Abstract

Background

Undernutrition among under-five children is one of the intractable public health problems in Ethiopia. More recently, Ethiopia faced a rising problem of the double burden of malnutrition—where a mother may be overweight/obese, and a child is stated as having undernutrition (i.e., stunting, wasting, or underweight) under the same roof. The burden of double burden of malnutrition (DBM) and its association with maternal height are not yet fully understood in low-income countries including Ethiopia. The current analysis sought: (a) to determine the prevalence of double burden of malnutrition (i.e., overweight/obese mother paired with her child having one form of undernutrition) and (b) to examine the associations between the double burden of malnutrition and maternal height among mother–child pairs in Ethiopia.

Methods

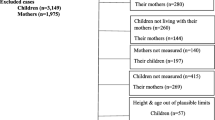

We used population-representative cross-sectional pooled data from four rounds of the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), conducted between 2000 and 2016. In our analysis, we included children aged 0–59 months born to mothers aged 15–49 years. A total of 33,454 mother–child pairs from four waves of EDHS were included in this study. The burden of DBM was the primary outcome, while the maternal stature was the exposure of interest. Anthropometric data were collected from children and their mothers. Height-for-age (HFA), weight-for-height (WFH), and weight-for-age (WFA) z-scores < − 2 SD were calculated and classified as stunted, wasting, and underweight, respectively. The association between the double burden of malnutrition and maternal stature was examined using hierarchical multilevel modeling.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of the double burden of malnutrition was 1.52% (95% CI 1.39–1.65). The prevalence of overweight/obese mothers and stunted children was 1.31% (95% CI 1.19–1.44), for overweight/obese mothers and wasted children, it was 0.23% (95% CI 0.18–0.28), and for overweight/obese mothers and underweight children, it was 0.58% (95% CI 0.51–0.66). Children whose mothers had tall stature (height ≥ 155.0 cm) were more likely to be in the double burden of malnutrition dyads than children whose mothers’ height ranged from 145 to 155 cm (AOR: 1.37, 95% CI 1.04–1.80). Similarly, the odds of the double burden of malnutrition was 2.98 times higher for children whose mothers had short stature (height < 145.0 cm) (AOR: 2.98, 95% CI 1.52–5.86) compared to those whose mothers had tall stature.

Conclusions

The overall prevalence of double burden of malnutrition among mother–child pairs in Ethiopia was less than 2%. Mothers with short stature were more likely to suffer from the double burden of malnutrition. As a result, nutrition interventions targeting households’ level double burden of malnutrition should focus on mothers with short stature to address the nutritional problem of mother and their children, which also has long-term and intergenerational benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coexistence of overweight and undernutrition among the members of a single household known as the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) has drawn more attention in recent years [1]. Undernutrition and overnutrition coexist simultaneously despite previously being understood and treated as separate public health problems [2, 3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the DBM is “characterized by the coexistence of undernutrition along with overnutrition (overweight and obesity), or diet-related non-communicable diseases, within individuals, households and populations, and across the life-course” [4]. At the household level, a double burden of malnutrition can exist—when a mother may be overweight/obese and a child has an undernutrition status (i.e., stunting, wasting, or underweight) [5].

Globally, around 45% of deaths among children under 5 years are linked to undernutrition [6]. It is also estimated that 149.2 million children under 5 suffered from stunting, while wasting affected 49 million children under the age of 5 in 2020 [6]. Evidence also showed that two out of five and more than one-quarter of all children suffering from stunting and wasting lived in Africa [6)]. Meanwhile, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the prevalence of overweight and obesity is rising rapidly, with adult women bearing the greatest burdens—ranging from 5.6 to 27.7% [7]. A recent study examining the trends of overweight and obesity among women in Africa showed statistically significant increasing trends in several SSA countries [8]. Furthermore, due to the rapid ongoing global nutrition transition, an increasing number of studies demonstrate that the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) is a particular challenge for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Although research is limited, sub-Saharan Africa has also been experiencing high levels of DBM in recent years [7, 18,19,20]. Earlier estimates on DBM in sub-Saharan Africa reported below 10% prevalence at the household level [21]. However, more recent studies have reported a high prevalence of DBM among mother–child pairs in SSA: overweight/obese mother–stunted child pairs, 13–20% in Kenya [22, 23], 10.3% in Nigeria [24], 14% in Egypt [21], and 1.8% to 23% in Ethiopia [11, 25, 26].

In Ethiopia, malnutrition affects women and children disproportionately [27, 28]. Overweight/obesity is rising rapidly while child undernutrition remains persistent. The prevalence of stunting, wasting, and being underweight were 37%, 21%, and 7%, respectively according to the 2019 Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey report [29]. Compared to the WHO cutoff values for the significance of undernutrition, the prevalence of stunting, wasting, and being underweight remained a serious public problem in the country [30].

Undernutrition has long been considered a major issue in Ethiopia; overweight and obesity have also been identified as growing problems [26, 31]. According to a recent study, 14.9% of women aged 15–49 years are overweight or obese, of which 83.3% were urban dwellers [32]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis also reported that the estimated pooled prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults in Ethiopia was 20.4% and 5.4%, respectively [33]. It has been noted that mothers’ overweight/obesity is associated with the nutrition transition situation [34], due to a shift in dietary patterns with populations in developing countries consuming more energy dense than before due to changes in economic conditions. This demonstrated that Ethiopia, like other LMICs, is subject to the inevitable consequences of DBM; however, the burden of DBM is still not fully understood [25, 26]. So far, a few studies on overweight and undernutrition coexisting at the household level have been reported [11, 25, 26, 35].

The DBM at the household level is a complex public health problem [36]. The most important contributing factors of DBM include the place of residence [24, 26], older age of the child (age ≥ 24 months) [25, 26, 37], being a female child [37], maternal older age (age over 30 years) [15, 37], household socioeconomic status [25, 38, 39], richest wealth quintile [15], average birth weight [25], maternal education [15, 37, 38], large family size/household size [11, 37], and more siblings in the household [38].

Maternal height is a useful indicator for predicting children’s risk of developing malnutrition [40,41,42,43,44]. However, its influences on DBM have not been well investigated. Only a few studies have shown that DBM is strongly tied to maternal height [15, 24, 37, 45, 46]. As mentioned, a few pocket studies from Mexico [47], Indonesia [37], Guatemala [45], and Brazil [48] have examined the associations and suggest that short maternal height is associated with a higher risk of DBM. Apart from these examples, studies on the association between maternal stature and DBM in developing countries are rare.

To our knowledge, no studies have documented such an association in Ethiopia. Also, there needs to be more data that have comprehensively examined household-level DBM using a large, pooled dataset in Ethiopia. Previous studies on DBM conducted in Ethiopia have focused on describing the individual-level DBM [35, 49,50,51], localized in some areas [11, 35], survey specific [25, 26], and focus on the coexistence of maternal overweight/obesity and child stunting or anemia [52]. Considering the above, the aims of the present study were to: (1) determine the prevalence of DBM and (2) examine the association between maternal stature and DBM among mother–child pairs in Ethiopia. Given the national and global targets of achieving food security and improving maternal and child nutrition, this study is paramount in providing factual insights regarding the current status of DBM and designing appropriate preventive strategies in Ethiopia. Additionally, with these pooled data, we better understand maternal stature's influence on the double burden of malnutrition.

Methods

Data sources and sampling design

This study utilized data from the four consecutive Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) (2000–2016), a nationally representative cross-sectional household survey [53,54,55,56]. Pooled data on mother–child pairs from the EDHS were included in the study, to explore the prevalence of double burden of malnutrition (DBM). This pooled data analysis also increased the study power, which allowed a full exploration of the effect of maternal height on DBM. In the EDHS, ever-married women aged 15–49 years were interviewed for data on women and children (0–59 months). The survey was designed to be representative at both national and regional levels. The EDHS sampling and household listing methods have been described elsewhere [56]. We used anthropometric indices such as height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age to evaluate children’s nutritional status below 5 years of age (0–59 months). In addition, the study used the women’s body mass index (BMI) according to WHO cutoff values [57]. Maternal body mass index (BMI) was classified as underweight (< 18.5 kg/ m2), normal (18.5 to < 24.99 kg/m2), or overweight/obesity ≥ 25.0 kg/m2).

The EDHS collected data on the nutritional status of children by measuring the weight and height of children under the age of 5 years in all sampled households, regardless of whether their mothers were interviewed in the survey or not. Weight was measured with an electronic mother–infant scale (SECA 878 flat) designed for mobile use [56]. Height was measured with a measuring board (ShorrBoard®). Children younger than 24 months were measured lying down on the board (recumbent length), while standing height was measured for all older children.

The three child anthropometric indices used in this study were calculated using growth standards published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2006 [58]. The height-for-age index is an indicator of linear growth retardation and cumulative growth deficits in children. Children with height-for-age Z-score below minus two standard deviations (− 2 SD) from the median of the WHO reference population are stunted or chronically malnourished. The weight-for-height index measures body mass in relation to body height or length and describes current nutritional status. Children whose Z-score is below minus two standard deviations (− 2 SD) from the median of the reference population are considered thin (wasted), or acutely undernourished. Weight-for-age is a composite index of height-for-age and weight-for-height that accounts for both acute and chronic undernutrition. Children whose weight-for-age Z-score is below minus two standard deviations (− 2 SD) from the median of the reference population are classified as underweight [58].

Outcome variable

The primary outcome of this study was DBM, derived from three child anthropometric indices (stunting, wasting, and underweight) and the body mass index (BMI) of their respective mothers. Height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-height (WHZ), and weight-for-age (WAZ) z-scores below − 2 SD of the WHO Child Growth Standard were used to define stunting, wasting, and underweight, respectively [58]. A child who was either stunted, wasted, or underweight and the mother is over-nourished (overweight/ obese) in the same household was considered as having DBM, as used in past studies [15, 25, 59]. Following previous studies, the binary response variable DBM was measured using “normal” and “DBM” response categories. Additionally, the prevalence of overweight/obese mothers and stunted children, overweight/obese mother and wasted children, and overweight/obese mother and underweight child was estimated.

Main exposure

The main exposure of our study was maternal height. We adopted height cutoffs used by previous studies [37, 60, 61], but subdivided them into three categories. Accordingly, we categorized maternal height as: very short (< 145.0 cm), short (145.0 to 154.9 cm) and normal/tall (≥ 155.0 cm).

Control variables

Covariates were considered based on the availability of data and previous literature [15, 25, 47, 62,63,64,65]. In this study, we included two levels of confounding variables: individual (i.e., child, maternal, and household factors) and community levels. The individual-level covariates included: child factors (child’s age in months, gender, birth order, birth interval, size of child at birth, diarrhea, fever, and ARI), maternal factors (mother’s age, mother’s education, mother's occupation, ANC visit, anemia status, listening to the radio, and watching television), and household-level covariates (wealth index, household size, type of cooking fuel, toilet facility, source of drinking water, household flooring, and time to get a water source). Lastly, the community-level factors include the place of residence (urban or rural) and contextual region of residence (agrarian, pastoralist, and city administration).

Data analysis

All analyses were carried out using STATA/MP version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The survey command (svy) in STATA was used to take into account the sampling design of the survey. Sampling weighting was applied to all descriptive statistics to compensate for the disproportionate allocation of the sample. The weighting technique is explained in full in the EDHS report [56]. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used to present the distribution of all variables.

Given the hierarchical nature of the EDHS data, a multilevel binary logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the association between DBM and maternal height. In this model-building process, we first performed an unadjusted bivariable multilevel analysis between DBM and exposure or each of the covariates. Variables in bivariable analysis with a p value < 0.2 were entered in the multilevel multivariable binary logistic regression models. All independent variables associated with the DBM were tested for multicollinearity and there was no evidence of multicollinearity. Following the recommendations of a previous study, five hierarchical models were run [66,67,68]. Accordingly, five models were fitted: the empty model without any explanatory variable was run to detect the presence of a possible contextual effect (Model I), Model II (Model I + child characteristics), Model III (Model II + mothers characteristics), Model IV (Model III + household characteristics), Model V (Model IV + community-level characteristics) were fitted. In our analysis, all models assumed a random intercept. Model comparisons were done using the deviance information criteria (DIC) and the model with the lowest DIC value was chosen as the best-fitted model for the data. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was computed for each model to show the amount of variations explained at each level of modeling. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p value < 0.05 in the Model V multivariable model were used to declare significant determinants of DBM and its association with maternal height. Finally, after controlling all covariates and exposure variables the mean value estimates were presented (the estimates are obtained after the post-estimation command) using the figure representing the predictive probability for DBM and maternal height.

Ethical consideration

The data used in this study were obtained from the MEASURE DHS Program, and permission for data access was obtained from the measure DHS program through an online request from http://www.dhsprogram.com. The data used for this study were publicly available with no personal identifier. There was no need for ethical clearance as the researcher did not interact with respondents.

Result

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 presents the frequency and the weighted distribution of DBM, overweight/obesity mother–stunted child, overweight/obesity mother–wasted child, overweight/obesity mother–underweight child, and covariates in the study population. In this study, we analyzed data from a total of 33,454 mother–child pairs among whom there were 20,417 (61.0%) normal/tall (≥ 155.0 cm) mothers, 12,265 (36.7%) short (145–155 cm) mothers, and 771 (2.3%) mothers were of very short (< 145.0 cm) stature. The mean maternal height was (156.69 cm ± 6.34). Almost 4 in 10 children belong to the age-group of 36–59 months. Most of the children resided in rural areas (89.2%).

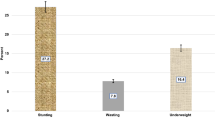

Prevalence of malnutrition

The prevalence of malnutrition is reported in Table 2. The prevalence of stunting, wasting, and being underweight among under-five children in Ethiopia is 47.31% (95% CI 46.77–47.84), 10.95% (95% CI 10.62–11.29), and 31.51% (95% CI 31.01–32.01), respectively. The prevalence of overweight/obese mothers was 3.21% (95% CI 3.03–3.40).

Prevalence of double burden of malnutrition

Table 2 also presents the weighted prevalence of different forms of the double burden of malnutrition. The prevalence of overweight/obesity mother and stunted children was 1.31% (95% CI 1.19–1.44), while the prevalence of overweight/obesity mother and the wasted child was 0.23% (95% CI 0.18–0.28) and that of overweight/obese mothers and the underweight children was 0.58% (95% CI 0.51–0.66). Overall, the prevalence of DBM was found to be 1.52% (95% CI 1.39–1.65). The prevalence of DBM was significantly higher (5.7%) among the children of women with very short maternal height (< 145 cm). The highest prevalence of the DBM (2.31%, 95% CI 1.95–2.72) occurred among children aged 24–35 months. DBM was highest among women over 35 years (2.54%, 95% CI 2.21–2.93) of age than women in any other age-group. The prevalence of DBM was higher among urban residents (4.74% vs 1.21%).

Association of DBM and maternal stature

The unadjusted association between DBM and exposure and other study covariates are given in Table 3. The association between DBM and maternal very short height (< 145 cm) was highly significant (p value < 0.001) in the unadjusted model. Tables 4 and 5 present the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% CI of DBM and maternal height. Our results showed that DBM was positively associated with maternal height adjusted for individual (i.e., child, maternal, household) and community-level covariates. The adjusted multilevel models estimated that compared to the children of tall mothers (height ≥ 155 cm), the odds of DBM was 1.37 times higher among children whose mothers’ height ranged from 145 to 155 cm (AOR: 1.37, 95% CI 1.04–1.80). The odds of DBM was 2.98 times higher among children whose mothers had short stature (height < 145 cm) (AOR: 2.98, 95% CI 1.52–5.86) compared to children whose mothers had tall stature (height ≥ 155 cm).

Table 5 summarizes unadjusted, adjusted odds ratios and absolute probability of DBM. Marginal effects show the change in probability when the predictor or independent variable increases by one unit. The change in probability of DBM when maternal height goes from normal to short increases by 2.2 percentage and is significant. Similarly, the change in probability when maternal height goes from short to very short increases by 4.6 percentage points, which is also significant.

Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities along with their 95% confidence interval. The predicted probability of DBM was on the “Y axis” and maternal height was on the “X axis.” The fitted line increases from right to left, indicating that as maternal height decreases from normal to very short, the probability of DBM increases.

Discussion

The concept of the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) at the household level is not well understood in Ethiopia. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive assessment undertaken: (a) to determine the prevalence of DBM and (b) to examine the associations between DBM and maternal height in Ethiopia. The prevalence of DBM was below 2%. Our results showed that DBM was strongly associated with maternal height after adjusting for potential individual and community-level covariates.

In this study, the overall prevalence of DBM was 1.52%. However, the DBM increased with age in women after 35 years and increased with urbanization. The current finding in India indicates a rising concern about DBM as the country goes through a perfect wave of changes in dietary patterns and physical activity due to urbanization and economic development [69]. Ethiopia is implementing policies that will allow the country to achieve lower-middle-income status. Henceforth, the coexistence of multiple forms of malnutrition in households will likely increase in the coming years. The double burden of malnutrition has also been linked to a high level of food insecurity and a higher prevalence of infection, combined with rapid population growth and urbanization, which may lead to an increase in the prevalence of DBM [19].

The existence of a double burden of malnutrition in the same household was reported in different low-income settings such as in Bangladesh [16, 70], Indonesia [37], Kenya [22], Nepal [15], and India [59]. Few studies have also reported Ethiopia's household-level double burden of malnutrition [11, 25, 26]. The observed prevalence of DBM was lower than the finding from a study in Nepal, 6.6% [15], and studies from Bangladesh, 6·3%, [70] and, 4.9%, [71]. The low-level prevalence of DBM might be due to the low proportion of women who are overweight or obese in the country. In Ethiopia, however, the proportion of women who are overweight or obese has increased over time from 3% in 2000 to 8% in 2016 [56]. In the same period, however, the prevalence of overweight/obesity increased from 6.5 to 22.1% between 2001 and 2016 among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) [72] in Nepal. In Bangladesh, the prevalence of overweight was about 29% and the rate of obesity was approximately 11% among women of reproductive age [73]. Another study from Bangladesh reported increases in the prevalence of overweight and obesity from 2004 to 2014 as follows: the prevalence of overweight increased from 11.4% in 2004 to 25.2% in 2014, and the prevalence of obesity increased from 3.5% to 11.2% over the same period of time [74]. The observed increase in mothers’ overweight or obesity was stated to be associated with the nutrition transition situation [34].

As documented in the current study, the prevalence of DBM is low in Ethiopia compared to other related low-income settings. Another possible explanation for this phenomenon relates to differences in the urbanization of society, maternal nutrition status, socioeconomic development, and sociocultural factors, which may lead to alterations in food consumption habits and accelerate the occurrence of DBM.

Prior evidence from 126 low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) revealed that the prevalence of household-level DBM ranged from 3 to 35%, with the most prevalent being maternal overweight/obesity and child stunting [2]. In our analysis, the prevalence of overweight/obese mother–stunted child pairs was 1.31%. The prevalence was closely comparable with a study finding from Nepal 1.54% [14]. However, our finding was much lower than the prevalence rates reported from Bangladesh at 4.10%, Pakistan at 3.93%, and Myanmar at 5.54% [14]. Additionally, a much higher prevalence of overweight/obese mother–stunted child was observed in Bangladesh at 24.5% [16], in Benin at 11.5% [75], and in Kenya at 20% [22]. Similarly, the prevalence of overweight/obese mothers and wasted or underweight children was lower than in related studies from Kenya [22] and Bangladesh [70]. The low prevalence of overweight/obese mothers with stunted children in Ethiopia could be attributed to the high burden of stunted children in rural areas and the high prevalence of maternal overweight/obesity in urban areas. According to the most recent 2019 Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey, childhood stunting remained stagnant at 37% (74.65% live in rural areas) and 12% of children under age 5 are severely stunted [29]. The majority of overweight or obese women are also found in urban areas, and the prevalence of overweight/obesity has increased significantly from 10.9% in 2000 to 21.4% in 2016 [31]. It is also worth noting that policy differences, as well as other commitments to combating malnutrition, as well as factors such as maternal nutrition status, socioeconomic development, and sociocultural factors, may account for variations in the prevalence of DBM.

It has already been reported that maternal stature is linked with adverse child and maternal health outcomes [44, 60, 61, 76,77,78,79]. Several studies have also examined the association of maternal height with child malnutrition [40, 42, 43, 80]. In our analysis, DBM was significantly associated with the mother’s height. The adjusted models estimated that compared to the children of tall mothers (height ≥ 155.0 cm), the odds of DBM significantly increased by about 1.37 times among the children of the mothers with 145.0 to 155.0 cm height. Similarly, the odds of DBM was 2.98 times higher for the children of the very shortest mothers (height < 145.0 cm) compared to the children of tall mothers (height ≥ 155.0 cm). This result is consistent with Sunuwar et al., finding in Nepal [15] which reported that short stature in mothers was strongly associated with the risk of DBM compared to mothers of normal height. These linkages also align with previous studies from Indonesia and Bangladesh [37], Mexico [47], Guatemala [81], and Brazil [48] reported that short maternal stature increases the risk of the double burden of malnutrition. Several factors and pathways may have contributed to and explained this association: (1) Body mass index (BMI) gain was significantly higher in short-statured women [82], (2) women of short stature are more likely to have undernourished children than women of normal stature [34, 76], (3) maternal height influences offspring linear growth over the growing period [42], (4) it has been also noted that women with short stature were more likely to suffer from chronic degenerative diseases and subsequently have stunted children than the women of normal stature [34], and (5) stunting is an intergenerational phenomenon passed down from mother to child and contributes to small for gestational age babies. As a result, being a very short or short mother may have carried one or more of the identified risks amplifying the likelihood of experiencing the DBM. This study highlights the importance of developing programs and policies that address the nutrition needs of short-statured mothers in order to break the vicious intergenerational cycle of malnutrition under the same roof.

The strength of this study lies in the robust analytical and statistical methods used. Our findings contribute significantly to knowledge by being the first to investigate the relationship between maternal stature and DBM in the Ethiopian context. Additionally, because we used a nationally representative dataset, the findings of this study are generalizable to similar low-income settings. Nonetheless, our study has some limitations, and the findings should be interpreted with caution. First, the nutritional status of the mother was assessed using BMI. BMI is less accurate than other methods such as waist–hip ratio and skinfold thickness methods to assess the type of overweight/obesity. Second, data on maternal overweight/obesity such as dietary intake, physical activity level, and health status were unavailable. Third, the study could not establish a causal pathway of the association between explanatory and dependent variables due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Fourth, because some of the independent variables were self-reported, there may have been some recall and social desirability bias, which is beyond the control of the current study. Finally, considering the skewed distribution of the DBM data findings should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Our study findings show a low prevalence of double burden of malnutrition among mother–child pairs in Ethiopia. Mothers with short and very short stature were more likely to suffer from the double burden of malnutrition. This link between short maternal height and DBM may imply that high-risk mothers (those who are short or very short in stature) should be prioritized for sufficient nutritious food supply and optimal nutrition to break the vicious cycle of malnutrition that exists under the same roof. Again, existing nutrition interventions must make significant and concerted efforts to combat the growing concern of DBM in Ethiopia.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available on the Measure DHS Web site https://dhsprogram.com after formal online registration and submission of the project title and detailed project description.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care visits

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DBM:

-

Double burden of malnutrition

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kosaka S, Umezaki M. A systematic review of the prevalence and predictors of the double burden of malnutrition within households. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(8):1118–27.

Popkin BM, Corvalan C, Grummer-Strawn LM. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10217):65–74.

Wells JC, Sawaya AL, Wibaek R, Mwangome M, Poullas MS, Yajnik CS, et al. The double burden of malnutrition: aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet. 2020;395(10217):75–88.

World Health Organization-double burden of malnutrition. Double burden of malnutrition [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 2]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/double-burden-malnutrition/en/.

Davis JN, Oaks BM, Engle-Stone R. The double burden of malnutrition: a systematic review of operational definitions. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(9):nzaa127.

UNICEF, WHO and the World Bank Group. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: key findings of the 2021 edition [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240025257.

Neupane S, Prakash KC, Doku DT. Overweight and obesity among women: analysis of demographic and health survey data from 32 Sub-Saharan African Countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;16(1):30.

Amugsi DA, Dimbuene ZT, Mberu B, Muthuri S, Ezeh AC. Prevalence and time trends in overweight and obesity among urban women: an analysis of demographic and health surveys data from 24 African countries, 1991–2014. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017344.

Pomati M, Mendoza-Quispe D, Anza-Ramirez C, Hernández-Vásquez A, Carrillo Larco RM, Fernandez G, et al. Trends and patterns of the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) in Peru: a pooled analysis of 129,159 mother–child dyads. Int J Obes. 2021;45(3):609–18.

Akombi BJ, Chitekwe S, Sahle BW, Renzaho AMN. Estimating the Double Burden of Malnutrition among 595,975 Children in 65 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Meta-Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 3];16(16). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/16/2886.

Bliznashka L, Blakstad MM, Berhane Y, Tadesse AW, Assefa N, Danaei G, et al. Household-level double burden of malnutrition in Ethiopia: a comparison of Addis Ababa and the rural district of Kersa. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(18):6354–68.

Wong CY, Zalilah MS, Chua EY, Norhasmah S, Chin YS, Siti Nur’Asyura A. Double-burden of malnutrition among the indigenous peoples (Orang Asli) of Peninsular Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):680.

Shinsugi C, Gunasekara D, Gunawardena NK, Subasinghe W, Miyoshi M, Kaneko S, et al. Double burden of maternal and child malnutrition and socioeconomic status in urban Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0224222.

Anik AI, Rahman MdM, Tareque MdI, Khan MdN, Alam MM. Double burden of malnutrition at household level: a comparative study among Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Myanmar. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221274.

Sunuwar DR, Singh DR, Pradhan PMS. Prevalence and factors associated with double and triple burden of malnutrition among mothers and children in Nepal: evidence from 2016 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Mamun S, Mascie-Taylor CGN. Double burden of malnutrition (DBM) and anaemia under the same roof: a Bangladesh perspective. Med Sci. 2019;7(2):20.

Hasan M, Sutradhar I, Shahabuddin A, Sarker M. Double burden of malnutrition among bangladeshi women: a literature review. Cureus [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/10222-double-burden-of-malnutrition-among-bangladeshi-women-a-literature-review.

Onyango AW, Jean-Baptiste J, Samburu B, Mahlangu TLM. Regional overview on the double burden of malnutrition and examples of program and policy responses: African region. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;75(2):127–30.

Wojcicki JM. The double burden household in sub-Saharan Africa: maternal overweight and obesity and childhood undernutrition from the year 2000: results from World Health Organization Data (WHO) and Demographic Health Surveys (DHS). BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1124.

Ahinkorah BO, Amadu I, Seidu AA, Okyere J, Duku E, Hagan JE, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with the triple burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients. 2021;13(6):2050.

Garrett J, Ruel MT. The coexistence of child undernutrition and maternal overweight: prevalence, hypotheses, and programme and policy implications. Matern Child Nutr. 2005;1(3):185–96.

Masibo PK, Humwa F, Macharia TN. The double burden of overnutrition and undernutrition in mother−child dyads in Kenya: demographic and health survey data, 2014. J Nutr Sci. 2020;9.

Fongar A, Gödecke T, Qaim M. Various forms of double burden of malnutrition problems exist in rural Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1543.

Senbanjo IO, Senbanjo CO, Afolabi WA, Olayiwola IO. Co-existence of maternal overweight and obesity with childhood undernutrition in rural and urban communities of Lagos State. Nigeria Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2019;90(3):266–74.

Tarekegn BT, Assimamaw NT, Atalell KA, Kassa SF, Muhye AB, Techane MA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of double and triple burden of malnutrition among child-mother pairs in Ethiopia: spatial and survey regression analysis. BMC Nutr. 2022;8(1):34.

Eshete T, Kumera G, Bazezew Y, Marie T, Alemu S, Shiferaw K. The coexistence of maternal overweight or obesity and child stunting in low-income country: Further data analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia demographic health survey (EDHS). Sci Afr. 2020;9:e00524.

Yeshaw Y, Kebede SA, Liyew AM, Tesema GA, Agegnehu CD, Teshale AB, et al. Determinants of overweight/obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia: multilevel analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e034963.

Sahiledengle B, Mwanri L, Petrucka P, Kumie A, Beressa G, Atlaw D, et al. Determinants of undernutrition among young children in Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20945.

EPHI and ICF. EPHI ICF. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2019: key indicators. Rockville: EPHI and ICF; 2019.

de Onis M, Borghi E, Arimond M, Webb P, Croft T, Saha K, et al. Prevalence thresholds for wasting, overweight and stunting in children under 5 years. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(1):175–9.

Ahmed KY, Abrha S, Page A, Arora A, Shiferaw S, Tadese F, et al. Trends and determinants of underweight and overweight/obesity among urban Ethiopian women from 2000 to 2016. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1276.

Mengesha Kassie A, Beletew Abate B, Wudu KM. Education and prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1189.

Kassie AM, Abate BB, Kassaw MW. Prevalence of overweight/obesity among the adult population in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e039200.

Ferreira HS, Moura FA, Cabral CR, Florêncio TMMT, Vieira RC, de Assunção ML. Short stature of mothers from an area endemic for undernutrition is associated with obesity, hypertension and stunted children: a population-based study in the semi-arid region of Alagoas. Northeast Brazil Br J Nutr. 2009;101(8):1239–45.

Sebsbie A, Minda A, Ahmed S. Co-existence of overweight/obesity and stunting: it’s prevalence and associated factors among under—five children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):377.

Guevara-Romero E, Flórez-García V, Egede LE, Yan A. Factors associated with the double burden of malnutrition at the household level: a scoping review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(25):6961–72.

Oddo VM, Rah JH, Semba RD, Sun K, Akhter N, Sari M, et al. Predictors of maternal and child double burden of malnutrition in rural Indonesia and Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(4):951–8.

Jehn M, Brewis A. Paradoxical malnutrition in mother–child pairs: Untangling the phenomenon of over- and under-nutrition in underdeveloped economies. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7(1):28–35.

Lee J, Houser RF, Must A, de Fulladolsa PP, Bermudez OI. Socioeconomic disparities and the familial coexistence of child stunting and maternal overweight in guatemala. Econ Hum Biol. 2012;10(3):232–41.

Karlsson O, Kim R, Bogin B, Subramanian S. Maternal height-standardized prevalence of stunting in 67 low- and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol. 2022;32(7):337–44.

Ali Z, Saaka M, Adams AG, Kamwininaang SK, Abizari AR. The effect of maternal and child factors on stunting, wasting and underweight among preschool children in Northern Ghana. BMC Nutr. 2017;3(1):31.

Addo OY, Stein AD, Fall CH, Gigante DP, Guntupalli AM, Horta BL, et al. Maternal height and child growth patterns. J Pediatr. 2013;163(2):549–54.

Varela-Silva MI, Azcorra H, Dickinson F, Bogin B, Frisancho AR. Influence of maternal stature, pregnancy age, and infant birth weight on growth during childhood in Yucatan, Mexico: a test of the intergenerational effects hypothesis. Am J Hum Biol. 2009;21(5):657–63.

Subramanian SV. Association of maternal height with child mortality, anthropometric failure, and anemia in India. JAMA. 2009;301(16):1691.

Lee J, Houser RF, Must A, de Fulladolsa PP, Bermudez OI. Disentangling nutritional factors and household characteristics related to child stunting and maternal overweight in Guatemala. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8(2):188–96.

Blankenship JL, Gwavuya S, Palaniappan U, Alfred J, de Brum F, Erasmus W. High double burden of child stunting and maternal overweight in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Matern Child Nutr [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Nov 8];16(S2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12832.

Félix-Beltrán L, Macinko J, Kuhn R. Maternal height and double-burden of malnutrition households in Mexico: stunted children with overweight or obese mothers. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(1):106–16.

Géa-Horta T, Silva RDCR, Fiaccone RL, Barreto ML, Velásquez-Meléndez G. Factors associated with nutritional outcomes in the mother–child dyad: a population-based cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(15):2725–33.

Amare HH, Lindtjorn B. Concurrent anemia and stunting among schoolchildren in Wonago district in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional multilevel analysis. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11158.

Farah AM, Nour TY, Endris BS, Gebreyesus SH. Concurrence of stunting and overweight/obesity among children: evidence from Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245456.

Roba AA, Assefa N, Dessie Y, Tolera A, Teji K, Elena H, et al. Prevalence and determinants of concurrent wasting and stunting and other indicators of malnutrition among children 6–59 months old in Kersa, Ethiopia. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(3):e13172.

Pradeilles R, Irache A, Norris T, Chitekwe S, Laillou A, Baye K. Magnitude, trends and drivers of the coexistence of maternal overweight/obesity and childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys (2005–2016). Matern Child Nutr [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 30]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13372.

EDHS. Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. 2001. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Authority and ORC Macro. 2000.

EDHS. Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Central Statistical Agency/Ethiopia and ORC Macro; 2006. 2005.

EDHS. Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Central Statistical Agency and ICF International; 2012. 2011.

EDHS. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF. 2016.

World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

WHO Child Growth Standards. Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. [Internet]; 2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924154693X.

Patel R, Srivastava S, Kumar P, Chauhan S. Factors associated with double burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India: a study based on National Family Health Survey 2015–16. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;1(116):105256.

Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group Small-for-Gestational-Age/Preterm Birth Working Group, Kozuki N, Katz J, Lee AC, Vogel JP, Silveira MF, et al. Short maternal stature increases risk of small-for-gestational-age and preterm births in low- and middle-income countries: individual participant data meta-analysis and population attributable fraction. J Nutr. 2015;145(11):2542–50.

Özaltin E. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1507.

Kumar P, Chauhan S, Patel R, Srivastava S, Bansod DW. Prevalence and factors associated with triple burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India: a study based on National Family Health Survey 2015–16. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):391.

Bates K, Gjonça A, Leone T. Double burden or double counting of child malnutrition? The methodological and theoretical implications of stuntingoverweight in low and middle income countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(8):779–85.

Determinants of stunting and overweight among young children and adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa—Susan Keino, Guy Plasqui, Grace Ettyang, Bart van den Borne; 2014 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Apr 26]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651403500203?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed.

Child stunting concurrent with wasting or being overweight: a 6-y follow up of a randomized maternal education trial in Uganda. 2021;3.

Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MT. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(1):224–7.

Ezeh OK, Abir T, Zainol NR, Al Mamun A, Milton AH, Haque MR, et al. Trends of stunting prevalence and its associated factors among nigerian children aged 0–59 months residing in the Northern Nigeria, 2008–2018. Nutrients. 2021;13(12):4312.

Garcia S, Sarmiento OL, Forde I, Velasco T. Socio-economic inequalities in malnutrition among children and adolescents in Colombia: the role of individual-, household- and community-level characteristics. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(9):1703–18.

Garrett JL, Ruel MT. Stunted child-overweight mother pairs: prevalence and association with economic development and urbanization. Food Nutr Bull. 2005;26(2):209–21.

Das S, Fahim SM, Islam MS, Biswas T, Mahfuz M, Ahmed T. Prevalence and sociodemographic determinants of household-level double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(8):1425–32.

Hauqe SE, Sakisaka K, Rahman M. Examining the relationship between socioeconomic status and the double burden of maternal over and child under-nutrition in Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(4):531–40.

Wei J, Bhurtyal A, Dhungana RR, Bhattarai B, Zheng J, Wang L, et al. Changes in patterns of the double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition in Nepal over time. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1321–34.

Hasan E, Khanam M, Shimul SN. Socio-economic inequalities in overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: a decomposition approach. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):263.

Biswas T, Uddin MdJ, Mamun AA, Pervin S, Garnett PS. Increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi women of reproductive age: findings from 2004 to 2014. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181080.

Dembélé B, Sossa Jérôme C, Saizonou J, Makoutodé PC, Mongbo Adé V, Guedègbé Capo-Chichi J, et al. Coexistence du surpoids ou obésité et retard de croissance dans les ménages du Sud-ouest Bénin. Santé Publique. 2018;30(1):115–24.

Gupta A, Cleland J, Sekher TV. Effects of parental stature on child stunting in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2022;54(4):605–16.

Marbaniang SP, Lhungdim H, Chaurasia H. Effect of maternal height on the risk of caesarean section in singleton births: evidence from a large-scale survey in India. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e054285.

Khatun W, Rasheed S, Alam A, Huda TM, Dibley MJ. Assessing the intergenerational linkage between short maternal stature and under-five stunting and wasting in Bangladesh. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1818.

Mogren I, Lindqvist M, Petersson K, Nilses C, Small R, Granåsen G, et al. Maternal height and risk of caesarean section in singleton births in Sweden—a population-based study using data from the Swedish Pregnancy Register 2011 to 2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198124.

Porwal A, Agarwal PK, Ashraf S, Acharya R, Ramesh S, Khan N, et al. Association of maternal height and body mass index with nutrition of children under 5 years of age in India: Evidence from Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016–18. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2021;30(4):675–86.

Doak CM, Campos Ponce M, Vossenaar M, Solomons NW. The stunted child with an overweight mother as a growing public health concern in resource-poor environments: a case study from Guatemala. Ann Hum Biol. 2016;43(2):122–30.

Sichieri R, Silva CVC, Moura AS. Combined effect of short stature and socioeconomic status on body mass index and weight gain during reproductive age in Brazilian women. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(10):1319–25.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Measure DHS Program for providing the DHS datasets.

Funding

No organization funded this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, and writing—original draft. LM contributed to visualization, validation, and writing—review and editing. KEA contributed to supervision, visualization, validation, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data were obtained via online registration to measure the DHS program and downloaded after the purpose of the analysis was communicated and approved. An approval letter for the use of the EDHS dataset was gained from MEASURE DHS. Because this study was based on secondary analysis of publicly available data with no personal identifier, no ethical considerations were needed before undertaking it. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahiledengle, B., Mwanri, L. & Agho, K.E. Association between maternal stature and household-level double burden of malnutrition: findings from a comprehensive analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. J Health Popul Nutr 42, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-023-00347-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-023-00347-9