Abstract

The efficacy of the native entomopathogenic fungus, Isaria fumosorosea TR-78-3, was evaluated against females of the bark and ambrosia beetles, Anisandrus dispar Fabricius and Xylosandrus germanus Blandford (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), under laboratory conditions by two different methods as direct and indirect treatments. In the first method, conidial suspensions (1 × 106 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1) of the fungus were directly applied to the beetles in Petri dishes (2 ml per dish), using a Potter spray tower. In the second method, the same conidial suspensions were applied on a sterile hazelnut branch placed in the Petri dishes. The LT50 and LT90 values of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 were 4.78 and 5.94/days, for A. dispar in the direct application method, while they were 4.76 and 6.49/days in the branch application method. Similarly, LT50 and LT90 values of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 for X. germanus were 4.18 and 5.62/days, and 5.11 and 7.89/days, for the direct and branch application methods, respectively. The efficiency of 1 × 106 conidia ml−1 was lower than that of 1 × 108 against the beetles in both application methods. This study indicates that I. fumosorosea TR-78-3 had a significant potential as a biological control agent against A. dispar and X. germanus. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the efficacy of the isolate on the pests under field conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), having approximately 3400 species in the sub-families Scolytinae and Platypodinae, are among the major pests which threat many fruit and forest trees (Hulcr and Dunn 2011). These beetles make galleries through sapwood (xylem) of host trees and cultivate symbiotic fungi such as Ambrosiella spp. and Raffaelea spp. in the galleries for their food (Harrington 2005). The symbiotic fungi which have co-evolved with ambrosia beetles provide nutrition required for the development of larvae and adults (Norris 1979). The fungi are carried by females in a specialized structure known as mycangium or mycangia (Six 2003). Moreover, ambrosia beetles often inoculate secondary pathogenic fungi such as Fusarium spp. (Kessler 1974) or bacteria (Hall et al. 1982) during entry into trees (Oliver and Mannion 2001). Consequently, these beetles could harm the trees by carrying plant diseases, tunneling the trees, and farming symbiotic fungi. Among bark and ambrosia beetles, Anisandrus dispar Fabricius and Xylosandrus germanus Blandford (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) are the most prevalent pest species all over the world (Oliver and Mannion 2001; Rabaglia et al. 2006; Ranger et al. 2016; Ak 2016). These pests are polyphagous and damage many perennial plants, including hazelnut (Bucini et al. 2005 and Ak et al. 2011).

A. dispar, X. germanus, and Xyleborinus saxesenii Ratzeburg are among the significant pests of hazelnut in Turkey (Ak 2016; Tuncer et al. 2017). These beetles cause crop losses by draining hazelnut branches and trees, especially in orchards at coastline of the Black Sea region in the country, which has high groundwater level (Saruhan and Akyol 2012).

Ambrosia beetles are difficult to control as their majority of life is spent under the bark of host trees (Reding et al. 2010). Therefore, insecticides can be ineffective against these beetles unless applied repeatedly or application timing coincides with flight time of the beetles (Oliver and Mannion 2001). Keeping in view these facts, effective and eco-friendly alternative control methods are inevitable in the country. Considering environmental conditions, use of entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) against A. dispar and X. germanus could be an alternative pest management approach in hazelnut orchards. The Black Sea region receives frequent rainfall and has high humidity and low temperatures per year, and these environmental conditions are ideal for the development of entomopathogenic fungi (Erper et al. 2016).

EPF such as Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill., Lecanicillium spp., Metarhizium anisopliae (Metch) Sorok, and Isaria fumosorosea Wize are used to control several pests around the world (Zimmermann 2007a, 2007b, 2008; Gurulingappa et al. 2011). Among those, I. fumosorosea was known as Paecilomyces fumosoroseus since 30 years, and then transferred to the genus Isaria (Zimmermann 2008).

EPF are important control agents of ambrosia beetles, as they may affect larvae in the galleries as well as adults outside the host trees (Castrillo et al. 2013). Some EPF have been found associated with ambrosia and bark beetles (Popa et al. 2011). Several studies have indicated that B. bassiana, M. anisopliae, and I. fumosorosea were effective against ambrosia beetles such as Trypodendron lineatum Olivier, X. germanus, Xylosandrus crassiusculus (Motschulsky), and Xyloborus glabratus Eichhoff (Castrillo et al. 2011, 2013 and 2015). Castrillo et al. (2011) found that commercial strains of B. bassiana and M. anisopliae induced high mortality in females of X. germanus, as 100% of their offspring larvae was infected.

The present study shed a light on the efficacy of two conidial concentrations (1 × 106 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1) of I. fumosorosea TR-78-3 against females of A. dispar and X. germanus, using two different application methods under laboratory conditions.

Material and methods

Insect cultures

Hazelnut orchards in Terme district of Samsun province, Turkey, were surveyed to collect hazelnut branches infested with A. dispar and X. germanus during March–April 2017. The infested branches were cut into 30-cm-long pieces, kept in plastic boxes (20 × 25 × 40 cm), and directly transferred to the laboratory (Ondokuz Mayıs University, Agriculture Faculty, Plant Protection Department, Samsun, Turkey). The branches were dissected by pruning scissors. Only females were collected from the galleries and inspected under Leica EZ4 stereomicroscope at × 40–70 magnification to separate healthy adults of A. dispar and X. germanus for use in bioassays. As in many EPF studies (Castrillo et al. 2015), only females were used in the present study. The males are rare in the population of ambrosia beetles (about 10:1 in favor of female), flightless, and rarely seen outside the gallery (Ranger et al. 2016).

Fungal isolate

EPF isolate TR-78-3 used in the present study was isolated from the pupae of Hyphantria cunea (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) commonly called fall webworm, collected from hazelnut orchards (Samsun, Turkey). Single-spore isolate was obtained by serial dilution (Dhingra and Sinclair 1995) and identified as I. fumosorosea by Dr. Richard A. Humber, USDA-ARS Biological Integrated Pest Management Unit. The fungus was prepared and stored at 4 °C on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA; Merck Ltd., Darmstadt, Germany) slants and also in cryogenic tubes containing 15% glycerol at − 80 °C. The isolate was deposited in the fungal culture collection of the Mycology Laboratory, Ondokuz Mayıs University, Agriculture Faculty, Plant Protection Department, Samsun, Turkey, and in the USDA-ARS Entomopathogenic Fungal Culture Collection in Ithaca, NY (ARSEF 12173).

Inoculum of I. fumosorosea

EPF, I. fumosorosea isolate TR-78-3 was plated on SDA and incubated (Binder KBWF 240; Germany) at 25 °C for 15 days. Conidia were harvested by sterile distilled water containing 0.02% Tween 20. Mycelia were removed by filtering conidia suspensions through four layers of sterile cheese cloth. The suspensions of conidia were adjusted to 1 × 106 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1, using a Neubauer hemocytometer under Olympus CX31 compound microscope (Olympus America Inc., Lake Success, NY) (Saruhan et al. 2015).

Conidial germination assessment

The viability of conidia of the isolate was determined. A conidial suspension was adjusted to 1 × 104 conidia ml−1, and 0.2 ml was sprayed onto Petri dishes (9 cm diameter), containing potato dextrose agar (PDA; Merck Ltd., Darmstadt, Germany). The Petri dishes were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C. After 24 h of incubation, percentage of germinated conidia was determined, using Olympus CX-31 compound microscope at × 400 magnification. Conidia were regarded as germinated when they produced a germ tube at least half of the conidial length (Saruhan et al. 2015). The germination ratios of the fungus were determined by examining a minimum of 200 conidia from each of three replicate dishes.

Bioassays

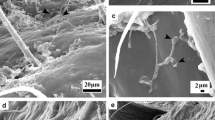

Females of A. dispar and X. germanus were surface disinfected with 70% ethanol for 10 s and placed on an autoclaved filter paper for drying (Castrillo et al. 2013). The hazelnut branches (5 cm length and 1 cm diameter), used in the bioassays, were sterilized in autoclavable polyethylene bags (30 × 30 cm) for 1 h at 121 °C on two successive days. The Petri dishes that were lined with the moist sterile filter paper at the bottom were used in all experiments. The bioassays were carried out by using two different methods; the first, two conidial suspensions (1 × 106 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1) of the isolate were directly sprayed to females of A. dispar and X. germanus in the Petri dishes (2 ml per dish), using a Potter spray tower (Burkard, Rickmansworth, Hertz UK), and a sterilized hazelnut branch was placed in each Petri dish, and the second method, same amount of conidial suspensions of the fungus was applied to Petri dishes containing a sterilized hazelnut branch with same method, and then the sterile females were released in the dishes. Control Petri dishes were treated by sterile distilled water (2 ml) containing 0.02% Tween 20. The spray tower was disinfected by 70% ethanol and sterile distilled water after each application. All Petri dishes were loosely covered by Parafilm and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C and 75 ± 5% RH, 16:8 h light to dark period in a Binder incubator (Model KBWF 240; Germany). The experiment had five replications (a Petri dish each), by placing five insects in each dish. Different groups of insects were used for 8 successive days, provided independence of the observations on mortality on over time (Robertson et al. 2007). The dead adults were removed daily and immediately surface disinfected by dipping in 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 3 min and in 70% ethanol for 3 min. Then, the dead insects were washed three times in sterile distilled water and placed in a moisture chamber. Mortality rates were confirmed by examination of hyphae on the cadavers under Leica EZ4 stereomicroscope (Kocaçevik et al. 2016).

Statistical analysis

Abbott correction was not used since mortality was lower more than 5% in the control. Independent time-mortality data from bioassays were analyzed by Probit analysis program (POLO-PLUS Ver.2.0) to calculate 50% (LT50) and 90% (LT90) lethal time. In lethal time analysis, Log-Probit analysis calculations were considered. Slopes of regression lines were compared to each other by their standard errors. LT50 and LT90 values of two application methods and two conidial suspensions were compared based on overlapping of 95% confidence intervals.

Results and discussion

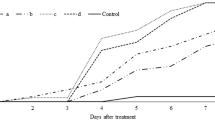

Conidia viability of I. fumosorosea isolate TR-78-3 was assessed before bioassays, and approximately (100%) germination was obtained. The LT50 values of 1 × 106 conidia ml−1 for A. dispar were 6.92 and 6.66 days for branch and insect application, respectively. Correspondent LT90 values, for the same concentration, were 11.16 and 10.57 days. The LT50 values of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 were 4.76 and 4.78 days, while the LT90 values were 6.49 and 5.94 days for branch and insect application methods, respectively (Table 1). The isolate tested against A. dispar resulted in increasing mortality rate, starting from day 4 in all application methods, with both tested concentrations. The efficacy of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 on A. dispar increased rapidly; by days 6 and 8, the mortality rates attained 75–90 and 100% in both methods, respectively. Nevertheless, the efficacy of 1 × 106 conidia ml−1 of the isolate was lower than that of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 (Fig. 1). In addition, all applications of I. fumosorosea caused (100%) mycosis on dead females of A. dispar. Kushiyev et al. (2017) estimated the LT50 and LT90 values of M. anisopliae TR-106 isolate at 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 concentration on females of A. dispar as 4.03 and 5.39 days at branch application and 3.67 and 4.22 days at insect application, respectively. Additionally, M. anisopliae TR-106 isolate applied with two methods against the beetle caused 100% mortality and about 95% mycosis after 8 days.

The LT50 values of (1 × 106 conidia ml−1) the isolate applied to X. germanus were 7.81 and 7.02 days in branch and insect application methods, respectively. Correspondent LT90 values were 11.03 and 11.46 days. The LT50 and LT90 values of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 of the isolate were 5.11 and 7.89 days for branch application method, while they were 4.18 and 5.62 days for insect application method (Table 2). The tested isolate caused mortality against X. germanus by day 4 in all treatments, except the 1 × 106 conidia ml−1 at the branch application method. High concentration (1 × 108 conidia ml−1), using insect application method caused 40% mortality rate by day 4, reaching 100% by day 7. Likewise in the branch application method, an increasing mortality rate was observed by day 4, raised to 70% by day 6 and 90% by day 8. Conversely, efficacy of the low concentration (1 × 106 conidia ml−1) remained lower than that of the high concentration of the isolate (Fig. 2). Moreover, I. fumosorosea TR-78-3 isolate caused 95–100% mycosis on dead females of X. germanus. Similarly, Tuncer et al. (2016) reported that LT50 and LT90 values of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 of B. bassiana TR-217 isolate against female adults of X. germanus were 5.96 and 11.79 days for branch method and 6.03 and 10.80 days for direct insect spray method.

As a result, the LT50 and LT90 values in the present study decreased with increasing conidial concentration of the isolate at all applications. However, comparisons of the confidence intervals indicated insignificant differences between LT90 values at both concentrations against females of X. germanus in branch application method. In addition, the isolate caused (100%) mortality rate with (1 × 108 conidia ml−1) in both methods by day 8 after inoculation against females of A. dispar. Same concentration of the isolate resulted to 90 and 100% mortality rate of X. germanus by day 8, in the branch and insect application methods, respectively. Some researchers have reported that the efficacy of EPF increases at high concentrations, which shorten the time required for insect mortality (Kocaçevik et al. 2016). Similarly, Tuncer et al. (2016) and Kushiyev et al. (2017) found that LT50 and LT90 values of M. anisopliae TR-106 and B. bassiana TR-217 isolates applied to females of A. dispar and X. germanus decreased by increasing conidial concentration. The present study also indicated that all applications of I. fumosorosea caused 100 and 95–100% mycosis on dead females of A. dispar and X. germanus, respectively. Nevertheless, Demir et al. (2013) stated that I. fumosorosea isolate caused mortality to Plagiodera versicolora Laicharting (Chrysomelidae), but did not produce mycosis on dead cadavers.

In the present study, significant difference was observed between the two application methods for 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 applied to X. germanus; however, there was no difference between the methods for all other applications (P > 0.05). Castrillo et al. (2015) reported insignificant differences in the mortality rates of X. glabratus females, exposed to B. bassiana strain (GHA) and I. fumosorosea strains (Ifr 3581 and PFR), by dipping in fungal suspension or placing on treated avocado branches. Tuncer et al. (2016) investigated the efficiency on insect and branch treatments of M. anisopliae TR-106 and B. bassiana TR-217 isolates at 1 × 106 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 against females of X. germanus and found insignificant differences between application methods and LT50 and LT90 values. In another study, Castrillo et al. (2013) demonstrated that B. bassiana (GHA and Naturalis) and M. anisopliae strain (F52) applied to females of X. crassiusculus caused 77, 96, and 79% mortality rates, respectively 5 days after treatment. Moreover, they stated that the females exposed to beech stems treated with same entomopathogen strains at 1 × 107 conidia ml−1 had lower survival rates.

EPF can be effective when applied directly on the insect or when the insect contacts the applied surface. Moreover, they provided a good potential control for some pests living in wood of trees, such as ambrosia and bark beetles, as they could also be transported into the gallery by infected individuals (Castrillo et al. 2013). Castrillo et al. (2011) determined that treated females of X. germanus with commercial strains of B. bassiana (Naturalis and GHA) and M. anisopliae (F52) caused significantly higher mortality rates compared to control, and reduced gallery formation and brood production in rearing tubes. They also stated that some treated females had 100% infected broods. Treated male adults transferred fungal inocula to untreated females which reduced their breeding activity by 20% (Prazak 1991). In summary, EPF did not only cause mortality of adult beetles outside in the host trees but also decreased beetles’ population through infecting next-generation broods in the galleries.

Sevim et al. (2013) indicated that EPF were more likely to have ecological compatibility with pests due to their geographical locations and habitats. In addition, The Middle and Eastern Black Sea region, which has largest hazelnuts growing area of Turkey, has favorable environmental conditions to use EPF in biocontrol of A. dispar and X. germanus, because it is rainy and humid and has low annual temperatures (Erper et al. 2016).

Conclusions

The present study showed that the EPF, I. fumosorosea isolate TR-78-3, seemed to be a promising biological control agent against A. dispar and X. germanus. However, further studies are necessary to evaluate the efficacy of the isolate on the pests under field conditions.

References

Ak K (2016) Comparison of sticky and non-sticky traps against harmful shothole borers (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in hazelnut orchards. Anadolu J Agr Sci 31(1):165–170

Ak K, Saruhan I, Tuncer C, Akyol H, Kiliç A (2011) Ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) species and their damage ratios in Kiwi orchards of Ordu Province. Turk bull Entomol 1(4):229–234

Bucini D, Balestra GM, Pucci C, Paparatii B, Speranza S, Zolla CP, Varvaro L (2005) Bio-ethology of Anisandrus dispar F. and its possible involvement in Dieback (Moria) diseases of hazelnut (Corylus avelana L.) plants in Central Italy. Acta Hortic 686:435–443

Castrillo D, Dunlap CA, Avery PB, Navarrete J, Duncan RE, Jackson MA, Behle RW, Cave RD, Crane J, Rooney AP, Peña JE (2015) Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents for the vector of the laurel wilt disease, the red bay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Biol Control 81:44–50

Castrillo LA, Griggs MH, Ranger CM, Reding ME, Vandenberg JD (2011) Virulence of commercial strains of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium brunneum (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) against adult Xylosandrus germanus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and impact on brood. Biol Control 58:121–126

Castrillo LA, Griggs MH, Vandenberg JD (2013) Granulate ambrosia beetle, Xylosandrus crassiusculus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), survival and brood production following exposure to entomopathogenic and mycoparasitic fungi. Biol Control 67:220–226

Demir İ, Kocaçevik S, Sönmez E, Demirbağ Z, Sevim A (2013) Virulance of entomopathogenic fungi against Plagiodera versicolora (Laicharting, 1781) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Afr J Agric Res 8:2016–2021

Dhingra OD, Sinclair JB (1995) Basic plant pathology methods, 2nd edn. CRC press, 62, Boca Raton, p 751

Erper I, Saruhan I, Akca I, Aksoy HM, Tuncer C (2016) Evaluation of some entomopathogenic fungi for controlling the Green Shield Bug, Palomena prasina L. (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Egyptian J Biol Pest Contr 26(3):573–578

Gurulingappa P, Mcgee P, Sword GA (2011) In vitro and in plants compatibility of insecticides and the endophytic entomopathogen, Lecanicillium lecanii. Mycopathologia 172:161–168

Hall FR, Ellis MA, Ferree DC (1982) Influence of fire blight and ambrosia beetle on several apple cultivars on M9 and M9 interstems. Ohio State Univ Res Circulation 272:20–24

Harrington TC (2005) Ecology and evolution of mycophagous bark beetles and their fungal partners. In: Vega FE, Blackwell M (eds) Insect-fungal associations: ecology and evolution. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 257–292

Hulcr J, Dunn RR (2011) The sudden emergence of pathogenicity in insect fungus symbioses threatens naive forest ecosystems. Proc R Soc Lond B 278:2866–2873

Kessler KJ (1974) An apparent symbiosis between Fusarium fungi and ambrosia beetles causes canker on black walnut stems. Plant Dis Rep 58:1044–1047

Kocaçevik S, Sevim A, Eroğlu M, Demirbağ Z, Demir I (2016) Virulence and horizontal transmission of Beauveria pseudobassiana S.A. Rehner & Humber in Ips sexdentatus and Ips typographus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Turk J Agric For 40:241–248

Kushiyev R., Tuncer C., Erper I., Saruhan I. (2017). Effectiveness of entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana against Anisandrus dispar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). IX. International Hazelnut Congress Abstract Book. 15–19 August, Samsun, Turkey, p 178

Norris DM (1979) The mutualistic fungi of the Xyleborini beetles. In: Batra LR (ed) Insect-fungus symbiosis: nutrition, mutualism, and commensalism. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 53–63

Oliver JB, Mannion CM (2001) Ambrosia beetle (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) species attacking chestnut and captured in ethanol-baited traps in middle Tennessee. Environ Entomol 30:909–918

Popa V, Deziel E, Lavallee R, Bauce E, Guertin C (2011) The complex symbiotic relationship of bark beetles with microorganisms: a potential practical approach for biological control in forestry. Pest Manag Sci 68:963–975

Prazak RA (1991) Studies on indirect infection of Trypodendron lineatum Oliv with Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. Z Angew Entomol 111:431–441

Rabaglia RJ, Dole SA, Cognato AI (2006) Review of American Xyleborina (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) occurring North of Mexico, with an illustrated key. Ann Entomol Soc Am 99:1034–1055

Ranger CM, Reding ME, Schultz PB, Oliver JB, Frank SD, Addesso KM, Chong JH, Sampson B, Werle C, Gill S, Krause C (2016) Biology, ecology, and management of nonnative ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in ornamental plant nurseries. J Int Pest Manag 7(1):9 1–23

Reding M, Oliver J, Schultz P, Ranger C (2010) Monitoring flight activity of ambrosia beetles in ornamental nurseries with ethanol-baited traps: influence of trap height on captures. J Environ Hortic 28:85–90

Robertson JL, Russell RM, Preisler HK, Savin E (2007) Bioassays with arthropods, 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, p 199

Saruhan I, Akyol H (2012) Monitoring population density and fluctuations of Anisandrus dispar and Xyleborinus saxesenii (Coleoptera: Scolytinae: Curculionidae) in hazelnut orchards. Afr J Biotechnol 11(18):4202–4207

Saruhan I, Erper I, Tuncer C, Akca I (2015) Efficiency of some entomopathogenic fungi as biocontrol agents against Aphis fabae Scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Pak J Agric Sci 52(2):273–278

Sevim A, Demir I, Sonmez E, Kocacevik S, Demirbag Z (2013) Evaluation of entomopathogenic fungi against the sycamore lace bug, Corythucha ciliata (Say) (Hemiptera: Tingidae). Turk J Agric For 37:595–603

Six DL (2003) Bark beetle–fungus symbioses. In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA (eds) Insect symbiosis. NY, CRC Press, New York

Tuncer C, Knížek M, Hulcr J (2017) Scolytinae in hazelnut orchards of Turkey: clarification of species and identification key (Coleoptera, Curculionidae). ZooKeys 710:65–76

Tuncer C, Kushiyev R, Saruhan I, Erper I (2016) Determination of the effectiveness of entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana against Xylosandrus germanus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), Turkey 6th Plant Protection Congress with International Participation, p 127

Zimmermann G (2007a) Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocont Sci Technol 17:553–596

Zimmermann G (2007b) Review on safety of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Biocont Sci Technol 17:879–920

Zimmermann G (2008) The entomopathogenic fungi Isaria farinosa (formerly Paecilomyces farinosus) and the Isaria fumosorosea species complex (formerly Paecilomyces fumosoroseus): biology, ecology and use in biological control. Biocont Sci Technol 18:865–901

Acknowledgements

The authors extend thanks to Dr. Richard A. Humber for his kind help with the morphological characterizations of the entomopathogenic fungus. Rahman Kushiyev is thankful to the Scientific and Technological Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) for providing fellowship under 2215 Graduate Scholarship program for international students.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available at the end of the article, and the materials used in this work are of high quality and grade.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IE, RK, CT, IOO, and IS designed the study, supervised the work, and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. IE, RK, IOO, and IS carried out the experiments. CT analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kushiyev, R., Tuncer, C., Erper, I. et al. Efficacy of native entomopathogenic fungus, Isaria fumosorosea, against bark and ambrosia beetles, Anisandrus dispar Fabricius and Xylosandrus germanus Blandford (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Egypt J Biol Pest Control 28, 55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-018-0062-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-018-0062-z