Abstract

Background

The occurrence of Echinothrix calamaris Pallas, 1774 is reported for the first time in Colombia.

Results

Three specimens of Echinothrix calamaris were collected in two fringing reefs (La Azufrada and Playa Blanca) at Gorgona Island. The specimens now lie in the Echinoderm Collection of the Marine Biology Section at Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia).

Conclusions

This finding constitutes a range extension towards the Tropical Eastern Pacific, with only one previous record from Cocos Island. The list of Echinoids from the Pacific coast of Colombia now comprises 30 species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Richness or the number of species is, perhaps, the main attribute of biological diversity. There have been many efforts for the estimation of species richness, both for terrestrial and aquatic organisms and for plants and animals (Appeltans et al. 2012; Bouchet 2006; Foggo et al. 2003; Miloslavich et al. 2011; Mora et al. 2011). There are some groups of animals that are believed to have reached or are reaching their estimated number of species; however, most are far from having complete inventories (Bouchet 2006). New species to science and/or new geographic records of known species are reported often (e.g. Valencia-Giraldo et al., 2015). Echinoderms in general, and sea-urchins in particular, are included within the groups that are “not-well-known” (Bouchet 2006), and in regions where there is a paucity in studies and scarcity of experts, research efforts can easily lead to new records (e.g. Muñoz and Londoño-Cruz 2016) or the discovery of new species.

There are 79 sea-urchin species reported so far in Colombia (Benavides-Serrato et al. 2013; Muñoz and Londoño-Cruz 2016), of which 63.3% are found in the Caribbean and 36.7% in the Pacific. The family Diadematidae, a large and important family of sea-urchins, has only three representatives in the Pacific coast of Colombia [Astropyga pulvinata (Lamarck, 1816), Centrostephanus coronatus (Verrill, 1867) and Diadema mexicanum A. Agassiz, 1863]. Of these, A. pulvinata is rather rare, while C. coronatus and D. mexicanum are fairly common in coral reefs and less so in rocky reefs. The specimens of C. coronatus typically have white and black banded spines, a characteristic shared by other Diadematidae species (e.g. Echinothrix calamaris Pallas, 1774). The latter species, geographically restricted to the western Indian Ocean and Red Sea, has been reported only in one location in the entire Eastern Pacific: Cocos Island (Lessios et al. 1998), but recently we found some specimens of this species at Gorgona Island. Therefore, this paper adds a second locality for the Eastern Pacific and constitutes the first record of this species in Colombia.

Materials and methods

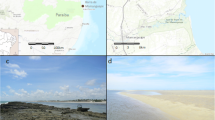

Three Echinothrix calamaris (EC) specimens were collected at Gorgona Island (3°00′55"N-78°14′30"W) on fringing coral reefs. One specimen (EC1) was found at La Azufrada reef (July 29, 2015) and two (EC2 and EC3) at Playa Blanca reef (April 19, 2016) at 2 and 3 m deep, respectively. The specimens were found unintentionally while conducting censuses of sea urchins. Once collected, the specimens were fixed in formalin (5%), and deposited in the Echinoderm Collection of Universidad del Valle (CRBMeq-UV), Cali, Colombia. These specimens are the first to be collected in the Colombian Pacific, and were identified using Coppard and Campbell (2006).

Results and discussion

Taxonomy

Order Diadematoida Duncan, 1889

Family Diadematidae Gray, 1855

Genus Echinothrix Peters, 1853

Species Echinothrix calamaris Pallas, 1774

We followed the identification key in Coppard and Campbell (2006) for the correct identification of the specimens, which showed the two distinctive arrangements and types of spines: Ambulacral (long, slender and hollow) and interambulacral (long, slender, and significantly larger and thicker than ambulacral spines) (Fig. 1). According to the ambulacral elevation and the form of the genital plates, our specimens match the brown color morph. In addition, an expert, Dr. Gordon Hendler, curator of echinoderms at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, confirmed our observations with photographs of the collected specimens taken when still alive.

Measurements and museum vouchers (within parenthesis) of collected specimen are as follows: EC1 – test diameter (t.d.) 40.41 mm, test height (t.h.) 19.58 mm (CRBMeq-UV: 2015–001); EC2 – t.d. = 31.88 mm, t.h. = 12.77 mm (CRBMeq-UV: 2016–001); and EC3 – t.d. = 25.64 mm, t.h. = 11.07 mm (CRBMeq-UV: 2016–001). These measurements are very small in comparison to the ones reported by Coppard and Campbell (2006). There are possibly two explanations for this difference: 1) our specimens were still juveniles, while the data reported by the previous authors might belong to adult specimens; or 2) we have observed that echinoids from Gorgona Island tend to have a consistent smaller size than reports elsewhere, e.g. Diadema mexicanum has a mean size of 19.62 mm, with a maximum size of 41.50 mm, while the mean size reported by Coppard and Campbell (2006) for this species is 75 mm with a maximum of 92 mm; or both.

In the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), Kroh (2013) reports the documented distribution of E. calamaris as encompassing the Maldives (Laamu Atoll, Malé), Red Sea (Sewul) and South Andaman Islands; other localities are also included (Fig. 2), but they are not confirmed. These localities are all located in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea regions. Only once has this species been reported from a locality outside the Indo-Pacific: Cocos Island, in the Tropical Eastern Pacific (TEP; Lessios et al. 1996, Alvarado and Cortés, 2009). These authors argue that the warm phase of El Niño Southern Oscillation could favor the dispersal and settlement of this species, and considering this recent discovery, we believe this could be a plausible explanation for its occurrence at Gorgona Island. However, considering the extent of the Pacific Ocean and the vast expanse of open ocean devoid of islands that might serve as stepping stones (Gilpin 1980) between the Central Pacific islands and the TEP (known as the East Pacific Barrier or Filter; Briggs 1961), it may be necessary to consider other means of dispersal (e.g. ballast water, rafting) besides larval transport by currents as the mechanisms that could explain the presence of E. calamaris in the TEP. Given that this is the first record of this species in the Colombian Pacific and that it is the second confirmed record in the TEP, it is possible that E. calamaris is successfully extending its distribution to the entire tropical Pacific Basin, although the specific mechanism of colonization is not yet fully understood. It will also be necessary to monitor this species at Gorgona Island and other localities to unambiguously confirm the establishment of viable populations in the Colombian Pacific.

World distribution of E. calamaris according to the information in Kroh (2013). Details of the distribution in the Pacific (a) and Indian (b) oceans are presented. The new record of this species at Gorgona Island coral reefs (TEP) is highlighted (c)

Conclusions

We report for the first time the presence of E. calamaris on coral reefs of Gorgona Island. On one hand, this increases the known species richness of Echinoids in the Pacific coast of Colombia (and South America), and on the other hand, it confirms the range extension of this species from Indian Ocean to the TEP.

Abbreviations

- CRBMeq-UV:

-

Colección de Referencia de Biología Marina Equinodermos de la Universidad del Valle (Echinoderms Marine Biology Reference Collection at Valle University)

- EC#:

-

Echiothrix calamaris (#: number of specimen collected)

- TEP:

-

Tropical Eastern Pacific

References

Alvarado JJ, Cortés J. Echinoderms. In: Whertmann IS, Cortés J, editors. Marine biodiversity of Costa Rica, Central América, springer science + Bussines media B.V. Netherlands; 2009. p. 421–33.

Appeltans W, Ahyong ST, Anderson G, Angel MV, Artous T, Bailly N, et al. The magnitude of global marine species diversity. Curr Biol. 2012;22(23):2189–202.

Benavides-Serrato M, Borrero-Pérez G, Cantera JR, Cohen-Rengifo M, Neira R. Echinoderms of Colombia. In: Alvarado JJ, Solís-Marín FA, editors. Echinoderms Research and Biodiversity in Latin América. Berlin: Springer-Velag Berlin Heidelberg; 2013. p. 145–82.

Bouchet P. The magnitude of marine biodiversity. In: Duarte CM, editor. The exploration of marine biodiversity scientific and technological challenges. Fundación BBVA; 2006. p. 31–64.

Briggs JC. The East Pacific barrier and the distribution of marine shore fishes. Evolution. 1961;15(4):545–54.

Coppard SE, Campbell AC. Taxonomic significance of test morphology in the echinoid genera Diadema gray, 1825 and Echinothrix Peters, 1853 (Echinodermata). Zoosystema. 2006;28(1):94–112.

Foggo A, Rundle SD, Bilton DT. The net result: evaluating species richness extrapolation techniques for littoral pond invertebrates. Freshw Biol. 2003;48:1756–64.

Gilpin ME. The role of stepping-stone islands. Theor Popul Biol. 1980;17:247–53.

Kroh, A. (2013) Echinothrix calamaris (Pallas, 1774). In: Kroh, A. & Mooi, R. (2017). World Echinoidea Database Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=213377. Accessed 3 Oct 2017.

Lessios HA, Kessing BD, Robertson DR. Massive gene flow across the World’s most potent marine biogeographic barrier. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1998;265:583–8.

Lessios HA, Kessing BD, Wellington GM, Graybeal A. Indo-Pacific echinoids in the tropical eastern Pacific. Coral Reefs. 1996;15:133–42.

Miloslavich P, Klein E, Díaz JM, Hernández CE, Bigatti G, et al. Marine biodiversity in the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of South America: knowledge and gaps. PLoS One. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014631.

Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S, Simpson AGB, Worm B. How many species are there on earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.

Muñoz CG, Londoño-Cruz E. First record of the irregular sea urchin Lovenia cordiformis (Echinodermata: Spatangoida: Loveniidae) in Colombia. Mar Biod Re. 2016;9:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0022-9.

Valencia-Giraldo D, Lazarus JF, Londoño-Cruz E. New records of decapod species from Malpelo Island, tropical eastern Pacific. Mar Biodivers. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-015-0401-1.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Hendler for confirmation of the species identification. We also thank Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones at Universidad del Valle for financing this project (C.I. 7970), and the Special Administrative Unit of the National Natural Parks System (UASPNN) and particularly the staff of Gorgona National Natural Park (Ximena Zorrilla and Luis Payan). Finally, we thank D. Valencia, L. Isaza and L. Gallego for field assistance in the collection of specimens, J. C. Mejía for preparing the distribution map (Fig. 2) and Dr. Philip A. Silverstone-Sopkin and F. Zapata for correction of the English manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant awarded to E. Londoño-Cruz by Universidad del Valle.

Availability of data and materials

All data gathered for this report, is available in the results and discussion session of this manuscript. Specimens are stored at the CRBMeq-UV as stated previously and might be available given all dispositions are met.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LO collected the first specimen, ELC collected specimens two and three, LO performed all measurements. ELC, LO and MZR participated equally in manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This species does not appear as evaluated in the IUCN Red List. We were granted a permit to collect sea urchin specimens at Gorgona National Natural Park by the Colombian Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development – (# PIDB DTPA No. 014–14). Additionally, Universidad del Valle, holds a broader permit (granted by the National Agency of Environmental Licences. Resolution number 1070, 28 August 2015 and National Natural Parks. Resolution number 120, 24 August 2015) that allow its faculty to collect specimens of wild species for non-commercial research.

Consent for publication

Does not apply.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Londoño-Cruz, E., Obonaga, L.D. & Zucconi-Ramírez, M. First record of Echinothrix calamaris (Echinoidea: Diadematidae) in the Colombian Pacific. Mar Biodivers Rec 11, 15 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-018-0150-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-018-0150-5