Abstract

How will digitalization influence the role of corporate headquarters (CHQs) and their relationships with their operating units? We recently asked 67 senior CHQ managers this question. The results suggest that CHQs expect to become more powerful and more involved in their operating units. These conclusions seem to be driven by perceptions that the ongoing digitalization will provide CHQ managers with more timely and better information. In this “Point of View,” we discuss the potential pitfalls of such a narrative. We also offer ideas for how to avoid mistakes and ensure that CHQs increase their value-added in times of digitalization. In particular, we suggest that CHQs place emphasis on social interactions for data to be effectively collected and analyzed, for decision-making power to be adequately allocated, and for CHQ involvement to be informed and necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The role of corporate headquarters (CHQs) is considered one of the key issues in strategy and organization (Menz et al. 2015; Rumelt et al. 1994). As an organizational entity, CHQs perform both administrative and entrepreneurial activities (Chandler 1991; Foss 1997) with the aim of creating value for their corporation beyond their overhead burden. For example, CHQs can provide strategic guidance to their operating units, help identify and realize cross-unit synergies, and limit opportunistic subunit behavior through elaborate monitoring (Ambos et al. 2019; Goold and Campbell 2002; Kostova et al. 2018; Sengul et al. 2012). Research in this area suggests that creating net value for the organization is easier for CHQs when their businesses are related, when information flows efficiently within the organization, when CHQ managers are not suffering from cognitive or social biases such as overconfidence, and when they manage to maintain a fine balance between inter-unit cooperation and competition (e.g., Knott and Turner 2019; Poppo 2003; Tsai 2002).

While the literature has provided a good overall understanding of the role of CHQs in creating value for their organizations (e.g., Foss 1997; Goold and Campbell 1998), scholars have not yet examined in-depth how the ongoing digitalization will influence this issue (Kunisch et al. 2018; Birkinshaw et al. 2018). Our fieldwork with managers across different industries gives us the impression that companies are also puzzled by these developments. For example, digitalization can provide the means for creating online communities across the organization that facilitate knowledge exchange and enable collaborations between dispersed units (Faraj et al. 2011; Tsai 2000). This change could eventually reduce the role of CHQs in intra-organizational coordination. On the contrary, CHQs may gain decision-making power and expand their scope of activities. For example, Galbraith (2014) suggests that big data analytics will push companies to add an additional structural dimension at the top, extending the scope and power of CHQs. Examples in favor of this argument include Procter & Gamble, which created digitally enhanced “Control Towers” on the corporate level to better monitor its supply chain (Galbraith 2014). In sum, there is still much ambiguity concerning what digitalization means for organizational design in general and the role of CHQs in particular.

In this paper, we address the question of how digitalization influences CHQ-subunit relationships. We focus here on the hierarchical (vertical) relationship between CHQs and their operating units (i.e., domestic or foreign subunits) (e.g., Egelhoff 2010), as opposed to corporate functions within CHQs (e.g., Menz et al. 2015). Using insights from our qualitative fieldwork, we developed a questionnaire focusing on the impact of digitalization on intra-organizational issues, particularly on CHQs’ involvement in subunits, the distribution of power between CHQs and subunits, and CHQs’ value-added. In this context, we defined “digitalization” broadly, as we noticed that the term still lacks a universally accepted definition and that practitioners indeed predominantly use and understand the term broadly. To this end, the term digitalization refers here to recent advances in the areas of big data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and automation. In particular, we focus on the new means and tools available in organizations at both CHQs and subunits as a result of digitalization. We collected 67 responses from senior CHQ managers in Austria; 85% of them were members of the executive board or one level below the board. The companies that participated in our survey have an average of 6,000 employees and represent a wide variety of industries, such as consumer goods, automotive, pharmaceuticals, telecom, and banking. After we received insights from those survey responses, we followed up with 15 of our respondents and discussed in detail how they envision the changes that digitalization will bring to CHQs. In this “Point of View,” we report on the results of our study and discuss our view on the most important pitfalls and opportunities of the potential reorganizations resulting from digitalization.

The “stronger CHQ” narrative

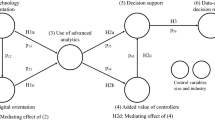

Based on our survey data and interviews with senior CHQ managers, we noticed that an interesting narrative emerged regarding the influence of digitalization on how CHQ-subunit relationships will be organized (see Fig. 1).

First, CHQ managers expect that digitalization will enable them to “have better information and data for decision-making (e.g., through more sophisticated data mining tools)” (94% of the CHQ managers’ answers range between “slightly agree” and “strongly agree”), “have more timely information and data for decision-making (e.g., through real-time dashboards)” (98%), and “better predict relevant factors (e.g., better sales forecasts via predictive analytics)” (91%). There are good reasons to believe that digitalization will provide CHQs with more and better data and information. Indeed, digital tools can automate data collection and analysis about activities occurring in the subunits. For example, we interviewed a large industrial group that installed a new customer-relationship management (CRM) system throughout its entire organization. The interactive dashboards of the software allow CHQ managers to identify key customers, track customer interactions, and monitor sales developments for every subunit—with just a few mouse clicks.

Second, drawing on the assumed higher availability and quality of information in the CHQs, the majority of the CHQ managers in our study anticipate that the CHQs will “take over more activities (i.e., following a more centralized approach)” (70%), “become more powerful compared to their subunits” (73%), and “involve themselves more in subunits’ businesses” (78%). The arguments of CHQ managers for becoming more powerful are based on the idea that they will have the information necessary to efficiently balance adaptation and coordination across their subunits (Chandler Jr 1993; Govindarajan 1986). For instance, CHQ managers could use advanced analytics to evaluate the extent to which particular processes must be adapted to the various subunits. Additionally, with more accurate data and information about their subunits, CHQ managers can become more knowledgeable about when to involve themselves in subunit matters and overrule some of the decisions made in the subunits (Ciabuschi et al. 2011b; Asmussen et al. 2019). In this regard, one CHQ manager from a consumer goods company stated that “thanks to digital tools and systems, there will be more aspects where headquarters have exactly the same insight into facts on the ground as local management, enabling a quicker and more educated dialogue with local operations.” CHQ managers can become more easily aware of activities in the subunits that are diverging from the overall strategy and that may have a detrimental impact on the entire organization. Consequently, CHQ managers might be more involved in redirecting these activities and ensuring consistency across their subunits (Goold and Campbell 1998; Foss 1997). Indeed, CHQ managers of the Dutch engineering service company Royal Imtech would likely have intervened in their fraudulent subunits earlier (potentially avoiding bankruptcy) had they had data and information on the ongoing accounting manipulations (Deutsch and Sterling 2015; Steinglass 2013).

Third, following increased (decision-making) power at the CHQs and higher involvement of CHQ managers in their subunits, CHQ managers assume that they will add greater value to their organization, e.g., through their improved ability to "offer strategic guidance to subunits" (85%), "transfer best practices to subunits" (85%), or "identify and implement synergies between subunits" (85%). The centralization of decision-making and the involvement of CHQs in their subunits can indeed be effective mechanisms to address conflicts between subunits, as well as stimulate inter-unit competition and coopetition (Knott and Turner 2019; Poppo 2003; Tsai 2002). Eventually, CHQ managers anticipate their higher quality involvement in subunits’ activities. For example, knowing about a declining relationship with a particular customer could trigger the involvement of CHQs in ways that solve the issues at hand (Nell and Ambos 2013). Additionally, the involvement of CHQ managers can facilitate knowledge sharing across subunits, potentially decreasing silo thinking and behavior (Ciabuschi et al. 2011a; Goran et al. 2017).

Potential problems

We concur with the expectations of senior CHQ managers about the positive impact of digitalization on CHQs’ role and value creation. However, we also see several challenges in this emerging narrative (without claiming exhaustiveness) and would like to raise a word of caution towards CHQs to critically think not only about the great opportunities of digitalization but also about the risks associated with it and the conditions under which the logic of this positive narrative may not hold (see Fig. 2).

First, one of the assumptions behind this narrative is that digitalization will result in more timely and accurate data and information at CHQs. In our opinion, it is erroneous to think that this will automatically be the case. More data does not necessarily mean better data. As has been shown, executives tend to always ask for more data, often for the sake of gathering new data (Håkonsson and Carroll 2016). There is the risk that some of the extensive data collection efforts under digitalization may not be rigorous enough to generate appropriate data. Moreover, better data does not automatically result in better information (i.e., insights). Reliable data can be processed inaccurately when data analytics tools and algorithms are not appropriately developed or when companies lack the capabilities to adequately interpret the data. MIT Sloan Management Review’s “Annual Data & Analytics Global Executive Study” has shown over the last years that, although companies are experiencing increased access to useful data, most do not have the capabilities to develop insights from this data to guide future strategy (MIT SMR Connection 2019).

Second, another assumption in this narrative is that more timely and accurate data and information in the CHQs should lead to more decision-making power at the CHQs and more involvement of CHQ managers in their subunits. This reasoning is in line with traditional approaches suggesting that decision-making authority should reside where knowledge is located (Chandler 1990). If information is available at the CHQs, decision-making can become more centralized, and CHQ managers can become more involved in their subunits. However, two caveats apply. Subunits may also substantially benefit from digitalization through increased access to high-quality data and information. Hence, relative to their subunits, the CHQs may actually not increase their access to information. Moreover, even if CHQs gain in data and information, they will probably still lack access to the deeply tacit and contextualized knowledge that subunits have about their activities (Grant 1996). We think that these two caveats actually represent opportunities for CHQs to decentralize more activities to and become less involved in their subunits. Then, subunits could make more (accurate) decisions themselves and coordinate among each other, without necessarily consulting with CHQs.

Third, the last part of the narrative implies that more centralized decision-making and greater CHQ involvement in their subunits will add value to their organizations. However, companies that move towards greater centralization run the risk of subunits starting to compete for attention from CHQs, for instance, in trying to influence resource allocation decisions (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). This competition can be particularly problematic if, as a result, subunits limit their lateral interactions with each other (Kogut and Zander 1992; Knott and Turner 2019; Tsai 2002). As research shows, cross-subunit collaborations emanating from, and managed by, the subunits tend to be more effective than corporate-centric collaborations (Martin and Eisenhardt 2010). The reason is that CHQ managers often overestimate their capabilities to organize such collaborations. This failing of CHQs can become even more problematic in the era of digitalization because the use of predictive analytics may unduly increase CHQ managers’ confidence that their decisions are well informed and not questionable. Eventually, this can result in CHQ managers acting as if they know best, neglecting the perspectives of subunit managers (Bouquet et al. 2016). With more centralization, CHQ managers might also make unrealistic requests of their subunits, which will spend additional resources trying to satisfy CHQs (Holm et al. 2017). For instance, short-term performance deviations communicated to CHQs in real time might lead to frequent, unjustified, and ineffective interventions from CHQ managers. This approach can harm motivation and entrepreneurial behaviors in the subunits, thus decreasing the value-adding potential of CHQs (Decreton et al. 2018). Finally, subunit managers might simply mistrust the CHQs’ move towards more centralization and involvement, irrespective of potentially improved information and understanding on the level of the CHQs. This may lead to lower implementation efforts and open resistance of subunit managers to CHQs’ decisions (Foss et al. 2012).

In sum, while most CHQ managers have positive expectations about their role in the era of digitalization, many of the anticipated benefits are based on somewhat simplistic and overly optimistic assumptions. Understanding the potential pitfalls in this way of thinking is a necessary first step in critically evaluating the changes that digitalization brings to intra-organizational issues. Below, we offer ideas for how to address these pitfalls and how to become the value-creating CHQs of the digital future.

Potential remedies

Overall, for CHQs to increase their data-related value-added in times of digitalization, they should not only pay attention to the technical aspects of digitalization but also place an emphasis on the social aspect of organizing their relationships with the subunits. Increased data and computational capabilities are in no way a substitute for good management and social capital in organizations. Excluding subunits and shifting the power to CHQs would be a serious mistake. Smart digitalized management starts with a good understanding of the new changes and possibilities by both CHQs and subunits. This change must be accomplished in close partnership between CHQs and subunits, without overestimating the importance and capabilities of the CHQs and with the profound engagement of the subunit managers. In fact, recent studies (e.g., Håkonsson and Caroll 2016; Sharer 2019) and our interactions with senior executives underscore the continued importance of participative management, empowerment, and justice and trust in digitalized organizations. In the following, we offer three specific sets of recommendations.

First, organizations need to ensure that they have the required digital talent—at all levels of the organization—to obtain more and better data and information thanks to digitalization. Organizations need employees who can collect high-quality data and make appropriate use of it, such as statisticians and data scientists, as well as “light quants” who can bridge the gap between senior decision-makers and data scientists (Davenport 2015). Organizations also need employees who understand when they have sufficient data (Foss and Klein 2014) and who are able to make decisions with an acceptable degree of risk (Håkonsson and Caroll 2016). This trade-off between being highly data-driven and encouraging intuition and speed in decision-making needs to be closely embedded in the organizations’ cultures. Moreover, CHQs must actively integrate subunit managers into the reorganization process that follows digitalization. Engaging subunit managers in these efforts is not only a question of their motivation but also, importantly, the only way to capture their valuable knowledge. Subunit managers possess relevant tacit and contextualized knowledge about which data to collect, how to do so, and how to train algorithms. Subunit managers are also very valuable in interpreting the collected data to increase the quality of the decisions made by subunit and CHQ managers. The involvement of subunit managers will help improve the information systems, the analytical and predictive activities, and the decision-making in the company.

Second, CHQs must seriously consider the question of whether to centralize more activities and become more involved in their subunits as a result of the greater availability of data and information. Digitalization might increase the power of CHQs by equipping them with the necessary information for a broad set of decisions. However, we believe that CHQs could be more effective without implementing more centralized structures and being more involved in their subunits’ activities. In contrast, we view digitalization as a tool that would allow more flexible organizational structures with a better allocation of decision-making power between subunits and CHQs. Indeed, CHQs that possess extensive knowledge about their subunits are in a better position to determine which activities to delegate as well as when and how to intervene in subunit matters (Campbell et al. 2011; Jacobides 2007; Sengul and Gimeno 2013). In some cases, adding value would even mean restraining CHQs from involvement in subunit matters (Asmussen et al. 2019). Eventually, these flexible organizational structures could help empower subunit managers who will still possess unique tacit and contextualized knowledge about their activities.

Third, CHQ managers who decide to centralize more activities and to become more involved in their subunits should put in place mechanisms that ensure higher value-added. For instance, CHQs should be transparent in their decision-making and provide fair and consistent decisions across subunits (Kim and Mauborgne 1993; Nohria and Ghoshal 1994). Moreover, regardless of digitalization, trust and social capital between subunits and CHQs will continue to be critical for knowledge exchange and other collaborative activities. It will be important to maintain socialization mechanisms, such as inter-unit task forces and rotation programs. Indeed, as a result of these exchanges, the involvement of managers from CHQs will be better informed and thus more likely to be needed and desired, as well as perceived as such by managers in the subunits (Decreton et al. 2018; Knott and Turner 2019). In one example of a large bank we worked with, the CHQ accompanied the launch of a corporate-wide digital communication and knowledge exchange platform with a series of international gatherings. The CHQ actively engaged its subunits as well as external startups to discuss new business opportunities and ask for input. This approach resulted in a high degree of offline and online interaction among all participants. The initiative was a great success and led to an increase in the motivation of subunit managers as well as in knowledge-sharing behaviors among them.

Conclusion

In this “Point of View,” we shed initial light on some of the intra-organizational issues that companies will face following digitalization. In particular, we critically discussed an emerging narrative related to the organizational developments that CHQ managers envision. CHQ managers seem to agree that digitalization will increase their power relative to their subunits and the extent to which CHQ managers are involved in their subunits, eventually leading to a higher value-added of CHQs. We raised a word of caution, as we think that it might not always be (or need to be) the case. We primarily emphasized that CHQ managers need to include digital talents and subunit managers in digitalization efforts and go beyond the technical aspect of digitalization. CHQ managers should give importance to processes that increase trust, justice, and social interactions across the organizations so that tacit and contextualized knowledge can be shared. Only in this way will CHQs succeed in increasing their value-added to the organization in the era of digitalization.

Given that this stream of research is still in its infancy, it is currently appropriate to adopt a general approach. However, scholars could provide some nuances to our study. For instance, investigating whether digitalization will distinctively influence single- and multi-business companies could be an interesting avenue for future research. Additionally, we did not find significant differences between industries in the way CHQ managers foresee the influence of digitalization on their activities, and we think that our arguments are applicable to a wide range of industries. Nevertheless, future research could examine which industries are more or less prone to the issues we mentioned. Furthermore, we excluded companies that were born-digital (e.g., Facebook, Google) or had dispersed CHQs, but it would be interesting to know how digitalization influences CHQs-subunit relations in these companies, especially given recent advances in research on differences between integrated and dispersed CHQs (Kunisch et al. 2019; Nell et al. 2017).

Moreover, we focused our study on CHQ managers, and although their perspectives are highly relevant to the issues at hand, they might be biased with regard to the importance of the CHQs (Kunisch et al. 2014; Young et al. 2000). Our follow-up interviews gave us confidence that we capture an emerging narrative of more powerful CHQs that is indeed linked to digitalization. Additionally, we do not claim that the narrative will enfold in all organizations (i.e., our message is not that digitalization will necessarily make CHQs more powerful). Rather, we point out to problems that could occur for organizations that do implement the changes mentioned as a result of digitalization, and we suggest potential remedies to these problems. Still, we encourage scholars to consider a wider range of actors (e.g., subunit managers, subcontractors) to develop a more comprehensive view of digitalization and CHQ-subunit relationships.

Furthermore, some authors have debated whether organizations will look radically different in the future (e.g., the discussions around boss-less organizations) (Foss and Dobrajska 2015; Lee and Edmondson 2017; Puranam and Håkonsson 2015). While our interactions with CHQ managers did not reveal any “radical” changes in the way their relations with their subunits will be organized as a result of digitalization, we encourage future debates on the extent of changes that digitalization will bring to these organizational design issues. Also, investigating the influence of particular digital means and tools (e.g., CRM systems versus digital communication platforms) represents an important avenue for future research as they might have varying effects on CHQ-subunit relationships (Bloom et al. 2014).

Finally, we would like to expand on our paper with some higher-level opportunities of digitalization. We argued that digitalization should not necessarily change the balance of power within organizations. In fact, it could provide a more reliable platform for analysis and decision-making, which is shared by CHQs and their subunits. This change, in turn, could reduce the agency problems and animosity that have been commonplace in many CHQ-subunit relationships (Ambos et al. 2019; Hoenen and Kostova 2015; Kostova et al. 2018). Hence, we consider digitalization a tool that will make room for better collaborations and improved decision-making in organizations. We envision digital CHQ-subunit relationships in which actors decide together what type of information is useful for both sides, which sources of data are the best, what the optimal level of data is, and how to best interpret it. More generally, we hope for optimized and balanced CHQ-subunit relationships that utilize digital capital to improve management.

References

Ambos B, Kunisch S, Leicht-Deobald U, Steinberg AS (2019) Unravelling agency relations inside the MNC: the roles of socialization, goal conflicts and second principals in headquarters-subsidiary relationships. J World Bus 54(2):67–81

Asmussen CG, Foss NJ, Nell PC (2019) The role of procedural justice for global strategy and subsidiary initiatives. Glob Strateg J. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1341

Birkinshaw J, Collis DJ, Foss N, Hoskisson RE, Kunisch S, Menz M (2018) Call for papers for a special issue: corporate strategy and the theory of the firm in the digital age. J Manag Stud Available via http://www.socadms.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Corporate-Strategy-and-the-Theory-of-the-Firm-in-the-Digital-Age.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr 2019

Bloom N, Garicano L, Sadun R, Van Reenen J (2014) The distinct effects of information technology and communication technology on firm organization. Manag Sci 60(12):2859–2885

Bouquet C, Birkinshaw J (2008) Weight versus voice: how foreign subsidiaries gain attention from corporate headquarters. Acad Manag J 51(3):577–601

Bouquet C, Birkinshaw J, Barsoux JL (2016) Fighting the “headquarters knows best syndrome”. MIT Sloan Manage Rev 57(2):59–66

Campbell A, Kunisch S, Müller-Stewens G (2011) To centralize or not to centralize? McKinsey Quarterly (3):97–102

Chandler AD (1990) Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the industrial enterprise, vol 120. MIT Press, Cambridge

Chandler AD (1991) The functions of the HQ unit in the multibusiness firm. Strateg Manage J 12(S2):31–50

Chandler AD Jr (1993) The visible hand. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Ciabuschi F, Dellestrand H, Martín OM (2011a) Internal embeddedness, headquarters involvement, and innovation importance in multinational enterprises. J Manage Stud 48(7):1612–1639

Ciabuschi F, Forsgren M, Martín OM (2011b) Rationality vs ignorance: the role of MNE headquarters in subsidiaries’ innovation processes. J Int Bus Stud 42(7):958–970

Davenport T (2015) In praise of “light quants” and “analytical translators”. In: Deloitte insights. Deloitte. Available via https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/deloitte-analytics/articles/in-praise-of-light-quants-and-analytical-translators.html. Accessed 15 Mar 2019

Decreton B, Nell PC, Stea D (2018) Headquarters involvement, socialization, and entrepreneurial behaviors in MNC subsidiaries. Long Range Plan. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.05.005

Deutsch A, Sterling T (2015) Dutch engineer Imtech bankrupt, parts sold to investors. Reuters. Available via https://www.reuters.com/article/royal-imtech-bankruptcy/update-1-dutch-engineer-imtech-bankrupt-parts-sold-to-investors-idUSL5N10O47O20150813. Accessed 15 Mar 2019

Egelhoff WG (2010) How the parent headquarters adds value to an MNC. Manage Int Rev 50(4):413–431

Faraj S, Jarvenpaa SL, Majchrzak A (2011) Knowledge collaboration in online communities. Organ Sci 22(5):1224–1239

Foss K, Foss NJ, Nell PC (2012) MNC organizational form and subsidiary motivation problems: controlling intervention hazards in the network MNC. J Int Manag 18(3):247–259

Foss NJ (1997) On the rationales of corporate headquarters. Ind Corp Change 6(2):313–338

Foss NJ, Dobrajska M (2015) Valve’s way: vayward, visionary, or voguish? J Organ Des 4(2):12–15

Foss NJ, Klein PG (2014) Why managers still matter. MIT Sloan Manage Rev 56(1):73–80

Galbraith JR (2014) Organizational design challenges resulting from big data. J Organ Des 3(1):2–13

Goold M, Campbell A (1998) Desperately seeking synergy. Harvard Bus Rev 76(5):130–143

Goold M, Campbell A (2002) Parenting in complex structures. Long Range Plan 35(3):219–243

Goran J, LaBerge L, Srinivasan R (2017) Culture for a digital age. McKinsey Quarterly (10):1–10

Govindarajan V (1986) Decentralization, strategy, and effectiveness of strategic business units in multibusiness organizations. Acad Manag Rev 11(4):844–856

Grant RM (1996) Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg Manage J 17(S2):109–122

Håkonsson T, Carroll T (2016) Is there a dark side of Big Data–point, counterpoint. J Organ Des 5(1):1–5

Hoenen AK, Kostova T (2015) Utilizing the broader agency perspective for studying headquarters–subsidiary relations in multinational companies. J Int Bus Stud 46(1):104–113

Holm AE, Decreton B, Nell PC, Klopf P (2017) The dynamic response process to conflicting institutional demands in MNC subsidiaries: an inductive study in the sub-Saharan African E-commerce sector. Glob Strateg J 7(1):104–124

Jacobides MG (2007) The inherent limits of organizational structure and the unfulfilled role of hierarchy: lessons from a near-war. Organ Sci 18(3):455–477

Kim WC, Mauborgne RA (1993) Procedural justice, attitudes, and subsidiary top management compliance with multinationals’ corporate strategic decisions. Acad Manag J 36(3):502–526

Knott AM, Turner SF (2019) An innovation theory of headquarters value in multibusiness firms. Organ Sci. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2018.1231

Kogut B, Zander U (1992) Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organ Sci 3(3):383–397

Kostova T, Nell PC, Hoenen AK (2018) Understanding agency problems in headquarters-subsidiary relationships in multinational corporations: a contextualized model. J Manage 44(7):2611–2637

Kunisch S, Menz M, Birkinshaw J (2019) Spatially dispersed corporate headquarters: a historical analysis of their prevalence, antecedents, and consequences. Int Bus Rev 28(1):148–161

Kunisch S, Menz M, Collis DJ (2018) Call for papers: corporate headquarters in the 21st century. Journal of Organization Design. Available via http://www.orgdesigncomm.com/resources/Documents/CfP_CorporateHQ.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr 2019

Kunisch S, Müller-Stewens G, Campbell A (2014) Why corporate functions stumble. Harvard Bus Rev 92(12):110–117

Lee MY, Edmondson AC (2017) Self-managing organizations: exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Res Organ Behav 37:35–58

Martin JA, Eisenhardt KM (2010) Rewiring: cross-business-unit collaborations in multibusiness organizations. Acad Manag J 53(2):265–301

Menz M, Kunisch S, Collis DJ (2015) The corporate headquarters in the contemporary corporation: advancing a multimarket firm perspective. Acad Manag Ann 9(1):633–714

MIT SMR Connection (2019) Data, analytics, & AI: how trust delivers value. Available via https://sloanreview.mit.edu/offers-sas-data-analytics-report-2019/?utm_medium=adv&utm_source=facebook&utm_campaign=CSdarpt19. Accessed 15 Mar 2019

Nell PC, Ambos B (2013) Parenting advantage in the MNC: an embeddedness perspective on the value added by headquarters. Strateg Manage J 34(9):1086–1103

Nell PC, Kappen P, Laamanen T (2017) Reconceptualising hierarchies: the disaggregation and dispersion of headquarters in multinational corporations. J Manage Stud 54(8):1121–1143

Nohria N, Ghoshal S (1994) Differentiated fit and shared values: alternatives for managing headquarters-subsidiary relations. Strateg Manage J 15(6):491–502

Poppo L (2003) The visible hands of hierarchy within the M-form: an empirical test of corporate parenting of internal product exchanges. J Manage Stud 40(2):403–430

Puranam P, Håkonsson DD (2015) Valve’s way. J Organ Des 4(2):2–4

Rumelt RP, Schendel DE, Teece DJ (1994) Fundamental issues in strategy: a research agenda. Harvard Business School Press, Brighton

Sengul M, Gimeno J (2013) Constrained delegation: limiting subsidiaries’ decision rights and resources in firms that compete across multiple industries. Admin Sci Quart 58(3):420–471

Sengul M, Gimeno J, Dial J (2012) Strategic delegation: a review, theoretical integration, and research agenda. J Manage 38(1):375–414

Sharer K (2019) Headquarters as hardware and software. J Organ Des 8(4):1–3

Steinglass M (2013) Former Imtech managers face possible criminal complaint for fraud. Financial Times. Available via https://www.ft.com/content/c09ac9d6-d80b-11e2-b4a4-00144feab7de. Accessed 15 Mar 2019

Tsai W (2000) Social capital, strategic relatedness and the formation of intraorganizational linkages. Strateg Manage J 21(9):925–939

Tsai W (2002) Social structure of “coopetition” within a multiunit organization: coordination, competition, and intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organ Sci 13(2):179–190

Young D, Goold M, Blanc G, Buehner R, Collis DJ, Eppink J, Tadao K, Seminario GJ (2000) Corporate headquarters: an international analysis of their roles and staffing. Pearson Education, London

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge fruitful conversations with and thoughtful comments of Patricia Klopf and Tatiana Kostova on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding for this paper.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PN and JS developed the survey design and collected data. JS analyzed the data. All authors worked on the paper’s structure and key points. BD and JS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitt, J., Decreton, B. & Nell, P.C. How corporate headquarters add value in the digital age. J Org Design 8, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41469-019-0049-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41469-019-0049-6