Abstract

Background

The authors introduced a rare case of intracranial malignant melanoma.

Case presentation

A 32 year-old male patient presented to the hospital with signs and symptoms commonly seen in the presentation of a hemorrhagic stroke. The patient was diagnosed as having an Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM) after a thorough history, physical examination and radiographic imaging were performed and assessed. However, intraoperative findings and postoperative histopathology findings revealed that the supposed AVM was in fact a malignant melanoma, appearing as an AVM of the brain, on radiographic imaging.

Conclusion

After reviewing related literature, our team realized that it was a rare finding for a melanoma pretending as a brain AVM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malignant melanoma (MM) is one of the most common tumors that metastasize to the brain. It usually presents with mass effect or intracranial hemorrhage with single or multiple lesions. In this paper, we present an atypical case of MM with a clinical presentation much like that of an Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM), and discuss related literature regarding metastatic intracranial melanoma.

Case presentation

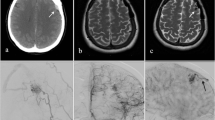

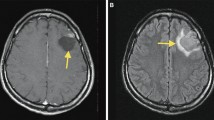

A 32-year-old Han Chinese man was admitted to the Neurology Department of our institution with the chief complaint of headache for 10 days. During the 3 days before admission, the patient experienced an increase in headache severity as well as other symptoms: nausea, vomiting and occasional attacks of vertigo. The headache was described as a sudden onset of generalized pain encompassing the entire brain without any apparent inciting event. The pain was felt to be worse at night and no epileptic episodes were noted prior to admission. The symptoms could not be relieved by rest, and the patient complained of generalized pain unaffected by physical activity or rest. No neurological deficits were observed on physical examination. After admission, the patient experienced a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, which lasted for about 1 min. He had a Grade IV weakness of the right extremities, a right partial paresthesia and a positive Babinski’s sign on the right side. Computed tomography (CT) of the head from another local hospital showed an intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) of the left occipital lobe accompanied by subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (Fig. 1a and b). Furthermore, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography (MRA) revealed an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the left posterior watershed area with accompanying ICH and SAH (Fig. 1c–e). The patient was transferred to the neurosurgical department for Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) examination. An AVM of the left occipital-parietal lobe (4.1 cm × 4.5 cm in size) was observed on DSA, with feeding arteries originating from the middle cerebral artery (MCA) branch. The venous drainage was superficial to the superior sagittal sinus. An enlarged left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) was also observed on angiography with unremarkable distal findings (Fig. 1f–k).

These figures show the imaging feature of this young male patient. a–f CT and MRI, MRA scans show hematoma of the left occipital lobe, and enlarged vessels connected to the mass. g–k DSA and 3D-DSA manifestations of the “AVM” mass with feeding arteries and draining veins. l The intraoperative view of the darker vessels with enlarged draining veins laying on the surface of the brain surface. m and n The pathological manifestation of the mass on immuno-chemico-histological stains of both HMB45 and S-100 (the brown deposition demonstrated the existence of melanin). o and p The scattered and silent systematic dermatologic lesions of malignant melanoma that were discovered after surgery

Craniotomy of the left occipital-parietal lobe for the removal of the lesion and hematoma evacuation was performed under general anesthesia. During the surgical operation, several enlarged veins distal to the AVM contained blood draining to the superior sagittal and transverse sinus on the anterior surface of the occipital lobe (Fig. 1l). Three major feeding arteries extending from the MCA, found beneath the lesion, anterior to the lateral fissure, were cauterized. During the operation, a hematoma was observed to be surrounding the lesion and was subsequently removed. Several smaller feeding arteries from the PCA were found after removing the lesion from the local brain tissue. After all the small feeders were isolated, the distal veins turned dark, and a significant reduction of the size of lesion was observed. The draining veins were then cauterized after the total resection of the lesion, which measured 5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm in size. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient had no complaints of neurological deficits, or epileptic episodes after admission, with no vision loss or motor dysfunction bilaterally. Laboratory results returned a decreased hemoglobin level (123 g/L compared to that of 140 g/L before surgery) and an increased white blood cell level (14 × 109/L, neutrophil account for 86% compared to that of previous assessment 8.9 × 109/L, neutrophil account for 66%). Pathological examination revealed a left leptomeningeal occipital-parietal melanoma that was visualized on immunohistochemistry staining (1:20, HMB45++, GFAP -, EMA +, CK -, Vim ++, S-100 ++) (Fig. 1m and n).

The initial diagnosis made in this case was AVM, as all of the patient’s symptoms (age of onset, short period of sudden headache, only one episode of epilepsy recorded after admission), diagnostic imaging and surgical procedures identified with AVM. However, further immunohistochemistry findings confirmed that the mass was a melanoma of metastatic origin. Upon postoperative examination of the patient, it was noticed that the patient had two dark brown to black lesions, one on the dorsal surface of the right elbow, and another on the right buttock (Fig. 1o and p). The patient was unaware of these lesions and refused to undergo biopsy for verification.

No neurological deficits, dysfunction, vision loss or right sided paralysis was recorded at discharge. A month after discharge, the patient was followed up on the phone. The patient had been admitted to a community hospital for oliguria, and he denied further treatment because of his poor financial economic state and refused follow up thereafter.

Discussion

Malignant melanoma (MM) is one of the most common tumors that metastasize to the brain [1], with nonspecific presentation as the other intracranial lesions [2, 3]. About 70.6% of melanoma patients had cerebral metastasis at younger than 65 years of age [4]. It is also one of the most common tumor types leading to intracranial hemorrhage [5, 6] and even multiple hemorrhages [2, 4–7]. In addition to having a hemorrhagic presentation, MM may have three subtypes of imaging features on MRI: melanoma, non-melanoma and uncertain/mixed. Hemorrhage and solid melanoma accounted for approximately 70% of all intracranial melanomas [8, 9]. Based on the literature mentioned above, we concluded that MM tends to metastasize to the brain in the middle aged or younger population. MM most commonly presents as a solid, single/multiple lesion (s). It rarely presents as a vascular malformation. Meanwhile, ICH can occur within the tumor, and/or into the brain, with or without the presence of SAH.

The patient in this case presented with a sudden headache with typical signs and symptoms of ICH and SAH. The lesion originally identified, was misdiagnosed as an AVM until pathological examination confirmed otherwise. The lesion most likely metastasized from asymptomatic dermatologic lesions, which were discovered postoperatively. The patient refused to take dermatologic biopsy that makes this intracranial MM a probable metastatic melanoma. Even though melanoma of the central nervous system is often misdiagnosed, the misdiagnosis of metastatic melanoma for AVM is a rare occurrence [9–13]. Another case reported malignant melanoma metastasized into a pre-existing intracranial cavernoma with a hemorrhagic presentation [14]. A more recently published case reported recurrent choriocarcinoma of the testis metastasized to a pre-existing AVM of the left occipital lobe [15]. In the present case, although DSA suggested that the lesion most represented an AVM, we excluded the possibility of a pre-existing AVM based on pathological examination, as the specimen showed no definite fibrous structure related to vessel formation.

Malignant metastatic melanoma, like other malignant neoplasms, may invade and localize to the vessels of the central nervous system, including areas such as the gray-white junction and the watershed area [16, 17]. As tumor-induced angiogenesis increases vascular permeability and disrupts the blood–brain barrier. It may result in morphological and functional changes to the vessels in the brain [17]. The theory could explain why intracranial metastasis leads to ICH. Additionally, this could further explain why the MM presented as an AVM in this case. AVMs of the central nervous system are relatively uncommon with a prevalence of <1% and an incidence of between 0.01 and 0.001%, and lead to acute intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and seizure in middle-aged men (mean age at presentation was 33.7 years old) population [5, 18–20]. Given the patient’s young age of 32 years, and the medical history supported by imaging, the diagnosis was more likely caused by stroke onset.

Options are limited for the treatment of MM of the brain. Standard treatment models include surgical resection of the tumor, whole brain radiotherapy, stereotactic radiosurgery and chemotherapy [5, 16, 17, 20]. The administered treatment is largely dependent on the size, number of lesions and the extracranial extension of the original lesions. Although there may be debate on whether to operate on a Grade 3 “AVM” or not, due to the risk of sacrificing the patient’s vision, we chose surgery, for this case, as the patient came with sudden-onset headache, which turned out to be due to tumor stroke. The visual cortex was well protected during operation and the patient’s vision was intact postoperatively. We went back to analyze what led to the lack of awareness of a melanoma in this case. First of all, the lesion presented as an atypical melanoma with scattered yet asymptomatic dermatologic lesions. Secondly, the patient presented with signs of hemorrhage, which were shown by CT and MRI scan as well as an epileptic episode, suggestive of AVM rupture. Finally, the DSA examination demonstrated structural lesions representative of a typical AVM: feeding arteries with an abundant blood supply from both the MCA and PCA, as well as enlarged veins draining to superior sagittal and transverse sinuses, which we confirmed during the intraoperative course. In addition, we found that the hematoma of this lesion was significantly darker in color compared to a typical hematoma caused by AVM rupture. The hematoma was contained in vessel masses that were more morphologically similar to AVM thrombosis. These features may be helpful to distinguish the two lesions intraoperatively.

Conclusions

This case provides us with a good learning opportunity, which is to increase recognition and awareness of rare clinical presentations of malignant melanoma. The clinical presentation of metastatic intracranial melanoma may be atypical in nature. Such atypical presentations should be taken into consideration by attending physicians. Lastly, physicians should be more thorough and observant, by taking more comprehensive medical histories and by conducting more detailed physical examinations when approaching similar cases.

Abbreviations

- AVM:

-

Arteriovenous Malformation

- CK:

-

Creatine kinase

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DSA:

-

Digital subtraction angiography

- EMA:

-

Epithelial membrane antigen

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HMB45:

-

Human Melanoma Black 45

- ICH:

-

Intracranial Hemorrhage

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

- MM:

-

Malignant melanoma

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance angiography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PCA:

-

Posterior cerebral artery

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- Vim:

-

Vimentin

References

Lavine SD, Petrovich Z, Cohen-Gadol AA, et al. Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for Metastatic Melanoma: an analysis of survival, outcome, and complications. Neurosurgery. 1999;1:59–64. 64–66.

Liubinas SV, Maartens N, Drummond KJ. Primary Melanocytic Neoplasms of the Central Nervous System. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;10:1227–32.

Kusters-Vandevelde HV, Klaasen A, Kusters B, et al. Activating Mutations of the GNAQ Gene: A Frequent Event in Primary Melanocytic Neoplasms of the Central Nervous System. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;3:317–23.

Freudenstein D, Wagner A, Bornemann A, Ernemann U, Bauer T, Duffner F. Primary Melanocytic Lesions of the CNS: Report of Five Cases. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2004;3:146–53.

Miller D, Zappala V, El HN, et al. Intracerebral Metastases of Malignant Melanoma and their Recurrences--A Clinical Analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;9:1721–8.

Wronski M, Arbit E. Surgical Treatment of Brain Metastases From Melanoma: A Retrospective Study of 91 Patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;1:9–18.

Wang J, Guo ZZ, Wang YJ, Zhang SG, Xing DG. Microsurgery for the Treatment of Primary Malignant Intracranial Melanoma: A Surgical Series and Literature Review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;9:1062–71.

Isiklar I, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, Kumar AJ. Intracranial Metastatic Melanoma: Correlation Between MR Imaging Characteristics and Melanin Content. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;6:1503–12.

Chan CH, Fabinyi GC, Kalnins RM. An Unusual Case of Tumor-To-Cavernoma Metastasis. A Case Report and Literature Review. Surg Neurol. 2006;4:402–8. 409.

Sundarakumar DK, Marshall DA, Keene CD, Rockhill JK, Margolin KA, Kim LJ. Hemorrhagic Collision Metastasis in a Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-011362.

Sundarakumar DK, Marshall DA, Keene CD, Rockhill JK, Margolin KA, Kim LJ. Hemorrhagic Collision Metastasis in a Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7(10):e34.

Crawford PM, West CR, Chadwick DW, Shaw MD. Arteriovenous Malformations of the Brain: Natural History in Unoperated Patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;1:1–10.

Ondra SL, Troupp H, George ED, Schwab K. The Natural History of Symptomatic Arteriovenous Malformations of the Brain: A 24-Year Follow-Up Assessment. J Neurosurg. 1990;3:387–91.

Gross BA, Du R. Natural History of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformations: A Meta-Analysis. J Neurosurg. 2013;2:437–43.

Hernesniemi JA, Dashti R, Juvela S, Vaart K, Niemela M, Laakso A. Natural History of Brain Arteriovenous Malformations: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study of Risk of Hemorrhage in 238 Patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;5:823–9. 829–831.

Bafaloukos D, Gogas H. The Treatment of Brain Metastases in Melanoma Patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;6:515–20.

Fisher R, Larkin J. Treatment of Brain Metastases in Patients with Melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2012;5:434–5.

Delattre JY, Krol G, Thaler HT, Posner JB. Distribution of Brain Metastases. Arch Neurol. 1988;7:741–4.

Long DM. Capillary Ultrastructure in Human Metastatic Brain Tumors. J Neurosurg. 1979;1:53–8.

Harrison BE, Johnson JL, Clough RW, Halperin EC. Selection of Patients with Melanoma Brain Metastases for Aggressive Treatment. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;4:354–7.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors’ contribution

YT, YH and JW contributed equally in the paper; BP and WY participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication of this case report has been acquired from the patient’s parents for academic exchange.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct this retrospective study. The approval number was 2016–0038.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Y., Hou, Y., Prasad, B. et al. Intracerebral malignant melanoma presenting as an Arteriovenous Malformation: case report and literature review. Chin Neurosurg Jl 3, 15 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-017-0075-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-017-0075-6