Abstract

Background

Pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA), a conserved virulence factor essential for Streptococcus pneumoniae attachment to upper respiratory tract (URT) epithelia, is a potential vaccine candidate for preventing colonisation.

Methods

This cohort study was conducted in the Asaro Valley in the Eastern Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea, of which Goroka town is the provincial capital. The children included in the analysis were participants in a neonatal pneumococcal conjugate vaccine trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00219401) that was conducted between 2005 and 2009. We investigated the development of anti-PspA antibodies in the first 18 months of life relative to URT pneumococcal carriage in Papua New Guinean infants who experience one of the earliest and highest colonisation rates in the world. Blood samples and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from a cohort of 88 children at ages 3, 9, and 18 months to quantify immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels to PspA families 1 and 2 using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and to determine URT carriage.

Results

Seventy-three per cent (64/88) of infants carried S. pneumoniae at age 3 months; 85 % (75/88) at 9 months, and 83 % (73/88) at 18 months. PspA-IgG levels declined between ages 3 and 9 months (p < 0.001), then increased between 9 and 18 months (p < 0.001). At age 3 months, pneumococcal carriers showed lower PspA1-IgG levels (geometric mean concentration [GMC] 602 arbitrary units [AU]/ml, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 497–728) than non-carriers (GMC 1058 AU/ml [95 % CI 732–1530]; p = 0.008), while at 9 months, PspA1- and PspA2-IgG levels were significantly higher in carriers (PspA1: 186 AU/ml, 95 % CI 136–256; PspA2: 284 AU/ml, 95 % CI 192–421) than in non-carriers (PspA1 87 AU/ml, 95 % CI 45–169; PspA2 74 AU/ml, 95 % CI 34–159) (PspA1: p = 0.037, PspA2: p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Our findings confirm that PspA is immunogenic and indicate that natural anti-PspA immune responses are acquired through exposure and develop with age. PspA may be a useful candidate in an infant pneumococcal vaccine to prevent early URT colonisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pneumonia is responsible for more than a million deaths in young children every year and most of these deaths occur in the developing world [1, 2]. In Papua New Guinea (PNG), pneumonia is the most common cause of death in children less than 5 years of age [3] and Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of severe pneumonia. Dense upper respiratory tract (URT) pneumococcal carriage in PNG begins within weeks of birth (median age of acquisition of 19 days [4]), is persistent throughout childhood and is associated with increased risk of acquiring pneumococcal diseases [5].

The currently available 10-valent (Synflorix™; GSK Biologicals, Belgium) and 13-valent (Prevenar 13®; Pfizer, USA) pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) are effective in reducing URT carriage and preventing invasive disease caused by vaccine serotypes, but result to some extent in replacement carriage with non-vaccine serotypes, which in turn may lead to replacement disease, as was seen with the earlier marketed 7-valent PCV (Prevenar®; Pfizer, USA) [6–10]. In particular, in high-risk areas like PNG where the range of serotypes causing pneumococcal disease has always been broader than in areas of low endemicity, replacement by non-vaccine virulent serotypes is more likely to occur. New generation pneumococcal vaccines offering protection against all invasive pneumococcal serotypes, which could complement PCVs, would therefore be highly advantageous. Several pneumococcal surface proteins with vaccine potential have been identified and are currently the subject of research, including the pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA). PspA is a surface protein that hinders the activation and deposition processes of the host complement system, particularly complement component C3 [11, 12], hence protecting the bacteria from undergoing phagocytosis and clearance [13].

Animal models of carriage and infections have shown that PspA is highly immunogenic and capable of generating protective antibodies against pneumococcal URT carriage and infection [14–17]. The natural development of immunity to PspA in humans has not been extensively studied. Studies in children have been conducted in countries with moderate and low endemicity, including the Philippines, Australia, and Finland: these studies indicated that there is development of serum PspA family-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in association with S. pneumoniae exposure through carriage or infection [18–21]. A study by Laine et al. [22] in Kenya, a high-endemicity setting, demonstrated the development of naturally acquired antibodies to PspA in relation to age; however, this study did not look at pneumococcal carriage. In a comprehensive study conducted in mother–children pairs of refugees living on the Thailand–Myanmar border, Turner and colleagues [23] analysed antibody responses to 27 pneumococcal protein antigens, including PspA family 1 and PspA family 2: no associations between pneumococcal carriage and PspA-specific antibodies were found. Compared to the Thailand–Myanmar refugees’ study [23] where the median age of acquiring pneumococcal carriage was 45.5 days, young children in the highlands of PNG are colonised at a median age of 19 days, and all are colonised at least once by the age of 1 month [4]. Age at acquisition may be an important factor determining immune outcomes, considering that in the first few months of life the immune system is undergoing rapid changes: in other words, exposure to bacterial pathogens like S. pneumoniae in the first weeks of life may result in a different immunological response than first exposure when a child is a few months old and the immune system has further developed. It remains to be determined whether early and dense pneumococcal colonisation of the URT, as experienced by infants in high endemicity settings like PNG, results in priming of protective immune responses, or alternatively leads to immune tolerance and consequent increased risk of persistent colonisation and disease.

PspA is a conserved protein that is expressed by virtually all S. pneumoniae strains; however, the protein shows structural diversity between pneumococcal strains and has been classified into 3 families based on sequence variability of the N-terminal domain of PspA. Although pneumococcal strains expressing family 1 or 2 PspA proteins account for 98 % of clinical isolates, PspA-specific IgG antibodies binding to this highly variable region are family-dependent [24]. We have previously reported that maternal-derived PspA1- but not PspA2-specific antibodies were associated with a higher risk for pneumococcal colonisation in Papua New Guinean infants [4], indicating a possible difference in the frequency of PspA1 versus PspA2 expressing pneumococcal strains circulating in this population, or functional differences between these family-specific antibodies.

The aims of this study were to examine the development of naturally acquired IgG antibodies to PspA families 1 and 2 (PspA1 and PspA2) in the first 18 months of life in a cohort of Papua New Guinean infants and to determine the association between early pneumococcal carriage and antibody responses to these proteins. We hypothesise that, due to the high pneumococcal exposure and early URT carriage experienced in our study population, there will be high naturally acquired IgG responses to the PspA proteins at a young age and that these can protect against subsequent carriage.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

This cohort study was conducted in the Asaro Valley in the Eastern Highlands province of PNG, of which Goroka town is the provincial capital. The PNG Institute of Medical Research (PNGIMR) headquarters, laboratories, and small clinic are located next to Goroka General Hospital, the only tertiary hospital in the province.

The children included in the analysis presented here were participants in a neonatal PCV trial that was conducted between 2005 and 2009. A detailed study protocol is published in Phuanukoonnon et al. [25]. In summary, between May 2005 and September 2007 pregnant women were recruited at Goroka General Hospital antenatal clinic and in villages located within an hour’s drive of Goroka town. Inclusion criteria for enrolment of newborns were the intention to remain in the study area for at least 2 years, a birth weight >2000 g, no acute neonatal infection, and no severe congenital abnormality. Children of mothers known to be human immunodeficiency virus positive were excluded. A total of 318 newborns were enrolled, of whom 104 were randomised to receive Prevenar® (PCV7, which includes the serotypes 4, 6B, 9 V, 14, 18C, 19 F, and 23 F) at birth, 1 and 2 months of age (neonatal group); 105 to receive PCV7 at 1, 2, and 3 months of age (the infant group); and 109 were randomised to the control group, not receiving PCV7. All children received their recommended childhood vaccines according to the Papua New Guinean immunisation schedule including Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine at birth; oral polio vaccine at birth, 1, 2, and 3 months; Hepatitis B vaccine at birth, 1, and 3 months; a combined Haemophilus influenzae type b, diphtheria, tetanus, whole cell pertussis vaccine at 1, 2, and 3 months; and a measles vaccine at 6 and 9 months. As part of the trial, at the age of 9 months, all children received a dose of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) (Pneumovax23®; Merck & Co, USA) containing serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7 F, 8, 9 N, 9 V, 10A, 11A, 12 F, 14, 15B, 17 F, 18C, 19 F, 19A, 20, 22 F, 23 F, and 33. Study infants were followed for 18 months after birth, in which period there were 10 prescheduled trial visits. In addition, village reporters conducted weekly surveillance of study participants in rural areas throughout the first year of life and then fortnightly to age 18 months.

A requirement for children to be included in the current analysis on the development of IgG antibodies to PspA1 and PspA2 in relation to carriage was a complete set of plasma samples and pernasal swabs at 3, 9, and 18 months of age. Due to financial constraints, PspA-specific antibodies were assessed for only 88 children. Selection was based on the sequential ID numbers of children with complete datasets: of these 88 children, 23 children had been randomised to the neonatal PCV7 group, 38 to the infant PCV7 group, and 27 to the control group.

Bacteriology of pernasal swabs

Standardised methodologies as described previously [26] were used for collection, transportation, and storage of the pernasal swabs and subsequent culturing, identification, and isolation of S. pneumoniae [26–28]. Briefly, pernasal swabs were stored in 1 ml of skim milk-glucose-glycerol broth (SMGGB) at -70 °C until further processing at PNGIMR. After thawing and vortexing, 10 μl aliquots of the pernasal swabs in SMGGB were streaked onto horse blood agar, chocolate agar, gentamicin blood agar (5 μg/ml), and bacitracin chocolate agar (300 μg/ml). Plates were incubated overnight (18–24 h) at 37 °C in 5 % CO2-enriched atmosphere. Presumptive pneumococcal colonies were then cultured with an optochin disc and confirmed to be S. pneumoniae based on their susceptibility.

Detection and quantification of PspA-specific IgG using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

As described previously [4, 25, 29], venous blood samples were collected in sterile tubes containing 100 International Units of preservative-free heparin to allow the collection and separation of peripheral mononuclear cells and plasma. Samples were spun within 2 h of collection for 10 min at 700 × g. Plasma samples were aliquoted and stored at -20 °C until they were analysed.

PspA1 (family 1, clade 2) antigen was derived from the recombinant Rx1AA1.0.302 protein, and PspA2 (family 2, clade 3) from PspA/V-24AA1.0.410. A detailed description on the methodology for the expression and purification of these recombinant antigens is described in Francis et al. [4].

Minor changes were made to a previously established ELISA for the detection and quantification of PspA-specific IgG plasma antibodies [4], including using coating concentrations of 1 μg/ml and 0.5 μg/ml for PspA1 and PspA2, respectively, and using the new human anti-pneumococcal capsule reference standard 007sp (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [NIBSC], UK). The reference standard was serially diluted (two-fold) using a starting dilution of 1/200 for PspA1 and 1/400 for PspA2. In addition, high and low quality control plasma standards (taken from PNGIMR laboratory volunteers) were diluted at single dilutions of 1/400 and 1/1600, respectively, for both PspA antigens, and test samples were serially diluted (two-fold) using a starting dilution of 1/200.

Statistical analyses

Since PspA1- and PspA2-specific IgG antibody levels were not normally distributed, analyses were performed on log-transformed data. Paired t-tests were used to investigate the changes in PspA1 and PspA2 antibody concentrations between time points. Differences in geometric mean concentrations (GMC) of PspA1- and PspA2-specific IgG between pneumococcal carriers and non-carriers at each time point were examined using independent samples t-tests with the unequal variance assumption. To confirm these differences after accounting for potential confounding by the vaccine group, linear regression models were run with log concentration as the dependent variable and vaccine group membership was included as a covariate. Microsoft Excel version 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, USA) was used for data management and generation of graphical presentations. Statistical analyses were done using the statistical software package Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, USA). Antibody titres are expressed in arbitrary ELISA units (AU/ml).

Results

PspA1- and PspA2-specific antibody responses in relation to age

Of the 88 children included in this analysis, 53 were males and 35 were females; 23 were randomised to receive the neonatal PCV7 schedule, 38 received the infant PCV7 schedule, and 27 received no PCV7. As illustrated in Fig. 1a and b, PspA1- and PspA2-specific IgG responses decreased between 3 and 9 months of age (PspA1, p < 0.001; PspA2, p < 0.001) and then increased between 9 and 18 months of age (PspA1, p < 0.001; PspA2, p < 0.001).

PspA1- and PspA2-specific antibody responses in relation to age and URT carriage

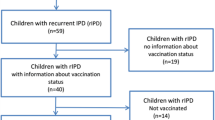

Pneumococcal carriage rates were 73, 85, and 83 % at 3, 9, and 18 months of age, respectively. All children carried S. pneumoniae at least once by the age of 18 months. PspA family-specific IgG levels were compared between pneumococcal carriers and non-carriers at the corresponding time points. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, at 3 months of age significantly lower PspA1-IgG levels were found in the pneumococcal carrier group (GMC 602 AU/ml, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 497–728) than in the non-carrier group (GMC 1058 AU/ml [95 % CI 732–1530]; p = 0.008). For PspA2-specific IgG responses (Fig. 2b), differences were not significant at age 3 months although responses tended to be higher in non-carriers (GMC 833 AU/ml, 95 % CI 565–1229) than in pneumococcal carriers (GMC 606 AU/ml [95 % CI 509–721]; p = 0.127). Conversely, at 9 months of age significantly higher PspA1-IgG responses were found in pneumococcal carriers (GMC 186 AU/ml, 95 % CI 136–256) than in non-carriers (GMC 87 AU/ml [95 % CI 45–169]; p = 0.037). IgG responses against PspA2 were also significantly higher in pneumococcal carriers (GMC 284 AU/ml, 95 % CI 192–421) than in non-carriers (GMC 74 AU/ml [95 % CI 34–159]; p = 0.003) at 9 months. No significant differences in PspA1-specific IgG responses were observed at 18 months of age between children who carried S. pneumoniae (GMC 477 AU/ml, 95 % CI 342–664) or those who did not carry (GMC 618 AU/ml [95 % CI 296–1291]; p = 0.503); the same was true for PspA2-specific IgG responses in the carriers (GMC 683 AU/ml, 95 % CI 491–949) and non-carriers (GMC 377 AU/ml [95 % CI 137–1041]; p = 0.250).

Geometric mean concentrations (GMC) of IgG responses to PspA1 (a) and PspA2 (b) in non-carrier (grey bars) and Streptococcus pneumoniae carrier (black bars) infants at 3, 9, and 18 months of age. Error bars indicate 95 % confidence intervals of the GMC. ✩ p ≤ 0.05 is considered a statistically significant difference. PspA, pneumococcal surface protein A; AU/ml, arbitrary ELISA units/ml

Linear regression models were run for each of the above comparisons with adjustment for vaccine group. Adjusted effect sizes were similar to unadjusted in all cases and significance levels relative to p = 0.05 remained unchanged (results not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge this study is the first to examine the natural development of circulating PspA family-specific IgG antibodies in association with age and URT pneumococcal carriage in a high-risk infant population. There were high levels of antibodies at the age of 3 months (most likely due to the presence of maternally derived antibodies) that waned by the age of 9 months. Levels then rose between 9 and 18 months of age, most likely as a result of natural pneumococcal exposure and development of the child’s own immunity.

In a longitudinal study in the Philippines, Holmlund et al. [19] examined natural antibody development to the PspA family 1 protein and the effect of pneumococcal carriage on antibody development in infants aged 6 weeks to 10 months. Children were classified as carriers from the time of first acquisition of S. pneumoniae. In this moderate-risk setting, maternally derived PspA1 antibody levels were found to decline to a low at age 20 weeks, followed by a modest increase in circulating antibody to PspA1, which tended to be higher in children who were prior pneumococcal carriers. In our study in the high-risk setting of PNG all children are colonised at least once by the age of 1 month, often with multiple pneumococcal serotypes; a prospective analysis as conducted in the Filipino study [19] is therefore not feasible. The higher PspA-IgG levels we found in non-carrier infants compared to the carrier infants at 3 months of age suggest that maternally derived antibodies may be protective and prevent or clear URT carriage. These high anti-PspA IgG titres early in life already show the potential activity of the protein if given in the form of a maternal vaccination. The higher IgG responses to both PspA1 and PspA2 in the pneumococcal carriers compared to non-carriers at 9 months of age (when maternal antibody has decayed) suggest that infants at this age can generate a good immune response to high levels of pneumococcal exposure. The high antibody titres seen in the pneumococcal carriers in this study cohort at 9 months old may indicate immune priming, but by age 18 months there were no significant differences in antibody titres against both PspA families between pneumococcal carriers and non-carriers. The universal acquisition of the pneumococcus by all Papua New Guinean infants by the age of 18 months is likely to have stimulated the immune response in all children, including the 17 % in whom the pneumococcus was not detected at age 18 months. We suggest that the observed association with pneumococcal carriage as well as the anticipated difference in immune maturation between individuals at 9 months of age can explain the larger variation in PspA-IgG concentrations that we found at this age as compared to when children were younger and responses were dominated by maternal antibodies and when older when their history of exposure and state of immune maturation may be less variable.

Papua New Guinean highland infants continue to experience a high prevalence of carriage, with 73 % of infants already carrying S. pneumoniae in their noses by 3 months of age. While we looked at carriage status and PspA antibody response levels in relation to vaccination (because two-thirds of the children in the study had received 3 doses of PCV7), no differences were found, supporting earlier reports from PNG [30] and other high-risk populations [31] that conjugate vaccination has little effect on overall pneumococcal carriage in high-risk populations.

This study has its limitations. Firstly, the sample size of this study is relatively small and there were only 3 sampling points, which limits the power of the study. Another limitation is that we did not assess bacterial load by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Instead of preventing carriage, it is possible that antibodies acquired to adhesins such as PspA reduce the density of pneumococcal carriage and subsequent risk of invasive disease. To date, financial constraints have precluded (semi) quantitative PCR on any of the nasopharyngeal samples collected as part of our trial. Finally, this study was not designed to determine immune hyporesponsiveness following PPV. However, hyporesponsiveness is unlikely to occur to a protein antigen following PPV vaccination. Despite its limitations, this study does contribute to the existing literature on naturally acquired antibody responses to PspA and their relationship to pneumococcal carriage by providing novel data for children who, with a median age of acquisition of 19 days, represent a population with the earliest documented onset of pneumococcal carriage. Yet, additional studies examining the relationship between development of PspA antibody responses, pneumococcal carriage (including load) and disease are needed in low- and high-risk populations to better understand the immune potential of this virulence antigen.

Conclusion

High and persistent URT S. pneumoniae carriage remains a burden and predisposing factor for early acquisition of pneumococcal diseases in Papua New Guinean children. The development of naturally acquired IgG antibodies against PspA increases with age as a result of active URT carriage exposure. The protective role of naturally acquired immunity to PspA against pneumococcal disease is not clear. Administering a pneumococcal protein-based vaccine containing multiple pneumococcal proteins including potentially PspA1/2 as a complementary vaccine to currently available PCV to offer universal serotype-independent protection against early pneumococcal carriage and disease, may improve vaccine-induced prevention of pneumococcal disease in high-risk populations.

References

Izadnegahdar R, Cohen AL, Klugman KP, Qazi SA. Childhood pneumonia in developing countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:574–84. PMID:24461618, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70075–4.

Zar HJ, Ferkol TW. The global burden of respiratory disease-impact on child health. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:430–4. PMID:24610581, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23030.

Sa’avu M, Duke T, Matai S. Improving paediatric and neonatal care in rural district hospitals in the highlands of Papua New Guinea: a quality improvement approach. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2014;34:75–83. PMID:24621233, http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/2046905513Y.0000000081.

Francis JP, Richmond PC, Pomat WS, Michael A, Keno H, Phuanukoonnon S, et al. Maternal antibodies to pneumolysin but not to pneumococcal surface protein A delay early pneumococcal carriage in high-risk Papua New Guinean infants. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:1633–8. PMID:19776196, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00247-09.

Leach AJ, Boswell JB, Asche V, Nienhuys TG, Mathews JD. Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx predicts very early onset and persistence of otitis media in Australian aboriginal infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:983–9. PMID:7845752, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199411000-00009.

Feikin DR, Kagucia EW, Loo JD, Link-Gelles R, Puhan MA, Cherian T, Serotype Replacement Study Group, et al. Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001517. PMID:24086113, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001517.

Hammitt LL, Akech DO, Morpeth SC, Karani A, Kihuha N, Nyongesa S, et al. Population effect of 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae in Kilifi, Kenya: findings from cross-sectional carriage studies. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e397–405. PMID:25103393, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70224–4.

Hammitt LL, Ojal J, Bashraheil M, Morpeth SC, Karani A, Habib A, et al. Immunogenicity, impact on carriage and reactogenicity of 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine in Kenyan children aged 1-4 years: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85459. PMID:24465570, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085459.

Henriques-Normark B, Blomberg C, Dagerhamn J, Bättig P, Normark S. The rise and fall of bacterial clones: Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:827–37. PMID:18923410, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2011.

Pittet LF, Posfay-Barbe KM. Pneumococcal vaccines for children: a global public health priority. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 Suppl 5:25–36. PMID:22862432, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03938.x.

Prescott SL, Taylor A, King B, Dunstan J, Upham JW, Thornton CA, et al. Neonatal interleukin-12 capacity is associated with variations in allergen-specific immune responses in the neonatal and postnatal periods. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:566–72. PMID:12752583, http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01659.x.

Ren B, McCrory MA, Pass C, Bullard DC, Ballantyne CM, Xu Y, et al. The virulence function of Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein A involves inhibition of complement activation and impairment of complement receptor-mediated protection. J Immunol. 2004;173:7506–12. PMID:15585877, http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7506.

Ren B, Szalai AJ, Thomas O, Hollingshead SK, Briles DE. Both family 1 and family 2 PspA proteins can inhibit complement deposition and confer virulence to a capsular serotype 3 strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2003;71:75–85. PMID:12496151, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.71.1.75-85.2003.

Briles DE, Hollingshead SK, Paton JC, Ades EW, Novak L, van Ginkel FW, et al. Immunizations with pneumococcal surface protein A and pneumolysin are protective against pneumonia in a murine model of pulmonary infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:339–48. PMID:12870114, http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/376571.

Miyaji EN, Dias WO, Gamberini M, Gebara VC, Schenkman RP, Wild J, et al. PsaA (pneumococcal surface adhesin A) and PspA (pneumococcal surface protein A) DNA vaccines induce humoral and cellular immune responses against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine. 2001;20:805–12. PMID:11738744, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00395–4.

Ogunniyi AD, Grabowicz M, Briles DE, Cook J, Paton JC. Development of a vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease based on combinations of virulence proteins of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2007;75:350–7. PMID:17088353, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01103-06.

Palaniappan R, Singh S, Singh UP, Sakthivel SK, Ades EW, Briles DE, et al. Differential PsaA-, PspA-, PspC-, and PdB-specific immune responses in a mouse model of pneumococcal carriage. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1006–13. PMID:15664944, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.73.2.1006-1013.2005.

Hales BJ, Chai LY, Elliot CE, Pearce LJ, Zhang G, Heinrich TK, et al. Antibacterial antibody responses associated with the development of asthma in house dust mite-sensitised and non-sensitised children. Thorax. 2012;67:321–7. PMID:22106019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200650.

Holmlund E, Quiambao B, Ollgren J, Nohynek H, Käyhty H. Development of natural antibodies to pneumococcal surface protein A, pneumococcal surface adhesin A and pneumolysin in Filipino pregnant women and their infants in relation to pneumococcal carriage. Vaccine. 2006;24:57–65. PMID:16115703, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.055.

Melin MM, Hollingshead SK, Briles DE, Lahdenkari MI, Kilpi TM, Käyhty HM. Development of antibodies to PspA families 1 and 2 in children after exposure to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1529–35. PMID:18753341, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00181-08.

Simell B, Melin M, Lahdenkari M, Briles DE, Hollingshead SK, Kilpi TM, et al. Antibodies to pneumococcal surface protein A families 1 and 2 in serum and saliva of children and the risk of pneumococcal acute otitis media. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1528–36. PMID:18008233, http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/522607.

Laine C, Mwangi T, Thompson CM, Obiero J, Lipsitch M, Scott JA. Age-specific immunoglobulin g (IgG) and IgA to pneumococcal protein antigens in a population in coastal Kenya. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3331–5. PMID:15155637, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.72.6.3331-3335.2004.

Turner P, Turner C, Green N, Ashton L, Lwe E, Jankhot A, et al. Serum antibody responses to pneumococcal colonization in the first 2 years of life: results from an SE Asian longitudinal cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E551–8. PMID:24255996, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12286.

Darrieux M, Miyaji EN, Ferreira DM, Lopes LM, Lopes AP, Ren B, et al. Fusion proteins containing family 1 and family 2 PspA fragments elicit protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae that correlates with antibody-mediated enhancement of complement deposition. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5930–8. PMID:17923518, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00940-07.

Phuanukoonnon S, Reeder JC, Pomat WS, Van den Biggelaar AH, Holt PG, Saleu G, Neonatal Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Trial Study Team, et al. A neonatal pneumococcal conjugate vaccine trial in Papua New Guinea: study population, methods and operational challenges. P N G Med J. 2010;53:191–206. PMID:23163191.

O’Brien KL, Nohynek H, World Health Organization Pneumococcal Vaccine Trials Carriage Working Group. Report from a WHO working group: standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:133–40. PMID:12586977, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000048676.93549.d1.

Gratten M, Montgomery J. The bacteriology of acute pneumonia and meningitis in children in Papua New Guinea: assumptions, facts and technical strategies. P N G Med J. 1991;34:185–98. PMID:1750263.

Montgomery JM, Lehmann D, Smith T, Michael A, Joseph B, Lupiwa T, et al. Bacterial colonization of the upper respiratory tract and its association with acute lower respiratory tract infections in Highland children of Papua New Guinea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12 Suppl 8:S1006–16. PMID:2270397, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/12.Supplement_8.S1006.

Pomat WS, van den Biggelaar AH, Phuanukoonnon S, Francis J, Jacoby P, Siba PM, Neonatal Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Trial Study Team, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of neonatal pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in Papua New Guinean children: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56698. PMID:23451070 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056698.

Aho C, Greenhill A, Phuanukoonnon S, Michael A, Moberly S, Pomat W, et al. Impact of neonatal and early infant pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on pneumococcal carriage and suppurative otitis media in Papua New Guinea. Tel Aviv: Seventh International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases (ISPPD 7); 2010.

Keck JW, Wenger JD, Bruden DL, Rudolph KM, Hurlburt DA, Hennessy TW, et al. PCV7-induced changes in pneumococcal carriage and invasive disease burden in Alaskan children. Vaccine. 2014;32:6478–84. PMID:25269095, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.037.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to the children and their families who participated in the study. Institutions and investigators comprising the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Trial Study Team are: Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research: E. Aemamero, M. Akunaii, H. Aole, E. Bilam, M. Dreyam, S. Eza’e, J. Francis, N. Fufu, E. Hasu, L. Helivi, G. Inapero, T. Jack, S. James, A. Javati, H. Keno, W. Kirarock, I. Ko’ezo, M. Lai, A. Lapiso, A.M. Laumaea, S. Maraga, M. Martin, A. Michael, M. Michaels, A. Mope, P. Namuigi, B. Nivio, P. Ove, C. Opa, T. Orami, N. Paul, S. Phuanukooonnon, G. Poigeno, W.S. Pomat, J. Reeder (also Burnet Institute), G. Saleu, R. Sehuko, P. Siba, V. Siba, A. Sie, L. Sinke, J. Totave, B. Uro, G. Vengiau, L. Wawa’e, T. Wayaki, M. Yoannes; Goroka General Hospital: Doctors J. Ande, J. Apa, D. Frank, W. Pame, P. Keasu, A. Pikuri, H. Pok; Telethon Kids Institute (formerly Institute for Child Health Research): K.S. Alpers, C. Devitt, P.G. Holt, P. Jacoby, I. Laing, D. Lehmann, M. Nadal-Sims, A.H.J. van den Biggelaar; University of Western Australia: P.C. Richmond; PathWest Laboratory Medicine WA: G. Chidlow, J. Harnett, D.W. Smith; Curtin University: M.P. Alpers; Menzies School of Health Research: A.J. Leach. We also thank Dr Andrew Greenhill (PNGIMR and Federation University, Victoria, Australia) and Dr Rebecca Ford (PNGIMR, Papua New Guinea) for their microbiological advice and support.

Funding

The Neonatal Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination trial was funded by an International Collaborative Project Grant of the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom) (071613/Z/03/Z) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC 303123). The serological analysis reported here was supported by an Internal Competitive Research Award Scheme Small Grant (271/F) from the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research. The funder had no role in study design, collection and analysis of data, decision to publish, or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors met ICMJE authorship criteria. JF, WP, PR, DL, PS conceived and designed the experiments. WT, BH constructed and provided the protein antigens. AM conducted the bacteriology. PJ provided statistical support. JF collected the data under supervision of WP and PS. JF, AM, AvdB conducted the data analysis and interpretation. JF wrote the first draft of the manuscript and final version with support from AvdB. AM contributed to the early drafts of the manuscript. PR, PS, PJ, BH, WT, DL, WP, AvdB critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. JF, PR, PS, PJ, BH, WT, DL, WP, AvdB agree with the manuscript’s results and conclusions. JF, PR, PS, PJ, BH, WT, DL, WP, AvdB approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PR has been a member of vaccine advisory boards for Wyeth and CSL Ltd and has received institutional funding for investigator-initiated research from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Merck and received travel support from Pfizer and Baxter to present study data at international meetings. DL has been a member of the GSK Australia Pneumococcal-Haemophilus influenzae-Protein D conjugate vaccine (“Synflorix”) Advisory Panel, has received support from Pfizer Australia and GSK Australia to attend conferences, has received an honorarium from Merck Vaccines to give a seminar at their offices in Pennsylvania and to attend a conference, and is an investigator on an investigator-initiated research grant funded by Pfizer Australia. WP has received funding from Pfizer Australia to attend a conference. AvdB has received support from Pfizer Australia and GSK Australia to attend conferences and received a Pfizer-supported Robert Austrian Award in Pneumococcal Vaccinology (2008); she was previously an employee of Crucell/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson and Johnson, The Netherlands. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the PNGIMR Institutional Review Board, the Medical Research Advisory Committee of Papua New Guinea (MRAC 03/20) and the Princess Margaret Hospital Ethics Committee in Perth, Australia (1083/EP). The Neonatal PCV Trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT00219401).

Assent was sought from women and their partners at the time of recruitment. Written informed consent was obtained after delivery and before enrolment of the newborn children.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Audrey Michael deceased.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Francis, J.P., Richmond, P.C., Michael, A. et al. A longitudinal study of natural antibody development to pneumococcal surface protein A families 1 and 2 in Papua New Guinean Highland children: a cohort study. pneumonia 8, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-016-0014-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-016-0014-x