Abstract

Background

Ebsteins anomaly accounts for less than 1% of all congenital cardiac defects. Whilst typically characterised by dysfunction and anatomical defects of the right ventricle and tricuspid valve, it often co-exists with other congenital defects. Less frequently outflow tract obstruction may arise with associated haemodynamic effects and symptoms. In particular there are few reports in the literature of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. We believe this is because symptomatic outflow tract obstruction as the presenting complaint of this condition is exceptionally rare.

Case presentation

We report on a 17 year old male who was referred to the general cardiology clinic with symptoms of exertional fatigue and breathlessness. Transthoracic echocardiogram performed as part of the workup led to the diagnosis of Ebstein’s anomaly. In addition to the characteristic features of this congenital abnormality there was significant dilatation of the right atrium with resultant leftward bulging of the intraventricular septum. The anterior mitral valve leaflet was noted to be elongated with accessory chordal apparatus and demonstrated systolic anterior motion. Turbulence was noted in the left ventricular outflow tract leading to a degree of obstruction. Here we discuss the aetiology and mechanisms behind this unusual presentation.

Discussion

Ebstein’s anomaly arises due to chromosomal rearrangements affecting early morphogenesis of the right ventricle and tricuspid valve. Associations with other congenital defects such as interatrial communications are well documented. Less commonly the structural abnormalities of this condition lead to functional outflow tract obstruction. Whilst cases have previously described right ventricular outflow tract obstruction there are fewer reports of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in this patient group. The structural defects that result in dilatation of the right atrium and the atrialised portion of the right ventricle can lead to leftward bulging of the interatrial septum. Turbulence can occur in the left ventricular outflow tract with resultant systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in a mechanism similar to that encountered in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This may only become haemodynamically relevant during exertion.

Conclusion

In the absence of ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias or syncope we suggest that it is reasonable to adopt an observational strategy to the management of these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ebstein’s anomaly is a rare congenital cardiac defect that accounts for less than 1% of all cases of congenital heart disease. Indeed, by the 1950’s only 3 cases had been reported in medical literature [1]. Affecting approximately 1 in 200,000 live births this disorder is characterised by anatomical defects and dysfunction of the right ventricle and tricuspid valve. However, it is not uncommon for this disorder to be associated with other cardiac defects. Most commonly interatrial communications can be present in up to 94% of patients, this is followed in prevalence by mitral valve prolapse and left ventricular non-compaction [1,2,3]. Additionally, ventricular septal defects, pulmonary stenosis and pulmonary atresia have all been found to coexist in patients with Ebstein’s anomaly. As a result of these structural defects patients may suffer from functional impairment of the ventricles, valves and conduction system. Whilst right ventricular outflow tract obstruction has previously been described in these patients there are fewer reports of obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOTO) [1, 2].

Case presentation

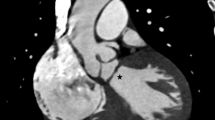

A 17 year old male was initially referred to the general cardiology department with progressive symptoms of fatigue and exertional dyspnoea. A keen cyclist, he had observed a marked deterioration in his functional capacity on extreme exertion. His past medical history and family history were unremarkable. Clinical examination revealed only a soft systolic murmur at the left sternal edge. As part of his workup a transthoracic echocardiography was performed resulting in the diagnosis of Ebstein’s Anomaly. The tricuspid valve was noted to be morphologically abnormal and apically displaced without significant regurgitation. The right atrium was significantly dilated and confluent with the atrialized portion of the right ventricle (Fig. 1). The functional right ventricle whilst reduced in size had preserved systolic function. In addition to these characteristic features of Ebstein’s the anterior mitral valve leaflet was noted to be elongated with accessory chordal apparatus and demonstrated systolic anterior motion (Figs. 2 and 3). No significant mitral valve prolapse or regurgitation was identified (Fig. 4). The dilatation of the right atrium resulted in significant leftward bulging of the interventricular septum. Doppler Colour flow of the left ventricular outflow tract demonstrated turbulence in keeping with a degree of obstruction however no significant resting gradient was identified on resting echocardiography (Fig. 5). The left atrium and ventricle were otherwise normal in both morphology and function.

In keeping with guideline recommendations for cardiovascular exercise in patients with congenital heart disease, he was advised to maintain physical activity aiming for 30–60 min of moderate to vigorous activity on a daily basis [4]. Clinical follow up by way of annual clinic review, clinical examination and annual echocardiography has revealed that his symptoms and ventricular function have remained stable during the 30 years of follow up. In the absence of any medical intervention he has not suffered any decompensation episodes or acute hospital admissions and continues to enjoy low intensity cycling and working in a physically demanding job as a pig farmer.

Discussion

Symptomatic outflow tract obstruction represents an unusual presentation of Ebstein’s anomaly. Whilst more commonly associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy the haemodynamic consequences are similar and may lead to symptoms of breathlessness particularly during periods of exertion. To understand the mechanism of LVOTO it is important to review the pathological anatomy of Ebstein’s anomaly. Early morphogenesis of the right ventricle and tricuspid valve are coded on the long arm of chromosome 15 and abnormalities in these gene sequences are likely to be involved in Ebstein’s anomaly [3]. Additionally, chromosomal rearrangements on the long arm of chromosome 11 have been identified in 2 patients with Ebstein’s [3]. As a result of these abnormalities the tricuspid valve leaflets fail to delaminate during development leading to valve dysplasia and right ventricular malformation. Characteristically the septal and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve adhere to the underlying myocardium, the valve annulus becomes apically displaced, the atrialized portion of the right ventricle dilates and the anterior leaflet tethers, and is often fenestrated and becomes redundant [1, 2]. The degree of deformation of the anterior leaflet can lead to its displacement into the right ventricular outflow tract and result in obstruction.

The right ventricle becomes divided into two distinct regions, the dilated atrialized portion and the functional portion consisting of the trabecular apical region of the right ventricle and the outflow tract. The true undisplaced tricuspid annulus is often significantly dilated. Varying degrees of regurgitation through the dysplastic valve can occur leading to further and progressive dilatation of the atrialized portion of the right ventricle. As a result of the dilatation of the true annulus and the atrialized portion of the right ventricle the interventricular septum can display leftward bulge and encroach on the left ventricular outflow tract potentially leading to obstruction which may only become haemodynamically relevant during exertion. The turbulence created in the outflow tract can lead to flow acceleration across the narrowed orifice and the development of systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve leaflet. The mechanism of this is proposed to be similar to that encountered in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [5]. Whilst some debate exists as to the true mechanism of SAM it is likely to be due to a combination of lift and drag at low velocities and the venturi effect at higher velocities [5]. Indeed Sherrid et al. demonstrated that SAM begins at low velocity when the venturi forces are present at a relatively low magnitude. Their study indicated that the hydrodynamic force that predominates at low velocity is the drag effect due to the pushing force of flow [5].

In addition to the above pathology our patient also demonstrated evidence of accessory mitral valve tissue. Whilst this accessory tissue represents a relatively rare congenital defect it often co-exists with other congenital anomalies [6]. In keeping with the development of the tricuspid valve, early morphogenesis of the mitral valve requires separation of the endocardial cushions and this perhaps explains the co-existence of these conditions. The presence of accessory tissue leads to an increased mass effect and turbulence in the outflow tract with associated fibrous tissue deposition. This has been shown to result in SAM and outflow tract obstruction [6].

Whilst an elevated outflow tract velocity was not demonstrated at rest on transthoracic echocardiography in our patient it is likely that the outflow tract obstruction secondary to the dual pathology of Ebstein’s with left septal bulge and accessory mitral valve tissue leads to haemodynamic significance during extreme exertion.

Conclusion

Whilst Ebsteins Anomaly remains a rare form of congenital heart disease it is important to appreciate that it is often accompanied by other congenital defects. Atypical symptoms should prompt thorough investigation and review of imaging by experts in this field. The possibility of outflow tract obstruction should be considered in patients reporting exertional shortness of breath. In the absence of ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias or syncope we suggest that it is reasonable to adopt an observational strategy to the management of these patients by way of annual clinical review and echocardiography.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- LVOTO:

-

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- SAM:

-

Systolic anterior motion

References

Attenhofer Jost CH, et al. Ebstein’s anomaly. Circulation. 2007;115:277–85.

Hirata K, et al. Case of Ebstein anomaly complicated by left ventricular outflow tract obstruction secondary to deformed basal septum attributable to atrialized right ventricle. Circulation. 2016;133:e33–7.

Shi-min Y. Ebstein’s anomaly: genetics, clinical manifestations, and management. Paediatr Neonatol. 2017;58:211–5.

Longmuir E, et al. Promotion of physical activity for children and adults with congenital heart disease. A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2013;127:2147–59.

Sherrid MV, et al. Systolic anterior motion begins at low left ventricular outflow tract velocity in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC. 2000;36(4):1344–54.

Manganaro R, et al. Accessory mitral valve tissue: an updated review of the literature. Eur Heart J. 2014;15:489–97.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained by either author for completion/ research of this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG was major contributor to writing this manuscript. AG and NM were jointly responsible for selecting images for inclusion in this manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. AG is author for correspondence.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval has not been required for this case report.

Consent for publication

Patient consent has been received for use of anonymised images and case report presentation. Consent form available on request.

Competing interests

Neither author holds a competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, A.P., Mahon, N.G. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction secondary to right atrial dilatation and accessory mitral valve tissue in a patient with Ebstein’s anomaly- Case report. J Congenit Heart Dis 3, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40949-019-0028-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40949-019-0028-3