Abstract

Background

Sleep hygiene is a series of behavioral practices that can be performed by individuals with sleep complaints to prevent or reverse sleep difficulties. The feasibility, cost-effectiveness, absence of side effects and immediate responses to sleep problems make sleep hygiene practices more applicable than other treatment options for people living with HIV/AIDS. However, there is no evidence regarding sleep hygiene awareness and its practice in people with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the knowledge, practice and correlates of sleep hygiene among adults attending outpatient anti-retroviral treatment at Zewditu Memorial Hospital.

Methods

This was an institutional based cross-sectional study conducted from 1st of May to 16th of June 2018 amongst people attending anti-retroviral therapy follow-up at Zewditu Memorial Hospital. Systematic random sampling technique was used to recruit a total of 396 study participants. Data were collected using interviewer-administered questionnaire. The Sleep Hygiene Index was used to measure the level of sleep hygiene of study participants. Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with sleep hygiene practice. In the multi-variable analysis, variables with P-values of less than 0.05 were considered as significant correlates of sleep hygiene practice with 95% confidence interval.

Results

The findings of this study showed that there are limitations regarding the knowledge and practice of sleep hygiene of people with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. None of the participants attended training regarding sleep hygiene. More than half (51.3%) had poor sleep hygiene practice. Female sex [AOR = 5.80:95% CI (3.12, 10.7)], being single [AOR =2.29:95% CI (0.13, 9.51)], depression [AOR = 2.93: 95% CI (1.73, 4.96)] and current khat use [AOR = 3.30; 95% CI (1.67, 6.50)] were identified as statistically significant correlates of poor sleep hygiene practice.

Conclusions

Knowledge regarding sleep hygiene is poor, and its practices are incorrect amongst people living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. These findings demonstrate a need for professionals to play a major role in addressing this problem by integrating sleep hygiene as an added treatment modality to the HIV/AIDS care service. Designing training programs and awareness creation strategies for people with HIV/AIDS to improve their sleep hygiene practice is also highly recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sleep occupies one third of the human beings’ life span and good quality of sleep is essential to enable people to have good physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being and better quality of life in general (Sharpley, 1985; Association AP, 2013). However, sleep deprivation causes negative consequences such as physical weakness, reduced cognitive performance (for example, problems solving tasks), emotional disturbances and increases vulnerability to other psychological and physiological disturbances (Association AP, 2013; Johnston et al., 2017).

Sleep disturbance is a more prevalent complaint amongst people with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) than the general population (Azagew et al., 2017). Current literature reports that 40 to 70% of people with HIV have a significant sleep disturbance commonly characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation, awakenings during the night, early morning awakenings, reduced sleep time and daytime sleepiness (Taibi, 2013; Reid & Dwyer, 2005; Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998a). Difficulties in coping with their sero-positive status (Junqueira et al., 2008a), acquired AIDS related stigma, functional impairments (McGrath & Reid, 2008), the direct brain effects of the HIV-virus and opportunistic infections (Owens & Hicks, 2018), substance abuse and side effects of antiretroviral therapy (ART) medications (Taibi et al., 2013) are some of the likely reasons accounted for the sleep disturbances of people with HIV/AIDS (Oshinaike et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2006).

Sleep disturbances can also reduce adherence with ART drugs, viral load suppression and immunity and increases the risks of opportunistic infections which may further result in poor treatment outcome, more functional impairments, poor quality of life, and increased risk of accidents due to daytime sleepiness (Byun et al., 2016; Saberi et al., 2011; Babson et al., 2013). Sleep dysfunction may also contribute to the use of illegal psycho active substances for their depressant and sedative effects (Calkins et al., 2013).

Although there are drugs used to improve sleep disturbances efficiently, they may have several effects such as tolerance, increased pill burden, adverse reaction, drug dependency and higher health care costs (Fismer & Pilkington, 2012; Hu et al., 2015). As a result, it has become clinically important to design appropriate interventions focusing on behavioral changes with minimal or no complications to improve and promote sleep hygiene practices among people with HIV/AIDS (Hu et al., 2015; Webel et al., 2013). Thus, non-pharmacological interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy, life style modification and sleep hygiene practices are currently being used to manage poor quality of sleep (Takeda et al., 2017).

Sleep hygiene is a series of behavioral practices that can be performed by individuals at their home to improve their sleep quality (Santos et al., 2018). Sleep hygiene has been found to have more positive effects on the sleep quality of people with HIV/AIDS (Santos et al., 2018). Although there are different non-pharmacological interventions (for example, cognitive behavioral therapy) that have been shown to be more effective than sleep hygiene in resolving insomnia, the feasibility, cost-effectiveness, absence of side effects and the potential for immediate response to sleep problems make this treatment option more applicable for people with HIV/AIDS in resource limited areas financial limitations and lack of access to health care services (Gamaldo et al., 1999; Webel & Higgins, 2012). However, the practice of sleep hygiene of people depends in part on these individuals knowledge and perception regarding sleep physiology and its clinical importance (Gamaldo et al., 1999). As a result, professionals are expected to play a major role in the assessment and promotion of sleep hygiene practice among people with HIV/AIDS (Webel & Higgins, 2012).

Despite the feasibility and overall clinical importance of sleep hygiene, it is under-recognized, and largely ignored by professionals working with ART centers (Jean-Louis et al., 2012; Phillips et al., 2005). As per the authors’ knowledge, there are no other previous studies conducted in Ethiopia regarding the knowledge and practice of sleep hygiene of people with HIV/AIDS. Therefore, assessment of sleep hygiene awareness and practice may have important clinical and policy implications by demonstrating the level of sleep hygiene practice in this region and may suggest possible strategies to improve sleep hygiene practices of people with HIV/AIDS. The findings of this study may provide important insight for future researches.

Methods

Study design and period

This was an institutional based cross-sectional study conducted from May 1st to June 16th, 2018.

Study area and participants

This study was conducted at Zewditu Memorial Hospital (ZMH) located in Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia). Currently, ZMH became the leading and largest hospital providing ART for about 17,857 HIV-positive individuals both in outpatient department and inpatient services. More than 7299 individuals are expected to be served with palliative care, HIV counseling and testing, sexually transmitted infections services and post-exposure prophylaxis services monthly.

Adults who had the ART clinic follow-up service at ZMH for at least 6 months were included. In the study, individuals less than 18 years old, with serious illness, limited commutation capabilities and those with less than 6 months of follow-up duration were excluded.

Sample size determination and sampling

The sample size required for this study was estimated using a single population proportion formula (\( \mathrm{n}=\frac{\mathrm{Z}{\frac{\upalpha}{2}}^2\mathrm{p}\left(1-\mathrm{p}\right)}{d2}\Big) \) with assumptions of standard normal distribution (Z = 1.96), 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% margin of error (d = 0.05) and P = 50% as there had been no studies conducted regarding sleep hygiene in Ethiopia for compression. Then, this yielded a sample size of 384. By considering a 10% non-response rate, the total sample size of this study was 423.

First, the number of people with HIV/AIDS expected visit the ART clinic during the data collection time was identified. Then, systematic random sampling was used to select study participants at a regular interval. The interval (K) was determined by dividing the total number of eligible individuals expected to visit the centre (2342) during the data collection period by the calculated sample size (K = 2342/423 = 5.5). The first participant was selected between one and five through lottery method. Finally, study participants were identified for every 5th intervals until the calculated sample size was addressed.

Data collection instruments and procedures

Data were collected using a pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire had different sub-sections including; socio-demographic characteristics, HIV/AIDS related stigma scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Oslo 3 items Social Support Scale (OSS-3) and Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI).

The outcome variable (sleep hygiene) was measured using the Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI). SHI is a 13-item self-reporting tool designed to assess the practice of sleep hygiene behaviors. The tool has shown adequate reliability and validity, moderate internal consistency and good 2-weeks of test-retest stability (r = 0.71, p < 0.001) (Cho et al., 2013). Each of the 13 items was rated on a five-point scale; 0 (never), 1 (rarely), 2 (sometimes), 3 (frequently) and 4 (always). The response of each item was measured and added together to get the total SHI sum score which ranges from 0 to 52. The higher score of SHI corresponds to the poorer sleep hygiene practice. Then, the total sum score was categorized as “good practice” and “poor practice” using the mean score of SHI as a cutoff point. Individuals with a total sum score of above and equal to the mean score (28.4) were considered as having poor sleep hygiene practice (Cho et al., 2013).

Explanatory variables were also measured using different standardized tools. Accordingly, the Ethiopian version of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to assess anxiety and depression. HADS is a validated tool used to measure anxiety and depression among people with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia with good reliability. In this study, HADS had an acceptable internal consistency between items as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 and 0.87 to measure anxiety and depression subscales, respectively. Individuals with a sum score of ≥8 from the total sum score (14) were considered as screened positive for anxiety and depression (Reda, 2011).

The 12-item HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale was used to measure the perceived HIV/AIDS related stigma among people with HIV/AIDS. Each of the 12 questions has a 4-point Liker scale, responses ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree), and has a total sum score ranging from 0 to 48 (Van Rie et al., 2008). In this study, participants who scored above or equal to the mean score (21.4) were considered as having HIV related stigma (Van Rie et al., 2008).

The Oslo-3 items Social Support Scale (OSS-3) was used to measure the perceived social support level of people with HIV/AIDS. The tool has three questions with a total sum scores ranging from 3 to 14. The higher sum score of the tool corresponds to the better social support level of individuals and vice versa. The sum score of OSS-3 was categorized as poor social support (3–8), moderate social support (9–11) and strong social support level (12–14) (Dalgard, 2009).

Socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, residency, educational level, occupational status and family structure) and HIV/AIDS related clinical factors were recorded from the clients’ medical charts in a confidential way. Clinical factors included in this study were years of follow up, WHO HIV/AIDS clinical stage, recent CD4 level, medication adherence, comorbid illness and types of ART regime.

The questionnaire was first prepared in English and translated to Amharic (the local language of the study area), and then back to English to check its consistency. Two days of training was delivered to data collectors (six clinical nurses) and supervisors (two mental health professionals) regarding the contents of the questionnaire and data collection procedures. Prior to the actual data collection, the local language version of the questionnaire was pretested at Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital ART clinic among 22 individuals (5% of the estimated sample size). Based on the pretest results, minor modification was done regarding the content of the questionnaire, and some statement were rewritten due to their vague expression and difficulties of being understood by participants.

Data processing and analysis

First, the collected data were checked for its completeness and consistency. The data were then entered to EPIDATA 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 20 (software) for analysis. We used binary logistic analysis to test the significant association of each independent variable with the outcome variable (sleep hygiene). Then, variables with P-values of less than 0.25 during binomial analysis were entered together to multivariate analysis to control possible cofounders. In the final model, a P-value of less 0.05 was used to consider variables as statistically significant predictors of poor sleep hygiene practice.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics of respondents

From a total of 423 study participants invited to take part in this study, 396 completed the interview properly with a response rate of 96.1%. The mean and standard deviation (+SD) age of the respondents was 38.57 (±10.76) years. The gender proportions of participants were almost equal and more than half, (69.7%) were Orthodox by their religion (Table 1).

Clinical and psycho-social characteristics

The majority of study participants, (74.2%) were at stage I of the WHO clinical HIV/AIDS categories, 55.3% had recent Cell Differentiation (CD4) counts greater than 200 cells/mm3 and 74.7% were on the first line regimen of ART drugs. Nearly half, (51.5%) were screened positive for depression and 49.0% had perceived stigma towards their HIV-positive sero-status. The finding of this study showed that the sleep disturbance is more common among HIV-infected individuals with poor sleep hygiene practice and people with good sleep hygiene practice had a better quality of sleep (Table 2).

Knowledge and practice of sleep hygiene

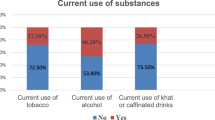

The majority of participants (76.7%) reported that they did not hear any previous information regarding sleep hygiene practice, and 25.3% received information related to sleep hygiene practice from media and other different sources. None of the participants attended any training related to sleep hygiene. A majority of participants, (89%) reported that they get out of bed at different times from day to day and 72.3% use caffeine within 4 h of going to bed or after going to bed. The mean (SD) score of SHI was 28.4 (4.72) among people with HIV/AIDS attending ART follow-up at Zewditu Memorial Hospital. More than half (51.3%) of participants had a SHI sum score of above or equal to the mean score and considered as having poor sleep hygiene practice with 95% CI (47.0, 55.6).

Predictors of sleep hygiene practice

In the multivariable analysis, female sex, being single, comorbod depression and current Khat chewing habit were found to have statistically significant correlation with poor sleep hygiene practice among people with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia (Table 3).

Discussion

Currently, sleep hygiene is recommended as one component of the various treatment modalities for people with sleep disturbances (Hughes, 2004). However, people with HIV/AIDS in various regions do not have adequete information regarding sleep hygiene and their understanding of sleep hygiene is generally poor (Hughes, 2004). Such information gaps may then impact the implementation of sleep hygiene practice (Byun et al., 2016).

However, the understanding and clinical implementations of sleep hygiene amongst people with HIV/AIDS is not well addressed in resource limited areas, including Ethiopia. Therefore, this study adds new knowledge regarding the understanding of people with HIV/AIDS towards sleep hygiene and its practical implementation. Moreover, this study recommended possible strategies to be implemented for sleep hygiene promotion in clinical populations, particularly people with HIV/AIDS.

The findings of this study showed that 76.7% of people with HIV/AIDS had no exposure to information related to sleep hygiene in their life time, and no participants attended trainings regarding sleep hygiene. As it relates to the prevalence of sleep hygiene practice, the majority (89%) of the studied individuals mentioned that they get out of bed at different times from day to day and 72.3% use caffeine within 4 h. of going to bed or after going to bed. Males had better sleep hygiene practice than females, and individuals with depressive symptoms had very poor sleep hygiene practice as compared to their counterparts.

The overall sleep hygiene practice was poor (51.3% [95% CI (47.0, 55.6)]) among people with HIV/AIDS attending outpatient ART follow-up in Ethiopia. The findings of this study has been supported by another study (Redman, n.d.). These medical clinics provide an opportunity for professionals to promote sleep hygiene practices for people with HIV/AIDS by integrating its service with of HIV/AIDS care (Huang et al., 2017). Psycho-social interventions focusing on the adaptation and best implementations of sleep hygiene is recommended as an applicable and cost effective medical assistance to people living with HIV/AIDS (Gamaldo et al., 1999).

This study also identified predictors of poor sleep hygiene practice of people living with HIV/AIDS. The multivariable analysis of this study showed that female sex, being single, comorbid depression and current Khat use habit had statistically significant association with poor sleep hygiene practice among people with HIV/AIDS. Accordingly, the odds of having poor sleep hygiene practice among females were increased by 5.8 times as compared to males. This finding is supported by other similar studies of Cameroon (Njoh et al., 2017) and Nigeria (Bisong, 2017). This might be explained by the fact that females are commonly homemakers in Ethiopia, and might be preoccupied with other activities in their home as compared to males (Lee et al., 2014). This may limit their ability to access educational opportunities and the ability to implement sleep hygiene practices (Junqueira et al., 2008a).

Being single increases the risk of having poor sleep hygiene practice by 3.2 times as compared to individuals who are married and living together. This finding is parallel with findings from a similar study conducted in Iran (Dabaghzadeh et al., 2013). A possible explanation for this significant association might be due to the fact that unmarried individuals often feel loneliness and lack social support which may provide a means to share their stressful situations when in crisis. Such feelings can exacerbate their quality of sleep and its hygienic practices (Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998b).

Individuals who screened positive for depression were 2.9 times more likely to have poor sleep hygiene practice as compared to their counterparts. This result is in line with other previous studies (Gutierrez et al., 2019; Junqueira et al., 2008b). This finding is possibly explained by diminished motivation and associated lack of energy in depressed individuals limiting their capabilities to perform sleep hygiene practice as diminished motivation and fatigue are common complains of people with this condition (Voinescu & Szentagotai-Tatar, 2015; Papadopoulos et al., 2019). Moreover, people with depressive symptoms commonly used addictive substances to escape from their stressful situation and such substances may cause individuals to become careless and forgetful in practicing sleep hygiene activities (Papadopoulos et al., 2019).

Finally, the finding of this study revealed that the odds of having poor sleep hygiene practice among people with a current Khat use habit were increased by 3.3 times as compared to individuals who did not use Khat. This is parallel to other study findings (Ramamoorthy et al., 2017; Manzar et al., 2017). The possible reason for this association might be due to the compulsive behavioral effects that this substance may cause which can diminish their commitment to perform sleep hygiene practices (Manzar et al., 2017). Moreover, people who use Khat commonly spend most of their time in searching for Khat to satiate their craving and may not have time nor interest to practice sleep hygiene behaviors (Berhanu & Mossie, 2018).

Limitations of the study

This study has limitations. First, the study was conducted among people living with HIV/AIDS that may not be representative to the general population in Ethiopia. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study design may not demonstrate accurately the cause and effect relationships between variables.

Conclusion

The finding of this study showed that there were limitations regarding knowledge of sleep hygiene and its practice was poor amongst people living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. This demonstrates a need for professionals to play a major role in addressing this problem by integrating sleep hygiene as an added treatment modality to the HIV/AIDS care service. Designing trainings and awareness creation strategies for people with HIV/AIDS to improve their knowledge and practice of sleep hygiene is also highly recommended.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data of this manuscript is available, and can be accessed from the corresponding author Zelalem Belayneh upon request with the email address of “zelalembe45@gmail.com”.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- AMSH:

-

Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odd Ratio

- ART:

-

Anti Retroviral Therapy

- CD4:

-

Cell Differentiation

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COR:

-

Crude Odd Ratio

- EPIDATA:

-

Epidemiological Data

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- OSS-3:

-

Oslo Three Social Support Scale

- PLWHA:

-

People Living with HIV/AIDS

- SHI:

-

Sleep Hygiene Index

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ZMH:

-

Zewditu Memorial Hospital

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

Azagew AW, Woreta HK, Tilahun AD, Anlay DZ. High prevalence of pain among adult HIV-infected patients at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2461.

Babson KA, Heinz AJ, Bonn-Miller MO. HIV medication adherence and HIV symptom severity: the roles of sleep quality and memory. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(10):544–52.

Berhanu H, Mossie A. Prevalence and associated factors of sleep quality among adults in Jimma Town, Southwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Sleep Disord. 2018;2018:8342328.

Bisong E. Predictors of sleep disorders among HIV out-patients in a tertiary hospital. Recent Adv Biol Med. 2017;3(2017):2747.

Byun E, Gay CL, Lee KA. Sleep, fatigue, and problems with cognitive function in adults living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(1):5–16.

Calkins AW, Hearon BA, Capozzoli MC, Otto MW. Psychosocial predictors of sleep dysfunction: the role of anxiety sensitivity, dysfunctional beliefs, and neuroticism. Behav Sleep Med. 2013;11(2):133–43.

Cho S, Kim G-S, Lee J-H. Psychometric evaluation of the sleep hygiene index: a sample of patients with chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):213.

Dabaghzadeh F, Khalili H, Ghaeli P, Alimadadi A. Sleep quality and its correlates in HIV positive patients who are candidates for initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Iran J Psychiatry. 2013;8(4):160.

Dalgard O. Social support-definition and scope: EUPHIX, EUphact. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2009.

Fismer KL, Pilkington K. Lavender and sleep: a systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Integr Med. 2012;4(4):e436–e47.

Gamaldo CE, Gamaldo A, Creighton J, Salas RE, Selnes OA, David PM, et al. Sleep and cognition in an HIV+ cohort: a multi-method approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;63:5.

Gutierrez J, Tedaldi EM, Armon C, Patel V, Hart R, Buchacz K. Sleep disturbances in HIV-infected patients associated with depression and high risk of obstructive sleep apnea. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119842268.

Hu RF, Jiang XY, Chen J, Zeng Z, Chen XY, Li Y, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for sleep promotion in the intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD008808.

Huang X, Li H, Meyers K, Xia W, Meng Z, Li C, et al. Burden of sleep disturbances and associated risk factors: a cross-sectional survey among HIV-infected persons on antiretroviral therapy across China. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3657.

Hughes A. Symptom management in HIV-infected patients. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2004;15(5):7S–13S.

Jean-Louis G, Weber KM, Aouizerat BE, Levine AM, Maki PM, Liu C, et al. Insomnia symptoms and HIV infection among participants in the Women's interagency HIV study. Sleep. 2012;35(1):131–7.

Johnston L, O'Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J, Patrick M, Miech R. HIV/AIDS: risk & protective behaviors among adults ages 21 to 40 in the US, 2004–2016; 2017.

Junqueira P, Bellucci S, Rossini S, Reimão R. Women living with HIV/AIDS: sleep impairment, anxiety and depression symptoms. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008a;66(4):817–20.

Junqueira P, Bellucci S, Rossini S, Reimao R. Women living with HIV/AIDS: sleep impairment, anxiety and depression symptoms. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008b;66(4):817–20.

Lee KA, Gay C, Humphreys J, Portillo CJ, Pullinger CR, Aouizerat BE. Telomere length is associated with sleep duration but not sleep quality in adults with human immunodeficiency virus. Sleep. 2014;37(1):157–66.

Manzar MD, Salahuddin M, Maru TT, Dadi TL, Abiche MG, Abateneh DD, et al. Sleep correlates of substance use in community-dwelling Ethiopian adults. Sleep Breath. 2017;21(4):1005–11.

McGrath L, Reid S. Sleep and Quality of Life in HIV and AIDS. In Sleep and Quality of Life in Clinical Medicine. Humana Press, 2008. p. 505-14.

Njoh AA, Mbong EN, Mbi VO, Mengnjo MK, Nfor LN, Ngarka L, et al. Likelihood of obstructive sleep apnea in people living with HIV in Cameroon–preliminary findings. Sleep Sci Pract. 2017;1(1):4.

Oshinaike O, Akinbami A, Ojelabi O, Dada A, Dosunmu A, Olabode SJ. Quality of sleep in an HIV population on antiretroviral therapy at an urban tertiary Centre in Lagos, Nigeria. Neurol Res Int. 2014;2014:298703.

Owens RL, Hicks CB. A wake-up call for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) providers: obstructive sleep apnea in people living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(3):472–6.

Papadopoulos D, Kiagia M, Charpidou A, Gkiozos I, Syrigos K. Psychological correlates of sleep quality in lung cancer patients under chemotherapy: a single-center cross-sectional study. Psychooncology. 2019;28(9):1879–86.

Phillips KD, Mock KS, Bopp CM, Dudgeon WA, Hand GA. Spiritual well-being, sleep disturbance, and mental and physical health status in HIV-infected individuals. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(2):125–39.

Phillips KD, Moneyham L, Murdaugh C, Boyd MR, Tavakoli A, Jackson K, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression as barriers to adherence. Clin Nurs Res. 2005;14(3):273–93.

Ramamoorthy V, Campa A, Rubens M, Martinez SS, Fleetwood C, Stewart T, et al. Caffeine and insomnia in people living with HIV from the Miami adult studies on HIV (MASH) cohort. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2017;28(6):897–906.

Reda AA. Reliability and validity of the Ethiopian version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in HIV infected patients. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16049.

Redman K. Sleep quality and immune changes in HIV positive people in the first six months of starting highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART); n.d.

Reid S, Dwyer J. Insomnia in HIV infection: a systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and management. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(2):260–9.

Rubinstein ML, Selwyn PA. High prevalence of insomnia in an outpatient population with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998a;19(3):260–5.

Rubinstein ML, Selwyn PA. High prevalence of insomnia in an outpatient population with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998b;19(3):260–5.

Saberi P, Neilands TB, Johnson MO. Quality of sleep: associations with antiretroviral nonadherence. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(9):517–24.

Santos IK, Azevedo KP, Melo FC, Lima KK, Pinto RS, Dantas PM, et al. Lifestyle and sleep patterns among people living with and without HIV/AIDS. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018;51(4):513–7.

Sharpley CF. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a step by step treatment manual, vol. 586. New York: The Guilford Press; 1985. p. A69–80. Behav Chang 1988;5(3):139–40.

Taibi DM. Sleep disturbances in persons living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(1):S72–85.

Taibi DM, Price C, Voss J. A pilot study of sleep quality and rest–activity patterns in persons living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(5):411–21.

Takeda A, Watanuki E, Koyama S. Effects of inhalation aromatherapy on symptoms of sleep disturbance in the elderly with dementia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:87–92.

Van Rie A, Sengupta S, Pungrassami P, Balthip Q, Choonuan S, Kasetjaroen Y, et al. Measuring stigma associated with tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in southern Thailand: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of two new scales. Tropical Med Int Health. 2008;13(1):21–30.

Voinescu BI, Szentagotai-Tatar A. Sleep hygiene awareness: its relation to sleep quality and diurnal preference. J Mol Psychiatry. 2015;3(1):1.

Webel AR, Higgins PA. The relationship between social roles and self-management behavior in women living with HIV/AIDS. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(1):e27–33.

Webel AR, Moore SM, Hanson JE, Patel SR, Schmotzer B, Salata RA. Improving sleep hygiene behavior in adults living with HIV/AIDS: a randomized control pilot study of the SystemCHANGETM–HIV intervention. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(2):85–91.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the University of Gondar and Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital for ethical approval. The authors would also like to thank staffs of Zewuditu Memorial Hospital for their unreserved support in all stages this research work.

Funding

There was no specific fund secured for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM and SS conceived the idea, write the proposal and participated in the data collection, analysis and manuscript writing. ZB took major roles in the data collection, soft ware analysis, manuscript writing and revision. All authors read the final version of the manuscript, and gave approval for this version of the manuscript to be considered for publication. All Authors also agreed to be equally accountable for all aspects of this research work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University of Gondar. Supportive letter was also obtained from Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital. Each participant was requested to provide written consent of their participation after delivering a brief explanation regarding the purpose and objectives of the study. Study participants were also informed that there will not be any harm imposed towards them due to their participation, and have full freedom to refuse or discontinue their participation at any time they want. For the purpose of confidentiality, participant’s name and phone numbers were not recorded at the time of data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mengistu, N., Belayneh, Z. & Shumye, S. Knowledge, practice and correlates of sleep hygiene among people living with HIV/AIDS attending anti-retroviral therapy at Zewditu Memorial Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Sleep Science Practice 4, 9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-020-00044-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-020-00044-0