Abstract

The application of social sciences has been recognized as valuable to inclusive humanitarian programming that aims to be attentive to the needs and initiatives of affected communities. However, the integration of social science-informed community engagement (CE) approaches in humanitarian action remains episodic, fragmented, and under-resourced. This research article provides insights from a study that reviewed existing and needed capacities for the systematic integration of social sciences for community engagement in humanitarian action. We examined what capacity resources exist and what resources need to be developed for strengthening social science integration into humanitarian programming for improved engagement of affected and at-risk communities in conflict and hazard contexts. A mixed method approach was used, including twenty-two key informant interviews and a focus group discussion with social scientists and humanitarian practitioners, an online survey with 42 respondents, a literature review, and a year-long monthly consultation with social scientists and humanitarian practitioners in a UNICEF-led global technical working group. Results illustrate insights on the value of the “social science lens” in humanitarian action and current usage of different social science disciplines. Challenges found include different understandings (e.g., on standardization), languages and methods used by practitioners and social scientists, and how to integrate the seemingly “slow” processes of social sciences to fit emergency response. Institutional barriers to mainstream community-centered humanitarian action facilitated by the social sciences include top-down decision-making and resourcing, lack of localization, and many siloed, dispersed, and episodic efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Social sciences and community engagement in humanitarian action

Humanitarian crises are complicated situations in which hazards, conflicts, and/or epidemics are embedded in structural conditions of inequality that can make affected communitiesFootnote 1 more vulnerable (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman 2002). In these contexts, communities are often excluded from the design of humanitarian interventions and research, while outcomes prioritized by humanitarian organizations can miss the underlying structural issues causing or exacerbating humanitarian crises (Barnett 2021). Although guidelines and tools for community engagement emphasizing a partnership approach have proliferated in humanitarian projects since the late 1990s, attempts at engagement have often remained stuck in rhetoric and tokenism, replicating existing uneven power relations (Matenga et al. 2021; Hilhorst & Bankoff 2022). This highlights the need for community engagement in preparedness and response to ensure that community needs and voices are guiding inclusive humanitarian action and programming at the international, national, and local levels (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman 2002; United Nations 2005; Alexander 2015; Goldacre et al. 2015; Bardosh et al. 2019; Niederberger et al. 2018).

In a comprehensive report detailing the meaning of community engagement (CE), UNICEF has proposed the following understanding:

CE is an approach to directly involve local populations in all aspects of decision-making, implementation, and policy. Building on a participatory approach, CE can strengthen local capacities, community structures, and local ownership to improve transparency, accountability, and optimal resource allocations across diverse settings. When done well, CE improves the likelihood that communities lead on issues that affect them, access and use services, improve their well-being, and build resilience. CE expands the influence of local actors, facilitates the acceptance of information and public education and communication, and builds on existing local capacities. (UNICEF 2020: 6)

This understanding highlights the role of CE to empower communities and to foster accountability. It underwrites that community stakeholders should not be regarded as passive recipients of assistance but are holders of knowledge and expertise. If CE is a participatory process through which equitable partnerships are developed with community stakeholders, who are enabled to identify, develop, and implement community-led sustainable solutions to issues that are of concern to them, capacities should bolster a process that puts conditions in place for communities to be in charge. Beyond immediate humanitarian relief to support communities in urgent need, CE ideally also consists of co-creating longer-term opportunities for sustainable growth and fulfilling people’s potential, building resilience; promoting inclusive and sustainable growth; co-constructing effective governance and supporting the building of civil society worldwide by investing in people and their potential. And CE practices should “facilitate the accountability of humanitarian actors by facilitating and structuring ongoing communication on the appropriateness and effectiveness of initiatives.” (UNICEF 2020: 7).

The social sciences, such as anthropology, sociology, political sciences, social and organizational psychology, economics, and human geography, have an instrumental role to play in working towards this goal because critical, reflexive, and (often more) cultural constructivist examination of humanitarian crises and humanitarian programming is part of its core business. Many applied social scientists are trained to critically assess and also engage in practical problem solving (Nichter 2018; Janes and Corbett 2009). Social science methods, such as participatory action research or social network analysis, are useful tools to better understand the lived experiences of affected communities (Wilkinson et al. 2017; Le Marcis et al. 2019; Nichter 2018). Social science, for example through anthropology, political science, psychology, or legal analysis, can offer a deeper analysis of power dynamics, governance structures and processes, beliefs, norms, and behavioral attitudes in different contexts (Wilkinson et al. 2017; Le Marcis et al. 2019; Bardosh et al. 2020) And social science approaches have participatory methods to offer that can help to include and foreground community voices in decision-making, map community-relevant needs and figure out how to address them in ways that are beneficial and constructive to communities, which can be conducive to the systematic integration of affected communities in humanitarian processes and promoting their inclusion across all levels of humanitarian decision making (Batniji et al. 2006; Stellmach et al. 2018). Social science approaches can be used broadly in the humanitarian field to increase equitable, inclusive governance, facilitate mutual benefit among community, humanitarian, and academic partners, and promote reciprocal knowledge translation, incorporating community theories into the research, making humanitarian programming not only more just but also more effective (Wallerstein 2008; Pratt 2020).

Lack of integration

Based on these observations, we would expect that CE informed by social science approaches, methods, evidence, and skills would result in more holistic and effective action and programming. The social sciences can facilitate the processes necessary to disrupt the unequal power relations embedded in the humanitarian system, which have an impact on the way humanitarian aid, preparedness, response, and recovery is carried out and who it benefits how (Matenga et al. 2021; Nichter 2018; Niederberger et al. 2018). We hypothesize that the use of social science for CE supports this transformational process in at least four ways: (1) by critically analyzing the origins and mechanisms of humanitarian crises and interventions, providing a nuanced understanding, including of master narratives and flows of money; (2) by challenging dominant framings of crises and what needs to be done by whom through producing contextualized knowledge together with rather than about communities, thereby offering alternative perspectives and insights; (3) highlighting narratives that acknowledge the responsibility and accountability of the involved actors and explore new possibilities for working together (Nichter 2018; Pratt et al. 2020); and (4) set a scientific standard for the humanitarian system to enhancing opportunities for community stakeholders to build solutions to community challenges, develop research questions and set priorities, collaborate on data collection and analysis, and implement practical strategies for addressing inequities (London 2005; Pratt 2020).

However, while CE efforts have a long history in humanitarian programming, technical, methodological, and operational grounding of CE in science methods and approaches is not at all widespread (Ashworth et al. 2021; Satizábal et al. 2022). There have been recent efforts to improve this situation, with greater emphasis on preparedness, long-term planning, and a deeper focus on the role of social science in a “people-centered” approach that aims to build trust and long-term relations with crisis-affected populations (Delgado 2021; Sphere 2018; UNICEF 2020; WHO Health Cluster 2017). Such an approach includes looking beyond the immediate emergency towards opportunities for longer-term livelihood reconstruction and sustainable development, recovery, and preparedness (Dempsey and Munslow 2009). In practice, this would mean continuous interaction, appropriate consultation, and shared decision-making with diverse community groups, acting on their concerns in a timely manner, and building in channels that allow for feedback and support accountability of different authorities and actors on changes made (OCHA 2015; Panther-Brick 2022). There are some careful signs of a shared political commitment to joint humanitarian decision-making with affected as well as “at-risk” communities, at least in theory, with CE included in the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Transformative agenda (2017), Core Humanitarian Standard (2014) and Sphere Handbook (2018). As the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) describes it, CE “implies a more pro-active process that should align with all responses’ programming, distinct from conventional public information and advocacy” (2015: 1). Through various disciplines, social science approaches could help populations strengthen their voice in addressing their needs, and provide tools to community stakeholders, humanitarian practitioners, consultants or policy makers to better integrate communities in the preparation, response or recovery from humanitarian crises (Duncan 2014; Gibbs et al. 2013; Laverack and Manoncourt 2016).

To some extent, social science research is already applied to address some of the outstanding issues and to answer open questions in the context of humanitarian crises. In the last decade, the application of social sciences has grown and the value of methodologies and insights acquired from empirical social research has been increasingly acknowledged as essential in addressing humanitarian crises (Gibbs et al. 2013; Laverack and Manoncourt 2016; Tembo 2021). This has been especially the case for public health emergencies (PHE), with social sciences, notably anthropology, sociology, and health psychology, being credited for playing a crucial role in CE in recent epidemics and disease outbreaks, including by powerful humanitarian and public health institutions (Stellmach et al. 2018; WHO 2018; Abramowitz et al. 2018; Bardosh et al. 2020; Giles-Vernick et al. 2019; Tembo 2021). Efforts to include social science approaches and insights have especially been focused on PHE as the West-African Ebola outbreak (Le Marcis et al. 2019; Richards 2016; Richardson et al. 2016) and COVID-19 (Carter et al. 2020; Osborne et al. 2021) instilled a growing awareness of the need for integral approaches that consider the social, cultural, political and behavioral dimensions of infectious disease outbreaks. Yet, even in PHE, the use of social science knowledge, tools and approaches has not been systematic (Ashworth et al. 2021; Bardosh et al. 2020; Carter et al. 2020; Giles-Vernick et al. 2019).

A recent literature review focusing on hazards and conflict settings showed there is no established and standardized use of social sciences to benefit CE and encourage more holistic humanitarian programming (Toro-Alzate et al. 2023). The review shows that only a small minority of peer-reviewed publications in the humanitarian field of disasters and conflicts—18 out of 1093, and 4 out of 315 Gy literature reports—tangibly comment on the relevance of social sciences, mostly only in passing and implicitly. Furthermore, CE is mostly seen as instrumental involvement, for example, to collect data in emergency situations and receive feedback on interventions, but not as an integral part of a transformative intervention. As the review concludes, there is a knowledge and implementation gap in relation to social science to strengthen and mainstream CE across all humanitarian contexts, and especially that of disasters and conflicts (2023:1). Overall, across the humanitarian field, practitioners and social scientists both observe a consistent gap between the ideas and promise of social science integration into CE, and the actual practice on the ground, which often remains ad hoc and unsystematic (Toro-Alzate et al. 2023). How, then, to better integrate the social sciences in community engagement in humanitarian action?

This study draws specific insights from a project that explored existing and needed capacities for the systematic integration of social sciences for community engagement in humanitarian action (SS4CE).Footnote 2 The overall project was led by the UNICEF Social and Behavioral Change team (SBC) with the support of USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, and implemented from October 2020 to December 2022. It consisted of two phases. In the first phase, the UNICEF SBC team had carried out a global consultation on the needs for community-centered humanitarian programming, resulting in a set of global humanitarian goods identified and prioritized by humanitarian practitioners and social scientists worldwide. In the second phase, the project included a consultation, mapping, and literature review that was carried out collectively with global partners through a working group structure but led and carried out by a team of researchers affiliated to the Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development (AIGHD) in close collaboration with the UNICEF SBC team. The objective was to learn about gaps and needs in integral, participatory, and effective humanitarian response and how social science methods and skills can be used to include and strengthen community-centered (and community-led) approaches. While humanitarian programming in general was considered, the particular focus in the project was on conflicts and hazards contexts, including but not limited to disasters. This paper specifically uses the insights based on the second phase.

Paper aim and structure

Based on our review of literature, we theorize that building SS4CE capacity does not only mean to use the social sciences to better understand community dynamics and facilitate action on the ground, but also to transform uneven power relations and institutional humanitarianism. Using the UNICEF definition of CE as a starting point, the aim of this paper is to describe the perceived merits of the social science approach as reported by practitioners and social scientists working in the humanitarian field, and to review operational, technical and structural challenges to systematic integration of social sciences in community engagement based on our sample. The results are organized into three main themes, each with their own subthemes: (1) what the social sciences can contribute to CE in humanitarian action, (2) operational and technical challenges to the integration of social sciences in CE, and (3) structural challenges described to the integration of social sciences in CE including a reflection on the positioning of this research study itself.

Methods

Research infrastructure

The study was conducted from December 2021 through December 2022. The research team consisted of one senior, one mid-level, and four junior social science researchers affiliated with the Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development (AIGHD), one mid-level social science researcher affiliated with the Institute Pasteur’s Ecology and Anthropology of Emerging Diseases Unit, and three senior humanitarian practitioners affiliated with UNICEF’s Social and Behavioral Change Unit. Weekly meetings were established with members of this core team during the entire course of 2022 and into early 2023. In addition, the research team was in ongoing dialogue with twenty-five members of a monthly technical working group, which consisted of humanitarian practitioners and social scientists of seven UN/intergovernmental agencies, four international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), and ten academic institutes. Technical working group members discussed the research design, provided input for the specific activities such as the training mapping and the survey, and advised based on what they saw as the most important issues related to social sciences and CE capacity development in the humanitarian field. The insights emerging from the collected data were presented and discussed in the technical working group meetings. Products based on the research findings, such as a project report and a competency framework for those using the social sciences to engage communities in humanitarian action, were discussed and adapted in accordance with input from technical working group members. The technical working group was also involved in a co-creative process to formulate the recommendations to facilitate capacity development to integrate social science approaches and insights in community engagement across humanitarian networks and organizations.

Data collection and analysis

A mixed method approach was used. First, eighteen semi-structured interviews were carried out with participants involved in CE primarily as social scientists working in an academic environment (n = 6), primarily as humanitarian practitioners (n = 6), and as professionals who worked on CE both in an academic and humanitarian environment (n = 6). Nine participants identified as working for a UN/intergovernmental agency, six in academia, and three in INGOs. Participants worked at different organizational levels in humanitarian action. Recruitment was conducted through the technical working group and through direct contacts of the study team. All interviews were conducted over Microsoft Teams and lasted approximately 1 h. The interviews were recorded and transcribed and then coded in a team coding exercise with the qualitative data analysis software Dedoose. Each transcript went through a first round of coding by one team member and a second round of coding by another team member. Codes were discussed within the team on a weekly basis. Additionally, four interviews were conducted with social scientists and professionals from civil society organizations in Colombia. These interviews followed a different format, taking a more reflexive approach towards CE and humanitarian action from the perspective of community-based actors in the Global South. As these interviews were conducted in Spanish, transcription was done manually, and coding done separately.

Second, a 24-question online survey was developed to obtain insights from a larger group of social scientists and humanitarian practitioners regarding their experiences in the application of social sciences for community engagement in humanitarian action. The survey consisted of closed and open-ended questions covering the respondents’ training, their experience with and needs for SS4CE integration, and priority themes such as localization and decolonization. The survey was disseminated using the online survey tool Qualtrics XM and was open for response from mid-May 2022 until the end of June 2022. The survey was distributed among the SS4CE Strategic Advisory Group, the technical working group members, the Sonar-Global network,Footnote 3 and the Network on Humanitarian Action (NOHA).Footnote 4 Participants were asked to distribute the survey within their respective networks and organizations. The quantitative data analysis involved collecting, collating, and counting all anonymous responses to the survey. The data was primarily analyzed descriptively using SPSS + . Because respondent selection for this survey was not random and people self-selected to participate, the results cannot be generalized beyond the sample. The data does however provide indications of possible trends to be confirmed in further studies. Of the 42 survey respondents, more than 85% had direct, practical experience with community engagement in humanitarian action. Respondents had working experience in all regions of the world, with 60% of the survey respondents being stationed in the Global South. The respondents had experience in many different fields and positions in humanitarian action, with almost 40% identifying themselves as a social science researcher and 44% as a frontline worker, program manager, or humanitarian practitioner.

Third, at a later stage, a focus group discussion was held with community-based civil society organizations working in humanitarian contexts. The focus group discussion was organized together with the Network for Empowered Aid Response (NEAR),Footnote 5 a national coalition of humanitarian, development, and resilience actors in India. Seven Indian civil society organizations participated. All of them worked with communities in disaster-vulnerable or affected areas, particularly prone to flooding, cyclones, and droughts. As local actors with a key role in and for communities in humanitarian contexts, their perspectives on community engagement and using the social sciences in programming were valuable to capture experiences and inputs from community-based organizations on the ground.

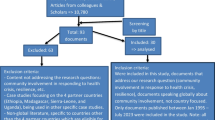

Parallel to these research activities, the project team conducted an online mapping of existing trainings that include social science approaches for community engagement in humanitarian action. Through a comprehensive internet-based search as well as examination of trainings suggested by participants in the interviews, survey, and technical working group meetings, the researchers sought out available courses, workshops, seminars, manuals, as well as individuals, organizations, networks, and initiatives that could contribute resources. Mapping was done for trainings in English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, and Dutch. Relevance was determined based on the presence of social science approaches, community engagement, and humanitarian, conflict, disaster, and/or hazard in the title and training description. A set of indicators determined in dialogue with the technical working group members was used to assess relevance and quality of the components. An XLS database of training resources was developed based on the results of the mapping.

Ethical considerations

Considering the nature of the research topic, the participants, and the intended use of the research, the project was determined as not requiring a comprehensive ethical review process by the Amsterdam Medical Center’s medical ethical review board (AMC METC, W22_074 # 22.107). Nevertheless, the researchers in the team adhered to research quality and ethical standards common to social science research (European Commission 2021). The researchers followed guidelines for data collection, storage, and sharing laid out in a project data management plan. This data management plan ensured all the collected data in the project was processed and stored in a secure, orderly, and uniform fashion. At the beginning of the interviews and focus group discussion, informed consent was obtained from participants for their participation in the research project, as well as for being recorded and having their contributions anonymously stored on the secure project server. Participants were made aware they could retract their participation at any time or request statements would be off-the-record, also in retrospect, and relevant passages of the recording and corresponding sections in the transcript would be deleted. In the survey introduction participants were informed they could discontinue the survey at any time.

Limitations

The study was embedded in a larger strategic trajectory initiated by UNICEF to mainstream the use of social science approaches in humanitarian programming with the objective to further strengthen community-centered and community-led humanitarian action. The SS4CE project aimed to explore how humanitarian action on the ground could be made more inclusive and effective with social science approaches, but also to understand how higher (management) levels of international agencies and (Northern) donors could shift to structurally different ways of programming. To support this process, it was important to have partners on board from different organizations and across the humanitarian field. The technical working group that was central to the project included specific expert humanitarians and social scientists based at different humanitarian agencies and NGOs, to foster a network while building upon earlier activities carried out to integrate social science into CE and humanitarian programming, as well as providing strategic recommendations on the accountability of the humanitarian institutions and relevant organizational change processes. Most technical working group members were from or based in the Global North, and active at higher management and programming levels of humanitarian programming and research. Actors in the Global North and in middle and higher management levels were seen as well-positioned to push the standard on community-based and -led humanitarian programming informed by social science.

The project’s organization was defined by this trajectory. As researchers coming to a project embedded in the structure of international agencies—even as it had been guided by an ambition to change that very structure—that had already run its first phase and had been conceptualized without us, we were limited in the design of the research. Guided by the strategic agenda, space, and funding within which the project operated, its focus and design did not initially include reaching out to community actors: the deliberate choice had been to first focus on the system’s structural challenges from within, and stakeholders envisioned in this project were actors operating within the system and particularly in global institutions.

However, believing that all actors need to be involved in these processes, also those that focus on what are framed as “internal” challenges in the sector, the research team advocated for more inclusion of social science scholars, humanitarian practitioners, and community actors from the Global South throughout the project in order to have the process of change be nourished by different insights. Insights from Global South actors and community-based actors on how social science approaches could foster inclusive CE not only were an important inclusion to perspectives on disciplinary and methodological contributions but also had the potential to spur the decolonizing and accountability processes in the humanitarian system itself, especially regarding some of the structural challenges of the institutions that hold accountability to design programs and interventions that are people-centered. To address the limited perspective of community-based actors, we proposed to add to the interviews with members of the technical working group—of which four members were based in the Global South—additional interviews with humanitarian professionals or social scientists from the Global South, specifically in Colombia. Furthermore, we added to the project design a focus group discussion with community-based civil society organizations working in humanitarian contexts in India, and we distributed the survey more widely. Thus social science scholars and humanitarian practitioners from the Global South were included in the study, both in the survey and the interviews and through the technical working group that we worked with, and we included community actors through the focus group discussion with civil society organizations in India and the interviews with community-based actors in Colombia. This remained far from the long-term collaborative community-centered processes we would have liked to see in an initiative to change such a key process of humanitarian programming and structures, especially one aimed at stimulating participatory and community-centered processes. But within the restrained structure of the project, the greater inclusion of actors from the Global South and community-based workers were important inclusions to talk to community actors and send a critical signal to the programming levels within humanitarian management and funding structures.

This context illustrates the complexities and difficulties at hand. The project exposed the limitations of the system to even consider the social sciences and their application within the accountability mechanisms of the system in order to ensure community-centered and community-led programming. Yet, we believed it provided an opportunity for further advocacy and leveraging insights regarding existing and needed SS4CE capacities to influence structural change in humanitarian systems and architecture. We do not think that efforts to make humanitarianism less top-down and less dominated by Global North actors should be dismissed just because they are led by northern actors. They can use their capital to bolster these humanitarian programming restructuring efforts. Nonetheless, the processes should be collaboratively steered and include partners from the Global North and South, community actors, humanitarian practitioners, and social scientists.

In further SS4CE efforts, we strongly suggest, from the conceptualization onwards, to include more perspectives from communities and from actors working directly with communities in the Global South, specifically in the potential steps to operationalize and use the guidance and tools that have been developed within institutional actions of the multiple humanitarian actors—aid organizations or academic within the humanitarian system.

Results

We present our findings along two lines of inquiry and their respective recommendations: (1) what the social sciences can contribute to CE in humanitarian action and (2) the main needs and gaps that hinder a systematic integration of the social sciences. The needs and gaps are categorized into two categories. The first category includes needs and gaps of an operational or technical nature, relating to (the training, exchange, and transfer of) skills, tools, language, and knowledge. The second category refers to needs and gaps of a structural kind, relating to the systemic conditions that can hinder or facilitate the use of social science for inclusive, accountable, and effective humanitarian action, planning, response, and preparedness to ensure communities’ wellbeing and resilience to crises in the long-term. Together, these findings provide insights into what capacity development could focus on, and how and to whom it should be offered (with what aim).

What the social sciences can contribute to CE in humanitarian action

This section presents an overview of the contributions the social sciences can make to meaningful, effective CE in humanitarian action. Participants mentioned a comprehensive list of skills, perspectives, methods, and approaches they find especially important and suggest should be learned by humanitarian practitioners. These are listed in the columns in Fig. 1 below.

The table provides an overview of the contributions, skills, techniques, and methods that research participants identified as useful to enhance CE. Some of the competencies participants mentioned, such as reflexivity and sensitivity, might not be exclusive to the social sciences, but do result from (critical) social science training. Participants mentioned that many social science skills and methods are not necessarily clear-cut and teachable, but rather rely on personal dispositions, soft skills, or, as one participant put it, “human skills,” such as empathy and establishing rapport. Communication skills, for instance, could be part of a training or course, but empathy is not something that is teachable. It can be, however, part of a combined attitude and outlook that increases sensitivity, empathy, reflexivity, and critical understanding, benefitting the methods that can help identify community needs and how they can be addressed.

The social science lens in HA

Participants described sensitivity, empathy, and communication skills as specific values that social science approaches can contribute to CE. Along with these values, social scientists are said to hold a critical understanding of a broader cultural, economic, and sociopolitical context that participants referred to as “the social science lens”:

I think often the social science approach allows people to think a bit more critically around these things, like who we will be engaging with? How are we engaging with them? What are the risks? What are the unintended consequences if we do this? What might happen further? And a lot more. I don’t know how you call it, but sort of bigger picture thinking than often happens, typically, within a kind of operational mindset, and I say that not in any way to discredit the operational mindset, because probably as purely social scientists we might never get anything done. But yeah, I think that’s a real benefit. (Social scientist, INGO)

The interviewed social scientists, especially, pointed to a combination of technical and analytical skills and methodologies, which together with the “social science lens” bring attentiveness to social relations and variation helps to understand contexts and connect with communities. This social science lens is the basis of engaging with communities, understanding their needs, and supporting them in meaningful, inclusive, and effective responses and preparedness and recovery. It can infuse humanitarian practitioners with a conscious awareness of their position and help create a bridge between communities and (international) humanitarian organizations. It stimulates the input and uptake of community perspectives. At the same time, the above statement also illustrates a tension between the perceived critical, pensative, and reflective social scientists who might be slowed down by their constant contemplating and weighing of options versus the practitioner who acts without too critical of a stance. This dissonance between two perceived modes of operation does not only touch upon the tension between action and reflection, but also on matters of speed, which will be discussed further below.

Participants’ responses emphasize that soft skills and competencies are as important in applying SS4CE in humanitarian action as more technical skills and techniques. Soft or interpersonal skills are often mentioned as bringing social scientists “closer to people.” These skills include empathy, patience, being able to work in a team, being able to build trust and rapport, being able to “really” or “actively” listen to people. Sometimes such person-driven approaches are also more about attitudes, which are often personality-dependentFootnote 6 but might be shaped by the moral focus, reflexivity, and attentiveness and sensitivity to power dynamics that form part of training in the social sciences. They are essential elements contributing to the “social science lens” or “social mind.”

One social scientist working in an INGO described how the spectrum of types of social science work applied in humanitarian programming has broadened since she started in her position. Initially, requests for social science support had a focus on the technical use of qualitative methods, as they were articulated around operational problems and the answers usually were in the format of research, but social science approaches have become more broadly applied:

My role started as a qualitative method implementer and then gradually opened up to broader social science views, incorporating broader perspectives on social science essentially. So, if there was something going on that people didn’t understand and suspect it might be a cultural problem, and then did a study essentially to understand what the problem was… I think that’s evolved a lot over time in terms of moments where social scientists are involved. They are the problem-solving parties there, in terms of assessments [and] evaluative work. And that has expanded beyond research to programmatic assessment. …So not purely in a kind of data collection, but more in terms of programmatic support around community related activities. (Social scientist, INGO)

Participants attributed to the social sciences numerous and important technical contributions that methodologically ensure that communities are taken seriously, including co-constructive and participatory methodologies. Indeed, technical skills for data collection and analysis in qualitative research methods have been the starting point for social science approaches in humanitarian contexts. The combination of technical, analytical skills, and interpersonal skills have provided visible added value of social scientists when engaging with communities as well as in programmatic assessment, evaluation, and planning. That combination is also where some of SS4CE’s transformational power lies—in changing the outlook on community engagement through a critical and empowering stance that can identify and call out inequalities and injustices. Participants noted an inherent respect by social scientists of community knowledge and their own position in relationship to this knowledge. This is part of a reflexiveness and positionality dominant in, for example, anthropological approaches, but it is also intrinsic to a critical approach to humanitarianism and the power relations of Global North and South. Social scientists tend to be trained to take a critical stance and make efforts to put structures in place that ensure communities (e.g., in the Global South) can take care of themselves, that recognize and integrate local knowledge and community resources to design adequate and sustainable strategies and long-term resilience, as well as help put in place interventions that are accountable to affected communities without paternalism. Without making light of the barriers social scientists, humanitarians and communities can face in the decolonization of the humanitarian field, the social lens and critical outlook provide the qualities needed to accommodate steps towards collective and community-centered action.

Usage of different social science disciplines

The social science disciplines participants mentioned most frequently as beneficial to apply in community engagement in humanitarian contexts were anthropology and sociology. These were followed by psychology, communication sciences, history, political science, and geography. Law and economic disciplines were least mentioned, but some survey respondents mentioned these. This could also be represented by a bias of the profiles of social scientists that are currently engaged most in this sector, as well as the scope of the partners in this initiative. There were, however, differences between how beneficial the different disciplines were perceived to be, depending on respondent roles. This was especially significant in the survey responses. When looking at social science disciplines mentioned as beneficial in CE in humanitarian action depending on the respondent’s roles (see Fig. 2 below), political science and pedagogy are seen as beneficial mostly by social science researchers. On the other hand, no social science researcher mentioned law as beneficial. Humanitarian practitioners on the other hand find journalism, law, economics, and communication science most beneficial, while frontline workers emphasize law, history, and geography. Finally, program managers indicated law and journalism are most useful in CE work.

Anthropology is seen as the “key to understand needs and priorities” (Social scientist/HP, INGO). Anthropology, especially through ethnography, and psychology were seen as helpful in telling different stories of conflict and their consequences, including individual trauma and community impact. Such stories are always diverse, but they show how communities are affected by crises. While we are not arguing that all humanitarian practitioners should learn the methods through which these stories are told, it is key to make the value of these stories understood to practitioners, management, and donors. The power of these stories as “results” lies with their form of experiential summaries that can be easily understood and leveraged by humanitarian practitioners, donors, and policy makers for effective communication and advocacy, as well as informing adaptive programs and actions.

Operational and technical challenges to integrating social sciences in CE

As the findings described above show, the social sciences can unearth complex insights into the needs of communities, and contribute to CE approaches in humanitarian action that are attentive, critical, and rely on trust- and bridge-building. However, several challenges impede these insights and approaches from being used when designing and implementing humanitarian assistance, building up in the recovery phase, or preparing for crises to come. An ongoing challenge is the different understandings of context that exist between social scientists and humanitarian practitioners, but also between different humanitarian agencies.

Different understandings, language, and methods

Social scientists in academia and humanitarian practitioners appear to have quite different understandings of core social science concepts, to the point that one participant noted a need for translation: “To make sure social science finds its way into humanitarian practice, we first need to understand each other.” (Social scientist, academia). Humanitarian practitioners find social science language difficult to understand. Jargon is problematic because it is a barrier to translation into action. Both groups appear to use different languages and methods depending on the institutional contexts and the original aims these are grounded in. While social scientists tend to focus on comprehensive knowledge production (“research for knowledge”), for humanitarian practitioners the emphasis lies on immediate action (“research for interventions”). Collected information primarily serves that action, and particularly in time-pressed crises this information needs to be “fit for purpose”, or “good enough”. Good enough here means good and reliable, collected through scientifically sound methods, but the time for collecting and analyzing data needs to be short and results packaged in easily digestible and applicable chunks.

To systematically integrate SS4CE in humanitarian action, it is key for academically based social scientists to understand humanitarian programming and operations to be able to effectively collect needed information for humanitarian programs. This includes understanding the roles of different institutional actors, but also the protocols and Humanitarian Program Cycle (HPC) (OCHA 2023) that frame how the humanitarian architecture functions and what actors and resources are needed at specific stages. Another point that participants made repeatedly is that even in cases where social sciences have been used in humanitarian action or in studies, valuable insights that were gained would still have benefitted from further translation for humanitarian application. Humanitarian practitioners pointed out that when applied studies are done, these are often done by agencies who are not operational, and this maintains “the gap between the academic research domain” and the operational world. To link social science insights to operational action, research evidence needs to be better translated into explicit actionable points to inform decisions in action and policy.

Humanitarians, on the other hand, could benefit from understanding key language, concepts, and approaches used in the social sciences, and what they can do with these. Many practitioners seem to have limited notions of what social science can bring—often restricted to health communication—or how they can really use it to inform their interventions, beyond a legitimizing veneer that can be used to claim “culture”—seen as a static social category—has been accounted for. Another issue is that while humanitarian practitioners might already use social science principles and tools, they do not always refer to them as such or ground them in social science theories or methodologies. This is not to say that some agencies and community-based organizations have not made strides to integrate social science perspectives and approaches. Some organizations have dedicated teams or programs consisting of social scientists and humanitarian practitioners that actively explore how to marry the different understandings and operating modus. These multidisciplinary teams can be challenging, but also valuable spaces for exchange. Such cases illustrate the importance of promoting shared transdisciplinary spaces where different areas of expertise come together. Multidisciplinary teams can function as a bridge, translator and provide fertile ground for knowledge exchange and commonly developed frameworks to facilitate a common understanding.

Using social science in time-sensitive humanitarian action and programming

Ideally, evidence must be both high quality and “fit for purpose” to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of humanitarian interventions. Participants noted, however, that social scientists tend to get stuck in their contributions because of the impression that longitudinal research and slow science alone render “good” data. Good CE relies on understanding context, building trust, and sustainable (working) relationships in, and with, communities. Understanding such context as part of social science research can take years. Consequently, for many social scientists, the rapid collection and reporting of data may jeopardize the robustness of their information. They fear to leave things out or not get it exactly right. Not coincidentally, seen from the humanitarian perspective, social sciences are often perceived as slow and requiring intensive and longitudinal research engagement. Anthropology and sociology, the social sciences that were mentioned by participants as the most relevant to engage communities, are seen as traditionally associated with immersive fieldwork, ethnography, observation, and participation.

Despite these views, there are plenty of social scientists, including some of the interview participants and technical working group members, who apply rapid research methods for data collection and analysis in anthropology and sociology, such as rapid appraisal techniques, interviewing, social network mapping of social and political dynamics, participatory action research, and evidence summaries to answer pressing questions in a health and humanitarian emergency. As participants pointed out, some guidelines for this rapid research exist (Vindrola-Padros & Johnson 2020). It was also noted that it can be extremely helpful to build operational social science needs around a network of other social scientists who pre-exist in a particular setting that one can connect to, to hit the ground running. Still, despite such rapid solutions, an obvious tension remains: while action during a crisis needs to be rapid, dedication to a crisis throughout its cycle—including long-term recovery and preparedness for possible future contingencies, as well as funding—needs to be longitudinal.

Standardization

This entire issue is also reflected in the different attitudes between humanitarian practitioners and more academic social scientists on standardization. As one social scientist working in a humanitarian agency noted: “We’re not standardized, we’re not systematized. We’re not simplified. So then for humanitarians, we’re not useful.” (Social scientist, UN/intergovernmental agency). Academia-based social scientists tended to speak out against standardization, as it may utilize the social sciences to provide a sense of legitimacy to imposing a fixed framework on individual contexts. Instead, they argued that social sciences should help to provide context-sensitive interpretations that refine, adapt, or challenge standardized approaches offered by global or international agencies and donors. Remaining independent of the processes of global networks remains an important precondition for such a critical attitude. Humanitarian practitioners on the other hand see standardization as a systematic integration of social science approaches in SOPs or protocols, budgeting, and programming that are important to track progress as well as measure accountability at different moments and interventions. They maintained that to this end, the systemic mainstreaming of SS4CE is necessary, as is the consolidation of different procedures across the humanitarian landscape. However, they clarified that this “standardization in approaches and processes” acknowledges that the application will be contextualized (Humanitarian practitioners, UN/intergovernmental agency). A humanitarian practitioner stated that as standardization is an “intrinsic characteristic of humanitarian action” which facilitates quick responses, it is key that social scientists understand these standards, to know what information is relevant in humanitarian programming and responses: “If social scientists know which concrete actions need to take place, always, in the case of, for example, a flood scenario, they can think about the social factors that need to be considered when implementing a response, and how they can provide evidence to ensure the engagement of affected communities in support of humanitarian processes.” (Humanitarian practitioner, INGO). Humanitarian practitioners also warned that standardization brings risks of maintaining untenable bureaucratic standards imposed by donors in the Global North to transfer financial resources; these untenable standards “must end” rather than shifting to local institutions and governance.

Structural challenges to integrating social sciences in CE

Many of the challenges impeding the systematic integration of SS4CE in humanitarian action are rooted in issues of structure, power inequalities, and the way the humanitarian and international health fields are organized. These structures define the hierarchy of who sets the agenda, who carries it out, under what conditions, and who is impacted by it. A guiding principle of humanitarianism is to strive for neutrality. While its actors are purported to be neutral, this often is in tension with the political and social nature of humanitarian action. Participants agreed that they first and foremost need to be community advocates, building bridges between communities and humanitarian actors: “You should be able to negotiate in the name of people, not taking their voice, but act like the bridge. This is the application of social sciences connected with CE” (Colombian practitioner, local NGO). However, while supporting empowerment and decolonization is important, other actors and structures need to support and enable this. A number of structural barriers to this, however, were expressed. These included (1) top-down decision-making and resourcing, (2) lack of actual participation of communities in localized and decolonized efforts, and (3) siloed, dispersed, and episodic efforts. Overall, addressing this requires a systemic shift in humanitarianism and development.

Top-down decision-making and resourcing

Hiring practices guide the composition of teams and have a great effect on the expertise present within and of the team, the dialogue taking place, and the approaches that this opens up. While this cannot be generalized, it is clear that while multidisciplinary teams illustrate the value of social sciences for CE in humanitarian action, work still needs to be done, at the top, to hand over some control to communities or local actors and to allow more time and funding for activities that might not always render immediate, measurable results. To stimulate donors and management, as well as hiring managers, towards more inclusive and multidisciplinary practices, it is vital they understand the contributions that SS4CE and participatory community-led practices can bring. Donors and management, who have control over funding and (the most) decision-making power, however, do not always appear to fully understand the value of social science or even CE. As one participant put it, there is a “reluctance from donors to fund a CE approach, and an even higher reluctance to do so when local actors are applying for funding” (Humanitarian practitioner, INGO). Often, indicators used to measure the success of projects do not capture the effects of CE because these are longer-term impacts. As budgets are tied to projects, investments in overarching infrastructure such as capacity are often not possible. Trainings that are developed might then not reach their audience. An SS4CE advocacy culture, in which contributions of the social science and CE in humanitarian action are made explicit and their wider inclusion or mainstreaming is encouraged, can help donors and high-level management understand what is required.

Localization, decolonization, and the participation of communities

To promote inclusive and effective humanitarian action, participants expressed that it is essential to reflect on how humanitarian and social science practices can be affected by colonial legacies and perpetuate inequities and focus on dismantling those practices. While CE was perceived by survey respondents as well implemented from an instrumental perspective, it was not recognized by survey and interview participants as a transformative activity leading to localization. Furthermore, while community inclusion in social science research occurs in data collection and analysis, it still needs to improve in research design and dissemination. Communities are often not included in grant proposal writing, and even if donors ask for community actors to be included, this can often become more tokenistic than significant influencing the conditions of projects, the design, and the questions asked. In addition, funding agencies have expressed worries that community leaders may be partisan, not representing all community members (Humanitarian professional, INGO). Local power structures should also not be discounted; as one of the participants said: “Don’t confuse Southern leaders with local ownership.” (Social scientist, university). For the sustained engagement of local actors, the support of international organizations, in terms of resources (i.e., funding) and capacity strengthening, was highlighted as essential to “institutionalize localization”. For participants, institutionalizing localization requires collaborative efforts to create change across different actors in the humanitarian landscape, including through partnerships with community actors and local government.

To work in equitable partnership with community stakeholders, participants say communities need to be involved in decision-making processes that impact on their well-being and ability for response and recovery to link genuine and respectful partnerships to aspirations for self-determination of vulnerable communities. They also need to be in control of the data that gets collected with the aim to benefit them. As a social scientist working in a UN/intergovernmental agency noted: “surveys tend to be prioritized because you can do them quicker, potentially cheaper. That information then is taken externally and analyzed, and it’s much less likely to be used by the persons who are local” (Social scientist, UN/intergovernmental agency). To prevent data from getting extracted and funneled off for use by intervening actors from the North while not being made available to local communities, some humanitarian agencies have started implementing community ethical review boards. This is an operational layer that stimulates accountability and builds capacity in communities. Participants noted that elements which seemingly very few agencies are concerned with are the usage and development of data by local communities within their own knowledge traditions (and what these could contribute to humanitarian action), as well as efforts to incorporate community perspectives of what humanitarian organizations should be holding themselves accountable to. This could help to regard community stakeholders as holders of knowledge and expertise rather than passive recipients of aid, an important step in the structural changing process to decolonize humanitarian action.

Siloed, dispersed, and episodic efforts

Participants expressed a lack of integration, coordination, and sustained commitment to CE and capacity development for CE in humanitarian action. There are several examples of multiple and/or parallel efforts in data collection and training. At the same time, there is a lack of oversight and participants worry that each independent effort to collect social science information only provides a partial picture depending on areas of expertise, organizational mandates, and thematic clusters. The lack of follow-up occurs when it comes to the use of capacity development tools. With trainings, efforts are often not sustained. This lack of follow-up is also signaled to harm relationships with communities, who are tired of researchers coming in, collecting their data, and never hearing from them again after data collection is over. Research and action entailing the design, implementation, and reporting of research during, after, and in preparation of emergencies and disasters is rare. The effectiveness of CE interventions is not measured, for lack of tools, time, and/or intention, especially in the case of interventions with a project-focused, temporal character. Our analysis found that connecting and coordinating efforts, as well as following up on efforts and building on existing activities and structures, was seen among many respondents to be fundamental for knowledge generation and capacity strengthening. Another imperative is following up with research and even avoiding research unless there is a plan to respond to findings and to avoid false expectations—relying on the principle of “do no harm” and building relationships of trust with communities. Returning data to the communities and closing the loop need to be guiding principles to ensure continuity and avoid extractive practices. The systematic integration of collaborative and participatory research methodologies such as participatory action research (PAR) and community-based participatory research (CPBR), which have already been used in humanitarian contexts (see for example Harper and Gubrium 2017), could offer a response to such shortcomings. This will boost CE’s potential to redistribute power. It would tilt the scale towards more co-productive processes, although great care should be taken to ensure equity in co-production and make participation among all community members accessible. This should allow the inclusion of communities from initial phases such as the research design. Within emergency responses, collaborative action can be achieved by setting up rapid response community panels, strengthening existing community relationships, and developing contingency plans for alternative methods of engagement (Tembo 2021). By expanding current practice and recognizing the fundamental change in programming culture that is required, senior management and other staff within humanitarian organizations, as well as donors, can do much to raise the profile and demonstrate the effect of social science-informed co-production. As one of the participants said, they can do this by recommending or mandating collaborative social science research and developing mechanisms to make funding directly available to civil sector organizations without impeding conditions (Humanitarian professional, INGO). The particiant went on to say that funders, humanitarian practitioners, and researchers also need to ensure that research priorities are determined with or by communities and that a wide range of community members are involved throughout the research process.

SS4CE to support power shifts in humanitarianism and development

Finally, general critiques were expressed concerning the role of humanitarianism and the tasks that it might maintain. Many of these tasks could be solved by local actors taking up roles themselves. In addition, in many crisis contexts, there is a view that humanitarian agencies have been encroaching into the sphere of long-term or ongoing engagement, forming a structural presence. Yet, while such connection is needed for long-term CE, humanitarian organizations do not collaborate on structural local efforts as they are guided by core humanitarian principles such as neutrality and impartiality, while development actors are considered partners with longer-term engagements with national governments and other local actors (see also O’Dempsey and Munslow 2009). This is a conundrum in need of addressing. Participants further note that there is little investment in how CE can boost preparedness. One of the most important things that needs to happen for inclusive, localized SS4CE is a shift in power and responsibility to local actors responding to, and planning for, humanitarian crises. A shift in thinking is needed towards sustainable, resilient and locally based systems in which international (humanitarian) organizations would play a supporting role. As one social scientist noted: “humanitarian organizations need to phase themselves out.” Capacity development needs to focus on making external actors—humanitarian practitioners, social scientists from the Global North—obsolete. Some humanitarian actors have committed to this process, as the need signaled by the UNICEF SBC and the departure point of this project shows. They can be powerful partners in this process towards community-led and locally-based preparedness and development. However, as the positionality of this study within a larger project illustrates, there is a real risk that international organizations remain leaders in these processes rather than shift to become partners in a supporting role. Efforts to set up structural conditions for communities to be in charge of humanitarian preparedness, response, and recovery are still defined and led by international organizations. The project in which we conducted our study was, ironically so, no exception. Global North, high-level actors steered a process to explore and employ the uses of social science in the transition to a more locally based, community-led humanitarian system. This happened even though the project was actually examining the structural challenges of the institutions that hold accountability to design programs and interventions that are people-centered. It illustrates the very complexities, challenges, and also ironies at work of the problem at hand. The process underlying the study was an effort to decolonize humanitarian work and undo some of the dominant institutional cultures and unequal power structures as seen through a process mostly driven from the global networks, rather than through a co-created and/or through bottom-up mechanisms. Indeed if we are considering longer-term decolonization efforts this project also highlights a gap in the accountability of these systems. It shows all the more how difficult and urgent this topic is and how much work there is to be done to make collaborative, community-centered programming happen. Care should be taken to hold international humanitarian organizations accountable to inclusive community-centered programming and action, even as they ostentatiously aim to redress institutional conditions and power imbalances, the logic, and structures. So, while a project such as SS4CE can help to enable this shift more quickly and committedly, the research described here should be followed up with new community-based social science research in humanitarian contexts in local contexts. We invite other researchers and humanitarian practitioners at all levels—but especially at the top where a shift is paramount—and communities to join in this process.

Conclusion

This paper presents findings on the value of social science to community engagement and identifies a number of challenges that need to be tackled to advance further integration of social sciences in community engagement in the humanitarian contexts of hazards and conflicts. We used a mixed method approach, including twenty-two key informant interviews and a focus group discussion with social scientists and humanitarian practitioners, an online survey, a literature review, and a year-long monthly consultation with social scientists and humanitarian practitioners in a UNICEF-led global technical working group. These different methodologies and perspectives of participants helped us to understand the needs from key stakeholders in the field, such as practitioners working on different levels of the humanitarian system and social scientists, as well as the practitioners’ perspectives about the challenges to further integration.

We find that a SS4CE agenda has some unique benefits. SS4CE can be a bridge between practitioners, researchers, and communities. The social science lens can help contextualize interventions, and bring researchers closer to people by “really listening”. Trust is key for working relationships to benefit all sides involved, in which partners co-create together as equals and avoid false expectations. When going beyond the ticking of boxes, integration of social science methods and tools in community engagement can lead to a more reflexive and attuned humanitarian practice in which the experiences, conditions, and needs of local partners are better integrated.Footnote 7 These findings confirm previous work done on the potentiality of the contribution of the social sciences (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman 2002; United Nations 2005; Hilhorst & Bankoff 2022; Alexander 2015; Goldacre et al. 2015; Bardosh et al. 2019; Niederberger et al. 2018). At the same time, they also confirm that the social sciences have not yet been able to set scientific standards in this field (London 2005; Pratt 2020). To further integration in this field, reflection on humanitarian practices and the relationships between researchers and practitioners as well as the power dynamics in the system overall is highlighted. Our findings report what is often left unsaid in the academic literature: social scientists are generally seen as too theoretical, too slow, and not practical enough by humanitarian practitioners. Humanitarian practitioners also find social science language and reporting difficult to understand. On the other hand, standardization in humanitarian action is observed with suspicion by social scientists, and the data are often insufficiently scrutinized from a long-term perspective.

While these tensions exist, the larger structural challenges mentioned emphasize the need for humanitarian agencies and donors to buy in and commit to a power shift in which localization, decolonization, de-siloing, and capacity building become principled goals. Ironically, this is also illustrated by the limitations to the research design of this study itself, which was positioned in this dynamic and unable to fully engage the community at all needed levels, providing largely “a view from the top.” But quick fixes are unlikely to solve a deep historical problem. All actors need to be committed to what will be a long-term, at times uncomfortable, but also a hopeful process. This study is but one small step in that process, which overall will require an overhaul not only of the way humanitarian programs, projects, and studies are designed, but also of how they are carried out, who decides their content, and what outcomes it brings for whom. Imagining alternative ways of doing research and applying it in practice and intervention is a long process, in which we also a learn by doing (Freire 1982). We invite humanitarian scholars, and practitioners and social scientists to reflect on the sector’s and disciplines’ responsibilities in the face of this process and help us in thinking about ways forward. SS4CE needs to be enabled and allowed to inform and strengthen a form of response, recovery, and preparedness in humanitarian programming that puts communities in the lead through collaborative efforts which will radically affect structural conditions that affect how humanitarian crises unfold. This project has been a modest step in that direction, we now call on humanitarian actors, social scientists, and communities to move forward.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Notes

In this paper, we define “community” broadly to encompass policy makers, local leaders, community organizations, health providers, affected and at-risk individuals, their families, and other community members.

The products of the project, such as a mapping and set of common principles of ethics and data sharing, a code of conduct mapping as well as a mapping of capacity needs for SS4CE, a competency framework and compendium of case studies can be found here: https://www.sbcguidance.org/understand/social-science-community-engagement-humanitarian-action

Sonar-Global is a network of researchers and practitioners that bolsters the contribution of the social sciences in the prevention of and response to infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance. https://sonar-global.eu/

NOHA is an international consortium of universities seeking to enhance humanitarian professionalism https://www.nohanet.org/

The element of ethnicity, class or cast can also have a direct impact in this person-driven approach in contexts where these are factors that shape society and the interaction among people who are born and raised into this cosmovision. These elements can play a critical role in setting the social science research agenda.

Based on the research findings and collaborative process, a set of recommendations was collectively generated. These recommendations provide handles for the systematic integration of social science in community engagement in humanitarian action and work towards a power-sensitive approach for transdisciplinary research and humanitarian programming. They are described more thoroughly and with more detailed suggestions for action, in the report that resulted from the project (UNICEF 2023).

References

Abramowitz SA, Hipgrave DB, Witchard A, Heyman DL (2018) Lessons from the West Africa Ebola epidemic: a systemativ review of epidemiological and social and behavioral science research priorities. J Infect Dis 218:1730–1738. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy387

Alexander J (2015) Informed decision making: Including the voice of affected communities in the process. In: CHS Alliance, On the Road to Istanbul: How can the World Humanitarian Summit make humanitarian response more effective? Humanitarian Accountability Report, Chapter 12. CHS Alliance, Geneva. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/road-istanbul-how-can-world-humanitarian-summit-make-humanitarian-response-more

Ashworth HC, Dada S, Buggy C, Lees S (2021) The importance of developing rigorous social science methods for community engagement and behavior change during outbreak response. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 15(6):685–690. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.163

Bardosh KL, de Vries DH, Stellmach D, Abramowitz S, Thorlie A, Cremers L, Kinsman J (2019) Towards people-centred epidemic preparedness and response: from knowledge to action. Wellcome Trust, London

Bardosh KL, de Vries DH, Abramowitz S, Thorlie A, Cremers L, Kinsman J, Stellmach D (2020) Integrating the social sciences in epidemic preparedness and response: a strategic framework to strengthen capacities and improve Global Health security. Glob Health 16(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00652-6

Barnett M (2021) Humanitarian organizations won’t listen to groups on the ground, in part because of institutionalized racism. CHS Alliance. URL: https://www.chsalliance.org/get-support/article/institutionalized-racism-research/

Batniji R, van Ommeren M, Saraceno B (2006) Mental and social health in disasters: relating qualitative social science research and the Sphere standard. Soc Sci Med 62(8):1853–1864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.050

Carter SE, Gobat N, Zambruni JP, Bedford J, Van Kleef E, Jombart T, Ahuka‐Mundeke S (2020) What questions we should be asking about COVID‐19 in humanitarian settings: perspectives from the social sciences analysis cell in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMJ Glob Health 5(9):e003607

CHS Alliance (2014) The core humanitarian standard on quality and accountability. CHS Alliance, Group URD and the Sphere Project. https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/the-standard/language-versions

Delgado M (2021) Political advocacy in Colombia: impact evaluation of the “Building peace by securing rights for victims of conflict and violence in Colombia” project. Oxfam, Oxford

Duncan A (2014) Integrating science into humanitarian and development planning and practice to enhance community resilience: Full guidelines (UCL) (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/duncan-et-al-2013-draft-feb2014.pdf . Accessed 24 Dec 2021 )

European Commission (2021) Ethics in social science and humanities. European commission, DG research & innovation, research ethics and integrity sector, Brussels (https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/horizon/guidance/ethics-in-social-science-and-humanities_he_en.pdf)

Freire P (1982) Creating alternative research methods: learning to do it by doing it. In: Hall B, Gillette A, Tandon R (eds) Creating knowledge: a monopoly? Participatory research in development. Society for Participatory Research in Asia, New Delhi, India, pp 29–40

Gibbs L, Waters E, Bryant RA et al. (2013) Beyond bushfires: community, resilience and recovery - a longitudinal mixed method study of the medium to long term impacts of bushfires on mental health and social connectedness. BMC Public Health 13 (1036). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1036

Giles-Vernick T, Kutalek R, Napier D, Kaawa-Mafigiri D, Dückers M, Paget J et al (2019) A new social sciences network for infectious threats. Lancet Infect Dis 19(5):461–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30159-8

Goldacre B, Harrison S, Mahtani KR, Heneghan C (2015) WHO consultation on data and results sharing during public health emergencies: background briefing. CEBM/University of Oxford Centre for evidence-based medicine and Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, Oxford

Harper K, Gubrium A (2017) Visual and Multimodal Approaches in Anthropological Participatory Action Research. General Anthropology, 24: 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/gena.12028

Hilhorst D, Bankoff G (eds) (2022) Why vulnerability still matters: the politics of disaster risk creation. Routledge, London

IASC (2017) Revised accountability to affected populations commitments (https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/accountability-affected-populations-including-protection-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse/documents-61 . Accessed 21 Jan 2022 )

Janes C, Corbett K (2009) Anthropology and global health. Annu Rev Anthropol 38:167–83. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164314

Laverack G, Manoncourt E (2016) Key experiences of community engagement and social mobilization in the Ebola response. Glob Health Promot 23(1):79–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975915606674

Le Marcis F, Enria L, Abramowitz S, Mari-Saez A, Faye S (2019) Three acts of resistance during the 2014–16 West Africa Ebola epidemic: a focus on community engagement. J Humanitar Affairs 1:23–31. https://doi.org/10.7227/JHA.014

London AJ (2005) Justice and the human development approach to international research. Hast Cent Rep 35:24–37

Matenga T, Zulu JM, Corbin JH, Mweemba O (2021) Dismantling historical power inequality through authentic health research collaboration: Southern partners’ aspirations. Glob Public Health 16(1):48–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1775869

Nichter M (2018) Global Health. In: The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, H Callan (ed). Wiley Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea2174

Niederberger E, Knight L, O’Reilly M (2018) An introduction to community engagement in WASH. Oxfam, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.21201/2018.3897

OCHA (2023) The humanitarian programme cycle (https://www.ochaopt.org/coordination/hpc . Accessed 25 Aug 2023 )

OCHA (2015) OCHA on message: what is community engagement? (https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/world/ocha-message-community-engagement . Accessed 17 Mar 2022 )

O’Dempsey T, Munslow B (2009) ‘Mind the gap!’ rethinking the role of health in the emergency and development divide. Int J Health Plan Manag 24:S21–S29. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.1020

Oliver-Smith A, Hoffman SM (2002) Introduction: why anthropologists should study disasters. In: Oliver-Smith A, Hoffman SM (eds) Catastrophe and Culture: the anthropology of disaster. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe

Osborne J, Paget J, Giles-Vernick T, Kutalek R, Napier D, Baliatsas C, Dückers M (2021) Community engagement and vulnerability in infectious diseases: a systematic review and qualitative analysis of the literature. Soc Sci Med 284:114246

Panter-Brick C (2022) Energizing partnerships in research-to-policy projects. Am Anthropol 124:75166

Pratt B (2020) Developing a toolkit for engagement practice: sharing power with communities in priority-setting for global health research projects. BMC Med Ethics 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-0462-y

Pratt B, Cheah PY, Marsh V (2020) Solidarity and Community Engagement in Global Health Research. Am J Bioeth 20(5):43–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1745930

Richards P (2016) Ebola: how a people’s science helped end an epidemic. African Arguments. Zed Books, London

Richardson ET, Barrie MB, Kelly JD, Dibba Y, Koedoyoma S, Farmer PE (2016) Biosocial approaches to the 2013–2016 Ebola pandemic. Health Human Rights 18:115–128