Abstract

Background

Gall crabs were described 150 years ago, but little is known about their biology, ecology, and taxonomy. Studying the breeding season can facilitate the understanding of the adaptive strategies and reproductive potential of gall crab and its relationship with the environment and other species.

Results

Growth and reproductive biology of the coral gall crab, Hapalocarcinus marsupialis, were studied at the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, Egypt. A total of 209 specimens were collected from different reef depths during 2014. The relationship between the carapace width (CW) and total body wet weight (W) was represented as Log W = 0.190 + 2.87 Log CW. Growth generally shows a negative allometric pattern, while the relation between CW and the carapace length (CL) is represented by Log CL = 0.019 + 1.009 Log CW. This relation is linear and shows an isometric regression coefficient. The overall value for “kn” is varied from 0.8 to 1.24, with an average of 1.11 ± 0.13, which denotes fitness for females. H. marsupialis shows clear sexual dimorphism and has a lengthy definite breeding season characterized by carrying eggs throughout the year. The incubated eggs are semispherical in shape, with diameter ranges according to maturity stages between 10 and 50 μm. The color of incubated eggs is also varied according to the developmental stage. Most females attain sexual maturity between 2.0- and 2.49-mm CW. Juveniles were recorded during each month of the year except in January and October. Fecundity varied from 10 to 740 eggs, with an average of 230 ± 173 eggs/female, showing linear relation with the carapace width. A significant relationship between the carapace width and fecundity was represented by Log F = 0.22 + 2.39 Log CW.

Conclusion

The present study emphasized the reproductive biology of H. marsupialis and explained the size structure, sexual dimorphism, breeding season, fecundity, size at first maturity, and juvenile’s recruitments in the three selected sites Dahab, Nuweiba, and Taba along the Gulf of Aqaba.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Brachyuran decapods are abundant among branching corals (Patton, 1974; Castro, 1976) especially in the Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae families (Abele, 1984). The coral gall crab, Hapalocarcinus marsupialis, was described for the first time living on corals (Stimpson, 1859). The ability of the crab to initiate gall development in its host coral was documented by Verrill (1867). H. marsupialis is widely distributed on the western shores of the Indian Ocean from the Red Sea to South Africa and extending through the tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans to the western coasts of central and south America (Kropp, 1990). Kotb and Hartnoll (2002) studied the reproduction of gall crab H. marsupialis in Stylophora pistillata and divided the coral galls into five stages, where the late stages contained larger and matured crabs and had a high crab production of ovigerous females. The physiological state of the gall crabs declines the growth rates and may increase mortality due to feed reduction or reproduction diversion (Hartnoll, 2006).

Reproductive periods for most brachyuran crabs can be estimated by gonadal development and by the ratio of ovigerous females throughout the year (Pillay & Nair, 1971; Murai et al., 1987; Mouton, Mouton, & Felder, 1995; Rodríguez et al., 1997; Chacur and Negreiros-Fransozo, 2001; Flores et al., 2002; Negreiros-Fransozo et al., 2002; Colpo and Negreiros-Fransozo, 2003). The size at sexual maturity, based on external morphological features, can sometimes be misestimated when the curves for immature and mature specimens overlap (Somerton, 1980a, b). In some species, morphological sexual maturity does not coincide with physiological sexual maturity (Conan and Comeau, 1986; Choy, 1988 and Fontelles-Filho, 1989). The sexual maturity is related to the presence of mature gonads (producing gametes). Thus, to estimate the size at first maturation of a brachyuran, the degree of gonad development beyond the external morphological features should be considered (Watson, 1970; Brown and Powell, 1972).

Males that look free-living may move from one colony to another to mate or share a gall with a female (Castro, 1976; Warner, 1977; McCain and Coles, 1979 and Vehof et al., 2014). Cryptochirid female crabs inhabit cavities for breeding their entire lives. They have an allometric growth of their abdomen that forms a brood pouch under the cephalothorax. This feature is a synapomorphic character of the Cryptochiridae family that can be found among female pea crabs (family Pinnotheridae; Becker, 2010). Brachyuran crabs diversified their shape to maximize egg production and offspring survivorship (López-Greco et al., 2000). The present study aims to study the reproductive biology of H. marsupialis, with emphasis on size structure, sexual dimorphism, breeding season, fecundity, size at first maturity, and juvenile recruitments in the three selected sites, Dahab, Nuweiba, and Taba along the Gulf of Aqaba.

Methods

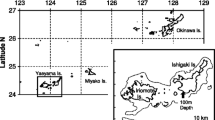

A total of 209 specimens of gall crab H. marsupialis (165 females, 42 juveniles, and 2 males) were collected from different depths ranging from 0.5 to 3 m (the reef flat, reef edge, and reef slope) at three widely geographically separated sites along the Gulf of Aqaba. The sites chosen are at Dahab (34° 54′ 982″ E–28° 60′ 55″ N), Nuweiba (34° 64′ 396″ E–28° 88′ 119″ N), and Taba (34° 83′ 057″ E–29° 42′ 189″ N) (Fig. 1).

The period of this study extended from January to December 2014. Female crabs were observed within the branches of stony corals S. pistillata (family Pocilloporidae) at the shoreward side of the reef flat, reef edge, and reef slope, while fewer galls were observed at the seaward side of the reef flat. Specimens of galls were randomly collected by using long-nose pliers to break off the branches with galls at their ends, without damaging coral colonies. Samples were immediately preserved in 10% formalin solution mixed with 5% alcohol and 5% glycerol and kept in labeled plastic containers provided with the date, site of collection, and coral species (Kotb and Hartnoll, 2002). At the laboratory, examination and measurements were taken as soon as possible to limit changes in color of the crab or its body contents.

The collected specimens were identified to the species level according to Serene (1962 and 1966), Kropp (1990), and Wei, Hwang, Tsai, and Fang (2006). The total body wet weight was taken to the nearest 0.01 g using an electric balance with an accuracy of 0.01 g after blotting excess water with absorbent tissues. The carapace length (CL) and carapace width (CW) were measured to the nearest 10 μm using an eyepiece micrometer according to Kotb and Hartnoll (2002).

The relationships between CW and the total body weight (W) were calculated according to the following equation:

where Y = body weight in milligrams, X = carapace width in millimeters, a = constant and equal to the intercept of the straight line with the Y-axis, and b = the coefficient of allometry. The method of least squares was used, and the coefficients (a) and (b) were calculated by plotting log Y against log X according to Hile (1936), Bagenal and Tesch (1978), and Le Cren (1951) where:

The well-being or relative condition factor “Kn” was calculated according the following formula:

where W = observed weight and W′ = calculated weight from the width-weight relationship.

Eggs were carefully removed from the pleopods and counted under the stereomicroscope (Choy, 1985). Egg diameters were measured to the nearest micrometer using a stereo-binocular microscope (PZO Warszawa) provided with graduated screen. The incidence of ovigerous females was noticed and used to determine the breeding season. The size of incubated eggs was measured at various developmental stages. The fecundity was calculated by counting incubated eggs according to Subramoniam (1982). The relationship between the egg number or absolute fecundity and female carapace width was calculated according to the following formula:

where F = absolute fecundity and CW = female carapace width.

Results

Morphometric relationships

A total of 165 female specimens of H. marsupialis were used for studying the relationship between crab CW and W. The carapace width varied from 2.5 to 5.9 mm, and the crab wet weight ranged from 6 to 230 mg. The relationship between the carapace width and body weight was represented by the following equation:

It is a curvilinear relation with a high correlation coefficient (r = 0.98) and negative allometric regression coefficient (b = 2.87) with an intercept of Y-axis “a” = 0.190 (Table 1, Fig. 2). The value of “b” denotes a faster increase in the carapace width than the body weight.

On the other hand, the relationship between the CW and CL of H. marsupialis was calculated and represented (Fig. 3) by the following equation.

This relation is linear and shows an isometric regression coefficient (b = 1.0096) (slope = 1.0, P < 0.001), the carapace becoming relatively wider and shorter with increasing size, the intercept of Y-axis “a” = 0.019, and high correlation coefficient “r” = 0.91. A highly significant difference was found between the slopes of this relationship.

The results of the relative condition factor “Kn” for different size classes of the females of H. marsupialis are given in Table 1 and represented in Fig. 4. The overall value for “kn” is varied from 0.8 to 1.24, with an average of 1.11 ± 0.13, which denotes fitness for females.

Reproduction

Sexual dimorphism

Morphologically, abdominal appendages are the main sex character for rapid differentiation between mature males and females of H. marsupialis. Mature males have a relatively tapering abdomen provided with two unequal pairs of uniramus pleopods. In contrast, the female’s abdomen is more flattened, semicircular, provided with four biramous pleopods, and usually fringed with entangled setae in maturing females, particularly during spawning season.

Spawning season

The spawning season of H. marsupialis was determined by the appearance of ovigerous females carrying clutches of fertilized eggs on their pleopods. H. marsupialis has a lengthy definite breeding season and carries eggs throughout the year. The percentages of ovigerous females recorded 100% during December and decline to the lowest value (57.14%) during October (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Immature ovaries were translucent, difficult to see, and had very small ova (diameter < 0.1 mm). Developing ovaries were pale cream or yellow, had a mean ova diameter of 0.32 mm, and ranged between 0.2 and 0.5 mm. Mature ovaries were pale orange with a mean ova diameter of 0.39 mm and ranged between 0.1 and 0.5 mm. A few specimens with orange ovaries had small ova, but their color was not a fully consistent index of maturity because the median diameter of incubating eggs was around 0.4 mm.

Incubated eggs

The incubated eggs are semispherical in shape, with the diameter range between 10 and 50 μm according to maturity stages (Table 3). The color of incubated eggs was varied according to the developmental stage. The color appears pale yellow for newly laid eggs (stage I), changing, as development proceeds, to yellow (stage II), bright yellow (stage III), orange (stage IV), and faint orange (for stage V). It is worth mentioning that the smallest females carrying eggs were collected throughout May and June (newly laid eggs) and the largest ones were collected throughout June (stage III). However, ovigerous females appeared throughout the year, indicating that the incubation period for this species may extend for 2 months. Ripening ovaries, evidence of mating, and production of eggs all serve as indices of sexual maturity; the production of eggs is an unambiguous sign functional maturity.

Maturity stages and spawning season

The onset of smallest ovigerous females was also taken for determining the first maturity size. Field collection showed that the smallest ovigerous female measured 2.4 × 2.4 mm (CW × CL), captured in June; this means that most females attain sexual maturity between the 2- and 2.49-mm CW classes. Table 2 displays the total number of collected specimens for both maturing females (ovigerous) and juveniles of H. marsupialis. The percentage of mature females is 79.7%, while juveniles are 20.3% recorded in all months except January and October. The lowest value of juveniles was 1 recorded during May, September, November, and December and the highest value was 17 recorded in June (Fig. 6). These results denote the relatively short period for juvenile metamorphosis after hatching and the short breeding season for this species.

Fecundity

The incubated eggs for 140 H. marsupialis females were counted. The egg number (fecundity) of these females was relatively low, varying from 10 to 740, with an average of 230.3 ± 172.8 eggs/female. The smallest ovigerous female 2.4 × 2.4 mm (CW × CL), collected in June, carried 150 eggs, all at stage (II), while the largest egg number was 740, at stage (IV),with size 4.0 × 3.6 mm (CW × CL) collected also in June, whereas the lowest egg number was 10 for sizes of 3.1 × 3.1 mm, 3.2 × 3.0 mm, and 4 × 3.9 mm and 3.9 × 3.3 mm (CW × CL), collected in May, June, and February, respectively.

The logarithmic relationship between the carapace width and total egg number or fecundity (F) was illustrated in Fig. 7 and represented by the following equation:

This relation is statistically significant, showing linear relation with low correlation coefficient “r” being 0.76 and negative allometric regression coefficient “b” = (2.39) (b < 3, p < 0.05) with positive intercept of Y-axis “a” = 0.22. The prevalence of maturity increased with size.

Discussion

The current study is considered the first investigation about biology of the coral gall crab, H. marsupialis, at the Egyptian coast of the Gulf of Aqaba. However, Mohammed and Yassien (2013) studied the distribution of H. marsupialis along Red Sea coast while Kotb and Hartnoll (2002) studied the biology of the coral gall crab H. marsupialis at the south of Hurghad. On the other hand, the reproductive biology of true crabs along the Egyptian coast of the Red Sea and the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba were well documented in several studies (El-Sayed, 1997, 2004; El-Sayed et al., 1998, 2011, 2014; Fouda, 2000). During the present investigation, H. marsupialis were recorded hosted to S. pistillata. This finding was concurrent with Fize and Serene (1957) and Mohammed and Yassien (2013).

In the present study, the relationships between the carapace width and weight of H. marsupialis showed negative allometry (b = 2.87). Bagenal and Tesch (1978) mentioned a similar result: that the isometric growth rate (b value) is ranged from 2.5 to 3.5, while an increase or decrease of the “b” value other than that range indicates allometric negative growth (b value < 2.5) or positive growth (b value > 3.5). However, Du-Preez and Mclachlan (1984) found isometric positive relationships between the carapace width and body weight of Portunus pelagicus and Ovalipes punctatus. The increments in the carapace width than weight for H. marsupials may be attributed to either environmental or biological factors particularly availability of food and breeding seasons (El-Sayed, 1997, 2004; Abd El-Razek, 2006; Josileen, 2011; Thirunavukkarasu and Shanmugam, 2011; Aydin, 2013).

The isometric growth rate was calculated between the carapace width and carapace length (regression coefficient; b = 1.009); this agrees with Kotb and Hartnoll (2002) on H. marsupialis. Hartnoll (1982) clarified that if the regression coefficient (b), which defines the type of allometric growth rates, exceeds 1, it gives positive allometry; if it equals 1, it is referring to the isometry; but if it is less than 1, it is indicating negative allometry. Du-Preez and Mclachlan (1984) recorded a positive allometric growth rate between these two variables for O. punctatus, while slight negative allometry in Telmessus cheiragonus and Telmessus acutidens was recorded by Urita (1936).

The results of relative condition factor “Kn” for the whole populations of H. marsupials females were varied from 0.8 to 1.24 and averaged 1.11 ± 0.13. This result agrees with the finding of El-Sayed, Fouda, Azab, and Ismail (2011) on Petrolisthes rufescens; Arab (2010) on Pachygrapsus marmoratus and Pachygrapsus transversus; Salem (2014) on Trapezia cymodoce; and Salem, Fouda, Al-Hammady, and El-Damhougy (2017) on Tetralia glaberrima. The values of Kn denote a well-being or fitness for the whole population, and measuring the well-being of crabs depend upon the relationship between the carapace width and total body weight. Similar results were recorded by El-Sayed (1992) on Leucosia signata and Eucrate crenata, Fouda (2000) on Leptodius exarartus and Metopograpsus messor, El-Sayed (2004) on L. exarartus, and Salem (2014) on T. cymodoce from the Red Sea.

There is a clear external morphological sexual dimorphism for H. marsupialis females, characterized by broad abdomens and provided with four pairs of segmented biramous pleopods, while males have an elongated tapering abdomen and two pairs of uniramus pleopods. This is in agreement with the results carried out on other brachyurans (Hartnoll, 1974 and 1982; Abd-Razek, 1987; El-Sayed, 1997 and 2004; De Lasting, Hall, & Potter, 2003; El-Sayed et al., 2011 and 2014 and Salem, 2014). Like most Red Sea brachyuran crabs, H. marsupials females carry eggs throughout the year; this agrees with Kotb and Hartnoll (2002). The frequencies of berried (gravid) or ovigerous females increased gradually, reaching its maximum during December. These results agree with Edwards and Emberton (1980); Wolodarsky and Loya (1980); Gotelli, Gilchrist, and Abele (1985); Costa (2000); and El-Sayed et al. (2014), but disagree with Erkan, Balkis, Kurun, and Tunali (2008) who mentioned that reproduction of Eriphia verrucosa is correlated with the changes in seawater temperature. However, the fluctuations in the percentage of appearance of ovigerous females may be attributed to the prevailing environmental fluctuations as recorded in the Red Sea (Hamed and Said, 2000) or to the availability of food (Fusaro, 1978; Fouda, 2000).

The color of incubated eggs is varied according to the developmental stage. The color appears pale yellow for newly laid eggs (stage I), changing, as development proceeds, to yellow (stage II), bright yellow (stage III), orange (stage IV), and faint orange (for stage V). This result confirms the finding of El-Sayed et al. (2014) on T. cymodoce from the Gulf of Aqaba where they reported that egg size shows a gradual decrease towards the late developmental stages, with a remarkable change in color, which appears pale yellow for newly laid eggs (stage I), changing, as development proceeds, to yellow (stage II), bright yellow (stage III), orange (stage IV), and faint orange (for stage V). Guillory and Hein (1997) mentioned that the color change is caused by absorption of the yellow yolk and development of dark pigment in the eggs and on the body of the embryos. The size of incubated eggs of H. marsupialis is relatively small, and these eggs decrease remarkably and vary between 10 and 50 μm in diameter. These measurements are nearly similar to those measured by Arab (2010) that was 33.6 μm in P. marmoratus and 27.5 μm in P. transversus and Kotb and Hartnoll (2002) on H. marsupialis (0.39 mm) at the Red Sea. However, Erkan et al. (2008) found different measurements of egg diameter of E. verrucosa (610 μm) at the Black Sea and El-Sayed et al. (2014) on T. cymodoce (131 μm) from the Gulf of Aqaba.

Eggs at different development stages were detected attached to the receptacle of the pleopods of ovigerous females at the same time. Guillory, Prejean, Bourgeois, Burdon, and Merrell (1996) found that fertilized eggs pass through the spermathecae and then attach to the receptacle of the pleopods. The stages of maturation for the incubated eggs in the present study are similar to those described by Guillory and Hein (1997) and El-Sayed (2004) on the xanthid crab, Leptodius exaratus, and El-Sayed et al. (2011) on the flattened porcelain crab, P. rufescens, from the Red Sea.

H. marsupialis females attain sexual maturity between 2- and 2.49-mm CW classes; these measurements agree with Kotb and Hartnoll (2002).The appearance of ovigerous females in determination of breeding seasons has been employed by several workers. Varadarajan and Subramoniam (1982) used ovigerous females for studying breeding of the tropical hermit crab, Clibanarius clibanarius. Lancaster (1990) used frequencies of ovigerous females in demarcating the breeding season of the hermit crab, Pagurus bernhardus. The presence of H. marsupialis ovigerous females with different developmental incubated egg stages throughout the year may indicate frequency of spawning during the same breeding season. Also, it may define the length of the incubation period, which may be up to 1 month (El-Sayed et al., 1998; Fouda, 2000; El-Sayed, 1997, 2004; Kotb and Hartnoll, 2002).

H. marsupialis juveniles were recorded during each month of the year except January and October. These results denote a relatively short period for juvenile metamorphosis after hatching and a short breeding season for this species. These agree with Fize (1956), who reported that the incubation period is 28 days, while other studies showed that there is a long duration for eggs of 0.4-mm diameter at a temperature around 25 °C and that a duration of 15 days or less is typical (Hartnoll, 1965; Warner, 1967; Wear, 1974). Overall, 80% of crabs > 3-mm CW were ovigerous, indicating that the period between successive incubations averaged about a quarter of the incubation period.

The fecundity of H. marsupialis was relatively low. These values are very close to the results of T. cymodoce (Salem, 2014) and H. marsupialis (Kotb and Hartnoll, 2002), but very low compared with those obtained by Arab (2010) on P. marmoratus from the eastern Mediterranean. The present results showed a decline of relative fecundity with increasing body mass. Hines (1982) reported such a decline for 12 out of 20 species analyzed. There are possible explanations in Hapalocarcinus for this reduction in relative fecundity. One is increasingly poor fertilization success as the sperm is depleted—this has been demonstrated in Chionoecetes (Sainte-Marie and Carriere, 1995). A second is the limitation of food supply via the small pores in the gall as the crab increases in size and energy requirement (Hines, 1982). It is worth mentioning that few egg numbers may be attributed to either egg loss, releasing larvae at the late stages, or beginning of spawning of new egg lay. Such as in most crustaceans and other animals, the reproductive investment was highly variable and varied with body size. Large decapods can produce 100,000 eggs in a single clutch (Hartnoll 2006), whereas the small-sized crustaceans have up to about 100 eggs (Sainte-Marie, 1991). The number of eggs produced was highly correlated with the size of females and was increased with an increase in the female’s size (Preston 1973, Gotelli et al., 1985; El-Sayed, 1997, 2004; El-Sayed et al., 1998, 2011; Fouda, 2000 and Aydin, 2013).

The linear relationship between fecundity (egg number) and carapace width was evident (allometric regression coefficient; b = 2.39). This result could be explained by the fact that crab size increased faster than egg number. This result agrees with that reported by several authors (Haynes et al., 1976; Atrill and Hartnoll, 1991; El-Sayed, 1992, 1997, 2004; Siddiqui and Ahmed, 1992; El-Sayed et al., 1998, 2014; Fouda, 2000; Kotb and Hartnoll, 2002; and El-Sayed et al., 2011) on several crab species. However, contrasting results were recorded by Gotelli et al. (1985).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study was performed to investigate the growth and reproductive biology of the coral gall crab, H. marsupialis, at the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, Egypt. Growth generally shows negative allometry. The overall value for “kn” denotes fitness for females. H. marsupialis has a lengthy definite breeding season and carries eggs throughout the year.

References

Abd El-Razek F. A. (1987). Some biological studies on the Egyptian crab Portunus pelagicus (L.) Proc. Zool. Soc. A. R. Egypt, 14, 223–233.

Abd El-Razek F. A. (2006). Population biology of the edible crab, Portunus pelagicus (Linnaeus.) from Bardawil Lagoon, Northern Sinai, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research, 32, 401–418.

Abele L. G. (1984). Biogeography, colonization and experimental structure of coral-associated crustaceans. In D. R. Strong, D. Simberloff, L. G. Abele, & A. B. Thistle (Eds.), Ecological communities: Conceptual issues and the evidence (pp. 123–137). Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Arab A. S. (2010). Population structure and biology of Lebanese rocky shore crabs Pachygrapsus marmoratus and P. transversus (Grabsidae). M.Sc. Thesis. Lebanon: Fac. of Arts and Science at the American University of Beirut.

Atrill M. J., & Hartnoll R. G. (1991). Aspects of the biology of the deep-sea crab, Geryon trispinosus from the Porcupine Seabight. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, 71, 311–328.

Aydin M. (2013). Length-weight relationship and reproductive features of the Mediterranean green crab, Carcinus aestuarii Nardo, 1847 (Decapoda: Brachyura) in the eastern Black Sea, Turkey. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 45(6), 1615–1622.

Bagenal T. B., & Tesch F. W. (1978). Age and growth. In W. E. Ricker (Ed.), Methods for assessment of fish production in fresh waters (pp. 101–136). Oxoford and Edinburgh: Blackwell.

Becker C. (2010). European pea crabs—Taxonomy, morphology, and hostecology (Crustacea: Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) (dissertation) (p. 180). Frankfurt/Main: Goethe-University.

Brown R. B., & Powell G. C. (1972). Size at maturity in the male Alaskan Tanner crab, Chionoecetes bairdi as determined by chela allometry, reproductive tract weight and size of procopulatory males. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 29(4), 423–427.

Castro P. (1976). Brachyuran crabs symbiotic with scleractinian corals: A review of their biology. Mcronesica, 12, 99–110.

Chacur M. M., & Negreiros-Fransozo M. L. (2001). Spatial and seasonal distribution of Callinectes danae (Decapoda, Portunidae) in Ubatuba Bay, São Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 21, 414–425.

Choy S. C. (1985). A rapid method for removing and counting eggs from fresh and preserved decapod crustaceans. Aquaculture, 48, 369–372.

Choy S. C. (1988). Reproductive biology of Liocarcinus puber and L. holsatus (Decapoda, Brachyura, Portunidae) from the Gower Peninsula, South Wales. Marine Biology, 9, 227–241.

Colpo K. D., & Negreiros-Fransozo M. L. (2003). Reproductive output of Uca vocator (Herbst, 1804) from three subtropical mangroves in Brazil. Crustaceana, 76, 1–11.

Conan G. Y., & Comeau M. (1986). Functional maturity and terminal molt of male snow crab Chionoecetes opilio. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 43, 1710–1719.

Costa T. M. (2000). Ecologia de caranguejos semiterrestres do genero Uca (Crustacea, Decapoda, Ocypodidae) deuma area de manguezal, em Ubatuba (SP), Ph.D. thesis (). Brazil: Universidade Estadual Paulista.

De Lasting S., Hall N., & Potter I. C. (2003). Influence of a deep artificial entrance channel on the biological characteristics of the blue swimmer crab Portunus pelagicus in a large microtidal estuary. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 295(1), 41–61.

Du-Preez H. H., & Mclachlan A. (1984). Biology of the three spot swimming crab Ovalipes punctatus 2, growth and moulting. Crustaceana Leiden, 47(2), 13–120.

Edwards A., & Emberton H. (1980). Crustacea associated with the scleractinian coral, Stylophora pistillata (Esper), in the Sudanese Red Sea. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 42, 225–240.

El-Sayed A. A. M. (1992). Biological studies on some brachyuran crabs (crustaceans) from Suez Canal, Ph. D. Thesis (). Cairo: Zoology Department Faculty of Science, Al- Azhar University.

El-Sayed A. A. M. (1997). The biology of spider crab, Menathius monoceros from the Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 1(1), 1–16.

El-Sayed A. A. M. (2004). Some aspects of the ecology and biology of the intertidal xanthid crab, Leptodius exaratus (H. Milne Edwards, 1834) from the Egyptian Red Sea Coast. Journal of the Egyptian-German Society of Zoology, 45(D), 115–139.

El-Sayed A. A. M., Saber S. A., El-Damhougy K. A., & Fouda M. M. A. (1998). The reproductive biology of Grapsid crab, Metopograpsus messor (Forskal, 1775) from Ain Sukhna, Gulf of Suez, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 2(4), 359–377.

El-Sayed A. A. M., Fouda M. M. A., Azab A. M., & Ismail M. I. (2011). Reproductive biology of the flattened porcelain crab Petrolisthes rufescens (Porcelanidae: Anomura: Crustacea) from Ain Sukhna, Gulf of Suez, Egypt. Al-Azhar Bulletin of Science, 22(2), 17–32.

El-Sayed A. A. M., El-Damhougy K. A., Hellal A. M., Salem M. S. A., Nasef A. M., & Salem S. S. (2014). Reproductive biology of the guard coral crab, Trapezia cymodoce (Family Trapeziidae) from Abu Galloum Protected Area, Gulf of Aqaba, South Sinai, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 18(2), 89–102.

Erkan M., Balkis H., Kurun A., & Tunali Y. (2008). Seasonal variations in the ovary and testis of Eriphia verrucosa (Forskål, 1775) (Crustacea: Decapoda) from Karaburun, SW Black Sea. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 40, 217–221.

Fize A. (1956). Observations biologiques sur les Hapalocarcinides.-Annals Faculte de Science Universite National Viet-Nam. Contributions ION, 22, 1–30.

Fize A., & Serene R. (1957). Les hapalocarcinides du VietNam. Memoirs du Institute Oceanographique de Nhatrang, 10, 1–202.

Flores A. A. V., Saraiva J., & Paula J. (2002). Sexual maturity, reproductive cycles, and juvenile recruitment of Perisesarma guttatum (Brachyura, Sesarmidae) at Ponta Rasa mangrove swamp, Inhaca Island, Mozambique. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 22, 143–156.

Fontelles-Filho A. A. (1989). Recursos pesqueiros: biologia e dinâmica populacional (296 p). Fortaleza: Imprensa Oficial do Ceará.

Fouda M. M. A. (2000). Biological and ecological studies on some crustacean decapods from the Suez Gulf, M. Sci. Thesis (). Cairo: Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Azhar University.

Fusaro G. (1978). Food availability and egg production; a field experiment with Hippa pacifica Dana (Decapoda: Hippidae). Pacific Scientific, 32(1), 17–23.

Gotelli N. J., Gilchrist S. L., & Abele L. G. (1985). Population biology of Trapezia spp. and other coral-associated decapods. Marine ecology progress Series, 21, 89–98.

Guillory V., & Hein S. (1997). Sexual maturity in blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus. Proceedings of the Louisiana Academy of Sciences, 59, 5–7.

Guillory V., Prejean E., Bourgeois M., Burdon J., & Merrell J. (1996). A biological and fisheries profile of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. LA Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Management Plan Series, 8(1), 210.

Hamed M. A., & Said T. O. (2000). Effect of pollution on the water quality of the Gulf of Suez. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 4(1), 161–178.

Hartnoll R. G. (1965). The biology of spider crabs: A comparison of British and Jamaican species. Crustaceana, 9, 1–16.

Hartnoll R. G. (1974). Variation in growth pattern between some secondary sexual characters in crabs (Decapoda: Brachyura). Crustaceana, 27(2), 131–136.

Hartnoll R. G. (1982). Growth. In L. G. Abele (Ed.), The biology of Crustacea, Vol. 2. Embryology, morphology, and genetics (pp. 111–197). New York: Academic Press.

Hartnoll R. G. (2006). Reproductive investment in Brachyura. Hydrobiologia, 557, 31–40.

Haynes E., Karinen J. F., Watson J., & Hopson D. J. (1976). Relation of number of egg and egg length to carapace width in the brachyuran crabs Chionoecetes bairdi and C. opelio from the south eastern Bering Sea and C. opilio from the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 33, 2592–2595.

Hile R. (1936). Age and growth of the Ciscoe leveichthys artedi (Le sueur.), in the lakes of the northeastern high lands, Wisconsin. Bulletin of Marine Fishes U.S, 48(19), 211–317.

Hines A. H. (1982). Allometric constraints and variables of reproductive effort in brachyuran crabs. Marine Biology, 69, 309–320.

Josileen J. (2011). Food and feeding of the blue swimming crab, Portunus pelagicus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Decapoda, Brachyura) along the coast of Mandapam, Tamil Nadu, India. Crustaceana, 84(10), 1169–1180.

Kotb M. M., & Hartnoll R. G. (2002). Aspects of the growth and reproduction of the coral gall crab Hapalocarcinus marsupialis. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 22(3), 558–566.

Kropp R. K. (1990). Revision of the genera of gall crabs (Crustacea: Cryptochiridae) occurring in the Pacific Ocean. Pacific Science, 44, 417–448.

Lancaster I. (1990). Reproduction and life history strategy of the hermit crab Pagurus bernhardus. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 70, 129–142.

Le Cren C. D. (1951). The length-weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weights and condition in the perch (Percafluviatilis). The Journal of Animal Ecology, 20, 201–219.

López-Greco L. S., Hernandez J. E., Bolanos J., Rodriguez J., Rodríguez E. M., & Hernandez G. (2000). Population features of Microphrys bicornutus Latreille, 1825 (Brachyura, Majidae) from Isla Margarita, Venezuela. Hydrobiologia, 439, 151–159.

McCain J. C., & Coles S. L. (1979). A new species of crab (brachyura, hapalocarcinidae) inhabiting pocilloporid corals in Hawaii. Crustaceana, 36, 81–89.

Mohammed T. A. A., & Yassien M. H. (2013). Assemblages of two gall crabs within coral species Northern Red Sea, Egypt. Asian Journal of Scientific Research, 6(1), 98–106.

Mouton E. C., Mouton J. R., & Felder D. L. (1995). Reproduction of the fiddler crabs Uca longisignalis and Uca spinicarpa in a Gulf of Mexico salt marsh. Estuaries, 18, 469–481.

Murai M., Goshima S., & Henmy Y. (1987). Analysis of the mating system of the fiddler crab Uca lactea. Animal Behavior, London, 35, 1334–1342.

Negreiros-Fransozo M. L., Fransozo A., & Bertini G. (2002). Reproductive cycle and recruitment period of Ocypode quadrata (Decapoda: Ocypodidae) at a sandy beach in southeastern Brazil. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 22, 157–161.

Patton W. K. (1974). Community structure among the animals inhabiting the coral Pocillopora damicornis at Heron Island, Australia. In W. B. Vernberg (Ed.), Symbiosis in the sea (pp. 219–243). Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Pillay K. K., & Nair N. B. M. (1971). The annual reproductive cycles of Uca annulipes, Portunus pelagicus and Metapenaeus affins (Decapoda, Crustacea) from the south-west of coast. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India, 11, 152–166.

Preston E. M. (1973). A computer simulation of competition among five sympatric congeneric species of xanthid crabs. Ecology, 54, 469–483.

Rodríguez A., Drake P., & Arias A. M. (1997). Reproductive periods and larval abundance patterns of the crabs Panopeus africanus and Uca tangeri in a shallow inlet (SW Spain). Marine Ecology Progress Series, 149, 133–142.

Sainte-Marie B. (1991). A review of the reproductive bionomics of aquatic gammaridean amphipods: Variation of life history traits with latitude, depth, salinity and superfamily. Hydrobiologia, 223, 189–122.

Sainte-Marie B., & Carriere C. (1995). Fertilisation of the second clutch of eggs of snow crab, Chionoecetes opilio, from females mated once or twice after their molt to maturity. Fisheries Bulletin (U.S.), 93, 759–764.

Salem, S., 2014. Biological studies on some marine invertebrates and their relation with coral reefs at Abu Galum Protected Area, Gulf of Aqba, South Sini, Egypt, M.Sc. Thesis, marine biology, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

Salem S. S., Fouda M. M., Al-Hammady M. A., & El-Damhougy K. A. (2017). Biometric relationships and condition factor of Tetralia glaberrima Herbst, 1790, Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, Egypt. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 2017, 5(2), 691–698.

Serene R. (1962). Species of Cryptochirus of Edmondson 1933 (Hapalocarcinidae). Pacific Scientific, 16, 30–41.

Serene, R., 1966. Note sur la taxonomie et la distribution geographique des Hapalocarcinidae (Decapoda Brachyura). Proc. Symp. Crustacea, Ernakulam, Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India, 12-15 Jan 1965, Part I: 395-398.

Siddiqui G., & Ahmed M. (1992). Fecundities of some marine brachyuran crabs from Karachi (Pakistan). Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 24(1), 43–45.

Somerton D. (1980a). A computer technique for estimating the size of sexual maturity in crabs. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 37, 1488–1494.

Somerton D. (1980b). Fitting straight lines to Hiatt growth diagrams: A re-evaluation. Journal du Conseil / Conseil Permanent International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 39, 15–19.

Stimpson W. (1859). Hapalocarcinus marsupialis, a remarkable new form of brachyurous crustacean on the coral reefs of Hawaii. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History, 6, 412–413.

Subramoniam T. (1982). Determination of reproductive periodicity in the intertidal mole crab, Emerita asiatica. In T. Subramoniam (Ed.), Manual of research methods for marine invertebrates and reproduction (vol. No.9, pp. 163–167). Cochin: CMFRI Publication.

Thirunavukkarasu N., & Shanmugam A. (2011). Length-weight and width-weight relationships of mud crab Scylla tranquebarica (Fabricius, 1798). Journal of Marine Biological Association of India, 53(1), 142–144.

Urita T. (1936). Dimensional, morphological and zoogeographical study of Japanese crabs of the genus Telmessus. Sci. Rep. Tohoku Imp. Univ. Sendai, Ser.4, 11, 69–89 USA. Journal of Shellfish Research 3 (2): 117–128.

Varadarajan S., & Subramoniam T. (1982). Reproduction of the continuous breeding tropical hermit crab, Clibanarius clibanarius. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 8, 197–201.

Vehof, J; Van der Meij, S.E.T.; Türkay, M, and Becker, C., 2014. Female reproductive morphology of coral-inhabiting gall crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Cryptochiridae). Acta Zoologica Stockholm 97(1): 117–126.

Verrill A. E. (1867). Remarkable instances of crustacean parasitism. American Journal of Science, 44(2), 126.

Warner G. F. (1967). The life history of the mangrove tree crab, Aratus pisoni. Journal of Zoology, 153, 321–335.

Warner, G.F., 1977. The biology of crustacea. Elek science London.

Watson J. (1970). Maturity, mating and egg laying in the spider crab, Chionoecetes opilio. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 27, 1607–1616.

Wear R. G. (1974). Incubation in British decapod Crustacea, and the effects of temperature on the rate and success of embryonic development. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 54, 745–762.

Wei T. P., Hwang J. S., Tsai M. L., & Fang L. S. (2006). New records of gall crabs (Decapoda, Cryptochiridae) from Orchid Island, Taiwan, northwestern Pacific. Crustaceana, 78(9), 1063–1077.

Wolodarsky Z., & Loya Y. (1980). Population dynamics of Trapezia crabs inhabiting the coral Styllophora pistillata in the north Gulf of Aqaba (abstract). Israel Journal of Zoology, 29, 204–205.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply thankful to Environmental Egyptian Affairs Agency members, the Red Sea Protectorates Sector, and members of the Zoology Department, Al-Azhar University, Nasr City, Cairo, Egypt, for unlimited support.

Funding

No funding.

Authors’ contributions

KAE is the main investigator responsible for the points of research and revision of the manuscript. ESS is the principle investigator of the research work, who is responsible for the field study, lab work, and writing the manuscript. MMAF is the main investigator who participated in the lab work and the writing and revision of the manuscript. MAMMA is the main investigator responsible for the field study, identification of specimens, and writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Damhougy, K.A., Salem, ES.S., Fouda, M.M.A. et al. The growth and reproductive biology of the coral gall crab, Hapalocarcinus marsupialis Stimpson, 1859 (Crustacea: Cryptochiridae), from the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, Egypt. JoBAZ 78, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-017-0002-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-017-0002-6