Abstract

Below-replacement fertility has persisted across European countries for a few decades, though, with variation. Delays in age at first union and first birth have been key factors in the declining fertility levels within these societies. While the vast majority of births occurs within a stable partnership, the link between partnership formation and childbearing is rarely taken into account. In this paper, we examine the role of partnership formation in explaining the gap between Sweden and Spain regarding transitions to first birth. We utilize data from the 2018 Spanish Fertility Survey and the 2012/2013 Swedish Generations and Gender Survey to explore transition probabilities to first birth and implement Kitagawa decomposition and standardization techniques. Results show that having a partner is a strong predictor of becoming a first-time parent in the next 3 years, mainly within the ages 25 to 35. On average, Swedish first-birth transition probabilities for women are only 12% higher than probabilities of Spanish counterparts within this age range, suggesting that the proportion of partnerships formed plays a crucial role in explaining the fertility gap. Decomposition results confirm that before age 30, 74% of the difference in first-order births among women are due to the difference in partnership composition. We further find that earlier union formation in Spain could potentially reduce childlessness levels. Overall, our study highlights the importance of examining the role of partnership dynamics in fertility studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As it is widespread and known, Swedish fertility is higher than that of the Spanish in the present-day. In both countries, however, the vast majority of children are born within the context of a stable partnership, which makes partnership and childbearing strongly connected. Cultural (Lesthaeghe, 2010; Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1988; Reher, 1998; Van de Kaa, 1987), economic (Alderotti et al., 2021; Matysiak et al., 2021; Vignoli et al., 2020), and gender-related (Esping-Andersen & Billari, 2015; Goldscheider et al., 2015; McDonald, 2000) reasons have been posited to contribute to cross-national differences in low fertility settings, and are generally assumed to have implications for higher-order childbearing. Moreover, the most influential theories on fertility and family behavior have all directly or indirectly addressed the issue of partnership formation. While most implicitly assume that partnership formation matters for the timing and quantum of childbearing, they often do not address cross-national fertility differences by partnership status, and few research has provided direct quantification of its importance for cohorts.

In this paper, we examine the extent to which partnership dynamics account for the fertility gap between Spain and Sweden—two high-income European societies with below-replacement level fertility, where the observed fertility often falls below the ideal family size (Sobotka & Beaujoaun, 2014). More specifically, the aim of our exploratory study is to explore the role of stable partnership formation in the transition to first birth within Spain and Sweden, taking a cohort approach and considering the role of age and intensity of partnership formation. We ask the following questions: How do first-birth transition probabilities vary between Sweden and Spain based on partnership status, gender, and age groups? To what extent can the gap in first-order TFRs between Sweden and Spain be explained by compositional differences (proportion in stable partnership partnership) or by rate changes (partnered first-order TFR)? Assuming fertility rates do not change, what would be the effect of postponing partnership formation on first-order TFR in Sweden and Spain? When referring to partnerships,Footnote 1 we refer to co-residence with a partner in the same household—combining marriage and cohabitation and use it as a proxy for economic independence from parents and engagement in a stable relationship. Furthermore, the focus is placed on the transition to first birth, as it is the parity transition for which (not) having a partner matters the most (Esteve et al., 2021). The impact of partnership dynamics on first birth also has consequences on higher-order fertility; not only does foregoing first births reduce the probability of having a second child, but it clearly impedes transition to higher parities. The answers to the research questions may have significant implications for theory development.

Given the biological limits of reproduction, the timing of partnership formation matters; therefore, we take a longitudinal perspective based on the experiences of Swedish and Spanish menFootnote 2 and women born between 1962 and 1979, highlighting the 1965–1969 cohort.Footnote 3 We follow their partnership histories and entrance into parenthood throughout their reproductive careers (between 18 and 40 years old) by utilizing retrospective information from survey data compiled in the Harmonized Histories dataset for Sweden and Spain (Perelli-Harris et al., 2011). Within the confines of our data, we take three complementary strategies for our two-country comparison. First, we calculate and compare the probabilities of transitioning to first birth based on partnership status at a given age. Second, we apply the Kitagawa decomposition method to examine the contribution of compositional differences in partnership status (partnered vs. non-partnered) to fertility rate differences based on partnership status. Third, we use standardization to investigate hypothetical first-birth outcomes based on earlier or later partnership formation (relative to the observed) for each country and gender. Before presenting the data and results, we provide some context for the comparison between Sweden and Spain.

Background

Below-replacement fertility is a universal trend across European and other high-income countries (Billari & Kohler, 2004; Kohler et al., 2002). However, significant cross-national differences exist. Southern European societies are characterized for having very low levels of fertility. Specifically, Italy and Spain were the pioneers of low fertility from the early-1990s (Kohler et al., 2002). Conversely, most Northern and Western European countries have had fertility levels wavering much closer to replacement level over time.

Variation in fertility across European countries are often correlated with differences in the timing and intensity of adulthood transition events, such as leaving the parental home, forming a stable partnership, getting married, and entering parenthood. Comparative research on the transitions to adulthood has extensively shown the diverging patterns across European societies (Billari, 2004; Billari & Liefbroer, 2010; Buchmann & Kriesi, 2011; Corijn & Klijzing, 2001). For example, the age at first birth has been on the rise across European countries since the 1970s (Neels et al., 2017). Among them, Southern European countries report the highest mean age (Eurostat, 2022a). The postponement of the transition to first child is strongly associated with other events such as leaving the parental home and, more importantly, forming unions (Baizán et al., 2003; Balbo et al., 2013; Billari & Liefbroer, 2010; Billari et al., 2007; Esteve et al., 2020). The majority of first births occur within marriages or consensual unions in Europe (Kiernan, 1999) and the lack of a stable partner has been reported as one of the reasons for unrealized fertility desires in Europe (Esteve et al., 2021; Testa, 2007). Despite the importance of partnership formation as proximate determinant of fertility, we lack studies that quantify its contribution in comparative perspective (Esteve et al., 2020).

Sweden and Spain: providing context for the comparison

Different fertility trends but both below-replacement level

While Scandinavian countries, the UK, and France are often categorized as having highest-low fertility in Europe, Southern European countries are categorized as the paradigm examples of having ‘lowest-low fertility’ (Billari & Kohler, 2004; Kohler et al., 2002). While Spain has experienced three decades of below-replacement level fertility (below a TFR of 2.1), Sweden’s TFR has been quite stable prior to the unexpected decline from 2010 (a TFR fluctuation of around 2.0 before 2010 and currently, around 1.7) (Eurostat, 2022a). Rates of childlessness differ between the two countries as well. On one hand, Spain continues to have one of the highest average ages at first childbearing in Europe and one of the highest rates of childlessness among women (Esteve et al., 2016)—around 20% of women born in the late 1960s (Reher & Requena, 2019; Sobotka, 2017). On the other hand, the proportion of childless Swedish women is around 14% (Sobotka, 2017).

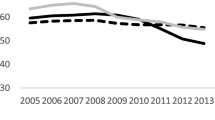

Relatedly, the completed fertility rates of more recent Spanish birth cohorts are relatively lower than the observed rates in Sweden and other Scandinavian countries. To illustrate this, Fig. 1 shows the cohort fertility rates (CFR) of women born between 1900 and 1979 highlighting Spain and Sweden. The Swedish CFR for women was relatively high and stable, around 2.0 children per woman. In contrast, Spain experienced a continuous decline in CFR since the late-1930s birth cohort—from above 2.5 children per woman to 1.3 children per woman by the 1978 cohort. This rapid decline in fertility, however, appears to have stalled at around a 1.2 CFR among the late-1970s cohort in Spain.

Cohort fertility by age 40 of women in Spain, Sweden and selected countries. Source: Calculated by authors based on Human Fertility Database (2021). CFR for Spanish women end with the 1978 cohort, respectively, while CFR for Swedish women end with the 1979 cohort

Different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds

When the second demographic transition (SDT) theory was formulated in the 1980s, Spain resembled a traditional, conservative country relative to its Nordic counterparts (Baizán et al., 2003; Kohler et al., 2002). In Spain, marriage was the main pathway to stable partnerships (Castro-Martín, 1993; García Pereiro et al., 2014), with the majority of marriages being a religious marriage (Muñoz & Recaño, 2011). Moreover, cohabitation and non-marital childbearing were still considered marginal phenomena (Domínguez-Folgueras & Castro-Martín, 2013), and divorce rates were still very low across the country (Bernardi & Martínez-Pastor, 2011; Castro-Martín, 1993; Miret-Gamundi, 1997). Initially, Spain became a paradox of the SDT because it combined low levels of fertility and postponement of first partnership formation with a small share of cohabitation and non-marital childbearing (Coleman, 2004; Dalla Zuanna & Micheli, 2004). Only in recent decades has Spain undergone rapid political, economic, and cultural changes that have influenced family formation patterns (Martín-García, 2013). During this period, earlier trends were replaced by new behaviors, such as the increasing postponement of first union and childbearing, increasing levels of union dissolution (Bernardi & Martinez-Pastor, 2011; Castro-Martín, 1992; Coppola & Di Cesare, 2008), and increasing levels of cohabitation and non-marital childbearing (Domínguez-Folgueras & Castro-Martín, 2013). Non-marital fertility also rose rapidly from 11% in 1995 to 36% in 2010 (Domínguez-Folgueras & Castro-Martín, 2013). Most recent estimates from 2020 show that more than half of live births now occur within marriages (Eurostat, 2022a).

Sweden, on the other hand, has had individualism and egalitarianism embedded into its society and welfare state. The country has also been internationally known for their generous family policies supporting women maintain a work–life balance (Andersson, 2020; Thomson et al., 2014), as well as their policies assisting young adults gain independence from their parental homes (Billari, 2004). It has been argued that this government assistance has helped facilitate childbearing among Nordic societies prior to the fertility decline in 2010 (Andersson, 2020). Sweden, in particular, has had one of the highest shares of premarital cohabitation and the highest share of births within cohabitation (Holland, 2013; Ohlsson-Wijk, 2011). In 2020, more than half of live births in Sweden occurred within non-marital couples (Eurostat, 2022a). Additionally, co-residence with a stable partner has long been diffused across socio-economic groups in Sweden, and cohabitation is a family form that has been indistinguishable from marriage—legally and societally (Hiekel et al., 2014; Hoem & Hoem, 1988; Ohlsson-Wijk et al., 2020). Therefore, it is no surprise that the majority of all first births in Sweden occur to unmarried, cohabiting couples (Holland, 2013; Ohlsson-Wijk, 2011).

Different age patterns in adulthood transitions

Spain is known for its ‘latest-late’ transition to adulthood (Billari, 2004), whereas Sweden is not.

In our study, we consider two specific adulthood transition events: entering a stable partnership and experiencing a first childbirth.

Entering a stable partnership

In Sweden, approximately 97% of women born between 1965 and 1969 have ever been in stable partnership by age 45.Footnote 4 Meanwhile, only 80% of Spanish have ever been in a stable partnership by age 45. Men appear to experience the event less frequently than women in both countries, although, there are more Swedish women and men who have ever been in a stable partnership at all ages, relative to their Spanish counterparts. Around 88% of Swedish men have ever been in a stable partnership by age 45, On the other hand, 81% of Spanish men have ever been in a stable partnership by age 45.

For the Swedish, the median age of first stable partnership formation is 21 for women and 23 for men. On the other hand, the median age is relatively higher for their Spanish counterparts (women: 27 and men: 29). The late transition to partnership formation among the Spanish is closely associated with the late timing of leaving the parental home (Baizán et al., 2003). In 2020, the average age for women to leave their parental home in Spain was around 29, while for Spanish men, it was 31 (Eurostat, 2022b). On the contrary, leaving the parental home occurs much earlier in Sweden where the average age for women and men was 18 in 2020.

Experiencing a first childbirth

88 and 80% of Swedish women and men are ever-parents by the age of 45, respectively. The median age of first childbirth is 27 for women and 30 for men. Among the Spanish, 74 and 65% of women and men have a child by age 45, respectively. The median age of first childbirth is 32 for women and 36 for men. Traditionally, leaving the parental home would coincide with marriage and family formation in Spain (Baizán et al., 2003), and this is, indeed, what we observe in Fig. 2.

Existing theories explaining the Sweden–Spain fertility gap

This section briefly describes where Spain and Sweden stand according to prominent theories attempting to explain differences in cross-national fertility. For instance, Spain is less advanced in the stages of the Second Demographic Transition (Lesthaeghe, 2010) and Gender Revolution (Esping-Andersen & Billari, 2015; Goldscheider et al., 2015) compared to Sweden—a paradigm example of being the most advanced in both theories. Only in recent decades has divorce become legalized in Spain (Bernardi & Martinez-Pastor, 2011), cohabitation recognized as a non-marginal pathway to family formation (Domínguez-Folgueras & Castro-Martín, 2013), and while Sweden is one of the most gender egalitarian societies (OECD, 2016), Spain is not. Divorce has also existed in Sweden for over a century, and cohabitation is the norm prior to marriage—as well as its equal alternative (Holland, 2013). The differences in the normalization of these processes within societies are most likely related to the prevalence and timing of stable partnership formation, which we argue here are important features for entering parenthood.

Different welfare regimes have also been linked to differences in fertility behaviors (Blossfeld et al., 2005; Esping-Andersen, 1999; Neyer, 2013). The de-familialized regimes of the Nordic societies, where responsibilities of care and the welfare of households lie on the welfare state and not on the family, observe higher fertility. On the contrary, Mediterranean societies with familistic regimes, where financial and caring responsibilities fall on the family, observe lowest-low levels of fertility. Reher (1998) suggests that the historical North–South differences in (intergenerational) family ties influence current differences in fertility levels. Specifically, southern countries have strong family ties, or strong intergenerational relationships, and northern countries have weak ties, characterized by weak intergenerational relationships. The environment of the former may have made it easier for the normalization of delayed transition to adulthood, such as leaving the parental home. This, in turn, also influences the postponement of childbearing and lower fertility. Differences in welfare regimes may also influence the consequences of economic uncertainty on societies (Blossfeld et al., 2005). Young adults in Spain, for instance, experienced more negative economic consequences due to the 2008/2009 financial crisis relative to Sweden (Puig-Barrachina et al., 2020). The rise in both subjective and objective economic uncertainty has also been found to deter childbearing, perhaps more so in Southern European contexts (Vignoli et al., 2016, 2020).

Such existing theories emphasize different aspects and confront the challenge of explaining why fertility is declining and why there are relatively large differences across European societies. It is uncommon to find studies focusing on how differences in partnership dynamics can explain fertility differences, as none of these theories explicitly question the importance of partnership dynamics.

Data

We use data from the Harmonized Histories dataset which has, to date, compiled and standardized 27 surveys from 23 various countries, the majority European (Perelli-Harris et al., 2011). In particular, we use the 2012/2013 Swedish Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) and the 2018 Spanish Fertility Survey (SFS) within this larger dataset. The retrospective nature of these surveys allows us to reconstruct respondents’ stable partnership and childbearing histories as person-months. We exclude individuals with incomplete partnership histories from our final sample. For Sweden, we exclude 17 women and 17 men; for Spain, we exclude 158 women and 182 men.

The GGS is an international compilation of fertility surveys containing rich micro-level information on life-courses and family dynamics (Gauthier et al., 2018; Vergauwen et al., 2015). The 2012/2013 Swedish GGS interviewed women and men born between 1933 and 1994, ages 18 to 79; the sample is representative, and the respondents are based on random samples taken from the Swedish population registers. The original sample contains 9688 individuals—4991 women and 4697 men. We end up with 1372 and 1280 women and men, respectively, after restricting the sample to native-born individuals born between 1962 and 1979. Birth cohorts are grouped by 5 years and are chosen based on the overlap between the two surveys, with foremost consideration towards following respondents through their reproductive career for as long as possible. The distribution of cases by birth cohort can be found in the Additional file 1: Table A1. Finally, we end up with 1355 Swedish women and 1263 men.

The 2018 SFS interviewed women and men born between 1962 and 2000, ages 18 to 55. It is a representative, cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Statistics Institute of Spain and is a continuation of the fertility surveys conducted in 1977, 1985, and 1999. The original sample consists of 17,175 individuals—14,556 women and 2619 men.Footnote 5 Restricting the Spanish sample as we did with the Swedish sample, we end up with 7571 Spanish women and 1301 men. This study defines being in a stable partnership as co-residing with an intimate partner and only considers biological childbearing. Furthermore, partnership status is a time-varying variable in our analysis, where dates are measured in months. Missing monthsFootnote 6 of an event occurrence are randomly imputed when the corresponding year is available. The main results will be presented based on the 1965–1969 birth cohort. This cohort is selected since it is the most complete in terms of observable partnership formation and first births until age 40. With the earlier cohort, only 2 years are covered (1962–1964), and with younger cohorts, first births at late ages are lost.

Methods

We employ the three techniques used to examine the influence of partnership dynamics on fertility, namely, transition probabilities to first birth, Kitagawa decomposition, and standardization. All of which are used to illustrate the Swedish–Spanish first-order TFR differences from distinct but inter-related dimensions. With the transition probabilities we focus on behavior across the reproductive period; specifically, we aim to explore whether fertility schedule differences exist after controlling for partnership status. Controlling for partnership status allows us to compare the first-birth probabilities between Swedish and Spanish individuals of the same age and with the same partnership status. For example, will the probability of entering parenthood within the next 3 years be similar between a 25-year-old Swedish and Spanish woman, both with a stable partner? The decomposition analysis, on the other hand, allows us to explore how much of the gap in first-order TFRs between Sweden and Spain is attributable to age-specific (1) differences in fertility behavior (e.g., the partnered first-order TFRs) or (2) differences in composition (e.g., the proportion of those in a stable partnership). In the decomposition, the former is referred to as the rate effect, and the latter, the composition effect. Lastly, standardization allows us to experiment with the influence of partnership composition on the first-order age-specific fertility rates in Spain and Sweden—keeping the observed partnership-specific first-order TFR constant in each respective country. We examine hypothetical age-specific first-order TFRs by pre-/postponing the observed stable partnership formation by 1–3 years. Below, we empirically illustrate these three techniques.

First-birth probabilities to examine transition to first birth in the next 3 years based on partnership status

Using retrospective data, we construct individual partnership and childbearing histories for native-born, childless women in each country and calculate first-birth probabilities as follows:

where \(x\), \(t\), and \(p\) indicate age, cohort, and partnership status, respectively. \(p=1\) indicates women who have a stable partner, while \(p=0\) indicates the opposite. \(b=1\) indicates women who have a first birth within the next 3 years. \(N(x,t,p)\) represents native-born, childless women, given age, cohort, and partnership status. It should be noted that observations 3 years before the survey year of each respective country have been censored in order to calculate the first-birth probabilities using only known information. This means that we censor all observations after 2009 for the Swedish sample, as the majority of interviews took place in 2012, and 2015 for the Spanish.

Kitagawa decomposition to distinguish rate and composition effects on first-order TFR differentials

Since the probabilities do not consider the proportion of (un-)partnered individuals at a given age, we are unable to distinguish to what extent the first-order TFR and the composition of (un-)partnered women and men contribute to differences in the transition to first birth between Sweden and Spain. To quantify this, we use the Kitagawa decomposition approach. We compute the first-order TFR based on partnership status, which is expressed as:

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) represent the minimum and maximum reproductive ages. \(\mathrm{ASFR}(x,t,p)\) and \(C(x,t,p)\) are the age-specific fertility rate and the proportion of women, respectively, given age, cohort, and partnership status. We follow the Kitagawa (1955) approach and decompose the difference in first-order TFR as the following:

where \(\Delta\) and overbar mean the difference and average between two populations, separately. For example, \(\Delta \mathrm{ASFR}\left(x,t,p\right)=\mathrm{ASFR}\left(x,t,p,\mathrm{ SWE}\right)-\mathrm{ASFR}\left(x,t,p,\mathrm{ ESP}\right)\), and \(\overline{C }\left(x,t,p\right)=\frac{C\left(x,t,p,\mathrm{ SWE}\right)+C\left(x,t,p,\mathrm{ ESP}\right)}{2}\). Based on Eq. (3), the two effects can be defined as:

Then, the \(\mathrm{total \, effect }=\mathrm{ rate \, effect }+\mathrm{ composition \, effect}\). While the rate effect summarizes the effect of age- and partnership-specific first birth rates on the first-order fertility differentials, the composition effect summarizes the effect of age-specific partnership composition on the differentials. It should be mentioned that the rate and composition effects can be further separated by partnership, as Eqs. (4) and (5) show (for an example, see Additional file 1: Fig. A6).

Standardization to observe how earlier/later partnership formation may impact first-order TFR

For the standardization, we employ Eq. (2) to calculate hypothetical first-order TFRs. We have two distinct scenarios, namely, earlier and later stable partnership formation. We assume that the hypothetical proportion of stable partnerships at age \(x\) will reach the actual stable partnership proportion at age \(x+n\) (or \(x-n\)), \(n\) representing the moving year(s). In other words, we move the \(C(x,t,p=1,\mathrm{ ESP})\) curve to the left (or right, correspondingly) \(n\) years (see Additional file 1: Fig. A2). Note that the hypothetical stable partnership proportion will remain the same as the observed proportion at the last age, and in the case of further postponement, we move the \(C(x,t,p=1,\mathrm{ ESP})\) curve to the right. At the first age, we consider that the declining speed is 0.02 per year. If the proportion is lower than 0, we force it to 0. Furthermore, we assume the \(\mathrm{ASFR}\left(x,t,p,\mathrm{ ESP}\right)\) remains constant for both scenarios. Since the non-stable partnership proportion will change correspondingly, \(1-C(x,t,p=1)\), and \(\mathrm{ASFR}(x,t,p=0)\) is negligible, this (direct) standardization can be employed to investigate the influence of stable partnership on first-order TFRs.

Results

In this section, we show the results for the 1965–1969 birth cohort. Full results are presented in the Additional file 1 (Figs. A1, A3, A4, and A5).

Transition to first birth among childless women and men by partnership status at a given age

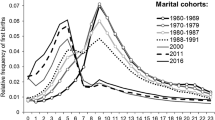

Figure 3 shows the probability of experiencing a first birth within the next 3 years at a given age for Swedish and Spanish women and men based on stable partnership status among those born between 1965 and 1969.Footnote 7,Footnote 8

Overall, we observe that having a stable partner drastically increases one’s probability of entering parenthood within the next 3 years at practically all given ages for women (Fig. 3). This is relative to not having a stable partner at that age. Although Swedish women with stable partners have higher probabilities for first childbirth compared to their Spanish counterparts, the probability of having a first child within the next 3 years among partnered women are the highest and most concentrated within the age range 25 to 35 for both countries. The average difference in transition probabilities among partnered women between these ages is approximately 12%, with Swedish women having a higher probability than the Spanish. While the transition probability to first birth within the next 3 years is highest at age 27 for Swedish women (0.52) and at age 29 for Spanish women (0.42), this concentration of ages may infer to the timing deemed ‘societally acceptable’ for childbearing among women born between 1965 and 1969 in Sweden and Spain. Furthermore, it may indicate that having a stable partner earlier than age 25 or later than age 35 is less impactful in the transition to first birth.

The general results for men are similar to that of women as seen in Fig. 3. For one, having a stable partner for men also shows a higher probability of experiencing a first birth within the next 3 years at a given age when compared to not having a partner.Footnote 9 The probabilities of entering fatherhood are lower for Spanish men than the Swedish at almost all ages—the exception being at age 27. First-birth probabilities for Spanish men with a stable partner are highest between the ages 25 and 35, similar to women. Contrastingly, first-birth probabilities for Swedish men are highest in the latter half of this timeframe, specifically, in their early 30 s. Transition probabilities among partnered men between the ages 25 and 35 is approximately 5% on average, with Swedish men having a higher probability than the Spanish. The concentration of higher transition probabilities, once again, may indicate the timing in which stable partnership is most impactful in the transition to first birth.

Decomposing differences in first births between Spain and Sweden

Swedish women have a higher first-order TFR compared to Spanish women at age 40, approximately 0.88 and 0.71,Footnote 10 respectively. Figure 4 presents the results of our Kitagawa decomposition, decomposing the first-order TFR differential of 0.17 between Swedish and Spanish women.Footnote 11 Overall, the primary contributor to the first-order TFR differential between Sweden and Spain for women is the composition effect with 0.21. The total rate effect is trivial (0.04) and only slightly offsets the positive composition effect. More specifically, our decomposition results show that the difference in first-order TFR is negligible at the young ages between 18 and 19. For women, the total effect at these ages is only slightly in favor of a higher Spanish fertility contributed by the rate effect. The composition effect, meanwhile, plays a positively significant role between the ages of 20 and 29, suggesting that more Swedish women are in stable partnerships than their Spanish counterparts. Before age 30, the compositional effect accounts for 74% of the differences between Sweden and Spain in first-order births. After age 30, however, Spanish women have a higher fertility than the Swedish. This is primarily driven by the rate effects.

Contribution of first-order rate and partnership composition to the first-order TFR differential by age group, 1965–1969. Source: Calculated by authors based on the Spanish Fertility Survey (2018) and Swedish Generations and Gender Survey (2013) from the Harmonized Histories dataset. ΔTFR = TFRSWEDEN − TFRSPAIN

We perform the same analysis for men. The total difference in first-order TFR between Swedish and Spanish men is 0.18, with a 0.76 Swedish first-order TFR and a 0.58 Spanish first-order TFR. The contributions of the rate and compositional effects toward this difference are illustrated again in Fig. 4. The composition effect is also the principal contributor for fertility differentials between Swedish and Spanish men (difference of 0.17), while again, the rate effect contributes minimally (0.02). At the youngest ages, 18 to 19, there are no differences in first-order TFR between Swedish and Spanish men. Swedish men experience more fertility at all age groups except between ages 30 to 34 and at age 40. From the ages 20 to 29, the partnership composition of Swedish men is the dominant contributor to the higher Swedish fertility—the composition effect being the largest between the ages 25 and 29. Before age 30, 75% of the first-order TFR difference between Swedish and Spanish men can be explained by compositional difference in partnerships. Meanwhile, the rate effect drives the fertility among men after age 30. Specifically, the rate effect explains the higher fertility of Spanish men relative to their Swedish counterparts. Between the ages 35 to 39, however, Swedish men appear to experience more first births. This differs from the situation of women, where Spanish women have higher fertility than the Swedish after age 30.

What if Spanish women form stable partners earlier or later than what is observed?

To further explore how the timing of first stable partnership formation impacts first-order TFR rates by age 40, we calculate hypothetical first-order TFRs for native-born Swedish and Spanish women and men as if they formed a stable partnership 1–3 years earlier.

In Fig. 5, we observe a marginal increase in first-order TFRs each year partnership formation hypothetically occurs earlier than the observed. The largest increase is if Spanish women formed stable partnerships one year earlier than the observed. The hypothetical first-order TFR improves from 0.71 to 0.76. If stable partnerships would form 3 years earlier than the observed, the Spanish first-order TFR would nearly match the observed Swedish rate by age 40—0.87 and 0.88 first-order TFRs, respectively. Although the Swedish first-order TFR is higher than that of the Spanish before age 35, they converge by age 40. This is because most Swedish women have already entered parenthood prior to age 35, while most Spanish women only begin entering parenthood during their 30 s. Figure 5 also shows hypothetical consequences of further delaying stable partnership formation 1–3 years later. The low scenario, a 1-year delay, can result in a 0.05 decrease in Spanish first-order TFR by age 40 for a first-order TFR of 0.66. The middle, a 2-year delay, and high, a 3-year delay, scenarios show a potential decrease of 0.11 and 0.16 children per woman—a first-order TFR of 0.60 and 0.55, respectively.

For Sweden, where the observed first-order TFR is 0.88, earlier stable partnership formation by 3 years suggests a hypothetical first-order TFR of 0.99. On the other hand, a postponement of 3 years suggests that the first-order TFR of Swedish women would be very similar to the Spanish—both approximately 0.71. Again, since Swedish family transitions occur earlier than their Spanish counterparts, there is a convergence of first-order TFR at later ages when Spanish women ‘catch-up’ due to their delayed childbearing.

Despite less men becoming parents in general relative to women, Fig. 5 further suggests Spanish men have a much lower transition to first birth than Swedish men—first-order TFR of 0.58 and 0.76, respectively. A delay of 3 more years from the actual situation could result in a first-order TFR of 0.44 for Spanish men. Similar to the convergence observed among women, the hypothetical Spanish first-order TFR for men converges with that of the observed Swedish rate at later ages. For Swedish men, postponing stable partnership formation impacts first-birth fertility levels to a greater extent compared to earlier partnership formation. This is due to partnership composition being the primary contributor to Sweden’s high fertility instead of the rate. In other words, the rate is unable to compensate for the negative impact of delaying partnership formation on the transition to first birth. Only marginal increases are observed in the hypothetical first-order TFRs with each year Swedish men form partnerships earlier. The already high contribution of partnership composition and the fixed fertility rate of entering fatherhood may explain this finding.

Discussion and conclusions

The relationship between partnership dynamics and childbearing in below-replacement fertility contexts is important to address in contemporary fertility research as the landscape of family formation continues to evolve across European societies. For example, singlehood and childlessness has been on the rise, and the Nordic countries have experienced an unexpected decline in period fertility (Esteve et al., 2016; Hellstrand et al., 2021; Reher & Requena, 2019; Sobotka, 2017). The findings of this study illustrate the importance of partnership formation with regard to entering parenthood. Furthermore, they indicate the necessity for more research on the determinants of partnership dynamics—especially, as it is likely related to transitions to adulthood and the difficulties young adults face to make these transitions.

Contextually, we compare the partnership formation and childbearing behaviors of Sweden and Spain. The inclusion of men in the study, which remains under researched in existing fertility literature, also provides a gender perspective. Sweden and Spain not only have different cultural, economic, and political histories, but they have distinct patterns in the timing of adulthood transition event occurrences (earliest-early vs. latest-late, respectively) (Billari, 2004) and have different levels of below-replacement fertility (highest-low vs. lowest-low, respectively) (Billari & Kohler, 2004; Kohler et al., 2002).

Several conclusions can be drawn from our analysis. First, having a stable partner could be a crucial element for childbearing regardless of country or gender. The immense majority of children are born within the context of a stable partnership, and having a stable partner could increase the probability of entering parenthood within the next 3 years. We find having a stable partner matters most from the ages 25 to 35 in entering parenthood, while first-birth transition probabilities are lower among those that have a stable partnership at older ages. Furthermore, first childbirth is particularly relevant to address when analyzing childbearing in below-replacement fertility societies as it not only allows for higher-order births, but recent studies exploring the parity-specific effects on fertility have found the decline in first-order births to be a significant contributor to the below-replacement-fertility trend in certain European countries (specifically, Southern European, German-speaking, and recently, Nordic countries) (Brzozowska et al., 2022; Hellstrand et al., 2021; Zeman et al., 2018).

Second, we find that partnership composition could explain more of the gap in first-order TFRs between Sweden and Spain, relative to childbearing behaviors based on partnership status. Between the ages 25 to 35, around 75% of the first-order TFR gap may be contributable to differences in partnership composition. While both Swedish women and men had higher first-order TFRs relative to their Spanish counterparts, our results illustrate a gender difference in the dominant contributing effect of the first-order TFR gap (i.e., the rate or composition effect) by age group. There is a higher proportion of young women forming stable partnerships in Sweden than in Spain, and we find that this is the most significant contributor to the first-order TFR differential between these two countries. At later ages, the childbearing of partnered Spanish women may also explain the first-order TFR differential between Sweden and Spain, however, much less so than the differences in partnership composition. The findings are similar for men, where the higher proportion of stable partnership composition among young Swedish men could explain more of the first-order TFR gap between Sweden and Spain relative to the differences in partnered childbearing.

Third, the timing of first stable partnership formation may be imperative for improving the first-order TFR, particularly so for native Spanish women and men. Both the decomposition and standardization analysis suggest this. If Spanish women entered stable partnerships 3 years earlier than what is observed (specifically for the 1965–1969 birth cohort), however, the first-order TFR would become similar to the Swedish by age 40. This suggests that earlier stable partnership formation in Spain could contribute to higher first-order TFRs, even if their childbearing timing and intensity persists at the observed level. Forming a stable partnership 3 years earlier for Spanish women and, most likely, more than 3 years for men, results in first-order TFRs which are comparable to their Swedish counterparts. Results from our standardization exercise show Spanish men should enter a stable partnership several years earlier than Spanish women to potentially achieve a first-order TFR comparable to their respective Swedish counterparts. A likely explanation for this is that men do not have the same biological limitations of childbearing as women do; therefore, not only do men generally have their first child later than women, but the first-order TFRs for men are also more spread out over and less concentrated within a certain age range.

In general, we find that the Swedish form more stable partnerships and at earlier ages, and the Spanish form less stable partnerships and at later ages. We also find fewer Spanish individuals enter parenthood, and they tend to do so at later relative to their Swedish counterparts. There may be several explanations for the differences in the intensity and timing of partnership formation between Sweden and Spain. First, the variation in intensity of stable partnership formation may due to differences in the stage of SDT. The Nordic countries are often considered the leaders of the SDT, particularly in regard to ideological shifts toward individualism and self-realization, as well as the diffusion of cohabitation and non-marital childbearing. Despite these ideological changes, we find stable partnership formation occurs more frequently in Sweden than in Spain, where gender-egalitarian attitudes and norms have been on the rise in recent decades (Domínguez-Folgueras & Castro-Martín, 2013; García Pereiro et al., 2014; Muñoz & Recaño, 2011). Non-marital cohabitation as a path to family formation in Sweden is well-established and a notable difference between the two countries that may influence the intensity of stable partnership formation. Spain only started to observe notable increases in cohabitation since the 1990s, and marriage was the most common pathway to family formation before then (Domínguez-Folgueras & Castro-Martín, 2013; Martín-García, 2013). The declines in marriage observed in Spain over time, together with the delayed diffusion of cohabitation, likely contribute to the low intensity of partnership formation.

Partnership formation occurring later among the Spanish may be due to several features, one of them being Spain’s familistic welfare regime (Esping-Andersen, 1999) and strong family ties (Reher, 1998). These characteristics, for example, may have shaped how Spanish young adults cope with the rise in economic uncertainty following the 2008/2009 financial crisis. For instance, on average, young adults in Spain reside in their parental home until their early 30 s; meanwhile, Sweden’s generous welfare system provides support for young adults to be able to leave the parental home by age 18.

Unlike existing theoretical explanations emphasizing aspects such as historical trajectories, cultural/ideological change, gender equality, and economic uncertainty, our study focuses on explaining the fertility difference between Sweden and Spain by highlighting differences in partnership dynamics. Meaning, if partnership dynamics between the countries were more analogous, Swedish and Spanish fertility may not be as notably different, but instead, closer to their shared desired number of children (Sobotka & Beaujouan, 2014). This idea could contribute to theory development by focusing more attention on why couples are more likely to be formed in one country over another and why partnership formation can occur at earlier ages, rather than focusing on the characteristics of such couples. In terms of variation by gender, we find women and men tend to share a similar relationship between stable partnership formation and first birth, although, both events generally occur later for men.

Lastly, we acknowledge several limitations of our exploratory study—one of them being the inability to establish any causal inference. Additionally, while we recognize that the features associated with existing macro-level theories on cross-national fertility variation may influence both stable partnership formation and childbearing behaviors, implying a potentially confounding relationship, it is outside the scope of the paper to address this appropriately. Furthermore, the retrospective information used in our analysis is subject to recall bias. The start and end dates of stable partnerships may be particularly susceptible to this as exact dates of every instance of co-residence with an intimate partner may not be documented. When these dates are recalled inaccurately, the share of births that occur within or outside stable partnerships at a given age may be subject to bias. Another limitation is the size of the Swedish sample, which contributes to some of the fluctuations observed in our results (i.e., first-birth probabilities based on partnership status at a given age). The small sample size also hindered the possibility for any additional analysis by socio-economic characteristics, such as educational attainment. This may be interesting to explore in future research with larger datasets.

Despite the aforementioned shortcomings, however, our results still underline the need to place more attention towards the relationship between partnership dynamics and the transition to first birth—treating partnership dynamics as if it were a social proximate determinant of fertility (Esteve et al., 2020). This is especially relevant and important for future fertility research on societies with persisting levels of very low fertility. The influences of early partnership formation on childbearing found in the study also reveal the potential value of assisting young adults gain independence. Assistance, specifically, so that they may more easily leave the parental home. Here, leaving the parental home earlier might imply more time and opportunities for individuals to form stable unions and have a first child when desired—which is perhaps, at relatively early ages. This type of assistance is already provided in Sweden, and therefore, would, as our study suggests, have a large positive influence among developed countries continuously experiencing levels of very low fertility and delayed transitions to adulthood, such as Spain. These countries would also benefit from protecting childless, young adults from the continuing rise of economic uncertainty, as young adults, in particular, are negatively impacted during times of economic downturns (Sobotka et al., 2011).

Availability of data and materials

Data are available through the Generations and Gender Programme (https://www.ggp-i.org/).

Notes

In this paper, we use partnership and stable partnership interchangeably.

This cohort is selected since it is the most complete in terms of observable partnership formation and first births until age 40.

These results are based on the data used in our study from the Harmonized Histories dataset (Perelli-Harris et al., 2011). They are available upon request.

The strong gender imbalance of the original Spanish sample is due to its survey design. For further information, please refer to https://www.ine.es/en/metodologia/t20/fecundidad2018_meto_en.pdf.

The date of interview required all months to be imputed, albeit, this was done based on the actual timeframe in which interview were conducted for each respective survey (between March and June). Among our sample of native-born Swedish women born between 1962 and 1979, we randomly imputed month values for the following number of event occurrences by sex: stable partnership formation (N = 365 for women; N = 349 for men), partnership dissolution (N = 175 for women; N = 118 for men), and first birth (N = 1 for women; N = 1 for men). Note that the N here are based on the partnership histories of our sample, meaning the N represents an occurrence of a specific event.

Given the different survey years of the Swedish and Spanish data, 2012/2013 and 2018, respectively, and the 3-year censoring, some caution may be necessary when interpreting results of the Spanish sample due to the overlap with the 2008/2009 financial crisis. However, this is only in regards to the results of Spanish women and men born in the 1970s and not among those born in the 1960s. We are able to observe the partnership formation and childbearing behaviors of individuals in the latter, until at least age 39, prior to the crisis. Results of Spanish individuals born in the 1970s (in the Additional file 1), on the other hand, may need to be interpreted with this in mind.

Partnership formation and childbearing are closely related and potentially endogenous. To test to what extent endogeneity could be an issue for our study, we conducted a sensitivity analysis for childbearing intentions within the next 3 years among childless women based on their partnership status. Calculating an index of dissimilarity per age between Sweden and Spain, we find very low dissimilarity scores between childless women in a stable partnership (0.086 per age) and their counterparts who are not in a stable partnership (0.092 per age) at the time of survey; likewise, we find very low dissimilarity scores between childless men in a stable partnership (0.127 per age) and their counterparts who are not (0.064 per age) at the time of survey. Thus, we can conclude that childbearing intentions within the next 3 years are similar among childless individuals in Sweden and Spain despite stable partnership status, and that the potential endogeneity issues for these two groups may be minimal.

Please note that first-order TFR values have been rounded up to two decimal points. More precisely, the first-order TFRs are 0.877 and 0.708 for Swedish and Spanish women, respectively. The difference is 0.169. For Swedish and Spanish men, the first-order TFRs are 0.760 and 0.576, respectively. This difference is 0.184.

We also performed an additional, education-specific decomposition analysis. The results, however, were statistically imprecise due to the small sample size once age, birth cohort, gender, partnership status, and educational attainment were accounted for. The small sample size is particularly an issue for our selection of men and the low educated (for Sweden).

Abbreviations

- TFR:

-

Total fertility rate

- CFR:

-

Cohort fertility rate

- SDT:

-

Second Demographic Transition

- GGS:

-

Generations and Gender Survey

- SFS:

-

Spanish Fertility Survey

References

Alderotti, G., Vignoli, D., Baccini, M., & Matysiak, A. (2021). Employment instability and fertility in Europe: A meta-analysis. Demography, 58(3), 871–900.

Andersson, G. (2020). A review of policies and practices related to the 'highest-low' fertility of Sweden: A 2020 update. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography.

Baizán, P., Aassve, A., & Billari, F. C. (2003). Cohabitation, marriage, and first birth: The interrelationship of family formation events in Spain. European Journal of Population, 19(2), 147–169.

Balbo, N., Billari, F. C., & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population, 29(1), 1–38.

Bernardi, F., & Martínez-Pastor, J. I. (2011). Divorce risk factors and their variations over time in Spain. Demographic Research, 24, 771–800.

Billari, F. (2004). Becoming an adult in Europe: A macro (/micro)-demographic perspective. Demographic Research, S3(2), 15–44.

Billari, F., & Kohler, H. P. (2004). Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies, 58(2), 161–176.

Billari, F. C., Kohler, H. P., Andersson, G., & Lundström, H. (2007). Approaching the limit: Long-term trends in late and very late fertility. Population and Development Review, 33, 149–170.

Billari, F. C., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2010). Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood? Advances in Life Course Research, 15(2–3), 59–75.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Klijzing, E., Mills, M., & Kurz, K. (2005). Globalisation, uncertainty, and youth in society. Routledge.

Brzozowska, Z., Beaujouan, E., & Zeman, K. (2022). Is two still best? Change in parity-specific fertility across education in low-fertility countries. Population Research and Policy Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-022-09716-4

Buchmann, M. C., & Kriesi, I. (2011). Transition to adulthood in Europe. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 481–503.

Castro-Martín, T. (1992). Delayed childbearing in contemporary Spain: Trends and differentials. European Journal of Population/revue Européenne De Démographie, 8(3), 217–246.

Castro-Martín, T. (1993). Changing nuptiality patterns in contemporary Spain. Genus, 49(1/2), 79–95.

Coleman, D. (2004). Why we don’t have to believe without doubting in the" Second Demographic Transition"—some agnostic comments. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2, 11–24.

Coppola, L., & Di Cesare, M. (2008). How fertility and union stability interact in shaping new family patterns in Italy and Spain. Demographic Research, 18(4), 117–144.

Corijn, M., & Klijzing, E. (2001). Transitions to adulthood in Europe. Kluwer.

DallaZuanna, G., & Micheli, G. A. (Eds.). (2004). Strong family and low fertility: a paradox? New perspectives in interpreting contemporary family and reproductive behavior (Vol. 14). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Domínguez-Folgueras, M., & Castro-Martín, T. (2013). Cohabitation in Spain: No longer a marginal path to family formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(2), 422–437.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. OUP Oxford.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 1–31.

Esteve, A., Boertien, D., Mogi, R., & Lozano, M. (2020). Moving out the parental home and partnership formation as social determinants of low fertility. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 18, 1–15.

Esteve, A., Devolder, D., & Domingo, A. (2016). Childlessness in Spain: Tick Tock, Tick Tock, Tick Tock! Perspectives Demogràfiques, 1, 1–4.

Esteve, A., Lozano, M., Boertien, D., Mogi, R., & Cui, Q. (2021). Three decades of lowest-low fertility in Spain, 1991–2018. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/45j23.

Eurostat. (2022a). Statistics database: Fertility indicators [demo_find]. Eurostat.

Eurostat. (2022b). Statistics database: Estimated average age of young people leaving the parental household by sex [yth_demo_030]. Eurostat.

García Pereiro, T., Pace, R., & Grazia Didonna, M. (2014). Entering first union: The choice between cohabitation and marriage among women in Italy and Spain. Journal of Population Research, 31(1), 51–70.

Gauthier, A. H., Cabaço, S. L. F., & Emery, T. (2018). Generations and gender survey study profile. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 9(4), 456–465.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegard, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239.

Goldscheider, F., & Kaufman, G. (1996). Fertility and commitment: Bringing men back in. Population and Development Review, 22(Supplement), 87–99.

Hellstrand, J., Nisén, J., Miranda, V., Fallesen, P., Dommermuth, L., & Myrskylä, M. (2021). Not just later, but fewer: Novel trends in cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. Demography, 58(4), 1373–1399.

HFD. (2021). Human Fertility Database. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany), and Vienna Institute of Demography (Austria). Retrieved from https://www.humanfertility.org/cgi-bin/main.php.

Hiekel, N., Liefbroer, A., & Poortman, A.-R. (2014). Understanding diversity in the meaning of cohabitation across Europe. European Journal of Population, 30, 391–410.

Hoem, B., & Hoem, J. M. (1988). The Swedish family: Aspects of contemporary developments. Journal of Family Issues, 9(3), 397–424.

Holland, J. A. (2013). Love, marriage, then the baby carriage? Marriage timing and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 29(11), 275–306.

Joyner, K., Peters, H. E., Hynes, K., Sikora, A., Taber, J. R., & Rendall, M. S. (2012). The quality of male fertility data in major US surveys. Demography, 49(1), 101–124.

Kiernan, K. (1999). Cohabitation in Western Europe. Population Trends, 96, 25–32.

Kohler, H. P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–680.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14(1), 1–45.

Martín-García, T. (2013). Romulus and Remus or just neighbours? A study of demographic changes and social dynamics in Italy and Spain. Population Review, 52(1), 1–24.

Matysiak, A., Sobotka, T., & Vignoli, D. (2021). The great recession and fertility in Europe: A sub-national analysis. European Journal of Population, 37(1), 29–64.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

Miret-Gamundi, P. (1997). Nuptiality patterns in Spain in the eighties. Genus, 53(3/4), 183–198.

Muñoz, F., & Recaño, J. (2011). A century of nuptiality in Spain, 1900–2007. European Journal of Population/revue Européenne De Démographie, 27(4), 487–515.

Neels, K., Murphy, M., Bhrolcháin, M. N., & Beaujouan, E. (2017). Rising educational participation and the trend to later childbearing. Population and Development Review, 43(4), 667.

Neyer, G. (2013). Welfare states, family policies, and fertility in Europe. In The demography of Europe (pp. 29–53). Springer.

Ohlsson-Wijk, S. (2011). Sweden’s marriage revival: An analysis of the new-millennium switch from long-term decline to increasing popularity. Population Studies, 65, 183–200.

Ohlsson-Wijk, S., Turunen, J., & Andersson, G. (2020). Family forerunners? An overview of family demographic change in Sweden. In International Handbook on the Demography of Marriage and the Family (pp. 65–77). Springer.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2016). Education at a glance 2016. OECD.

Perelli-Harris, B., Kreyenfeld, M., & Kubisch, K. (2011). Technical manual for the Harmonized Histories database (MPIDR Working Paper No. 011). Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Puig-Barrachina, V., Rodríguez-Sanz, M., Domínguez-Berjón, M. F., Martín, U., Luque, M. Á., Ruiz, M., & Perez, G. (2020). Decline in fertility induced by economic recession in Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria, 34, 238–244.

Reher, D. S. (1998). Family ties in Western Europe: Persistent contrasts. Population and Development Review, 24(2), 203–234.

Reher, D., & Requena, M. (2019). Childlessness in twentieth-century Spain: A cohort analysis for women born 1920–1969. European Journal of Population, 35(1), 133–160.

Rendall, M. S., Clarke, L., Peters, H. E., Ranjit, N., & Verropoulou, G. (1999). Incomplete reporting of men’s fertility in the United States and Britain: A research note. Demography, 36(1), 135–144.

Schoumaker, B. (2017). Measuring male fertility rates in developing countries with Demographic and Health Surveys: An assessment of three methods. Demographic Research, 36, 803–850.

Schoumaker, B. (2019). Male fertility around the world and over time: How different is it from female fertility? Population and Development Review, 45, 459–487.

Sobotka, T. (2017). Childlessness in Europe: Reconstructing long-term trends among women born in 1900–1972. In M. Kreyenfeld & D. Konietzka (Eds.), Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, causes, and consequences (pp. 17–53). Springer.

Sobotka, T., & Beaujouan, E. (2014). Two Is best? The persistence of a two-child family ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40(3), 391–419.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Testa, M. R. (2007). Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe: Evidence from the Eurobarometer 2006 survey. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2007, 357–379.

Thomson, E., Lappegård, T., Carlson, M., Evans, A., & Gray, E. (2014). Childbearing across partnerships in Australia, the United States, Norway, and Sweden. Demography, 51(2), 485–508.

van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42(1), 1–59.

Vergauwen, J., Wood, J., De Wachter, D., & Neels, K. (2015). Quality of demographic data in GGS Wave 1. Demographic Research, 32(24), 723–774.

Vignoli, D., Bazzani, G., Guetto, R., Minello, A., & Pirani, E. (2020). Uncertainty and narratives of the future: A theoretical framework for contemporary fertility. Analyzing contemporary fertility (pp. 25–47). Springer.

Vignoli, D., Tocchioni, V., & Salvini, S. (2016). Uncertain lives: Insights into the role of job precariousness in union formation in Italy. Demographic Research, 35, 253–282.

Zeman, K., Beaujouan, É., Brzozowska, Z., & Sobotka, T. (2018). Cohort fertility decline in low fertility countries: Decomposition using parity progression ratios. Demographic Research, 38(25), 651–690.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

MN acknowledges support from the FI doctoral scholarship funded by the AGAUR (Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, Catalonia). QC and AE acknowledges support from the GLOBFAM project (RTI2018-096730-B-I00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN performed some analysis, wrote the paper, and edited the manuscript. AE developed the idea, guided the writing of the paper, and edited the manuscript. QC performed most of the analysis and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table A1.

Sample size by birth cohort for native-born Spanish and Swedish women and men. Fig. A1. Timing and intensity of event occurrences by age and birth cohort. Fig. A2. Hypothetical and actual prevalence of having a stable partner by age. Fig. A3. First-birth probability within the next 3 years at a given age (with 95% confidence intervals) based on partnership status. Fig. A4. Contribution of first-birth rate and partnership composition to first-birth differential by age group and cohort. Fig. A5 Observed and hypothetical first-birth rates if first stable partnerships were formed earlier/later. Fig. A6. Contribution of partnership-specific first-birth rate and composition to the first-birth differential by age group, 1965–1969.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishikido, M., Cui, Q. & Esteve, A. Partnership dynamics and the fertility gap between Sweden and Spain. Genus 78, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-022-00170-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-022-00170-w