Abstract

Global health reciprocal innovation emphasizes the movement of technologies or interventions between high- and low-income countries to address a shared public health problem, in contrast to unidirectional models of “development aid” or “reverse innovation”. Evidence-based interventions are frequently adapted from the setting in which they were developed and applied in a new setting, presenting an opportunity for learning and partnership across high- and low-income contexts. However, few clear procedures exist to guide researchers and implementers on how to incorporate equitable and learning-oriented approaches into intervention adaptation across settings. We integrated theories from pedagogy, implementation science, and public health with examples from experience adapting behavioral health interventions across diverse settings to develop a procedure for a bidirectional, equitable process of intervention adaptation across high- and low-income contexts. The Mutual capacity building model for adaptation (MCB-MA) is made up of seven steps: 1) Exploring: A dialogue about the scope of the proposed adaptation and situational appraisal in the new setting; 2) Developing a shared vision: Agreeing on common goals for the adaptation; 3) Formalizing: Developing agreements around resource and data sharing; 4) Sharing complementary expertise: Group originating the intervention supporting the adapting group to learn about the intervention and develop adaptations, while gleaning new strategies for intervention implementation from the adapting group; 5) Reciprocal training: Originating and adapting groups collaborate to train the individuals who will be implementing the adapted intervention; 6) Mutual feedback: Originating and adapting groups share data and feedback on the outcomes of the adapted intervention and lessons learned; and 7) Consideration of next steps: Discuss future collaborations. This evidence-informed procedure may provide researchers with specific actions to approach the often ambiguous and challenging task of equitable partnership building. These steps can be used alongside existing intervention adaptation models, which guide the adaptation of the intervention itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The movement of ideas or technology from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to high-income countries (HICs) has been called “reverse innovation” [1]. This concept, however, echoes the extractive and hegemonic relationship that has traditionally characterized the relationship between HICs and LMICs [2]. “Development aid” is similarly unidirectional, with knowledge and resources flowing from HICs to LMICs, often without respect for the strengths of LMIC communities [3]. In contrast, “reciprocal innovation” [4, 5] is the idea that people from different settings have similar challenges and can share ideas and resources across settings [6]. While there is a growing literature on the theoretical importance of reciprocal innovation [2], there have been few examples of its operationalization [5, 7,8,9,10] or structured procedures to guide practice.

As the field of global health endeavors to be more equitable and anti-colonialist [11,12,13], we need strategies that foster collaboration and acknowledge that many health challenges are truly global [14]. We cannot ignore vast resource differences between HICs and LMICs, which have led to inequity in access to healthcare services, but also must acknowledge the inequity in healthcare within HICs. These resource differences and inequities are rooted in historical injustice (e.g., slavery, colonialism, exploitation for natural resources). Resource redistribution must be coupled with a push for LMIC leadership and relationships between HICs and LMIC collaborators characterized by mutual respect. HIC researchers who look for LMIC partners for guidance on addressing problems they face “at home” may approach work in LMICs with greater humility [13]. Yet as implementing evidence-based interventions from LMICs in HICs increases, there is a need to be “guardrails” to ensure that the LMIC originators are included, compensated, and acknowledged.

We propose a procedure for a mutual capacity building approach when adapting interventions from a low-income context to a high-income context or vice-versa. Cultural adaptation is a first step in the implementation and scale-up of evidence-based interventions, as they must be tailored to the needs and resources of the new setting prior to widespread implementation. Adaptation may be particularly important in behavioral health, as how mental health conditions present and are best addressed may be specific to a context and culture [15,16,17]. The procedure we propose could be used by researchers, implementers, program developers, or practitioners [18]. Although partnership building cannot be entirely driven by a set of steps to follow, providing steps for building such partnerships could prompt conversations, provide concrete activities that funders could support, and lend clarity to approaching the amorphous challenge of mutual capacity building.

Intervention adaptation: a space for LMIC and HIC collaboration

Evidence-based health interventions, particularly behavioral interventions, are frequently adapted from the setting in which they were initially developed, often translated, and tested for use in a new setting or population [19]. Adaptation facilitates scale-up of an evidence-based practice, while being responsive to the needs and cultural practice of new communities or populations [15, 20]. In many cases, interventions initially developed in HICs are adapted for LMICs and for delivery by non-specialist or lay providers [5, 16, 21]. For instance, Life-Steps, a brief problem-solving and motivational interviewing based approach to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV, was initially developed in the United States [22], but has now been adapted for use in Zimbabwe [23] and South Africa [24]. Increasingly, however, interventions from LMICs are also being adapted for HICs. For instance, the Friendship Bench [25], a lay health worker-delivered intervention for depression care in Zimbabwe based on problem solving therapy, was adapted for implementation in New York City [26]. Intervention adaptation has traditionally been focused on a single setting, rather than rooted in mutual learning: people in Setting B adapt an intervention from Setting A to fit their context and culture, but people from Setting A may not take lessons from Setting B’s adaptation to their setting.

There are many existing models to guide intervention adaptation, such as the widely used Assessment, Decision, Adaptation, Production, Topical experts, Integration, Training, and Testing (ADAPT-ITT), developed for HIV interventions [20], mental health Cultural Adaptation and Contextualization for Implementation (mhCACI) developed for psychological and other mental health interventions [18], and PRISSMA which centers culturally-informed adaptation [27]. These and other models typically provide a set of steps or principles that researchers and practitioners can use to tailor an intervention to a new setting or population [27, 28]. What has been lacking, however, is a clear procedure for how to ensure collaboration during adaptation processes that span historical and current power imbalances.

Development of a procedure for mutual capacity building for intervention adaptation

Our goal was to develop an evidence-informed procedure for mutual capacity building during intervention adaptation. We drew from both relevant theoretical foundations and our team’s experiences working across HIC and LMIC settings, including several pilot studies. To develop the Mutual Capacity Building Model for Adaptation (MCB-MA), we first analyzed a series of in-depth case studies describing behavioral health interventions that had been collaboratively adapted and implemented in both HICs and LMICs. Through the case studies, we highlighted strategies these projects used to facilitate collaborative work (full case studies and strategies described elsewhere: [29]). We also piloted a mutual capacity building process for sharing study results and merging data across an LMIC and HIC that were implementing a similar peer-delivered behavioral activation intervention [10]. Our team then discussed examples of where collaboration had broken down or perpetuated inequities, which highlighted key gaps that needed to be filled through a more structured mutual capacity building process. To address those gaps, our international team proposed a series of steps, then refined them through smaller group discussions, grounded in theory and lived experience of trying to address the challenges in equitable partnerships. In Supplementary Table 1, we highlight several relevant theories that guided us, including Freirean participatory dialogue, community-based participatory research, theory of change, and several models from implementation science [30,31,32]. In Table 1, we briefly describe illustrative examples and counterexamples that informed our work, drawn from our experiences conducting studies and implementing behavioral health interventions in the United States, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Mozambique, Brazil, and Australia, among other countries. While the results of these and other projects conducted between HICs and LMICs have been published [33,34,35,36,37,38], these publications often lack granularity on how the partnership was formed and maintained, or the results are published separately without attention to lessons learned between sites.

Mutual capacity building model for adaptation (MCB-MA)

Here, we consider an intervention to be a specific treatment protocol or treatment package (e.g., number of sessions, delivery modality, interventionist, content), rather than a broader therapeutic modality (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy). We consider adaptation to be a process of modifying an intervention for a new setting following an existing adaptation framework, such as ADAPT-ITT [20] or mhCACI [18]. We assume that all adaptation frameworks involve some formative work to develop an understanding of the new context, development of an adapted intervention protocol, and pilot testing or initial implementation of the adapted intervention in the new setting.

MCB-MA is predicated on the idea that a group that either developed the intervention or is well-established in using it (“originating group”) and the group that is adapting the intervention for their setting (“adapting group”) collaborate in a bidirectional partnership. The originating group brings expertise on the intervention and the adapting group expertise on the context and culture where it will be implemented [17, 39]. Either the LMIC or HIC group can be the originating group. Importantly, engagement in MCB-MA is premised on the recognition of a common challenge. The magnitude of the problem may differ between settings; although lack of access to specialist and other mental health services may be a challenge in many US and Australian cities, for instance, there remains far less access in LMICs like Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and South Africa [40].

Implementing this procedure in its entirety or in the prescribed sequence of steps may not be feasible or useful in every situation. We propose this as a starting point for conversations about mutual learning and a procedure from which groups could engage with select steps.

MCB-MA steps

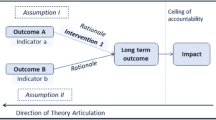

MCB-MA has three broad phases, which are summarized in Table 2; the overall model is displayed in Fig. 1.

Phase 1: partnership building

The goal of this phase is to agree to collaborate to adapt an intervention and develop the formal and informal structures to govern sharing of knowledge, power, and other resources during adaption.

Step 1: Exploring a potential partnership and the new setting

This step provides a space for open discussion about whether both groups want to engage in shared work around a common problem and time for appraisal of the new context. In initial conversations, the groups can develop shared understanding of the mutual challenge or challenges that they hope to address with the intervention; share information about their context, strengths, and needs [27]; and discuss interest in taking a mutual capacity building approach. Either group can initiate the conversation about engaging in the process of forming a partnership to adapt an intervention for one or both settings. Ideally, this conversation would occur before a project is funded so that both groups have a say in formative project development and budgeting [41]. This foundational work, however, may require funding, particularly to support LMIC partners.

Additionally, while each partner may understand their own health system and the context of the challenge they are trying to address, they can share this context with the other potential partner and conduct a situational appraisal to fill any knowledge gaps, laying the foundation for contextually appropriate future work. This appraisal may be particularly important if the adapting group is working within their own country but in an region or health system where they do not live or work, such as a rural area. All members of the adapting team, including both frontline staff and team leaders, should be familiar with existing services, local needs, cultural norms, and policies and regulations affecting the place where they will be adapting the intervention. A shared contextual understanding is important to establish up front, as it may affect what intervention the teams choose to adapt and how they go through the adaptation and implementation process.

Step 2: Developing a shared vision

This step allows both groups to make their adaptation plans more concrete, mixing discussion of logistics with broader conversations about distribution of power and resources.

The groups may already come to the process with an intervention in mind but should explicitly agree on the intervention to be adapted. Based on the contexts, resources available, situational appraisal, and intervention itself, the groups can select an intervention adaptation framework [42] and discuss the adaptation process:

-

1)

Values: Do the groups agree on goals for intervention adaptation and principles that will govern the process [30, 43]?

-

2)

Language: In what language will the intervention be delivered in the adapting setting, and what are translation needs? If the groups have different native languages, in what language will meetings take place? Can some team activities take place primarily in the non-dominant language?

-

3)

What are “core” elements of the intervention that must be preserved and cannot be adapted across settings [44]? What are “deep structure” adaptations that may be necessary to fit within the cultural values and health or social system in the new setting [17, 45]?

-

4)

Timeline: Over what time period does the adapting group propose to adapt, pilot, and implement the intervention [32]?

-

5)

Planning for feedback: What data does the adapting group plan to collect during the adaptation and pilot process? Can those data be shared with the originating group [19, 46]?

-

6)

Strengths and areas for growth: The groups can share the areas where they feel they have human or resources, knowledge, or skills and areas where they lack these. The groups can work to identify opportunities for mutual support and learning.

-

7)

Power, privilege, and resources: The groups may have imbalances in resources, formal training, or levels of historical advantage. This can be discussed in initial conversations so that the groups can share how they will create ways of working to mitigate these. Very concretely, the groups may discuss how project resources will be directed to not further entrench advantage (e.g., pay parity between sites; ensuring that indirect costs are held by the lower resource site to contribute to institutional development) [31].

-

8)

Building team unity: Discuss how to come together and build unity as a project team. This could involve structured team-building discussions and exercises or more informal social events or gatherings. The relationships within the team are foundational for the success of the adaptation process and may necessitate conscious effort to develop team culture [27].

Step 3: Formalizing

Often, projects require grants, contracts, data sharing agreements, or memoranda of understanding. This will look different for every project and set of institutions. This step ensures that those formal processes are not addressed until there have been some more fundamental conversations about partnership.

The group can discuss what they need to formalize the partnership and promote clear expectations, roles, and understanding across groups. This could include rights to use or adapt the intervention materials, data sharing agreements, ethical approvals, publication agreements, exchange of existing monetary resources between the two groups (for instance, the adapting group purchasing rights to the intervention materials or the HIC group supporting adaptation in an LMIC given deep resource inequalities and greater access to funding for HICs), or individual or joint funding applications to support the project. Pragmatically, the groups might consider applying for one of the growing number of funding opportunities for planning or partnership building [47] and structuring subcontracts to allow for flexible reallocation of funds between sites given the iterative nature of the MCB-MA process.

Phase 2: partnership sustaining

The goal of this phase is to adapt the intervention in a way that includes both groups in complementary roles.

Step 4. Sharing complementary expertise

Throughout the process of adaptation, the two groups can identify complementary areas of expertise, whether that is the intervention (originating group is expert), the setting (adapting group is expert), or specific methodologies or techniques (either).

In most adaptation frameworks, the adapting group does the formative work in their setting. The adapting group will also need to familiarize themselves with the intervention itself. The originating group can act as consultants, providing input on intervention components and core elements as the adapting group develops the adapted protocol. This may help ensure fidelity to mechanisms of action and other core elements of the original evidence-based intervention [48]. The originating group may also share lessons learned from their efforts to implement the intervention, helping the adapting group consider implementation from the outset [44]. This is also, however, a time during which the originating group can learn from the adapting group’s process and changes to the intervention, providing ways that they could improve on the intervention or its implementation in their setting.

Building on their discussion of strengths and areas for growth, the groups could identify ways to support each other in their adaptation of the intervention. For instance, they may identify complementary strengths and weaknesses in the methodologies used to adapt the intervention, such as qualitative interviewing, design of pilot trials, community engagement, writing, implementation science, or community engagement [27]. This could create opportunities for “just in time” teaching as the intervention is being adapted and piloted.

Step 5. Reciprocal training

This step ensures that the originating group is involved in training the interventionists in the new setting in the adapted intervention. Currently, this has often happened when the intervention is being adapted from an HIC to LMIC (HIC partners do the training) but less common when an intervention is adapted from an LMIC to HIC (LMIC partners may not be invited to HIC to provide training). This step is a reminder that bidirectional training should occur in both circumstances.

Given the experience that the originating group has in delivering the intervention, they may be able to train the adapting group in the intervention, whether training only the research team or directly training the new interventionists. It is likely not sufficient to have only the originating group train the interventionists, as they will have limited experience in the language, population, and setting. Being involved in training would give the originating group an opportunity to witness the implementation of the intervention in a new setting, possibly informing their own implementation strategies. Direct involvement of the originating group in interventionist training may not be feasible or desired in all contexts but can be considered as a possible opportunity for joint learning. Involvement of people with lived experience of the target health conditions is vital both as trainers and recipients of training [49, 50].

Step 6: Mutual feedback

This step provides a space for the groups to share implementation or effectiveness outcomes of the adaptation process and reflect on lessons learned for both sites.

While bidirectional feedback will ideally be happening throughout the process, there should be particular focus on mutual feedback and evaluation of the process after initial implementation and effectiveness results are available. The adapting group could share the data they collected during the adaptation process and initial implementation and solicit feedback from the originating group on how to improving the intervention or its implementation [19, 46]. The originating group could then reflect on lessons that they are taking away for their own setting from the adaptation and implementation of the intervention in the new setting. The groups can also use these meetings as an opportunity to discuss how adaptations might affect clinical or implementation outcomes, share ideas about future evaluation [51], and reflect on or formally evaluate the MCB-MA process itself.

Phase 3: partnership longevity

The goal of this phase is to make time to discuss next steps for any future joint work.

Step 7: Consideration of next steps: exploring continuity between the adaptation partners

At the close of the intervention adaptation, partners can discuss what comes next, including subsequent research or implementation steps. This is also an opportunity to share results of any formal or informal evaluation of the MCB-MA process that the teams did. This discussion can also include whether they would like to continue collaborating and, if so, in what form. This could take a similar format to “Exploring” and could start another cycle of MCB-MA components. It is also an opportunity for either group to discontinue the partnership and renegotiate the terms of collaboration.

Future directions and opportunities for changing how we work

We have outlined a procedure for incorporating mutual capacity building into intervention adaptation: MCB-MA. Our goal was to provide researchers and practitioners with a set of steps that they can use to guide bidirectional adaptation processes. We hope this may help increase the frequency and equity of reciprocal innovation in global mental health. Bidirectional learning will take place within intrinsically unequal and flawed systems and hope that the mutual capacity building process can help to shift, mitigate, or question some of the systems and power hierarchies prevalent in global health research.

Mutual capacity building is, in many ways, a way of working and attitude toward learning and partnership that is challenging to capture in a set of steps. However, having a specific set of steps can make this concept more actionable, provide guidance for groups that want to work together or funders that aim to support bidirectional projects. While this work draws on our experience in mutual capacity building, the process has not been tested in its entirety and will require additional testing and refinement. Our goal in proposing MCB-MA was to contribute to an ongoing conversation, rather than provide the final word.

MCB-MA should be further evaluated in future work and compared with less structured processes for collaborative intervention adaptation. There has been little prior empirical or theoretical work on how to evaluate or define success in mutual capacity building. Most distally, mutual capacity building could improve clinical outcomes by facilitating shared knowledge and iterative improvement of the intervention and its implementation. These clinical outcome changes, however, may be difficult to evaluate, as they may be small effects and result over a longer time. Mutual capacity building is primarily a process change that aims to increase equity and inclusion in the way that research is conducted, which may be best evaluated by examining team outcomes (e.g., longevity of collaboration, parity in funding or promotions, or perception of psychological safety within the team). Finally, the implementation of the MCB-MA model itself could be evaluated by assessing the feasibility of each step, relative cost of this more involved process, whether team members like the process (acceptability) or feel it meets their needs (appropriateness) [52], and the reach of MCB-MA (for instance, has use extended beyond a small number of well-resourced academic centers?) [53]. Selecting outcomes to evaluate, however, is complicated by the multiple, potentially competing, goals of multi-site partnership. Each group of collaborators who undertake this process will come from a different socioeconomic and cultural context and face a different set of health system needs and resources. Groups may weigh differently how much they prioritize, for instance, equity within the team, receiving ongoing funding to facilitate partnership longevity, or public health impact from the intervention on which the team works. While these priorities could be mutually reinforcing, they are often in tension.

There are numerous barriers that prevent bidirectional, mutually beneficial research partnerships from forming and being sustained. These limit the feasibility of implementing MCB-MA but also underscore the importance of having a model such as this. First, often unintentional, yet nevertheless supremacist attitudes of white, wealthy, HIC-based leaders have long discounted LMIC knowledge, practices, and ways of approaching problems [54]. These attitudes may limit the openness of HIC practitioners and researchers to learn from collaborators in other settings [11, 54]. Biases, however, can work bidirectionally, with LMIC-based leaders perceiving HIC collaborators as condescending, overly removed, or only a source of funding. Second, many funding structures are set up to support either projects based in HICs, often in the country where the funder is based (“community health”) or international projects in LMICs (“global health”) [14], not projects that cut across settings. Funders may also not be willing to invest in the process of building a partnership, without promise of tangible deliverables. Lack of funding for robust partnership building processes may make the activities in Phase 1 of MCB-MA very challenging. However, having a model like MCB-MA may help structure and provide a theoretical basis for how teams approach seeking such funding. Third, building deep and respectful partnerships is challenging and a time-intensive investment, particularly across a vast distance, numerous time zones, and different cultures. Partners are often balancing time-constrained schedules, competing priorities, and lack funding to support initial conversations [11]. MCB-MA cannot address all of these challenges, but it does provide researchers and implementers with some pragmatic guidance that can structure their initial efforts to overcome these barriers.

MCB-MA is a model for centering equity and collaboration within research processes—a scope that has inherent limitations. It challenges ways of working within a single project but does not directly challenge the broader hierarchies and inequities in research or development fields or broader social and political systems in which we work. In his seminal writings, Brazilian scholar and activist Paolo Freire (Supplementary Table 1) places his deconstruction of the power relations between student and teacher necessarily within a broader vision of social change. Breaking down the micro-hierarchies within existing systems is not meaningful without concurrently working to deconstruct the broader structural violence that led to these systems and hierarchies [55, 56]. This procedure does not necessitate advocacy or other work that challenges structural inequities between countries, regions, or cities or the inequities created by existing research funding structures and academic hierarchies. It also does not directly address social forces including sexism, racism, or ableism. This is both a limitation of this procedure and an opportunity to embed it within existing efforts for structural activism and social change.

Our approach has several limitations. First, we drew from several different cases of mutual capacity building to illustrate the steps of MCB-MA. None of these cases, however, used the full MCB-MA model. Rather, our experiences in mutual capacity building allowed us to test components of this process and identify activities that facilitated shared learning, which we incorporated into the full model. Evaluation of implementation outcomes, particularly the feasibility and acceptability of the MCB-MA model within diverse research and practitioner teams, is essential. Second, we drew primarily on experiences working between HICs and LMICs and from experience working within behavioral health to inform the development of MCB-MA. This procedure, however, could also be used between two settings within an HIC or LMIC or between an upper-middle income country and a low-income country. It could also be used in fields outside of behavioral health [57]. Third, MCB-MA is potentially more resource-intensive than approaches to intervention adaptation that have less intentional focus on partnership building and mutual feedback. There may be a trade-off between putting resources toward this foundational partnership building and toward scaling an intervention. This trade-off is important to acknowledge and may make all or some parts of MCB-MA less useful in some situations, including humanitarian contexts [58], where rapid adaptation may be imperative. However, even in these cases, we hope the values shared in MCB-MA can provide a useful framework for approaching mutual capacity building.

Conclusions

MCB-MA is among the first models to define a process for mutual capacity building. The steps outlined contribute to the ongoing discourse around how to engage in shared learning across populations and sites. This procedure requires further implementation, evaluation, and iterative improvement based on lessons learned from its use in different sites. Use of this procedure should go together with greater efforts to develop cultural humility or critical consciousness training, particularly for HIC collaborators. Changing the ways in which we work is an essential part to making the field of global health more equitable. Facilitating opportunities for more equitable collaboration and LMIC leadership is a change that could have far reaching clinical and policy impacts.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Change history

07 July 2024

The article title has been updated.

Abbreviations

- ADAPT-ITT:

-

Assessment, Decision, Adaptation, Production, Topical experts, Integration, Training, and Testing

- HICs:

-

High-income countries

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MCB-MA:

-

Mutual Capacity Building Model for Adaptation

- mhCACI:

-

Mental health Cultural Adaptation and Contextualization for Implementation

References

Bhattacharyya O, Wu D, Mossman K, Hayden L, Gill P, Cheng YL, et al. Criteria to assess potential reverse innovations: opportunities for shared learning between high- and low-income countries. Glob Health. 2017;13(1):4.

Jack HE, Myers B, Regenauer KS, Magidson JF. Mutual capacity building to reduce the behavioral health treatment gap globally. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2020;47(4):497–500.

Gautier L, Sieleunou I, Kalolo A. Deconstructing the notion of “global health research partnerships” across Northern and African contexts. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(Suppl 1):49.

Sors TG, O’Brien RC, Scanlon ML, Bermel LY, Chikowe I, Gardner A, et al. Reciprocal innovation: a new approach to equitable and mutually beneficial global health partnerships. Glob Public Health. 2022;18(1);1–13.

Turan JM, Vinikoor MJ, Su AY, Rangel-Gomez M, Sweetland A, Verhey R, et al. Global health reciprocal innovation to address mental health and well-being: strategies used and lessons learnt. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl 7):e013572.

Binagwaho A, Nutt CT, Mutabazi V, Karema C, Nsanzimana S, Gasana M, et al. Shared learning in an interconnected world: innovations to advance global health equity. Glob Health. 2013;9:37.

Giusto A, Jack HE, Magidson JF, Ayuku D, Johnson S, Lovero K, Hankerson SH, Sweetland AC, Myers B, Fortunato Dos Santos P, Puffer ES, Wainberg ML. Global Is Local: Leveraging Global Mental-Health Methods to Promote Equity and Address Disparities in the United States. Clin Psychol Sci. 2024;12(2):270-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026221125715.

Vinikoor MJ, Sharma A, Murray LK, Figge CJ, Bosomprah S, Chitambi C, et al. Alcohol-focused and transdiagnostic treatments for unhealthy alcohol use among adults with HIV in Zambia: a 3-arm randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2023;127:107116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2023.107116.

Gagnon KW, Levy S, Figge C, Wolford Clevenger C, Murray L, Kane JC, et al. Telemedicine for unhealthy alcohol use in adults living with HIV in Alabama using common elements treatment approach: a hybrid clinical efficacy-implementation trial protocol. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;33:101123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101123.

Jack HE, Anvari MS, Abidogun TM, Ochieng YA, Ciya N, Ndamase S, et al. Applying a mutual capacity building model to inform peer provider programs in South Africa and the United States: a combined qualitative analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;120:104144.

Chibanda D, Jack HE, Langhaug L, Alem A, Abas M, Mangezi W, et al. Towards racial equity in global mental health research. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(7):553–5.

Weine S, Kohrt BA, Collins PY, Cooper J, Lewis-Fernandez R, Okpaku S, et al. Justice for George Floyd and a reckoning for global mental health. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2020;7:e22.

Buyum AM, Kenney C, Koris A, Mkumba L, Raveendran Y. Decolonising global health: if not now, when? BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(8):e003394.

Fischer SE, Patil P, Zielinski C, Baxter L, Bonilla-Escobar FJ, Hussain S, et al. Is it about the ‘where’ or the ‘how’? Comment on defining global health as public health somewhere else. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5):e002567.

Cabassa LJ, Baumann AA. A two-way street: bridging implementation science and cultural adaptations of mental health treatments. Implement Sci. 2013;8:90.

Le PD, Eschliman EL, Grivel MM, Tang J, Cho YG, Yang X, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of evidence-based task-sharing mental health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review using implementation science frameworks. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):4.

Bonilla-Escobar FJ, Osorio-Cuellar GV, Pacichana-Quinayaz SG, Sanchez-Renteria G, Fandino-Losada A, Gutierrez MI. Do not forget culture when implementing mental health interventions for violence survivors. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22(9):3053–9.

Sangraula M, Kohrt BA, Ghimire R, Shrestha P, Luitel NP, Van’t Hof E, et al. Development of the mental health cultural adaptation and contextualization for implementation (mhCACI) procedure: a systematic framework to prepare evidence-based psychological interventions for scaling. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2021;8:e6.

Heim E, Mewes R, Abi Ramia J, Glaesmer H, Hall B, Harper Shehadeh M, et al. Reporting cultural adaptation in psychological trials - the RECAPT criteria. Clin Psychol Eur. 2021;3(Spec Issue):e6351.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2008(47 Suppl 1):S40–6.

Vellakkal S, Patel V. Designing psychological treatments for scalability: the PREMIUM approach. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134189.

Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-steps: applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cogn Behav Pract. 1999;6(4):332–41.

Bere T, Nyamayaro P, Magidson JF, Chibanda D, Chingono A, Munjoma R, et al. Cultural adaptation of a cognitive-behavioural intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe: Nzira Itsva. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(10):1265–76.

Magidson JF, Joska JA, Belus JM, Andersen LS, Regenauer KS, Rose AL, et al. Project Khanya: results from a pilot randomized type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of a peer-delivered behavioural intervention for ART adherence and substance use in HIV care in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 2):e25720.

Chibanda D, Weiss HA, Verhey R, Simms V, Munjoma R, Rusakaniko S, et al. Effect of a primary care-based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2618–26.

Rosenberg T. Depressed? Here’s a bench. Talk to me. New York; New York Times: 2019. Sect. Opinion.

Wainberg ML, McKinnon K, Mattos PE, Pinto D, Mann CG, de Oliveira CS, et al. A model for adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions to a new culture: HIV prevention for psychiatric patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):872–83.

Wainberg ML, Alfredo Gonzalez M, McKinnon K, Elkington KS, Pinto D, Gruber Mann C, et al. Targeted ethnography as a critical step to inform cultural adaptations of HIV prevention interventions for adults with severe mental illness. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2007;65(2):296–308.

Giusto A, Jack HE, Magidson JF, Ayuku D, Johnson S, Lovero K, et al. Global is local: leveraging global mental-health methods to promote equity and address disparities in the United States. Clin Psychol Sci. 2024;12(2):270–89.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202.

Wallerstein N, Giatti LL, Bógus CM, Akerman M, Jacobi PR, De Toledo RF, et al. Shared participatory research principles and methodologies: perspectives from the USA and Brazil—45 years after Paulo Freire’s “pedagogy of the oppressed.” Societies. 2017;7(2):6.

Breuer E, Lee L, De Silva M, Lund C. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:63.

Magidson JF, Kleinman MB, Bradley V, Anvari MS, Abidogun TM, Belcher AM, et al. Peer recovery specialist-delivered, behavioral activation intervention to improve retention in methadone treatment: results from an open-label, type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation pilot trial. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;108:103813.

Magidson JF, Joska JA, Myers B, Belus JM, Regenauer KS, Andersen LS, et al. Project Khanya: a randomized, hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of a peer-delivered behavioral intervention for ART adherence and substance use in Cape Town, South Africa. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(33).

Michelson D, Malik K, Parikh R, Weiss HA, Doyle AM, Bhat B, et al. Effectiveness of a brief lay counsellor-delivered, problem-solving intervention for adolescent mental health problems in urban, low-income schools in India: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(8):571–82.

Kane JC, Sharma A, Murray LK, Chander G, Kanguya T, Skavenski S, et al. Efficacy of the Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA) for unhealthy alcohol use among adults with HIV in Zambia: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(2):523–36.

Wainberg ML, Mann CG, Norcini-Pala A, McKinnon K, Pinto D, Pinho V, et al. Challenges and opportunities in the science of research to practice: lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial of a sexual risk-reduction intervention for psychiatric patients in a public mental health system. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(4):349–59.

Wainberg ML, Gouveia ML, Stockton MA, Feliciano P, Suleman A, Mootz JJ, et al. Technology and implementation science to forge the future of evidence-based psychotherapies: the PRIDE scale-up study. Evid Based Ment Health. 2021;24(1):19–24.

Bass JK, Bolton PA, Murray LK. Do not forget culture when studying mental health. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370(9591):918–9.

Sorsdahl K, Petersen I, Myers B, Zingela Z, Lund C, van der Westhuizen C. A reflection of the current status of the mental healthcare system in South Africa. SSM-Ment Health. 2023;4:100247.

Oetzel JG, Boursaw B, Magarati M, Dickson E, Sanchez-Youngman S, Morales L, et al. Exploring theoretical mechanisms of community-engaged research: a multilevel cross-sectional national study of structural and relational practices in community-academic partnerships. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):59.

Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, Boing E, Udelson H, Wood R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):125.

Weiss CH. Nothing as practical as good theory: exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In: New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: concepts, methods, and contexts. Vol. 1. 1995. p. 65–92.

Card JJ, Solomon J, Cunningham SD. How to adapt effective programs for use in new contexts. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(1):25–35.

Willis HA, Gonzalez JC, Call CC, Quezada D, Scholars For Elevating E, Diversity S, et al. Culturally responsive telepsychology & mHealth interventions for racial-ethnic minoritized youth: research gaps and future directions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022;51(6):1053–69.

Chambers DA, Norton WE. The adaptome: advancing the science of intervention adaptation. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4 Suppl 2):S124–31.

Planning grant for Fogarty HIV research training program for low- and middle-income country institutions (D71 clinical trial not allowed). National Institutes of Health; 2022. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-22-152.html.

Solomon J, Card JJ, Malow RM. Adapting efficacious interventions: advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(2):162–94.

Gurung D, Kohrt B, Rai S. The PhotoVoice method for collaborating with people with lived experience of mental health conditions to strengthen mental health services. Camb Prisms Glob Ment Health. 2023;10:e80.

Sartor C. Mental health and lived experience: the value of lived experience expertise in global mental health. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2023;10:e38.

Kirk MA, Moore JE, WiltseyStirman S, Birken SA. Towards a comprehensive model for understanding adaptations’ impact: the model for adaptation design and impact (MADI). Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):56.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

Abimbola S, Pai M. Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet (London, England). 2020;396(10263):1627–8.

McKenna B. Paulo Freire’s blunt challenge to anthropology: create a pedagogy of the oppressed for your times. Crit Anthropol. 2013;33(4):447–75.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin Classics; 2017.

Segev T, Harvey AP, Ajmani A, Johnson C, Longfellow W, Vandiver KM, et al. A case study in participatory science with mutual capacity building between university and tribal researchers to investigate drinking water quality in rural Maine. Environ Res. 2021;192:110460.

Perera C, Salamanca-Sanabria A, Caballero-Bernal J, Feldman L, Hansen M, Bird M, et al. No implementation without cultural adaptation: a process for culturally adapting low-intensity psychological interventions in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2020;14:46.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, specifically National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA057443, PI: Magidson; R33DA057747, PI: Magidson; R01DA056102, PI: Magidson; R61AT010799, PI: Magidson; R21DA053212, PI: Magdison), the National Institutes of Health HEAL Initiative (R61AT010799; PI: Magidson), National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH129420, PI: Jack; R34MH122268, PI: Myers, Magidson; R34MH122268, PI: Magidson; T32MH096724, PI: Wainberg; U19MH113203, PI: Wainberg, Oquendo), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA025947, PI: Wainberg), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1H79FG000751-01, PI: Wainberg), National Instute of Mental Health/Fogarty (D43TW011302, PI: Sohn, Wainberg; D43TW009675, PI: Wainberg, Oquendo, Moormahomed). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJ, JM, and AG conceptualized the study. RM, TB, RV, MW, BM, GW, RD, JM, and AG contributed examples and helped define the model. HJ and AR wrote the first draft and led revisions of the manuscript. All authors provided edits on and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This manuscript does not report data from human participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jack, H.E., Giusto, A., Rose, A.L. et al. Mutual capacity building model for adaptation (MCB-MA): a seven-step procedure for bidirectional learning and support during intervention adaptation. glob health res policy 9, 25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-024-00369-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-024-00369-8