Abstract

Background

Skipping meals, especially breakfast, is related to an increase in adiposity indicators, and this behavior is related to metabolic changes that predispose to the development of chronic diseases, recognized as major causes of death worldwide. The objective of the present paper was estimated the association between irregular breakfast habits with adiposity indices in schoolchildren and other lifestyle factors.

Methods

A population-based cross-sectional study was conducted in 2009–2010, including schoolchildren (n = 10,243) between 6 and 9 years old (51.3 % girls) from 18 districts of mainland Portugal. Breakfast habits were ascertained by asking a yes/no question (“Does your child eat breakfast regularly?”). An index estimated by performing principal component analysis was used to assess body adiposity from three different adiposity indicators (body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and the triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac skinfolds (used to estimate body fat percentage (BFP))). Multivariate logistic regression and multiple linear regression models were used to estimate the association of irregular breakfast habits with anthropometric indicators (BMI, BMI z score, WC, BFP, and adiposity index) and with children’s and parents’ lifestyle and socioeconomic characteristics.

Results

A total of 3.5 % of the children did not have breakfast regularly (girls 3.9 %; boys 3.1 %; P = 0.02). Among boys, irregular breakfast habits were associated with lower fathers’ education level, television time ≥2 h/day, and soft drink consumption ≥2 times/week. For girls, irregular breakfast habits were associated with lower mothers’ education level and physical inactivity, soft drink consumption ≥2 times/week, and <1 portion of milk/day. Multivariate linear models revealed a positive association between irregular breakfast habits with increased adiposity indicators among boys (BMI (kg/m2): β = 1.33; BMI z score: β = 0.48; WC (cm): β = 2.00; BFP (%): β = 2.20; adiposity index: β = 0.37; P < 0.01 for all). No significant association was found for girls.

Conclusions

Irregular breakfast habits were positively associated with boys’ increased global adiposity and were significantly affected by children’s and parents’ lifestyle-related behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The European Association for the Study of Obesity [1] estimates that 20 million European schoolchildren are overweight or obese. In Portugal, studies have also revealed a high prevalence of childhood obesity. Padez et al. [2] reported a nationwide prevalence of 31.5 % for overweight children (including obesity). In 2008, data published by the International Association for the Study of Obesity [3] also reported a high prevalence of overweight (including obesity) boys (23.5 %) and girls (21.6 %) in Portugal.

Obesity is a complex disease with a multifactorial etiology involving non-modifiable (age, sex, and family history) and modifiable factors, especially lifestyle-related behaviors such as physical activity and eating patterns [4], including meal habits, like skipping breakfast, which has become common among children and adolescents [5–7].

Regularly eating breakfast has been related to different childhood health benefits such as improved cognitive performance [8], preventing chronic diseases [9], and improved diet quality [10–13]. Conversely, the habit of skipping breakfast may be a marker of lifestyle behaviors, health and nutrition condition, and quality of life, because it has been associated with unhealthy lifestyle-related behaviors [12–14], higher body mass index (BMI) [10, 11, 13, 15–20], larger waist circumference [11, 17], high body fat percentage [13, 17], and other cardiometabolic risk factors [21, 22], all of which are often perpetuated in adult life [21, 23].

The aim of this study was to estimate the frequency of irregular breakfast habits among Portuguese schoolchildren and to assess the factors associated with this behavior and its association with adiposity indicators.

Methods

Subjects and design

This study was a secondary analysis of the Portuguese Prevalence Study of Obesity in Childhood (PPSOC), a cross-sectional study carried out with Portuguese schoolchildren between March 2009 and January 2010. The sample was randomly selected from each district of mainland Portugal using a proportional sampling strategy stratified by the age and sex of the children. The children were selected from the Ministry of Education database. More details on sampling can be found elsewhere [24–26].

Ethical approval for PPSOC was given by the Portuguese Commission for Data Protection which requires anonymity and nontransmissibility of data, corroborated by the Direcção Geral de Inovação e Desenvolvimento Curricular (Portuguese Institution of the Ministry of Education). In addition, the study was conducted according to the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki protocols, and the permission to collect the data was also obtained from the principal’s office of the schools and from the parents or guardians of the children, who signed an informed consent form indicating their consent to participate in the study.

Data collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire standardized answered by children’s parents. The questionnaire used in the present study was designed specifically for this research, and was designed to study the different aspects of the following characteristics: demographic and socioeconomic, lifestyle-related behaviors, eating habits, and other information on health and nutrition. The questionnaire content was evaluated by conducting a pilot test on a group of children similar to those in the study, and the questionnaire was revised based on the pilot results. To reduce the non-response rate, three visits were made to each school to examine previously absent students.

In this study, the following issues were considered with respect to the children: regular breakfast habits and number of meals per day, frequency of food consumption, physical activity outside of school and in physical education classes, time per day spent watching television (TV), and whether there was a TV set in the child’s bedroom. The following characteristics were investigated with respect to the parents: self-reported weight and height, education level, physical activity, and time spent watching TV. These measures have already been evaluated for their association with cardiovascular risk markers in previous publications [25, 26].

Regular breakfast habits were ascertained by the following yes/no question: “Does your child eat breakfast regularly?” The main interest of the study was in children who did not have breakfast regularly; namely, those who responded “no” were classified as “breakfast skippers” and those who responded “yes” as “breakfast eaters.” The number of daily meals was evaluated by asking if the child regularly had breakfast, lunch, an afternoon snack, and dinner.

The consumption of specific healthy and unhealthy eating markers was assessed through specific questions on the frequency of vegetable, soft drink, iced tea, and milk consumption. These questions had six response options for reporting the usual frequency of consumption ranging from never to two to three times/day. Fruit intake was measured with the question: “In the last week, how many portions of fruit did your child eat, on average, every day?”

To evaluate the time spent watching TV, the following question was used: “Indicate the time (in hours) that your child spent watching TV during weekdays and on Saturdays and Sundays” with the following answer options: none, up to 1 h, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, and more than 5 h. Total time spent watching TV per week was estimated as the average daily time watching TV, which was categorized into <2 and ≥2 h/day [27]. Additionally, parents were asked whether the child had a TV set in his or her bedroom (yes or no).

Time spent watching TV was evaluated for parents based on the same questions and criteria used to assess children’s TV time. The parents’ physical activity was evaluated based on the yes/no question “Do you regularly practice any sports?” Finally, parents’ education level (in years of education) was evaluated according to the highest level achieved by each parent; the results were grouped into the following categories: ≤6 years, 7–9 years, 10–12 years, and ≥13 years.

Anthropometric evaluation

Children’s anthropometric measurements were conducted by a trained team using standardized techniques [28]. Weight was measured using a digital scale with a precision of 0.1 kg (Seca 770, Medical Measuring Systems and Scales Ltd., Hamburg, Germany) and height was measured using a portable stadiometer with variation of 0.1 cm (Seca 217). The weight status was assessed by using the BMI (weight/stature2) z scores according to specific age and sex distributions from the World Health Organization [29]. The waist circumference (WC) was measured using a flexible, non-stretchable body measuring tape (Seca 201) at the midpoint between the anterior superior iliac crest and the last rib. Triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac skinfold thickness was measured using a Holtain compass (Holtain Ltd., Crymych, UK). The body fat percentage (BFP) was estimated using equations suggested for children and youths by Slaughter et al. [30] based on the triceps and subscapular skinfolds.

Parents’ weight status was evaluated by using the BMI according to the World Health Organization cutoff points [31] and based on self-reported weight and height values. The use of such self-reported measures has been previously validated [32, 33].

Data analysis

Student’s t test was used to assess differences in adiposity indicator means according to breakfast habits categories. The chi-square test was applied to assess the association between children’s and parents’ breakfast habits characteristics. Simple and multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the magnitude of the association between children’s and parents’ characteristics with skipping breakfast.

In this study, three different adiposity indicators (BMI, WC, and BFP) were considered because more accurate measurements of total adiposity (for example, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)) are less feasible in large epidemiological studies due to logistics and costs. Although the three adiposity indicators were not error-free, each measure provided specific information regarding body fat mass [34]. Based on this caveat and because of the high correlation among the three indicators and body fat (Spearman correlation coefficient >0.74), a principal component analysis was performed (similarly to a previous study performed by Ledoux et al. [34]) through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to obtain a construct (i.e., factor or latent variable) for the global adiposity based on these three anthropometric indicators. The EFA aims to identify the latent structure of a group of interrelated variables based on the understanding that if the variables are correlated, then they are correlated because the association results from a common but not directly observable characteristic [35, 36].

Thus, the principal component analysis developed using the three anthropometric indicators revealed a construct representing 91 % of the shared variance, with Cronbach’s α index equal to 0.88 and factors loadings equal to 0.96 for BMI, 0.95 for WC, and 0.94 for BFP, and in addition, high communalities were observed (0.93, 0.91, and 0.89, respectively). This construct was named “adiposity index” and was composed of the standardized means of the BMI, WC, and BFP as a representation of the global adiposity. Higher scores from the EFA were taken to indicate higher global adiposity.

Likewise, EFA allows estimating a score that weights highly correlated responses, parsimoniously representing the different variables analyzed [35]. Moreover, in the present study, another latent variable was used to adjust the linear regression models, which corresponded to the parents’ education level. This latent variable was chosen because of the observed correlation between the level of the mother’s and father’s education. EFA revealed a construct representing 82 % of the shared variance. The high communality (0.82 for both father’s and mother’s education) and Cronbach’s alpha values (0.78 for both the father’s and mother’s education) observed for the educational level of parents models revealed that this construct is appropriate to describe the latent correlation structure between the original variables.

Finally, to evaluate the association between irregular breakfast habits and body adiposity indicators (BMI, BMI z score, WC, BFP, and adiposity index), linear regression models were developed. Each indicator was considered as a dependent variable, and irregular breakfast habits were designated as the independent variable in each model. Children’s age, parental BMI, and the latent variable parents’ education level were included in the models because these factors exhibited significant correlation with the dependent variables in the univariate analysis (P < 0.01 for all). The statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) using the complex samples module.

Results

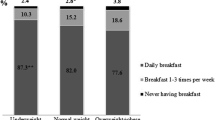

The participation rate was 63.6 %, and 10,624 children, residing in 18 districts of mainland Portugal, were assessed. Four percent (n = 381) of the participants did not answer the question on breakfast habits; therefore, this analysis was performed based on the data of 10,243 children (51 % girls) with a mean age of 8.03 years of age (standard deviation = 1.12). The frequency of irregular breakfast habits was 3.5 % and was higher among girls than boys. However, irregular breakfast habits were not associated with age (Table 1).

Irregular breakfast habits occurred less frequently in children of parents with higher levels of education and were higher among children whose parents did not engage in physical activity and whose parents watched TV for more than 2 h/day. Additionally, irregular breakfast habits were more common among children of overweight mothers (Table 1).

Breakfast skippers presented higher anthropometric indicator means than breakfast eaters. Irregular breakfast habits were more common among children who did not engage in physical activities outside of school, who watched TV for more than 2 h/day, and who had TV sets in their bedrooms. Moreover, irregular breakfast habits were associated with lower frequencies of fruit, vegetable, and milk consumption. Irregular breakfast habits were also associated with children who consumed fewer than four meals per day and with a higher frequency of soft drink and iced tea consumption (Table 1).

Because of the sex-based differences in the irregular breakfast habits, regression models were developed separately for boys and girls. After analysis of the crude logistic regression model, analysis of logistic regression models mutually adjusted for factors associated with the irregular breakfast habits was performed. In the adjusted models, for boys, the lower father’s education level (≤6 years: odds ratio (OR) = 2.64), the habit of watching TV ≥2 h/day (OR = 1.89), and frequent soft drink consumption (≥2 times/week: OR = 1.68) showed significant association with the irregular breakfast habits. For girls, significant ORs were observed for mother’s education level (≤6 years: OR = 2.11; 7–9 years: OR = 2.20; 10–12 years: OR = 2.67), and physical inactivity (OR = 2.07). Additionally, girls with a TV set in the bedroom (OR = 2.13), frequent soft drink consumption (≥2 times/week: OR = 1.63), and low milk consumption (<1 portion/day: OR = 1.83) had more chance of irregular breakfast habits (data not shown).

In the multiple linear regression models, a significant association between skipping breakfast and an increase in adiposity indicators was observed for boys independently of the confounding variables used as the control. No significant association between skipping breakfast and the adiposity indicators was observed in girls after adjusting for parents’ education level and weight status (Table 2).

Discussion

Irregular breakfast habits were associated with unhealthy lifestyle-related behaviors among Portuguese schoolchildren between 6 and 9 years of age. Children who regularly skipped breakfast were more likely to have a TV in the bedroom and consume soft drinks more frequently and milk less often than those who had regular breakfast habits. Additionally, children who skipped breakfast were also more likely to have parents who watched TV ≥2 h/day, have parents with lower level of education, and have mothers who did not engage in leisure physical activity. For boys, irregular breakfast habits were consistently associated with adiposity indicators. An increase of 1.33 kg/m2 in BMI, 0.48 standard deviation in BMI z score, 2.00 cm in WC, 2.20 % in BFP, and 0.37 points in the body adiposity index was observed for breakfast skippers even after adjusting for confounding factors. However, for girls, the association between irregular breakfast habits and body adiposity indicators was not significant after adjusting for parents’ characteristics.

The prevalence of skipping breakfast among Portuguese schoolchildren was lower than among German children of the same age range (13.4 %) [16], Australian children between 9 and 15 years (14.2 %) [21], Chinese children between 9 and 11 years (5.2 %) [12], and Spanish children between 8 and 17 years of age (6.5 %) [37]. These differences may be due to the data collection method and age range analyzed in each study. In Spain [37] and Australia [21], breakfast consumption information was collected through a meal frequency questionnaire, whereas in Germany [16] and China [12], specific questions regarding breakfast consumption similar to the one used in this study were used. Additionally, as older children were evaluated in the cited studies, higher frequency of breakfast skipping could expected, as previous studies have suggested that this habit increases with age [10–12, 37].

As observed in the current study, irregular breakfast habits have been commonly associated with a high prevalence of excess weight gain and higher WC and BFP [6, 10, 11, 13, 15–20], suggesting that irregular breakfast habits may be a potential risk factor or can enhance the effect of other risk factors for weight gain in children and adolescents. Thus, this habit can be a marker of an unhealthy lifestyle. One possible explanation for this association is that skipping specific meals may lead to a nutritional imbalance that could lead to lower postprandial energy expenditure. Decreased energy expenditure is associated with reduction in the thermogenic effect of food consumption, which can affect long-term weight gain [38, 39].

An important question to consider in cross-sectional studies is the causal relationship between irregular breakfast habits and the weight status [13], because it is possible that this behavior could be a consequence of excessive body weight [7]. Two longitudinal studies, Growing Up Today and Eating Among Teens, found that irregular breakfast frequency was associated with excessive body weight based on cross-sectional analysis but not on longitudinal analysis [14, 40].

However, other longitudinal studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term effects of irregular breakfast habits and the tendency for that behavior to continue from infancy to adult life [20, 21, 41]. The study Childhood Determinants of Adult Health found that irregular breakfast habits during childhood tends to continue through adulthood and that the skipping breakfast is associated with increased WC and higher fasting insulin values, homeostatic model assessment index, BMI indices, and the concentrations of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol fraction [21].

Based on the evidence that eating behaviors acquired during childhood have a high probability of continuing from childhood to adulthood [21, 23], identifying the factors that influence the presence of inadequate behaviors, such as irregular breakfast habits, is essential for planning intervention actions to minimize the long-term effects. In the present study, the parents’ characteristics such as education, weight status, and physical activity were associated with breakfast habits. Similar results were reported by Utter et al. [10], Tin et al. [12], and Pearson et al. [42]. According to Pearson et al. [42], parents’ characteristics influence children’s behavior because of the parental influence of the daily home environment, which is crucial to the development of eating behaviors.

The study Eating Among Teens found that weight concerns, lack of time to eat healthy foods at breakfast, socioeconomic status, and parents’ concerns about children’s health were factors observed at baseline that were associated with irregular breakfast habits 5 years later [41]. However, the associations tested between 1998 and 1999 and 2003 and 2004 did not remain significant after adjusting for those who skipped breakfast at the baseline analysis [41].

The association between irregular breakfast habits and unhealthy lifestyle-related behaviors such as more time spent watching TV and decreased physical activity, as observed with Portuguese children, was also observed in Pakistani children between 5 and 12 years of age [18] and Chinese children between 9 and 11 years of age [12] and between 9 and 18 years of age [13]. Based on these results, irregular breakfast habits may be considered not only a result of inadequate eating habits, but also an indicator of behaviors linked to an unhealthy lifestyle [7, 13], which can be used to identify population subgroups that require greater attention when planning public health actions and promoting healthy habits.

The limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. First, the current results are based on a cross-sectional study, making it possible to report associations only and not a causal relationship between independent variables and the outcomes observed. However, associations similar to the main correlations observed in the present study, especially between irregular breakfast habits and an increase in body adiposity indicators, have also been observed in longitudinal studies [20, 21]. Second, the question used to evaluate breakfast habits was meant to capture habitual consumption but may have excluded children who occasionally skip breakfast, thus resulting in lower prevalence than actually exists. However, similar questions were also used in other studies [12, 15, 16]. Nevertheless, it can be inferred that this question presented high sensitivity to capture the regular omission of breakfast, because mothers whose children omit this meal occasionally likely would not answer that their children regularly skip breakfast, and this answer also would not be affected by breakfast consumption on the day of data collection. Thus, it is believed that the children that regularly skip breakfast do have this habit; therefore, this type of question may be important for surveillance studies on risk behaviors identifying children that must be accompanied on intervention studies.

Third, there was lack of specific information on the nutritional quality of the breakfasts these children were eating. However, previous studies that evaluated this relationship found that children who regularly consumed breakfast had a significantly higher intake of fruits, vegetables, milk and dairy products, fiber, vitamins, and minerals [10, 11]. Conversely, skipping breakfast has been associated with a higher consumption of fat, sweets, junk food, sugary drinks, and fried foods [10–13]. Finally, there was a considerable rate of non-response in this study (42.6 %) and there was no information available on the characteristics of non-respondents. Therefore, the study generalizability is compromised and under- or overestimation may have occurred.

Despite these limitations, the results of the present study have important implications for public health and the promotion of children’s health in Portugal. First, this study analyzed data of a representative sample of Portuguese schoolchildren, a group that presents with a high prevalence of being overweight (28 % among children between 3 and 10 years of age [25]). However, the increasing frequency of irregular breakfast habits and its association with weight gain observed in other countries justify efforts to include incentives for the daily consumption of breakfast in actions promoting healthy eating habits, especially in subgroups at greater risk of weight gain or skipping breakfast, such as the schoolchildren studied here.

Understanding the relationship between inadequate eating habits such as irregular breakfast habits may help develop future intervention programs to control the child obesity epidemic and promote healthy lifestyle habits. Future studies are necessary, with a focus on the importance of studies with longitudinal designs and representative samples such as the population evaluated in the present study. These future studies should aim to clarify the role of consuming breakfast on the long-term development and prevention of childhood obesity. Another important aspect to consider is the incorporation of information on the nutritional quality of the breakfast to further determine the effects of consuming breakfast of differing nutritional quality on child development.

Conclusions

Among Portuguese schoolchildren, irregular breakfast habits were associated with unhealthy lifestyle and lower parental levels of education. Additionally, an association between irregular breakfast habits and increased occurrence of overweight and global body adiposity was observed. The results suggest that irregular breakfast habits may be a marker of unhealthy lifestyle that should be monitored, and that the evaluation the breakfast habits may help identify groups at higher risk of developing health problems and may support the design of intervention programs.

References

European Association for the Study of Obesity. Childhood Obesity. 2015. http://www.easo.org/task-forces/childhood-obesity-cotf/facts-statistics/. Accessed 09 Sept 2015.

Padez C, Fernandes T, Mourão I, Moreira P, Rosado V, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in 7-9-year-old portuguese children: trends in body mass index from 1970–2002. Am J Hum Biol. 2004;6:670–8.

Sardinha LB, Santos R, Vale S, Silva AM, Ferreira JP, Raimundo AM, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Portuguese youth: a study in a representative sample of 10-18-year-old children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e124–8.

Trovato GM. Behavior, nutrition and lifestyle in a comprehensive health and disease paradigm: skills and knowledge for a predictive, preventive and personalized medicine. EPMA J. 2012;3:8.

Popkin BM. Contemporary nutritional transition: determinants of diet and its impact on body composition. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70:82–91.

Affenito SG. Breakfast: a missed opportunity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:565–9.

Pivik RT, Dykman RA, Tennal K, Gu Y. Skipping breakfast: gender effects on resting heart rate measures in preadolescents. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:270–80.

Wesnes KA, Pincock C, Scholey A. Breakfast is associated with enhanced cognitive function in schoolchildren. An internet based study. Appetite. 2012;59(3):646–9.

Szajewska H, Ruszczynski M. Systematic review demonstrating that breakfast consumption influences body weight outcomes in children and adolescents in Europe. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:113–9.

Utter J, Scragg R, Mhurchu CN. At-home breakfast consumption among New Zealand children: associations with body mass index and related nutrition behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:570–6.

Deshmukh-Taskar PR, Nicklas TA, O’Neil CE, Keast DR, Radcliffe JD, Cho S. The relationship of breakfast skipping and type of breakfast consumption with nutrient intake and weight status in children and adolescents: the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:869–78.

Tin SPP, Ho SY, Mak KH, Wan KL, Lam TH. Lifestyle and socioeconomic correlates of breakfast skipping in Hong Kong primary 4 schoolchildren. Prev Med. 2011;52:250–3.

So HK, Nelson EAS, Li AM, Guldan GS, Yin J, Ng PC, et al. Breakfast frequency inversely associated with BMI and body fatness in Hong Kong Chinese children aged 9-18 years. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:742–51.

Timlin MT, Pereira MA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Breakfast eating and weight change in a 5-year prospective analysis of adolescents: Project EAT (Eating Among Teens). Pediatrics. 2008;21:638–45.

Hirschler V, Buzzano K, Erviti A, Ismael N, Silva S, Dalamon R. Overweight and lifestyle behaviors of low socioeconomic elementary school children in Buenos Aires. BMC Pediatr. 2009;24:9–17.

Nagel G, Wabitsch M, Galm C, Berg S, Brandstetter S, Fritz M, et al. Determinants of obesity in the Ulm research on metabolism, exercise and lifestyle in children (URMEL-ICE). Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:1259–67.

Isacco L, Lazaar N, Ratel S, Thivel D, Aucouturier J, Doré E, et al. The impact of eating habits on anthropometric characteristics in French primary school children. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:835–42.

Mushtaq MU, Gull S, Mushtaq K, Shahid U, Shad MA, Akram J. Dietary behaviors, physical activity and sedentary lifestyle associated with overweight and obesity, and their socio-demographic correlates, among Pakistani primary school children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:130.

O’Dea JA, Wagstaff S. Increased breakfast frequency and nutritional quality among schoolchildren after a national breakfast promotion campaign in Australia between 2000 and 2006. Health Educ Res. 2011;26:1086–96.

Tin SP, Ho SY, Mak KH, Wan KL, Lam TH. Breakfast skipping and change in body mass index in young children. Int J Obes. 2011;35:899–906.

Smith KJ, Gall SL, McNaughton SA, Blizzard L, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Skipping breakfast: longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in the childhood determinants of adult health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1316–25.

Freitas Júnior IF, Christofaro DG, Codogno JS, Monteiro PA, Silveira LS, Fernandes RA. The association between skipping breakfast and biochemical variables in sedentary obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2012;161:871–4.

Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, Adamson AJ, Mathers JC. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;70:266–84.

Jago R, Stamatakis E, Gama A, Carvalhal IM, Nogueira H, Rosado V, et al. Parent and child screen-viewing time and home media environment. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:150–8.

Bingham DD, Varela-Silva MI, Ferrão MM, Augusta G, Mourão MI, Nogueira H, et al. Socio-demographic and behavioral risk factors associated with the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in Portuguese children. Am J Hum Biol. 2013;25:733–42.

Stamatakis E, Coombs N, Jago R, Gama A, Mourão I, Nogueira H, et al. Type-specific screen time associations with cardiovascular risk markers in children. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:481–8.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on public education. Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–6.

Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988.

World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards (version 3.2.2, January 2011). 2011. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/]. Accessed 09 Sept 2015.

Slaughter MH, Lohman TG, Boileau RA, Horswill CA, Stillman RJ, Van Loan MD, et al. Skinfold equations for estimation of body fatness in children and youth. Hum Biol. 1988;60:709–23.

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. WHO Technical Report Series no. 894. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

Bolton-Smith C, Woodward M, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Morrison C. Accuracy of the estimated prevalence of obesity from self reported height and weight in an adult Scottish population. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2000;54:143–8.

Fonseca MJM, Faerstein E, Chor D, Lopes CS. Validity of self-reported weight and height and the body mass index within the “Pró-saúde” study. Rev Saude Publica. 2004;38:392–8.

Ledoux T, Watson K, Baranowski J, Tepper BJ, Baranowski T. Overeating styles and adiposity among multiethnic youth. Appetite. 2011;56:71–7.

Chavance M, Escolano S, Romon M, Basdevant A, de Lauzon-Guillain B, Charles MA. Latent variables and structural equation models for longitudinal relationships: an illustration in nutritional epidemiology. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:37.

Marôco J. Análise fatorial. In: Pêro P, editor. Análise estatística com o SPSS Statistics. Portugal: ReportNumber, Lda; 2010. p. 469–528.

Monteagudo C, Palacín-Arce A, Bibiloni MM, Pons A, Tur JA, Olea-Serrano F, et al. Proposal for a breakfast quality index (BQI) for children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:639–44.

Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA. Decreased thermic effect of food after an irregular compared with a regular meal pattern in healthy lean women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:653–60.

Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA. Beneficial metabolic effects of regular meal frequency on dietary thermogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and fasting lipid profiles in healthy obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:16–24.

Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Gillman MW, Field AE, Colditz GA. Longitudinal study of skipping breakfast and weight change in adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1258–66.

Bruening M, Larson N, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P. Predictors of adolescent breakfast consumption: longitudinal findings from Project EAT. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43:390–5.

Pearson N, MacFarlane A, Crawford D, Biddle SJ. Family circumstance and adolescent dietary behaviours. Appetite. 2009;52:668–74.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant of the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia - FCT (FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-007483). This report is also research arising from a “doctorate sandwich” supported by CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil (process number: 8349/12-6). However, the FCT and the CAPES Foundation had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Authors’ contributions

PRMR contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, the drafting, writing, and revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. RAP contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. AMSS, AG, IMC, HN, and VRM contributed to design the data collection instruments, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript. CP contributed to the conception and design of the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodrigues, P.R.M., Pereira, R.A., Santana, A.M.S. et al. Irregular breakfast habits are associated with children’s increased adiposity and children’s and parents’ lifestyle-related behaviors: a population-based cross-sectional study. Nutrire 41, 8 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-016-0009-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-016-0009-7