Abstract

Background

Potato tuber worm (PTM) [Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae)] is one of the most significant and widespread pests of potato. PTM damages potatoes both in the field and in potato storage areas. Control of the pest is getting harder as it is developing resistance to pesticides. Several entomopathogenic nematode (EPN) species have been reported to successfully control numerous agricultural pests worldwide. The main aim of the study was to isolate native nematode/s as a biological control agent against P. operculella. Morphometric measurements of the infective juvenile (IJ) and sequencing and characterization of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region was used to identify the nematode isolate to species level. The efficacy of EPN isolate Z-1 obtained from Zonguldak province, Turkey was tested against different life stages of the pest. Experiments were conducted in 150 ml plastic pots containing sterile soil mixture. Four EPN concentrations (i.e., 0, 250, 500 and 1000 IJs/ml) were applied to the soil. Data relating to the mortality of different life stages were collected daily till 6 days after inoculation.

Results

Molecular analyses based on the ITS sequence and morphometric data revealed that isolate Z-1 was Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. Mortality rates of PTM larvae exposed to 250, 500, and 1000 IJs/ml concentrations of native EPN were 62.9 ± 9.8, 74.0 ± 3.7, and 92.5 ± 3.7%, respectively. There were non-significant differences among tested EPN concentrations for pupal mortality and the highest concentration (i.e., 1000 IJs/ml) caused 25.6% mortality.

Conclusions

The results revealed that the native H. bacteriophora isolate was effective against late-stage larvae of PTM under laboratory conditions. Therefore, it can be used as an alternative management option of the pest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is one of the most important vegetables extensively consumed in human nutrition. Potato tuber moth (PTM) [Phthorimaea operculella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae)] is an important and widespread pest of potato (Keasar and Sadeh 2007). This pest is commonly observed in tropical and subtropical regions of the world where potato is extensively produced (Malakar and Tingey 2006). It has been reported from several countries including Turkey (Kroschel et al. 2013). PTM negatively affects the crop in the field as well as in storage. The larvae can complete their development on leaves and in the tubers. The larvae develop in the tubers until their last instar emerge from the tuber and pupate in the soil. The damage caused by the pest reduces tuber quality and increases the risk of pathogen entry into the tubers (Rondon 2010).

Use of insecticides is the most popular control method for this pest in the field and warehouses (Dillard et al. 1993). However, intensive use of pesticides has resulted in the development of resistance, rendering insecticides used to be ineffective (Hafez 2011). Also, the negative effects of insecticides on non-target organisms have led to an increased interest in the development of alternative control methods (Henderson and Horne 1996). Entomopathogenic nematode (EPN) species, are obligate insect killers inhabiting soil, have been used as alternative control methods against various harmful insects in the world (Hazir et al. 2003). EPNs kill their hosts within 24–48 h of their application. The use of an EPN for the management of a certain pest insect depends on a number of variables, including the nematode’s host range, host seeking or foraging technique, tolerance of environmental conditions, and their survival and performance under different abiotic conditions (temperature, moisture, soil type, exposure to UV radiation, soil salinity and organic content, application methods, agrochemicals, and other factors). The four most important variables are moisture, temperature, susceptibility of the targeted insect, and foraging technique of the nematode (Grewal et al. 2005). Few studies have been conducted on the management of PTM with EPNs (Yağcı et al. 2021). However, no study has been conducted in Turkey to manage the pest through EPNs. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the efficiency of a local EPN, i.e., H. bacteriophora (isolate Z-1) Poinar (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) against different stages of the PTM under controlled conditions. The results would provide valuable insights for the management of potato tuber moth by native EPN.

Methods

Rearing of Phthorimaea operculella larvae and pupae

Phthorimaea operculella culture was obtained from infested potatoes available at Entomology laboratory, Central Plant Protection Research Institute, Ankara, Turkey. Infested tubers were placed in cylindrical pots (15 cm diameter and 30 cm height) and cultured under 25 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% RH and 14:10 light: dark conditions. The pots were covered with mesh lids to prevent the escape of adults. The filter paper was placed on the mesh for egg laying. The filter papers were controlled at of 4–6 h intervals to obtain eggs of the same age. The eggs laid on the lowest surface of the filter paper were used in the experiments. Similarly, larvae emerging on the same day from hatched eggs were used in the experiments. All larval stages were monitored daily and mature larvae and individuals entering the pupal stage were used in the assays. In addition, a long cotton wick soaked with 10% (w/v) honey solution was placed in a cage to feed the adults (Golizadeh et al. 2014).

Source of nematode

The nematode (isolate Z-1) used in this study was isolated from a soil sample taken from the clover field in Zonguldak province, Turkey. Soil sample was processed for nematode extraction using the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella L. (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) baiting technique (Bedding and Akhurst 1975) and White trap (White 1927). Pathogenicity of the isolated nematode was confirmed by re-infecting healthy G. mellonella larvae and newly emerged infective juvenile nematodes (IJs), collected from White trap, were kept at 10 °C for further study (Hazir et al. 2022).

Molecular identification of nematode isolate

DNA was extracted from single hermaphrodite as described by Cimen et al. (2016). Briefly, Eppendorf tubes with the nematode and 20 µl of extraction buffer (17.7 µl of ddH2O, 2 µl of 10 X PCR buffer, 0.2 µl of 1% tween, and 0.1 µl of proteinase K) was frozen at − 20 °C for 20 min and then immediately incubated at 65 °C for 1 h, followed by 10 min at 95 °C. The lysates were cooled on ice, then centrifuged and 2 µl of supernatant was used for PCR. ITS regions (ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2) were amplified using primers 94: TTGAACCGGGTAAAAGTCG (F), and 93: TTAGTTTCTTTTCCTCCGCT (R) in PCR master mix with ddH2O 7.25 μl, 10 × PCR buffer 1.25 μl, dNTPs 1 μl, 0.75 μl of each forward and reverse primer, polymerase 0.1 μl and 1 μl of DNA extract. The PCR profiles were used as follows for ITS: 1 cycle of 94 °C for 7 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 60 s, 45 °C for 60 s, 72 °C for 60 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min (Vrain et al. 1992). PCR product was examined by electrophoresis (45 min, 120 V) in a 1% TAE buffered agarose gel. The PCR product was sent to a company for sequencing (Medsantek, Turkey). DNA results were deposited in GenBank under accession number OQ130749. The sequence was edited and blasted in GenBank of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). An alignment of our sample together with sequences of related heterorhabditid species were produced for ITS region using default ClustalW parameters in MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013) and optimized manually in BioEdit (Hall 1999).

The phylogenetic tree of the ITS gene was obtained by the minimum evolution method (Rzhetsky and Nei 1992) in MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013). Caenorhabditis elegans was used as out-group taxon. The minimum evolution tree was searched using the close-neighbor-interchange (CNI) algorithm (Nei and Kumar 2000). The neighbor- joining algorithm (Saitou and Nei 1987) was used to generate the initial tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method (Nei and Kumar 2000) and were expressed as the number of base differences per site.

Morphological identification of nematode isolate

Infective juveniles’ stage of nematode was used for morphological identification. IJs were collected approximately one week after emergence from the cadavers, heat-killed in Ringer’s solution and fixed in Triethanol- amine formalin (Courtney et al. 1955). The nematode samples were subsequently processed in anhydrous glycerin for mounting (Seinhorst 1959). Morphometric analysis of the nematode specimens was done for 20 individuals of IJ, using light microscopy and the image analyzing software Cell D (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions). Morphological observations were made following the taxonomic criteria suggested by Stock and Kaya (1996).

Rearing wax moth (Galleria mellonella) larvae

Wax moth larvae were reared in one L bottle with a special diet containing flour (890 g), milk powder (445 g), dry baker’s yeast (222 g), honey (500 g), glycerin (500 g), and beeswax (125 g). Beeswax, honey, and glycerin were melted and added to other mixture (flour, bran, milk powder and yeast) (Mohamed and Coppel 1983). Wax moth eggs were placed on the food medium in one liter glass jars and kept in an incubator maintained at 16/8 h light: dark period, and 23–24 °C for 40–45 days. Sixth instar larvae of wax moth were used for the mass rearing of EPNs.

Rearing of entomopathogenic nematodes

Wax moth larvae were used for mass rearing of EPN isolate used in the experiment. Ten larvae were released in a Petri dish (6-cm diameter), having Whatman 1 paper soaked with distilled water. A suspension of IJs was applied on wax moth larvae. The Petri dishes were wrapped with parafilm and placed in the incubator at 20–23 °C. Larval mortality was controlled every day. The EPN IJs were obtained from infected wax moth larvae using “White trap” method (White 1927) transferred into culture flasks and kept in a refrigerator at 10 °C. To keep the nematodes active, the same process was repeated every one to two months using fresh wax moth larvae as hosts. In this way the cultures were renewed at the Nematology Laboratory, Directorate of Plant Protection Central Research Institute, Ankara, Turkey.

Experiments

The experiments were conducted in 150 ml plastic pots containing a mixture of soil (80% sand, 15% soil and 5% clay) sterilized at 121 °C (Chen et al.1995). The assay pots were placed in an incubator at 25 °C under complete dark. One last instar larva and a pupa were released in each pot. The native EPN concentrations (i.e., 0, 250, 500 and 1000 IJs) were applied directly to the larva by pipette onto soil (Kakhki et al. 2013). Only water was applied to the larvae and pupae in the control pots. Larval mortality was calculated daily for seven days after the application of EPN concentrations. Laboratory studies had ten replications for each EPN concentration. The experiment was repeated three times under the same conditions on different dates. Dead larvae were placed on a white trap and EPN larvae were obtained from infected potato tuber moth larvae. Insect cadavers were examined in distilled water under a stereomicroscope.

Data analysis

Obtained data were converted to percent and corrected mortality were calculated after adjusting for the mortality in the control using Abbott’s formula (Abbott 1925). The mortality data had non-normal distribution; therefore, these were transformed by using arcsine transformation technique to meet the normality assumption of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Finally, the mortality data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Duncan’s multiple range post-hoc test was used to compare concentrations’ means where ANOVA denoted significant differences. The data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 23.0.

Results

Molecular identification of nematode isolate

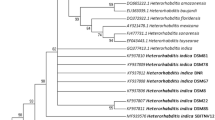

Molecular analyses based on the ITS sequence revealed that isolate Z-1 was Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. It exhibited 99.69% ITS sequence similarity with H. bacteriophora MK072810 and 99.38% similarity with H. bacteriophora EF043438. The analysis of all available sequences of known Heterorhabditis species from GenBank with those generated during the survey, based on minimum evolution method, are indicated in Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of the species used in the study and other related species of Heterorhabditis based on analysis of ITS rDNA regions. Caenorhabditis elegans was used as outgroup taxon. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (10,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Branch lengths indicate evolutionary distances and are expressed in the units of number of base differences per site

Morphological identification of nematode isolate

The morphometric characters of the IJ of isolate Z-1 were compared to the original description of H. bacteriophora by Poinar (1990). All measured morphometric characters were found to be very similar to original description of H. bacteriophora (Table 1).

Pathogenicity tests

Different EPN concentrations caused varying mortality against last instar larvae of the PTM. The mortality was increased by increasing IJs concentration and time after the application of different EPN concentrations. The mortality caused by 250, 500 and 1000 IJs concentrations was 6.6, 23.3, and 50.0%, respectively at 24 h after application. The EPN concentrations significantly (F = 14.92, P = 0.00) differed from each other after 24 h. The mortality by 250, 500 and 1000 IJs concentrations increased to 30.0%, 53.3%, and 66.6%, respectively, at 48 h with a significant difference (F = 8.26, P = 0.02) among the concentrations. Similarly, the mortality caused by 250, 500 and 1000 IJs concentrations was 35.6, 60.7, and 82.1%, respectively at 72 h with a significant effect (F = 14.24, P = 0.00). Likewise, the mortality was 49.9, 64.2, and 82.1% under 250, 500 and 1000 IJs concentrations, respectively at 96 h and concentrations significantly (F = 6.83, P = 0.03) differed from each other. Similar effects were observed at 120 and 144 h. The mortality was 53.5, 64.2, and 82.1% under 250, 500 and 1000 IJs concentrations, respectively at 120 h and concentrations had a non-significant (F = 4.41, P = 0.07) effect. The mortality was 62.9, 74.0, and 92.5%, under 250, 500 and 1000 IJs concentrations, respectively at 144 h and concentrations had a significant (F = 5.70, P = 0.04) effect (Table 2).

The efficacy of EPN concentrations against PTM larvae increased with increasing time. The 250 IJs concentration caused 6.6, 30.0, 35.6, 49.9, 53.5, and 62.9% mortality at 24, 48, 72, 96, 120 and 144 h after application. Similarly, 500 IJs concentration caused 23.3, 53.3, 60.7, 64.2, 64.2 and 74.0% mortality of last instar larvae at 24, 48, 72, 96, 120 and 144 h after application, respectively. The mortality at 24–48 and 72–96 h was statistically similar (F: 24.47; P = 0.00). The highest concentration (1000 IJs) caused 50.0, 66.6, 82.1, 82.1, and 92.5% mortality at 24, 48, 72, 96, 120 and 144 h after application, respectively, and the effects at 72–96–120 h were in the same group (F: 5.3424; P = 0.01).

No mortality was recorded in control treatment in the first 48 h. The mortality was 6.6% at 72–96-120 h which reached to 10.0% at 144 h after the initiation of experiment. The 250, 500, and 1000 IJs concentrations of native EPN caused 17.2, 25.0 and 25.6% pupal mortality, respectively at 240 h. There was non-significant difference (F: 0.18, P = 0.84) between the tested concentrations for pupa mortality.

Discussion

This study indicated that last instar larvae of the PTB were highly susceptible to native EPN H. bacteriophora (isolate Z-1). The highest EPN concentration (1000 IJs/ml) caused 92.5% mortality of last instar larvae and 25.6% mortality of pupae at 25 °C. Larvae and pupae mortality increased with increasing concentration of EPN. The highest pupae and larvae mortality were recorded by the highest EPN concentration (1000 IJs/ml) included in the present study. The EPN species was ineffective against the pupal stage, but that there are a host of strain-dependent non-lethal effects during and after the transition to adulthood including altered developmental times (Filgueiras and Willett 2021).

The susceptibility of PTM against EPN infection depended on various factors such as the growth stage of insect host. The stage of insect growth has an important role on vulnerability to EPN infection (Kaya and Hara 1980). Last stage larvae (prepupae) were the most susceptible stage, showing the highest mortality at all EPNs concentrations. Several studies have investigated the efficacy of EPNs against the PTM. Yan et al. (2020) tested different concentrations of Steinernema carpocapsae against 2nd, 3rd, and 4th larval instars of PTM under controlled conditions. They reported that the fourth instar larvae were the most susceptible. Kakhki et al. (2013) showed that L4 larval mortality of PTM was significantly influenced by nematode strain and applied concentrations of infective juveniles. Yağcı et al. (2021) indicated that H. bacteriophora (TOK-20) isolate was the most effective at 1000 IJs/ml concentration against last instar larvae of PTM. Moawad et al. (2018) found that S. carpocapsae and H. bacteriophora caused 98–100% mortality in PTM larvae. Mhatre et al. (2020) reported that Steinernema cholashanense caused the highest mortality in 4th instar larvae (100%) compared to the pupae (30%).

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicated that H. bacteriophora (isolate Z-1) had a good potential for the control of PTM larvae. It provided an advantage in terms of applicability of EPN, as it effective on the larvae and pupae in the soil. However, future studies are necessary to determine the efficacy of EPN against PTM under field conditions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EPNs:

-

Entomopathogenic nematodes

- IJs:

-

Infective juveniles

- PTM:

-

Potato tuber moth

- P. operculella :

-

Phthorimaea operculella

- H. bacteriophora :

-

Heterorhabditis bacteriophora

- G. mellonella :

-

Galleria mellonella

References

Abbott WS (1925) A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol 18:265–267

Andalo V, Nguyen KB, Moino A (2006) Heterorhabditis amazonensis n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Amazonas, Brazil. Nematology 8:853–867

Bedding RA, Akhurst JR (1975) A simple technique for the detection of insect parasitic rhabditid nematodes in soil. Nematologica 21:10–11

Chen SY, Dickson DW, Mitchell DJ (1995) Effects of soil treatments on the survival of soil microorganisms. J Nematol 27(4S):661–663

Cimen H, Půža V, Nermut J, Hatting J, Ramakuwela T, Hazir S (2016) Steinernema biddulphi n. sp., a new entomopathogenic nematode (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from South Africa. J Nematol 48(3):148–158. https://doi.org/10.21307/jofnem-2017-022

Courtney WD, Polley D, Miller VI (1955) TAF, an improved fixative in nematode technique. Plant Dis Report 39:570–571

Dillard HR, Wicks TJ, Philip B (1993) A grower survey of diseases, invertebrate pests, and pesticide use on potatoes grown in South Australia. Aust J Exp Agric 33:653–661. https://doi.org/10.1071/EA9930653

Filgueiras C, Willett DS (2021) Non-lethal effects of entomopathogenic nematode infection. Sci Rep 11:17090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96270-2

Golizadeh A, Esmaeili N, Razmjou J, Rafiee-Dastjerdi H (2014) Comparative life tables of the potato tuberworm, Phthorimaea operculella, on leaves and tubers of different potato cultivars. J Insect Sci 14(42):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.014.42

Grewal PS, Ehlers RU, Shapiro-Ilan DI (2005) Nematodes as biological control agents. CABI Publishing, Wallingford

Hafez E (2011) Insecticide resistance in potato tuber moth Phthorimaea operculella Zeller in Egypt. J Am Sci 7(10):263–266

Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98

Hazir S, Kaya HK, Stock SP, Keskin N (2003) Entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) for biological control of soil pests. Turk J Biol 27:181–202

Hazir S, Kaya H, Touray M, Cimen H, Shapiro-Ilan DS (2022) Basic laboratory and field manual for conducting research with the entomopathogenic nematodes, Steinernema and Heterorhabditis, and their bacterial symbionts. Turk J Zool 46(4):305–350. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-0179.3085

Henderson AP, Horne PA (1996) Adoption of integrated pest management for potato moth control: attitudes and awareness in Victoria. HRDC Report, Institute for Horticultural Development Victoria

Kakhki MH, Karimi J, Hosseini M (2013) Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes against potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) under laboratory conditions. Biocontrol Sci Tech 23(2):146–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2012.745481

Kaya HK, Hara AH (1980) Differential susceptibility of Lepidopterous pupae to infection by the nematode Neoaplectana carpocapsae. J Invertebr Pathol 36:389393

Keasar T, Sadeh A (2007) The parasitoid Copidosoma koehleri provides limited control of the potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella, in stored potatoes. Biol Control 42:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.03.012

Kroschel J, Sporleder M, Tonnang HEZ, Juarez H, Carhuapoma P, Gonzales JC, Simon R (2013) Predicting climate-change-caused changes in global temperature on potato tuber moth Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller) distribution and abundance using phenology modeling and GIS mapping. Agric for Meteorol 170:228–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.06.017

Li XY, Liu QZ, Nermut J, Půža V, Mráček Z (2012) Heterorhabditis beicherriana n. sp. (Nematoda: Heterorhabditidae), a new entomopathogenic nematode from the Shunyi district of Beijing, China. Zootaxa 3569:25–40

Malakar R, Tingey WM (2006) Aspects of tuber resistance in hybrid potatoes to potato tuber worm. Entomol Exp Appl 120:131–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00435.x

Mhatre PH, Patil J, Rangasamy V, Divya KL, Tadigiri S, Chawla G, Bairwa A, Venkatasalam EP (2020) Biocontrol potential of Steinernema cholashanense (Nguyen) on larval and pupal stages of potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller). J Helminthol 94:e188. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X20000723

Moawad SS, Salah MME, Metwally HM, Ebadah IM, Mahmoud YA (2018) Protective and curative treatments of entomopathogenic nematodes against the potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Zell.). Biosci Res 15(3):2602–2610

Mohamed MA, Coppel HC (1983) Mass rearing of the greater wax moth Galleria melonella (Lepidoptera: Galleridae) for small-scale laboratory. Great Lakes Entomol 16(4):139–141

Nei M, Kumar S (2000) Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York, p 333

Nguyen KB, Shapiro-Ilan DI, Stuart, RJ, Mccoy CW, James RR, Adams BJ (2004) Heterorhabditis mexicana n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Tamaulipas, Mexico, and morphological studies of the bursa of Heterorhabditis spp. Nematology 6:231–244

Nguyen KB, Gozel U, Koppenhöfer HS, Adams BJ (2006) Heterorhabditis floridensis n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Florida. Zootaxa 177:1–19

Nguyen KB, Shapiro-Ilan DI, Mbata GN (2008) Heterorhabditis georgiana n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Georgia, USA. Nematology 10:433–448

Phan LK, Subbotin SA, Nguyen CN, Moens M (2003) Heterorhabditis baujardi sp. n. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Vietnam with morphometric data for H. indica populations. Nematology 5:367–382

Poinar GO (1990) Biology and taxonomy of Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae. In: Gaugler R, Kaya HK (eds) Entomopathogenic nematodes in biological control. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 23–61

Poinar GO, Karunakar GK, David H (1992) Heterorhabditis indicus n. sp. (Rhabditida, Nematoda) from India: separation of Heterorhabditis spp. by infective juveniles. Fundam Appl Nematol 15:467–472

Rondon SI (2010) The potato tuberworm: a literature review of its biology, ecology, and control. Am J Potato Res 87:149–166

Rzhetsky A, Nei M (1992) A simple method for estimating and testing minimum evolution trees. Mol Biol Evol 9:945–967

Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425

Seinhorst JW (1959) A rapid method for the transfer of nematodes from fixative to anhydrous glycerin. Nematologica 4:117–128

Stock SP, Kaya HK (1996) A multivariate analysis of morphometric characters of Heterorhabditis species (Nematoda: Heterorhabditidae) and the role of morphometrics in the taxonomy of species of the genus. J Parasitol 82:806–813

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729

Vrain TC, Wakarchuk DA, Levesque AC, Hamilton RI (1992) Intraspecific rDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism in the Xiphinema americanum group. Fundam Appl Nematol 15:563–573

White GF (1927) A method for obtaining infective nematode larvae from culture. Science 66:302–303

Yağcı M, Yücel C, Erdoğuş FD, Akbulut FM (2021) Efficiency of entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) on the potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller)) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) under controlled conditions. J Aegean Agric Res Inst (ETAE) 31(2):170–174

Yan JJ, Sarkar SC, Meng RX, Stuart R, Gao YL (2020) Potential of Steinernema carpocapsae (Weiser) as a biological control agent against potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). J Integr Agric 19(2):389–393

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our thanks to Republıc of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture And Forestry General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies.

Funding

This study is funded by Republıc of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture And Forestry General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies. This funder provided all chemicals and materials used in experimental bioassay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB and MY participated in setting the work planning and executing the experimental work. CY analyzed the all data (statistical analyses) in study. AB rearing Phthorimaea operculella larvae and pupae for study. MY mass rearing entomopathogenic nematodes and participated in experimental studies. HÇ detected species of local EPN isolates. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barış, A., Yağcı, M., Çimen, H. et al. Efficacy of a native entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (isolate Z-1) against potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Turkey. Egypt J Biol Pest Control 33, 35 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-023-00680-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-023-00680-5