Abstract

Over the last 10 years, interest in pediatric tuberculosis (TB) has increased dramatically, together with increased funding and research. We have a better understanding of the burden of childhood TB as well as a better idea of how to diagnose it. Our appreciation of pathophysiology is improved and with it investigators are beginning to consider pediatric TB as a heterogeneous entity, with different types and severity of disease being treated in different ways. There have been advances in how to treat both TB infection and TB disease caused by both drug-susceptible as well as drug-resistant organisms. Two completely novel drugs, bedaquiline and delamanid, have been developed, in addition to the use of older drugs that have been re-purposed. New regimens are being evaluated that have the potential to shorten treatment. Many of these drugs and regimens have first been investigated in adults with children an afterthought, but increasingly children are being considered at the outset and, in some instances studies are only conducted in children where pediatric-specific issues exist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

How do children get tuberculosis?

If a child is exposed to an individual, usually an adult, with infectious pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) disease they are at risk of inhaling aerosolised Mycobacterium tuberculosis and becoming infected. Whether they become infected or not following exposure will depend on the integrity of their mucosal defences, their innate immune system, the virulence of the mycobacterium and the infective dose. Once infection has occurred the adaptive immune system recognises the bacilli and may clear the organism, become overrun by it or reach an equilibrium in which the immune system fails to eradicate the mycobacteria but prevents them from proliferating. This final situation is termed TB infection. In the future, the bacilli may overcome the immune system and progress to TB disease [1–3].

Other than occasionally having brief, viral-like symptoms, children with TB infection usually have no clinical symptoms or signs, and radiology shows no evidence of TB disease. TB infection is detected through a positive tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). The risk of progressing from infection to disease is governed by a number of factors but age and immune status are central. From studies that examined the natural history of TB, conducted prior to the chemotherapy era, we know that infected infants have a 50% risk of progression to disease, with the risk decreasing with age through childhood but increasing again as children enter adolescence [4, 5]. HIV-positive adults not on antiretroviral therapy have a 7–10% risk of developing TB each year following TB infection; [6, 7] the risk is likely to be similar for children. Children with malnutrition or other forms of immune deficiency have also been shown to be more vulnerable [8]. If children are identified at the point that they have TB infection, the risk of progression to disease can be markedly reduced by giving preventive therapy.

Children with TB disease have a wide range of clinical presentations. The most common presentation in young children is intra- or extra-thoracic lymph node disease. However, young children (<3 years) are also more likely than older children or adults to develop the most severe forms of disseminated TB, such as TB meningitis or miliary TB. As children get older (starting from about 8 years of age) they are more likely to develop adult-type disease, including cavitary pathology. Due to this variety of clinical forms, investigators are increasingly exploring whether it is possible to divide children into those with severe disease and non-severe disease, using consistent definitions, with the possibility that those with non-severe pathology might be treated with fewer drugs and for shorter durations (Fig. 1) [9].

How many children in the world have TB?

This topic is covered in detail in the article by Jenkins in this series [10]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR)-TB is defined as disease caused by M. tuberculosis resistant to rifampicin and isoniazid, whereas extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-TB is defined as disease caused by MDR organisms with additional resistance to a fluoroquinolone and a second-line injectable medication. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 million children developed TB in 2014 [11]. Only 358, 521 children were diagnosed, treated and reported to the WHO that year, suggesting that about two thirds of the children that develop TB each year remain undiagnosed, untreated or were not reported. Investigators have estimated that about 30,000 children develop MDR-TB each year [10, 12, 13]. Given that only 1000 children have been described in the entire medical literature as having been treated for MDR-TB at any point [14], under-diagnosis and under-treatment is likely to be even worse for MDR-TB.

Diagnosing TB infection and TB disease

Both TB infection and TB disease can be challenging to diagnose with certainty in children [15]. The TST and IGRA are associated with impaired sensitivity and specificity in children; [16–19] children can therefore be assumed to have TB infection if they have been heavily exposed to an infectious case of TB. If they are at high risk of disease progression (< 5 years of age or HIV-infected) and they have been exposed to a case of drug-susceptible TB, then WHO recommends that they be given preventive treatment without the need for TST or IGRA testing [20]. In most contexts only a small proportion of the children (often fewer than 30%) that are treated for TB disease have a bacteriologically confirmed diagnosis [21]. Treated cases are therefore confirmed or presumed. For research purposes, investigators have tried to quantify the confidence that is given to the diagnosis of presumed TB and comprehensive definitions have been developed through consensus to describe confirmed, probable and possible TB for both drug-susceptible (DS) [22] and drug-resistant (DR) TB disease [23]. For children presumed to have DR-TB, multiple microbiological samples should be taken, ideally before treatment. Once samples are taken, however, the child should be treated with a regimen designed on the assumption that they have the same drug susceptibility test (DST) pattern as the identified source case [24, 25].

Treating drug-susceptible tuberculosis infection

What is the recommended treatment of drug-susceptible TB infection (LTBI) in children?

Isoniazid given for 6 or 9 months has been shown to be very effective in preventing the progression from TB infection to disease [26] and a number of studies demonstrate that 3 months of isoniazid and rifampicin is also an effective regimen [27]. Rifampicin alone is likely to be effective if given for 3 or 4 months [28]. However, providing daily therapy to a child who is clinically well can be challenging for many parents; adherence is frequently poor, particularly in high burden settings [29, 30].

Are there any alternatives?

In 2011, the results of a large trial were published which had evaluated once weekly rifapentine and high-dose isoniazid for 3 months (12 dosing episodes) against 9 months of daily isoniazid [31]. This demonstrated that the shorter, once-weekly regimen was as effective in preventing TB disease as a 9-month daily isoniazid regimen and was also associated with better adherence. Although the study did include children above the age of 2 years, the investigators did not feel that there were sufficient children in the trial to be confident of the adverse events profile in pediatric populations. To that end, the study continued to recruit children for a further 2 years until more than 1000 children had been enrolled [32]. This found the 3-month regimen to be associated with higher completion rates and limited toxicity. Detailed pharmacokinetic studies and extensive modelling provide good evidence for the best dosage to give children when using either whole tablets or crushed tablets [33]. This regimen should still be evaluated in the most vulnerable age group of less than 2 years.

Treating drug-susceptible tuberculosis disease

What is the recommended treatment of drug-susceptible TB disease in children?

The WHO recommends that children with pulmonary DS-TB are treated with 2 months of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide followed by 4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid. They advise that ethambutol should be added for the first 2 months in children with extensive disease or where rates of HIV infection and/or isoniazid resistance are high, irrespective of the child’s age [20]. This regimen is effective and is associated with few adverse events; [34] optic neuritis is an extremely rare adverse effect at the dosages advised [35]. Due to emerging pharmacokinetic evidence, the recommended dosages of these first-line anti-TB medications were revised in 2010 as children metabolise the drugs more rapidly than adults resulting in a lower serum concentration following the same mg/kg dosage [36]. It is only using the revised dosages that young children achieve the target serum concentrations that have been shown to be associated with efficacy in adult studies [37]. Following the 2010 revision of pediatric TB dosing recommendations, the ratio of individual medications included in the fixed dose combination (FDC) tablets similarly required updating. A new appropriately dosed, scored, dispersible and palatable pediatric FDC tablet was launched in December 2015; these tablets are expected to be available for use by the end of 2016 [38].

Is it possible to shorten TB treatment?

Six months is a long time to treat a child and a number of adult studies have recently been completed that aimed to shorten treatment to 4 months using alternative regimens. In the RIFAQUIN trial adults were randomised to one of three regimens: (i) the traditional 6-month WHO-recommended regimen; (ii) 2 months of daily ethambutol, moxifloxacin, rifampicin and pyrazinamide followed by 2 months of twice weekly moxifloxacin and rifapentine; and (iii) 2 months of daily ethambutol, moxifloxacin, rifampicin and pyrazinamide followed by 4 months of once weekly moxifloxacin and rifapentine [39]. Although the 4-month regimen was inferior to the standard course of treatment (more patients relapsed), the alternative 6-month regimen, in which patients only had to take treatment once a week in the continuation phase, was non-inferior. This raises the exciting prospect of once weekly treatment for children in the continuation phase of treatment. The OFLOTUB trial compared the standard 6-month regimen with a new experimental regimen in adults, in this case gatifloxacin, rifampicin and isoniazid for 4 months with additional pyrazinamide for the first 2 months [40]. As with the RIFAQUIN trial, the shortened regimen was found to be inferior with more unfavourable outcomes (death, treatment failure, recurrence) in the shorter treatment group. However, there was great variation by country and also by HIV status and body mass index (outcomes were similar between the two treatments for malnourished patients and those with HIV). This suggests that there may be a role for shortened treatment in some patient populations or it might work in certain health systems. The final adult study, the REMox trial, compared the WHO adult first-line regimen to two experimental arms: (i) 4 months of moxifloxacin, isoniazid and rifampicin with additional pyrazinamide for the first 2 months; and (ii) 4 months of moxifloxacin and rifampicin with ethambutol and pyrazinamide for the first 2 months. More rapid culture-conversion was seen in the moxifloxacin-containing arms but the shortened regimens were inferior to the WHO regimen [41].

A pediatric trial, SHINE, is due to soon start at a number of sites in Africa, and also in India, that will evaluate whether children with non-severe disease can be treated successfully with only 4 months of treatment [42]. If more effective contact tracing occurs following the diagnosis of TB in adults, it is expected that more children with TB will be detected at an earlier stage in their disease process. If these children can be safely treated with shorter treatment regimens, better adherence and cheaper treatments would be expected.

What is the best treatment for TB meningitis?

The WHO suggests that children with TB meningitis (TBM) should be treated for 2 months with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol followed by 10 months with isoniazid and rifampicin at the standard dosages [20]. There are concerns that this regimen may not be ideal. Isoniazid and pyrazinamide penetrate well into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), rifampicin penetrates moderately when there is meningeal inflammation and poorly after this has subsided, with ethambutol having almost no penetration [43–45]. Therefore, during the first 2 months of treatment two drugs are being given with good CSF penetration and for the subsequent 10 months effectively only one drug is being given. In areas of increased rates of isoniazid resistance, many children are left without any effective treatment after the first 2 months. Further, the dosages recommended for treatment do not fully consider the penetration into the CSF and it is expected that higher dosages are required to achieve adequate CSF concentrations. Outcomes for children with TBM are very poor [46]. One group in Cape Town, South Africa, have been treating TBM in children with a short, intensive regimen for a number of years [47–49]. This consists of high-dose isoniazid (15-20 mg/kg), rifampicin (20 mg/kg), pyrazinamide (40 mg/kg) and ethionamide (20 mg/kg) for 6 months. Outcomes are reasonable and the regimen is well tolerated. Although an exciting trial in adults with TBM in Indonesia showed that high dosages of rifampicin (given intravenously) combined with moxifloxacin improved outcome [50], a further study in Vietnam failed to demonstrate a protective effect of higher dose rifampicin and the addition of levofloxacin. A pediatric trial, TBM-KIDS, has started in Malawi and India and aims to evaluate the pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy of levofloxacin and high-dose rifampicin in TBM [51].

The role of immune modulators in pediatric TBM is still unclear. A number of trials have demonstrated that the use of steroids offers a modest benefit on death and severe disability [52]. However, this may be restricted to only those with certain host genotypes [53] and the dosage to give children remains unclear [54]. A trial of high-dose thalidomide as an immune modulator in TBM was stopped early due to worse outcomes in the intervention group [55]. However, thalidomide at a lower dose has since been used successfully in the treatment of optochiasmatic arachnoiditis and tuberculomas/pseudoabscesses in children [56, 57]. The effect of aspirin is unclear. In one pediatric trial aspirin demonstrated a benefit [58], whereas in another it did not [59].

Treating drug-resistant tuberculosis infection

How does drug-resistant TB develop?

Drug resistance can be acquired through sequential, selective pressure in the face of inadequate therapy. Here, spontaneously occurring mutants are favoured that provide resistance against individual drugs. This process usually takes place in the presence of a high bacillary load, where previously drug-susceptible organisms develop resistance within one human host. Alternatively, resistance can be transmitted where mycobacteria, already resistant, are transmitted to a new host. Additionally, a combination of the two can occur when one individual receives a mycobacterium already resistant to one or more medications and then in the face of inadequate treatment develops resistance to further antibiotics (resistance amplification). Children usually have transmitted resistance, as disease is normally paucibacillary, making acquired resistance less likely.

How should we investigate a child who has been exposed to a drug-resistant TB source case?

If a child has been exposed to an infectious source case with DR-TB they should be assessed for evidence of TB disease. This would include a comprehensive symptom screen, clinical examination and, where available, chest radiography. Any concerns that the child has TB disease should necessitate further investigation. If the child is symptom-free, growing well, with no concerning clinical signs, they should be evaluated for risk of infection. Where available, TST and/or IGRA could be employed to evaluate the risk of infection but if they are unavailable an assessment can be made on the basis of exposure.

How should we treat a healthy child who has been exposed to a drug-resistant TB source case?

Children exposed to either rifampicin mono-resistant TB or isoniazid mono-resistant TB can usually be given either isoniazid or rifampicin alone, respectively. The correct management of children exposed to MDR-TB is unclear [60], with a limited evidence base to support policy [61, 62]. Using isoniazid and/or rifampicin (the two drugs for which there is a strong evidence base for preventive therapy) is unlikely to be effective [63] as the organism is, by definition, resistant to these drugs. International guidelines are highly variable [64]. The British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence advises follow up with no medical treatment [65], as does the WHO [66]. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise giving two drugs to which the source case’s strain is susceptible [67]. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control suggest that either treatment or close follow up are legitimate options [68].

Only a few studies have assessed preventive therapy in MDR-TB child contacts. In Israel, 476 adult and child contacts of 78 pulmonary MDR-TB patients were evaluated. Twelve were given a tailored preventive therapy regimen, 71 were given isoniazid, six were given other treatments and 387 were not given any treatment. No contacts developed TB [69]. In Cape Town, from 1994 to 2000, 105 child contacts of 73 MDR-TB source cases were identified and followed up. Two (5%) of the 41 children who received tailored preventive therapy developed TB as opposed to 13 (20%) of the 64 children who were not given any [70]. In a retrospective study in Brazil, 218 contacts of 64 MDR-TB source cases were given isoniazid, while the remainder were observed without treatment. The rate of TB was similar in the group who were given isoniazid (1.2 per 1000-person-months of contact) compared to those who were not (1.7 per 1000-person-months of contact; p = 0.47). In two outbreaks in Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, five MDR-TB source cases were identified. Of 232 contacts identified, 119 were offered preventive therapy, of which 104 initiated a fluoroquinolone-based regimen. None of those who started preventive therapy developed TB disease, whereas three of the 15 who did not take treatment did [68, 71]. A prospective study from Cape Town recruited 186 children during 2010 and 2011 who had been exposed to adult source cases with MDR-TB. All were offered three-drug preventive therapy with ofloxacin, ethambutol and high dose isoniazid. Six children developed TB and one infant died. Factors associated with poor outcome were: age less than 12 months, HIV infection and poor adherence [72]. Although a clinical trial is urgently needed to assess how to best manage children exposed to MDR-TB, these studies together suggest that providing preventive therapy may be effective in stopping the transition from infection to disease. Three randomised trials are planned. VQUIN are recruiting adult contacts of MDR-TB in Vietnam and randomising them to either levofloxacin or placebo. TB-CHAMP will take place in four sites in South Africa and recruit children under 5 years of age following MDR-TB household exposure. This trial will also randomise contacts to levofloxacin or placebo. PHOENIx will take place at a number of sites globally and recruit adults and children with all patients randomised to either delamanid or isoniazid. Although the results of these trials are eagerly awaited, an expert group, convened in Dubai in 2015, concluded that there is currently enough observational evidence to treat high risk contacts with a fluoroquinolone-based regimen [73].

How should we follow up these children?

As 90% of children who develop TB disease do so within 12 months and as almost all do so within 2 years [74], follow up for at least 12 months is advisable whether preventive therapy is given or not. The WHO and several other guidelines recommend 2 years of follow up. Clinical follow-up is likely sufficient but where resources permit, chest radiology at 3–6-month intervals can detect early disease when symptoms may not be obvious.

Treating drug-resistant tuberculosis disease

How do you design a regimen for a child in order to treat for drug-resistant TB?

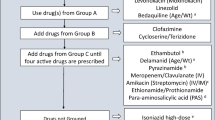

In 2016 the WHO updated its recommendations for the management of MDR-TB [75]. It also re-structured the groupings into which the different drugs were placed (Table 1). Drugs are added to the regimen in the following order (as long as the drug is likely to be effective): first a fluoroquinolone is added (WHO Group A), followed by a second-line injectable medication (Group B). Further drugs from Group C are added until four likely effective drugs are present. To strengthen the regimen or to provide additional drugs to make four effective drugs, agents from Group D can be added (Fig. 2).

Although for adults it is recommended that the intensive phase (including the injectable agent) should last 8 months and the full duration of therapy should be no less than 20 months, the 2016 WHO guidelines recognise the fact that many children with non-severe disease have been successfully treated with shorter regimens and many with no injectable in the regimen. Given the high rates of irreversible hearing loss, consideration should be given to either omitting the injectable agent or giving it for a shorter period of time (3–4 months) in children with non-severe disease. Total duration of therapy could also be shorter (12–15 months) than for adults.

How should children being treated for drug-resistant TB be followed up and monitored?

Children should be monitored for three reasons: to determine response to therapy; to identify adverse events early; and to promote adherence. A suggested monitoring schedule, which should be adapted to local conditions and resources, is demonstrated in Table 2.

Response to therapy includes clinical, microbiological and radiological monitoring. Children should be clinically assessed on a regular basis to identify symptoms or signs that might signal response: activity levels, respiratory function and neurological development. Height and weight should be measured monthly and, for children with pulmonary disease, respiratory samples for smear microscopy and culture (not genotypic evaluation during follow-up) should be collected where possible. Children with pulmonary disease should have a chest radiograph at 3 and 6 months and at any time if clinically indicated. It is also useful to have a chest radiograph at the end of therapy to provide a baseline for follow-up.

Children should be assessed clinically for adverse events on a regular basis. Prior to the start of treatment, children should have a baseline assessment of thyroid function, renal function and have audiological and vision examinations. Both ethionamide and para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) have been shown to cause hypothyroidism [76–81] and the thyroid function should be checked every 2 months. The injectable drugs can cause renal impairment and hearing loss [82–85]. Renal function should be determined every 2 months; hearing evaluation should be done at least every month while on an injectable drug and 6 months after stopping the agent, as hearing loss can continue after discontinuing the drug. The testing of hearing is age-dependent and for those older than five with normal neuro-development, pure tone audiometry (PTA) is the best assessment. Otoacoustic emissions can be used to test the hearing in younger children but visual testing is challenging for this age group. Children being given ethambutol who are able to co-operate with colour vision testing, should be assessed monthly, using an appropriate Ishihara chart. This is usually possible from the age of five. Clinicians should, however, be reassured that the incidence of ocular toxicity is very rare when ethambutol is given at the recommended dosage [86].

What are the common adverse effects associated with treating children for drug-resistant TB?

Most anti-TB drugs can cause gastrointestinal upset and rash but in most instances, these resolve without treatment and without compromising therapy. Severe cutaneous drug reactions, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, necessitate immediate cessation of all drugs until the symptoms have resolved. Gastrointestinal upset is most pronounced with ethionamide and PAS and frequently this can be managed without stopping the drug by dose escalation, by dividing the dose or by anti-emetics in older children/adolescents. If either colour vision or hearing are found to be deteriorating, consideration should be given to stopping the ethambutol (vision) or injectable medication (hearing); if not a failing regimen, substitution with another drug could be considered. If the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated and the free T4 is low then consideration should be given to starting thyroxine substitution. Peripheral neuropathy can be treated by either increasing the dose of pyridoxine or reducing the dose of isoniazid or linezolid. If it persists, the causative drug should be stopped. Determining the cause of neuropsychiatric adverse events can be complicated as many drugs can cause dysfunction. Dose reduction may help, but if symptoms persist the likely drug should be stopped. Joint problems can be caused by pyrazinamide and the fluoroquinolones and management options include reducing or stopping one/both of these drugs. Hepatotoxicity usually starts with new-onset vomiting. Clinical hepatitis (tender liver, visible jaundice) necessitates immediate cessation of all hepatotoxic drugs. These include rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethionamide, PAS, beta-lactams and macrolides. Treatment should continue with the remaining drugs and consideration given to starting any other available medications that are not hepatotoxic. The hepatotoxic drugs can be re-introduced if felt to be necessary, one-by-one every 2 days, while checking the liver enzymes to identify the possible causative drug(s).

How successful is treatment for drug-resistant TB in children?

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2012, identified only eight studies reporting the treatment of MDR-TB in children; 315 children were included in the meta-analysis [87]. Successful outcomes were seen in 82% of children, as compared to 62% in adults [88, 89]. It is difficult to draw too many firm conclusions from such small numbers but it does appear that if children are identified, diagnosed and treated with appropriate therapy, outcomes are very good. However, these individualised approaches require high levels of expertise from the clinicians who manage these children, the treatment is long (up to 18 months and longer) and is associated with significant adverse events.

Since this systematic review there have been a large number of publications that have described the treatment of MDR-TB in children [90–108]. In one study from Cape Town, Western Cape children were classified as having had severe or non-severe disease [108]. The children with non-severe disease were younger, better nourished, less likely to have HIV infection, were less likely to have confirmed disease and less likely to have sputum smear-positive TB. They were more commonly treated as outpatients, less likely to receive an injectable medication and were given shorter total durations of medication (median 12 months vs. 18 months in the severe cases). A study from four provinces in South Africa (outside the Western Cape) collected routine data on the treatment of more than 600 children with MDR-TB. Although mortality was slightly higher than in other studies at 20%, these children were often treated outside of specialist centres. In preparation for the revision to the WHO DR-TB guidelines an individual patient systematic review and meta-analysis was commissioned to evaluate the treatment of children with MDR-TB. More than a thousand children were included and treatment outcomes were successful in 77% of cases [14].

In addition to these studies, there have been a number of pharmacokinetic investigations of second-line anti-TB drugs in children [109–111] and novel delivery systems have been designed [112]. A consensus statement has been developed suggesting definitions that could be used in pediatric MDR-TB research [23] and a number of guidelines have been published [113–116], as well as a practical field guide [117].

Are there any new drugs to treat children for drug-resistant TB?

A couple of antibiotics traditionally used for the treatment of other infections are now more commonly used [118–122] and have been promoted in the WHO drug grouping. Linezolid was shown to be highly effective in adult patients with XDR-TB who were failing therapy [123]. Almost all the adults developed adverse effects, some severe, necessitating cessation of therapy. A systematic review demonstrated that linezolid could be an effective component of DR-TB treatment regimens but is associated with significant adverse events [124]. Linezolid in children seems as effective as in adults, but with fewer adverse events [95, 125–127]. Clofazimine, traditionally an anti-leprosy drug, has also gained a great deal of interest recently mainly due to its central role in the Bangladesh regimen (discussed later) [128]. A systematic review of clofazimine use in DR-TB suggested that it should be considered as an additional drug in DR-TB treatment [129]. Although few children have been described as treated for TB using clofazimine, there is good experience of using the drug in children with leprosy. Apart from reversible skin discoloration and gastrointestinal disturbance, it appears to be well-tolerated [130].

Two new drugs have been licenced and given conditional approval by WHO: bedaquiline and delamanid. Bedaquiline is a diarylquinoline that acts by inhibiting intracellular ATP synthase. It has a very long half-life and is effective against actively replicating as well as dormant bacilli. In clinical trials it has been shown to reduce the time to culture conversion in adults with pulmonary TB, as well as increasing the proportion that do culture-convert. [131] Although it has not been licenced for use in children, bioequivalence studies of two pediatric formulations (granules and water-dispersible tablets) have been conducted [132] and pharmacokinetic and safety studies are planned. The CDC advises that on a case-by-case basis bedaquiline might be considered in children when ‘an effective treatment regimen cannot otherwise be provided’ [133]. Delamanid is a nitroimidazole (like metronidazole) and acts predominantly on mycolic acid synthesis to stop cell wall production. It has been shown to increase culture conversion and also improve outcome in adult studies [134, 135]. Pediatric formulations have been developed and pharmacokinetic and safety studies are underway in children [136]. A single case report describes the use of delamanid in a 12-year-old boy who was failing treatment and was infected with a highly resistant organism [137]. The Sentinel Project of Pediatric Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis has produced clinical guidance to assist in the use of these new agents [138]. They suggest that both drugs could be considered in children older than 12 years and, in certain circumstances, in children younger than this. It is also suggested that consideration be given to using delamanid in place of the injectable drug in pediatric regimens; this would need careful follow-up and documentation of efficacy and safety.

Are there any new regimens to treat children for drug-resistant TB?

In 2010, a seminal article was published describing an observational study conducted in Bangladesh [128]. Sequential cohorts of patients (mainly but not all adults) with MDR-TB were given different treatment regimens, each differing from the previous by the substitution or addition of one drug. The final cohort were given a 9-month regimen, consisting of kanamycin, clofazimine, gatifloxacin, ethambutol, high-dose isoniazid, pyrazinamide and prothionamide for 4 months, followed by gatifloxacin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and clofazimine for 5 months. Of these patients, 88% had a favourable outcome (cured or treatment completed), compared to poorer outcomes for the five previous cohorts who had been given longer regimens (typically 15 months) with drugs including an earlier generation fluoroquinolone (ofloxacin) and without clofazimine. This study has generated much interest and has led to a number of trials and observational cohorts which seek to further evaluate this 9–12 month regimen [139, 140]. The STREAM trial is a randomised, non-inferiority trial that compares a similar 9-month regimen to the standard WHO-recommended regimen. It should complete by the end of 2016 [141]. Although all of the individual drugs with the ‘Bangladesh regimen’ are available for children in some form and are used either to treat TB already or are used for other indications, children have not been included in STREAM. The 2016 WHO guidance has suggested that children could be considered for treatment with the 9–12 month regimen under the same conditions as adults, namely when confirmed or suspected of having MDR-TB and where resistance to the fluoroquinolones is not suspected. A single case report describes the treatment of an adolescent treated with this regimen [142].

Conclusions

There is currently unprecedented interest in pediatric TB with new drugs, new regimens and new approaches to the treatment of infection and disease for both DR- and DS-TB. We have a better understanding of the burden of childhood TB and better diagnostic tests. However, only a third of the children that develop TB are diagnosed, treated and notified. Children are still dying of this disease and TBM results in significant mortality and morbidity even if treated. Treatments for both TB infection and disease are long and the evidence base for the treatment of DR-TB is poor. We still have a long way to go and pediatric TB research still lags a long way behind research into adult TB.

New, shorter regimens are still required for the treatment of both infection and disease and for both DS- and DR-TB. Less toxic regimens are needed for the treatment of DR-TB disease and a better evidence base is needed for the treatment of DR-TB infection. Child-friendly formulations for all TB drugs are needed and our understanding of the pharmacokinetics of the second-line drugs needs further work. Although we have come a long way, there is still a long way to go.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DR:

-

Drug-resistant

- DS:

-

Drug-susceptible

- DST:

-

Drug susceptibility test

- FDC:

-

Fixed dose combination

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IGRA:

-

Interferon-gamma release assay

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis infection

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- PAS:

-

Para-aminosalicylic acid

- PTA:

-

Pure tone audiometry

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- TBM:

-

Tuberculous meningitis

- TSH:

-

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- TST:

-

Tuberculin skin test

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- XDR:

-

Extensively drug-resistant

References

Maartens G, Wilkinson RJ. Tuberculosis. Lancet. 2007;370(9604):2030–43.

Andersen P, Doherty TM, Pai M, Weldingh K. The prognosis of latent tuberculosis: can disease be predicted? Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(5):175–82.

Barry 3rd CE, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(12):845–55.

Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, et al. The clinical epidemiology of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(3):278–85.

Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, et al. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(4):392–402.

Guelar A, Gatell JM, Verdejo J, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1993;7(10):1345–9.

Selwyn PA, Hartel D, Lewis VA, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(9):545–50.

Singh M, Mynak ML, Kumar L, Mathew JL, Jindal SK. Prevalence and risk factors for transmission of infection among children in household contact with adults having pulmonary tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(6):624–8.

Wiseman CA, Gie RP, Starke JR, et al. A proposed comprehensive classification of tuberculosis disease severity in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(4):347–52.

Jenkins HE. The global burden of childhood tuberculosis. Pneumonia. 2016. doi 10.1186/s41479-016-0018-6.

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Dodd PJ, Sismanidis C, Seddon JA. The global burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis in children: a mathematical model. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(10):1193–201.

Jenkins HE, Tolman AW, Yuen CM, et al. Incidence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis disease in children: systematic review and global estimates. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1572–9.

Harausz E, Garcia-Prats AJ, Schaaf HS, et al. Global treatment outcomes in children with paediatric MDR-TB: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19 Suppl 2:S29.

Connell TG, Zar HJ, Nicol MP. Advances in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204 Suppl 4:S1151–8.

Mandalakas AM, Kirchner HL, Walzl G, et al. Optimizing the detection of recent tuberculosis infection in children in a high tuberculosis-HIV burden setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):820–30.

Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS, Gonzalez-Angulo Y, et al. The utility of an interferon gamma release assay for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection and disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(8):694–700.

Chiappini E, Accetta G, Bonsignori F, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25(3):557–64.

Laurenti P, Raponi M, de Waure C, Marino M, Ricciardi W, Damiani G. Performance of interferon-gamma release assays in the diagnosis of confirmed active tuberculosis in immunocompetent children: a new systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):131.

World Health Organization. Guidance for national tuberculosis programme on the management of tuberculosis in children. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21535en/s21535en.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

Zar HJ, Hanslo D, Apolles P, Swingler G, Hussey G. Induced sputum versus gastric lavage for microbiological confirmation of pulmonary tuberculosis in infants and young children: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;365(9454):130–4.

Graham SM, Ahmed T, Amanullah F, et al. Evaluation of tuberculosis diagnostics in children: 1. Proposed clinical case definitions for classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis disease. Consensus from an expert panel. J Infect Dis. 2012;205 Suppl 2:S199–208.

Seddon JA, Perez-Velez CM, Schaaf HS, et al. Consensus statement on research definitions for drug-resistant tuberculosis in children. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2013;2(2):100–9.

Shah NS, Yuen CM, Heo M, Tolman AW, Becerra MC. Yield of contact investigations in households of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):381–91.

Grandjean L, Gilman RH, Martin L, et al. Transmission of Multidrug-Resistant and Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis within Households: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001843.

Smieja MJ, Marchetti CA, Cook DJ, Smaill FM. Isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in non-HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD001363.

Bright-Thomas R, Nandwani S, Smith J, Morris JA, Ormerod LP. Effectiveness of 3 months of rifampicin and isoniazid chemoprophylaxis for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(8):600–2.

Sharma SK, Sharma A, Kadhiravan T, Tharyan P. Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD007545.

Garie KT, Yassin MA, Cuevas LE. Lack of adherence to isoniazid chemoprophylaxis in children in contact with adults with tuberculosis in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26452.

Marais BJ, van Zyl S, Schaaf HS, van Aardt M, Gie RP, Beyers N. Adherence to isoniazid preventive chemotherapy: a prospective community based study. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(9):762–5.

Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, et al. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2155–66.

Villarino ME, Scott NA, Weis SE, et al. Treatment for preventing tuberculosis in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial of a 3-month, 12-dose regimen of a combination of rifapentine and isoniazid. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):247–55.

Weiner M, Savic RM, Mac Kenzie WR, et al. Rifapentine pharmacokinetics and tolerability in children and adults treated once weekly with rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3:132–45.

Frydenberg AR, Graham SM. Toxicity of first-line drugs for treatment of tuberculosis in children: review. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(11):1329–37.

World Health Organization. Ethambutol efficacy and toxicity: literature review and recommendations for daily and intermittent dosage in children. (Who/Htm/Tb/2006.365; Who/Fch/Cah/2006.3). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

World Health Organization. Rapid Advice. Treatment of tuberculosis in children. WHO/HTM/TB/2010.13. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Thee S, Seddon JA, Donald PR, et al. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide in children younger than two years of age with tuberculosis: evidence for implementation of revised World Health Organization recommendations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(12):5560–7.

TB Alliance. TB Alliance Receives Grant from UNITAID to Develop Pediatric TB Drugs. 2012. Available at: http://www.tballiance.org/newscenter/view-brief.php?id=1058#sthash.xLlC3Bn0.dpufhttp://www.tballiance.org/newscenter/view-brief.php?id=1058. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

Jindani A, Harrison TS, Nunn AJ, et al. High-dose rifapentine with moxifloxacin for pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1599–608.

Merle CS, Fielding K, Sow OB, et al. A four-month gatifloxacin-containing regimen for treating tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1588–98.

Gillespie SH, Crook AM, McHugh TD, et al. Four-month moxifloxacin-based regimens for drug-sensitive tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1577–87.

SHINE study: Shorter treatment for minimal TB in children. Available at: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN63579542 Accessed 2 Feb 2015.

Donald PR. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of antituberculosis agents in adults and children. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2010;90(5):279–92.

Marx GE, Chan ED. Tuberculous meningitis: diagnosis and treatment overview. Tuberc Res Treat. 2011;2011:798764.

Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):999–1010.

Chiang SS, Khan FA, Milstein MB, et al. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(10):947–57.

van Well GT, Paes BF, Terwee CB, et al. Twenty years of pediatric tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort study in the western cape of South Africa. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e1–8.

Donald PR, Schoeman JF, Van Zyl LE, De Villiers JN, Pretorius M, Springer P. Intensive short course chemotherapy in the management of tuberculous meningitis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2(9):704–11.

van Toorn R, Schaaf HS, Laubscher JA, van Elsland SL, Donald PR, Schoeman JF. Short Intensified Treatment in Children with Drug-susceptible Tuberculous Meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(3):248–52.

Ruslami R, Ganiem AR, Dian S, et al. Intensified regimen containing rifampicin and moxifloxacin for tuberculous meningitis: an open-label, randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):27–35.

Innovative PK/PD approaches to optimize TBM Treatment in Children (PATCH Study). Available at: https://www.collectiveip.com/grants/NIH:8697534. Accessed 2 Feb 2015.

Prasad K, Singh MB. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD002244.

Tobin DM, Roca FJ, Oh SF, et al. Host genotype-specific therapies can optimize the inflammatory response to mycobacterial infections. Cell. 2012;148(3):434–46.

Shah I, Meshram L. High dose versus low dose steroids in children with tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21(5):761–4.

Schoeman JF, Springer P, van Rensburg AJ, et al. Adjunctive thalidomide therapy for childhood tuberculous meningitis: results of a randomized study. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(4):250–7.

Schoeman JF, Andronikou S, Stefan DC, Freeman N, van Toorn R. Tuberculous meningitis-related optic neuritis: recovery of vision with thalidomide in 4 consecutive cases. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(7):822–8.

Schoeman JF, Fieggen G, Seller N, Mendelson M, Hartzenberg B. Intractable intracranial tuberculous infection responsive to thalidomide: report of four cases. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(4):301–8.

Misra UK, Kalita J, Nair PP. Role of aspirin in tuberculous meningitis: a randomized open label placebo controlled trial. J Neurol Sci. 2010;293(1-2):12–7.

Schoeman JF, Janse van Rensburg A, Laubscher JA, Springer P. The role of aspirin in childhood tuberculous meningitis. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(8):956–62.

Seddon JA, Godfrey-Faussett P, Hesseling AC, Gie RP, Beyers N, Schaaf HS. Management of children exposed to multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(6):469–79.

van der Werf MJ, Langendam MW, Sandgren A, Manissero D. Lack of evidence to support policy development for management of contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients: two systematic reviews. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(3):288–96.

Fraser A, Paul M, Attamna A, Leibovici L. Drugs for preventing tuberculosis in people at risk of multiple-drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD005435.

Sneag DB, Schaaf HS, Cotton MF, Zar HJ. Failure of chemoprophylaxis with standard antituberculosis agents in child contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(12):1142–6.

van der Werf MJ, Sandgren A, Manissero D. Management of contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in the European Union and European Economic Area. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(3):426.

National Institute for Health And Care Excellence. Tuberculosis. NG33. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng33. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

World Health Organization. Guidance for National Tuberculosis Programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.371, WHO/FCH/CAH/2006.7. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_HTM_TB_2006.371_eng.pdf. Accessed July 2013.

Centres for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Management of persons exposed to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(RR-11):61-71.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Management of contacts of MDR TB and XDR TB patients. 2012. Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/201203-Guidance-MDR-TB-contacts.pdf. Accessed July 2013.

Attamna A, Chemtob D, Attamna S, et al. Risk of tuberculosis in close contacts of patients with multidrug resistant tuberculosis: A nationwide cohort. Thorax. 2009;64(3):271.

Schaaf HS, Gie RP, Kennedy M, Beyers N, Hesseling PB, Donald PR. Evaluation of young children in contact with adult multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis: a 30-month follow-up. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):765–71.

Bamrah S, Brostrom R, Setik L, Fred D, Kawamura M, Mase S. An ounce of prevention: treating MDR-TB contacts in a resource-limited setting. In: Abstract. International Union of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Conference, Berlin, Germany 11-15 November, vol. FA-1--656-14. 2010. p. S180.

Seddon JA, Hesseling AC, Finlayson H, et al. Preventive therapy for child contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(12):1676–84.

Seddon JA, Fred D, Amanullah F, et al. Post-exposure managment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis contacts: evidence-based recommendations, Policy Brief No. 1. Dubai: Harvard Medical School Centre for Global Health Delivery - Dubai; 2015. Available at: http://sentinel-project.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Harvard-Policy-Brief_revised-10Nov2015.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2016.

Ferebee SH. Controlled chemoprophylaxis trials in tuberculosis. A general review. Bibl Tuberc. 1970;26:28–106.

World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis. 2016 update. WHO/HTM/TB/2016.04. 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/MDRTBguidelines2016.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2016.

McDonnell ME, Braverman LE, Bernardo J. Hypothyroidism due to ethionamide. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(26):2757–9.

Thee S, Zollner EW, Willemse M, Hesseling AC, Magdorf K, Schaaf HS. Abnormal thyroid function tests in children on ethionamide treatement (short communication). Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(9):1191–3.

Hallbauer UM, Schaaf HS. Ethionamide-induced hypothyroidism in children. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2011;26(3):161–3.

Soumakis SA, Berg D, Harris HW. Hypothyroidism in a patient receiving treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(4):910–1.

Moulding T, Fraser R. Hypothyroidism related to ethionamide. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1970;101(1):90–4.

Davies HT, Galbraith HJ. Goitre and hypothyroidism developing during treatment with P.A.S. Br Med J. 1953;1(4822):1261.

Selimoglu E. Aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(1):119–26.

Duggal P, Sarkar M. Audiologic monitoring of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis patients on aminoglycoside treatment with long term follow-up. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2007;7:5.

Peloquin CA, Berning SE, Nitta AT, et al. Aminoglycoside toxicity: daily versus thrice-weekly dosing for treatment of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(11):1538–44.

de Jager P, van Altena R. Hearing loss and nephrotoxicity in long-term aminoglycoside treatment in patients with tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(7):622–7.

Donald PR, Maher D, Maritz JS, Qazi S. Ethambutol dosage for the treatment of children: literature review and recommendations. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(12):1318–30.

Ettehad D, Schaaf HS, Seddon JA, Cooke GS, Ford N. Treatment outcomes for children with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(6):449–56.

Orenstein EW, Basu S, Shah NS, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(3):153–61.

Johnston JC, Shahidi NC, Sadatsafavi M, Fitzgerald JM. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e6914.

Esposito S, Bosis S, Canazza L, Tenconi R, Torricelli M, Principi N. Peritoneal tuberculosis due to multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pediatr Int. 2013;55(2):e20–2.

Katragkou A, Antachopoulos C, Hatziagorou E, Sdougka M, Roilides E, Tsanakas J. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in two children in Greece: report of the first extensively drug-resistant case. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(4):563–7.

Gegia M, Jenkins HE, Kalandadze I, Furin J. Outcomes of children treated for tuberculosis with second-line medications in Georgia, 2009-2011. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(5):624–9.

Williams B, Ramroop S, Shah P, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in UK children: presentation, management and outcome. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(6):1456–8.

Lapphra K, Sutthipong C, Foongladda S, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in children in Thailand. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(10):1279–84.

Rose PC, Hallbauer UM, Seddon JA, Hesseling AC, Schaaf HS. Linezolid-containing regimens for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis in South African children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(12):1588–93.

Satti H, McLaughlin MM, Omotayo DB, et al. Outcomes of comprehensive care for children empirically treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a setting of high HIV prevalence. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37114.

Shah I, Rahangdale A. Partial extensively drug resistance (XDR) tuberculosis in children. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48(12):977–9.

Shah I. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children from 2003 to 2005: a brief report. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2012;30(2):208–11.

Shah I, Chilkar S. Clinical profile of drug resistant tuberculosis in children. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49(9):741–4.

Shah I, Mohanty S. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in an HIV-infected girl. Natl Med J India. 2012;25(4):210–1.

Garazzino S, Scolfaro C, Raffaldi I, Barbui AM, Luccoli L, Tovo PA. Moxifloxacin for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a single center experience. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(4):372–6.

Chauny JV, Lorrot M, Prot-Labarthe S, et al. Treatment of tuberculosis with levofloxacin or moxifloxacin: report of 6 pediatric cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(12):1309–11.

Isaakidis P, Paryani R, Khan S, et al. Poor outcomes in a cohort of HIV-infected adolescents undergoing treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Mumbai, India. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68869.

Uppuluri R, Shah I. Partial extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in an HIV-infected child: a case report and review of literature. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(2):117–9.

Mignone F, Codecasa LR, Scolfaro C, et al. The spread of drug-resistant tuberculosis in children: an Italian case series. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(10):2049–56.

Santiago B, Baquero-Artigao F, Mejias A, Blazquez D, Jimenez MS, Mellado-Pena MJ. Pediatric drug-resistant tuberculosis in Madrid: family matters. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(4):345–50.

Rodrigues M, Brito M, Villar M, Correia P. Treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in adolescent patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):657–9.

Seddon JA, Hesseling AC, Godfrey-Faussett P, Schaaf HS. High treatment success in children treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: an observational cohort study. Thorax. 2014;69(5):458–64.

Thee S, Garcia-Prats AJ, McIlleron HM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of ofloxacin and levofloxacin for prevention and treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(5):2948–51.

Thee S, Seifart HI, Rosenkranz B, et al. Pharmacokinetics of ethionamide in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(10):4594–600.

Liwa AC, Schaaf HS, Rosenkranz B, Seifart HI, Diacon AH, Donald PR. Para-aminosalicylic acid plasma concentrations in children in comparison with adults after receiving a granular slow-release preparation. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59(2):90–4.

Furin J, Brigden G, Lessem E, Becerra MC. Novel pediatric delivery systems for second-line anti-tuberculosis medications: a case study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(9):1239–41.

Seddon JA, Furin JJ, Gale M, et al. Caring for children with drug-resistant tuberculosis: practice-based recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(10):953–64.

Al-Dabbagh M, Lapphra K, McGloin R, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: pediatric guidelines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(6):501–5.

Schaaf HS, Marais BJ. Management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: a survival guide for paediatricians. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2011;12(1):31–8.

Schaaf HS, Garcia-Prats AJ, Hesseling AC, Seddon JA. Managing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: review of recent developments. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27(3):211–9.

The Sentinel Project for Pediatric Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: a field guide. 2nd Ed. 2015. Available at: http://sentinel-project.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Field_Handbook_2nd_Ed_revised-no-logos_07Jul15.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

Alsaad N, Wilffert B, van Altena R, et al. Potential antimicrobial agents for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(3):884–97.

Zumla AI, Gillespie SH, Hoelscher M, et al. New antituberculosis drugs, regimens, and adjunct therapies: needs, advances, and future prospects. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):327–40.

Kaufmann SH, Lange C, Rao M, et al. Progress in tuberculosis vaccine development and host-directed therapies-a state of the art review. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(4):301–20.

Dooley KE, Obuku EA, Durakovic N, et al. World Health Organization group 5 drugs for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: unclear efficacy or untapped potential? J Infect Dis. 2013;207(9):1352–8.

Dooley KE, Mitnick C, Degroote MA, et al. Old drugs, new purpose: Retooling existing drugs for optimized treatment of resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(4):572–81.

Lee M, Lee J, Carroll MW, et al. Linezolid for treatment of chronic extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1508–18.

Zhang X, Falagas ME, Vardakas KZ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of therapy with linezolid containing regimens in the treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(4):603–15.

Garcia-Prats AJ, Rose PC, Hesseling AC, Schaaf HS. Linezolid for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis in children: a review and recommendations. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2014;94(2):93–104.

Kjollerstrom P, Brito MJ, Gouveia C, Ferreira G, Varandas L. Linezolid in the treatment of multidrug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in paediatric patients: Experience of a paediatric infectious diseases unit. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(6-7):556–9.

Pinon M, Scolfaro C, Bignamini E, et al. Two pediatric cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treated with linezolid and moxifloxacin. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):e1253–6.

Van Deun A, Maug AK, Salim MA, et al. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):684–92.

Dey T, Brigden G, Cox H, Shubber Z, Cooke G, Ford N. Outcomes of clofazimine for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(2):284–93.

Kroger A, Pannikar V, Htoon MT, et al. International open trial of uniform multi-drug therapy regimen for 6 months for all types of leprosy patients: rationale, design and preliminary results. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(5):594–602.

Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M, et al. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(23):2397–405.

Clinicaltrials.gov. A study to assess the relative bioavailability of TMC207 following single-dose administrations of two pediatric formulations in healthy adult participants. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01803373?term=bedaquiline&rank=6. Accessed 6 June 2014.

Provisional CDC guidelines for the use and safety monitoring of bedaquiline fumarate (Sirturo) for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-09):1-12.

Skripconoka V, Danilovits M, Pehme L, et al. Delamanid improves outcomes and reduces mortality in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(6):1393–400.

Gler MT, Skripconoka V, Sanchez-Garavito E, et al. Delamanid for multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2151–60.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Pharmacokinetic and safety trial to determine the appropriate dose for pediatric patients with multidrug resistant tuberculosis. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01856634. Accessed 6 June 2014.

Esposito S, D'Ambrosio L, Tadolini M, et al. ERS/WHO Tuberculosis Consilium assistance with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis management in a child: case study of compassionate delamanid use. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(3):811–5.

Sentinel Project on Pediatric Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Rapid clinical advice. The use of Delamanid and Bedaquiline for children with drug-resistant tuberculosis. 2016. Available at: http://sentinel-project.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Rapid-Clinical-Advice_May-16-2016.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2016.

Kuaban C, Kashongwe Z, Bakayoko A, et al. First results with a 9-month regimen for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in francophone Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19 Suppl 2:S46.

Kuaban C, Noeske J, Rieder HL, Ait-Khaled N, Abena Foe JL, Trebucq A. High effectiveness of a 12-month regimen for MDR-TB patients in Cameroon. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(5):517–24.

ISRCTN registry. The evaluation of a standardised treatment regimen of anti-tuberculosis drugs for patients with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Available at: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN78372190. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

Jay A, Catherine B, Krzysztof H, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in child successfully treated with 9-month drug regimen. Emerg Infect Dis J. 2015;21(11):2105.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ben Marais for his input into this article.

Funding

None declared.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Authors’ contributions

JAS wrote the first draft of the manuscript with critical input from HSS. Both authors revised and edited the manuscript and both approved the final version.

Competing interests

Both authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Seddon, J.A., Schaaf, H.S. Drug-resistant tuberculosis and advances in the treatment of childhood tuberculosis. Pneumonia 8, 20 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-016-0019-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-016-0019-5