Abstract

In this paper, we describe the potential of simulation to improve hospital responses to the COVID-19 crisis. We provide tools which can be used to analyse the current needs of the situation, explain how simulation can help to improve responses to the crisis, what the key issues are with integrating simulation into organisations, and what to focus on when conducting simulations. We provide an overview of helpful resources and a collection of scenarios and support for centre-based and in situ simulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Simulation has a huge potential to help managing the global COVID-19 crisis in 2020 and in potentially similar future pandemics. Simulation can rapidly facilitate hospital preparation and education of large numbers of healthcare professionals and students of various backgrounds and has proven its value in many settings [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. It can be utilised to scale-up workforce capacity through experiential learning. Simulation and simulation facilitators can also contribute to the optimisation of work structures and processes. In this article, we describe this potential and share ways in which it could be utilised in healthcare organisations under pressure.

The role of simulation in the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 outbreak is a textbook case for the use of simulation and an opportunity for simulation to play to its strengths. This was seen in previous crisis events inside and outside of healthcare [11,12,13,14]. The demands of clinical care are sensitive to errors, and the stakes are high if errors occur. The pandemic places a high personal risk for healthcare professionals themselves, potentially triggering fear of getting infected or spreading the infection to their own family members. Training in the clinical environment is risky because of the danger of contamination. Practice through simulation can reduce the cognitive load [15] of the staff involved in patient care, thereby helping to mitigate error in times of pressure and exhaustion.

The rapid onset of COVID-19 and its huge burden on resources requires coordinated action across many areas of the healthcare system including staffing, equipment supply chains, bed management, diagnostic capabilities, nursing and medical treatment, infection control, and hygiene skills compliance [6]. In terms of equipment and human resources, the demand exceeds what is available in most current healthcare systems [16, 17]. Therefore, smart and novel ways of increasing and upskilling a workforce, locating and supplying equipment, and optimising work systems are needed. Simulation can play a vital role in solving these problems, and simulation educators often possess valuable capabilities to facilitate the necessary analytical work required to match (learning) needs, content, and methods to implement effective interventions. Given the urgency of the situation, careful analysis of learning needs and simulation focus points are critical, so that procedures are followed correctly and that there is appropriate use of resources to enable effective patient care.

Aim of this paper

The aim of the current paper is to present tips and resources for the use of simulation to make a difference in the response to COVID-19. Collectively, the authors have significant experience in analysing work systems, in interacting with leaders and clinicians at various levels, and in creating simulation activities for basic education, advanced training, and research. We also have been intensely involved in coordinating, designing, and running COVID-19 simulations and other activities for our organisations in various roles. We will draw on this expertise and our knowledge of resources to support other simulation initiatives to respond to COVID-19. We will provide examples in different areas, in order to stimulate the systematic analysis in different contexts. We do not aim for a complete overview. The current situation has accelerated many simulation-related developments, but many of the underlying principles discussed in this paper will still be relevant once the crisis is over.

Putting plans into practice

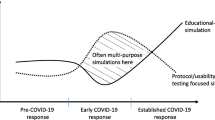

Simulation can play a role in the response to COVID-19 on several layers: firstly, the (re-)qualification of personnel to function quickly in a variety of positions (educational focus). Secondly, simulation can also play a role to understand and optimise workflows, bottlenecks, dependencies, etc. (system focus). Finally, simulation and the related abilities of simulation facilitators can help in supporting healthcare professionals in dealing with the emotional strain of the situation (personal focus). We will unfold all of these aspects in more detail.

A beneficial first step is to consider what resources are available in terms of people, equipment, and locations. Often, simulation facilitators are trained in a systems-approach to safety, understand the importance of feedback, and are able to guide people through goal-oriented reflections. They frequently have an in-depth knowledge of the hospital structure, processes, and people. Facilitators can use their skills to help healthcare units identify key problems that need to be dealt with. They can help find solutions and connect different people and departments that would benefit from collaboration.

It is important to listen carefully and identify the key clinical issues and to design simulations for the exact problems at hand, rather than “resell” existing courses from the shelves. Even in time-pressured situations, we believe that systematic analysis of (learning) needs and careful selection of contents and methods are crucial [18,19,20]. Simulation should be seen as an interventive tool for training and as a diagnostic tool for the analysis of work structures and processes [21]. Findings from training sessions can help in identifying and shaping learning goals, staff preparedness, improving systems and protocols, and ultimately patient safety.

Tips and resources

In this section, we provide reflective questions and focus points that can guide you on how to develop localised approaches to specific challenges. There are other publications providing practical guidance for simulation activities focusing on hygiene issues, putting on and removing protective gear, taking COVID-19-related history from patients and relatives, decision-making and triaging, escorting patients, and self-protection against contamination [22, 23].

Although learning needs analysis can feel like an unneeded luxury in times of crisis, it is during such time-pressured situations that the increased precision brought by a coherent, if quick, needs analysis can yield significant benefits. Table 1 provides questions and focus points that can be used when analysing the (learning) needs of departments or when observing and debriefing clinical and simulation-based work. The questions aim to facilitate thinking about connections and feedback loops between departments, people, and initiatives. For all ideas, findings, and insights, you should consider the following:

-

Who in your organisation needs to know about this?

-

What problems, errors, and challenges did you observe?

-

What were the reasons for them?

-

What can be done to avoid them or to mitigate their negative outcomes?

-

What are good ideas that should be shared?

-

What is the “corridor of normal performance” [26] in terms of time-on-task or variety of approach (e.g. how long does donning and doffing of personal protection equipment typically take, and how do different people go about it)?

When conducting the needs analysis, you might assume that you know the organisation quite well already, if you have already run simulation projects in your organisation. However, a rapidly developing crisis situation can change things drastically—consider, for example, the shortage of very basic equipment. Take into account that an infectious disease crisis has the potential to change some very fundamental framework conditions that you may have previously taken for granted.

Not only does simulation training provide learning at the individual level, it has an integral part to play in systems testing. Every scenario holds the potential to learn and improve on the systems level [24, 27], and simulation can be a useful tool in the development of new standard operating procedures and policies needed to respond to the COVID-19 crisis.

Table 2 provides an overview of possible focus points, learning goals, target groups, methods, and practical considerations to improve the response to COVID-19. The immediate focus point for simulation typically is seen as educational. Whilst this focus is important, it does not make use of all the potential that simulation offers. Therefore, Table 2 also provides system and personal focus [29,30,31]. Besides the points mentioned in the tables, it is important that participants are familiar with the general procedures and actual practices within their organisation or department and that they keep updated with any rapid developments. Simulation and debriefs also have great potential to help healthcare workers deal with the emotional stress that they might be currently experiencing [32, 33].

Be sure to teach in accordance with the organisation’s philosophy, policies, and procedures, especially as the latter two are changing rapidly in the dynamic environment of a crisis. It might be that different stakeholders assign different priorities to different areas, and facilitation skills can help to broker compromises. Whenever possible, consider whether you can capture several potential learning goals simultaneously in each scenario or training event. For instance, because healthcare professionals might worry about getting infected themselves, it might be reassuring to incorporate a short demonstration and try-out of how resilient personal protection devices can be in different movement situations at the end of a training session.

The level of ambition for the quality of simulation activities might generate discussion among stakeholders. In predicaments such as the COVID-19 outbreak, simulation activities may have to aim for being “good enough”, rather than “perfect” [34]. Many of the issues addressed in Table 2 might not be the direct target of your simulation activities, but you still might be able to trigger and support changes in the organisation.

Collaboration between stakeholders

The unfolding crisis poses huge challenges but also opens many windows of opportunity. It is impressive to see how quickly resources are provided, borrowed, and shared when they are being used to prepare for the challenges to come. Simulation centres have a key role through the skills of their facilitators, with their connection to clinical practice and with providing educational equipment to be used in various settings. Table 3 provides some tips on how to interact with different stakeholders in and beyond your organisation [27, 39, 40]. This is also to make sure that the use of simulation across all three focus areas is aligned with the organisational philosophy, policies, and procedures and that work as imagined corresponds as much as possible to work as done [41,42,43]. The table emphasises how an effective communication flow can help in running relevant scenarios, by carefully collecting information from the clinic. It also shows how communication from the simulation team into the organisation can help in discovering and managing problematic system elements, or great ideas that should be shared.

Preparing, running, and debriefing simulations to improve responses for COVID-19

Importantly, most simulation educators have significant training and experience that make them ideally suited to leading and working through this crisis. Do not forget what you already know. Most principles of simulation apply for the current situation. Table 4 provides some practical considerations to prepare, run, and debrief scenarios with a special focus on COVID-19. We assume here that you are working within an established simulation programme and therefore do not go into all methodological details [47,48,49]. Make sure that you do not introduce risks by simulating in situ [50, 51], and try to get all the help you can. Remember pre-graduate students can help too [46]. Use your experience from planning and organising debriefings, as debriefing is central to learning through simulation [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. The time-pressured nature of the current situation might benefit from methods which are flexible in terms of timing [62, 63].

Further material

COVID-19-related scenario scripts and a collection of other resources can be found at www.safer.net. A collection of scenarios from King’s College Hospital in London can be found as an online supplement. Further collections of supporting material are rapidly being circulated in online communities of practice and through social media. Use them when it is appropriate to do so, as it can save time during a crisis situation. As always, these resources will need to be adapted to local procedures.

Long-term considerations

Remember to keep also the long-term perspective in mind: the crisis will subside and some sense of a normal clinical service will resume, potentially with a backlog of necessary activity that has been put on hold during the crisis. How will you, your colleagues, and the overall system get back to normal after this situation? What might “normal” might look like? It may very well be quite different than it has been before the crisis. Is there an opportunity to have a lasting effect on, for example, patient safety, the well-being of healthcare professionals, or work processes? Take the opportunity to nurture the connections with people in clinical departments—they can help to get the job done in clinical practice, especially when it needs to be done quickly. Do not forget to make some notes for the future: aspects of the crisis experience can help you to develop plans on how to use simulation to prepare organisations to respond to the unexpected and the extraordinary in the future.

Summary of key points

-

Ensure the needs of the organisation are well understood.

-

Consider connections and establish feedback loops.

-

Know what resources are available in terms of material, equipment, and people.

-

Find the balance between providing learning and providing systems improvement.

-

Be aware of the potential extra load put on learners, educators, departments, clinical units, and the organisation during a crisis.

-

Consider the knowledge and skills your learners require, as well as their well-being. Help them to protect themselves and to save valuable resources.

-

Spending adequate time on the analysis of the problem is an investment towards solutions that will make a difference. Balance being fast with being thorough.

Conclusion

Simulation has great potential to help mitigate the negative effects of the COVID-19 crisis and potentially for future crisis situations. The examples and tips provided in this paper can help simulation to harvest this potential in the interest of patients, relatives, the public, and—last but not least—healthcare professionals.

Availability of data and materials

We do not report empirical findings as such. Therefore, no more data or materials are available.

References

Brazil V, Purdy EI, Bajaj K. Connecting simulation and quality improvement: how can healthcare simulation really improve patient care? BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(11):862–5.

Brazil V. Translational simulation: not ‘where?’ but ‘why?’ A functional view of in situ simulation. Adv Simul (Lond). 2017;2:20.

Speirs C, Brazil V. See one, do one, teach one: is it enough? No Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30(1):109–10.

Ajmi SC, Advani R, Fjetland L, Kurz KD, Lindner T, Qvindesland SA, et al. Reducing door-to-needle times in stroke thrombolysis to 13 min through protocol revision and simulation training: a quality improvement project in a Norwegian stroke centre. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(11):939–48.

Cook DA, Andersen DK, Combes JR, Feldman DL, Sachdeva AK. The value proposition of simulation-based education. Surgery. 2018;163(4):944–9.

Lavelle M, Reedy GB, Attoe C, Simpson T, Anderson JE. Beyond the clinical team: evaluating the human factors-oriented training of non-clinical professionals working in healthcare contexts. Adv Simul (Lond). 2019;4:11.

Cook DA, Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Szostek JH, Wang AT, et al. Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-based education: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. 2013;35(1):e867–98.

Bearman M, Greenhill J, Nestel D. The power of simulation: a large-scale narrative analysis of learners’ experiences. Med Educ. 2019;53(4):369–79.

Petrosoniak A, Brydges R, Nemoy L, Campbell DM. Adapting form to function: can simulation serve our healthcare system and educational needs? Adv Simul (Lond). 2018;3:8.

Paige JT, Terry Fairbanks RJ, Gaba DM. Priorities related to improving healthcare safety through simulation. Simul Healthc. 2018;13(3S Suppl 1):S41–50.

Ziv A, Wolpe PR, Small SD, Glick S. Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Simul Healthc. 2006;1(4):252–6.

Gaba DM. Simulation as a critical resource in the response to Ebola virus disease. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(6):337–8.

Biddell EA, Vandersall BL, Bailes SA, Estephan SA, Ferrara LA, Nagy KM, et al. Use of simulation to gauge preparedness for Ebola at a free-standing children’s hospital. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(2):94–9.

Argintaru N, Li W, Hicks C, White K, McGowan M, Gray S, et al. An active shooter in your hospital: a novel method to develop a response policy using in situ simulation and video framework analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1–9.

Reedy GB. Using cognitive load theory to inform simulation design and practice. Clin Simul Nursing. 2015;11(8):355–60.

Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – sixth update – 12 March 2020. 2020 [Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/rapid-risk-assessment-novel-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-pandemic-increased#no-link.

Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum development for medical education : a six-step approach. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. xii. p. 253.

Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum development for medical education : a six-step approach. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016. xii. p. 300.

Sollid SJM, Dieckman P, Aase K, Soreide E, Ringsted C, Ostergaard D. Five topics health care simulation can address to improve patient safety: results from a consensus process. J Patient Saf. 2019;15(2):111–20.

Mehl K. Simulation as a tool for training and analysis. In: Dieckmann P, editor. Using Simulation for Education, Training and Research. Lengerich: Pabst; 2009. p. 139–51.

Nickson C. COVID-19 airway management: better care through simulation 2020 [Available from: https://litfl.com/covid19-airway-management-better-care-through-simulation/.

Li L, Lin M, Wang X, Bao P, Li Y. Preparing and responding to 2019 novel coronavirus with simulation and technology-enhanced learning for healthcare professionals: challenges and opportunities in China. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanced Learning. 2020:bmjstel-2020-000609.

Hollnagel E. FRAM, the functional resonance analysis method : modelling complex socio-technical systems. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington: Ashgate; 2012. x. p. 142.

Hallihan G, Caird JK, Blanchard I, Wiley K, Martel J, Wilkins M, et al. The evaluation of an ambulance rear compartment using patient simulation: issues of safety and efficiency during the delivery of patient care. Appl Ergon. 2019;81:102872.

Dieckmann P, Patterson M, Lahlou S, Mesman J, Nystrom P, Krage R. Variation and adaptation: learning from success in patient safety-oriented simulation training. Adv Simul (Lond). 2017;2:21.

Patterson MD, Geis GL, Falcone RA, LeMaster T, Wears RL. In situ simulation: detection of safety threats and teamwork training in a high risk emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(6):468–77.

Zhang C, Zhang C, Grandits T, Harenstam KP, Hauge JB, Meijer S. A systematic literature review of simulation models for non-technical skill training in healthcare logistics. Adv Simul (Lond). 2018;3:15.

Reid-McDermott B, Browne M, Byrne D, O’Connor P, O'Dowd E, Walsh C, et al. Using simulation to explore the impact of device design on the learning and performance of peripheral intravenous cannulation. Adv Simul (Lond). 2019;4:27.

Gaba DM. Do as we say, not as you do: using simulation to investigate clinical behavior in action. Simul Healthc. 2009;4(2):67–9.

Minor S, Green R, Jessula S. Crash testing the dummy: a review of in situ trauma simulation at a Canadian tertiary centre. Can J Surg. 2019;62(4):243–8.

Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020.

Klein G, Hintze N, Saab D. Thinking inside the box: the ShadowBox method for cognitive skill development; 2013.

Hollnagel E. The ETTO principle : efficiency-thoroughness trade-off: why things that go right sometimes go wrong. Burlington: Ashgate; 2009. vii. p. 150.

Gawande A. Keeping the coronavirus from infecting health-care workers. The New Yorker. 2020;Online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/keeping-the-coronavirus-from-infecting-health-care-workers.

Edwards S, Tuttle N. Using stakeholder input to inform scenario content: an example from physiotherapy. Adv Simul (Lond). 2019;4(Suppl 1):20.

Wehbi NK, Wani R, Yang Y, Wilson F, Medcalf S, Monaghan B, et al. A needs assessment for simulation-based training of emergency medical providers in Nebraska, USA. Adv Simul (Lond). 2018;3:22.

Paltved C, Bjerregaard AT, Krogh K, Pedersen JJ, Musaeus P. Designing in situ simulation in the emergency department: evaluating safety attitudes amongst physicians and nurses. Adv Simul (Lond). 2017;2:4.

Patterson MD, Blike GT, Nadkarni VM. In situ simulation: challenges and results. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 3: Performance and Tools). Rockville: Advances in Patient Safety; 2008.

Spanos SL, Patterson M. An unexpected diagnosis: simulation reveals unanticipated deficiencies in resident physician dysrhythmia knowledge. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(1):21–3.

Hollnagel E. Safety-I and safety-II : the past and future of safety management. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company; 2014. p. 187.

Hollnagel E. Safety-II in practice : developing the resilience potentials. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge; 2017. cm p.

Patterson M, Dieckmann P, Deutsch E. Simulation: a tool to detect and traverse boundaries. In: Braithwaite J, Hollnagel E, Hunte GS, editors. Working Across Boundaries - Resilient Health Care Volume. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2019. p. 67–77.

Hayden EM, Wong AH, Ackerman J, Sande MK, Lei C, Kobayashi L, et al. Human factors and simulation in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(2):221–9.

Flin R, Maran N. Basic concepts for crew resource management and non-technical skills. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2015;29(1):27–39.

Viggers S, Ostergaard D, Dieckmann P. How to include medical students in your healthcare simulation centre workforce. Adv Simul (Lond). 2020;5:1.

Nestel D, Jolly B, Watson M, Kelly M. Healthcare simulation education: evidence, theory & practice. Chichester; Hoboken: Wiley; 2017.

Chiniara G. Clinical simulation: education, operations and engineering. 2nd ed. Waltham: Elsevier; 2019. p. cm.

Dieckmann P, Gaba D, Rall M. Deepening the theoretical foundations of patient simulation as social practice. Simul Healthc. 2007;2(3):183–93.

Raemer D, Hannenberg A, Mullen A. Simulation safety first: an imperative. Adv Simul. 2018;3(1):25.

Bajaj K, Minors A, Walker K, Meguerdichian M, Patterson M. “No-go considerations” for in situ simulation safety. Simul Healthc. 2018;13(3):221–4.

Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2007;2(2):115–25.

Schertzer K, Patti L. In situ debriefing in medical simulation. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2020.

Lee J, Lee H, Kim S, Choi M, Ko IS, Bae J, et al. Debriefing methods and learning outcomes in simulation nursing education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;87:104345.

Salik I, Paige JT. Debriefing the interprofessional team in medical simulation. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2020.

Felix HM, Simon LV. Debriefing theories and philosophies in medical simulation. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2020.

Halamek LP, Cady RAH, Sterling MR. Using briefing, simulation and debriefing to improve human and system performance. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43(8):151178.

Dube MM, Reid J, Kaba A, Cheng A, Eppich W, Grant V, et al. PEARLS for systems integration: a modified PEARLS framework for debriefing systems-focused simulations. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(5):333–42.

Bajaj K, Meguerdichian M, Thoma B, Huang S, Eppich W, Cheng A. The PEARLS healthcare debriefing tool. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):336.

Sawyer T, Eppich W, Brett-Fleegler M, Grant V, Cheng A. More than one way to debrief: a critical review of healthcare simulation debriefing methods. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(3):209–17.

Jaye P, Thomas L, Reedy G. ‘The Diamond’: a structure for simulation debrief. Clin Teach. 2015;12(3):171–5.

Taras J, Everett T. Rapid cycle deliberate practice in medical education - a systematic review. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1180.

Schober P, Kistemaker KRJ, Sijani F, Schwarte LA, van Groeningen D, Krage R. Effects of post-scenario debriefing versus stop-and-go debriefing in medical simulation training on skill acquisition and learning experience: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):334.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the tremendous work that healthcare professionals around the world are doing currently. The work from Kings College Hospital was spear-headed by the ACET (Anaesthetics, Critical Care, Emergency Medicine and Trauma) Education Team, especially Simon Calvert, Iain Carroll, and Richard Fisher. In Stavanger, the work has been led by a group consisting of people from the educational department at Stavanger University Hospital, staff from SAFER simulation centre, and from the regional simulation coordinating unit. We thank the editorial team for the quick turn around and very helpful feedback on previous versions of the article.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors developed and refined the ideas in this paper. Dieckmann wrote the first draft, and all authors discussed it actively and revised the draft until the final agreement on the submitted version. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We do not report any person-related data but present a conceptual piece. Ethical approval and consent to participate are considered as not applicable.

Consent for publication

We do not report any person-related or organisation-specific data but present a conceptual piece and therefore do not see it necessary to ask for consent for publication.

Competing interests

Dieckmann holds a professorship at the University of Stavanger, Norway, financed by an unconditional grant from the Laerdal Foundation to the University of Stavanger. Dieckmann leads the EuSim group, a group of simulation centres and experts, providing faculty development programmes. Qvindesland and Torgeirsen are faculty in EuSim courses. Thomas, Bushell, and Ersdal do not have any competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Collection of simulation scenario scripts.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dieckmann, P., Torgeirsen, K., Qvindesland, S.A. et al. The use of simulation to prepare and improve responses to infectious disease outbreaks like COVID-19: practical tips and resources from Norway, Denmark, and the UK. Adv Simul 5, 3 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-020-00121-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-020-00121-5