neurosurg. 1962;19(9):754–65.

Alvord EC Jr. Growth rates of epidermoid tumors. Annals Neurol Off J Am Neurol Assoc Child Neurol Soc. 1977;2(5):367–70.

Manzo G, De Gennaro A, Cozzolino A, Martinelli E, Manto A. DWI findings in a iatrogenic lumbar epidermoid cyst: a case report. Neuroradiol J. 2013;26(4):469–75.

Thurnher MM. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DWI) in two intradural spinal epidermoid cysts. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(11):1235.

Bretz A, Van den Berge D, Storme G. Intraspinal epidermoid cyst successfully treated with radiotherapy: case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(6):1429–32.

Liu H, Zhang J-N, Zhu T. Microsurgical treatment of spinal epidermoid and dermoid cysts in the lumbosacral region. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(5):712–7.

Phillips J, Chiu L. Magnetic resonance imaging of intraspinal epidermoid cyst: a case report. J Comput Tomography. 1987;11(2):181–3.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable

Funding

No funding was taken.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HE helped in the idea of the research and collecting material. MS collected material and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval from Menoufia Faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee under reference number 12-2021 NEUS and detailed consent to participate were taken from the patient.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was taken from the patient.

Competing interests

There were no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elnoamany, H., Salim, M. Idiopathic lumbar epidermoid: review of literature and case report. Egypt J Neurosurg 38, 15 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-023-00188-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-023-00188-y