Abstract

Increasing interest has been shown in using video games as an educational resource due to their pedagogical possibilities and their current expansion as an entertainment activity. However, their use in schools is still far from mainstream practice, which could be because of the barriers such as the price of video games, schools’ technological infrastructures and teachers’ attitudes. This article focuses on pre-service primary school teachers’ attitudes (future primary school teachers currently studying at university) towards collaborative learning with video games, which employs video games in collaborative learning activities. Because playing video games is a common form of entertainment for higher education students, we investigate whether pre-service teachers’ attitudes are influenced by their experience of playing video games (taking into account the number of years they have played video games), the frequency at which they play video games and their gender. This study takes a quantitative approach, using a questionnaire with a 5-point Likert attitude scale. The results indicate that pre-service primary teachers have a positive attitude towards collaborative learning with video games. Furthermore, students who have played video games for more years, who play more frequently and the male students have more positive attitudes to using video games in collaborative learning activities. Overall, pre-service teachers have positive attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games, which could affect the use of these resources in educational practices. As the main characters in the educational process, both teachers and children need to be comfortable with new practices to achieve the objective of the educational system, which is the complete formation of children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Video games are one of the most popular forms of entertainment today, played by ever-increasing numbers of children, youths and adults on game consoles, computers, smartphones and tablets. In Europe, 25.4% of adults play video games regularly (AEVI, 2011) and a similar percentage of adults (24%) regularly play video games in Spain. The total number of video gamers worldwide was estimated at 1.8 billion in 2015 (Statista, 2016). Furthermore, the game industry has grown significantly, considering that this market was valued at 996 million euros in Spain and the global market raised 71.6 billion euros in 2014 (AEVI, 2015). According to Newzoo (2016), the global market will grow to 99.6 billion dollars (91.7 billion euros) in 2016, and it is predicted to reach 118.6 billion dollars (109.2 billion euros) by 2019.

However, despite the educational benefits of video games found in research, the use of video games in schools is still far from mainstream practice because of barriers to the adoption of video games for learning in the classroom. The barriers include the price of video games, teachers’ attitudes towards using video games, schools’ technological infrastructures, economic crises and a lack of support from the educational institutions or regional and national governments. In particular, this article focuses on pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards the use of video games in collaborative learning activities.

Types of studies about the use of video games in education

There is increasing interest in using video games as an educational resource. According to Van Eck (2006), various studies have examined the use of digital game-based learning by incorporating video games into the learning process in different ways: (1) students create video games, (2) teachers and developers create educational video games to teach the students and (3) commercial video games are used in the classroom. Additionally, while considering the different levels of the educational system, such as primary, secondary and higher education, Martín, Basilotta and García-Valcárcel (2016) classified studies focusing on video games and education into the following three main categories: (1) the use of video games created by companies, developers or institutions, whether ‘Games for entertainment’ (Meyer & Sørensen, 2009) or serious games (e. g. educational games); (2) the analysis of the educational possibilities of using specific video games in the classroom and educational proposals (but without using the video game in the real context) and (3) the creation of video games by students, teachers or both in collaboration.

Based on these classifications (Van Eck, 2006; Martín, Basilotta & García-Valcárcel, 2016), we organised the literature into four groups to summarise the existing studies:

-

(1)

Students create video games to learn something.

-

(2)

Teachers and developers create serious games (e.g. educational games) to teach the students (and these video games are used in education).

-

(3)

Games designed for entertainment are used in the classroom.

-

(4)

Analysis of the educational possibilities of specific video games and educational proposals.

Following this classification, we give some examples of the different studies from each category in Table 1, taking into account the educational level.

As Table 1 shows, a considerable amount of literature focuses on video games and education. While various approaches and educational methodologies have been proposed and used (e.g. individual play or collaborative play; video games as main resource or video games to support classroom learning; use of video games only in classroom time or also at home), our work focuses on collaborative learning.

Collaboration is an essential skill nowadays, and thus collaborative learning needs to be promoted in our schools. In fact, there are many advantages in terms of educational and learning gains of this approach: learning of concepts; development of skills and attitudes; increase of students’ motivation; improvement of students’ self-esteem and self-confidence; knowledge of students’ own learning style; and increase of friendship between students (Barkley, Cross, & Major, 2007; Calzadilla, 2002; Carrió, 2007; Martín-Moreno, 2004; and Scagnoli, 2006).

Regarding video games and collaboration, Yang (2015), based on a review of the literature, made the following suggestions for the effective integration of digital game-based learning: the use of collaboration, the provision of learning aids, scaffolding of learning and instructor orchestration, and a blended learning environment. Yang (2015) highlighted that collaboration is essential if teachers or educators want to promote learning and higher order thinking, such as critical reflection, problem-solving, reasoning and questioning, through online learning environments. Furthermore, there is interest in the possibilities and advantages of the combination of video games and collaborative learning, as it shows in Video Game-Supported Collaborative Learning or VGSCL approach (Padilla, González, & Gutiérrez, 2009) or collaborative game-based learning approach (Romero et al., 2012). Also, these authors (Padilla, González & Gutiérrez, 2009; Romero et al., 2012) highlight that these approaches allow collaborative ‘learning by doing’, enhance learning and allow us to obtain the advantages from both activities, playing and collaborating. In fact, Padilla, González, Gutiérrez, Cabrera, and Paderewski (2009) propose a set of recommendations to design educational video games with collaborative learning activities, taking into account some of the factors required to make collaborative learning more effective, such as positive interdependence, personal accountability, social skills or group processing.

We therefore focus on the approach called ‘collaborative learning with video games’, which refers to the implementation of educational activities in which students work together in pairs or groups, sharing responsibilities, negotiating, discussing and contributing their ideas to achieve an objective (e.g. a project, a task, or to solve a problem) and the main resource of the activity is a video game. In other words, ‘collaborative learning with video games’ refers to the use of video games in collaborative learning activities, in which the collaboration between peers can occur inside the game, outside the game or both, depending on the activity or the methodological strategy used by the teacher. In that sense, Martín (2015) conducted a systematic review of studies related to the collaborative learning approach with video games in Primary Education, taking into account that the studies used a pre- and post-test assessment. Some of the studies included were Lester et al. (2014), Pareto, Haake, Lindström, Sjödén, and Gulz (2012) and Sung and Hwang (2013). In terms of the findings of that systematic review, included studies found students’ learning gains when students participate in collaborative learning activities with video games. Also, this kind of approach can be used in different subjects or to work different kinds of curricular knowledge, for instance, science, arithmetic, geography and the interest and understanding of other cultures.

In-service teachers’ attitudes towards the use of video games in the classroom

This paper focuses on teachers’ attitudes towards the use of video games in the classroom and more specifically focuses on pre-service teachers’ attitudes while studying in higher education.

According to Tejedor and García-Valcárcel (2006), previous studies have shown that teachers’ attitudes towards pedagogical innovations and Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in the classroom are one of the main factors influencing their adoption and integration. In terms of video games and their educational use, there is an increasing interest to know the teachers’ attitudes or perceptions towards them. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center and VeraQuest (2012) studied United States K-8th grade classroom teachers’ attitudes towards video games in the classroom, concluding that, in general, teachers have a very positive opinion of video games as an educational resource. Some of the benefits include increased collaboration among students, increased attention by the students to specific tasks, and benefits related to lower-performing students. Proctor and Marks (2013) focused on United States based exemplar primary and secondary teachers’ perceptions, use of and access to computer-based games and technology for classroom instruction, while Watson, Yang, and Ruggiero (2012) explored United States teachers’ perceptions of barriers to using video games for instruction. In that sense, Watson et al. (2012) found that four factors affect the use of video games in the classroom: challenges to implementing games effectively, challenges with using technology, the current educational system and challenges with obtaining games. Noraddin and Kian (2014) explored university teachers’ perceptions of using video games in educational practices at Malaysian universities and found that most Malaysian university teachers have a positive attitude towards using video games in their classroom. Additionally, video games associations and the video game industry, such as AEVI (The Spanish Association of Video Games) in Spain, are also interested in the use of video games in education and teachers’ attitudes about that. AEVI & GfK (2012) performed a study with 511 Spanish teachers, which included the question ‘Do you believe that video games can be an effective educational tool for students aged between 5 and 12 years old?’. Of the participants, 78.7% believed that video games can be an effective educational tool (33.3% of the participants choose the ‘surely yes’ option and 45.4% of the participants choose the ‘probably yes’ option).

Pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards the use of video games in the classroom

It is important to not only focus on in-service teachers’ attitudes, but also on pre-service teachers’ attitudes because these attitudes form the basis of their future educational practice when they begin working in the real context. Teachers’ attitudes are formed during their life, their home and social experiences, their experiences of the educational system and during their studies at the university, where they are being trained as teachers. In that sense, pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards video games as an educational resource can influence their training at university and can determine their attitudes towards this approach. Pastore and Falvo (2010) studied pre- and in-service teachers’ perceptions of video games in the K-12 classroom, using a survey that was completed by 98 participants (53 in-service teachers and 45 pre-service teachers). The findings indicated that both pre-service and in-service teachers perceive that using video games is an effective way to enhance learning, motivate students, and to incorporate visual representations into educational practices. Also, of the participants in their study, 60% of pre-service teachers and 55% of in-service teachers stated that they have or intend to use video games in their educational practices, and 71% of the pre-service teachers and 77% of the in-service teachers believed that implementing video games into educational practices is a valuable use of classroom time (Pastore & Falvo, 2010).

Bensiger (2011) conducted a survey with 75 pre-service teachers from different pre-service programmes (18 students from an early childhood programme, 14 from special education, 15 from middle school, 24 from secondary education and four from other programmes) at the University of Cincinnati. The findings showed that pre-service teachers have experience playing video games and consider that video games enhance learning, but they foresee barriers and obstacles to the use and implementation of video games in their learning environment. However, these teachers would be interested in integrating video games into their educational practices if they receive the opportunity. Additionally, in terms of gender, more female (70%) pre-service teachers believed that there are barriers and obstacles to using video games in the learning process than male pre-service teachers (30%) (Bensiger, 2011).

Jenny, Hushman, and Hushman (2013) explored 23 United States physical education pre-service teachers’ perceptions of motion-based video gaming in education to know their perceptions and to ascertain whether differences in their perceptions relate to the number of hours they play video games in their daily lives. The findings showed that the participants think that motion-based video gaming is fun and enjoyable and would increase student motivation and student physical activity, but do not always simulate the same concepts or motor movements of the actual sport. Regarding the number of hours, the students were categorised as either non-video game players (0 h), frequent video game players (1 to 4 h per day) or habitual video game players (over 5 h per day). Statistically significant differences were found in the students’ average perceptions based on the hours spent playing video games. Specifically, non-video game players and frequent video game players obtained a statistically lower mean perception of using motion-based video gaming in education than habitual video game players. No statistically significant difference existed between non-video game players and frequent players.

Ray, Powell, and Jacobsen (2014) explored the perceptions of 41 pre-service teachers (20 elementary and 21 secondary levels) regarding the use of video games as an educational resource and the level of willingness to implement video games into their educational practices. The results showed that the pre-service teachers perceived the value of video games as an educational tool, taking into account, for instance, for implementing student-centred teaching methodologies, contributing to achieve meaningful learning, promoting a positive attitude towards the learning process and supporting diverse learners. However, 80% of the participants stated that educators need training and to learn how to use video games (Ray et al., 2014).

Cózar-Gutiérrez and Sáez-López (2016) worked with 89 university students in the second year of their Master’s degree in primary education course at the University of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). They implemented an intervention to educate the students in the pedagogical integration of video games for teaching historical and artistic content, using MinecraftEdu, the educational version of the game Minecraft. Based on a quasi-experimental design with pre- and post-tests, the findings indicate that more than 95% of the students had positive perceptions of game-based learning and considered it essential to teachers’ initial training. Over 96% of participants also thought that game-based learning allows for active participation and student learning and more than 80% of the sample believed that this approach helps student’ engagement with the content. Furthermore, almost all of the students (over 97% of the sample) agreed that working on immersive environments facilitates collaborative advantage.

As can be seen, existing literature examines the different attitudes and perceptions of pre-service teachers from different educational levels towards using video games in education while incorporating different variables. Our work focuses on first year university pre-service primary teachers’ attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games.

Method

The main objective of our work is to investigate whether first year university pre-service primary teachers hold a generally positive or negative attitude towards collaborative learning with video games. Given that playing video games is a common form of entertainment for higher education students, we also aim to ascertain whether their attitude towards collaborative learning with video games is influenced by (1) the experience of playing video games (taking into account the number of years they have played video games), (2) the frequency of playing video games in their daily lives and (3) their gender.

The initial hypotheses of our work are the following ones:

-

The pre-service primary teachers hold a positive attitude towards collaborative learning with video games.

-

The pre-service primary teachers who have play video games for more years have more positive attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games.

-

The pre-service primary teachers who play more frequently have more positive attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games.

-

The male pre-service primary teachers have more positive attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games than female students.

Then, the variables to take into account are:

-

Criterion variable: the attitude towards collaborative learning with video games.

-

Predictor variables: the experience of playing video games (considering the number of years they have played video games), the frequency of playing video games in their daily lives and their gender.

To address the objectives of this work, we chose a quantitative approach, using a questionnaire with a 5-point Likert attitude scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with 33 items created ad hoc for this study (Appendix A). The design of the scale was based on the literature review about video games and teachers’ attitudes and on a previous study about the development of collaborative projects using ICT in schools (García-Valcárcel, 2015). The reliability of the scale is 0.929, based on Cronbach’s alpha coefficient; thus, the scale has high internal consistency. The questionnaire included demographic questions and other questions related to the students’ experience as players of video games such as the number of years students have played video games (‘Never’, ‘<2 years’, ‘2–8 years’, ‘9–15 years’ and ‘>15 years’) and the frequency of playing video games as entertainment (‘Never, ‘Occasionally: 1–3 days a month’, ‘Frequently: 1–3 days a week’ and ‘Every day’).

The questionnaire was administered to 193 students during the 2014–2015 academic year at the University of Salamanca. We administered the questionnaire during class time of the ‘Information and Communication Technologies in Education’ course from the first year of the Bachelor’s degree in Primary Education. We collected data from all three campuses of the University of Salamanca (Salamanca, Ávila and Zamora).

Results

We initiate the presentation of the results showing the characteristics of the sample. The total sample was 193 students and, of the students participating in the research, 65 students (33.7%) were men and 128 were women (66.3%). The students were 17–32 years old and the statistical mode was 18 years old (43% of the sample). In this way, both issues, the proportion of women and men and the age of the students, are in line with the student population of this degree.

Overall, the future primary school teachers show a positive attitude towards collaborative learning with video games. The students obtain a mean (\( \overline{x} \)) of 3.65 (out of 5), which is nearly the option “Agree” and it is above the midpoint of the scale. Furthermore, the coefficient of variation (CV) is low (0.13), which indicates a certain homogeneity in the scores. More measures of descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2.

Regarding the two variables about the use of video games, firstly, the majority of students (163; 85%) had played video games, and 30 students (15%) had never played video games. 56 (29%) of the students had been playing video games for between 2 and 8 years, being the most chosen option, followed by 27% of the students, who had been playing video games for less than 2 years, 19% of the students had been playing between 9 and 15 years, and 10% students for more than 15 years. Secondly, in terms of the frequency, 49% of students played ‘Occasionally (1–3 days a month)’, 18% of the students played frequently (1–3 days a week) and only 4% of the students played every day. Thirdly, in terms of gender, male students have more experience and play more frequently than female students (as we can see in Tables 3 and 4, Figs. 1 and 2).

In terms of the objectives related to students’ previous experience with video games and students’ use of video games and their relation to their attitudes, it is necessary to test firstly the normality of the distribution of the data to determine the use of parametric or nonparametric test. We tested the normality of the distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The results of 0.006 meant that we were unable to assume normality of the distribution and we thus needed to conduct inferential analysis with nonparametric test. In this way, we conducted inferential analysis to find whether any statistically significant differences existed among the variables.

Regarding the students’ experience as players of video games, we performed the Kruskal Wallis test for k samples of independent measures, with an α = .05 significance level, to find out whether the length of time they have been playing video games as entertainment affects their attitudes. The findings confirmed a statistically significant difference based on the number of years they have been playing video games (p = .013), thus indicating that students who have been playing more years have a more positive attitude towards using video games in collaborative learning. Table 5 and Fig. 3 show that the mean increases as the number of years spent playing video games increases.

To compare pairs of groups (that is to say, taking into account each option response as a group as Table 5 shows), we conducted a post-hoc comparison. The results show a statistically significant difference (α = .05 significance level) between groups A (never) and E (>15 years; p = .036) in the total sample, showing more positive attitude students who have played video games for more than 15 years.

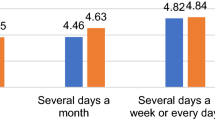

Regarding the frequency of play video games as entertainment, we also performed the Kruskal Wallis test for k samples of independent measures at an α = .05 significance level to analyse if the time that students dedicate to playing video games generate statistically significant differences among their attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games. Table 6 and Fig. 4 show that the frequency of playing video games generates a statistically significant difference among their attitudes, and the attitude becomes more positive as the students dedicate more time to playing video games.

Regarding the post-hoc comparisons between groups, a statistically significant difference (α = . 05 significance level) exists between groups A and C (p = .000), A and D (p = .029), and B and C (p = .030) in the total sample. These results show that statistically significant differences exist between the following:

-

students who never play video games and students who play frequently,

-

students who never play video games and students who play every day, and

-

students who play video games occasionally and those who play frequently.

Finally, in terms of differences by gender, we performed a Mann Whitney U test with a significance level of α = .05 to find out whether the gender affects their attitudes. As Table 7 shows, the results indicate a statistically significant difference between the groups (p = .042), showing more positive attitudes from the male students than from female students. Also, taking into account the gender and the variables related to experience and frequency of playing video games, Tables 3 and 4 show the results obtained.

Discussion

For the efficient integration of any new digital resource in educational practices, it is important to focus on issues such as the educational training related to these resources at initial training and in service training, teachers’ knowledge and teachers’ attitudes, school resources, head teacher’s endorsement and government support. In this study, we focused on pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards ‘collaborative learning with video games’. Pre-service teachers’ attitudes form the basis to in-service teachers’ attitudes and can affect the training they receive during their studies at university. In fact, if pre-service teachers have a negative attitude towards an ICT resource or a new methodology, they can refuse to use that resource or methodology and, even, can refuse to receive teacher training related to that topic.

This study found that the University of Salamanca’s first-year pre-service primary teachers showed a positive attitude towards collaborative learning with video games (mean = 3.65, that is nearly the option “Agree” in the scale and it is above the midpoint of the scale). These results are in line with other studies such as Bensiger (2011), Cózar-Gutiérrez and Sáez-López (2016), Jenny et al. (2013), Pastore and Falvo (2010) and Ray et al. (2014), thus showing that future teachers of different educational levels have a positive attitude towards using video games in education. The benefits of using video games in education include increasing students’ motivation, engagement and active participation; promoting a positive attitude towards the learning process; contributing to achieving meaningful learning; incorporating visual representations in the classroom; using student-centred teaching methodologies; and supporting diverse learners. Furthermore, in Cózar-Gutiérrez and Sáez-López (2016), other benefit highlighted is the collaborative advantages of working in immersive environments. Even, in terms of in-service teachers, K-8th grade teacher participants in The Joan Ganz Cooney Center and VeraQuest (2012) pointed to increased collaboration among students as a benefit of using video games as an educational resource.

It is commonly thought that young generations have more positive attitudes to the use of video games in education because their childhood is surrounded by video games. It is also thought that the next generations of teachers and teachers with more experience playing video games will have more positive attitudes to using video games in collaborative learning activities; our study supports this thought. Among two of the three variables analysed in our study—experience and frequency of playing video games—students who play video games for more years and who play more frequently have more positive attitudes to using video games in collaborative learning activities. These results align with those of Jenny et al. (2013) in which non-video game players and frequent video game players have lower mean perception of the use of motion-based video games in education than habitual video game players. Our findings show that the more years and time students have played video games, the better attitudes they present towards collaborative learning with video games. Also, in terms of the third variable, that is to say, the gender, our findings show that male students have more positive attitude towards collaborative learning with video games than female students.

These findings add to a growing body of literature on video games and education and teachers’ attitudes towards them. Highlighting how these findings add to the existing knowledge on the subject, firstly, the data is remarkable due to the size of our sample. We obtained a larger sample size (193 primary pre-service teachers) than the other studies cited previously on this work which used data from less than 100 pre-service teachers. It allows a deeper insight into the attitude of pre-service teachers to video games. Secondly, we focus on collaborative learning, one of the possible approaches when video games are used in education, which allows the work between peers and mixing the beneficial possibilities of video games and collaborative learning. Then, our study provides data about this specific approach. Instead, other works focus on teachers’ general opinion about the use of video games in education or on other specific topics, for instance, motion-based video games or serious games. Thirdly, we only focus on first year university pre-service primary teachers, taking into account that other studies mix data from pre-service teachers and, also, in-service teachers, from different levels. Our study allows a specific and thorough understanding about the attitudes of future teachers (before working in a classroom as a teacher), of a specific educational level (Primary Education) and at a specific moment on their studies (their first year at the University).

Conclusion and future work

This study explored pre-service primary teachers’ attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games to examine whether they have a positive attitude when they start their university studies, which can affect their training about this topic. The results obtained provide information about one of the main factors that influences the integration of video games in education. We obtained a large sample size (193 primary pre-service teachers), which includes almost all the students who were studying in the first year at this university during the 2014–2015 academic year. In conclusion, the male students and students who play video games for more years and who play more frequently have more positive attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games, and then the results confirm our hypotheses.

Our future work will study pre-service primary school teachers’ attitudes towards collaborative learning using a qualitative approach, e.g. interviews or focus groups, with higher education students. This approach could enrich the analysis of this topic, allowing a more thorough understanding. We will also continue working with university students and conduct longitudinal studies with the same sample of students through to the end of their degree. Furthermore, as the students have positive attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games, the authors are working on an educational proposal about collaborative learning with video games for pre-service primary teachers’ training purposes. The training will not only provide examples and theories of using video games in education, but will also implement the use of video games into the training sessions. As our study shows, previous experience can make a difference; thus, it is important to give future teachers the opportunity to test and play with different video games.

Future studies also need to focus on the attitudes of a specific level of pre-service teachers such as pre-service primary school teachers or pre-service secondary school teachers. The benefits and uses of video games in education can differ depending on the school level, and mixing the different levels can distort the analysis and comprehension of the results.

In any case, it is necessary to explore the attitudes of our future teachers and in-service teachers and examine the relation between their attitudes and real teaching practices. As the main characters in the educational process, the teachers and children need to be comfortable with new practices to achieve the final objective of educational system, which is the complete formation of the children.

Abbreviations

- ICT:

-

Information and Communication Technologies

- VGSCL:

-

Video Game-Supported Collaborative Learning

References

AEVI, & GfK. (2012). Estudio Videojuegos, educación y desarrollo infantil. Fase cuantitativa. http://www.aevi.org.es/web/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/10376-Informe-Adese-Fase-Cuantitativa-200120121.pptx. Accessed 21 Nov 2016.

AEVI. (2011). El videojugador español: perfil, hábitos e inquietudes de nuestros gamers. http://www.aevi.org.es/web/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/EstilodeVidayvaloresdelosjugadoresdevideojuegos_resumenpresentacion.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

AEVI. (2015). Anuario AEVI 2014. Anuario de la industria del videojuego. http://www.aevi.org.es/anuario2014/#p=1. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Annetta, L. A., Minogue, J., Holmes, S. Y., & Cheng, M. T. (2009). Investigating the impact of video games on high school students’ engagement and learning about genetics. Computers & Education, 53(1), 74–85. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.12.020.

Bakker, M., Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M., & Robitzsch, A. (2015). Effects of playing mathematics computer games on primary school students’ multiplicative reasoning ability. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 55–71. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.09.001.

Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2007). Técnicas de aprendizaje colaborativo: Manual para el profesorado universitario. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia y Ediciones Morata.

Baytak, A., & Land, S. M. (2010). A case study of educational game design by kids and for kids. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 5242–5246. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.853.

Bensiger, J. (2011). Perceptions of pre-service teachers of using video games as teaching tools (Doctoral Thesis, University of Cincinnati). https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/ucin1337363651/inline. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Braghirolli, L. F., Ribeiro, J. L. D., Weise, A. D., & Pizzolato, M. (2016). Benefits of educational games as an introductory activity in industrial engineering education. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 315–324. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.063.

Calzadilla, M. E. (2002). Aprendizaje colaborativo y Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación. OEI-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación. http://www.rieoei.org/deloslectores/322Calzadilla.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2017

Carbonaro, M., Szafron, D., Cutumisu, M., & Schaeffer, J. (2010). Computer-game construction: A gender-neutral attractor to computing science. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1098–1111. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.007.

Carrió, M. L. (2007). Ventajas del uso de la tecnología en el aprendizaje colaborativo. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 41. http://www.rieoei.org/deloslectores/1640Carrio.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2017.

Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., & Sáez-López, J. M. (2016). Game-based learning and gamification in initial teacher training in the social sciences: An experiment with MinecraftEdu. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(2). doi:10.1186/s41239-016-0003-4.

Denner, J., Werner, L., & Ortiz, E. (2012). Computer games created by middle school girls: Can they be used to measure understanding of computer science concepts? Computers & Education, 58(1), 240–249. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.006.

Dickey, M. D. (2011). World of Warcraft and the impact of game culture and play in an undergraduate game design course. Computers & Education, 56(1), 200–209. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.005.

Ebner, M., & Holzinger, A. (2007). Successful implementation of user-centered game based learning in higher education: An example from civil engineering. Computers & Education, 49(3), 873–890. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2005.11.026.

García-Valcárcel (Coord.) (2015). Proyectos de trabajo colaborativo con TIC. Madrid: Síntesis.

González, L., & Martín, M. (2016). Creación de videojuegos en la asignatura ‘TIC aplicadas a la Educación’ por. estudiantes del Grado de Maestro de Educación Infantil. In M. Meirinhos, A. García-Valcárcel, V. Gonçalves, L. González Rodero, M. R. Patrício, & J. S. Sousa (Eds.), Livro de atas da Conferència Ibérica em Inovação na. Educação com TIC (ieTIC 2016) (pp. 219–234).

Grupo F9. (2006). Age of Empires II: The Conquerors Expansion (I). Comunicación y Pedagogía, 211, 81–84.

Halpern, D. F., Millis, K., Graesser, A. C., Butler, H., Forsyth, C., & Cai, Z. (2012). Operation ARA: A computerized learning game that teaches critical thinking and scientific reasoning. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7(2), 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2012.03.006.

Hill, V. (2015). Digital citizenship through game design in Minecraft. New Library World, 116(7/8), 369–382. doi:10.1108/NLW-09-2014-0112.

Jenny, S. E., Hushman, G. F., & Hushman, C. J. (2013). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of motion-based video gaming in physical education. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 9(1), 96–111.

Lester, J. C., Spires, H. A., Nietfeld, J. L., Minogue, J., Mott, B. W., & Lobene, E. V. (2014). Designing game-based learning environments for elementary science education: A narrative-centered learning perspective. Information Sciences, 264, 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2013.09.005.

Lindo-Salado-Echeverría, C., Sanz-Angulo, P., De-Benito-Martín, J. J., & Galindo-Melero, J. (2015). Aprendizaje del Lean Manufacturing mediante Minecraft: aplicación a la herramienta 5S. RISTI - Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, 16, 60–75. doi:10.17013/risti.16.60-75.

Martín, M. (2015). Videojuegos y aprendizaje colaborativo. Experiencias en torno a la etapa de Educación Primaria. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 16(2), 69–89. doi:10.14201/eks20151626989.

Martín, M., Basilotta, V., & García-Valcárcel, A. (2016). An approach to Spanish primary school teachers’ attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games and the influence of teacher training. In F. J. García-Peñalvo (Ed.). Proceedings TEEM’16 Fourth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality. (pp. 715–719). New York: ACM.

Martín, M., & Martín, J. L. (2015). Propuesta didáctica en torno a Habilidades para la Vida y videojuegos: Los Sims 2. Comunicación Efectiva y aprendizaje colaborativo. Press Button, 1, 90–126. http://www.pressbutton.es/wp-content/.uploads/2015/05/3.-Marta-Mart%C3%ADn-de-Pozo-y-Jos%C3%A9-Luis-Mart%C3%ADn-.L%C3%B3pez.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Marín, V., Ramírez, A., & Cabero, J. (2010). Los videojuegos en el aula de Primaria. Propuesta de trabajo basada en competencias básicas. Comunicación y pedagogía, 244, 13–18. http://www.centrocp.com/comunicacionypedagogia/comunicacion-y-pedagogia-244.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Martín-Moreno, Q. (2004). Aprendizaje colaborativo y redes de conocimiento. In M. L. Delgado, M. Cuevas, A. M. Fuentes, C. Torres, J. A. Pareja, J. F. Romero, A. C. Mingorance, J. A. Fuentes, J. L. Villena, Y. A. Carretero & M. G. Fernández (Coords.) Actas de las IX Jornadas Andaluzas de Organización y Dirección de Instituciones Educativas. Granada, 15–17 de diciembre (pp.55–70). Granada: Grupo Editorial Universitario.

Mateos, R. N. (2014). El uso de videojuegos en el aula: análisis y propuesta (Master’s thesis, Universidad Pública de Navarra). http://academica-e.unavarra.es/handle/2454/11412. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Meyer, B., & Sørensen, B. H. (2009). Designing serious games for computer assisted language learning – a framework for development and analysis. In M. Kankaanranta & P. Neittaanmäki (Eds.), Design and use of serious games (Vol. 37, pp. 69–82). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Miller, M., & Hegelheimer, V. (2006). The SIMs meet ESL Incorporating authentic computer simulation games into the language classroom. Interactive Technology & Smart Education, 3(4), 311–328. doi:10.1108/17415650680000070.

Muñoz, R., Barcelos, T. S., Villarroel, R., Barría, M., Becerra, C., Noel, R., & Silveira, I. F. (2015). Uso de Scratch y Lego Mindstorms como apoyo a la docencia en Fundamentos de programación. In X. Canaleta, A. Climent, & L. Vicent (Eds.), Actas de las XXI Jornadas sobre la Enseñanza Universitaria de la Informática (pp. 248–254). Andorra La Vella: Universitat Oberta La Salle.

Newzoo. (2016). The global games market reaches $99.6 billion in 2016, mobile generating 37%. https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/global-games-market-reaches-99-6-billion-2016-mobile-generating-37/. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Noraddin, E. M., & Kian, N. T. (2014). Academics’ attitudes toward using digital games for learning & teaching in Malaysia. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 2(4). http://www.mojet.net/frontend/articles/pdf/v02i04/v02i04-01.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Núñez, E., Van Looy, J., Szmalec, A., & De Marez, L. (2014). Improving arithmetic skills through gameplay: Assessment of the effectiveness of an educational game in terms of cognitive and affective learning outcomes. Information Sciences, 264, 19–31. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2013.09.030.

Padilla, N., González, J. L., & Gutiérrez, F. L. (2009). Collaborative learning by means of video games: An entertainment system in the learning processes. In I. Aedo, N. S. Chen, Kinshuk, D. Sampson, & L. Zaitseva (Eds.), Proceedings The Ninth IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Riga (pp. 215–217). USA: IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICALT.2009.95.

Padilla, N., González, J. L., Gutiérrez, F. L., Cabrera, M. J., & Paderewski, P. (2009). Design of educational multiplayer videogames: A vision from collaborative learning. Advances in Engineering Software, 40(12), 1251–1260. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2009.01.023.

Papastergiou, M. (2009). Digital game-based learning in high school computer science education: Impact on educational effectiveness and student motivation. Computers & Education, 52(1), 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.004.

Pareto, L., Haake, M., Lindström, P., Sjödén, B., & Gulz, A. (2012). A teachable-agent based game affording collaboration and competition: evaluating math comprehension and motivation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(5), 723–751. doi:10.1007/s11423-012-9246-5.

Pastore, R. S., & Falvo, D. A. (2010). Video games in the classroom: Pre- and in-service teachers’ perceptions of games in the K-12 classroom. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 7(12), 49–57.

Proctor, M. D., & Marks, Y. (2013). A survey of exemplar teachers’ perceptions, use, and access of computer-based games and technology for classroom instruction. Computers & Education, 62, 171–180. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.022.

Ray, B. B., Powell, A., & Jacobsen, B. (2014). Exploring preservice teacher perspectives on video games as learning tools. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 31(1), 28–34. doi:10.1080/21532974.2015.979641.

Romero, M., Usart, M., Ott, M., Earp, J., de Freitas, S. & Arnab, S. (2012). Learning through playing for or against each other? Promoting collaborative learning in digital game based learning. In ECIS 2012 Proceedings. Paper 93. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2012/93. Accessed 18 Jan 2017.

Scagnoli, N. I. (2006). El aprendizaje colaborativo en cursos a distancia. Investigación y Ciencia, 36, 39–47.

Statista. (2016). Value of the global video games market from 2011 to 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars). https://www.statista.com/statistics/246888/value-of-the-global-video-game-market/. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Sun, C. T., Ye, S. H., & Wang, Y. J. (2015). Effects of commercial video games on cognitive elaboration of physical concepts. Computers & Education, 88, 169–181. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.05.002.

Sung, H. Y., & Hwang, G. J. (2013). A collaborative game-based learning approach to improving students’ learning performance in science courses. Computers & Education, 63, 43–51. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.019.

Tejedor, F. J., & García-Valcárcel, A. (2006). Competencias de los profesores para el uso de las TIC en la enseñanza. Análisis de sus conocimientos y actitudes. Revista española de pedagogía, 64(233), 21–43.

The Joan Ganz Cooney Center, & VeraQuest. (2012). Teacher attitudes about digital games in the classroom. http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/jgcc_vq_teacher_survey_2012.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Van Eck, R. (2006). Digital game-based learning: It’s not just the digital natives who are restless. EDUCAUSE Review, 41(2), 16–30.

Venegas, A. (2013). Competencias básicas, praxis educativa a través de Europa Universalis III. http://www.zehngames.com/investigacion/trabajando-las-competencias-basicas-con-europa-universalis-iii/. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Venegas, A. (2014). Recursos didácticos: Faraón y el Antiguo Egipto. http://www.zehngames.com/investigacion/recursos-didacticos-faraon-y-el-antiguo-egipto/. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Vernadakis, N., Papastergiou, M., Zetou, E., & Antoniou, P. (2015). The impact of an exergame-based intervention on children’s fundamental motor skills. Computers & Education, 83, 90–102. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.01.001.

Watson, W. R., Yang, S., & Ruggiero, D. (2012, November). Games in schools: teachers’ perceptions of barriers to game-based learning. Paper presented at the 2012 AECT International Convention, Louisville. http://www.aect.org/pdf/proceedings13/2013/13_32.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2016.

Yang, Y. T. C. (2015). Virtual CEOs: A blended approach to digital gaming for enhancing higher order thinking and academic achievement among vocational high school students. Computers & Education, 81, 281–295. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.004.

Yang, Y. T. C., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Empowering students through digital game authorship: Enhancing concentration, critical thinking, and academic achievement. Computers & Education, 68, 334–344. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.023.

Funding

In terms of the first author, this research was made possible through the funding of a FPU predoctoral grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport of Spain.

Also, regarding the second author, this research was made possible through the funding of a predoctoral grant from the Junta de Castilla y León, cofinanced by the European Social Fund.

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be shared because this data is from a doctoral dissertation that is currently being written.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to different parts of this research. The first author participated in the conception and design of the work, in data collection, data analysis and interpretation, in the creation of the article’s draft, the critical revision of the article and she approved the final version of the article to be submitted. The second author participated in data analysis and interpretation, the creation of the article’s draft, the critical revision of the article and she approved the final version of the article to be submitted. The third author helped with the conception of the work, and with data analysis and interpretation, participated in drafting the article and in the critical revision of the article, and, also, she approved the final version of the article to be submitted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Items of the “collaborative learning with video games scale”

-

1.

Implementing digital games for collaborative learning in the classroom is impossible.

-

2.

I would like to use digital games for collaborative learning activities in the classroom.

-

3.

If I used digital games for collaborative learning activities in the classroom, I would feel that I am wasting the class time.

-

4.

Using digital games for collaborative learning in the classroom allows for greater interaction between teachers and their students.

-

5.

I worry that using digital games for collaborative learning discourages students from exerting themselves in tasks and activities.

-

6.

Using digital games for collaborative activities allows students to collaboratively construct subject-based knowledge.

-

7.

I think receiving training about using digital games for collaborative learning is a waste of time

-

8.

I worry that using digital games for collaborative learning is a distraction from, and an impediment to, completing the course syllabus

-

9.

Using digital games for collaborative learning is a good strategy for the inclusion of students with special educational needs.

-

10.

Students who are working together when playing digital games pay more attention to the opinions of other students.

-

11.

I would use digital games for collaborative learning activities to encourage students to share task responsibilities.

-

12.

Students who play digital games collaboratively with their peers in the classroom have better relationships with each other

-

13.

I worry that using digital games for collaborative learning discourages students from taking learning seriously.

-

14.

Using digital games for collaborative learning enables students to learn to work autonomously.

-

15.

If my students asked to me to use digital games for collaborative learning activities in the classroom, I would refuse

-

16.

I would use digital games for collaborative learning activities to develop students’ life skills (for example, communication skills, mathematical competence, competences in science and technology, digital competence, learning to learn competence, social and civic competences, sense of initiative and entrepreneurship competences and cultural awareness and expression)

-

17.

Using digital games for collaborative activities/work helps students to explore ideas and concepts more fully.

-

18.

Students have greater autonomy in their learning when they participate in collaborative activities using digital games

-

19.

I think that using digital games for collaborative learning activities would increase students’ self-esteem

-

20.

Students would feel freer to share knowledge with other students if they used digital games for collaborative activities

-

21.

I believe that using digital games for collaborative activities increases students’ curiosity and motivation to learn more

-

22.

Digital games facilitate the implementation of collaborative activities with students.

-

23.

I believe that using digital games for collaborative activities increases student’s motivation and ability to “take the initiative”. .

-

24.

The discussions that occur between students working collaboratively within digital games and around digital games develop their conceptual understandings.

-

25.

I would like to work in a school which supports the use of digital games for collaborative learning activities with students.

-

26.

I would be overwhelmed if I had to use digital games for collaborative learning activities with students.

-

27.

I think that using digital games for collaborative activities develops students’ creativity

-

28.

The interactions between students working collaboratively within and around digital games increases the level of student learning

-

29.

I do not believe that using digital games for collaborative activities is an appropriate or effective classroom methodology

-

30.

I would never use digital games for facilitating collaborative learning activities.

-

31.

If there were sufficient resources within my school, I would definitely use digital games to facilitate collaborative learning activities in the classroom

-

32.

I believe that using digital games for collaborative activities in the classroom facilitates the development of student’s subject-based knowledge.

-

33.

I would like to collaborate with other teachers who are interested in using digital games for collaborative learning activities in the classroom.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Martín del Pozo, M., Basilotta Gómez-Pablos, V. & García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso, A. A quantitative approach to pre-service primary school teachers’ attitudes towards collaborative learning with video games: previous experience with video games can make the difference. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 14, 11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0050-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0050-5