Abstract

Background

The variable visual function observed in diabetic retinopathy (DR) patients is not fully explained by the classic staging system. Our purpose was to evaluate choroidal changes, in standardized sectors, in DR patients and to find associations between choroidal measurements and visual function.

Methods

Cross-sectional study that included the right eye of diabetic patients (n = 265) without active edema, ischemia or neovascularization and age-matched controls (n = 73). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging was performed with enhanced depth imaging protocol. Choroidal vascularity index (CVI) was calculated in a 5 mm scan centered in the fovea.

Results

CVI decreased with age (p < 0.001) but was not influenced by axial length. A multivariate analysis adjusting for age confirmed a significant difference in CVI between DR eyes that had previous treatments (intravitreal injections and/or photocoagulation) compared to control eyes (p = 0.013) and to DR eyes that never required treatment (p = 0.002). There was no significant difference between non-DR diabetic patients and normal controls. Considering the group of DR patients that had previous treatments, in eyes without optic media opacification, BCVA correlated with CVI (r = − 0.362, p < 0.001), whereas full retina thickness and individual retinal layer thickness did not (p > 0.066).

Conclusions

A reduction in CVI was observed in patients with a more advanced stage of DR. In treated DR patients with stable disease, choroidal biomarkers correlated with best-corrected visual acuity whereas retinal biomarkers did not.

Trial registration: N/A

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nearly half a billion people are dealing with diabetes mellitus (DM) [1]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) affects about one third of DM patients [2], which makes it the leading cause of visual loss in the working-age population [3].

The effects of DM in the retinal vasculature and inner blood–retinal barrier are well established [4] and are the backbone of DR diagnosis and staging. Nonetheless, the retinal blood supply is more complex: the outer retinal layers and the foveal full-thickness retina are supplied by the choroidal vasculature and the associated external blood–retinal barrier [5]. These structures are hardly considered in today’s ocular diabetes practice.

Thanks to enhanced depth imaging (EDI) protocol [6] and swept-source optical coherence tomography (OCT), better in vivo visualization of the choroid is possible. Some groups have focused on choroidal thickness (CT) but it is a coarse measurement for such a complex tissue and no consensus has been reached [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Moreover, CT is influenced by several local and systemic factors [13,14,15].

More recently, choroidal vascularity index (CVI) has been described [16, 17]. CVI has been remarkably investigated in DM eyes [18,19,20,21]. However, most studies have limitations, namely: considering CVI and CT in non-corresponding and small areas [18,19,20]; comparing CVI in unstandardized width areas [19]; not stipulating if the suprachoroidal space was considered for analysis [18, 20]; not analyzing absolute choroidal luminal and stromal areas [18, 19] or not considering age and axial length as potential confounders for CVI [18].

Therefore, our purpose was to study the choroid in diabetic patients using CVI and its corresponding stromal, vascular luminal and total choroidal areas, in standardized widths. Secondarily, we aimed to analyze central, nasal, and temporal sectors.

Patients, materials and methods

Study design

Cross-sectional observational study set at the Ophthalmology Department of Centro Hospitalar e Universitário do Porto, Portugal, during February 2019 and February 2020.

Study population

DM patients were consecutively recruited, together with age-matched non-diabetic controls from routine appointments. Exclusion criteria were eyes with active macular edema, ischemia, or neovascularization; intraocular procedures in the previous 3 months or signs of concomitant retinal diseases or ocular inflammatory diseases. The estimated sample size (35 subjects per group) was calculated with a previous published formula [22], using the standard deviation of CVI found in previous studies (3%) [19], for a power of 80%, a significance level of 5%, to find a 2% difference in CVI.

Included subjects were further divided in non-DM eyes (group 1), non-DR diabetic eyes (group 2), non-treated DR group (no requirement for treatment, postulating an early stage, group 3) and treated DR group (required treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF or corticosteroids and/or with focal or panretinal photocoagulation (PRP), as a more advanced stage of the disease, group 4).

Study protocol

Demographic data and medical history were recorded, namely previous ocular surgeries, photocoagulation with LASER, either focal or PRP, and intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF or corticosteroids. Axial-length was collected from the patients’ charts.

In the study visit, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) converted to logMAR, intraocular pressure (IOP) with Goldmann tonometer, slit-lamp biomicroscopy and fundus examination under mydriasis were evaluated. Macular spectral-domain OCT (Heidelberg Spectralis, Germany) high-resolution (1024 horizontal pixels, 20°) imaging was performed with and without EDI protocol [6] and with automatic real-time image averaging set at 100 images. Individual retinal layers were automatically segmented and measured in the central 5 mm, with the proprietary Heidelberg Eye Explorer® software. Each scan was checked for erroneous segmentation.

Imaging protocol

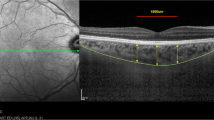

Scans with ambiguous choroid/sclera boundary, erroneous centration or poor acquisition quality were excluded from analysis. A B-scan centered in the fovea was exported in a 1:1 μm proportion and a semi-automated macro analyzed the choroid (detailed in Additional file 1):

-

1.

The OCT scale was automatically read to calculate its true resolution (μm/pixel) and the image was automatically cropped to a centered 5 mm-width standard, independent of the width in pixels (Fig. 1).

-

2.

Choroid limits were manually drawn one single time by a single investigator who was masked to the patients’ clinical information. This was the only manual step in our protocol. The outer border of the hyperreflective line representing the retinal pigment epithelium was considered the inner choroidal limit. The outer choroidal limit was defined as inner border of the hyperreflective sclera. The presence of a visible suprachoroidal space (SCS), defined as a continuous homogenous hyporeflective layer between the choroid and the sclera (Fig. 2), was recorded and, in such cases, SCS was not considered part of the choroid.

-

3.

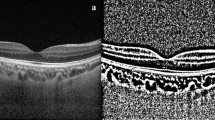

Binarization of the OCT image was performed automatically using the same tools as previous studies [16, 17].

-

4.

The choroidal area (CA), hyperreflective stromal area (SA) and hyporeflective vascular luminal areas (LA) were automatically calculated in the full 5 mm-width image (G) and in 1 mm-width central (C), nasal (N) and temporal (T) sectors. CVI was calculated as LA/CA. CA was converted to average CT by dividing it by the corresponding width.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed only one eye per subject, and we always choose the same eye (right eye) because of the slightly asymmetrical arterial supply (due to the aortic anatomy).

After confirmation of normal distribution of variables and homogeneity of variances, Student’s t-test was used to compare variables between two groups. One-way ANOVA test was used for multiple group comparison and Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc analysis was used to adjust the significance. Univariate and multivariate linear regression and Person’s correlation coefficient were used to correlate the outcomes with independent variables. To assess the variability of the outcomes, the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated as standard deviation divided by mean.

Values are show as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise specified. All p-values (p) are 2-sided, and p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

Initially, 381 subjects were included. Due to ambiguous choroid/sclera boundary, erroneous centration and/or poor acquisition quality, 63 eyes (16.5%) were then excluded. Therefore, we considered for analysis 318 subjects, 58.2% of which were female. They comprised 265 diabetic subjects (67.4 ± 11.9, range 34–90 years-old) and 73 control non-diabetic subjects (72.2 ± 7.5, range 56–85 years-old). The number of subjects, demographic and clinical information per group are stated in Table 1.

Possible confounders

CT-G, SA-G and LA-G diminished with age (p < 0.001). LA-G revealed more pronounced decrease than SA-G (− 0.011 mm2/year vs − 0.004 mm2/year), so that CVI-G also decreases with age (− 0.09% per year, p < 0.001). The same changes were seen in a subanalysis including only healthy subjects (group 1, p < 0.017 for all).

The prevalence of arterial hypertension (AHT) was higher in DM patients (p = 0.018). It did not affect CVI-G (p = 0.216), even when considering the severity of DR as confounder (p > 0.384 in a subanalysis per group).

Axial length data was available in 127 subjects, and it did not differ among groups (ANOVA, p = 0.148). Contrarily to CT-G (− 20.5 μm per mm, p < 0.001), SA-G (− 0.04 mm2 per mm, p < 0.001) and LA-G (− 0.06 mm2 per mm, p = 0.001), axial length did not influence CVI-G (p = 0.301) as it is the result of LA and SA that changed in the same direction.

No differences in outcomes were found regarding the type of DM when adjusting for age. No correlation was found between the outcomes and the last HbA1c value.

Comparison among groups

A comparison among the multiple groups found a difference in CVI-G and CVI-T (ANOVA test, p = 0.042 and p < 0.001, respectively) but no significant differences in the other outcomes (ANOVA test, p > 0.124). A post-hoc analysis of CVI-G for multiple comparisons is detailed in Table 2 and Fig. 3.

A multivariate analysis adjusting for age confirmed a significant difference in CVI-G between groups 1 and 4 (β = − 0.091%/year, p = 0.001 for age and β = − 1.80%/group, p = 0.013 for the groups) and between groups 3 and 4 (β = − 0.101%/year, p = 0.001 for age and β = − 1.55%/group, p = 0.002 for the groups) but no differences among the other groups (p > 0.403).

Analysis of the treated-DR group

No differences in outcomes were found according to treatment with insulin (n = 108, p > 0.159 for CVI) or previous treatment with IVI (n = 23, p = 0.238 for CVI). Patients that underwent PRP had a lower CVI (64.08 ± 4.30 vs 66.63 ± 3.43, p < 0.001).

Associations with visual acuity

Table 3 shows possible associations between logMAR BCVA and CT, CVI, full retinal thickness and individual retinal layers thickness, in the full sample and by group, excluding eyes with optical media opacities (n = 214). Figure 4 demonstrates the correlation between CVI and logMAR BCVA. Age, a potential confounding factor, was not associated with logMAR BCVA (p = 0.343).

Comparison between outcomes

Distribution of outcomes per sector is shown in Table 4. SA-N, LA-N and CT-N were significantly thinner than their T or C counterparts (p < 0.001 for all pairs). CVI-T was lower than its N or C counterparts (p < 0.001).

CVI provided less intersubject variability than CT (CV 0.061 and 0.326, respectively, in the G sector). Measuring CVI in a 5 mm-width provided less intersubject variability than in central 1 mm-sector C (CV 0.061 and 0.072, respectively).

No choroidal measurement correlated with full thickness retinal thickness or any individual layer thickness (p > 0.177 for all pairs).

Presence of a visible suprachoroidal space

The SCS was visible in 61 subjects and was associated with a reduced CVI (64.17 vs 66.13%, p < 0.001 for CVI-G). We found no significant differences in our other outcomes regarding a visible SCS (p > 0.185).

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this is the largest study about the choroid in DM patients and the first one to consider standardized areas (5 mm and 1 mm) and individual sectors (G, C, T and N). Our results corroborate previous reports [18,19,20,21] and attempt to overcome some their limitations. For the first time, we relate choroidal structure with visual function.

CVI seems to be a better biomarker of the choroidal vascular structure than CT. It is less influenced by secondary factors than CT, such as axial length and AHT. Nevertheless, CVI decreases with age, even in healthy eyes. Likewise, the retinal vascular density accessed with OCT-angiography decreases with age [23] and, together, these changes may reflect systemic age-related vascular dysfunction [24].

Contrarily, a recent study by the group of Hao Zhou et al., that used swept-source OCT and a fully automated volumetric algorithm, found an inverse correlation of age with vascular volume and with stromal volume but not with CVI. This disparity may be explained by the different age distribution of the groups (55 ± 19 in their sample and 72 ± 7 years in our healthy eyes group). Thus, a non-linear relation between age and CVI may be considered, where CVI decreases with age, later in life.

We report a decrease in CVI in patients with DR that required treatment when compared to normal subjects and to DR patients that did not require treatment, independently of changes in LA, SA, or CT. The fact that our control group was older and that we performed a multivariate analysis reinforces the meaning of our findings regarding a truly reduced CVI due to DR. Despite their limitations, previous studies in DM patients using CVI also found a reduction in CVI as DR worsens [18,19,20,21].

Our grouping protocol promotes the differentiation of early stages of the disease and attempts to mimic clinical practice setting. Our methodology excluded patients with active edema, ischemia, or neovascularization. These aggravating factors may be independent causes for changes in choroidal blood flow and for changes in visual function.

Interestingly, we found no significant differences in groups 2 and 3 (early stages) when compared to the control group. The small size of these groups, the different age, the higher variability of measurements or a true absence of difference may justify not reaching significance. Some previous studies have found a reduced CVI in DM patients without DR [25,26,27], while other have not [18,19,20,21]. It remains unclear if diabetic choroidopathy can be detected before classic retinopathy. Considering the different findings and higher variability of CVI in non-DR diabetic eyes, we hypothesize that this group includes eyes in diverse subclinical stages, possibly with different risk of progression to DR. Thus, future studies should analyze prospectively the role of choroidal parameters in predicting the development of DR in diabetic patients.

Globally, our findings relate to choroidal medium and large vascular network attenuation in DR. Additionally, OCT angiography is showing increasing interest in diabetic retinopathy [28]. Most studies [29,30,31] have reported changes in the choriocapillaris, the small and capillary vessel layer, of diabetic eyes even with no clinical signs of retinopathy [31]. In addition, in healthy eyes, choriocapillaris flow in OCT-A seems to have a relation with choroidal stroma and vascular lumen in structural OCT [26]. A multimodal approach will probably achieve more elucidative conclusions.

Regarding associations with visual function, in the full sample, the outer nuclear layer thickness correlated with BVCA. This association has been previously described in diabetic patients [32]. However, in the present study, the correlation of BCVA with CVI was stronger and independent of the outer nuclear layer thickness. In the treated-DR subgroup, BCVA correlated only with CVI. The correlations in the full sample must be interpreted carefully as they may be driven by the treated DR group. It is unclear if this is a cause or a consequence of a common process: the retinal photoreceptors depend on the choroid [5] for their nutrient supply but, on the other side, the choroid may suffer changes after photoreceptor atrophy [33]. Choroid vascular status may help understand the different visual acuity sometimes observed in DR, that retinal biomarkers cannot fully explain.

We found the 5 mm-width area to be more sensitive than 1 mm-width area and, additionally, to have lower variability. Agrawal et al. compared, in normal eyes, three different scanning areas: single full-width foveal scan; volumetric central 1 mm scans and volumetric total macular scans. They reported good reliability using single full-width foveal scans [34]. Additionally, we excluded the SCS as part of the choroid. Otherwise, it might have influenced the results, as it would have been considered vascular lumen and modify average CVI.

In our study, using SD-OCT with EDI protocol, we excluded 16.5% of images due to ambiguous choroid/sclera boundary, erroneous centration and/or poor acquisition quality. Theoretically, the choroid/sclera outer limit visualization worsens as CT and SA (where most choroidal pigment lays) increase. The use of swept-source OCT, with increased penetration through melanin, might overcome this limitation. Our study has some other limitations: its cross-sectional design; the manual and single time drawing of choroidal limits (although it was done by a single investigator to potentiate precision) and the uneven number of eyes in each group (which is a reflex of our methods and of real-life clinical practice).

Choroid investigation should continue, and it may contribute to improved staging of diabetic retinopathy. CVI may be a good biomarker of retinal and visual function in treated diabetic patients. Subsequent prospective studies should focus on how the choroid and CVI may predict the risk of developing DR in DM patients.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data is available on request to the corresponding author (JHM).

References

Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843.

Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556–64. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1909.

Antonetti DA, Klein R, Gardner TW. Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1227–39. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1005073.

Cunha-Vaz J, Faria de Abreu JR, Campos AJ. Early breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in diabetes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59(11):649–56. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.59.11.649.

Nickla DL, Wallman J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(2):144–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.12.002.

Spaide RF, Koizumi H, Pozonni MC. Enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(4):496–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.032.

Querques G, Lattanzio R, Querques L, et al. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography in type 2 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(10):6017–24. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-9692.

Sudhalkar A, Chhablani JK, Venkata A, Raman R, Rao PS, Jonnadula GB. Choroidal thickness in diabetic patients of Indian ethnicity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(12):912–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.176024.

Galgauskas S, Laurinavičiūtė G, Norvydaitė D, Stech S, Ašoklis R. Changes in choroidal thickness and corneal parameters in diabetic eyes. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.5301/ejo.5000677.

Esmaeelpour M, Považay B, Hermann B, et al. Mapping choroidal and retinal thickness variation in type 2 diabetes using three-dimensional 1060-nm optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5311–6. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-6875.

Lee HK, Lim JW, Shin MC. Comparison of choroidal thickness in patients with diabetes by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013;27(6):433–9. https://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2013.27.6.433.

Laíns I, Talcott KE, Santos AR, et al. Choroidal thickness in diabetic retinopathy assessed with swept-source optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2018;38(1):173–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000001516.

Wei WB, Xu L, Jonas JB, et al. Subfoveal choroidal thickness: The Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(1):175–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.048.

Han Y-S, Lim H-B, Lee S-H, Kim J-Y. Diurnal variation in choroidal and retinal thickness of the early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study macular subfields determined using swept-source optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmologica. 2015;233(3–4):192–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000375538.

Barteselli G, Chhablani J, El-Emam S, et al. Choroidal volume variations with age, axial length, and sex in healthy subjects: a three-dimensional analysis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2572–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.065.

Agrawal R, Gupta P, Tan KA, Cheung CMG, Wong TY, Cheng CY. Choroidal vascularity index as a measure of vascular status of the choroid: measurements in healthy eyes from a population-based study. Sci Rep. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21090.

Sonoda S, Sakamoto T, Yamashita T, et al. Choroidal structure in normal eyes and after photodynamic therapy determined by binarization of optical coherence tomographic images. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(6):3893–8. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14447.

Kim M, Ha MJ, Choi SY, Park YH. Choroidal vascularity index in type-2 diabetes analyzed by swept-source optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18511-7.

Gupta C, Tan R, Mishra C, et al. Choroidal structural analysis in eyes with diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema—a novel OCT based imaging biomarker. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0207435. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207435.

Wang H, Tao Y. Choroidal structural changes correlate with severity of diabetic retinopathy in diabetes mellitus. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-019-1189-8.

Wang JC, Laíns I, Providência J, et al. Diabetic choroidopathy: choroidal vascular density and volume in diabetic retinopathy with swept-source optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;184:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2017.09.030.

Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Jager KJ. Sample size calculations. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118(4):c319–23. https://doi.org/10.1159/000322830.

Hashmani N, Hashmani S, Murad A, Baig N. Macular vascular density at the superficial capillary plexus using the optical coherence tomography angiography. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:295–302. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S189515.

Donato AJ, Machin DR, Lesniewski LA. Mechanisms of dysfunction in the aging vasculature and role in age-related disease. Circ Res. 2018;123(7):825–48. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312563.

Foo VHX, Gupta P, Nguyen QD, et al. Decrease in Choroidal Vascularity Index of Haller’s layer in diabetic eyes precedes retinopathy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001295. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJDRC-2020-001295.

Lupidi M, Cerquaglia A, Gujar R, et al. Functional correlation between choroidal and retinal vascularity in low-grade diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57(8):983–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01507-7.

Aksoy M, Simsek M, Apaydın M. Choroidal vascularity index in patients with type-1 diabetes mellitus without diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(6):865–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2020.1846755.

Sun Z, Yang D, Tang Z, Ng DS, Cheung CY. Optical coherence tomography angiography in diabetic retinopathy: an updated review. Eye. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01233-y.

Nesper PL, Roberts PK, Onishi AC, et al. Quantifying microvascular abnormalities with increasing severity of diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(6):BIO307. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.17-21787.

Dai Y, Zhou H, Chu Z, et al. Microvascular changes in the choriocapillaris of diabetic patients without retinopathy investigated by swept-source OCT angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(3):50. https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.61.3.50.

Forte R, Haulani H, Jürgens I. QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE THREE CAPILLARY PLEXUSES AND CHORIOCAPILLARIS IN PATIENTS WITH TYPE 1 AND TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS WITHOUT CLINICAL SIGNS OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY: a prospective pilot study. Retina. 2020;40(2):333–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000002376.

Marques J, Marta A, Baptista PM, et al. Retinal sensitivity and structural changes after focal photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: a multisectorial comparison. Ophthalmic Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518622.

Wei X, Ting DSW, Ng WY, Khandelwal N, Agrawal R, Cheung CMG. CHOROIDAL VASCULARITY INDEX. Retina. 2017;37(6):1120–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000001312.

Agrawal R, Wei X, Goud A, Vupparaboina KK, Jana S, Chhablani J. Influence of scanning area on choroidal vascularity index measurement using optical coherence tomography. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(8):e770–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13442.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Head of the Ophthalmology Department of Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto, Prof. Dr. Pedro Menéres, for the support granted for this study.

Funding

The study received no funding, and it is the authors own work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first four authors were responsible for designing the study, analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. The fifth and sixth author were responsible for performing the complementary exams. The last two authors are diabetic retinopathy experts that contributed with their expertise and reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate and for publication

The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and its was approved by our institutional review board and ethics committee—Departamento de Ensino, Formação e Investigação do Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto ID 144-20 (114-DEFI/116-CE). The need for written informed consent was waived due to total anonymization and confidentiality of the data and the absence of detailed individual clinical information. All exams performed were considered non-invasive and performed in routine clinical setting.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Detailed imaging protocol.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Marques, J.H., Marta, A., Castro, C. et al. Choroidal changes and associations with visual acuity in diabetic patients. Int J Retin Vitr 8, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-021-00355-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-021-00355-z