Abstract

The underlying literature hypothesises and provides randomised evidence for the positive impact of promoting the broad-based inclusion, empowerment, and representation of women on regional ecosystems. This study seeks to isolate a female agency-driven development factor in external sovereign emerging market debt and finds evidence for superior risk-adjusted returns from tilting towards female agency leaders. We propose the female agency factor as an additional scope in the modern investor’s toolbox of holistic credit assessment, allowing investors to isolate the issuers which are the most effective sovereign transmission mechanisms of sustainable development capital. This contribution to the corpus supports the notion of integrating sustainability factors into portfolio construction and reinforces the argument for supporting female-led development from a financial markets’ perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inspired by the underlying literature, this paper explores the relationship between gender equality and sovereign creditworthiness in developing markets, with a focus on the potential for the promotion of female agency to support development. The problématique explores and considers whether the purported benefits of female agency-driven development are internalised by capital markets; we motivate the question: do the bonds issued by economies with a greater degree of female agency outperform those issued by economies with a lesser degree of female agency? We hypothesise that more gender-equal economies allocate resources more optimally, although we do not infer causation, reflecting on future economic development and growth—and that such a halo effect is discounted in traditional assessments of sovereign creditworthiness. As such, we expect the local capital markets of more gender-equal economies, the most effective transmission mechanisms of sustainable development capital, to outperform less gender-equal peers over time, justifying relative allocation to more gender-equal economies from the perspective of risk-adjusted financial returns.

We begin by contextualising the question and discussing the importance of female agency in developing markets, particularly as a source of sustainable development. Next, we provide an overview of our research methodology; the study approaches the problématique by seeking to isolate a female agency factor, the first known study to attempt this, by integrating a framework developed by Henide (2021) into the iBoxx USD Emerging Market Sovereigns Index ("the benchmark”) to construct factor portfolios across three key verticals (politics, economics, society) from leader and laggard portfolios. This is similar to the first-known approach for examining factors in sovereign emerging debt by Brooks et al. (2020) and the first-known approach for examining factors in emerging market credit by Dekker et al. (2021),Footnote 1 for further assessment. We conclude by summarising our findings, which support the notion that integrating sustainability risks can be a source of superior risk-adjusted returns and reinforce the argument for supporting female-led development from a financial markets perspective. The findings motivate questions for further investigation, such as whether there is a causal relationship between promoting female agency and reducing the credit risk for sovereign issuers, which has broader and deeper financial markets implications.

Contextual background

The academic literature suggests that rebalancing societies to provide women with a greater degree of inclusion, representation, and autonomy has a favourable influence on local ecosystems, both helping to prevent objectionable social activities and facilitating socially and economically-additive behaviour; the correlation between gender equality and reduced poverty in developing markets is demonstrated clearly by academics (Filmer 1999; Sinha et al. 2007; Strauss and Thomas 1995; World Bank 2001). Esther Duflo, a co-recipient of the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences,Footnote 2 also found in her seminal paper (2012) that "women’s empowerment and economic development are closely interrelated" (pp.1076).

Sowing female inclusion, equality, and empowerment into communities reaps not only rewards for the women of the community but also for men and future generations through more constructive household outcomes (Duflo 2003; Duflo and Udry 2004; Hoddinott and Haddad 1995; Pitt and Khandker 1998; Pitt et al. 2003; Rubalcava et al. 2004; Thomas 1997). This perceived halo effect has given rise to the prevalence of the gender factor in development theory and postmodernist thought; reminiscent of the aforementioned studies, Eastin and Prakash (2013) point to women's intrahousehold bargaining power and hypothesise that the opportunity of developing human capital is a vehicle for conferring greater political and social recognition, providing a rationale for the role of gender equality as a transmission mechanism for economic development, particularly amongst economies in the earlier stages of their economic development.

The bridge between improved gender equality and improved economic outcomes is encapsulated succinctly by the framework of Sinha et al. (2007), adapted in Fig. 1.

Adapted from Sinha et al. (2007)

Improving the gender balance across economies is core to improving their social and governance profile, as well as underpinning their future growth potential. The underlying framework,Footnote 3 that we integrate, references three verticals ('Politics', 'Economics' and 'Society') which derive from the pillars of equality identified in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) target 10.2. There is a comprehensive body of academic literature that justifies the pillars identified in the UN SDGs target 10.2 and the rationale behind the sustainable socioeconomic transformations achieved through the improvement of women’s social and economic outcomes' although US SDG 10.2 stipulates the inclusion of "all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status", we focus in this study only on matters pertaining to gender-based inclusion, relating to the characteristics of women and men constructed by socialisation, rather than the biological and physiological characteristics implied by "sex" (Deaux 1985). We highlight the concepts within the verticals and some key readings that attest to their significance in Table 1. The concepts are based on the framework indicators, which are a subset of the multi-source Tier 1 data ascribed in the UN Minimum Set of [Gender] Indicators (UN MSoGI).

The framework

The pillars of inclusion, equality, and empowerment

‘Politics’, ‘Economics’, and 'Society' (collectively, abbreviated to 'PES') are the three key pillars of female equality that ensure that women are free, represented, included, and empowered. They align with the spirit of UN SDG target 10.2. To capture sovereign performance across these verticals, we introduce eight concepts built upon Tier 1 data published by the World Bank under Creative Commons 4.0 licensing. The concepts and multi-source indicators are recognised by the United Nations (UN) and are upheld as key developmental indicators, contained in the UN Minimum Set of Gender Indicators.Footnote 4 Based on the UN's evaluation, we provide a mapping of each indicator to the specific strategic objectives outlined by UN Women (1995) in the Beijing Platform for Action (BPA), as well as the goals (and targets, where applicable) set out by the UN (2015) in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The categorisation of the indicators as 'Tier 1' is designated by UN Women through the curation of the Minimum Set of [Gender] Indicators. The classification confirms that the indicator 'addresses relevant issues related to gender equality and/or women's empowerment; is conceptually clear and has an internationally established methodology and standards'. Additionally, the classification confirms that the underlying data 'are regularly produced by countries, with sufficient coverage to allow tracking progress over time'.

We reproduce, in Table 2, the indicators referenced in the framework, by vertical, their mapping and the source(s) of the data. A table consisting of all project data source permalinks is available in Table 8 (appendix, Exhibit 4).

Where specified, ‘GAP’ concepts are all proprietary gender-relative derivations that seek to align scores for comparability, equilibrating for structural differences in economic infrastructure, looking specifically to assess gender (dis)parity. Concepts not labelled 'GAP' are strictly measures of absolute outcomes relating to the respective region's eligible female population subset.

The framework also references (inverse) inequality-adjusted GNI per capita, γ, defined:

where: g = Gini coefficient, GDP = Gross Domestic Product, FI = Foreign inflows, FO = Foreign outflows and;n = Population

An extensive discussion of the framework and methodology is provided by Henide (2021). All the data was accessed in November 2020. Annual data was sourced for 2010–2020, inclusive.

Equilibrating sustainability performance

Following the framework, an 'Overall PES Score' is calculated as a weighted average of the scores obtained and manipulated from the underlying data. Introducing a secondary axis, the IIGNI, provides a multi-dimensional scope for the investment universe and a counterbalance for greater comparability. In particular, the space allows investors to introduce a minimum baseline function, which provides an implied sustainability score for each vertical at each IIGNI increment. The sources for the underlying data used to construct the IIGNI are provided in Table 3.

The framework prescribes a baseline function:

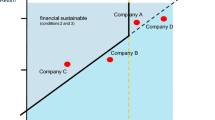

We transplant the default baseline function prescribed by Henide (2021) into our study, as illustrated by the 'baseline' in Fig. 2. The prescribed function is ideal in our setting as it exhibits goodness of fit and is progressive by nature. By inherent design, the baseline requires that countries with a higher degree of GNI per head and/or lower equality of wealth distribution (measured by the Gini coefficient) deliver higher scores in the aggregate across the 'PES' verticals to 'breakeven' with the relative performance of countries with a lower degree of GNI per head and/or higher equality of wealth distribution.

The equilibration concept and the derivation of relative performance versus the defined baseline scoring function allows investors to better compare issuers within the universe. An assessment of relative performance and the absolute 'Overall PES Score', indicates a consistent trend in scoring and relative performance, but allows us to isolate clusters of inferior issuers whose scoring is in-line with 'less wealthy' countries or those with a greater equality of wealth distribution. Conversely, we can identify countries with a superior 'Overall PES Score' performance relative to peers of a similar level of (inequality-adjusted) 'wealth'. We can also isolate clusters across the curve of sovereigns that under/outperform on an absolute level (the quadrants to the left of the universal minimum and those to the right of the universal minimum, respectively) and on a relative level (sovereigns that demonstrate a negative relative performance and those which demonstrate a positive relative performance, respectively), as highlighted inFig. 3. Footnote 5 The PES performance curve can also be used to calibrate and therefore reverse-engineer the baseline function; users may wish to 'fit' or benchmark baseline PES performance to a given set of country profiles, to which they can align the universal minimum and/or the PES performance curve.Footnote 6

Quantifying the relative performance of sovereign issuers across the key pillars of female empowerment provides us with an additional socially conscious scope with which to assess the development of developing countries and to determine portfolio capital allocation. For the purposes of our study, our focus will be solely on the relative performance of issuers.

Introducing a stratification that is progressive and relates to economic wealth overcomes some of the challenges with existing forms of ESG factor integration, such as negative exclusion based on objective ESG laggards, which contributes to a set of economic incentives that perpetuate a self-enforcing capital bifurcation cycle and entrench ESG laggards, particularly developing market countries, in a development trap (Henide 2021).

Isolating the female agency-driven development factor

Constructing long-only portfolios

We apply the framework methodology to output relative performance,Footnote 7 the difference between the actual and implied scores divided by the implied score, for the sovereign issuers represented in the iBoxx USD Emerging Markets Sovereigns Index, "the benchmark".

We construct two sets of long-only portfolios in Fig. 4. The first set consists of market-value weighted portfolios containing all of the bonds in the benchmark issued by the top quintile (Q1) of sovereign issuers based on an issuer ranking by 'performance margin' for each individual factor. Conversely, the second set consists of market-value weighted portfolios containing all of the bonds in the benchmark issued by the bottom quintile (Q5) of sovereign issuers based on an issuer ranking by 'performance margin' for the Overall PES score as well as for each individual factor.Footnote 8 In-line with the universe, issuers are re-assessed and re-ranked periodically, at every month-end rebalancing, to eliminate survivorship bias.

Deriving excess return portfolios

To better illustrate the performance of our leader and laggard portfolio sets, we calculate a cumulative log excess return relative to the cumulative log return of the benchmark in Fig. 5. We find that the portfolios of leaders have a higher cumulative log return from inception than the benchmark across the majority of months, whilst portfolios of laggards have a lower cumulative log return than the benchmark across the majority of months in the study window.

The high degree of pairwise correlation demonstrated in Table 4 may suggest some redundancy among the framework pillars and data inputs, but all elements of the framework are retained for the fullness of the assessment; the female agency framework does not look to prescribe variables that provide significance and additionality in determining asset pricing, but rather a scorecard for measuring gender equality holistically. Said differently, the selection of the pillars looks to satisfy conceptual wholeness and the prescribed pillars together constitute the definition of the female agency factor; the ‘combination’ of the factors in this context is unencumbered by multicollinearity as they otherwise would be had they been selected as independent variables in a model that sought to relate to a given dependent variable, for example. Regardless, the factors are isolated across each individual vertical for context and, as explored in the study, the high pairwise correlation is a result of, and a testament to, the regional consistency among sustainability hegemons across key female agency concepts. The co-relationship between the pillars is further illustrated in Fig. 8 (appendix, Exhibit 2) (Table 5).

The membership and respective weightings of the top and bottom quintile portfolios for the most recent month in the study and further descriptive statistics are produced in Table 6 (appendix, Exhibit 1) and Table 7 (Appendix, Exhibit 2), respectively. An additional assessment of the leader and laggard portfolios’ sensitivities to key benchmarks is also provided, in Fig. 9 (Appendix, Exhibit 3).

Deriving factor portfolios

We combine the long-only leader and laggard portfolios, by subtracting the cumulative log returns of the laggards from the cumulative log returns of the leaders (Q1–Q5), to derive factor performance in Fig. 6, deconstructing the average monthly log returns of the overall bottom and quintile portfolios in Table 5.

Triangulating leader and laggard portfolios' social and governance profile

Triangulating the academic findings that societies with a greater degree of female agency have a stronger social and political infrastructure, we introduce a dataset based on an independent methodology and sources: the Freedom House 'Global Freedom Total Scores'.

A 'Global Freedom Total Freedom Score' is a combination of a country or territory's political rights and civil liberties and is referenced as a proxy for the protection of citizens across the socioeconomic spectrum from discrimination, repression, and the infringement of their fundamental rights. We calculate the hypothetical 'Global Freedom Total Score' for the overall leader and laggard portfolios based on the portfolio constituents for each year of history (2012–2021, inclusive) and plot the results against the portfolios' hypothetical IIGNI.

Corroborating the literature, the leader portfolio consistently captured 'freer' countries, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Furthermore, the leader portfolio displayed 'stickiness' (less year-on-year variability); leader countries demonstrated hegemony across all three factors and were also likely to maintain their hegemony over time, the reverse was true for laggard portfolios.

Conclusion

In this paper, we integrate a female agency-driven development framework in the systematic construction of factor portfolios to assess whether bonds issued by economies with a greater degree of gender equality outperform those issued by economies with a lesser degree of gender equality from within the iBoxx USD Emerging Markets Sovereigns Index universe. We hypothesise that this approach to integrating sustainability considerations should contribute to financial gains for investors, from a halo effect that is otherwise discounted by traditional assessments of creditworthiness. Furthermore, we propose that the consideration of female agency-driven development widens the investor toolbox for assessing sovereign creditworthiness and allows investors to construct portfolios more optimally with respect to isolating the most effective sovereign transmission mechanisms of sustainable development capital.

Through developing factor portfolios, we find that a portfolio of issuers in the top quintile of performersFootnote 9 across either of the three verticals (Politics, Economics, Society, collectively abbreviated to 'PES') outperformed their peers in the bottom quintile of performers across each respective vertical in the long-run.

Additionally, we find that the top quintile performers across all of the verticals and over time tended to be from a narrow cluster, causing the top quintile performers to register a similar performance and demonstrate a high degree of pairwise correlation. This cluster was narrower than the laggard cluster (although laggard portfolios were also subject to a high degree of pairwise correlation). The hegemony of the top quintile of performers across time contributed to a 'stickier' portfolio and a lower cumulative portfolio turnover over the study window.

Triangulating the top and bottom quintile portfolios with Freedom House 'Global Freedom Total Scores', an external dataset with an independent methodology and data sources, we corroborate the underlying academic literature, proposing the intuition that citizens whose countries have a higher degree of female inclusion, equality, and empowerment provide a benefit to and benefit from a higher degree of political rights and civil liberties.

The findings are constructive in contextualising the behaviour of the debt issued by more gender-equal economies versus their less gender-equal peers but do not necessarily establish an explicit causal relationship between gender equality and factor outperformance. There is scope for further research to consider and establish a causal relationship for the impact of female agency on the credit risk of top quintile versus bottom quintile sovereign issuers over time.

Availability of data and materials

Derived data available on request.

Notes

Brooks et al. (2020) and Dekker et al. (2021) were preceded by factor studies in emerging market equities (Cakici et al. (2013); Hanauer and Linhart (2015); Blitz et al. (2013); Hanauer and Lauterbach (2019); Fang and Olteanu-Veerman (2020)) as well as in corporate bonds (Houweling and Van Zundert (2017); Israel et a. (2018); Henke et al. (2020); Bektić et al. (2019)).

Co-received alongside Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer, the prize was awarded for the pioneering use of randomised control trials (RCTs) in studying poverty-prevention, a sample of which trials are referenced in this study to justify the additionality of gender equality and the choice of the concepts used to assess gender equality.

The framework methodology and academic intuition are articulated in Henide, K., 2021. Assessing Developing Countries' Sovereign Creditworthiness: A Female Agency Framework. dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3896641.

Developed by the Inter-agency and Expert Group on Gender Statistics.

The annotated clusters were identified optically rather than formulaically, although clustering techniques can be leveraged to systematically identify groups of characteristically similar sovereign PES profiles. The bottom-left quadrant represents a group of absolute and relative PES underperformers, whilst the bottom-right quadrant represents a group of absolute outperformers but relative underperformers.

Users may also wish to optimise for goodness of fit, for example, by optimising the resultant R-squared, assuming model linearity.

This was calculated for each individual vertical, using the aforementioned baseline function.

We refer to Q1 and Q5 portfolios as 'leaders' and 'laggards', respectively.

'Performance' is a relative concept, derived by comparing the actual scoring of an issuer versus their implied scoring, based on their calculated 'IIGNI', a proprietary proxy for wealth, adjusted for (or, 'deflated' by) the equality of wealth distribution of the respective country, where the Gini coefficient is used as an inverse adjustment factor. Deflating the wealth of countries with a greater equality of wealth distribution is seen to be favourable as the 'baseline' against which relative performance is measured is predominantly a progressive concept; countries with a higher IIGNI often must score higher than peers with a lower IIGNI in order to 'breakeven' with their minimum scoring expectations.

Abbreviations

- BPA:

-

Beijing platform for action

- ESG:

-

Environmental, social and governance

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- GNI:

-

Gross national income

- IIGNI:

-

Inverse inequality-adjusted GNI per capita

- PES:

-

The 'Politics', 'Economics' and 'Society' verticals

- Q1:

-

Top quintile

- Q5:

-

Bottom quintile

- RCTs:

-

Randomised control trials

- UN:

-

United Nations

- UN MSoGI:

-

United Nations Minimum Set of [Gender] Indicators

- UN SDGs:

-

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

References

Afridi F (2010) Women’s empowerment and the goal of parity between the sexes in schooling in India. Popul Stud 64(2):131–145

Ashraf N (2009) Spousal control and intra-household decision making: an experimental study in the Philippines. Am Econom Rev 99(4):1245–1277

Atkinson AB (1970) On the measurement of inequality. J Econom Theory 2(3):244–263

Banerjee M (2019) Gender equality and labour force participation: mind the gap. ANTYAJAA: Indian J Women Soc Change 4(1):113–123

Bektić D, Wenzler J-S, Wegener M, Schiereck D, Spielmann T (2019) Extending Fama-French factors to corporate bond markets. J Portfolio Manag 45(3):141–158

Blitz D, Pang J, Van Vliet P (2013) The volatility effect in emerging markets. Emerg Mark Rev 16:31–45

Bolis M and Hughes C (2015) Women's economic empowerment and domestic violence: links and lessons for practitioners working with intersectional approaches

Brooks J, Richardson S, Xu Z (2020) (Systematic) investing in emerging market debt. J Fixed Income 30(2):44–61

Cakici N, Fabozzi F, Tan S (2013) Size, value, and momentum in emerging market stock returns. Emerg Mark Rev 16:46–65

Chattopadhyay R, Duflo E (2004) Women as policy makers: evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica 72(5):1409–1443

Cheston S, Kuhn L (2002) Empowering women through microfinance. Draft, Oppor Int 64:1–64

Deaux K (1985) Sex and gender. Annu Rev Psychol 36(1):49–81

Dekker L, Houweling P, Muskens F (2021) Factor investing in emerging market credits. J Beta Invest Strateg 12(2):28–46

Duflo E (2003) Grandmothers and granddaughters: old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Econom Rev 17(1):1–25

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. J Econom Lit 50(4):1051–1079

Duflo E and Udry C R (2004) Intrahousehold resource allocation in Cote d'Ivoire: social norms, separate accounts and consumption choices. NBER, Working paper 10498. https://doi.org/10.3386/w10498

Eastin J, Prakash A (2013) Economic development and gender equality: Is there a gender Kuznets curve? World Politics 65(1):156–186

Fang D, Olteanu-Veerman D (2020) The case for factor investing in China a shares. J Index Invest 11(2):76–91

Filmer D (1999) The structure of social disparities in education: gender and wealth. Policy research report on gender and development. Working paper series, No. 5

Floro M and Wolf J M (1990) The economic and social impacts of girls' primary education in developing countries. Washington, DC: USAID/AFR, The Advancing Basic Education and Literacy (ABEL) Project.

Gallaway JH, Bernasek A (2004) Literacy and women’s empowerment in Indonesia: implications for policy. J Econ Issues 38(2):519–525

Gates M (2014) Putting women and girls at the center of development. Science 345(6202):1273–1275

Goldin C, Katz LF (2002) The power of the pill: oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. J Polit Econ 110(4):730–770

Goldin C (1994) The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history (No. 4707). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Halim N, Yount KM, Cunningham SA, Pande RP (2016) Women’s political empowerment and investments in primary schooling in India. Soc Indic Res 125(3):813–851

Hanauer MX, Linhart M (2015) Size, value, and momentum in emerging market stock returns: integrated or segmented pricing? Asia Pac J Financ Stud 2:175–214

Hanauer MX, Lauterbach JG (2019) The cross-section of emerging market stock returns. Emerg Mark Rev 38:265–286

Hashemi SM, Schuler SR, Riley AP (1996) Rural credit programs and women’s empowerment in Bangladesh. World Dev 24(4):635–653

Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M (1999) Ending violence against women. Popul Rep 27(4):1–1

Henide K (2021) Assessing developing countries' sovereign creditworthiness: a female agency framework. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3896641

Henke H, Kaufmann H, Messow P, Fang-Klingler J (2020) Factor investing in credit. J Index Invest 11(1):33–51

High-Pippert A, Comer J (1998) Female empowerment: the influence of women representing women. Women Politics 19(4):53–66

Hoddinott J, Haddad L (1995) Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 57(1):77–96

Houweling P, Van Zundert J (2017) Factor investing in the corporate bond market. Financ Anal J 73(2):100–115

Hyden G (1987) Debt: the development trap. Afr Rep 32(6):24

Israel R, Palhares D, Richardson S (2018) Common factors in corporate bond returns. J Invest Manag 16(2):17–46

Kabeer N (2001) Conflicts over credit: re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Dev 29(1):63–84

Kartha S, Athanasiou T, Caney S et al (2018) Cascading biases against poorer countries. Nat Clim Chang 8(5):348–349

Krumbiegel K, Maertens M, Wollni M (2020) Can employment empower women? Female workers in the pineapple sector in Ghana. J Rural Stud 80:76–90

Lakwo A (2006) Microfinance, rural livelihoods, and women’s empowerment in Uganda (Doctoral Dissertation). Radboud University Nijmegen, Leiden, the Netherlands

LeVine R, LeVine S, Schnell B (2001) “Improve the women”: mass schooling, female literacy, and worldwide social change. Harv Educ Rev 71(1):1–51

Mocan NH and Cannonier C (2012) Empowering women through education: evidence from Sierra Leone (No. w18016). National Bureau of Economic Research

Orenstein MA (2008) Poverty, inequality, and democracy: post-communist welfare states. J Democr 19(4):80–94

Osmani LNK (2007) A breakthrough in women’s bargaining power: the impact of microcredit. J Int Develop: J Develop Stud Assoc 19(5):695–716

Pitt MM, Khandker SR (1998) The impact of group-based credit programs on poor households in Bangladesh: does the gender of participants matter? J Polit Econ 106(5):958–996

Pitt MM, Khandker SR, Chowdhury OH, Millimet DL (2003) Credit programs for the poor and the health status of children in rural Bangladesh. Int Econ Rev 44(1):87–118

Pitt MM, Khandker SR, Cartwright J (2006) Empowering women with micro finance: evidence from Bangladesh. Econ Dev Cult Change 54(4):791–831

Pitt M M, Khandker SR and World Bank, 1996. Household and intrahousehold impact of the Grameen Bank and similar targeted credit programs in Bangladesh. The World Bank

Ravallion M, Heil M, Jalan J (2000) Carbon emissions and income inequality. Oxf Econ Pap 52(4):651–669

Ross SA (1979) Disclosure regulation in financial markets: Implications of modern finance theory and signaling theory. Issues Financ Regul 5(1979):177–202

Rubalcava L, Teruel G and Thomas D (2004) Spending, saving and public transfers paid to women. UCLA CCPR population working papers

Sen A (1976) Real national income. Rev Econ Stud 43(1):19–39

Sen G, Mukherjee A (2014) No empowerment without rights, no rights without politics: gender-equality, MDGs and the post-2015 development agenda. J Human Develop Capabilities 15(2–3):188–202

Sinha N, Raju D and Morrison A (2007) Gender equality, poverty and economic growth. World Bank policy research working paper, (4349)

Strauss J, Thomas D (1995) Human resources: empirical modelling of household and family decisions. Handb Dev Econ 3:1883–2023

Swain RB, Wallentin FY (2009) Does microfinance empower women? Evidence from self-help groups in India. Int Rev Appl Econ 23(5):541–556

Thomas D (1997) Incomes, expenditures, and health outcomes: evidence on intrahousehold resource allocation. Intrahousehold resource allocation in developing countries, pp.142–64.

United Nations, 2015. United Nations sustainable development goals. United Nations

UN women, 1995. Beijing declaration and platform for action. UN Women

World Bank (2001) Engendering development: Through gender equality in rights, resources, and voice. Oxford University Press, New York

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KH (framework development, methodology, quantitative research, literature review and writing), ZA (index engineering, framework review, methodology validation, analytics processing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No conflicts of interests to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Exhibit 1

See Table 6.

Exhibit 2

Exhibit 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Henide, K., Ahmar, Z. Isolating the female agency-driven development factor in external sovereign emerging market debt. Financ Innov 9, 114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-023-00508-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-023-00508-z