Abstract

This study explores the relations between the different parts of headquarters (HQ) to which subsidiaries report and the knowledge-sharing patterns of subsidiaries in multinational corporations (MNCs). Despite the growing interest in the disaggregation of HQ, little is known about how subsidiaries’ reporting relationships with different parts of HQ are associated with the knowledge-sharing patterns of subsidiaries. Based on this motivation, we disaggregated HQ into different parts, i.e., corporate R&D HQ, top management, divisional HQ, and regional HQ, and explored how knowledge-sharing patterns of overseas R&D subsidiaries vary according to the different parts of the HQ to which they report. We found that subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ show the highest level of external knowledge sharing (EKS), while those reporting to divisional HQ show the lowest level; in addition, subsidiaries reporting to top management show the highest level of internal knowledge sharing (IKS), while those reporting to regional HQ show the lowest level. The study implies that the knowledge-sharing patterns of overseas R&D subsidiaries in MNCs cannot be fully understood without examining the subsidiaries’ reporting relationships with differing parts of the HQ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study explores the association between different parts of headquarters (HQ) to which subsidiaries report and the knowledge sharing of subsidiaries in multinational corporations (MNCs). More specifically, we investigate how the different parts of HQ at the corporate and divisional/regional levels to which overseas subsidiaries report are related to the knowledge-sharing patterns of overseas subsidiaries. While extant studies in the field of international business have identified various determinants of global knowledge sourcing and sharing by overseas subsidiaries, we know little about the way subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing is associated with the different parts of the HQ to which overseas subsidiaries report. For example, extant studies have suggested the way in which subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing is affected by the following factors: the external embeddedness of subsidiaries (Andersson et al. 2001, 2002; Song et al. 2011), the competence-creating mandates of subsidiaries (Cantwell and Mudambi 2005), the capability of the parent firm (Song and Shin 2008), the capability of the subsidiary (Frost 2001; Song et al. 2011), the managerial capability of mobilizing globally dispersed knowledge (Doz et al. 2001), and the role of overseas scouting units (Monteiro and Birkinshaw 2017); however, studies have dedicated rather limited attention to the role of HQ.

More recently, the literature has highlighted the role of HQ in subsidiaries’ innovation (Nell and Ambos 2013; Dellestrand and Kappen 2011, 2012; Ciabuschi et al., 2011c). Research on the role of HQ adding value in subsidiary innovation has been conducted extensively from the perspectives of corporate parenting (Goold and Campbell 2002; Nell and Ambos 2013), HQ attention (Ambos and Birkinshaw 2010; Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008), and the promotion of horizontal linkages among subsidiaries (Ciabuschi et al., 2011b; Dellestrand and Kappen 2011), among others.

Despite such prior research endeavors on HQ contributions to subsidiary innovation, this body of research in the field of international business has largely neglected the complexities of HQ by treating it as a single entity (Decreton et al. 2017; Nell et al. 2017). Drawing on insights from the field of corporate strategy, only recently have scholars started highlighting this complexity and offering more fine-grained insights into the role of different parts of HQ (Ciabuschi et al. 2012; Kunisch et al. 2019; Nell et al. 2017). Recent studies have identified the role of multiple parts of HQ (Nell et al. 2017; Kunisch et al. 2019; Hoenen and Kostova 2015), which include corporate and other levels of HQ. Furthermore, the simultaneous involvement of different parts of HQ is becoming increasingly common (Decreton et al. 2017; Birkinshaw et al. 2016). In addition, the geographic dispersion of the HQ function (Kunisch et al. 2019; Baaij et al. 2015) continues as regional units play an even more significant role in mobilizing knowledge across borders (Schotter et al. 2017; Mahnke et al. 2012; Alfondi et al. 2012). The relocation of HQ to overseas locations is also taking place (Birkinshaw et al. 2006; Baaij et al. 2015; Desai, 2009).

Nevertheless, despite the complexity and multiple parts of HQ involvement, patterns of knowledge sharing, i.e., the ways subsidiaries share knowledge vary across the different parts of the HQ to which the subsidiaries report, remain underexplored. Very few extant studies (Ciabuschi et al. 2012) examine the various impacts of the different parts of HQ at the corporate and divisional/regional levels to which subsidiaries report on their knowledge-based activities.

Based on this motivation, we examine how subsidiaries’ reporting relationships with different parts of HQ are related to the knowledge-sharing patterns of subsidiaries by focusing our attention on the research and development (R&D) function. We find the R&D function most relevant to explore this question, given its extensive level of external and internal knowledge sharing by subsidiaries for innovation. For this reason, we look at R&D subsidiaries’ knowledge-sharing patterns and their reporting relations with corporate and divisional/regional levels of HQ. In the context of R&D, R&D HQ plays the role of corporate HQ. Here, the R&D subsidiaries are those responsible for various types of R&D tasks, ranging from basic research to product modification. R&D subsidiaries engage in knowledge sharing with various parties that are internal and external to the firm, i.e., internally with HQ and other overseas subsidiaries and externally with local and overseas universities and businesses (Meyer et al. 2011; Ciabuschi et al. 2011a; Dellestrand and Kappen 2011; Asakawa et al. 2018).

This research contributes to the literature on the role of corporate HQ and knowledge sharing by MNC subsidiaries, by showing that the way overseas subsidiaries report to different levels and parts of HQ manifests differing knowledge-sharing patterns of subsidiaries. Moreover, we demonstrate how organization design in MNCs matters for the knowledge-sharing patterns of overseas subsidiaries of MNCs.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. After discussing the established views in the literature on the role of different parts of HQ in the knowledge-sharing patterns of subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ, the data and methods are summarized, followed by a presentation of the findings and conclusions.

Conceptual scope and logic

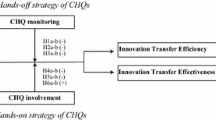

This section summarizes the conceptual scope and logic of our discussions presented in this paper. As illustrated in Fig. 1, since our focus is on the relations between the levels and parts of the HQ to which the subsidiaries report and the knowledge-sharing patterns of the subsidiaries, we first present the levels and parts of the HQ to which the subsidiaries report, and then we present knowledge-sharing patterns of the subsidiaries.

Reporting to different levels and parts of HQ

While the prior literature has predominantly regarded HQ as a single entity when knowledge sharing in MNCs is discussed, such a view does not help us determine the conditions under which the reporting relations of R&D subsidiaries are related to their knowledge-sharing patterns. More recent literature on the role of HQ suggests that HQ comprises different levels and parts (Baaji et al. 2015; Baaji and Slangen 2013; Collis et al. 2012; Desai 2009; Kunisch et al. 2014). The disaggregated parts of HQ are classified at different levels, i.e., corporate level and regional, divisional, and functional levels (Ciabuschi et al. 2012). When the corporate HQ of an MNC needs to cope with the high level of uncertainty and complexity of processing a wide range of information dispersed throughout the world, the corporate HQ often delegates the coordinating roles to regional or divisional HQs (Galbraith 1973; Egelhoff 1982, 1991). The corporate HQ also tries to cope with mounting transaction costs in dealing with diverse unfamiliar entities across geographic and business contexts by delegating the coordinating tasks to regional and divisional HQs (Decreton et al. 2017; Williamson 1975). Given the different nature of HQs at different levels, we infer that the nature of overseas subsidiaries may also vary according to the different levels of HQ to which they report.

Corporate HQ level

The corporate HQ continues to add value in the multimarket firm context (Menz et al. 2015) and the multinational business context. The extant literature identifies that a corporate HQ offers overseas subsidiaries parenting (Goold and Campbell 2002; Goold et al. 1998; Campbell et al. 1995; Poppo 2003; Nell and Ambos 2013), valuable knowledge (Nell et al. 2016), and connections with other subsidiaries (Ciabuschi et al., 2011b; Dellestrand and Kappen 2011, 2012). The corporate HQ coordinates activities across business divisions (Poppo 2003) and geographic locations (Dellestrand and Kappen 2011). The corporate HQ focuses on firm-wide incentives and control systems (Williamson 1975; Decreton et al. 2017). It also has superior knowledge that is valuable across business divisions (Martin and Eisenhardt 2010) and valuable knowledge about the opportunity to collaborate across business divisions (Decreton et al. 2017). Thus, subsidiaries seek to receive the attention of the corporate HQ (Ambos and Birkinshaw 2010; Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008) to fully leverage such benefits.

Prior research suggests that the corporate HQ comprises different parts, including the core staff functions of the corporate HQ, the members of the executive management teams, and the corporate legal seat (Baaji et al. 2015). Desai (2009) also specifies top management as an important component of corporate HQ along with the legal and financial components. In the specific context of R&D, which is our focus in this study, when an overseas R&D subsidiary reports to corporate-level HQ, its direct counterpart within corporate HQ is either corporate R&D HQ or top management (Asakawa 2001). Therefore, the corporate HQ level consists of the two parts: corporate R&D HQ and top management.

Corporate R&D HQ

This is the headquarters in charge of R&D located in the corporate HQ in the home country. While corporate R&D HQ is focused on the R&D function, it plays the role of a corporate HQ that supervises all R&D activities of a firm that are beyond the scope of a particular business division. The corporate R&D HQ is responsible for parenting overseas R&D subsidiaries by offering knowledge directly to the subsidiaries (Almeida and Phene 2004; Yamin and Andersson 2011), interacting vertically with the subsidiaries through the exchange of engineers (Song et al. 2003) and coordinating horizontally across subsidiaries (Dellestrand and Kappen 2011; Ciabuschi et al., 2011a; Poppo 2003; Decreton et al. 2017). R&D subsidiaries report to corporate R&D HQ for the most natural reason: They engage in R&D activities that are generally under the control of the corporate R&D HQ. The subsidiaries may also obtain knowledge and advice related to R&D from the HQ. While the corporate R&D HQ could be considered a functional unit, we position it as a corporate-level HQ in the R&D-specific context that supervises overseas R&D subsidiaries.Footnote 1

Top management

This is the team of top managers at the corporate HQ in the home country. Top management plays a flexible parenting role by providing overseas R&D subsidiaries with informal suggestions and encouragement, especially in the early start-up phase of subsidiary evolution (Asakawa 2001), but even after the subsidiaries develop and mature. As top management sets the dominant logic of a firm that serves as a basis of the firm’s fundamental norms and values (Hambrick and Mason 1984), the top management influences the strategic vision of the firm’s R&D activities. R&D subsidiaries report to top management, which provides subsidiaries with more overall visionary support going beyond the narrowly defined boundary of the R&D task.

Divisional and regional HQ level

Another level of HQ consists of divisional HQ and regional HQ. And these two parts represent the business and geographic dimensions, respectivelyFootnote 2 and they constitute the main components of matrix management (Galbraith 2009).

Divisional HQ

Since the divisional HQ directly engages in managing a business division, it prioritizes the performance of the division. The divisional HQ is the headquarters in charge of a business division located in the home country. In addition, it monitors and supervises activities and operations within a business division (Williamson 1975) rather than in the firm-level context. While the corporate HQ supervises firm-level performance and resource allocation and engages in long-term corporate strategy, the divisional HQ is more focused on overseeing and monitoring the concrete business operations and performance outcome within the division (Decreton et al. 2017). R&D subsidiaries report to divisional HQ when they engage in the more downstream stage of R&D tasks, such as developing and modifying products for a particular business division. Divisional HQ does not coordinate activities with other business divisions (Verbeke and Kenworthy 2008; Poppo 2003).

Regional HQ

This is the headquarters in charge of region-specific matters and is located in a region outside the home country. The regional HQ operates at the intermediate level of geographic scope, between the local and global levels (Lehrer and Asakawa 1999) and is in charge of coordinating operations within regions (Alfoldi et al. 2012; Mahnke et al. 2012; Schotter et al. 2017), as well as coordinating activities between the region and the corporate HQ (Mahnke et al. 2012; Schotter et al. 2017). R&D subsidiaries report to regional HQ when they engage in more region-specific R&D tasks, such as developing and modifying products for a particular geographic region, including the EU, North America, and Asia.

Knowledge-sharing patterns

Herein, we focus on knowledge-sharing patterns, i.e., the ways in which subsidiaries share knowledge externally and internally. Although knowledge sharing is supposedly more efficient within MNCs than in other settings (Kogut and Zander 1993), sharing tacit, implicit know-how (Kogut and Zander 1992) across cultural and institutional contexts is considered to be harder than sharing explicit information, which is less sticky and less contextually embedded (Kogut and Zander 1992; Szulanski 1996; Doz et al. 2001). Mobilizing the more tacit, contextual and sticky knowledge, however challenging it is, can be a source of global competitive advantage (Doz and Willson 2012). Since R&D involves tacit, complex knowledge, R&D subsidiaries may benefit from HQ assistance when trying to share such R&D-related knowledge. Moreover, as the patterns of knowledge sharing within MNCs are complex (Gupta and Govindarajan 1991, 2000; Bartlett and Ghoshal 1989; Hansen and Haas 2001; Haas and Hansen 2007), HQ may play an important role in facilitating knowledge sharing within MNCs (Dellestrand and Kappen 2011). In addition, HQ may benefit from knowledge sharing within MNCs (Ambos et al. 2006).

Along the lines of research by Meyer et al. (2011), Ciabuschi et al. (2011a), Dellestrand and Kappen (2011), and Asakawa et al. (2018), we examine how the different parts of the HQ to which subsidiaries report are related to the following dimensions: external knowledge sharing (EKS), i.e., R&D subsidiaries’ external knowledge sharing with universities and research ventures located in the host country, and internal knowledge sharing (IKS), i.e., R&D subsidiaries’ internal bidirectional knowledge sharing with other overseas subsidiaries. In particular, the uniqueness of this paper lies in our focus on the way the different parts of the HQ to which subsidiaries report are associated with R&D subsidiaries’ external knowledge sharing (EKS) and internal knowledge sharing (IKS).

Empirical exploration

Approach

The study explores differences among overseas R&D subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ—corporate R&D HQ, top management, divisional HQ, and regional HQ—in terms of external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS). Due to the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding about the specific association between subsidiaries’ external and internal knowledge sharing and their reporting relations with different parts of HQ, we chose not to test formal hypotheses. Instead, we adopted an exploratory approach to identify facts and general patterns in the data following the spirit of the fact-based approach (Hambrick 2007; Helfat 2007; Oxley et al. 2010; Menz and Barnbeck 2017; Collis et al. 2007).

More specifically, we conducted research in two steps. First, to explore potential differences among subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ—corporate R&D HQ, top management, divisional HQ, and regional HQ—in terms of external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS), we analyzed the results of correlations and a two-sample t test. In this way, we identified patterns of knowledge sharing of overseas R&D subsidiaries across different reporting relations with different parts of HQ.

Second, to corroborate and extend the insights from this step, we further explored the association between subsidiaries’ knowledge-sharing patterns and their reporting relations with different parts of HQ. We used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to estimate the relative association of the different parts of the HQ to which subsidiaries report with the subsidiaries’ knowledge-sharing activities. Following the method used by Ambos et al. (2006), which compares the relative effect of multiple independent variables vis-à-vis a baseline variable, the effect of the different parts of the HQ to which subsidiaries report was measured relative to the effect of reporting to corporate R&D HQ, which was the baseline for comparison.Footnote 3

The use of confirmatory factor analysis to compose each independent variable implied a potential concern of multicollinearity; thus, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) were checked for each model. The result was that all the VIFs remained within the limit, with the highest values of 1.567 (without interaction terms) and 3.192 (with interaction terms), which are far below the threshold of 10 (Hair et al. 1998). The results indicated that multicollinearity was not a problem in this study. Furthermore, although the concern of common method bias was minimal due to the use of dummy variables as the independent variables and a five-point interval scale as the dependent variable, Harman’s single factor test was conducted for all the models. The results show that (1) the variables were split into 6 factors, with an eigenvalue > 1.0 and the cumulative percentage of variance captured by the first factor being 15.378%, which is below 50%, for the model with external knowledge sharing (EKS) as a dependent variable, and (2) the variables were split into 5 factors, with an eigenvalue > 1.0 and the cumulative percentage of variance captured by the first factor being 14.283%, which is below 50%, for the model with internal knowledge sharing (IKS) as a dependent variable. Therefore, we concluded that common method bias was not an issue in this study (Scott and Bruce 1994; Podsakoff and Organ 1986).

Sample and variables

Sample

Our sample included the overseas R&D subsidiaries of Japanese MNCs located in various countries. The R&D subsidiaries were the subsidiaries responsible for various parts of R&D tasks, ranging from basic research to product modification. Data were obtained from the overseas R&D subsidiaries. The unit of analysis is a subsidiary within an MNC.

Based on Toyokeizai (2008), a database that publishes comprehensive data annually on the overseas operations of Japanese firms, overseas subsidiaries operating in the R&D field were selected. Since the Toyokeizai database is a comprehensive list of the overseas subsidiaries of Japanese MNCs, we first selected all the overseas subsidiaries engaging in R&D tasks. In total, 497 overseas R&D subsidiaries were identified, and questionnaires were sent to the head of each R&D subsidiary by mail and online in 2009. In total, 102 subsidiaries participated in our survey (with a response rate of 21%). These subsidiaries belonged to 46 firms. Non-response bias was checked regarding the subsidiaries’ location and industry. A chi-square test was nonsignificant at the p = 0.217 level regarding the proportion of overseas R&D subsidiaries located in North America, nonsignificant at the p = 0.464 level regarding the proportion of overseas R&D subsidiaries in the pharmaceutical/chemistry industry, nonsignificant at the p = 0.590 level regarding the proportion of overseas R&D subsidiaries in the electronics industry, and nonsignificant at the p = 0.431 level regarding the proportion of overseas R&D subsidiaries in the automobile industry. The results show no significant difference at the p < 0.05 level between the total sample and the respondent group and thus do not suggest a problem of non-response bias. Ultimately, the analysis was based on the 99 complete responses (for an effective response rate of 20%).

Of the overseas R&D subsidiaries considered, 34% were located in North America, 33% were located in Europe, and 33% were located in other areas. Regarding the industry, 15% of the R&D subsidiaries engaged in R&D in the chemical industry, 12% in the pharmaceutical industry, 2% in the steel industry, 10% in the machinery industry, 35% in the electronics and electric industry, 16% in the automotive industry, 7% in the precision machinery industry, 19% in the telecommunication industry, and 21% in other industries. The respondents were allowed to select multiple answers. Regarding the task, 28% mainly conducted basic research, 48% conducted applied research (including preclinical/clinical research), 49% engaged in innovative product development, 42% made local adaptations of existing products, 23% performed design work, 27% performed system development, and 47% conducted information gathering. The respondents were allowed to select multiple answers.

Regarding the subsidiaries’ reporting relations with HQ, 39 (37.1%) subsidiaries reported to corporate R&D HQ, 8 (7.6%) reported to top management, 32 (30.5%) reported to divisional HQ, and 20 (19%) reported to regional HQ. For the reporting relationships, each subsidiary selected only one part of the HQ to which it reported.Footnote 4 All corporate R&D HQs, top management, and divisional HQ are located in Japan, while regional HQ are located outside Japan.

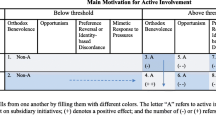

Variables

The factors are grouped into several dimensions following prior studies (Meyer et al. 2011; Ciabuschi et al., 2011a; Dellestrand and Kappen 2011; Asakawa et al. 2018). The dimensions, i.e., external knowledge sharing (EKS) and international knowledge sharing (IKS), are illustrated in Fig. 1. A confirmatory factor analysis of the variables related to external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS) was followed by a calculation of the subscale score of each factor taking the mean so that the scores would not be affected by the absolute number of items (cf. Santor et al. 2011). The measures of external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS), which were later used as dependent variables in the additional analysis, are presented in Table 1.

External knowledge sharing

The factor “external knowledge sharing” (EKS), defined as knowledge sharing with local universities and research ventures, consisted of four items: “implementing joint projects with local universities,” “recruiting researchers from the local universities,” “sending the researchers to the local universities,” and “collaborating with the research ventures.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.67, the average interitem correlation was 0.35, the eigenvalue was 2.12, and the cumulative percentage of variance explained was 34.6%. The construct was measured by a semantic differential (SD) interval scale from 1 = almost never to 5 = very frequent.

Internal knowledge sharing

The factor “Internal knowledge sharing” (IKS), defined as knowledge sharing with other overseas subsidiaries, consisted of three items: “the transfer of knowledge/technology from other overseas R&D subsidiaries within your firm to your R&D subsidiary,” “the transfer of knowledge/technology from your R&D subsidiary to other overseas R&D subsidiaries within your firm,” and “joint projects with other overseas R&D subsidiaries within your firm.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86, the average interitem correlation was 0.68, the eigenvalue was 3.01, and the cumulative percentage of variance explained was 46.33%. The construct was measured by an interval scale from 1 = almost never to 5 = very frequent.

These factors met the criteria for construct validity (converged in a single factor) and had an acceptable reliability index (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.60) (Howell 1987; Morrison 1976). For these items, the respondents were asked to answer considering the current conditions within the past few years.

The reporting relationship with different parts of HQ—corporate R&D HQ, top management, divisional HQ, and regional HQ—was a binary variable based on the questionnaire data. Since the respondents at the subsidiaries were asked to select one main part of the HQ to which they report, each option was mutually exclusive. Despite the current tendency for the multiple involvement of different parts of HQ (Decreton et al. 2017), we asked the respondents to choose one main HQ they reported to since our main objective was to identify the relative effect of each part of HQ on subsidiaries’ knowledge-sharing patterns.Footnote 5

For these items, the respondents were asked to answer regarding the existing reporting structure of their subsidiaries vis-à-vis the HQ in the past few years. The organizational position of overseas R&D subsidiaries as manifested in their reporting structure remains static for many years, often since their establishment, and is easily identifiable. We considered the existing reporting structure as a long-standing condition of subsidiaries that could be associated with the recent patterns of knowledge sharing by the subsidiaries. Since the current situation was explored in relation to the past few years, we tried to ensure the reliability of the retrospective report by asking for simple facts and concrete events and not asking about the distant past (Miller et al. 1997).

As shown in Table 2, dummy variables were created such that “Corporate R&D HQ” took a value of 1 if a subsidiary reported to corporate R&D HQ and 0 otherwise. “Top management” took a value of 1 if a subsidiary reported to the top management and 0 otherwise. “Divisional HQ” took a value of 1 if a subsidiary reported to divisional HQ and 0 otherwiseFootnote 6. “Regional HQ” took a value of 1 if a subsidiary reported to regional HQ and 0 otherwise. In the additional regression analysis, we set “Corporate R&D HQ” as the baseline and compared the relative impact of the other reporting relations relative to “Corporate R&D HQ,” following the method used by Ambos et al. (2006), in which a variable is used as a baseline for comparison with other variables to test the relative impact of a particular variable vis-à-vis the others.

“R Task” was a dummy variable that took a value of 1 if a subsidiary engaged in either basic research or applied research (i.e., “R task”) and 0 otherwise, with multiple choices allowed. Given that 53.9% of the overseas R&D subsidiaries (i.e., 55 out of 99 centers) engaged in the “R task”, no distribution bias was recognized among variables 1 and 0.

Table 2 lists the measures of the variables, which were later used as independent and control variables in the additional analysis.

Control variables

In the additional regression analysis, we controlled for the following variables as listed in Table 2.

An industry dummy was introduced (1 for pharmaceutical/chemical, 0 otherwise) (Saittakari 2018; Song et al. 2011) because external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS) through R&D collaboration and reporting relations with different parts of HQ are influenced by the type of industry. Science-driven, high-tech industries call for knowledge sharing, and subsidiaries in such industries are likely to report to the corporate R&D HQ rather than the divisional or regional HQ. We classified pharmaceutical/chemical industries as being more science-driven and high-tech than other industries (Song et al. 2011; Saittakari 2018; Asakawa et al. 2018).Footnote 7

Subsidiary age was measured by years in operation via natural logarithm (Decreton et al. 2017; Decreton et al. 2019).

Subsidiary size was measured by the number of R&D staff members, excluding the administrative staff (Decreton et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2019). The following interval scale was used: 1 (0~19 people), 2 (20~39 people), 3 (40~59 people), 4 (60~79 people), and 5 (80 or more people). Only the R&D staff members were counted because knowledge-sharing patterns are primarily affected by the R&D-related staff (Song et al. 2011).

A Western dummy (1 for North America and Europe, 0 otherwise) was created based on the assumption that the technological capability in Western countries is higher than that in other countries and that R&D subsidiaries located in Western countries are more likely to engage in R&D collaboration with local innovation clusters and knowledge sharing across borders (Frost 2001; Song and Shin 2008).

The R&D sales ratio and overseas sales ratio were firm-level data obtained from a separate survey with R&D HQ conducted by the author in 2009.

A single region dummy (1 for the parent company with single regional operations, 0 otherwise) was created because internal knowledge sharing (IKS), i.e., knowledge sharing with other foreign subsidiaries within a firm, is related to the geographic dispersion of R&D subsidiaries across borders.

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations of all the variables and factors used in the analysis. The appendix lists the questions asked in the survey.

Empirical insights

Step 1: descriptive insights

Based on the correlation matrix presented in Table 3, we identify the following significant relations between the parts of the HQ to which overseas R&D subsidiaries report and the knowledge-sharing patterns. Regarding external knowledge sharing (EKS), reporting to corporate R&D HQ is the most positively correlated with external knowledge sharing (EKS) (correlation = 0.330 at p < 0.001), while reporting to divisional HQ is the most negatively correlated with external knowledge sharing (EKS) (correlation = − 0.369 at p < 0.001). Regarding internal knowledge sharing (IKS), reporting to top management is positively correlated with internal knowledge sharing (IKS) (correlation = 0.206 at p < 0.05), while reporting to regional HQ is negatively correlated with internal knowledge sharing (IKS) (correlation = − 0.187 at p < 0.10).

Consistent patterns were revealed in a two-sample t test, in which we compared the means of the external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS) of subsidiaries based on their reporting relations with different parts of HQ without controlling for various conditions. Table 4 shows the following significant differences. The mean level of external knowledge sharing (EKS) of subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ (the mean score = 2.5 based on a semantic differential interval scale from 1 = almost never to 5 = very frequent; the same applies to other cases below) is higher than that of subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ (the mean score = 1.66) at p < 0.01. The mean level of external knowledge sharing (EKS) of subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ (the mean score = 2.27) is higher than that of subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ (the mean score = 1.66) at the p < 0.01 level. The mean level of internal knowledge sharing (IKS) of subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ (the mean score = 2.52) is higher than that of subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ (mean score = 2.04) at p < 0.05. Furthermore, the mean level of internal knowledge sharing (IKS) of the subsidiaries reporting to top management (mean score = 3.13) is higher than that of subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ (mean score = 2.35) at the p < 0.10 level, and the mean level of internal knowledge sharing (IKS) of the subsidiaries reporting to top management (mean score = 3.13) is higher than that of those reporting to regional HQ (mean score = 2.04) at the p < 0.01 level).

Furthermore, Table 3 shows that external knowledge sharing (EKS) is positively correlated with “R task” (correlation = 0.355, p < 0.001 level), size (correlation = 0.201, p < 0.05 level), and the Western dummy (correlation = 0.2, p < 0.05 level). It also shows that internal knowledge sharing (IKS) is positively correlated with size (correlation = 0.195, p < 0.1 level). In addition, internal knowledge sharing (IKS) is negatively correlated with a single region dummy (correlation = − 0.246, p < 0.05 level).

More specifically, “R task” is positively correlated with external knowledge sharing (EKS) (correlation = 0.355 at p < 0.001), while it is not significantly correlated with internal knowledge sharing (IKS) (correlation = 0.05, n.s.). Regarding the correlations between “R task” and the four parts of HQ, “R task” is positively correlated with corporate R&D HQ (correlation = 0.305 at p < 0.01), while it is negatively correlated with divisional HQ (correlation = − 0.382 at p < 0.001). As Table 5 shows, 29 out of 39 subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ (74%) engage in an “R task,” and the ratio differs significantly from those reporting to other parts of HQ (χ2 = 9.215, at p < 0.01). In contrast, only 9 out of 32 subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ (28%) engage in an “R task,” and the ratio differs significantly from those reporting to other parts of HQ (χ2 = 14.409, at p < 0.001).Footnote 8 Table 5 summarizes some key characteristics of the overseas R&D subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ in terms of the mean scores, based on a 5-point Likert scale, of external knowledge sharing (EKS) and internal knowledge sharing (IKS), the number and percentage of the subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ, and the number and percentage of the subsidiaries engaging in the “R task.”

In summary, based on the descriptive results, we observe the following patterns.

First, we confirm that the reporting relations with different parts of HQ show different knowledge-sharing patterns of the overseas R&D subsidiaries. Figure 2 is a graphic representation of the differences among the subsidiaries reporting to four parts of HQ in terms of the two dimensions: external knowledge sharing (EKS) and internal knowledge sharing (IKS).

Reporting to corporate R&D HQ is most positively correlated at the significant level with external knowledge sharing (EKS), and is positively correlated while non-significant with internal knowledge sharing (IKS). Reporting to top management is most positively correlated at the significant level with internal knowledge sharing (IKS). Reporting to divisional HQ is most negatively correlated at the significant level with external knowledge sharing (EKS), and is negatively correlated while non-significant with internal knowledge sharing (IKS). Reporting to regional HQ is negatively correlated at the significant level with internal knowledge sharing (IKS).

Second, while the difference between the subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ and those reporting to top management is not statistically significant in terms of either the mean external knowledge sharing (EKS) score or the mean internal knowledge sharing (IKS) score, we find the following differences between corporate R&D HQ and top management: Reporting to corporate R&D HQ and reporting to top management are negatively correlated with each other at the significant level. Reporting to corporate R&D HQ is most positively correlated at the significant level with external knowledge sharing (EKS), whereas reporting to top management is most positively correlated at the significant level with internal knowledge sharing (IKS). Based on such descriptive results, we can put corporate R&D HQ and top management on the upper-right position in Fig. 2, divisional HQ on the lower-left position in Fig. 2, and regional HQ on the lower-right position in Fig. 2.

Third, it deserves to be highlighted that a notable difference exists between corporate R&D HQ and divisional HQ in terms of the “R task”: Reporting to corporate R&D HQ is most positively correlated at the significant level with “R task,” whereas reporting to divisional HQ is most negatively correlated at the significant level with “R task.”

Step 2: additional analysis

To corroborate and further explore the results by controlling for various conditions, additional regression analysis was conducted.

In the base model (model 1 and model 5), only the control variables are included. In model 2 and model 6, “R task” was added. In model 3 and model 7, with corporate R&D HQ as a baseline, independent variables are added. In the models 4a, 4b, 4c and models 8a, 8b, 8c, interaction terms are added. Furthermore, in models 3b and 7b, a more fine-grained difference among independent variables is presented by setting different baselines, i.e., divisional HQ for external knowledge sharing (EKS) and regional HQ for internal knowledge sharing (IKS). All the models show a good fit with the data. The regression results are summarized in Tables 6, 7, and 8.Footnote 9

Different parts of the HQ to which the overseas R&D subsidiaries report and external knowledge sharing

As model 3 shows, we find that subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ are least likely to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS), i.e., to share knowledge with local universities and research ventures (β = − 0.567, significant at p < 0.05), relative to the subsidiaries reporting to other parts of HQ, including corporate R&D HQ, top management, and regional HQ, with reporting to corporate R&D HQ as the baseline. Subsidiaries reporting to top management and regional HQ also seem to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS) less than those reporting to corporate R&D HQ, as the baseline, albeit at a nonsignificant level (β = − 0.443, nonsignificant (n.s.) for top management; β = − 0.126, n.s. for regional HQ). Here, the coefficients and signs indicate the relative effects of reporting to divisional HQ or regional HQ on external knowledge sharing (EKS), with reporting to corporate R&D HQ as the baseline. This pattern confirms the descriptive statistics presented above. The result is reported in model 3, and it is illustrated in Fig. 3a.

However, model 3, which takes corporate R&D HQ as a baseline, does not clearly indicate which other parts of HQ are more positively related to external knowledge sharing (EKS) than divisional HQ. Therefore, to show how other parts of HQ are more positively related to external knowledge sharing (EKS) than divisional HQ, model 3b in Table 8 reveals that the subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ (β = 0.567 at p < 0.05) are most likely to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS), followed by those reporting to regional HQ (β = 0.441 at p < 0.10) and those reporting to top management (β = 0.124, n.s.), with reporting to divisional HQ as the baseline. The result is consistent with the descriptive statistics presented above. The pattern is presented in model 3b, and it is illustrated in Fig. 4a.Footnote 10

Different parts of the HQ to which the overseas R&D subsidiaries report and internal knowledge sharing

We find that subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ are least likely to engage in internal knowledge sharing (IKS), i.e., to share knowledge with other subsidiaries within the firm (β = − 0.538, significant at p < 0.05), relative to the subsidiaries reporting to other parts of HQ, including corporate R&D HQ, top management, and divisional HQ, with reporting to corporate R&D HQ as the baseline. Subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ also seem to engage in internal knowledge sharing (IKS) to a lesser extent (β = − 0.084, n.s.) relative to those reporting to corporate R&D HQ as the baseline, albeit at a nonsignificant level. Subsidiaries reporting to top management seem to engage in internal knowledge sharing (IKS) more, relative to those reporting to corporate R&D HQ, as the baseline (β = 0.551, n.s.), albeit at a nonsignificant level. Here, the coefficients and signs indicate the relative effects of reporting to regional HQ or divisional HQ on internal knowledge sharing (IKS), with reporting to corporate R&D HQ as the baseline. These findings confirm the descriptive statistics presented above. The result is reported in model 7, and it is illustrated in Fig. 3b.

However, model 7, which takes corporate R&D HQ as the baseline, does not clearly indicate which other parts of HQ are more positively related to internal knowledge sharing (IKS) than regional HQ. Therefore, to show what other parts of HQ are more positively related to internal knowledge sharing (IKS) than regional HQ, model 7b in Table 8 reveals that the subsidiaries reporting to top management (β = 1.089 at p < 0.01) are most likely to engage in internal knowledge sharing (IKS), followed by those reporting to corporate R&D HQ (β = 0.538 at p < 0.05) and divisional HQ (β = 0.454, n.s.), with reporting to regional HQ as the baseline. The result is consistent with the descriptive statistics presented above. The pattern is presented in model 7b, and it is illustrated in Fig. 4b.Footnote 11

Interaction terms

Tables 6, 7, and 8 summarize the results with the interaction terms. Figures 3a, b and 4a, b illustrate the results graphically.

Regarding external knowledge sharing (EKS), our analysis shows that the negative effect of the reporting relation with regional HQ (β = − 0.126, n.s.), although nonsignificant in model 3, becomes positive and significant (coefficient of interaction term “R task” X regional HQ = 0.880; significant at p < 0.05) with the “R task” as a moderator, as shown in model 4c. In other words, the negative effect of reporting to regional HQ, which indicates the lesser degree of external knowledge sharing (EKS) for subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ relative to that of those reporting to corporate R&D HQ as the baseline, is alleviated and becomes positive and significant when the subsidiaries engage in an “R task.” This implies that the subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ engage in more active external knowledge sharing (EKS) when carrying out an “R task.” On the other hand, the negative effect of the reporting relation with divisional HQ is strong in model 3, (i.e., β = − 0.567, significant at p < 0.05), and the moderating effect of the “R task” on this negative effect is negative and significant in model 4b (coefficient of interaction term “R task” X divisional HQ = − 0.826; significant at p < 0.05). This implies that the subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ continue to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS) less actively, even when they engage in an “R task.”Footnote 12 These findings corroborate and extend our insights from the descriptive statistics. The result is reported in models 4a–c.

Regarding internal knowledge sharing (IKS), our analysis shows that the negative effect of reporting to regional HQ (β = − 0.538, significant at p < 0.05) becomes positive (coefficient of interaction term “R task” X regional HQ = 0.486; n.s.), although nonsignificant, with the “R task” as a moderator, as shown in model 8c. In other words, the negative effect of reporting to regional HQ, which indicates a lesser degree of internal knowledge sharing (IKS) for subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ relative to that of those reporting to other parts of HQ, with reporting to corporate R&D HQ as a baseline, is mildly alleviated and becomes positive, albeit nonsignificant, when subsidiaries engage in an “R task.” This implies that the subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ do not refrain as much from sharing knowledge with other subsidiaries when they engage in an “R task.” On the other hand, the effect of the reporting relation with divisional HQ on internal knowledge sharing (IKS) is negative and nonsignificant (β = − 0.084, n.s.) in model 7, and it remains negative and nonsignificant (β = − 0.402, n.s.), with the “R task” as a moderator, as shown in model 8b. This implies that the subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ continue to refrain from sharing knowledge with other subsidiaries, with reporting to corporate R&D HQ as a baseline, even when they engage in an “R task.” These findings corroborate and extend our insights from the descriptive statistics. The result is reported in models 8a–c.

Discussion and conclusion

This study explored how knowledge sharing patterns of overseas R&D subsidiaries are associated with different parts of the HQ to which the subsidiaries report. We first observed different patterns of knowledge sharing based on the descriptive statistics, and we then further explored these patterns by additional regression analysis by controlling for various conditions and by considering the moderating effect of “R task” on these associations. By disaggregating HQ into different levels and parts (Nell et al. 2017; Baaij and Slangen 2013; Schotter et al. 2017), we demonstrated how knowledge-sharing patterns of overseas R&D subsidiaries vary according to different levels and parts of the HQ to which they report. In this section, first, we interpret our key findings more systematically. Second, we explore how our results can advance research on global knowledge sharing and HQ disaggregation. We conclude this section with the limitations and contributions of this study.

Interpretations of the main results

First, we discuss the patterns of external knowledge sharing (EKS): Subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ are the least likely to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS) and that the subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ are the most likely to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS), followed by those reporting to regional HQ and those reporting to top management. We interpret the results as follows.

Corporate R&D HQ recognizes the value of the external collaborations between the overseas R&D subsidiaries and local universities to enhance the R&D performance of the subsidiaries because external collaborations bring new knowledge into the firm to foster innovation (Doz and Wilson 2012). Thus, subsidiaries reporting to the corporate R&D HQ are likely to engage in active R&D collaborations with local universities to explore new innovative ideas. Subsidiaries’ relations with corporate R&D HQ generally entail knowledge linkages, and such reporting relations are beneficial for subsidiaries’ knowledge sourcing from external partners (Asakawa et al. 2018).

In contrast, divisional HQ expects its R&D subsidiaries to generate more immediate division-focused results, such as developing new products or adapting the products to the local market to boost market share and profitability (Decreton et al. 2017). Such objectives should leave little room for R&D subsidiaries to explore new ideas by engaging in sharing knowledge with local universities. The divisional HQ tends to prioritize the performance of the business division while overlooking the potential opportunity in geographic areas. For example, in Matsushita (now Panasonic), which was well known for its impeccable multidivisional organizational structure in the 1980s, the divisional HQs once notoriously downplayed the potential of overseas subsidiaries to learn from the local market (Bartlett and Ghoshal 1989).

Subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS) more than those reporting to divisional HQ. The regional HQ is well connected to the regional community in which the local subsidiaries are well positioned to engage in sourcing knowledge from the external environment and transferring it to the regional HQ, which in turn transfers it to the corporate R&D HQ for global innovation (Asakawa and Lehrer 2003).Footnote 13 However, they do not share knowledge externally as much as those reporting to corporate R&D HQ, perhaps due to a lower proportion of those engaging in “R task.”

Second, we discuss the patterns of internal knowledge sharing (IKS): Subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ are least likely to engage in internal knowledge sharing (IKS) and that subsidiaries reporting to top management are most likely to engage in internal knowledge sharing (IKS), followed by those reporting to corporate R&D HQ and divisional HQ. We interpret such a tendency as follows.

Subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ seem to rely on the regional HQ as a knowledge broker among subsidiaries and thus are less inclined to share knowledge directly among themselves than subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ.Footnote 14 Especially when the primary role of subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ is not necessarily related to the “R task,” they share knowledge among one another through regional HQs if necessary rather than sharing knowledge directly with other subsidiaries within the region.

Since the divisional HQ coordinates activities across subsidiaries within a business division (Poppo 2003), subsidiaries reporting to the divisional HQ may obtain division-wide knowledge from the divisional HQ without sharing knowledge directly with other overseas subsidiaries.

In contrast, subsidiaries reporting to top management and corporate R&D HQ are more relaxed about sharing knowledge horizontally with other subsidiaries because both are corporate-level HQ that place emphasis on enhancing firm-level innovations. Top management plays a flexible parenting role and establishes the dominant logic of a firm that serves as a basis of the firm’s fundamental norms and values (Hambrick and Mason 1984), and overseas R&D subsidiaries directly reporting to top management seem to embody the strategic vision and to appreciate the value of sharing knowledge and ideas with other R&D subsidiaries within a firm. Furthermore, since top management as individuals are usually not R&D specialists, their “cognitive limitations” (Decreton et al. 2017) concerning state-of-the-art R&D knowledge may lead them to encourage overseas subsidiaries to share knowledge with other subsidiaries without relying on them. As R&D subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ tend to engage in the “R task” that require active knowledge sharing across organizational units, they are also ready to engage in active knowledge sharing with other R&D subsidiaries within a firm to source complementary knowledge.

Third, we discuss the subtle difference between corporate R&D HQ and top management to which overseas R&D subsidiaries report: Within the category of corporate-level HQ, at first glance, no significant difference was identified between reporting to corporate R&D HQ and reporting to top management in terms of the extent of subsidiary external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS). However, a closer observation reveals that they are different in regard to the relations with the divisional or regional level of HQ Subsidiaries reporting to top management tend to exhibit a higher level of internal knowledge sharing (IKS) than those reporting to regional HQ and to divisional HQ to some extent. However, those reporting to top management do not show a significantly higher level of external knowledge sharing (EKS) than those reporting to other parts of HQ. In contrast, subsidiaries reporting to corporate R&D HQ tend to engage in a higher level of external knowledge sharing (EKS) than those reporting to divisional HQ, and they tend to engage in a higher level of internal knowledge sharing (IKS) than those reporting to regional HQ. In sum, we recognize that those reporting to corporate R&D HQ show higher levels of both external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS), i.e., the highest level of EKS and the second highest level of IKS, while those reporting to top management show the highest level of IKS. Therefore, we confirm that corporate-level HQs are not monolithic. Moreover, this implies the need for paying attention to differences across parts of the firm even within the same level of HQ.

Fourth, we found that only external and internal knowledge sharing patterns of subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ are influenced by the “R task” of the subsidiaries, whereas those reporting to other parts of HQ are not influenced by the “R task” of the subsidiaries. While subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ tend to engage in external knowledge sharing (EKS) with local universities and research ventures less than those reporting to corporate R&D HQ, those engaging in an “R task” collaborate with local universities and research ventures more actively because basic and applied research calls for direct knowledge sharing to create knowledge (Allen et al. 1979). In addition, subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ refrain to a lesser extent from sharing knowledge with other subsidiaries within the firm (IKS) when they take on the “R task” because basic and applied research tends to require direct interaction among researchers without going through knowledge gatekeepers (Allen et al. 1979; Tushman and Katz 1980). These patterns imply that subsidiaries reporting to regional HQ are potentially well positioned to share knowledge both external and internal to the firm, given their good access to the external community within the region and to other subsidiaries within the region. Nevertheless, given the lower portion of the “R task” assigned to them, as shown in Table 5, they are not urged to engage in external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS). In turn, when they are assigned an “R task,” they engage in external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS) more actively by taking advantage of their access to universities/research ventures and other R&D subsidiaries within the firm.

Integrating the research on the subsidiary’s knowledge sharing with the research on HQ disaggregation

We discuss how our study can advance the research on global knowledge sharing and HQ disaggregation. This study helps to advance research on global knowledge sharing of subsidiaries by relating the knowledge sharing literature to organization design literature. In the field of international business, subsidiaries’ innovation and knowledge sharing are frequently discussed in the context of subsidiary embeddedness (Granovetter 1985; Uzzi 1996; Andersson et al. 2001). Embeddedness is a relationship that reflects the intensity of knowledge exchange and the extent to which resources between the parties in the dyad are adapted (Uzzi 1996; Song et al. 2011). While overseas subsidiaries are embedded in multiple entities external and internal to the firm (Nell and Ambos 2013; Meyer et al. 2011), extant research tends to focus on the effect of external embeddedness on the subsidiaries’ competency, performance, and innovation (Andersson et al. 2001, 2002), with much less focus on the effect of internal embeddedness. And such an effect remains less obvious, with potentially positive or negative impact on subsidiary’s innovation (Meyer et al. 2011; Mudambi 2011).

More recently, a number of studies feature the effect of internal embeddedness on the subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing and innovation. It was identified that HQ tends to have a good grasp of the locus of key knowledge the subsidiaries are trying to access (Dellestrand and Kappen 2011). HQ was identified as a knowledge broker fostering the knowledge linkages among the subsidiaries within the MNCs (Dellestrand and Kappen 2011). Asakawa et al. (2018) sheds light on the effect of internal embeddedness on the subsidiaries’ global knowledge sourcing, i.e., the impact of subsidiaries’ relations with HQ on subsidiaries’ knowledge sourcing. By classifying internal embeddedness into knowledge embeddedness and administrative embeddedness,Footnote 15 Asakawa et al. (2018) tested how different types of internal embeddedness vis-à-vis the HQ affects subsidiaries’ knowledge sourcing differently. However, such prior studies did not examine the effect of internal embeddedness by disaggregating the HQ into different parts. Our study extends this line of research by further disaggregating HQ into different parts to show how subsidiaries’ relations with different parts of HQ are related to different knowledge sharing patterns. The literature on HQ disaggregation helps us better understand the nature of subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing patterns.

Conclusions

The study has limitations that indicate future research opportunities. First, the analysis was conducted solely based on the data of Japanese MNCs. Second, the performance implications of reporting to different parts of HQ are beyond the scope of this study. Although identifying the knowledge sharing patterns of subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ was the priority of this study, future research would benefit from investigating the performance implications. Third, since our data were confined to the R&D function regarding corporate HQ, we only observed the R&D dimension of corporate HQ, i.e., corporate R&D HQ. Since the task of corporate HQ is not limited to R&D, future studies can collect data on other aspects of corporate HQ beyond R&D. Fourth, we intentionally asked the respondents to select only one main part of the HQ to which each subsidiary reported to highlight the differences among different reporting relations. Future studies can collect data that reflect the reality of a subsidiary’s simultaneous reporting to different parts of HQ.

That said, this study is an initial attempt to explore the associations between differing parts of the HQ to which subsidiaries report and subsidiaries’ external and internal knowledge sharing (EKS and IKS) patterns. This study contributes to the literature on corporate HQ, global R&D, and MNC innovation in the following ways. First, it demonstrates that the different parts of the HQ to which subsidiaries report make a difference to subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing external and internal to the firm. By comparing corporate R&D HQ with other parts of HQ (i.e., divisional HQ, regional HQ, and top management), the study shows that reporting to different parts of HQ leads subsidiaries to show different knowledge-sharing patterns. Second, the study zooms in on corporate-level HQ by comparing corporate R&D HQ with top management in terms of the way subsidiaries’ reporting relations are related to different patterns of knowledge sharing. These two points contribute to advancing our knowledge about the role of HQ in knowledge flows in MNCs. Despite the growing literature on the role of HQ in MNC’s knowledge management (Ciabuschi et al., 2011b; Ciabuschi et al. 2012; Dellestrand and Kappen 2011; Decreton et al. 2017; Decreton et al. 2019), little is known about the more differentiated role of HQ in knowledge management. We highlight different parts of HQ and show how each is related to different patterns of knowledge sharing by subsidiaries. Third, the study demonstrates how organization design perspectives can better explain the global knowledge sharing of MNCs. The knowledge management literature and organization design literature have further opportunities to share insights. Fourth, this study contributes to the global R&D literature by presenting differences in the knowledge-sharing patterns of R&D subsidiaries reporting to different parts of HQ, which have not been explicitly identified in prior studies.

The study contributes to management practice by implying how organization design matters for subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing patterns. Managers in charge of fostering subsidiaries’ knowledge sharing may attain optimal level of external and internal knowledge sharing by adjusting the subsidiaries’ reporting relations with different parts of HQ.

We adopted an exploratory approach to identify facts and patterns of the associations between overseas R&D subsidiaries’ external and internal knowledge-sharing patterns and the subsidiaries’ reporting relations with different parts of HQ. For this reason, we did not test formal hypotheses by following the spirit of the fact-based approach (Hambrick 2007; Helfat 2007; Menz and Barnbeck 2017). Future studies can pursue this line of research by testing hypotheses. This is our first step in that direction.

Availability of data and materials

Data are not publicly available due to the agreement with RIETI.

Notes

As our study focuses on the R&D function, we only examined the R&D-specific nature of corporate HQ and overseas subsidiaries. For this reason, we positioned corporate R&D HQ as a corporate-level unit. This reflects a unique element of our study.

We classified corporate R&D HQ as a corporate-level unit. Given the exclusive focus of our study on R&D, corporate R&D HQ plays a role as corporate HQ.

Subsidiaries’ reporting relations with corporate R&D HQ, top management, divisional HQ and regional HQ are mutually exclusive since the respondents were asked to specify one primary part of the HQ to which they report.

Although the simultaneous involvement of different parts of HQ is becoming increasingly common (Decreton, et al., 2017; Birkinshaw, et al., 2016), we intentionally asked the respondents to select only one main part of the HQ to which each subsidiary reports. Our intention in doing so was to compare the most salient reporting relations vis-à-vis the others. On the other hand, a downside of this approach was the small number of observations of the reporting relationship, especially the reporting relation with top management.

While allowing the respondents to select multiple levels and parts of HQ would have reflected the reality of the subsidiaries’ multiple reporting relations with HQ and would have allowed a larger number of observations for each reporting relation, this approach would have diluted the differences among differing reporting relations. In contrast, our approach of requesting only one main part of the HQ to which the subsidiaries reported could highlight the relative differences among different parts of the HQ to which the subsidiaries report.

In the original questionnaire, we used the term “business unit” to which overseas R&D subsidiaries reported (see Appendix). Since we meant this as the subsidiary reporting relations with divisional HQ, we used the term “divisional HQ” in this paper.

Although this boundary of science-driven, high-tech industries is rather vague in reality, we consider pharmaceutical/chemical industries to be more science-driven and high-tech than steel, machinery, electronics and electric, automotive, precision machinery, telecommunication and other industries, following prior studies (Song et al., 2011; Asakawa et al., 2018).

Therefore, to capture the relative influence of “R task,” we measured the moderating effect of “R task” on the relative association between the part of HQ and knowledge sharing to obtain a more unbiased assessment. We present the results of the regressions below.

Following a reviewer’s suggestion, we also ran regressions without control variables. The results, which were reported to the editors, confirmed identical patterns of the results presented here.

We also checked interaction terms with “R task” as a moderator, but none of the effects were statistically significant. Since this was beyond the scope of our analysis, we do not report the results in separate tables.

We also checked interaction terms with “R task” as a moderator, but none of the effects were statistically significant. Since this was beyond the scope of our analysis, we do not report the results in separate tables.

Such an orientation can be confirmed by the descriptive statistics shown in Table 5, in which only 28% of the subsidiaries reporting to divisional HQ engaged in an “R task,” which is significantly lower than those reporting to other parts of HQ (χ²= 14.409, p<0.001).

Such a difference between the reporting relation with divisional HQ and that with regional HQ is also consistent with the insights from the organization design literature in which different axes of organizational structures— business dimension vs. geography dimension—have differing patterns regarding the way resources are allocated and managed within the business divisions or geographic areas (Galbraith, 1973; Burton, Obel and Håkonsson, 2006; Westney, 2003). MNCs with geography-based organizational structure are more focused on business in a particular geographic area (Galbraith, 1973).

The literature on regional management classifies different roles of regional HQ and regional management mandates (RMMs); i.e., the former enhances vertical information flows (Schotter et al., 2017; Alfoldi et al., 2012), and the latter enhances “lateral information flows between subsidiaries within a region” (Schotter et al., 2017; Hoenen and Kostova, 2015; Ambos and Schlegelmilch, 2010; Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016; Mahnke, et al., 2012; Amann, Jaussaud and Schaaper, 2014; Asakawa and Lehrer, 2003; Piekkari, Nell and Ghauri, 2010). However, in our data, we only had the “regional HQ” category in our questionnaire, which encompassed the concept of RMMs as well, given the nature of regional HQ responsible for supervising overseas R&D subsidiaries. For this reason, we expected that regional HQ plays the role of knowledge broker among R&D subsidiaries.

Prior studies identified that the HQ plays an administrative, monitoring role as well as an entrepreneurial, value-creating role (Birkinshaw, Braunerhjelm, Holm and Terjesen, 2006; Ciabuschi et al., 2012; Kunisch, 2017; Foss, 1997; Foss, Foss and Nell, 2012). Subsidiaries need to carefully manage an optimal distance from HQ to engage in global innovation activity (Monteiro, Arvidsson, and Birkinshaw, 2008; Ambos, Ambos, Eich and Puck, 2016).

Abbreviations

- HQ:

-

Headquarters

- R&D:

-

Research and development

- MNC:

-

Multinational corporation

- R task:

-

Basic and applied research task

- EKS:

-

External knowledge sharing

- IKS:

-

Internal knowledge sharing

- RMMs:

-

Regional management mandates

References

Alfoldi EA, Clegg LJ, McGaughey SL (2012) Coordination at the edge of the empire: the delegation of headquarters functions through regional management mandates. J Int Manag 18(3):276–292

Allen TJ, Tushman ML, Lee D (1979) Technology transfer as a function of position on research, development, and technical service continuum. Acad Manag J 22:694–708

Almeida P, Phene A (2004) Subsidiaries and knowledge creation: the influence of the MNC and host country on innovation. Strat Manag J 25:847–864

Amann B, Jaussaud J, Schaaper J (2014) Clusters and regional management structures by Western MNCs in Asia: overcoming the distance challenge. Manage Int Rev 54:879–906

Ambos B, Schlegelmilch BB (2010) The new role of regional management. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Ambos T, Ambos B, Eich KJ, Puck J (2016) Imbalance and isolation: how team configurations affect global knowledge sharing. J Int Manag 22(4):316–332

Ambos T, Ambos B, Schlegelmilch B (2006) Learning from foreign subsidiaries: an empirical investigation of headquarters’ benefits from reverse knowledge transfers. Int Bus Rev 15:294–312

Ambos TC, Birkinshaw J (2010) Headquarters’ attention and its effect on subsidiary performance. Manage Int Rev 50(4):449–469

Andersson U, Forsgren M, Holm U (2001) Subsidiary embeddedness and competence development in MNCs: a multilevel analysis. Org Stud 22(6):1013–1034

Andersson U, Forsgren M, Holm U (2002) The strategic impact of external networks: subsidiary performance and competence development in the multinational corporation. Strat Manage J 23(11):979–996

Asakawa K (2001) Organizational tension in international R&D management: the case of Japanese firms. Res Pol 30(5):735–757

Asakawa K, Lehrer M (2003) Managing local knowledge assets globally: the role of regional innovation relays. J World Bus 38:31–42

Asakawa K, Park Y, Song J, Kim S (2018) Internal embeddedness, geographic distance, and global knowledge sourcing by overseas subsidiaries. J Int Bus Stud 49(6):743–752

Baaij MG, Mom TJ, Van den Bosch FA, Volberda HW (2015) Why do multinational corporations relocate core parts of their corporate headquarters abroad? Long Ran Plan 48(1):46–58

Baaij MG, Slangen AH (2013) The role of headquarters–subsidiary geographic distance in strategic decisions by spatially disaggregated headquarters. J Int Bus Stud 44(9):941–952

Bartlett CA, Ghoshal S (1989) Managing across borders: the transnational solution. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

Birkinshaw J, Braunerhjelm P, Holm U, Terjesen S (2006) Why do some multinational corporations relocate their headquarters overseas? Strat Manage J 27(7):681–700

Birkinshaw J, Crilly D, Bouquet C, Lee SY (2016) How do firms manage strategic dualities? A process perspective? Acad Manage Discov 2(1):51–78

Bouquet C, Birkinshaw J (2008) Weight versus voice: how foreign subsidiaries capture the attention of corporate headquarters. Acad Manag J 51(3):577–601

Burton RM, Obel B, Håkonsson DD (2006) Organization design: a step-by-step approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Campbell A, Goold M, Alexander M (1995) Corporate strategy: the quest for parenting advantage. Harvard Bus Rev 73(2):120–132

Cantwell J, Mudambi R (2005) MNE competence-creating subsidiary mandates. Strat Manage J 26:1109–1128

Ciabuschi F, Dellestrand H, Holm U (2012) The role of headquarters in the contemporary MNC. J Int Manag 18:213–223

Ciabuschi F, Dellestrand H, Kappen P (2011a) Exploring the effects of vertical and lateral mechanisms in international knowledge transfer projects. Manage Int Rev 51(2):129–155

Ciabuschi F, Dellestrand H, Martın OM (2011b) Internal embeddedness, headquarters involvement, and innovation importance in multinational enterprises. J Manage Stud 48(7):1612–1639

Ciabuschi F, Forsgren M, Martin M (2011c) Rationality vs. ignorance: the role of MNE headquarters in subsidiaries’ innovation processes. J Int Bus Stud 42(7):958–970

Collis DJ, Young D, Goold M (2007) The size, structure, and performance of corporate headquarters. Strat Manage J 28:383–405

Collis DJ, Young D, Goold M (2012) The size and composition of corporate headquarters in multinational companies: empirical evidence. J Int Manag 18(3):260–275

Decreton B, Dellestrand H, Kappen P, Nell P (2017) Beyond simple configurations: the dual role involvement of divisional and corporate headquarters in subsidiary innovation activities in multibusiness firms. Manag Int Rev 57:855–878

Decreton B, Nell P, Stea D (2019) Headquarters involvement, socialization, and entrepreneurial behaviors in MNC subsidiaries. Long Range Plan 52(4): 101839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.05.005

Dellestrand H, Kappen P (2011) Headquarters allocation of resources to innovation transfer projects within the multinational enterprise. J Int Manag 17(4):263–277

Dellestrand H, Kappen P (2012) The effects of spatial and contextual factors on headquarters resource allocation to MNE subsidiaries. J Int Bus Stud 43(3):219–243

Desai MA (2009) The decentering of the global firm. World Econ 32:1271–1290

Doz Y, Wilson K (2012) Managing global innovation. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

Doz YL, Santos J, Williamson P (2001) From global to metanational: how companies win in the knowledge economy. Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA

Egelhoff WG (1982) Strategy and structure in multinational corporations: an information-processing approach. Admin Sci Quart 27:435–458

Egelhoff WG (1991) Information-processing theory and the multinational enterprise. J Int Bus Stud 22:341–368

Foss K, Foss NJ, Nell PC (2012) MNC organizational form and subsidiary motivation problems: controlling intervention hazards in the network MNC. J Int Manag 18(3):247–259

Foss N (1997) On the rationales of corporate headquarters. Ind Corp Change 6(2):313–338

Frost T (2001) The geographic sources of foreign subsidiaries innovations. Strat Manage J 22(2):101–123

Galbraith JR (1973) Designing complex organizations. Adison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co, Inc., Reading, MA

Galbraith JR (2009) Designing matrix organizations that actually work: how IBM, Procter & Gamble, and others design for success. Jossey-Bass Business and Management, San Francisco, CA

Goold M, Campbell A (2002) Parenting in complex structures. Long Rang Plan 35(3):219–243

Goold M, Campbell A, Alexander M (1998) Corporate strategy and parenting theory. Long Rang Plan 31(2):308–314

Granovetter M (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Amer J Soc 91(3):481–510

Gupta AK, Govindarajan V (1991) Knowledge flows and the structure of control within multinational corporations. Acad Manag Rev 16(4):768–792

Gupta AK, Govindarajan V (2000) Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strat Manage J 21(4):473–496

Haas MR, Hansen M (2007) Different knowledge, different benefits: toward a productivity perspective on knowledge sharing in organizations. Strat Manage J 28(11):1133–1153

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1998) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice-Hall, Jew Jersey

Hambrick DC (2007) The field of management’ devotion to theory: too much of a good thing? Acad Manag J 50(6):1346–1352

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manag Rev 9:193–206

Hansen M, Haas MR (2001) Competing for attention in knowledge markets: electronic document dissemination in a management consulting company. Admin Sci Quart 46:1–28

Helfat CE (2007) Stylized facts, empirical research and theory development in management. Strat Org 5(2):185–192

Hoenen A, Kostova T (2015) Utilizing the broader agency perspective for studying headquarters subsidiary relations in multinational corporations. J Int Bus Stud 46(1):104–113

Howell RD (1987) Covariance structure modeling and measurement issues. J Mark Res 24(2):119–126

Kogut B, Zander U (1992) Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Org Sci 3:383–397

Kogut B, Zander U (1993) Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. J Int Bus Stud 24(4):625–645

Kunisch S (2017) Does headquarters structure follow corporate strategy? An empirical study of antecedents and consequences of changes in the size of corporate headquarters. J Bus Econ Manage 18(3):390–411

Kunisch S, Menz M, Birkinshaw J (2019) Spatially dispersed corporate headquarters: a historical analysis of their prevalence, antecedents, and consequences. Int Bus Rev 28:148–161

Kunisch S, Müller-Stewens G, Campbell A (2014) Why corporate functions stumble. Harvard Bus Rev 92(10):110–117

Lehrer M, Asakawa K (1999) Unbundling European operations: regional management and corporate flexibility in American and Japanese MNCs. J World Bus 34:267–286

Mahnke V, Ambos B, Nell PC, Hobdari B (2012) How do regional headquarters influence corporate decisions in networked MNCs? J Int Manag 18:293–301

Martin JA, Eisenhardt KM (2010) Rewiring: cross-business-unit collaborations in multibusiness organizations. Acad Manag J 53(2):265–301

Menz M, Barnbeck F (2017) Determinants and consequences of corporate development and strategy function size. Strat Org 15(4):481–503

Menz M, Kunisch S, Collis DJ (2015) The corporate headquarters in the contemporary corporation: advancing a multimarket firm perspective. Acad Manage Annals 9(1):633–714

Meyer KE, Mudambi R, Narula R (2011) Multinational enterprises and local contexts: the opportunities and challenges of multiple embeddedness. J Manage Stud 48(2):235–252

Miller CC, Cardinal L, Glick W (1997) Retrospective reports in organizational research: a reexamination of recent evidence. Acad Manag J 40(1):189–204

Monteiro F, Birkinshaw J (2017) The external knowledge sourcing process in multinational corporations. Strat Manage J 38(2):342–362

Monteiro LF, Arvidsson N, Birkinshaw J (2008) Knowledge flows within multinational corporations: explaining subsidiary isolation and its performance implications. Org Sci 19:90–107

Morrison DF (1976) Multivariate statistical methods. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Mudambi R (2011) Commentaries: hierarchy, coordination, and innovation in the multinational enterprise. Glob Strat J 1:317–323

Nell PC, Ambos B (2013) Parenting advantage in the MNC: an embeddedness perspective on the value added by headquarters. Strat Manage J 34(9):1086–1103

Nell PC, Decreton B, Ambos B (2016) How does geographic distance impact the relevance of HQ knowledge? The mediating role of shared context. In: Ambos T, Ambos B, Birkinshaw J (eds) Perspectives on headquarters-subsidiary relationships in the contemporary MNC. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 275–298

Nell PC, Kappen P, Laamanen T (2017) Reconceptualising hierarchies: the disaggregation and dispersion of headquarters in multinational corporations. J Manage Stud 54(8):1121–1143

Oxley J, Rivkin J, Ryall M (2010) The strategy research initiative: recognizing and encouraging high-quality research in strategy. Strat Org 8(4):377–386

Piekkari R, Nell PC, Ghauri PN (2010) Regional management as a system. Manage Int Rev 50(4):513–532

Podsakoff PM, Organ DW (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manage 12:531–544

Poppo L (2003) The visible hands of hierarchy within the M-form: an empirical test of corporate parenting of internal product exchanges. J Manage Stud 40(2):403–430

Saittakari I (2018) The location of headquarters: why, when and where are regional mandates located? Doctoral dissertation 68/2018. Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland

Santor D, Haggerty J, Lévesque J-F, Burge F, Beaulieu M-D, Gass D, Pineault R (2011) An overview of confirmatory factor analysis and item response analysis applied to instruments to evaluate primary healthcare. Healthcare Pol 7(Special Issue):79–92