Abstract

Background

Community Health Workers (CHWs) have been widely used in response to the shortage of skilled health workers especially in resource limited areas. China has a long history of involving CHWs in public health intervention project. CHWs in China called village doctors who have both treatment and public health responsibilities. This systematic review aimed to identify the types of public health services provided by CHWs and summarized potential barriers and facilitating factors in the delivery of these services.

Methods

We searched studies published in Chinese or English, on Medline, PubMed, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and CNKI for public health services delivered by CHWs in China, during 1996–2016. The role of CHWs, training for CHWs, challenges, and facilitating factors were extracted from reviewed studies.

Results

Guided by National Basic Public Health Service Standards, services provided by CHW covered five major areas of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) including diabetes and/or hypertension, cancer, mental health, cardiovascular diseases, and common NCD risk factors, as well as general services including reproductive health, tuberculosis, child health, vaccination, and other services. Not many studies investigated the barriers and facilitating factors of their programs, and none reported cost-effectiveness of the intervention. Barriers challenging the sustainability of the CHWs led projects were transportation, nature of official support, quantity and quality of CHWs, training of CHWs, incentives for CHWs, and maintaining a good rapport between CHWs and target population. Facilitating factors included positive official support, integration with the existing health system, financial support, considering CHW’s perspectives, and technology support.

Conclusion

CHWs appear to frequently engage in implementing diverse public health intervention programs in China. Facilitators and barriers identified are comparable to those identified in high income countries. Future CHWs-led programs should consider incorporating the common barriers and facilitators identified in the current study to maximize the benefits of these programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the global chronic shortage of skilled health workers in the World Health Report [1]. This shortfall of available skilled health workers has been estimated to be as high as 4.25 million in Africa and Asia [1]. The quality and density of human resources for health has been widely considered as one of the main contributors of maternal and child health outcomes and other health inequalities [2, 3]. In the attempt to deal with this health workers crisis, many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have widely used community health workers (CHWs) to support the underserved population in resource-limited settings and deliver key health care and health promotion interventions in their communities [4].

According to WHO, CHWs consist of different community health aides, but not trained health professionals, who are selected and trained to work in their own communities [1]. They are usually trained to deliver various basic and health-related interventions and services within their own community. However, CHWs may have different titles because their specific job responsibilities within their local cultures and health systems vary (e.g., traditional birth attendant, community health volunteer, village health worker, village doctors, health advocates etc.). It is difficult to generalize one universal title for all CHWs [1]. We will use the term “CHWs” to describe all these categories of healthcare workers in this paper, unless specified otherwise.

Evidence from various countries has shown that CHWs are able to make effective contributions in health outcome, particularly in maternal and child health [5,6,7]. One of the best-known programs of CHWs is the “barefoot doctors” which was implemented in China from the 1950s to the early 1980s. Around one million agricultural workers were trained to be the “barefoot doctors” to provide primary health care, first aid, and health education [8]. They significantly improved rural health care coverage and infectious disease control and dramatically reduced the national infant mortality rate [9]. However, in 1981, as the national health system shifted from a cooperative medical system to a private medical system, the barefoot doctor program was abolished [10]. In this private medical system, the “barefoot doctors” still served as frontline healthcare workforce in primary health care level. Their title became “village doctors” if they passed the national exam of the village doctor, or their title became “village health aides” if they failed.

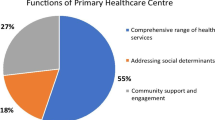

Currently, China’s health system consists of three levels: tertiary, secondary and primary levels (Fig. 1). Tertiary hospitals are responsible for the majority of comprehensive diagnosis and treatment. They have full coverage of diverse medical and surgical departments and are equipped with modern medical and diagnostic equipment. These hospitals exist in large and medium-size cities. Secondary hospitals include general hospitals in small cities and counties of large cities, as well as most specialist hospitals. However, the CHWs only served in primary health care level. Primary health service is provided by medical institutions, which refers to basic level health service institutions in residential areas in urban or rural town health centers. The scale of community health centers varies greatly. In large cities like Shanghai and Beijing, community health centers (CHCs) are developed from some small secondary hospitals with inpatient care. The number of CHWs in each CHC may vary between 5 and 10). Other primary health centers, however, especially health stations in rural areas, only have a limited number of doctors (varies between 1 and 5), the so-called village doctors, to provide basic consultancy services. Generally, the population that each CHW serves ranges from 300 to 2500 residents [2].

In recent years, the Chinese Ministry of Health has started to emphasize more to improve the primary health care services by incorporating the community based services within the primary healthcare system [11, 12]. Since then the function of basic medical service and public health services has been integrated into primary healthcare level (community health services centers). In accordance with the provisions of the National Basic Public Health Service Standards, issued by the Ministry of Health in 2011, community-based health services should include the following aspects: health records, health education, immunization, infant care, maternal care, health management of elderly, health management of patient with hypertension, type II diabetes, mental illness and infectious disease, as well as public health emergencies report and treatment [11, 12]. All of these services are delivered by existing healthcare personnel working in community health centers including CHWs; usually Chinese traditional medicine services are not provided in the community health centers.

Although the village doctors provide both treatment and public health services, they usually focus more on treatment instead of public health service, due to the inadequate financial incentives to deliver public health service and heavy workload [13]. Besides financial incentives, studies in other countries provided evidence that CHWs performances can be affected by recruitment process, workload, and retention policies [14,15,16]. Policies on incentives, career perspectives, and supervision have great influence on CHW’s motivation. In addition, reviews also showed that basic and continuing training and education can enhance CHW’s performance [17,18,19]. However, limited studies were conducted on this frontline workforce of primary healthcare provider in China. Understanding the pattern of services provided by CHWs and the challenges and barriers faced by CHWs will guide the policy makers in assessing the potential to integrate CHWs within primary health care delivery systems. Also, to address shortages of healthcare workforce, many developing countries are now examining the potential to engage CHWs to deliver primary healthcare services. Experiences from China would be useful to guide these countries in developing local policy strategies to integrate CHWs within primary health care delivery systems. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of intervention studies involving CHWs, to identify the types of public health services provided by CHWs and summarized potential barriers and facilitating factors in the delivery of these services. This systematic review will be guided by the following research question: What are the types of public health programs provided by CHWs in China as reported in studies from 1996 to 2006, and what are the barriers and facilitating factors?

Method

Search strategy and procedure

We conducted a systematic review of all manuscripts published in peer-reviewed English and Chinese language journals about the topic of the role of CHWs in primary health service delivery in China. Following a protocol, the literature review began with a search on PubMed, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Academic Journals full-text database) using two combinations of the medical subject heading (MeSH): ‘community health worker’ and ‘China’; ‘village doctor’ and ‘China’. After identifying initial studies, the additional keywords, ‘midwifery’, ‘reproductive health’, ‘family planning’, and Non-communicable diseases like ‘hypertension’, ‘diabetes’, ‘mental’, ‘chronic’, ‘cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)’, ‘stroke’, ‘cancer’, ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPDs)’, ‘physical activity’, ‘obesity’, ‘diet’, ‘tobacco’, ‘smoking’, ‘alcohol’ were used combine with the initial keywords. These keywords were also translated into Chinese when searching Chinese literatures via CNKI. We restricted our review to the manuscripts that were published in the last 20 years (1996–2016). We used the publication date instead of the study date for consistency since publication date is more accessible than the study date. We also used the link to related articles in PubMed and CNKI for initially selected articles. After searching the manuscripts with keywords, the reference lists of these manuscripts were hand-searched to identify additional publications.

Each manuscript was assigned a reference number. Each manuscript includes the title, types of program, terms used to define CHWs, the role of CHWs, program duration, type of training delivered to CHWs, challenges, and facilitating factors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for CHWs-delivered studies included:

-

1.

Participants: Participants can be patients or the general population. We do not have specific requirements for participants since various people could be the receiver of these public health services.

-

2.

Intervention types: Preventive measures or health promotion interventions that were provided by CHWs.

-

3.

Comparison: Not applicable.

-

4.

Outcome: Delivery of reported intervention.

-

5.

Study types: Intervention studies conducted in China which focused on public health services including health education, reproductive health and family planning, managing patients with infectious disease, child health, vaccination, and common NCDs (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer and mental health.

The exclusion criteria included: i) articles that did not focus on China; ii) articles that focused on the health professionals (physicians, doctors, nurses) rather than CHWS as we have defined for this review; and iii) articles that did not describe structured public health interventions (e.g., news, conference reports, books, reviews, health system analysis, disease prevalence).

Data extraction

Using the above inclusion and exclusion criteria, two reviewers (WH and HL) identified relevant studies independently. Each reviewer screened the titles and abstracts of the potential articles to assess their eligibility for this review. When there was disagreement, the decision to include a study was made after discussion and consensus by both reviewers and, in some cases with input from the project leader (ASA). We then read the full texts of all eligible materials and summarized relevant content. Using an Excel form, we assigned each eligible article with a unique reference number and extracted the following information: the types of program, titles of CHWs, the services provided by or/and the responsibilities of CHWs, program duration, training received by CHWs, challenges and facilitators faced by CHWs in the engaged program. We also summarized the training types received by CHWs and the training duration respectively, if this information was available.

Results

General description

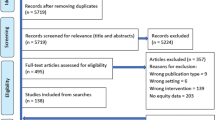

We identified 65 full-text published studies; 43 in English (Table 1) and 22 in Chinese (Table 2) that fit our criteria from 16,473 articles. In Fig. 2 we described the article screening process that followed PRISMA flow diagram [20]. Only one study evaluated a nationwide program [21]. Fifty-one studies (22 in Chinese) were single site studies conducted evenly in east, central, and west China. Thirteen studies (all English) were the multi-site programs that ranged from two to eight sites [22,23,24,25].

In terms of the duration of these programs, a few studies lasted for 2–6 months [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The majority of the studies, including 18 NCD studies lasted more than one year, even a few years [25, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Some others, including a family planning, a mental health, and 4 tuberculosis-related studies evaluated the on-going programs [21, 25, 49,50,51,52].

Most of the studies (18 studies) were related to NCDs covering five major areas of diabetes and/or hypertension [28, 29, 43, 44, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59], cancer (h [45, 46]), mental health [32, 33, 52, 60,61,62,63,64,65], cardiovascular diseases [66,67,68,69]; and NCD health education [47, 70]. Ten articles were related to reproductive health, including family planning, prenatal care, and postnatal care. Besides family planning and maternal health, other services provided by CHWs includes managing patient with infectious disease like tuberculosis (TB) (10 studies), HIV (3 studies), child health (one study provided early childhood development consulting [61] while another study provided counseling for children second-hand smoking exposure [62]), immunization (4 studies [70,71,72]), and others (one study focused on shallow anterior chamber screening [73], one study conducted verbal autopsy [74], and two studies for tobacco control [36, 75]).

The terms used to define CHWs varied in different studies. Most of the studies used village doctors (VDs) or community health workers as CHWs (n = 42). In family planning and maternal health care particularly, traditional birth attendances (TBAs) (n = 2), village/grassroots maternal health care workers (n = 3), traditional village midwives (n = 1), family planning workers/staff (n = 4), outreach providers (n = 1), and village nurses (n = 8) were also used. In those NCD studies, other terms for CHWs include lay family health promoters (n = 2), lay health supporters (n = 1), health coach (n = 1), non-professional health workers (n = 1). In Chinese literature, particularly, community nurses and CHWs were referred in a health management team (n = 5).

Public health services that CHWs provided

Public health services provided by CHWs were various depending on the types of studies and programs. In most of the studies, CHWs served as program recruiter and health aides providing health education and assisting patient management.

NCD related services

In all the identified NCD-related programs CHWs mostly assisted clinicians to promote screening for major NCDs. In some studies, they provided lifestyle modification supports via counseling and educational sessions among NCD patients and people at risk [28, 30, 46, 47, 54, 56, 57, 65,66,67,68, 70]. The content of such counseling support included healthy diet, physical activities, mental health self-management, smoking cessation, salt intake reduction, and practical approaches to prevent unhealthy behaviors. CHWs also helped in monitoring patients’ medication adherence in regular follow-ups, reporting side-effects, and referring severe cases to the higher level medical facilities [29, 44, 52, 58, 59, 65,66,67,68]. In addition, several studies reported that well-trained CHWs with sufficient technical support could distribute mental health medicines [52, 61, 65], measure blood pressure, directly conduct early detections for CVDs or diabetes, as well as prescribe blood pressure lowering drugs and aspirin for CVDs [28, 43, 56, 66,67,68].

Reproductive health

Among the studies that focused on reproductive health, consisting of family planning and maternal health, CHWs mostly provided outreach home visit services [23, 26, 27, 41, 76,77,78]. CHWs also provided health education to pregnant women and their companions on specific topics, including prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections [79], maternal newborn danger sign recognition [41, 76], antepartum and postpartum care seeking and nutrition [27, 41, 76, 78, 80], and breast feeding [76]. They were also in charge of distributing contraceptives, managing and supervising contraceptives as family-planning workers. Other services provided by CHWs included distribution of nutrient supplements for pregnant women [80], conducting mini-survey [80], monitoring compliance of supplements taking [80], and offering general or specific health promotion counseling [23, 25, 27, 78, 81]. Only one study mentioned that CHWs attended births [41].

Infectious diseases (tuberculosis and HIV)

Guided by Directly Observed Treatment, Short Course (DOTS) strategy, the major responsibility of CHWs was to provide direct observations for smear-positive TB patients in most of the studies [21, 24, 37,38,39, 49, 50, 82]. Meanwhile, they detected new TB cases, followed up TB patients, referred patients to higher level TB dispensaries and designated sputum examination centers, as well as conducted relevant surveys or collected relevant data for research teams [51, 82, 83].

Four studies [48, 78, 83, 84], all in Chinese literature, reported using VDs to support HIV prevention. In one study, VDs screened potential TB patients who were living with HIV [78]. In other three studies, VDs and volunteers provided health education on HIV prevention for migrant workers [83], HIV patients and their family [84], and female sex workers [48].

Child health and Vaccination

CHWs provided early childhood development consulting in the two child-health-related studies [61]. In the immunization-related study, CHWs monitored children’s immunization status and reminded their caregivers to get the child vaccinated [22]. In other studies, village-based health workers administered immunization shots using auto-disposable syringe and vaccine storage in rural areas to ensure the timely immunization for Hepatitis B birth-dose [71, 72].

Tobacco control and other services

Two of the tobacco control studies targeted specific population. In those studies, CHWs were responsible for individualized counseling to parents on second hand-smoking exposure to children [62] and to family members of pregnant women on passive smoke exposure to pregnant women [75]. In another study, CHWs provided general tobacco control intervention in the community [67]. In two studies, CHWs played other roles like screening shallow anterior chamber or conducting verbal autopsy based on the research program [73, 74].

Training received by CHWs

Training content

Among all the identified articles, 38 studies indicated the training of CHWs and 34 of these studies reported details of the training content. The content of CHWs’ training was relevant to the services that they would provide. For example, in maternal health-related studies, CHWs usually received training on basic knowledge about maternal health, conducted prenatal visits, and identified danger signs [41]. While for the CHWs who conducted or assisted in NCDs screenings, generally acquired knowledge on the disease-related risk behaviors, how to detect suspicious cases [66, 68], how to screen [67], and the meaning of the positive test [45]. The level of training received by CHWs differed across studies. For example, in a study conducted in Guangxi, the training for TBAs is focused on care during childbirth and referral skills while the training for trained birth attendances (TBAs) included additional midwifery training and conducting of at least 30 independent deliveries under an obstetrician’s supervision [77]. CHWs also received other types of training including health education communication skills [23], computer skills [79], mobile phone app use [22], TB/HIV control and management [40, 82], and verbal autopsy interview skills [74].

Types of training

Seventeen articles described the types of training for CHWs. Most trainings were given by teachers or experts through lectures. In-class and group discussions as well as role-plays were used frequently in CHWs trainings [23, 32, 35, 76]. Some NCD studies also used web-based trainings combined with video, picture, and text for CHWs [28, 43, 46, 64]. Two studies mentioned reflection-action-assessment cycle methods and case review [35, 42]. Besides formal training, one article also delivered desk calendars with TB information and control policy to village doctors, village leaders, and patients [83].

Challenges

Forty seven articles indicated various challenges in the CHWs led projects. The common barriers are: lack of transportation, lack of official support, poor capacity of CHWs, lack of training for CHWs, incentives for CHWs, and establishing and maintaining the relationship between CHWs and target population in the community.

Transportation

Four articles mentioned the challenges in transportation to reach the community [24, 49, 77, 82]. In remote areas, institution-based delivery was hard to perform without proper logistic support [77]. Village doctors also reported that it was hard to launch DOTS with an inconvenient transportation system [24, 49, 82]. Additionally, one literature mentioned that the residency of target population (i.e. migrant workers) in rural areas are scattered [83].

Official support

Official support includes the financial and policy supports from government and the understanding from local stakeholders. In China, policy is a guide for family-planning workers and other government-funded programs. In the study of Tu et al. (2004), family-planning workers were unsure of the need for the government agency providing reproductive health education to unmarried young people [25]. Another study discussed the concerns from local leaders about the utility and appropriateness for involving village health workers with little formal education. These concerns affected the long-term commitment of key trainers to provide training or some CHWs to receive training [42]. One study emphasized the need of government support both on funding and regulations [67]. Another two studies pointed out the need to involve stakeholders such as family planning, civil administration, women’s federation, administration of justice, and public security department [65, 81].

Quantity and quality of CHWs

CHWs usually have heavy workload by providing both their assigned routine duties and public health services at the same time. One of the articles used “shortage of hands” to indicate this barrier [24], reflecting the workloads and demands of their work. Additionally, the village doctors who were already busy in providing general primary healthcare services were reluctant to add extra NCD related tasks on their agenda [43, 52, 61]. On the other hand, some CHWs lacked adequate knowledge and capability to meet the demand of their assigned work [40, 47, 51, 57,58,59]. Other studies also indicated CHW’s lack of specific skills as barriers [24, 42, 51, 58, 59, 70]. One study pointed out that the average age for VDs are getting older [58].

Training of CHWs

The training received by CHWs was diverse and related to various education levels of CHWs, different learning needs, too many trainees, and trainers’ unfamiliarity with the work of CHWs, especially in programs that used technological support [23, 24, 41, 42, 70, 74, 77]. Less than 40% (8 out of 22) of the Chinese literature reported detailed training for CHWs. Most of these trainings were provided as lectures and evaluated by tests. None of the studies discussed the challenges in training CHWs.

Incentives for CHWs

Varieties of motivational factors to engage CHW in public health service delivery was described across studies. Ten articles emphasized inadequate financial incentives for CHWs [23, 24, 30, 34, 37, 40, 49, 65, 82, 83]. Different issues of financial incentives include the shortage of funding [30, 65, 83], lack of subsidies [23], specific allowance/incentives did not reach to CHWs [24, 78, 83], and no additional financial reward [61]. Another article reported lack of recertification mechanism as barrier for motivating CHWs to attend training and learn more medical knowledge [79].

Maintaining relationship between CHWs and target population

The main barrier in maintaining the relationship between CHWs and target population is the mobilization of the target population [34, 40, 70]. Non-permanent job status of CHWs was another barrier to build rapport [41]. Population mobility was a barrier to maintain relationship in programs of TB, HIV and immunization [34, 70]. A study mentioned the difficulties to involve elderly people in the intervention [80].

Facilitating factors

Official support

In China, official support is crucial for CHWs-led health program. Several studies emphasized the official support from government and clinic as a facilitator in their studies [40,41,42, 78]. Similarly, Wei et al. (2008) underlined the importance of the leading role of the local policy maker while making changes in policy and practice in primary health care [82]. The nationwide program used a top-down approach with specific task assignments to CHWs, which was effective in TB control and management [21].

Integration of CHWs programs within the existing health systems

Although CHWs were integrated in the existing health system, a well-designed health intervention program which could be fitted into the current system as the routine task for CHWs was identified as one of the facilitators. A tobacco control study mentioned one of the facilitating factors as incorporating the intervention with the existing pregnancy insurance services system [75]. Edward and Roelofs (2006) emphasized the good fit between core project elements and the existing health system when designing their health intervention project. Deep engagement of local partners was a good approach to ensure effective implementation of the CHW-led program [42]. Jiang et al. (2016) discussed the need for sufficient and comprehensive preparation within the health system in order to develop a well-designed intervention program [77]. These preparations include training of health human resources (i.e. CHWs), building infrastructure, improving services quality, and establishing referral system with quality referral center.

Relationship between CHWs and residents

The good relationship between the CHWs and residents is an important facilitating factor. The team-based model is becoming more common [29,30,31, 33, 38, 48, 65]. The benefit of involving the CHWs in the multidisciplinary health management team is that they can act as a bridge between the team and patients [59]. Because the CHWs always work closely with the community, they can provide intervention conveniently and frequently [48]. Moreover, it is easier for the CHWs to educate the family members of the patient compared to physicians [69, 85].

Financial support

Four articles mentioned financial support as a facilitator for CHWs engagement in healthcare delivery [24, 37, 40, 77]. Financial compensation for CHWs was provided by local health institutions based on the services that they provided (i.e. the number of pregnant woman escorted to the health institute) [77]. They could also receive additional payment if they provided other services, including prenatal/postpartum examination referral to a health facility [77]. One study suggested non-monetary incentives like food, uniform or public praise as substitutes to cash allowance [24]. Few studies suggested that performance-based incentives were effective in increasing CHWs’ job motivation and improving their work performance [43, 46, 67, 68].

Technology support

Overall, ten studies used the website or mobile phone applications to facilitate CHWs-led programs. Seven of them were NCD-related [24, 46, 55, 57, 64, 66, 68] and only three studies were related to general service provision [22, 74, 79]. One study used the website as a training method to provide specific training for village doctors [79]. Another study used a mobile phone-based application to support health management system in improving immunization management and tracking by CHWs [22]. Zhang et al. used mobile phone-based application to facilitate decision support system for verbal autopsy interviews by CHWs [74].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that provides a critical appraisal of health programs delivered by CHWs in China during the last two decades. We found that, overall, CHWs provided varieties of services that were relevant to the national policy for basic public health services and the national priority public health programs. We found that family planning and reproductive health services were more frequently being studied and reported in the review. It could be partially explained by the family planning policy initiated in 1983 that required the National/State Ministry of Health and Population and Family Planning Commission working closely with local CHWs and village doctors [86]. Similarly, CHWs were also engaged in the implementation of national programs of DOTS [87] and Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) which was initiated in 2008 [88]. These engagement of CHWs in major national programs suggests that the government realized the importance of CHWs in promoting public health programs underscoring the potential for their integration into the existing primary healthcare systems. In programs where CHWs were engaged to work in specific project with funding for limited duration [62], extra efforts need to be made to keep these CHWs engaged in the same community based programs, if the program proven to be effective.

We found that there was no consistency in terms of duration and intensity of the training received by CHWs in the studies reviewed since most of the trainings were on-the-job training (i.e. specific trainings were given in relation to specific tasks). While this is understandable that the training was customized to the needs of the specific program, a basic training on core competencies would improve the quality of the service delivery and the overall skills of CHWs. Earlier studies reported several barriers in relation to the training of CHWs, including relatively low educational levels of CHWs [42], too many trainees while a few available trainers [23], and technology usage in the training for elderly CHWs [70]. In the current study, we also identified similar barriers for training CHWs, which underscore the importance of considering these in the planning of any training for CHWs.

One of the crucial factors for CHWs to implement programs effectively was the level of official support received from the national and local government as well as other stakeholders. Essentially, the support from the government could be both a barrier and a facilitator. In our review, studies found that ambiguous policies and perspectives from local leaders could impede CHWs implementing health intervention programs. However, if the health intervention program could receive the official support from government and health centers, these supports would be great facilitators [41, 42]. In China, using a top-down approach turned out to be effective for many nationwide health programs (e.g. Patriotic Sanitation Campaign started from 1952). With a specific policy or working guide, CHWs would have a proper perspective of the provision of primary health services. Moreover, the government is responsible for the construction of infrastructure including improving transportation system and building community health centers and village clinics. Road accessibility was one of the basic requirement for proper logistic support, particularly in rural areas and remote villages [77]. The convenient transportation system was needed for CHWs to effectively launch DOTS strategy, either for patients coming to the CHW’s office or for the CHW’s visit to patients’ home [24, 49, 82].

In the studies reviewed, we identified several factors that were relevant in keeping CHWs motivated to their job. These included reduced workload, financial and non-financial incentives, regulation and continuous education, integration of CHWs in the current health system, and the job satisfaction of CHWs. These factors are consistent with previous findings in low- and middle- income countries [89]. In earlier studies, village doctors were most dissatisfied with their pay and the amount of work, as well as promotion and work conditions [90, 91]. Few other studies also reported that low salary and lack of financial incentives were substantial barriers for motivating CHWs [24, 34, 83]. Thus, appropriate financial incentives system is valuable for the whole health-care system to retain CHWs in their existing jobs [89].

Information and communication technologies or mHealth (i.e. internet, mobile phone applications) was frequently used in recent years by the researchers in CHWs delivered programs. It could be an effective approach to improve the consistency and efficiency of health services delivery by CHWs [92, 93]. Although only three studies used website and mobile phone applications in general service provision, the outcomes were promising [22, 74, 79]. For example, in the study of Chen et al. (2016), the use of Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) application improved the local full vaccination coverage and working efficiency of CHWs [22]. This finding is consistent with a previous systematic review on CHWs and mobile technology, which indicated that new technologies could assist CHWs to improve the quality of providing health services, the efficiency of health intervention, and capacity for program monitoring [92]. One of the barriers mentioned in reviewed studies was the elderly CHWs as they might not familiar with smart phone applications or not willing to learn about new technology. Future studies could focus on developing user-friendly applications and should plan to provide multiple training for elderly CHWs.

To ensure the sustainability of the health intervention program, China benefits form its institutionalization of CHWs as part of the primary healthcare providers (VDs and community nurses). This is similar to the program in Brazil, the Brazilian Family Health Programmer, which integrated CHWs into its health services and institutionalized community health committees to ensure the sustainability of health care delivery [94]. Both China and Brazil also benefit from the multidisciplinary health care team in the primary care setting, which may include CHWs, psychiatrists, general practitioners, nutritionists, public health specialist, and others.

Unlike the high-income countries, where CHWs mainly focus on marginalized population [95], Chinese CHWs provides health care services for all members in the community, based on the programs to which they are assigned. Therefore, the potential to generalize and expand the CHWs-led programs in China is great and should be explored further.

Public health implications

The findings of this review have several implications.

Motivation of CHWs and health-care reform

The motivation of CHWs to engage in public health service delivery was influenced by the whole range of health sector reform [96]. In 2009, a new health-care reform was launched aiming to achieve universal health coverage. This health-care reform dramatically reduced the income of village doctors by canceling the drug mark-ups which was the primary source of income for village doctors for more than a decade [97, 98]. Realizing the irreplaceable role of CHWs and the lack of financial incentives for primary health services, Chinese Ministry of Health issued the National Basic Public Health Service Standards as a guideline for primary health services in 2011. The Ministry of Health also increased the compensation for primary health services per capita in recent years. However, the compensation was still insufficient and sometimes even did not reach to the CHWs [97]. In 2015, the average compensation for basic public health services per person increased from 35 to 40 RMB (1US$ = 6.90RMB). Measures need to be taken so that the increased compensation would reach to CHWs to motivate them in the delivery of primary health services. However, the effectiveness of this new policy hasn’t been evaluated.

In terms of the incentive mechanism, Tao et al. (2013) suggested that performance-based incentive could be an effective approach to improve the performance of CHWs in tuberculosis DOTS strategy [24]. However, a systematic review by Kok et al. (2015) indicated that this approach could sometimes lead to ignore the unpaid task of CHWs’ daily work [99]. Although pay-for-performance has become popular in recent years to initially improve the performance of health professionals while controlling healthcare expenditure, policy makers should carefully design the payment system to reach their initial goals in China [100]. To provide more evidence for policy makers, future research studies could focus on exploring and evaluating salary and incentive mechanisms which could effectively motivate CHWs and improve health care service quality as well as the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Ensure long-term commitment of CHWs

In China, CHWs were part of the primary health care system, whose salary were covered by the government. However, engaging these CHWs in primary health care with long-term commitment may be not easy. The long-term commitment of CHWs in the primary health-care system is a prerequisite for sustainable health intervention program engaging CHWs. This long-term commitment could greatly be influenced by regulation and continuing education for CHWs. These two factors could help village doctors building long-term perspectives of their career and motivate them to keep learning and practicing in primary health care.

A regulation for CHWs issued in 2003 called the Regulation on the Administration of the Practice of Rural Doctor, which took effect in 2004 [101]. The registration system in this regulation requires village doctors to be trained by local health department at the county level. After the training, village doctors must pass the license examination to be qualified. The challenge to execute the regulation is the low educational level of the current village doctor. Although the national continuing medical education system requires professional physicians and nurses in the township or higher level to attend training and take an exam, it does not have corresponding requirements for village doctors. Other than the 2005’s regulation, there are neither relevant regulations nor financial support for continuing medical education and promotion for village doctors.

Since there are no systematic and professional continuing education for CHWs regulated by the government, these trainings were mainly based on the different needs of the health intervention programs. However, this should be noted that the training process for CHWs was rarely described in reviewed studies while few earlier studies had ever explored the effective training for CHWs. The training for CHWs could be a valuable reference when designing similar primary health care intervention program in future studies as well as offering evidence for policy makers to designing continuing medical education for CHWs. Thus, researchers should highlight the importance of CHWs training when designing health intervention programs involving CHWs in the future.

Limitations

A few limitations of this review should be noted. First, because many terms are used to describe CHWs and front-line public health workers, it is possible that we were not able to extract all relevant articles in the existing literature. However, to avoid this, we conducted a systematic electronic search using a comprehensive list of Medical Subject Headings terms as well as similar keywords, such as village doctors or lay health worker, after a consultation with a community health advocate in China and a trained health science librarian. Second, we included both English and Chinese literature. However, most Chinese literature did not discuss the challenges and facilitating factors of their intervention program. Thus, the challenges and facilitating factors were mainly extracted from the English literature. Third, most of the studies reviewed were conducted in rural areas in China. The ethnic and cultural diversity across China limits the generalizability of the findings to all the provinces and cities [25]. Fourth, the findings we summarized are based on the reports in the published paper. No attempts were made to assess the quality of the published reports or to validate the findings or conclusions of the reported studies. Finally, we did not take effort to identify grey literatures and might have missed studies as a result. Therefore, the findings of the current paper need to be extrapolated considering these limitations.

Conclusion

Involving CHWs in the delivery of public health programs has a long history in China. We found that a significant amount of research was conducted in China that involved CHWs. This review has provided insights into the pattern of public health services provided by CHWs in China and summarized potential barriers and facilitating factors. This will allow policy makers and other stakeholders to determine how to engage CHWs to address the growing need for public health services and community based care for diverse healthcare needs. As China is going through healthcare reform, incorporating CHWs as a member of the primary healthcare workforce within the healthcare delivery systems, with enhanced training and continuing training, will motivate CHWs to engage and deliver high standard community-based healthcare services.

Abbreviations

- CHW:

-

Community Health Worker

- DOTS:

-

Directly Observed Treatment, Short Course

- EPI:

-

Expanded Program on Immunization

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- RCT:

-

randomized control trial

- TB:

-

tuberculosis

- TrBAs:

-

Trained birth attendances

- VDs:

-

village doctors

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. The world health report: 2006: working together for health. 2006 [cited 2017 Jan 8]; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43432.

Anand S, Fan VY, Zhang J, Zhang L, Ke Y, Dong Z, et al. China’s human resources for health: quantity, quality, and distribution. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1774–81.

Anand S, Bärnighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet. 2004;364(9445):1603–9.

Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, Boufford JI, Brown H, Chowdhury M, et al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1984–90.

Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2121–31.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Libr [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 Jan 8]; Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3/full.

Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: an integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):11–20.

Sidel VW. The barefoot doctors of the People’s republic of China. N Engl J Med. 1972;286(24):1292–300.

Mathers N, Huang Y. The future of general practice in China: from ‘barefoot doctors’ to GPs? Br J Gen Pract. 2014 Jun;64(623):270–1.

De Geyndt W, Zhao X, Liu S. From barefoot doctor to village doctor in rural China. 1992 [cited 2017 Jan 9]; Available from: http://www.popline.org/node/324436.

Chen Z. Launch of the health-care reform plan in China. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1322–4.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the publishing of health system reform key implementation plan in recent years (2009–2011) [internet]. 2009 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-04/07/content_1279256.htm.

McConnell J. Barefoot no more. Lancet. 1993 May 15;341(8855):1275.

Campbell C, Scott K. Retreat from Alma Ata? The WHO’s report on task shifting to community health workers for AIDS care in poor countries. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(2):125–38.

Jaskiewicz W, Tulenko K. Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: a review of the influence of the work environment. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10(1):1.

Prasad B, Muraleedharan V, et al.. Community health workers: a review of concepts, practice and policy concerns. Rev Part Ongoing Res Int Consort Res Equitable Health Syst CREHS [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2017 Jan 9]; Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.551.4785&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Glob Health Workforce Alliance. 2010;1:249–61.

Hermann K, Van Damme W, Pariyo GW, Schouten E, Assefa Y, Cirera A, et al. Community health workers for ART in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from experience–capitalizing on new opportunities. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(1):1.

Palazuelos D, Ellis K, DaEun Im D, Peckarsky M, Schwarz D, Farmer DB, et al. 5-SPICE: the application of an original framework for community health worker program design, quality improvement and research agenda setting. 2013 [cited 2017 Jan 9]; Available from: http://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/11180460.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

China Tuberculosis Control Collaboration. Results of directly observed short-course chemotherapy in 112 842 Chinese patients with smear-positive tuberculosis. Lancet. 1996;347(8998):358–62.

Chen L, Du X, Zhang L, van Velthoven MH, Wu Q, Yang R, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone app on improving immunization of children in rural Sichuan Province, China: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):909.

Hemminki E, Long Q, Zhang W-H, Wu Z, Raven J, Tao F, et al. Impact of financial and educational interventions on maternity care: results of cluster randomized trials in rural China, CHIMACA. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(2):208–21.

Tao T, Zhao Q, Jiang S, Ma L, Wan L, Ma Y, et al. Motivating health workers for the provision of directly observed treatment to TB patients in rural China: does cash incentive work? A qualitative study. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2013;28(4):e310–24.

Tu X, Cui N, Lou C, Gao E. Do family-planning workers in China support provision of sexual and reproductive health services to unmarried young people? Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(4):274–80.

Sun YY, Ma AG, Yang F, Zhang FZ, Luo YB, Jiang DC, et al. A combination of iron and retinol supplementation benefits iron status, IL-2 level and lymphocyte proliferation in anemic pregnant women. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(4):513–9.

Ma AG, Schouten EG, Sun YY, Yang F, Han XX, Zhang FZ, et al. Supplementation of iron alone and combined with vitamins improves haematological status, erythrocyte membrane fluidity and oxidative stress in anaemic pregnant women. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(11):1655–61.

Chen P, Chai J, Cheng J, Li K, Xie S, Liang H, et al. A smart web aid for preventing diabetes in rural China: preliminary findings and lessons. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e98.

Hui REN, Xiao-ming SUN, Hua FU, Pin-pin ZHENG, Xue-qi GU, Jing XU, et al. Impact of redesigned helth delivery sytem based on the chronic disease care model on quality of hypertensive health care in community. Chin J Health Educ. 2016;32(3):245–8.

Liang C, Jun C, Qi Y. Community Intervention for Patients Who are Recovering after Breast Cancer Surgery. [Chinese]. World Clin Med. 2016;10(5):7-8.

Ling D, Wang L. Application of peer education to transitional care of kidney cancer patients after radical resection. J Nurs Sci. 2014;29(9):78–81.

Tang X, Yang F, Tang T, Yang X, Zhang W, Wang X, et al. Advantages and challenges of a village doctor-based cognitive behavioral therapy for late-life depression in rural China: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137555.

Jiang Y, Jun C, Wei-bo Z, Fang F. Effects of programmed skill training in community on recovery in patients with schizophrenia:one year follow up [Chinese]. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;25(5):312–4.

Jin XM, Sun YJ, Jiang F, Shen XM. Feasibility of the programme of focusing on early childhood development in impoverished rural areas in China. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2005;85(26):1816–9.

Abdullah AS, Hua F, Khan H, Xia X, Bing Q, Tarang K, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure reduction intervention in Chinese households of young children: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(6):588–98.

Li J, Xie J. The effect of community intervention on KAP of smoking among residents of a Community in Tianjin. Chin J Prev Control Chronic Dis. 2010;1:74–5.

Lin W, Liu J, Lai Y, Ma S, Zhen X. Effectiveness of VDs manage TB/HIV dual infection patients. Chin J Public Health. 2011;27(4):396–7.

Li Y. Knowledge of TB prevention and adherence of TB patients in shanghai. Chin Prim Health Care. 2016;30(3):65–6.

Wu B, Yu Z, Yu Y, Huang L, Zhang W. Study on raising awareness rate of tuberculosis knowledge in rural areas by village doctors. Chin J Antituberc. 2015;37(3):285–90.

Chen X, Hu H’a, Li X, Song L, Zhang Y, Zheng J, et al. A feasible study of village doctors AIDS prevention and control works in rural area. Chin Prim Health Care. 2010;24(7):55–6.

Levi A, Factor D, Deutsch K. Women’s empowerment in rural China. Nurs Womens Health. 2013;17(1):34–41.

Edwards NC, Roelofs SM. Sustainability: The elusive dimension of international health projects. Can J Public Health. 2006;97:45–9. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41994677. Accessed 2 Apr 2017.

Feng R, Li K, Cheng J, Xie S, Chai J, Wei P, et al. Toward integrated and sustainable prevention against diabetes in rural China: study rationale and protocol of eCROPS. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13(1):28.

Lin C-W, Abdul SS, Clinciu DL, Scholl J, Jin X, Lu H, et al. Empowering village doctors and enhancing rural healthcare using cloud computing in a rural area of mainland China. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2014;113(2):585–92.

Belinson JL, Wang G, Qu X, Du H, Shen J, Xu J, et al. The development and evaluation of a community based model for cervical cancer screening based on self-sampling. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(3):636–42.

Chai J, Shen X, Feng R, Cheng J, Chen Y, Zha Z, et al. eCROPS-CA: a systematic approach toward effective and sustainable cancer prevention in rural China. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):233.

Li B. Evaluation on the effect of health education intervention to comprehensive knowledge and behavior of chronic diseases in rural Community of Anyang County. Prev Med Trib. 2007;13(5):396–8.

Xuejiang X, Le H, Bing L, Nan H, Ying L, Xiaoyang Z, et al. Effect Evaluation of the AIDS Intervention Mode among Female Sex Workers Based on Community Health Services. [Chinese] Sichuan J Anat. 2016;24(2):37–40.

Meng Q, Li R, Cheng G, Blas E. Provision and financial burden of TB services in a financially decentralized system: a case study from Shandong, China. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2004;19(S1):S45–62.

Sun Q, Meng Q, Yip W, Yin X, Li H. DOT in rural China: experience from a case study in Shandong Province, China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(6):625–30.

Gai R, Xu L, Wang X, Liu Z, Cheng J, Zhou C, et al. The role of village doctors on tuberculosis control and the DOTS strategy in Shandong Province, China. Biosci Trends [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2017 Feb 8];2(5). Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=18817815&AN=42857312&h=CoxImu20bXlXExU2PCEo1dSnkrodIx6xslIDc9URpzuqoDNPviyaPQJtWGSsQMV5zSvkWXoe8QKr5hO3smO5pQ%3D%3D&crl=c.

Ma Z, Huang H, Chen Q, Chen F, Abdullah AS, Nie G, et al. Mental health services in rural China: a qualitative study of primary health care providers. BioMed Res Int [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 May 4];. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2015/151053/abs/.

Li T, Lei T, Xie Z, Zhang T. Determinants of basic public health services provision by village doctors in China: using non-communicable diseases management as an example. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):42.

Browning C, Chapman A, Yang H, Liu S, Zhang T, Enticott JC, et al. Management of type 2 diabetes in China: the happy life Club, a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial using health coaches. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009319.

Peiris D, Sun L, Patel A, Tian M, Essue B, Jan S, et al. Systematic medical assessment, referral and treatment for diabetes care in China using lay family health promoters: protocol for the SMARTDiabetes cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):116.

Zhong X, Wang Z, Fisher EB, Tanasugarn C. Peer support for diabetes Management in Primary Care and Community Settings in Anhui Province, China. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(Suppl_1):S50–8.

Qiao W, Ni M, Luan J, Bao Y. Influence of village clinic construction on control effect in rural patients with diabetes. Occup Health. 2014;18:039.

Ji J. The effect of rural doctors on the control of diabetes mellitus was carried out by the follow-up work. World Latest Med Inf. 2015;45:188.

Chen C, Li H. Effectiveness of health intervention among rural middle and old aged hypertension patients in Shandong province. Chin J Public Health. 2016;32(6):732–5.

Prince M, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Albanese E, Arizaga R, Dewey M, et al. The protocols for the 10/66 dementia research group population-based research programme. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):165.

Gong W, Xu D, Zhou L, Brown HS III, Smith KL, Xiao S. Village doctor-assisted case management of rural patients with schizophrenia: protocol for a cluster randomized control trial. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):13.

Chen M, Wu G, Wang Z, Yan J, Zhou J, Ding Y, et al. Two-year prospective case-controlled study of a case management program for community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2014;26(3):119.

Zhou B, Gu Y. Effect of self-management training on adherence to medications among community residents with chronic schizophrenia: a single-blind randomized controlled trial in shanghai, China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2014;26(6):332–8.

Xu DR, Gong W, Caine ED, Xiao S, Hughes JP, Ng M, et al. Lay health supporters aided by a mobile phone messaging system to improve care of villagers with schizophrenia in Liuyang, China: protocol for a randomised control trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010120.

Shu D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of community complex intervention for severe psychotic patients. Pract Prev Med. 2013;20(8):1016–7.

Ajay VS, Tian M, Chen H, Wu Y, Li X, Dunzhu D, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of a simplified cardiovascular management program in Tibet, China and Haryana, India: study design and rationale. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):924.

Yan LL, Fang W, Delong E, Neal B, Peterson ED, Huang Y, et al. Population impact of a high cardiovascular risk management program delivered by village doctors in rural China: design and rationale of a large, cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):345.

Tian M, Ajay V, Dunzhu D, Hameed S, Li X, Liu Z, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a simplified multifaceted management program for individuals at high cardiovascular risk (SimCard trial) in rural Tibet, China, and Haryana, India. Circulation. 2015;132:815–24.

Fei G, Wen-ying G, Hong-ping Z. Honglei-HU. Effect of rish factors management on intervention of cardiovascular disease in commintty 临床荟萃. 2007;22(21):1543–5.

Li N, Yan LL, Niu W, Yao C, Feng X, Zhang J, et al. The effects of a community-based sodium reduction program in rural China–a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0166620.

Wang L, Li J, Chen H, Li F, Armstrong GL, Nelson C, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination of newborn infants in rural China: evaluation of a village-based, out-of-cold-chain delivery strategy. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):688–94.

Zhang J, Zou G, Dong J, Zhang X, Liu C, Zhang X, et al. Research on strategy of improving the first hepatitis B vaccine inoculation rate of children living in village regions in Longshan County. Chin J Vaccine Immun. 2005;11(2):96–9.

Nuriyah Y, Ren X, Jiang L, Liu X, Zou Y. Comparison between ophthalmologists and community health workers in screening of shallow anterior chamber with oblique flashlight test. Chin Med Sci J. 2010;25(1):50–2.

Zhang J, Joshi R, Sun J, Rosenthal SR, Tong M, Li C, et al. A feasibility study on using smartphones to conduct short-version verbal autopsies in rural China. Popul Health Metr [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 6];14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4992268/.

Wu X, Luo C, Zhao Y, Yan Q, Yao H, Yu J, et al. Effect evaluation of intervention program to reduce passive smoke exposure among 3240 pregnant women in shanghai. J Environ Occup Med. 2014;31(10):770–5.

Dickerson T, Crookston B, Simonsen SE, Sheng X, Samen A, Nkoy F. Pregnancy and village outreach Tibet: a descriptive report of a community-and home-based maternal-newborn outreach program in rural Tibet. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2010;24(2):113–27.

Jiang H, Qian X, Chen L, Li J, Escobar E, Story M, et al. Towards universal access to skilled birth attendance: the process of transforming the role of traditional birth attendants in rural China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):58.

Guo C. Evaluating the effectiveness in community women health through health education and nursing intervention. Chin J Mod Drug Appl. 2014;8(19):209–10.

Tang S, Tian L, Cao WW, Zhang K, Detels R, Li VC. Improving reproductive health knowledge in rural China—a web-based strategy. J Health Commun. 2009;14(7):690–714.

Zeng L, Cheng Y, Dang S, Yan H, Dibley MJ, Chang S, et al. Impact of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight, duration of gestation, and perinatal mortality in rural western China: double blind cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2001.

Qian S. Effect of Community Health Education and Nursing for Improving Women’s Health. Hei Long Jiang Med J [Chinese]. 2013;37(11):1149-50.

Wei X, Walley JD, Liang X, Liu F, Zhang X, Li R. Adapting a generic tuberculosis control operational guideline and scaling it up in China: a qualitative case study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):260.

Xiong CF, Fang Y, Zhou LP, Zhang XF, Ye JJ, Li GM, et al. Increasing TB case detection through intensive referral of TB suspects by village doctors to county TB dispensaries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(9):1004–7.

Duan S, Xiang L, Zhang B, Duan Q, Ye R, Sen Y, et al. Health care Model Base on family and Community for People Living with HIV/AIDS in rural area. Soft Sci Health. 2006;20(1):35–6.

Yang H, Li Y, Qian C, Zhang X, Zhang W, Shi A. Analysis on the effect of companions on health promotion of poor pregnant women in rural areas. Matern Child Health Care China. 2011;26(12):1775–7.

Attane I. China’s family planning policy: an overview of its past and future. Stud Fam Plan. 2002;33(1):103–13.

Reichman LB. Tuberculosis elimination--what’s to stop us? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997 Feb;1(1):3–11.

2004 International Review of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in China [Internet] WHO; 2004 [cited 2017 Jun 29]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/immunization/documents/CHN_Intl_EPI_Review04/en/.

Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, Broerse JE, Kane SS, Ormel H, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low-and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(9):1207–27.

Fang P, Liu X, Huang L, Zhang X, Fang Z. Factors that influence the turnover intention of Chinese village doctors based on the investigation results of Xiangyang City in Hubei Province. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):84.

Li L, Hu H, Zhou H, He C, Fan L, Liu X, et al. Work stress, work motivation and their effects on job satisfaction in community health workers: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e004897.

Braun R, Catalani C, Wimbush J, Israelski D. Community health workers and mobile technology: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65772.

Kallander K, Tibenderana JK, Akpogheneta OJ, Strachan DL, Hill Z, Ten Asbroek AHA, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) approaches and lessons for increased performance and retention of community health Workers in low- and Middle-Income Countries: a review. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2017 Apr 13];15(1). Available from: http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC3636306.

Macinko J, Harris MJ. Brazil’s family health strategy—delivering community-based primary care in a universal health system. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2177–81.

Najafizada SAM. Community health workers in Canada and other high-income countries: a scoping review and research gaps. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(3):E157.

Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(8):1255–66.

Ding H, Sun X, Chang W, Zhang L, Xu X. A comparison of job satisfaction of community health workers before and after local comprehensive medical care reform: a typical field investigation in Central China. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73438.

Zhang S, Zhang W, Zhou H, Xu H, Qu Z, Guo M, et al. How China’s new health reform influences village doctors’ income structure: evidence from a qualitative study in six counties in China. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):26.

Kok MC, Kane SS, Tulloch O, Ormel H, Theobald S, Dieleman M, et al. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Health Res Policy Syst [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Apr 29];13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4358881/.

Wang H, Zhang L, Yip W, Hsiao W. An experiment in payment reform for doctors in rural China reduced some unnecessary care but did not lower Total costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Jan 12;30(12):2427–36.

Regulation on the Administration of the Practice of Rural Doctor [Internet]. May 8, 2003. Available from: http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?lib=law&id=3060&CGid=&EncodingName=gb2312. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Li T, Lei T, Xie Z, Zhang T. Determinants of basic public health services provision by village doctors in China: using non-communicable diseases management as an example. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Mar 5];16(1). Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/16/42.

Wan X, Zhou M, Tao Z, Ding D, Yang G. Epidemiologic application of verbal autopsy to investigate the high occurrence of cancer along Huai River basin, China. Popul Health Metr [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 Mar 5];9(1). Available from: http://pophealthmetrics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-7954-9-37.

Acknowledgments

This paper, as part of the outputs emanating from the Research Hub of Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (APO) hosted by the Global Health Research Center of Duke Kunshan University and funded by the World Health Organization (Purchase Order 201710952). The Research Hub consists of several universities in Asia-Pacific countries. The authors of the paper appreciate technical and financial supports from the Research Hub and the secretariat of APO in the completion of the project upon which the paper was developed. We also want to thank Professor Shenglan Tang of Duke Global Health Institute and Duke Kunshan University for his insights during the implementation of the current study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, the World Health Organization (WHO) (Purchase Order 201710952). The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper. Additional data could be available upon request to the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASA planned the study and oversee the review process. WH and HL conducted the reviews, collected review articles and summarized the findings. JL, TS and PZ helped to update the review papers and commented on the final draft. WH prepared the first draft, which was then distributed to all the co-authors for comments. PZ checked the Chinese literature. All authors approved the final draft of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

As this was a review study no ethics committee approval was required.

Consent for publication

All authors provided consent for this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, W., Long, H., Li, J. et al. Delivery of public health services by community health workers (CHWs) in primary health care settings in China: a systematic review (1996–2016). glob health res policy 3, 18 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-018-0072-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-018-0072-0