Abstract

Purpose

Maxillary bone grafts and implantations have increased over recent years despite a lack of maxillary bone quality and quantity. The number of patients referred for oroantral fistula (OAF) due to implant or bone graft failure has increased, and in patients with an oroantral fistula, the pedicled buccal fat pad is viewed as a robust, reliable option. This study was conducted to document the usefulness of buccal fat pad grafts for oroantral fistula closure.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively studied 25 patients with OAF treated with a buccal fat pad graft from 2015 to 2018. Sex, age, OAF location, cause, duration, presence of systemic disease, smoking, previous dental surgery, and side effects were investigated.

Results

A total of 25 patients were studied. Mean patient age was 54.8 years, and the male to female ratio was 19:6. Causes of oroantral fistula were cyst enucleation, tumor resection, implant removal, bone graft failure, and extraction. Excellent results were obtained in 23 (92%) of the 25 patients. In the other two patients that both smoked, a small fistula was observed during follow-up. No recurrence of oroantral fistula was observed after 2 months to 1 year of follow-up.

Conclusions

The incidence of oroantral fistula is increasing due to implant and bone graft failures. Oroantral fistula closure using a pedicled buccal fat pad was found to have a high success rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oroantral fistula (OAF) is mainly caused by extraction or illness, and the treatments used to address it depend on fistula size [1, 2]. Small OAFs (< 3 mm) heal naturally over 1–2 weeks, but surgical intervention is needed for OAFs larger than 3 mm. Surgical intervention may include an advanced buccal flap and a rotational palatal flap, but a pedicled buccal fat pad (BFP) graft or skin grafts may be required for OAFs larger than 5 mm, which are often associated with an inflammatory condition [3]. Numbers of OAF patients are increasing in-line with increases in maxillary bone graft and implant placement procedures [4]. OAF closure is often attempted in local dental clinics, but not uncommon failures result in referrals. Local flaps such as an advanced buccal flap and a rotational palatal flap can be used to treat OAFs of < 5 mm, but a BFP graft is indicated when a larger flap is required for OAFs larger than 5 mm [5].

BFP graft is an established method that has been widely used since 1976 when it was first described by Egyedi [6]. Anatomically, BFP consists of four extensions of the central body, that is, buccal, pterygoid, pterygopalatine, and temporal extensions. According to reports [7, 8], closure of a defect of up to 60 × 50 × 30 mm is possible with a 6-mm-thick BFP of mean volume 10.2 ml for males and 8.9 ml for females and mean weight 9.7 g. BFP grafts fully epithelialize 6 weeks after placement, and the procedure used is straightforward and has a high success rate [9].

The purpose of this study was to document the usefulness of BFP and to identify its indications, side effects, and disadvantages by retrospectively studying the medical records of OAF patients. Furthermore, we determined the proportion of OAFs with an iatrogenic etiology and suggest means of avoiding such problems.

Materials and methods

The medical records of 25 OAF patients treated by BFP at the oral surgery department of the Dental Hospital of Pusan National University between 2015 and 2018 were reviewed retrospectively. Treatment outcomes were evaluated based on follow-up findings (Table 1). Sex, age, symptom, OAF location, cause, duration, presence of systemic disease, smoking, previous dental surgery, and side effects were investigated. Fisher exact test was undertaken in order to identify associations between different variables and post-operative complication. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the hospital and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (PNUDH-2018-042).

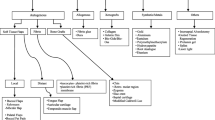

Surgery was performed by a single oral maxillofacial surgeon under general anesthesia or local anesthesia. Twenty-two cases were closed in two layers using a BFP and a buccal advancement flap (Fig. 1). In three cases, collar tape and the two-layer technique was used (Fig. 2). Patients were followed for at least 2 months. All received antibiotics for a month after surgery and were instructed on postoperative care and potential problems.

The two-layer technique using a BFP and a buccal advancement flap. a At the first visit. b Pre-operative state. c After reflection of buccal gingiva. d After suture of sinus membrane. e Buccal fat pad graft on bony defect with suture. f After advanced buccal flap suture. g 1 week post-operative state. h 2 week post-operative state

Results

Twenty-five patients of mean age 54.8 ± 13.2 years (male to female ratio 19:6) were studied. The prevalence of OAF was greatest in the fourth decade of life (32%). No patient had a specific underlying disease. OAF causes were benign tumor resection or cyst enucleation (9 cases), implant or bone graft failure (6 cases), extraction (6 cases), osteomyelitis (3 cases), and Caldwell-luc (C-L) operation (1 case). Among nine cases of benign tumor resection or cyst enucleation, six cases were prophylactic reasons. In prophylactic cases, the OAF closure operation was successful. Without those prophylactic cases, main reasons of oaf were implant or bone graft failure (31.5%) and extraction (31.5%). Three patients (12%) had a history of failed OAF closure surgery with a buccal advanced flap.

Treatment was satisfactory for all patients and BFP grafts epithelized without side effects. Best results were obtained in 23 (92%) of the 25 patients. In the remaining two cases, a small fistula occurred, but patients did not have discomfort. Both of these patients were smokers and fistulas were detected at 6 and 12 months postoperatively. In one case, healing was achieved after primary closure. In the other, small fistula was healed by itself without any surgical treatment such as primary closure. No necrosis or local inflammation was observed in any patient. Fisher exact test was undertaken in order to identify associations between different variables and post-operative complication. The results of the Fisher exact test did not show a statistically significant association with variables (Table 2).

In all patients, BFP epithelialization was complete at ~ 6 week postoperatively. No side effect such as hollow cheek or opening limitation occurred.

Discussion

A pedicled buccal fat pad flap graft was found to provide a high success rate of oroantral fistula closure in the present study, which concurs with the findings of several other studies [1, 5, 7,8,9,10]. The high success rates of BFP flaps are attributed to a rich blood supply [11, 12] from the maxillary artery (buccal and deep temporal branches), superficial temporal artery (transverse facial branch), and facial artery (small branches).

In a previous study, the main cause of OAF was tooth extraction [10], whereas in the present study, the main cause was cyst enucleation or benign tumor resection; we ascribe the difference to the fact that the present study was conducted at a university hospital. The second-most common cause was tooth extraction and the third-most was implant or bone graft failure. Interestingly, unlike previous reports, implantation and extraction contributed equally to OAF in our cohort. Implantation and bone grafting are now being widely applied, and thus, the number of patients with maxillary discomfort due to maxillary implant or bone graft failure [4, 13] and the number of oroantral fistula cases caused by implants and bone graft failures continue to increase.

Interestingly, two patients with bilateral OAF attributed to implants or bone graft failures were treated by BFP on right sides and a buccal advanced flap on left sides, because of smaller OAF sizes on left sides. Unfortunately, after a few weeks, both patients experienced left side OAF recurrence. Closure was achieved by BFP in both, and subsequently, OAF did not recur in either patient. In addition, three patients with OAF caused by implant failure experienced buccal advanced flap failure and were successfully treated by BFP. Based on these experiences, we are inclined to recommend BFP as the treatment of choice for OAF caused by implant failure, but further research is required.

The influences of the effects of age or sex on BFP volume have not been previously studied; accordingly, we advise that before a pedicled BFP flap is used for OAF closure, individual BFP volume be calculated from radiographic images (e.g., CT or MR) to assess whether coverage is possible. Also, additional studies are needed to determine the maximum volume that can be harvested based on considerations of gender, age, and individual variations.

The major limitation of the present study is that it was conducted using a retrospective design. Although all variables in medical records were carefully examined, the possibilities of inaccurate and misleading records cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, our results reveal associations and not causal relations between variables. Given that the numbers of implant and bone graft associated procedures are likely to increase further, we suggest an approach other than a buccal advanced flap and a palatal rotational flap be used to treat OAF. Despite the high success rate of BPF grafting, randomized controlled trials are needed on the topic as the amount of research performed to date is limited.

Conclusion

The present study confirms that BFP provides a comfortable and reliable means of treating OAF, which is now being treated in large numbers as a result of maxillary implant and bone graft failures. Our experiences lead us to recommend a pedicled buccal fat pad graft to treat for OAFs caused by implant failure and bone graft failure because of its high success rate.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BFP:

-

Buccal fat pad

- C-L:

-

Caldwell-luc

- CT:

-

Computerized tomography

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- OAF:

-

Oroantral fistula

References

Daif ET (2016) Long-Term Effectiveness of the Pedicled buccal fat pad in the closure of a large oroantral fistula. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 74(9):1718–1722

Hernando J, Gallego L, Junquera L, Villarreal P (2010) Oroantral communications. A retrospective analysis. Medicina Oral Patologia Oral Y Cirugia Bucal. 15(3):E499–E503

Anavi Y, Gal G, Silfen R, Calderon S, Tikva P (2003) Palatal rotation-advancement flap for delayed repair of oroantral fistula: a retrospective evaluation of 63 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med O. 96(5):527–534

Sgaramella N, Tartaro G, D’Amato S, Santagata M, Colella G (2016) Displacement of dental implants into the maxillary sinus: a retrospective study of twenty-one patients. Clin Implant Dent R. 18(1):62–72

Nezafati S, Vafaii A, Ghojazadeh M (2012) Comparison of pedicled buccal fat pad flap with buccal flap for closure of oro-antral communication. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41(5):624–628

Egyedi P (1977) Utilization of Buccal fat pad for closure of oro-antral and-or oro-nasal communications. J Maxillofac Surg. 5(4):241–244

Amin MA, Bailey BMW, Swinson B, Witherow H (2005) Use of the buccal fat pad in the reconstruction and prosthetic rehabilitation of oncological maxillary defects. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 43(2):148–154

MartinGranizo R, Naval L, Costas A, Goizueta C, Rodriguez F, Monje F et al (1997) Use of buccal fat pad to repair intraoral defects: Review of 30 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 35(2):81–84

Hanazawa Y, Itoh K, Mabashi T, Sato K (1995) Closure of oroantral communications using a pedicled buccal fat pad graft. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53(7):771–775

Jain MK, Ramesh C, Sankar K, Babu KTL (2012) Pedicled buccal fat pad in the management of oroantral fistula: a clinical study of 15 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41(8):1025–1029

Baumann A, Ewers R (2000) Application of the buccal fat pad in oral reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 58(4):389–392

Singh J, Prasad K, Lalitha RM, Ranganath K (2010) Buccal pad of fat and its applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a review of published literature (February) 2004 to (July) 2009. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 110(6):698–705

Lee KC, Lee SJ (2010) Clinical features and treatments of odontogenic sinusitis. Yonsei Med J 51(6):932–937

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was conducted with the support of 2-year Research Grant of Pusan National University, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DSH performed the conceptualization, methodology, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript. BDC, UKK, NRC, HSC collected, analyzed, and interpreted the patient data regarding oroantral fistula patient who was treated with buccal fat pad graft. JYP was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report was reviewed by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Pusan National University Dental Hospital and was approved from deliberation. (PNUDH-2018-042)

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Chun, Bd., Kim, UK. et al. Versatility of the pedicled buccal fat pad flap for the management of oroantral fistula: a retrospective study of 25 cases. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 41, 50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0229-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0229-x