Abstract

Background

This study assessed the interactions between income, nutritional status and intestinal parasitism in children in Brazil.

Methods

A cross-sectional study (n = 421 children aged 1 to 14 years living in the states of Piauí (rural communities in the city of Teresina) and Rio de Janeiro (rural and periurban communities in the city of Cachoeiras de Macacu) was performed in order to obtain income and anthropometric data, as well as fecal samples for parasitological analyses through the Ritchie technique.

Results

Children infected with Ascaris lumbricoides had significantly lower means of height-for-age z scores (− 1.36 ± 0.75 vs. − 0.11 ± 1.02; p < 0.001), weight-for-age z scores (− 1.23 ± 0.74 vs. 0.09 ± 1.15; p = 0.001), and weight-for-height z scores (− 0.68 ± 0.44 vs. 0.23 ± 1.25; p = 0.006) when compared with uninfected children. Infection with hookworm was also associated with lower means of height-for-age z scores (− 1.08 ± 1.17 vs. − 0.12 ± 1.02; p = 0.015) and weight-for-age z scores (− 1.03 ± 1.13 vs. 0.08 ± 1.15; p = 0.012). Children infected with Entamoeba coli presented significantly lower means of height-for-age z scores (− 0.54 ± 1.02 vs. − 0.09 ± 1.02; p = 0.005) and weight-for-age z scores (− 0.44 ± 1.15 vs. 0.12 ± 1.15; p = 0.002). The multivariate multiple linear regression analysis showed that height-for-age z scores are independently influenced by monthly per capita family income (β = 0.145; p = 0.003), female gender (β = 0.117; p = 0.015), and infections with A. lumbricoides (β = − 0.141; p = 0.006) and Entamoeba coli (β = − 0.100; p = 0.043). Weight-for-age z scores are influenced by monthly per capita family income (β = 0.175; p < 0.001), female gender (β = 0.123; p = 0.010), and infections with A. lumbricoides (β = − 0.127; p = 0.012), and Entamoeba coli (β = − 0.101; p = 0.039). Monthly per capita family income (β = 0.102; p = 0.039) and female gender (β = 0.134; p = 0.007) positively influences mid upper arm circumpherence.

Conclusions

Intestinal parasitism and low family income negatively influence the physical development of children in low-income communities in different Brazilian regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The first of the seventeen United Nations Sustainable Development Goals aims to reduce by at least half the proportion of people living in poverty by 2030. The second includes ending all forms of malnutrition, including meeting the internationally agreed targets for stunting and wasting in children under the age of five. The third goal includes ending epidemics of waterborne and neglected tropical diseases [1]. These three goals are interconnected and the dimensions they address—income, food and health—interact in a multi-causal feedback network.

In 1991, 67% of the Brazilian population lived in poverty (monthly per capita household income (MPCHI) less than half the Brazilian minimum wage) [2]. This proportion was reduced to 49% in 2000 and 34% in 2010. This year, large regional variation in the poverty rate was observed, with 56% in the Northeast, 53% in the North, 26% in the Central-West, 24% in the Southeast and 19% in the South [3]. More recent estimates show that the poverty rate fell from 26.5% in 2017 to 25.3% in 2018, still higher than in 2012 when the pre-recession rate was 22.8%. In addition, extreme poverty in Brazil last year reached its highest level since 2012, with 6.5% of the population—about 13.5 million people—with a monthly income below 40 USD [4].

The proportion of boys and girls aged 5–9 years with chronic malnutrition characterized by stunting (height deficit) was reduced respectively from 29.3% and 26.7% in 1975 to 7.2% and 6.3% in 2009 [5]. In parallel, the frequency of weight deficit in boys and girls aged 5–9 years dropped respectively from 5.7% and 5.4% to 4.3% and 3.9% in the same period [5]. The latest national-based survey also showed important regional differences, with higher prevalence rates of malnutrition in northern Brazil, lower rates in the South and similar rates close to the national average in the Northeast, Southeast and Central-West [5]. The specific mortality rate due to diarrheal disease in children under five years in Brazil was reduced from 22/100,000 children in 2000 to 5.5/100,000 in 2013. Regarding the regions, these rates in 2013 were 12.5 in the North, 8.3 in the Northeast, 6 in the Central-West, 2.3 in the Southeast and 2.1 in the South [6].

Soil-transmitted helminths (STHs), including Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworm (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale) and Trichuris trichiura, are notable for the potential severity of infection, which can cause intestinal obstruction (ascariasis), severe anemia (hookworm disease), and rectal prolapse and dysentery (trichuriasis) [1, 7]. Deficits in the physical and cognitive development of children are insidious and have chronic effects [8].

Despite the scarcity of country-based data on the burden of different soil-transmitted helminthiases (STHs) in Brazil, an analysis with mathematical modeling of secondary data estimates that the prevalence rates of ascariasis, hookworm infection and trichuriasis are 3.6%, 1.7% and 1.4% respectively, after scaling up of preventive chemoprophylaxis (mass drug administration (MDA)) and primary health care in the country [9]. However, in some rural and urban communities with poor sanitation and practicing open defecation, prevalence rates can be significantly higher [10,11,12,13]. Pathogenic species of protozoa inhabit the human digestive tract, including Giardia duodenalis and Entamoeba histolytica. These organisms are also associated with chronic nutrient spoliation and affect the physical and cognitive development of children [11, 14, 15]. G. duodenalis causes about 280 million symptomatic infections per year worldwide [16], and in low- and middle-income countries, the prevalence of giardiasis can reach up to 30% [17]. The transmission dynamics of giardiasis is complex, and it can be considered a zoonotic disease [17, 18]. It is estimated that amebiasis is associated with more than 55,000 deaths per year and that morbidity due to this parasite leads to the loss of 2.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [19].

There are no policies to control intestinal protozoan infections, and anti-STH MDA campaigns have made protozoa even more neglected [7, 8, 15]. In developing countries, this has influenced the etiologic profile of parasitic enteric infections towards a higher frequency of protozoa detection in coproparasitological surveys in recent decades [20,21,22]. The human intestine also hosts presumably non-pathogenic protozoans, such as Entamoeba coli, Endolimax nana, Iodamoeba butschlii, Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis [23]. Prevalence rates of infections with organisms such as Entamoeba coli have been considered indicators of environmental contamination with fecal matter in poor sanitation scenarios [21].

Regarding the impact of intestinal parasitism on the nutritional status of children, the literature presents conflicting results. This assessment is difficult due to the failure to consider an important confounding factor, family income, which may be very heterogeneous in some populations. According to the National Household Budget Survey [5], family income strongly influences the anthropometric parameters used to assess children's nutritional status in Brazil.

Objective

The study aim was to evaluate the interactions between income, nutritional status and intestinal parasitism in children living in periurban communities in two states in the Northeast and Southeast regions of Brazil.

Materials and methods

Description of the study areas and population

The study was carried out in August–September 2017 in the city of Teresina (TER) in the state of Piauí (Northeast macroregion) and from May 2017 to May 2019 in Cachoeiras de Macacu (CAM), in the state of Rio de Janeiro (Southeast macroregion) (see map in Fig. 1). In TER, two periurban communities with rural characteristics involved in the agrarian reform process (Camp 8 de Março and Settlement 17 de Maio) were studied, whose livelihood is obtained through family farming. In CAM, two urbanized districts (Papucaia and Ribeira) were studied, in addition to a community with rural characteristics (Marubaí). The communities studied in TER have a transitional tropical climate within the ecotonal zone called Mata de Cocais, which is situated in a transition zone between the Amazonian biomes (in the West), the Cerrado (in the South) and the Caatinga (in the East). In these communities, a high proportion of the population practice open defecation. In CAM, the areas studied have a tropical climate and are located in remnant areas of the Atlantic Forest, but with a high degree of deforestation for agriculture and livestock. The state of Rio de Janeiro has a higher Human Development Index (0.794) when compared to Piauí (0.690) [3].

Study design and statistical analyses

A community-based cross-sectional study was performed to obtain sociodemographic, anthropometric and parasitological data from 421 children living in TER (n = 70) and CAM (n = 351) (Fig. 2). All children aged 1 to 14 years old who lived in the studied communities were invited to participate in the study, and those who had chronic diseases were excluded due to the influence of baseline conditions on nutritional status. Sample sizes were not calculated, as we tried to include all children in the communities, to whom the pots for fecal collection were distributed. The rates of adherence and return of the fecal sample were approximately 50%, not significantly different between communities.

Body weight was recorded with a portable electronic scale, to the nearest 100 g. Children wore minimal clothing and were barefoot. Height was measured using an anthropometer to the nearest 0.1 cm. Z scores (standard deviation scores) of height for age (HAZ), weight for age (WAZ) and weight for height (WHZ) were assessed using the NutStat Module on EpiInfo 2000 version 3.2.2 using the CDC growth charts [24]. Stunting, underweight and wasting were defined by values equal or below − 2 for HAZ, WAZ and WHZ respectively. The mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) of the right arm was assessed with a flexible measuring tape, in the midpoint between the acromion and the olecranon processes. This study followed the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

After checked for normality, z score means of anthropometric parameters in children infected and uninfected with different parasites, living in distinct states and belonging to distinct genders were compared with Student's t tests. The correlation between the monthly per capita family income (MPCFI) of the families to which the children belonged and the anthropometric parameters was evaluated by simple linear regression. The rate of positivity for distinct parasites in distinct income groups was compared through the Fisher's exact test. Independent variables that significantly influenced anthropometric parameters were selected and multivariate analysis by multiple linear regression was performed in order to assess the influence of enteric parasitic infections on nutritional status, considering family income as the main confounding factor. In multiple linear regression, the z scores of the anthropometric indicators were considered dependent variables, and the variables selected in the bivariate analyses were tested to evaluate interactions, including gender and state. In all analyses, a p value of < 0.05 was used to establish statistical significance.

Laboratory procedures

Fecal samples were analyzed using the Ritchie technique [25] for the detection of helminth eggs and protozoan cysts. Briefly, 10% fecal suspensions were percolated in gauze and centrifuged (2500 rpm for 2 min). The supernatant was discarded, and 7 mL of distilled water, 3 mL of ethyl acetate and 1 drop of detergent were added. After further centrifugation and discarding of the supernatant, the pellet was analyzed by light microscopy [25].

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 421 children included in the study. The rates of chronic malnutrition (HAZ < − 2) in RJ and PI were 3.1% and 5.7%, respectively, the rates of low weight (WAZ < − 2) were 3.7% and 4.3%, and the rates of wasting (WHZ < − 2) were 11% and 0%, respectively. The prevalence rate of obesity (WAZ > 2) was 6.6% in RJ and 2.9% in PI. The proportion of children living in families with MPCHI < 45 USD (poverty) was 39.3% in RJ and 67% in PI.

Figure 3 shows the comparison of z score means of anthropometric parameters by state and gender. The WAZ mean was lower among children living in PI than in RJ (− 0.27 ± 1.06 vs. 0.13 ± 1.17; p = 0.008). The HAZ and WAZ means were lower among boys than among girls (− 0.26 ± 1.07 vs. 0.01 ± 0.96; p = 0.006, and − 0.08 ± 1.22 vs. 0.24 ± 1.18; p = 0.005, respectively).

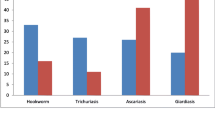

The comparison of means in children infected and uninfected by different parasites is represented in Fig. 4. Children infected with A. lumbricoides had significantly lower means of HAZ (− 1.36 ± 0.7 vs. − 0.11 ± 1.02; p < 0.001), WAZ (− 1.24 ± 0.75 vs. 0.09 ± 1.15; p = 0.001), and WHZ (− 0.68 ± 0.45 vs. 0.23 ± 1.26; p = 0.006) when compared to uninfected children. Infection with hookworm was also associated with lower means of HAZ (− 1.08 ± 1.17 vs. − 0.12 ± 1.02; p = 0.015) and WAZ (− 1.03 ± 1.13 vs. 0.08 ± 1.15; p = 0.012). Children infected with Entamoeba coli presented significantly lower means of HAZ (− 0.54 ± 1.01 vs. − 0.09 ± 1.02; p = 0.005) and WAZ (− 0.44 ± 1.15 vs. 0.12 ± 1.15; p = 0.002). No significant differences in nutritional status were found among children infected with E. histolytica / E. dispar or G. duodenalis.

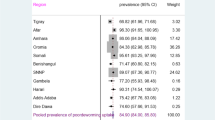

Table 2 presents the prevalence rates of infection by different intestinal parasites and other characteristics. Significantly higher positivity rates were observed in the state of Piauí when compared with Rio de Janeiro for A. lumbricoides (5.7% vs. 1.4%; p = 0.046), hookworm (8.6% vs. 0.3%; p < 0.001), Entamoeba coli (28.6% vs. 7.4%; p < 0.001) and Hymenolepis nana (2.9% vs. 0%; p = 0.027). Children belonging to families living in poverty (MPCHI < 45 USD) presented higher positivity rates for A. lumbricoides (3.8% vs. 0.8%; p = 0.047), Entamoeba coli (17.3% vs. 5.9%, p < 0.001) and G. duodenalis (15.1% vs. 6.4%, p = 0.004).

As shown in Table 3, the multivariate multiple linear regression analysis model showed that HAZ is independently influenced by MPCHI (β = 0.145; p = 0.003), female gender (β = 0.117; p = 0.015), and infections with A. lumbricoides (β = − 0.141; p = 0.006) and Entamoeba coli (β = − 0.100; p = 0.043). Similarly, WAZ is influenced by MPCHI (β = 0.175; p < 0.001), female gender (β = 0.123; p = 0.010), and infections with A. lumbricoides (β = − 0.127; p = 0.012) and Entamoeba coli (β = − 0.101; p = 0.039). MPCHI (β = 0.102; p = 0.039) and female gender (β = 0.134; p = 0.007) positively influences MUAC.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed some socioenvironmental variables affecting the nutritional status of children living in two periurban areas in Brazil, focusing on income and enteric infections. The main findings were the influence of MPCHI and infection with some species of intestinal parasites on the nutritional parameters evaluated. These findings reveal the vulnerability of children living in poverty in periurban communities in the states of Rio de Janeiro and Piauí.

Regarding income, many of the children studied live in families whose MPCHI is less than 40 USD per month, which defines extreme poverty in Brazil. The data suggest that raising family income through minimum income programs positively affects children's weight, height and arm circumference, by improving access to food. Higher family income positively influenced both the chronic malnutrition indicator HAZ as well as the nonspecific parameter WAZ, besides MUAC, demonstrating that the effects of economic poverty on nutritional status are felt in both short and long term.

Brazil substantially reduced the proportion of people living in poverty in recent years. The results of this study suggest the need to maintain income policies as a tool to fight poverty in a time of economic recession that challenges most social programs implemented in recent decades. In this context, the current recessive cycle of the Brazilian economy, associated with rising unemployment, austerity, and a reduction in family income, may currently be undermining the advances afforded by Brazil in reducing the rates of child malnutrition achieved in recent decades, and constituting an unfavorable framework for meeting 2030 agenda goals.

Despite the low prevalence of ascariasis presented by the communities, it was demonstrated that this infection significantly correlates with worse nutritional status of the children included in the research. Despite infection with A. lumbricoides being focally present in a few children—confirming the current trend of reducing the prevalence of STHs in Brazil—it affects negatively the anthropometric parameters studied.

Some studies have evaluated the influence of STHs on children's nutritional status in developing countries. In Sri Lanka, despite no relationship being found between the presence of ascariasis and undernutrition, infections with high parasite load were associated with decreased values of WHZ [26]. In Vietnam, ascariasis influenced negatively the serum concentration of vitamin A in an infection intensity dependent way [27]. In Kenya, STH in preschool children was associated with vitamin A and iron deficiency [28]. In northwestern Ethiopia, no association was found between intestinal helminthic infections and nutritional status [29]. Among Venezuelan Amerindians, enteric helminthic infections were significantly associated with lower HAZ and WHZ [30]. In Mexico, an association between ascariasis and malnutrition in economically poor communities was demonstrated [31]. In Cameroon, children infected with STHs had significantly lower HAZ averages, with infection by more than one species being even more deleterious [32]. Hookworm and A. lumbricoides were associated with lower values of HAZ, WAZ and WHZ in Nigeria [33, 34]. In Chad, there was an association between Hymenolepis nana infection and malnutrition [35]. In Brazil, stunting was associated with ascariasis infection among children and adolescents [36]. On the other hand, two studies in Brazil demonstrated that the only enteric parasite associated with lower values of anthropometric parameters was G. duodenalis [15, 37]. Taken together, these data demonstrate how intestinal parasitism is a factor guiding the possibilities for the full physical development of children in developing countries.

This study demonstrated that infection with Entamoeba coli also influences the evaluated anthropometric parameters. Entamoeba coli is considered a non-pathogenic protozoan that commensally inhabits the human intestinal tract. Nevertheless, some studies have explored the potential of Entamoeba coli to affect bowel function. Recently, it was demonstrated that Mexican children infected with Entamoeba coli or A. lumbricoides were more likely to have higher levels of stool leucocytes than uninfected children [38], pointing to the possibility of intestinal inflammatory activity triggered by these parasites. Entamoeba coli can also be considered a marker of inadequate sanitary conditions, denoting greater exposure to fecal pathogens. Thus, it could be interpreted that, in this study, Entamoeba coli-positive children would have a higher frequency of other intestinal infections that would influence their nutritional status. In Bolivia, it has been shown that children living in a poorer scenario have a higher prevalence rate of Entamoeba coli infection and have worse nutritional status [39].

Another finding of the study was the influence of gender on nutritional status, showing that males presented lower values of the nutritional parameters evaluated. The National Household Budget Survey conducted in 2008–2009 showed similar results, with higher frequencies of weight and height deficits among boys [5].

Data show the interaction between income, nutritional status and enteric parasitic infections in children living in periurban areas in two Brazilian capitals, one in the Northeast and one in the Southeast. The results point to the need to improve both the income of families living in poverty and the sanitation scenario in these communities, 10 years before the year 2030, which is the horizon for the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations.

Availability of data and materials

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Carvalho-Costa FA. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Abbreviations

- MPCHI:

-

Monthly per capita household income

- STHs:

-

Soil-transmitted helminthiases

- MDA:

-

Mass drug administration

- TER:

-

Teresina

- CAM:

-

Cachoeiras de Macacu

- HAZ:

-

Height for age

- WAZ:

-

Weight for age

- WHZ:

-

Weight for height

- MUAC:

-

Mid upper arm circumference

- MPCFI:

-

Monthly per capita family income

References

UN. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

BIRD. Brazil, a poverty assessment. 1995. http://r1.ufrrj.br/geac/portal/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/BIRD-Brazilpovertyassessment1995.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

Brasil-Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Censo Demográfico 2010 Características da população e dos domicílios Resultados do universo. 2010. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/93/cd_2010_caracteristicas_populacao_domicilios.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Síntese de Indicadores Sociais 2018. Uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. :2018 https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/media/com_mediaibge/arquivos/ce915924b20133cf3f9ec2d45c2542b0.pdf.

Brasil- Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008-2009. Antropometria e Estado Nutricional de Crianças, Adolescentes e Adultos no Brasil. 2010. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv45419.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

CEPI-DSS/ENSP/FIOCRUZ. Taxa de mortalidade específica por doenças diarreicas agudas em menores de 5 anos de idade, por ano, segundo região. 2016. http://dssbr.org/site/wpcontent/uploads/2016/08/Ind020202-20160610.pdf. Accessed in 02 Sept 2019.

Suthar PP, Doshi RP, Mehta C, Vadera KP. Incidental detection of ascariasis worms on USG in a protein energy malnourished (PEM) child with abdominal pain. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. https://doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-206668, 2015, mar12 1, bcr2014206668.

Blouin B, Casapia M, Joseph L, Gyorkos TW. A longitudinal cohort study of soil-transmitted helminth infections during the second year of life and associations with reduced long-term cognitive and verbal abilities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006688, 12, 7, e0006688.

Chammartin F, Guimarães LH, Scholte RG, Bavia ME, Utzinger J, Vounatsou P. Spatio-temporal distribution of soil-transmitted helminth infections in Brazil. Parasit Vectors. 2014. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-440, 7, 1, 440.

Monteiro KJL, Reis ERCD, Nunes BC, Jaeger LH, Calegar DA, Santos JPD et al. Focal persistence of soil-transmitted helminthiases in impoverished areas in the State of Piaui, Northeastern Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2018. https://doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-9946201860024.

Coronato-Nunes B, Calegar DA, Monteiro KJL, Hubert-Jaeger L, Reis ERC, Xavier SCDC, et al. Giardia intestinalis infection associated with malnutrition in children living in northeastern Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.8410.

Coronato Nunes B, Pavan MG, Jaeger LH, Monteiro KJ, Xavier SC, Monteiro FA, et al. Spatial and molecular epidemiology of Giardia intestinalis deep in the Amazon, Brazil. PLoS One. 2016. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158805, 11, 7, e0158805

Calegar DA, Nunes BC, Monteiro KJ, Santos JP, Toma HK, Gomes TF, et al. Frequency and molecular characterisation of Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, Entamoeba moshkovskii, and Entamoeba hartmanni in the context of water scarcity in northeastern Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760150383.

Mondal D, Petri WA Jr, Sack RB, Kirkpatrick BD, Haque R. Entamoeba histolytica-associated diarrheal illness is negatively associated with the growth of preschool children: evidence from a prospective study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006. https://doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.12.012, 100, 11, 1032, 1038.

Carvalho-Costa FA, Gonçalves AQ, Lassance SL, Silva Neto LM, Salmazo CA, Bóia MN. Giardia lamblia and other intestinal parasitic infections and their relationships with nutritional status in children in Brazilian Amazon. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652007000300003.

Ankarklev J, Jerlstrom-Hultqvist J, Ringqvist E, Troell K, Svard SG. Behind the smile: cell biology and disease mechanisms of Giardia species. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2317, 8, 6, 413, 422, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2317.

Coelho CH, Costa AO, Silva AC, Pucci MM, Serufo AV, Busatti HG, et al. Genotyping and descriptive proteomics of a potential zoonotic canine strain of Giardia duodenalis, infective to mice. PLoS One. 2016. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164946, 11, 10, e0164946

Feng Y, Xiao L. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00033-10.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095128.

Macchioni F, Segundo H, Gabrielli S, Totino V, Gonzales PR, Salazar E, et al. Dramatic decrease in prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and new insights into intestinal protozoa in children living in the Chaco region, Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0039.

Dias AP, Calegar D, Carvalho-Costa FA, Alencar MFL, Ignacio CF, da Silva MEC, et al. Assessing the influence of water management and rainfall seasonality on water quality and intestinal parasitism in rural Northeastern Brazil. J Trop Med. 2018. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8159354, 2018, 1, 10.

Periago MV, García R, Astudillo OG, Cabrera M, Abril MC. Prevalence of intestinal parasites and the absence of soil-transmitted helminths in Añatuya, Santiago del Estero, Argentina. Parasit Vectors. 2018. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3232-7, 11, 1, 638.

Peter J. Hotez. The other intestinal protozoa: enteric infections caused by Blastocystis hominis, Entamoeba coli, and Dientamoeba fragilis. Seminars in Pediatric Infections Diseases. 2000. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/pi.2000.6228, 11, 3, 178, 181.

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;246:1–190.

Young KH, Bullock SL, Melvin DM, Spruill CL. Ethyl acetate as a substitute for diethyl ether the formalin-ether sedimentation technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;10(6):852–3. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.10.6.852-853.1979.

Galgamuwa LS, Iddawela D, Dharmaratne SD. Prevalence and intensity of Ascaris lumbricoides infections in relation to undernutrition among children in a tea plantation community, Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2018. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-0984-3, 18, 1, 13.

de Gier B, Nga TT, Winichagoon P, Dijkhuizen MA, Khan NC, van de Bor M, et al. Species-specific associations between soil-transmitted helminths and micronutrients in Vietnamese schoolchildren. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0533.

Suchdev PS, Davis SM, Bartoces M, Ruth LJ, Worrell CM, Kanyi H et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infection and nutritional status among urban slum children in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.13-0560.

Verhagen LM, Incani RN, Franco CR, Ugarte A, Cadenas Y, Sierra Ruiz CI, Hermans PWM, Hoek D, Campos Ponce M, de Waard JH, Pinelli E High malnutrition rate in Venezuelan Yanomami compared to Warao Amerindians and Creoles: significant associations with intestinal parasites and anemia. PLoS One. 2013. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077581, 8, 10, e77581.

Gutierrez-Jimenez J, Torres-Sanchez MG, Fajardo-Martinez LP, Schlie-Guzman MA, Luna-Cazares LM, Gonzalez-Esquinca AR, et al. Malnutrition and the presence of intestinal parasites in children from the poorest municipalities of Mexico. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.2990.

Mbuh JV, Nembu NE. Malnutrition and intestinal helminth infections in schoolchildren from Dibanda, Cameroon. J Helminthol. 2013. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X12000016, 87, 1, 46, 51.

Oninla SO, Onayade AA, Owa JA. Impact of intestinal helminthiases on the nutritional status of primary-school children in Osun state, south-western Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2010. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1179/136485910X12851868779786, 104, 7, 583, 594.

Opara KN, Udoidung NI, Opara DC, Okon OE, Edosomwan EU, Udoh AJ. The impact of intestinal parasitic infections on the nutritional status of rural and urban school-aged children in Nigeria. Int J MCH AIDS. 2012;1(1):73–82. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.8.

Bechir M, Schelling E, Hamit MA, Tanner M, Zinsstag J. Parasitic infections, anemia and malnutrition among rural settled and mobile pastoralist mothers and their children in Chad. Ecohealth. 2012. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-011-0727-5.

Jardim-Botelho A, Brooker S, Geiger SM, Fleming F, Souza Lopes AC, Diemert DJ, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Bethony JM Age patterns in undernutrition and helminth infection in a rural area of Brazil: associations with ascariasis and hookworm. Trop Med Int Health. 2008.13, 4, 458, 467 https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02022.x.

Muniz-Junqueira MI, Queiroz EF. Relationship between protein-energy malnutrition, vitamin A, and parasitoses in living in Brasília. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002. https://doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/s0037-86822002000200002, 35, 2, 133, 142.

Zavala GA, García OP, Camacho M, Ronquillo D, Campos-Ponce M, Doak C, et al. Intestinal parasites: associations with intestinal and systemic inflammation. Parasite Immunol. 2018. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.

Terán G, Cuna W, Brañez F, Persson KEM, Rottenberg ME, Nylén S, et al. Differences in nutritional and health status in school children from the highlands and lowlands of Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0143

Abdi M, Nibret E, Munshea A. Prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and malnutrition among schoolchildren of the Zegie Peninsula, northwestern Ethiopia. J Infect Public Health. 2017. https://doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2016.02.009, 10, 1, 84, 92.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the professionals involved, in particular, communitarian health agents within the Family Health Strategy program of the municipality of Cachoeiras de Macacu—RJ/ Brazil.

Funding

This study was jointly supported by Foundation Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ) and Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: FAC, DAC. Formal analysis: FAC, DAC. Funding acquisition: FAC. Investigation: DAC, KJLM, ABG, PAB, JPdS, LHJ, BC. Project administration: FAC. Resources: FAC, MNB. Writing—original draft: FAC, DAC. Writing—review & editing: FAC, LHJ, BC. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (license CAAE 12125713.5.0000.5248) of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, Fiocruz. All subjects provided written informed consent, and the parent or legal guardian of all children included in this study provided written informed consent on their behalf.

Consent for publication

We hereby certify that in the above referred manuscript, all the data contained are accurate; all authors have participated in the work in a substantive way and are prepared to take public responsibility for the work; the manuscript has not been published, will not be published in total or in part, and is not being submitted for publication elsewhere.

Competing interests

The authors have no personal conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Calegar, D.A., Bacelar, P.A., Monteiro, K.J.L. et al. A community-based, cross-sectional study to assess interactions between income, nutritional status and enteric parasitism in two Brazilian cities: are we moving positively towards 2030?. J Health Popul Nutr 40, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-021-00252-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-021-00252-z