Abstract

Background

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), a primary symptom of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), negatively affects functioning and quality of life (QoL). EDS can persist despite primary airway therapy, and often remains unmanaged, potentially due to inadequate provider-patient communication. Ethnographic research was conducted to assess provider-patient communication about EDS.

Methods

Participating physicians (primary care n = 5; pulmonologists n = 5; sleep specialists n = 3) identified adult patients (n = 33) diagnosed with OSA who were prescribed positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy ≥6 months prior and previously reported EDS. Visits and post-visit interviews were video-recorded and analyzed using standardized, validated sociolinguistic techniques.

Results

Despite 55% of patients (18/33) reporting QoL impacts post-visit, this was discussed during 28% (5/18) of visits. Epworth Sleepiness Scale was administered during 27% (9/33) of visits. Many patients (58% [19/33]) attributed EDS to factors other than OSA. Physicians provided EDS education during 24% of visits (8/33). Prior to the visit, 30% (10/33) of patients were prescribed EDS medication, of which 70% (7/10) reported currently experiencing EDS symptoms.

Conclusions

EDS was minimally discussed and rarely reassessed or treated after PAP therapy initiation in this study. Patients often attributed EDS to factors other than OSA. The findings suggest physicians and patients may benefit from dialogue tools, routine use of screening tools, and patient education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), defined as an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5 with associated signs/symptoms, or an AHI ≥ 15 with no associated signs/symptoms, occurs on average in 22% (range, 9–37%) of men and 17% (range, 4–50%) of women (Sateia 2014; Franklin and Lindberg 2015). Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is a main symptom of OSA, and is often a primary complaint for patients seeking medical care (Pagel 2009; Dongol and Williams 2016). EDS linked to OSA is associated with a negative impact on patient and public safety (Ward et al. 2013; Lloberes et al. 2000), daily functioning and work productivity (Mulgrew et al. 2007; Omachi et al. 2009), and quality of life (QoL) (Silva et al. 2009). It is also associated with impairments in motivation and mood, including depression and anxiety (Bixler et al. 2005; Gasa et al. 2013; Pepin et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2015), and cognitive function including attention, memory, and higher-order executive functions (Dean et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2016; Redline et al. 1997; Werli et al. 2016).

Positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy is the standard of care to treat OSA (Epstein et al. 2009; Calik 2016), but 9–22% of patients with OSA experience persistent EDS despite adherence to PAP treatment and AHI normalization (Dongol and Williams 2016; Gasa et al. 2013; Pepin et al. 2009; Weaver et al. 2007; Weaver et al. 2004; Antic et al. 2011; Koutsourelakis et al. 2009; Weaver et al. 2005). There are many potential causes of EDS in patients with OSA, including insufficient sleep, PAP issues (eg, insufficient use, mask leaks), depression, anxiety, hypothyroidism, medication side effects, obesity, and other sleep disorders (Javaheri and Javaheri 2020). While there are effective therapies for EDS in OSA patients, such as modafinil, armodafinil, and solriamfetol, (Chapman et al. 2016; Sukhal et al. 2015; Pack et al. 2001; Rosenberg and Doghramji 2009; Schweitzer et al. 2019) many patients remain symptomatic (Gasa et al. 2013; Pepin et al. 2009). One reason may be that physician-patient dialogue about EDS is limited in OSA patients due to lack of practical objective EDS assessment tools (Chapman et al. 2016; Roth et al. 2010; Reuveni et al. 2004; Chervin et al. 1997), prioritization of PAP adherence (Sukhal et al. 2015; Pack et al. 2001; Pollak 2003), or patient under-recognition and minimization of EDS (Weaver et al. 2004; Engleman et al. 1997).

Fostering more effective communication has been shown to improve health outcomes, physician-patient alignment, and patient understanding and satisfaction (Hahn et al. 2008; Ong et al. 1995). To understand physician-patient communication regarding persistent EDS and its potential role in treatment decisions, we conducted an in-office ethnographic sociolinguistic study of visits.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

Primary care physicians (PCPs), pulmonologists, and sleep specialists (n = 5073) in community-based practices and nonacademic sleep centers across the United States were invited to participate in the study. Physicians who were board-certified or board-eligible in their specialty, in practice 2–35 years, and in practice full time, spent a minimum of 75% of time in direct patient care, conducted ≥75% of patient discussions in English and, in a typical month, treated ≥30 patients with OSA who had been prescribed PAP therapy, either continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) for ≥6 months, were eligible to participate.

Participating physicians identified eligible adult patients who were previously diagnosed with OSA, fluent in English, not cognitively impaired, and prescribed PAP therapy for ≥6 months prior to the visit and had reported experiencing EDS symptoms to their physician prior to the visit. Patients eligible for enrollment had a significant discussion of OSA during the visit. Participating patients identified eligible care partners who were people with whom they discussed treatment and/or who assisted in making treatment decisions.

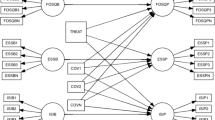

Study design

This study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (IRB Number: 120170306, Protocol Number: 1233110) and conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. All recorded participants provided written informed consent. The study methodology is summarized in Fig. 1. This study design emulates other ethnographic studies, such as Rubin et al. (2017).

One to 2 days of research was conducted at each physician’s practice by 1 member of a team of trained ethnographic researchers. Patients who met the criteria were invited by office staff to participate in this research upon arrival for their regularly scheduled appointments. Potential patient participants met with the researcher to receive information about the study and provide written informed consent. Participants were informed that they would be part of a communication study and their visits would be audio- and video-recorded. Specific research objectives were not shared with participating physicians, patients, care partners, or research coordinators.

Eligible care partners were invited to participate. Those who were interested in participating and present at the visit provided written informed consent. Patients with a care partner who was not at the visit were provided materials about the research to share with them. These care partners were given the opportunity to participate in a telephone interview (see Additional file 1). Written informed consent was acquired prior to the interview.

Physician-patient interactions were audio- and video-recorded without the researcher present in the exam room. Immediately following each visit, the researcher conducted an interview with the patient (approximate duration, 20 min) (see Additional file 2) and administered a written questionnaire (see Additional file 3). At the end of the day, the researcher conducted an interview with the physician about each patient (approximately 20 min per patient) and his or her general attitudes and treatment practices (10–20 min) (see Additional file 4). The physician was administered written questionnaires about each patient (see Additional file 5). The physician was able to reference patient records; the researcher was not provided access. The physician interviews and questionnaires were completed at the end of the day to minimize disruption of the office environment and typical practices. The interviews and questionnaires were used to gather history, demographics, attitudes, experiences, perceptions about the interaction, and alignment. Participating physicians, patients, care partners, and research coordinators were financially compensated for their participation. Due to the observational nature of this study, data collection only included observing physician and patient interactions and interviews/questionnaires to gather history, demographics, attitudes, experiences, perceptions about the interaction, and alignment. Clinical data on ESS scores, OSA severity, and primary therapy adherence were not collected.

Data analysis

Audio recordings of visits and interviews were transcribed. Video recordings were used as quality control and to reveal nonverbal communication. Transcripts were analyzed using interactional sociolinguistic methods to understand the conversational dynamics of the physician-patient interaction (Gumperz 1999; Hamilton 2004), including detailed analysis and categorization of language at the topic and word level and assessment of speaker roles and alignment. Adherence to PAP therapy was collected through patient and physician reports, rather than clinical measure, to assess alignment. A subset of transcripts was reviewed first to identify trends and develop hypotheses. An analytic plan was developed and executed on the full dataset. A Fisher’s exact test was conducted to test for statistical significance comparing proportions from different populations.

Themes were assessed using descriptive statistics, including:

-

The number of patients who reported EDS symptoms post-visit, reported EDS symptoms during the visit, related EDS symptoms to other factors, reported current QoL impacts of EDS, and/or had been prescribed medication for EDS prior to the visit

-

The number of visits when the following were discussed: QoL impacts of EDS, PAP therapy adherence and usage data, and/or adherence to medication for EDS

-

The number of visits at which physicians asked at least 1 open-ended question related to EDS, asked about QoL impacts of EDS, mentioned treatment options for EDS, and/or prescribed new treatment for EDS

-

The number of visits at which physicians and/or their office staff provided education about EDS and/or used the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) questionnaire

-

The percentage of the visit discussion focused on key topics, including EDS and PAP therapy

Results

Sample profile

A total of 19 (0.004%) physicians responded; 13 (0.003%) physicians located across the United States met the criteria and agreed to participate. PCPs (n = 5), pulmonologists (n = 5), and sleep specialists (n = 3) were enrolled.

A total of 39 patients were approached, consented, and recorded. Some of these patients did not meet the eligibility requirements because they were not prescribed PAP therapy for ≥6 months prior to the visit (n = 3), or there was minimal discussion of OSA during the visit (n = 3). A total of 33 patients were enrolled in the study. Forty-two percent (n = 14/33) of enrolled patients were seen by their pulmonologist, 33% (n = 11/33) by their PCP, and 24% (n = 8/33) by their sleep specialist.

Twelve care partners were also enrolled, of whom 7 participated in follow-up telephone interviews, 4 were present during the visit and interviewed at the office, and 1 was not present during the visit, but was interviewed at the office. Care partner interviews were not analyzed for this study. The characteristics of the physicians and patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Dialogue characteristics

The average visit length was 14.05 min (SD, ± 5.85). The average percentage of the visit discussion dedicated to key topics is illustrated in Fig. 2. Thirteen percent of the visit dialogue time (mean [SD] 1.83 min [± 1.77]) was related to EDS, including discussion within and outside the context of PAP therapy. EDS was discussed exclusively within the context of PAP therapy during 18% of visits (n = 6/33), of which 67% (n = 4/6) were with PCPs and 33% (n = 2/6) were with pulmonologists. Examples of this and other key characteristics of physician and patient visit dialogue are shown in Table 3.

Average percentage of visit discussion dedicated to key topics. Notes: Visit discussion among all participants, including physicians, patients, visit companions, and other healthcare professionals, if applicable. PAP Therapy: Discussion of PAP therapy (eg, Physician: “And how do you feel like you’re doing with your [CPAP] machine?”); PAP Therapy Treating EDS: Discussion of PAP therapy in the context of treating EDS (eg, Physician: “Did the use of the [CPAP] machine make you feel better during the day? Did you have more energy? Were you less sleepy?”); EDS: Discussion of EDS (eg, Physician: “There are medications to help during the daytime if you’re really sleepy.”); other OSA-related topics: Discussion of other OSA-related topics, such as sleep hygiene, weight, and other symptoms (eg, Physician: “I wouldn’t try to nap all over the house. I mean, obviously the bedroom is the place for sleeping.”); topics not related to OSA: Discussion of other topics during the visit that are not directly related to OSA (eg, Patient: “I’m allergic to penicillin.”). Abbreviations: EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PAP, positive airway pressure

During 24% (n = 8/33) of visits, physicians provided some education related to EDS, including information about symptoms, ESS scoring, potential impacts, and/or treatment. During visits with 33% (n = 11/33) of patients, physicians asked at least 1 open-ended question related to EDS. Of these patients, 45% were attending visits with their sleep specialist (n = 5/11; 5/8 sleep specialist visits), 36% with their pulmonologist (n = 4/11; 4/14 pulmonologist visits), and 18% with their PCP (n = 2/11; 2/11 PCP visits).

Screening and QoL impact

The ESS was administered during 27% of visits (n = 9/33). It was administered during 50% (n = 7/14) of pulmonology visits and 25% (n = 2/8) of sleep specialist visits. Among the visits that obtained an ESS (n = 9), physicians discussed the results with their patients 67% of the time (n = 6/9). During a third (n = 2/6) of these discussions, physicians segued from dialogue about ESS scores to dialogue about medication for EDS.

Physicians asked 18% (n = 6/33) of patients about the potential impact of EDS on QoL, despite 55% (n = 18/33) of patients reporting current QoL impacts of EDS at their post-visit.

Symptoms and treatment

PAP therapy adherence was discussed during all visits. It was augmented by discussion of PAP usage data during 42% (n = 14/33) of visits (57% [n = 8/14] with pulmonologists and 43% [n = 6/14] with sleep specialists).

Prior to the visit, 30% (n = 10/33) of patients had already been prescribed medication for EDS (4 of whom attended visits with sleep specialists, 4 with pulmonologists, and 2 with PCPs) (Fig. 3). Adherence to medication was discussed during all of these patients’ visits. Seventy percent (n = 7/10) of the patients prescribed medication were asked open-ended questions related to EDS versus 17% (n = 4/23) of patients who were not prescribed medication (P < 0.01). During visits, 70% of the patients prescribed medication (n = 7/10) reported currently experiencing EDS symptoms.

Among patients not prescribed medication, 78% (n = 18/23) were currently experiencing symptoms of daytime sleepiness and/or the need to nap during the day, as reported by the patient during the visit and/or post-visit interview. The vast majority (83%; n = 15/18) of these patients reported these EDS symptoms during the visit. However, treatment options for EDS were discussed in only 27% (n = 4/15) of cases and led to only one intervention from a sleep specialist for an oral appliance to specifically address EDS symptoms (Fig. 3).

Fifty-eight percent of patients (n = 19/33) associated their EDS symptoms to factors other than OSA, such as comorbidities, other treatments and medications, work, retirement, age, weight, and sleep habits.

Discussion

Although EDS is a core symptom of OSA and often the impetus for sleep evaluation (Pagel 2009; Dongol and Williams 2016), in this cross-sectional, observational study, EDS was minimally discussed and rarely reassessed or treated after PAP therapy initiation, even when patients were still experiencing EDS symptoms and related QoL impacts. The focus of the visit discussion in this study was on the use of PAP therapy, rather than clinical effectiveness and persistent symptoms. Ongoing assessment of EDS at regular intervals is recommended (Weaver et al. 2007); however, despite this recommendation, the ESS was not universally administered at physician visits in this study and patients were rarely asked at these visits about the impact EDS may have on their QoL. From a patient perspective, despite reporting persistent EDS, many patients attributed it to factors other than OSA, and did not bring up the QoL impacts with their physicians during the visits in this study.

Prior to this study, very little was known about communication between patients and treating physicians regarding EDS associated with OSA. This study was the first to explore the nature of this dialogue, using interactional sociolinguistic methods that are standard for this type of observational research, and identify areas for improvement. Studies of physician-patient communication in other disease categories have found that more effective communication, such as the increased use of open-ended questions, has led to improvement in health outcomes, physician-patient alignment, and patient understanding and satisfaction (Ong et al. 1995; Gumperz 1999). EDS is an important target for intervention in patients with OSA because it is associated with significant negative impacts on patient and public safety (Ward et al. 2013; Lloberes et al. 2000), patient daily functioning, work productivity, and QoL (Mulgrew et al. 2007; Omachi et al. 2009; Silva et al. 2009; Bixler et al. 2005; Gasa et al. 2013).

There are parallels between these findings and research in other fields in which routine screening for specific behavioral and mental health issues, such as diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol use, drug use, stress, depression, and anxiety have been shown to improve patient care and satisfaction (Krist et al. 2016; Sharp and Lipsky 2002). Other areas for which standard guidelines are lacking, including pain, domestic abuse, social neglect, and elder abuse, have seen substantial research and interest in developing screening guidelines (Owen et al. 2018; Shavers 2013; Ferreira et al. 2015; Sheehan et al. 2016; Wagenaar et al. 2010), suggesting that routine screening is increasingly recognized as a valuable approach to improve care across a wide range of settings. Thus, an approach may be to include screening for EDS during routine medical evaluation for all patients, even those not diagnosed with OSA. This approach may identify other causes of EDS, including narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, severe social jet lag, and chronic partial sleep deprivation (Pagel 2009; Lunn et al. 2017). The ESS is a useful tool in clinical practice to evaluate EDS, however, it may not be representative of how patients universally describe and experience their EDS. Using this tool with effective open-ended questioning, or developing a new screening and monitoring tool for EDS in OSA that is more representative of the way current patients speak to their sleepiness, could help optimize the treatment of EDS in OSA (Omobomi and Quan 2018).

This study had some limitations. The participation fraction was small, which was expected due to the observational nature of the research, thus generalization was limited, and the study was not powered to compare specialists and generalists. The rate of response and sample size, including the study of specialty cohorts, were typical of ethnographic sociolinguistic research (Hahn et al. 2008; Rubin et al. 2017; Gumperz 1999; Hamilton 2004). Participants in this research knew they were being recorded; this, along with the level of trust the participant had previously established with the provider, may have affected their behavior. One could postulate that this may have caused participants to communicate more effectively than would be typical, so it is unclear why those who participated would have been unlikely to address EDS. Due to the cross-sectional and observational nature of this study, causal associations, including why EDS was not addressed, could not be determined. Since the majority of patients had been visiting these physicians for years, it is possible that EDS may have been discussed more comprehensively during previous visits, but the single-day design of this study prohibited characterization of the longitudinal relationship between the physician and patient. If this was the case, it could also suggest the need to reevaluate EDS symptoms in patients who may have initially reported resolution of EDS, since many of these patients described EDS symptoms at the time of this study.

Due to the nature of this study, another limitation includes the lack of collection of clinical data on PAP usage, OSA severity, or subjective or objective measures of EDS (eg, Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores, Maintenance of Wakefulness Test mean sleep latency, or Multiple Sleep Latency Test mean sleep latency). It is acknowledged that many clinical factors shape the discussion between patient and physician, and these clinical data may have informed why EDS was not discussed.

This study did not explore possible reasons why EDS is not addressed after PAP therapy initiation (“attitudes to EDS”), including de-prioritization of EDS, and assumption that patients would raise the topic if it is of concern. This research also did not assess why patients attribute persistent EDS to factors other than OSA. However, this research may inform the design of future studies to explore potential areas for intervention.

Conclusions

In this ethnographic sociolinguistic study, during visits between physicians and sleepy patients with OSA treated with PAP therapy, EDS had a minimal role in the dialogue. Symptoms and QoL impacts were often overlooked, and treatment options were rarely discussed or prescribed. Physicians and patients may benefit from improved use of existing screening and monitoring tools for EDS (eg, ESS) and access to dialogue tools (eg, discussion guides) and communication training (eg, to ask open-ended questions). One approach to improved communication about EDS would be to include standardized assessment and research-guided questioning during routine medical evaluation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AHI:

-

Apnea-Hypopnea Index

- BiPAP:

-

Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure

- CPAP:

-

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- EDS:

-

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- PAP:

-

Positive Airway Pressure

- PCP:

-

Primary Care Physicians

- OSA:

-

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

References

Antic NA, Catcheside P, Buchan C, Hensley M, Naughton MT, Rowland S, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34(1):111–9.

Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Calhoun SL, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Excessive daytime sleepiness in a general population sample: the role of sleep apnea, age, obesity, diabetes, and depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4510–5.

Calik MW. Treatments for obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2016;23(4):181–92.

Chapman JL, Serinel Y, Marshall NS, Grunstein RR. Residual daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea after continuous positive airway pressure optimization: causes and management. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11(3):353–63.

Chervin RD, Aldrich MS, Pickett R, Guilleminault C. Comparison of the results of the Epworth sleepiness scale and the multiple sleep latency test. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(2):145–55.

Dean B, Aguilar D, Shapiro C, Orr WC, Isserman JA, Calimlim B, et al. Impaired health status, daily functioning, and work productivity in adults with excessive sleepiness. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(2):144–9.

Dongol EM, Williams AJ. Residual excessive sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea on treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22(6):589–94.

Engleman HM, Hirst WS, Douglas NJ. Under reporting of sleepiness and driving impairment in patients with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. J Sleep Res. 1997;6(4):272–5.

Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–76.

Ferreira M, dos Santos CL, Vieira DN. Detection and intervention strategies by primary health care professionals in suspected elder abuse. Acta Medica Port. 2015;28(6):687–94.

Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(8):1311–22.

Gasa M, Tamisier R, Launois SH, Sapene M, Martin F, Stach B, et al. Residual sleepiness in sleep apnea patients treated by continuous positive airway pressure. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(4):389–97.

Gumperz JJ. On interactional sociolinguistic method. In: Sarangi S, Roberts C, editors. Talk, work and institutional order: discourse in medical, mediation and management settings. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 1999. p. 453–72.

Hahn SR, Lipton RB, Sheftell FD, Cady RK, Eagan CA, Simons SE, et al. Healthcare provider-patient communication and migraine assessment: results of the American migraine communication study, phase II. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(6):1711–8.

Hamilton HE. Symptoms and signs in particular: the influence of the medical concern on the shape of physician-patient talk. Commun Med. 2004;1(1):59–70.

Javaheri S, Javaheri S. Update on persistent excessive daytime sleepiness in OSA. Chest. 2020;158(2):776–86.

Koutsourelakis I, Perraki E, Economou NT, Dimitrokalli P, Vagiakis E, Roussos C, et al. Predictors of residual sleepiness in adequately treated obstructive sleep apnoea patients. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):687–93.

Krist AH, Glasgow RE, Heurtin-Roberts S, Sabo RT, Roby DH, Gorin SN, et al. The impact of behavioral and mental health risk assessments on goal setting in primary care. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(2):212–9.

Lee SA, Han SH, Ryu HU. Anxiety and its relationship to quality of life independent of depression in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(1):32–6.

Lloberes P, Levy G, Descals C, Sampol G, Roca A, Sagales T, et al. Self-reported sleepiness while driving as a risk factor for traffic accidents in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and in non-apnoeic snorers. Respir Med. 2000;94(10):971–6.

Lunn RM, Blask DE, Coogan AN, Figueiro MG, Gorman MR, Hall JE, et al. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: a report on the National Toxicology Program's workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Sci Total Environ. 2017;607-608:1073–84.

Mulgrew AT, Ryan CF, Fleetham JA, Cheema R, Fox N, Koehoorn M, et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness on work limitation. Sleep Med. 2007;9(1):42–53.

Omachi TA, Claman DM, Blanc PD, Eisner MD. Obstructive sleep apnea: a risk factor for work disability. Sleep. 2009;32(6):791–8.

Omobomi O, Quan SF. A requiem for the clinical use of the Epworth sleepiness scale. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):711–2.

Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–18.

Owen GT, Bruel BM, Schade CM, Eckmann MS, Hustak EC, Engle MP. Evidence-based pain medicine for primary care physicians. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31(1):37–47.

Pack AI, Black JE, Schwartz JR, Matheson JK. Modafinil as adjunct therapy for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(9):1675–81.

Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391–6.

Pepin JL, Viot-Blanc V, Escourrou P, Racineux JL, Sapene M, Levy P, et al. Prevalence of residual excessive sleepiness in CPAP-treated sleep apnoea patients: the French multicentre study. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1062–7.

Pollak CP. Con: modafinil has no role in management of sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):106–7 discussion 7–8.

Redline S, Strauss ME, Adams N, Winters M, Roebuck T, Spry K, et al. Neuropsychological function in mild sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 1997;20(2):160–7.

Reuveni H, Tarasiuk A, Wainstock T, Ziv A, Elhayany A, Tal A. Awareness level of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome during routine unstructured interviews of a standardized patient by primary care physicians. Sleep. 2004;27(8):1518–25.

Rosenberg R, Doghramji P. Optimal treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and excessive sleepiness. Adv Ther. 2009;26(3):295–312.

Roth T, Bogan RK, Culpepper L, Doghramji K, Doghramji P, Drake C, et al. Excessive sleepiness: under-recognized and essential marker for sleep/wake disorder management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(Suppl 2):S3–24 quiz S5–7.

Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Martino S, Hewett KA, Panés J. Communication between physicians and patients with ulcerative colitis: reflections and insights from a qualitative study of in-office patient-physician visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(4):494–501.

Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014;146(5):1387–94.

Schweitzer PK, Rosenberg R, Zammit GK, Gotfried M, Chen D, Carter LP, et al. Solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea (TONES 3): a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1421–31.

Sharp LK, Lipsky MS. Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(6):1001–8.

Shavers CA. Intimate partner violence: a guide for primary care providers. Nurse Pract. 2013;38(12):39–46.

Sheehan OC, Ritchie CS, Fathi R, Garrigues SK, Saliba D, Leff B. Development of quality indicators to address abuse and neglect in home-based primary care and palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2577–84.

Silva GE, An MW, Goodwin JL, Shahar E, Redline S, Resnick H, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep symptoms with change in quality of life: the sleep heart health study (SHHS). Sleep. 2009;32(8):1049–57.

Sukhal S, Khalid M, Tulaimat A. Effect of wakefulness-promoting agents on sleepiness in patients with sleep apnea treated with CPAP: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(10):1179–86.

Wagenaar DB, Rosenbaum R, Page C, Herman S. Primary care physicians and elder abuse: current attitudes and practices. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(12):703–11.

Ward KL, Hillman DR, James A, Bremner AP, Simpson L, Cooper MN, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness increases the risk of motor vehicle crash in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(10):1013–21.

Weaver EM, Kapur V, Yueh B. Polysomnography vs self-reported measures in patients with sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(4):453–8.

Weaver EM, Woodson BT, Steward DL. Polysomnography indexes are discordant with quality of life, symptoms, and reaction times in sleep apnea patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(2):255–62.

Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, Bloxham T, George CF, Greenberg H, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30(6):711–9.

Werli KS, Otuyama LJ, Bertolucci PH, Rizzi CF, Guilleminault C, Tufik S, et al. Neurocognitive function in patients with residual excessive sleepiness from obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective, controlled study. Sleep Med. 2016;26:6–11.

Zhou J, Camacho M, Tang X, Kushida CA. A review of neurocognitive function and obstructive sleep apnea with or without daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med. 2016;23:99–108.

Acknowledgements

Work for this study was performed at Ogilvy Health, Parsippany, New Jersey. The authors thank the research team at Ogilvy Health for research support, including significant contributions from Ashli Sherman, BA, Tara Shannon, BS, and Lauren Johnson, MA. The authors thank Ashli Sherman, BA, and Tabytha Gil, MA, of Ogilvy Health for providing medical writing and editorial support, which was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). The authors also thank all participating physicians, patients, and care partners for their participation in this research.

Funding

This research was sponsored by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Role of the sponsor: The sponsor authors had a role in the design of the study and had no role in the acquisition and analysis of the data. Although Jazz Pharmaceuticals was involved in the review of the manuscript, the content of this manuscript, the ultimate interpretation, and the decision to submit it for publication was made by the authors independently.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KAH was the principal investigator for the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. CW, RKB, KD, JO, SB, DLH, KAH, and RT contributed to the conception and design of the study, data interpretation, drafting of the submitted article, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. KAH contributed to data acquisition and analysis. CW, RKB, KD, JO, SB, DLH, KAH, and RT provided final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors have reviewed and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (IRB Number: 120170306, Protocol Number: 1233110) and conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. All recorded participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CW and KD are consultants for, and participate in research that is supported by, Jazz Pharmaceuticals. RKB is on the speakers’ bureau for Jazz Pharmaceuticals, advisory board and has participated in industry-sponsored research. JO is an employee of the Caduceus Corporation and the Clayton Sleep Institute, LLC; has received research funding from Fisher-Paykel, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Respironics, and Teva; has served on the speakers’ bureaus for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, and Teva; and serves as a board member for the National Sleep Foundation. SB and DLH are former employees of Jazz Pharmaceuticals who, in the course of their employment, have received stock options exercisable for, and other stock awards of, ordinary shares of Jazz Pharmaceuticals PLC. KAH is an employee of Ogilvy Health and was a paid consultant to Jazz Pharmaceuticals in connection with performing this research and with the development of this publication. RT receives royalty payments from MyCardio, LLC for CG-based sleep and sleep apnea phenotyping software, has consulted for DeVilbiss-Drive for CPAP software development, and is a consultant for GLG Councils and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. He has a patent for a device regulating CO2 for central/complex apnea treatment.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shay Bujanover and Danielle L Hyman are former employees of Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Care Partner Post-Visit Interview Discussion Guide.

Additional file 2.

Patient Post-Visit Interview Discussion Guide.

Additional file 3.

Patient Post-Visit Interview Questionnaire.

Additional file 4.

Physician Post-Visit Interview Discussion Guide.

Additional file 5.

Physician Post-Visit Interview Questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Won, C., Bogan, R.K., Doghramji, K. et al. In-office communication about excessive daytime sleepiness associated with treated obstructive sleep apnea: insights from an ethnographic study of physician-patient visits. Sleep Science Practice 6, 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-022-00072-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-022-00072-y