Abstract

Background

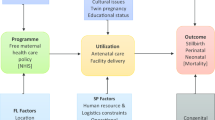

Payment methods are known to influence maternal care delivery in health systems. Ghana suspended a piloted capitation provider payment system after nearly five years of implementation. This study aimed to examine the effects of Ghana’s capitation policy on maternal health care provision as part of lesson learning and bridging this critical literature gap.

Methods

We used secondary data in the District Health Information Management System-2 and an interrupted time series design to assess changes in level and trend in the provision of ANC4+ (visits of pregnant women making at least the fourth antenatal care attendance per month), HB36 (number of hemoglobin tests conducted for pregnant women who are at the 36th week of gestation) and vaginal delivery in capitated facilities-CHPS (Community-based Health Planning and Services) facilities and hospitals.

Results

The results show that the capitation policy withdrawal was associated with a statistically significant trend increase in the provision of ANC4+ in hospitals (coefficient 70.99 p < 0. 001) but no effect in CHPS facilities. Also, the policy withdrawal resulted in contrasting effects in hospitals and CHPS in the trend of provision of Hb36; a statistically significant decline was observed in CHPS (coefficient − 7.01, p < 0.05) while that of hospitals showed a statistically significant trend increase (coefficient 32.87, p < 0.001). Finally, the policy withdrawal did not affect trends of vaginal delivery rates in both CHPS and hospitals.

Conclusions

The capitation policy in Ghana appeared to have had a differential effect on the provision of maternal services in both CHPS and hospitals; repressing maternal care provision in hospitals and promoting adherence to anemia testing at term for pregnant women in CHPS facilities. Policy makers and stakeholders should consider the possible detrimental effects on maternal care provision and quality in the design and implementation of per capita primary care systems as they can potentially impact the achievement of SDG 3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global concerns for the need to improve maternal and neonatal health have led to many interventions to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality by 2030 [1]. Health systems have developed different payment systems to balance incentives for service provision with the need for cost control [2]. However, many of these payment system reforms have mixed results on service provision [2, 3] and maternal health services in particular [4, 5].

In many Sub-Saharan African countries, health insurance schemes have played a key role in facilitating access and use of maternal health services and promoting a significant reduction of the high maternal morbidity and mortality in the sub-region [6, 7]. Health insurance schemes have also positively impacted increased services utilisation by pregnant women in Senegal and Mali [7], skilled birth delivery in Rwanda [8], and utilisation of postnatal care in Mauritania [9]. In Ghana, several studies suggest that more women receive ANC4+ visits per pregnancy and are likely to have a skilled provider delivery if covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) [10,11,12,13,14,15]. What remains unclear is whether payment systems such as the capitation payment mechanisms used by health insurance schemes influence the provision of maternal care.

Capitation payment is a fixed amount of money paid to a provider for an individual’s healthcare needs over a specified period [16]. Blended capitation, where capitation is combined with another payment system for provider payment, have been used in several countries [17]. The impact of these capitation based payments on the quality and quantity of maternal health services have been mixed. Whereas some studies report an improvement [18,19,20], others suggest a worsening of the quality of prenatal care [21, 22]. In high income countries, capitation payment is common in primary care settings [23].

Capitation as a payment mechanism is uncommon in African health systems. Currently, many African countries are using capitation in combination with other payment methods [24, 25]. Kenya is a case in point where capitation was combined with Fee for Service for provider payment [24]. In Ghana, a capitation pilot was introduced for primary care in 2012 and discontinued in 2017 [26, 27]. In that pilot, the NHIS clients chose their preferred primary provider (PPP) to obtain needed outpatient health services with an option of a change of provider after 6 months [26]. Emergency care was to be paid for under the Ghana Diagnosis Related Groups (G-DRGs), while specialised services (referral) were to be paid for under the DRG. To qualify for reimbursement non-emergency referrals must emanate from a client's PPP [28]. Clients had to pay for the cost of self referred specialised services. Non emergency primary care services obtained from a facility other than a client's PPP had to be paid for out of pocket [28]. The healthcare facilities considered for choice as PPP spanned from CHPS, health centres, polyclinics and hospitals [10, 26, 29]. Maternal health services, including routine antenatal care consultations, laboratory tests (venereal disease research laboratory tests, urine dipstick tests, hemoglobin checks), delivery and postnatal care were initially fully part of the basket of services covered in capitation. Later skilled delivery was dropped from the basket in response to concerns of stakeholders in 2014 [28, 30]. After the suspension of the policy in 2017, primary care reverted to being paid for under the G-DRGs and the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) no longer required clients to have a PPP [31]. The monthly payments to facilities by the NHIS were also discontinued [31]. Some studies show that capitation in Ghana achieved cost containment, created competition and encouraged the efficient use of resources [32] and reduced outpatient utilisation [33]. However, knowledge and perception of the policy were poor [26]. In the specific case of maternal health services, as posited by Comfort et al. [34], payment mechanisms in any insurance scheme can potentially affect their provision in health facilities. One of the reasons for capitation in Ghana was to provide financial resources for primary outpatient service provision, especially those in the capitation basket [28]. The NHIS reimbursements were typically in arrears for up to 6 months; hence, capitation payments served as a critical resource for service providers and service provision since these were predictable and always paid on time [32]. Therefore, the subsequent withdrawal of the capitation policy could potentially affect service provision in general and critical maternal health services in particular. The uncentatinty about the likely effect of the piloted and its discontinuation on provision of maternal care represents a critical knowledge gap necessary for policy makers.

To fill this gap, we evaluated the effect of the withdrawal the capitation poliy on the provision of maternal care in CHPS and hospital level facilities. In this study we aimed to analyse the levels and trends of provision of ANC4+, HB36 and facility delivery in CHPS and public hospital level facilities during and after the suspension of the capitation policy in the Ashanti Region of Ghana.

Methods

Study design

We used the single group interrupted time series design to estimate the effects of the withdrawal of the capitation policy by examining the change in level and slope of three maternal health service provision while controlling for secular trends[35]. This design is appropriate where no comparison group is available. The effects of the policy withdrawal are then deduced from the level and trend changes after the intervention [35].

Study setting

The study was conducted in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, where capitation was introduced in January 2012 and discontinued in August 2017. The Ashanti region was selected for piloting the capitation to control costs arising from high expenditure on claims [33]. Even though the capitation covered all facilities, including CHPS, we focused on maternal care provison in the 720 CHPS facilities and the 25 primary district hospitals in Ashanti region. The focus on maternal health stems from the increased trend in inequality in the use of maternal health services in recent time in health facilities and the potential that these are affected by the capitation policy. We also focused on these two facility types (CHPS and hospitals) because they typically close the interaction between the start and end of primary maternal care provision. Additionally, CHPS form one of Ghana’s pathway to achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) through primary health care (PHC) [36]. In Ghana’s referral system, the polyclinic and health centres are supposed to receive referrals from CHPS facilities and in turn refer to the district hospital for all medical conditions they cannot treat [37]. However, in practice, CHPS and polyclinics often refer directly to the hospital in their catchment area [38].

Data sources

Data were obtained from the DHIMS 2 which is an electronic database introduced to help healthcare managers improve upon the collation and analysis of routine service data [39]. The DHIMS 2 keeps database for services provided across all facilities. We extracted maternal health service provision data for all CHPS and public hospitals from the database. This database is managed by the Centre for Health Information Management (CHIM) of the Ghana Health Service. Every month, health facilities supply routine healthcare data for entry into this database [39].

Data access and extraction

Data were extracted in Excel by a trained District health information officer between October 1, 2020 and November 31, 2020 using a data extraction sheet. The data were transferred from Excel to Stata 15.0 for management and analysis.

Sample size

The sample comprised all the 720 CHPS and 25 primary district hospitals with data sets available in the DHIMS 2. The indicators of interest were aggregated on monthly basis across the 31 consecutive months preceding the withdrawal of capitation (from January 2015 to July 2017) and for 29 consecutive months after the withdrawal of the capitation, from August 2017 to December 2019.

Participants/study population

The study participants constituted pregnant women who had recorded more than four antenatal visits and attended a health facility in a given month. It also included women who had their hemoglobin levels checked at their 36th week and mothers who delivered in a given month in CHPS facilities and hospitals.

Study variables

The study included three maternal care indicators; ANC4+, HB36 and delivery. ANC4+ represents the number of women who received at least their fourth scheduled ANC visit in a particular month. HB36 represents the number of laboratory tests done for women in their 36th week of pregnancy in a given month. Delivery represents the number of births delivered at a facility in a given month. These indicators were chosen because, they are indices of provision of quality maternal care in any pregnancy. While ANC4+ measures the likelihood of receiving effective maternal health interventions [40], HB36 measures the health facility’s readiness in the assessment and preparation to identify and manage anemia in the peripartum period. Despite being dropped from the capitation basket, (vaginal) delivery rates in health facilities are surrogate measures of skilled birth uptake and also the acceptability of maternal care services by pregnant women.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics such as the mean, minimum, maximum and the standard deviation of maternal health service provision indicators during capitation and after its discontinuation, were calculated. The segmented regression model was employed to analyse the levels and trends of service provision during and after the discontinuation of capitation. The regression is presented in Eq. (1):

where Yt is the maternal care indicator of interest, \(\beta 0\) represents the intercept or pre-withdrawal level of care before the withdrawal of capitation, \(\beta 1\) is the trend in the provision of care until the withdrawal of capitation, \(\beta 2\) represents the change in the level care provision in theperiod immediately following the withdrawal of capitation (compared to the counterfactual), and \(\beta 3\) represents the difference between pre-and post-capitation withdrawal trends in the provision of care.

Significant P values in \(\beta 2\) show an immediate effect of the withdrawal of capitation and in \(\beta 3\) show effects of capitation withdrawal until Dec 2019. Autocorrelation was corrected and the corresponding Dubin-Watson (DW) statistic was reported. DW values close to 2 indicate no serious autocorrelation. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The average number of monthly ANC4+ visits in CHPS level facilities increased from 253 (min: 165, max: 383, SD: 50) during capitation to 389 (min:304, max: 544 SD: 54.01) after the discontinuation of the capitation policy. However, in the hospital level, average monthly ANC4+ visits decreased from 2553 (min:1721, max:4579, SD:778) during the capitation period to 1953 (min:1462, max 2569, SD:273) post capitation withdrawal. The results are shown in Table 1.

When considering HB36 for CHPS level facilities, Table 1 shows that the average number of HB36 checks performed per month decreased from 249 (min: 63, max:577, SD: 131) during the capitation period to 192 (min:112, max 416; SD 52) after discontinuation. In hospital level, average monthly checks dropped from 1684 (min 1232, max 2443, SD 272) to 1494 (min:1162; max:2037, SD: 180) after discontinuation of capitation.

By contrast, the average number of deliveries increased from 184 (min 119; max: 278 SD: 46) during capitation to 314 (min: 227; max: 416; SD 52) for the period after the discontinuation of capitation in CHPS facilities, while in hospitals the average deliveries decreased from 2103 (min:1736, max:2484, SD:218) to 2085 (min:1745, max:2495, SD:196).

Regression results

Table 2 shows that the capitation policy's discontinuation did not significantly affect the pre-existing level of care provision for all three indicators (ANC4+ visits, HB36 tests or deliveries) in CHPS or hospitals.

However, there were some effects on the trend of provision of care for these indicators. Specifically, we observed a statistically non significant increasing trend for ANC4+ visits in CHPS, which continued after the withdrawal of the policy. For hospitals, a declining trend during capitation (− 63.61), changed into a significantly positive trend after capitation (70.99) as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

The results further show that in CHPS, an increasing trend in HB36 tests during the capitation policy was reversed after the discontinuation of the policy (− 7.01). By contrast, in hospitals, a declining trend in the number of HB36 during capitation, changed into an increasing trend after the end of capitation (32.78).

Concerning deliveries, the discontinuation of capitation had no significant effect on the trend in CHPS or hospitals.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of the withdrawal of capitation on maternal healthcare indicators (ANC4+, HB36 and vaginal delivery) in CHPS and hospitals. The key finding was that the withdrawal of the capitation policy was followed by an increase in the trend of provision of ANC4+ and HB36 in hospitals while hindering the trend of HB36 at CHPS facilities. Other findings were that there was no effect of the withdrawal of capitation on the trend of vaginal delivery rates in CHPS or hospitals.

Several reasons could account for the key finding of increased trends of ANC4+ and HB36 in hospitals compared to CHPS after the withdrawal (meaning hospitals were more incentivised to provide quality antenatal care after the capitation withdrawal).

Foremost, the finding confirm, hospitals preferred the G-DRG over capitation as a payment method for their services as reported by an earlier study in the four Regions where capitation was later extended to [29]. However, while Andoh-Adjei et al. [29] investigated preference of payment methods by healthcare providers through a perception study, the current study gives additional detail on service provision which focuses on a providers’ preferred payment method. The results however conflict Andoh-Adjei et al.’s finding that that in the case of Ashanti Region, providers preferred capitation to DRG for primary maternal care service delivery.

Also, it is possible that the increase in the trend of both ANC4+ and HB36 in hospitals after the policy withdrawal indicates that capitation failed to meet the quality of maternal care expectation by pregnant women. We argue so because ANC4+, an index of the likelihood of receiving effective antenatal contact for the improvement of the quality of maternal care and one of the tracer indicators for SDG 3.8.1[40] declined during the capitation pilot, only recovering after the discontinuation. ANC4+ measures the minimum required contact between pregnant women and health care providers for safe antenatal care. Similarly, the increased number of HB36 tests confirms the increased trend of compliance with the WHO checklist of tests required for quality care in pregnancy in Ghana at the 36th week [41]. This is in spite of the fact that prior trends in provision might have been mitigated by the blend of capitation with other payment methods for hospitals during the capitation policy implementation [42, 43]. While our the study agrees with findings by Hennig-Schmidt et al.[44], it conflicts with that of Ponce et al., and van-Dijk et al. [45, 46], that capitation is associated with an improvement in adherence to quality standards. The results of these earlier studies [44,45,46] may differ from our results because of the specific capitation packages, provider profiles and disease conditions used to evaluate service quality. Additionally these were not conducted on maternal health services.

Furthermore, the statistically significant increase in the trends of ANC4+ and HB36, after the policy withdrawal, could mean that capitation induced poorer provider–client relationships in hospitals, congruent with findings in Thailand [47], Canada [48] and the USA [49]. However, this argument is contradicts the expectation that capitation would increase provider–client trust [50].This is because for the specific case of maternal health services, in the Ghanaian context, pregnant women prefer providers they can trust [51] and will patronise their services more. This probably explains the trends of maternal service provision observed after the policy withdrawal.

Additionally, the significantly lower HB36 trends in CHPS after the withdrawal of capitation could imply that CHPS level facilities had a critical support for their laboratories from the stable advance payments in capitation. This observation is similar to findings by Mills et al. [47]. However, these results are contrary to expectations after findings by Andoh-Adjei et al. [29], that there were no significant association between the CHPS level of care and provider preference of G-DRG under capitation, probably due to the low number of CHPS level providers in their study. Once the per capita payments were no longer being made after the policy withdrawal, in CHPS, pregnant women were now referred to obtain these tests at hospitals. This is perhaps reflects in the the increased provision of HB36 tests observed in hospitals. On the other hand, it could be confounded by moral hazard or supplier induced demand [52] found by earlier studies as attributes of increased laboratory service for insured clients in hospitals.

Moreover, the capitation policy promised the reinforcement of the gatekeeper system with more stringent referral requirements [28]. After its withdrawal, increased trends of ANC4+ and HB36 in hospitals may indirectly indicate its effectiveness at gatekeeping during the policy, driving healthcare provision to lower-level facilities (CHPS and health centres). Although CHPS, were not the only lower level facility, the HB36 trends in CHPS (increased) and hospitals (decreased) prior to the withdrawal of capitation may lend support to this assertion.

Finally, the increased trends in ANC4+ and HB36 in hospitals post capitation suspension, may reflect changes in general service readiness (GSR) of hospitals. GSR indexes the readiness of a health facility to provide care [53]. It may have been the case that the increased GSR in hospitals after the introduction of the NHIS [53], declined contrary to policy expectations during capitation [30]. Increased HB36 trend in hospitals after the policy withdrawal suggests capitation may have been associated with lower GSR during its implementation even though the NHIS is historically noted to have increased GSR after its introduction [53]. This finding also suggests that DRG primary care payments in hospitals may be associated with increased service readiness rather than capitation.This confirms concerns expressed by stakeholders that the introduction of capitation would probably affect healthcare providers negatively [27].

Our study has some limitations. Though it relied on readily available secondary DHIMS 2 data, such data is commonly subject to input errors, extraction errors and data discrepancies. The extraction errors were attenuated by making a second health information officer extract the maternal care data for comparison. We relied on data validation routinely done by facility heads for all data monthly to apply to our results. To strengthen future research results, primary collation of facility data will increase the internal validity of studies of a similar type, although studies [39] have confirmed the completeness and accuracy of the DHIMS 2 data, especially, with respect to maternal care indicators. Ideally, we should obtain all data points before the introduction of capitation, during the capitation and after the removal of the policy to allow for a more robust inferential analysis. However, the 60 months considered is far above the minimum of 9 data points before and after a policy change for interrupted time series analysis [54]. Our study was not insulated from the effects of other system-level confounders; this could have been minimised by introducing a control group and multiple interruptions in the time series analysis and a difference in difference analysis. However, at the time of this study, it was not possible to have access to the national database since doing so required many bureaucratic procedures and processes that could not be overcome within the limited time available for conducting this research. Future studies using the national dataset, allowing for the inclusion of control regions, will shed more light on the increasing potential of the capitation payment system for maternal care provision. The study relied on aggregated data which calls for cautious interpretation. The study did not look at the individual pregnant women socio demographic characteristics in its design. Though a qualitative focused group discussion with participants will address this, it will create another problem of recall bias.

Conclusions

The capitation policy repressed trends of provision of quality care in hospitals and improved the compliance of CHPS with the WHO recommended laboratory care in pregnancy The discontinuation of the policy probably impacted negatively on the gatekeeper system with regards to the provision of quality maternal care in hospitals. These findings imply that policy makers, particularly, the NHIA, may have to redesign and redefine the basket of services for a future capitation based payments for primary maternal care. This will help Ghana achieve the SDG targets of reduced maternal deaths (SDG 3.1), neonatal care (SDG 3.2) and improved PHC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the study are not publicly available due to the institutional policy of the CHIM of the Ghana Health Service but are available from thecorresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANC4+:

-

Number of facility antenatal care attendance of atleast 4 in the index pregnancy

- CHPS:

-

Community based health planning and services

- CHIM:

-

Centre for health information management

- DHIMS:

-

District Health Information Management System

- DW:

-

Dubin Watson

- GSR:

-

General Service Readiness

- HB36:

-

Number of hemoglobin tests at 36th week of gestation

- NHIA:

-

National Health Insurance Scheme

- NHIS:

-

National Health Insurance Scheme

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Cooperatiion And Development

- PHC:

-

Primary Health Care

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

WHO. Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage 2019 global monitoring report executive summary. 2019;151.

Kutzin J, Ministry of Health, MOH, World Health Organization, Tawiah EO, Myint CY, et al. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:602–11.

Berenson RA, Shartzer A, Murray RC. Strengthening primary care delivery through payment reform. 2020.

Wright J. The link between provider payment and quality of maternal health services. 2017.

Kuunibe N, Lohmann J, Hillebrecht M, Nguyen HT, Tougri G, De Allegri M. What happens when performance-based financing meets free healthcare? Evidence from an interrupted time-series analysis. 2020;1–12.

Ansu-Mensah M, Mohammed T, Udoh RH, Bawontuo V, Kuupiel D. Mapping evidence of free maternal healthcare financing and quality of care in sub-saharan africa: a systematic scoping review protocol. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:4–9.

Smith KV, Sulzbach S. Community-based health insurance and access to maternal health services: evidence from three West African countries. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:2460–73.

Soeters R, Peerenboom PB, Mushagalusa P, Kimanuka C. Performance-based financing experiment improved health care in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0019.

Renaudin P, Prual A, Vangeenderhuysen C, Ould Abdelkader M, Ould Mohamed Vall M, Ould El Joud D. Ensuring financial access to emergency obstetric care: three years of experience with Obstetric Risk Insurance in Nouakchott, Mauritania. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;99:183–90.

Abduali IA, Adams A-M, Abdulai M-E. Seeking healthcare under the National Health Insurance Scheme’s capitation payment method in Wa Municipality, Ghana: subscribers’ perspectives. Technol Innov Dev. 2018;11:45–54.

Agbanyo R. Ghana’s national health insurance, free maternal healthcare and facility-based delivery services. Afr Dev Rev. 2020;32:27–41.

Awoonor-Williams JK, Tindana P, Dalinjong PA, Nartey H, Akazili J. Does the operations of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS ) in Ghana align with the goals of Primary Health Care? Perspectives of key stakeholders in northern Ghana. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16:1–11.

Bonfrer I, Breebaart L, Van De Poel E. The effects of Ghana’s national health insurance scheme on maternal and infant health care utilization. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–13.

Bosomprah S, Ragno PL, Gros C, Banskota H. Health insurance and maternal, newborn services utilisation and under-five mortality. Arch Public Health. 2015;73:1–7.

Twum P, Qi J, Aurelie KK, Xu L. Effectiveness of a free maternal healthcare programme under the National Health Insurance Scheme on skilled care: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in two districts in Ghana. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022614.

WHO. The world health report. Health systems financing. 2010.

Organisation for economic cooperation and developmentration development and C. Better ways to pay for health care. OECD; 2016.

Kaestner R, Dubay L, Kenney G. Managed care and infant health: an evaluation of Medicaid in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1815–33.

Howell EM, Dubay L, Kenney G, Sommers AS. The impact of medicaid managed care on pregnant women in Ohio: a cohort analysis. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:825–46.

Griffin JF, Hogan JW, Buechner JS, Leddy TM. The effect of a Medicaid managed care program on the adequacy of prenatal care utilization in Rhode Island. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:497–501.

Yan J. The impact of medicaid managed care on obstetrical care and birth outcomes: a case study. J Womens Health. 2020;29:167–76.

Ray WA, Gigante J, Mitchel EF, Hickson GB. Perinatal outcomes following implementation of TennCare. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279:314–6.

Waters HR, Hussey P. Pricing health services for purchasers—a review of methods and experiences. Health Policy. 2004;70:175–84.

Obadha M, Chuma J, Kazungu J, Barasa E. Health care purchasing in Kenya: experiences of health care providers with capitation and fee-for-service provider payment mechanisms. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2707.

Wright J, Eichler R. A review of initiatives that link provider payment with quality measurement of maternal health services in low-and middle-income countries. Health Syst Reform. 2018;4:77–92.

Agyei-Baffour P, Oppong R, Boateng D. Knowledge, perceptions and expectations of capitation payment system in a health insurance setting: A repeated survey of clients and health providers in Kumasi, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–9.

Dodoo JNO. Stakeholder analysis of the capitation pilot under Ghana’s national health insurance scheme in the Ashanti Region_2013-1. Ph.D. thesis. 2013.

Capitation. https://www.nhis.gov.gh/capitation.aspx. Accessed 26 Mar 2022.

Andoh-Adjei FX, Nsiah-Boateng E, Asante FA, van der Velden K, Spaan E. Provider preference for payment method under a national health insurance scheme: a survey of health insurance-credentialed health care providers in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:1–13.

Koduah A, Van Dijk H, Agyepong IA. Technical analysis, contestation and politics in policy agenda setting and implementation: the rise and fall of primary care maternal services from Ghana’s capitation policy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:1–14.

Kofi M, Boachie MK, Amporfu E. Association between healthcare provider payment systems and health outcomes in Ghana association between healthcare provider payment systems and health outcomes in Ghana. 2021.

Opoku M, Nsiah R, Oppong PA, Tetteh E. The effect of capitation payment on the national health. J Insur. 2014;28:114–27.

Andoh-Adjei F-X, Boudewijns B, Nsiah-Boateng E, Asante FA, van der Velden K, Spaan E. Effects of capitation payment on utilization and claims expenditure under National Health Insurance Scheme: a cross-sectional study of three regions in Ghana. Health Econ Rev. 2018;8:1–10.

Comfort AB, Peterson LA, Hatt LE. Effect of health insurance on the use and provision of maternal health services and maternal and neonatal health outcomes: a systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(4 SUPPL.2):S81.

Linden A. Using forecast modelling to evaluate treatment effects in single-group interrupted time series analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:695–700.

Awoonor-Williams JK, Bawah AA, Nyonator FK, Asuru R, Oduro A, Ofosu A, et al. The Ghana essential health interventions program: a plausibility trial of the impact of health systems strengthening on maternal & child survival. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:S3.

Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA. The Ghana Community-based Health Planning and Services Initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:25–34.

Kweku M, Amu H, Awolu A, Adjuik M, Ayanore MA, Manu E, et al. Community-based health planning and services plus programme in Ghana: a qualitative study with stakeholders in two Systems Learning Districts on improving the implementation of primary health care. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:1–24.

Amoakoh-Coleman M, Kayode GA, Brown-Davies C, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K, et al. Completeness and accuracy of data transfer of routine maternal health services data in the greater Accra region. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:1–9.

Indicator Metadata Registry Details. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/80. Accessed 26 Mar 2022.

Wemakor A. Prevalence and determinants of anaemia in pregnant women receiving antenatal care at a tertiary referral hospital in Northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:495.

Brosig-koch J, Wiesen D. The effects of introducing mixed payment systems for physicians—experimental evidence #543. 2015.

Brosig-Koch J, Hehenkamp B, Kokot J. The effects of competition on medical service provision. Health Econ UK. 2017;26 July:6–20.

Hennig-Schmidt H, Selten R, Wiesen D. How payment systems affect physicians’ provision behaviour—an experimental investigation. J Health Econ. 2011;30:637–46.

Ponce P, Marcelli D, Guerreiro A, Grassmann A, Gonçalves C, Scatizzi L, et al. Converting to a capitation system for dialysis payment—the Portuguese experience. Blood Purif. 2012;34:313–24.

van Dijk CE, van den Berg B, Verheij RA, Spreeuwenberg P, Groenewegen PP, de Bakker DH. Moral hazard and supplier-induced demand: empirical evidence in general practice. Health Econ. 2013;22:340–52.

Mills A, Bennett S, Siriwanarangsun P, Tangcharoensathien V. The response of providers to capitation payment: a case-study from Thailand. Health Policy. 2000;51:163–80.

Glazier RH, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, Sibley LM. Capitation and enhanced fee-for-service models for primary care reform: a population-based evaluation. CMAJ. 2009;180:72–81.

Pereira AG, Pearson SD. Patient attitudes toward physician financial incentives. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1313–7.

Andoh-Adjei FX, Cornelissen D, Asante FA, Spaan E, Van Der Velden K. Does capitation payment under national health insurance affect subscribers’ trust in their primary care provider? A cross-sectional survey of insurance subscribers in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:1–10.

Atinga RA, Baku AA. Determinants of antenatal care quality in Ghana. Int J Soc Econ. 2013;40:852–65.

Yawson AE, Biritwum RB, Nimo PK. Effects of consumer and provider moral hazard at a municipal hospital out-patient department on Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme. Ghana Med J. 2012;46:200–10.

Aryeetey GC, Nonvignon J, Amissah C, Buckle G, Aikins M. The effect of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) on health service delivery in mission facilities in Ghana: a retrospective study. Glob Health. 2016;12:1–9.

Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, Lévesque LE, Cadarette SM. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:950–6.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the District Director and staff of the Asante Akim North District Directorate of the Ghana Health Service during the data extraction.

Funding

There was no funding for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JKY contributed to the concept and design of the study, development of the data collection instrument, data analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. KAM contributed to the concept and design of the study, development of the data collection instrument, the acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. NK contributed to the concept and design of the study, development of the data collection instrument, acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. RAA, MOB, LK, DO and WQ contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Committee on Human Research Publications and Ethics of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Reference Number CHRPE/AP/426/20).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yambah, J.K., Mensah, K.A., Kuunibe, N. et al. The effect of the capitation policy withdrawal on maternal health service provision in Ashanti Region, Ghana: an interrupted time series analysis. glob health res policy 7, 38 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-022-00271-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-022-00271-1