Abstract

The flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) into a country can benefit both the investing entity and host government. This study employed panel analysis to examine the factors that determine the direction of FDI to the fast-growing BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and MINT (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey) countries. First, we used a pooled time-series cross sectional analysis of data from 2001 to 2011 to estimate and model the determinants of FDI for three samples: BRICS only, MINT only, and BRICS and MINT combined. Then, a fixed effects approach was employed to provide the model for BRICS and MINT combined. The results demonstrate that market size, infrastructure availability, and trade openness play the most significant roles in attracting FDI to BRICS and MINT, while the roles of availability of natural resources and institutional quality are insignificant. To sustain and promote FDI inflow, the governments of BRICS and MINT must ensure that their countries remain attractive for investment by offering a level playing field for investors and political stability. BRICS and MINT governments also need to invest more in their human capital to ensure that their economies can absorb substantial skills and technology spillovers from FDI and promote sustainable long-term economic growth. This study is significant because it contributes to the literature on determinants of FDI by extending the scope of previous studies that often focused on BRICS only.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Investment—whether public or private, domestic or foreign—is crucial to the socio-economic transformation of any economy. In the 1970s and 1980s, many developing countries imposed trade restrictions and capital controls designed to protect domestic industries from the domineering influence of their foreign counterparts and to conserve foreign exchange reserves (de Mello 1997; Dupasquier and Osakwe 2006). These policies resulted in a distortion of social and private return on capital that reduced foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into their respective countries (de Mello 1997) and impaired economic growth (Rodrik 1998). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Latin American countries responded to the challenges of economic development facing them by initiating reforms that removed restrictions on trade and FDI. These policy changes resulted in impressive economic growth by the countries in the region (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, UNESCAP 2000). Faced with shortages in domestic resources needed to finance growth, many developing countries began to look abroad for financial backing, and established policies to attract FDI (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD 2013; Asongu 2013a, 2014).

FDI in developing countries has the potential to be beneficial for both the host countries and the multi-national corporations (MNCs) or other entities seeking to invest. For the host countries, FDI provides additional financial resources through investment and by paying taxes. Foreign investment also creates employment and generates spill-over effects, such as transfer of skills and technology, managerial expertise, and corporate governance practices. At the same time, the MNCs gain access to markets, site-specific natural resources, low-cost manpower, and opportunities to exploit the advantages of bilateral and multilateral trade policies. According to the “2013 World Investment Report” published by the UNCTAD, developing countries have been receiving increasingly greater amounts of FDI, accounting for 52% of global FDI inflows in 2012. Fast-growing economies, such as Brazil, India, and China, were among the top 20 FDI recipients (UNCTAD 2013). In 2012, the highest amounts of FDI were received by Mexico in Central America, Indonesia in Southeast Asia, Nigeria in Africa, Turkey in West Asia, Brazil in South America, India in South Asia, and China in East Asia (World Bank 2013). Incidentally, these countries form the MINT and BRICS (including Russia and South Africa) countries.

BRICS is an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, a cooperative association of five major emerging or newly industrialized countries, each distinguished by a fast-growing middle class and significant influence in the regional and global economy. In 2011, the BRICS countries attracted 26% of the global FDI, contributed 15% of global GDP, and accounted for 42% of the global population (World Bank 2013). MINT is another group of fast-growing developing countries comprised of Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey. The MINT countries share a number of common features. First, they have relatively large, youthful, and growing populations as compared to the ageing and shrinking populations of many developed countries and China. Second, they are geographically well placed to take advantage of large nearby markets, with Indonesia located close to China, Turkey being contiguous to the European Union, Mexico on America’s doorstep, and Nigeria with the potential to serve as the economic hub of Africa. Of the four MINT countries, only Nigeria is not already a member of the G20 group of developed and developing countries, but it has a huge wealth of natural resources, especially oil and gas.

BRICS and MINT have substantive policies to promote the flow of FDI into their respective countries, especially to sectors that have significant multiplier effects with regard to employment and output, promotion of technology transfer, and local innovation—albeit restrictions exist in sectors considered to be strategic for national security (U.S. Department of State 2013). Between 2001 and 2012, the FDI in BRICS and MINT increased by 349%, from US$113.6 billion to US$510.4 billion (World Bank 2013). Moreover, BRICS and MINT combined attracted 30% of the global FDI, contributed 19% to the global GDP, and accounted for 51% of the global population in 2011 (World Bank 2013). Other significant statistics regarding BRICS and MINT are presented in Table 1.

This study intends to answer the question, “What are the determinants that attract FDI to BRICS and MINT countries?” Given the expanding roles played by BRICS and MINT in reshaping the global economy, and their status as destinations of choice for FDI sent to emerging economies, our empirical examination of the factors that attract FDI to these countries can provide important insights.

This research is significant because it contributes to the literature regarding the determinants of FDI by extending the scope of previous studies, many of which focused on BRICS only, such as Jadhav (2012), Jadhav and Katti (2012), and Vijayakumar et al. (2010). We examine whether the determinants of FDI in BRICS are the same as for MINT. The results of this work can provide policy direction for other fast-growing developing countries that would like to attract FDI. This paper also complements recent literature that has focused on factors determining investment in developing countries, including Bartels et al. (2009), Tuomi (2011), Kolstad and Wiig (2011), Darley (2012), Asongu (2012, 2013b, 2013c, 2015), Ajide and Raheem (2016), Xiong et al. (2015), Safaee and Geray (2017), and Pautwoe and Piabuo (2017).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Background and Related Literature” presents the theoretical basis for this research along with a review of the literature on FDI. Section “Methodology” describes the methodology employed by this study, while Section “Results and Discussions” delivers the results and a discussion. Our concluding remarks are given in Section “Conclusion”, including suggestions for the direction of future work.

Background and related literature

Theories of FDI

The existing literature distinguishes between three types of theories concerning the relationship of FDI to economic development: the dependency theory, classical theory, and middle path theory (Toone 2013; Gammoudi et al. 2016). The dependency theory builds on a Marxist foundation that perceives globalization through the prism of exploitation of cheap labor, expansion of market capitalism, and exchange of primary resources in return for obsolete technological know-how from more developed countries. Advocates of the dependency theory hold that the potentially negative influence of FDI on development outcomes in less developed countries can be substantiated as follows. (i) The rewards of FDI are not equitably distributed between host countries and multi-national corporations (MNCs) because the latter get the lion’s share of the various benefits. Moreover, by exploiting profit-making avenues in less developed countries and sending the profits to their rich home nations, foreign investors crowd out local assets that would otherwise have been utilized to fund local development (Jensen 2008). (ii) MNCs also create instability in domestic economies by distorting domestic investment. MNCs use capital-intensive technologies that increase unemployment, increase income-inequality, and change the tastes of customers by undermining local values (Taylor and Thrift 2013). (iii) Often, the citizens of the under-developed host countries are excluded from reaping the fruits of FDI because of alliances between the local politico-economic elite and foreign investors (Jensen 2008).

In contrast, proponents of the classical theory maintain that FDI can be beneficial to the domestic economies of less developed countries through a number of mechanisms: improvement in the balance of payments; transfer of capital, skills, and advanced technologies; growth of foreign exchange earnings; expansion of the tax base resulting from exports related to FDI; integration of the domestic economy into international markets; and development of domestic infrastructure (Toone 2013). The literature on FDI spillovers, which has been documented substantially, provides insight that spillover effects take many forms, including better working methods, good management skills, more employment, domestic financial development, and higher productivity gains (Javorcik 2004; Asongu and De Moor 2017).

The “middle path” theory is a combination of the two preceding theoretical approaches. In essence, the middle path is a cautious theory that focuses on the development consequences of foreign direct investment. Dependency theory focuses on the obvious negative effects from FDI, while classical theory points out the rewards, especially if initial conditions needed for the benefits of FDI are satisfied by the developing domestic economies (Asongu 2017a; Gammoudi et al. 2016). Proponents of the middle path seek the convergence of these theories by emphasizing the importance of a mixture of regulation (i.e., intervention) and openness. This combined approach addresses both the cautions presented by dependency theory that require heavy government intervention and regulation, and the rewards described by classical theory’s advocacy of openness. In a nutshell, according to the middle path, the goal of the domestic economy is to attract FDI while adopting policies that reduce the negative effects of FDI.

There are fundamental determinants of FDI that are acknowledged by all of the versions of the contending theories, notably policy indicators (e.g., tax, trade, privatization, and macroeconomic policies), business dynamics (e.g., incentives for investment), market-related factors (e.g., market structure, market growth, and market size), resource-oriented determinants (e.g., technology availability, labor costs, and raw materials), and drivers toward economic efficiency (e.g., labor productivity, and transportation and communication costs). Our study builds on these common denominators to assess FDI determinants in the fast-growing economies in the BRICS and MINT countries. This approach allows us to examine the motivations of MNCs when deciding to adopt locations for their FDI efforts.

Over the years, the motivations of multi-national enterprises for engaging in FDI have been rationalized from several theoretical viewpoints, including neoclassical trade theory, market imperfections, product lifecycle theory, and eclectic paradigms. Neoclassical trade theory builds on the Heskscher-Ohlin model, which asserts that trade opportunities and capital flows between two countries depend on the relative endowment of factors of production. The implication is that multi-national enterprises invest in countries to take advantage of higher returns on investment or low production costs. In comparison, the market imperfection theory argues that because markets are imperfect, multi-national enterprises are able to locate their businesses or production activities in these countries to exploit economies of scale, ownership advantages, and government incentives (Kindlerberger 1969; Eiteman et al. 2007). Furthermore, the theory asserts that market imperfections in underdeveloped countries propel multi-national enterprises to internalize their operations in those host countries as the most economical means of safeguarding their intangible assets (Buckley and Casson 1976; Hennart 1982; Shapiro 2006).

The product lifecycle theory developed by Vernon (1966) asserts that the lifecycle of a product has four stages: introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. Furthermore, lifecycle development follows a pattern, whereby new products are introduced first in advanced countries and then diffused over time to developing countries. Therefore, the stages of the product lifecycle influence the decision of a multi-national enterprise either to export the product or set up a production facility in the foreign market. The goal of the MNC is to achieve lower production costs while catering to the growing demand for its product in both the foreign market and the home market at a competitive price. Finally, the eclectic paradigm, developed by Dunning (1988, 1993, 2000) is perhaps the most comprehensive theoretical viewpoint for rationalizing the decisions of multi-national enterprises to engage in FDI. The eclectic paradigm framework holds that the scope, geography, and industrial components of FDI by multi-national enterprises are influenced by the interaction of three sets of interdependent variables. These variables are themselves composed of the sub-components of three areas of focus: strategic advantages in ownership, location specificity, and internalization (OLI).

Review of related literature

A substantial number of empirical studies have explored the determinants of FDI in developing countries. Studies that focused on a single country often used time-series analysis, while multi-country studies often employed panel data analysis (Asiedu 2002; Biswas 2002; Jadhav 2012; and Rogmans & Ebbers, 2013). The choice of dependent as well as explanatory variables also differed depending on the countries examined. For the dependent variables, studies used the unidirectional FDI inflow to host countries (Rogmans & Ebbers, 2013), net FDI inflow (Jadhav 2012), ratio of FDI inflow to GDP (Suliman and Mollick 2009; Lehnert et al. 2013), and ratio of net FDI flows to GDP (Asiedu 2002). The choice of explanatory variables varied as well, although some variables have been used consistently. For instance, market size (often represented by real GDP or real GDP per capita) was employed by many empirical studies (Cheng and Kwan 2000; Moosa and Cardak 2006) because it captures the demand for goods and services in the host country. Other explanatory variables often used include the level of trade openness, growth rate, an indicator for infrastructure availability, inflation, and availability of natural resources, as well as indicators that capture political risk and institutional strength (Asiedu 2002; Moosa 2002; Moosa and Cardak 2006; Jadhav 2012; Sichei and Kinyondo 2012; Rogmans & Ebbers, 2013). UNCTAD (2002) classifies these variables into the five major groups shown in Table 2. Nontraditional variables such as type of regime in the host country (e.g., democracy, autocracy, monarchy), regime duration, and risk of expropriation of private investment have also been used in some studies (Biswas 2002).

Jadhav (2012) explored the role of economic, institutional, and political factors in attracting FDI to BRICS economies using panel data for the ten-year period 2000–2009. The findings of the study indicated that the market size, openness to trade, and rule of law played significant roles in attracting FDI to BRICS, while natural resource availability had a negative impact, implying that FDI in BRICS is largely market-oriented. Jadhav and Katti (2012) observed that effective governance and regulatory quality had a positive impact on FDI inflow in BRICS, while political instability, voice and accountability, and control of corruption had negative effects. Similarly, using data from 1975 to 2007, Vijayakumar et al. (2010) employed panel analysis to examine the determinants that bring FDI to BRICS. They observed that market size, labor cost, infrastructure, and gross capital formation contributed positively to FDI inflow, while the effects of trade openness and inflation were insignificant.

Asiedu (2002) examined the determinants of FDI in developing countries with special focus on Africa. Building on the observation that developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) attracted very little FDI in the 1990s despite economic reforms, the study sought to understand whether the determinants of FDI in developing countries in other regions were different from those in SSA. They employed panel data for 71 developing countries for the years 1988–1997. The results showed that low infrastructure development and low return on capital, as well as the unfavorable geographic location of many SSA countries, were responsible for the limited FDI inflow. Similarly, Asiedu (2005) examined the role of natural resources, market size, government policy, institutions, and political instability in attracting FDI to countries in SSA.

Rogmans and Ebbers (2013) examined the determinants of FDI in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region using panel data from 1987 to 2008. They observed that natural resources endowment contributed negatively to FDI inflows while trade openness had a positive effect. The study suggested that the negative contribution of natural resource endowment to FDI resulted because countries that are highly endowed are more likely to have protectionist policies, thereby limiting potential FDI from resource-seeking MNCs. Hayakawa et al. (2013) investigated the effects of various components of political and financial risk on FDI inflow using panel data for 89 developing countries for the period 1985–2007. They observed that internal conflict, military politics, corruption, and bureaucracy influenced FDI flow negatively, while lower financial risk had no significant impact. Cleeve (2012) used panel data to examine the role of several institutional factors and political stability in attracting FDI to 40 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition to institutional variables included in many other previous studies, Cleeve’s study considered ethnic tensions, religious tensions, and disaggregated conflicts when examining internal and external factors.

A summary of results from earlier studies that examined the determinants of FDI can be found in Asiedu (2002), Moosa (2002), and Moosa and Cardak (2006). Other studies that explored the determinants of FDI include Sekkat and Veganzones-Varoudakis (2007), Ranjan and Agrawal (2011), and Buchanan et al. (2012). Rjoub et al. (2017a) investigated the impact of FDI inflows on economic growth in landlocked countries in Sub-Saharan Africa to establish a positive nexus between the two variables. Rjoub et al. (2016) assessed the connection between FDI and economic growth in Latin American countries to document that economic growth is affected positively by FDI inflows.

Methodology

Data and variables

Following the practice of previous studies, this paper adopted a panel analysis procedure to examine data for the eleven-year period 2001–2011. The sample was limited to BRICS and MINT countries because they were recognized as fast-growing emerging economies at the time of the study. The periodicity also was 2001–2011 because of data availability constraints at the time of the study. Appendix 1 reports improvements of GDP per capita with manufacturing and industrial activities in the MINT and BRICS countries for almost the same periodicity (Asongu and Odhiambo 2018). As apparent from the table, the highest GDP growth per capita occurred in China, India, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Turkey while the highest increase per year during the corresponding time period occurred, in increasing order, in India, South Africa, Brazil, China, and Turkey.

The choice of variables used in our model was influenced by previous studies as well. For the dependent variable, we used the net FDI inflow (Jadhav 2012) expressed in billion US$, as denoted by NetFDI. This value was log-normalized to enable comparability with other variables. As noted by UNCTAD (2002), determinants of FDI may be market-related, resource-related, efficiency-related, or related to sound economic and/or political policies. In addition, indicators for institutional and governance quality were used as explanatory variables (Jadhav 2012, Jadhav and Katti 2012; and others) because they impact investment risk in fast-growing economies, which in turn affects the attractiveness of the country for FDI. In summary, our explanatory variables are shown below.

-

(1)

GDP: The gross domestic product given in terms of constant 2005 U.S. dollars (in billions)—used as a proxy for market size, i.e., GDP is a market-related economic determinant.

-

(2)

NResGDP: The share of natural resources in GDP expressed in percentages—used as a proxy for resource-related economic determinants.

-

(3)

Infrastructure: An indicator of the level of infrastructure availability, expressed in terms of the number of mobile phones per 100 persons (Asiedu 2002; Sekkat and Veganzones-Varoudakis 2007)—used as a proxy for efficiency-related economic determinants.

-

(4)

Inflation: The inflation rate (consumer price index) of a country—used as a proxy for macro-economic stability.

-

(5)

Trade: Representing openness to trade i.e., the ratio of total trade (exports + imports) to GDP—used as a policy variable.

Data used in the study were obtained from the World Bank’s databases for world development indicators and world governance indicators.

Principal component analysis of governance and institutional indicators

The indicators for institutional and governance quality capture different broad dimensions of the character of institutions and administration of a country. This approach implies that including all of the indicators as explanatory variables in a model has the potential to increase the model’s explanatory powers. However, because these variables capture different dimensions of governance, there is a strong likelihood that they would be highly correlated. Consequently, a model that includes all the indictors would likely suffer from multicollinearity. The matrix of pair-wise correlation coefficients of the variables as shown in Table 3 confirms this suspicion, demonstrating that the correlations between all pairs of indicators are significant. Moreover, including all the variables could lead to over-parameterization of the model, which would affect the reliability of the model. Therefore, this study used principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimension of the variables.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a statistical technique applied to reduce the dimensionality of a larger set of possibly correlated variables into a smaller set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components. The first principal component accounts for the largest possible variance from the original data set, and each successive principal component accounts for a variance smaller than that of the preceding principal component (Jolliffe 2002). We employed Eviews to calculate the PCA for the governance and institutional indicators using ordinary correlations. The summary of our results presented in Table 4 shows that the first eigenvalue encompassed up to 75% of the information on institutional and governance indicators. Therefore, the corresponding eigen vector (i.e., the eigenvector for PC 1) was selected to compute the principal component from the institutional and governance indicators. A correlation matrix involving all of the variables is provided in Appendix 3.

Model specification

We specify our model as follows:

where i represents the i th country, and t represents the year.

We expected, a priori, that the coefficient of the GDP would be positive since market size was anticipated to have a positive influence on FDI inflow. Although natural resources availability in developing countries can attract resource-seeking FDI, previous studies have argued that resource-seeking FDI in resource-rich developing countries depends on existing investment policies and market orientation (Rogmans & Ebbers, 2013). In some studies, the availability of natural resources contributed positively to FDI (Asiedu 2005; Sichei and Kinyondo 2012), while in others, it contributed negatively (Jadhav 2012; Rogmans & Ebbers, 2013). Therefore, the expected sign of the coefficient of NResGDP was not certain.

The availability of good infrastructure reduces transaction costs. Therefore, we anticipated that the coefficient of Infrastructure would be positive. The coefficient of Trade was expected to be positive because countries that are more open to trade tend to attract market-seeking FDI, while the coefficient of Inflation was predicted to be negative because a low and stable inflation rate reduces the macroeconomic risks associated with investment and makes the host country more attractive to FDI. Furthermore, high political risks and inefficient institutions generally discourage FDI (Asiedu 2005; Dupasquier and Osakwe 2006), so InstIndex was expected to have a positive coefficient. The analysis was done using Eviews.

Results and discussions

We present the descriptive statistics for BRICS and MINT in Table 5. We observe from Table 5 that the net FDI inflow to BRICS between 2001 and 2011 ranged from US$-0.18 billion to US$280.07 billion, with an average of US$43.15 billion and a standard deviation of US$58.05 billion. Similarly, the maximum and minimum GDP were US$4194.94 billion and US$210.30 billion, respectively, while the mean and standard deviation were US$1119.96 billion and US$922.76 billion, respectively. For the institutional index, the maximum and minimum values were 1.71 and − 2.12, respectively, while the mean and standard deviation were − 0.11 and 0.82, respectively. However, the maximum and minimum net FDI inflows to MINT for the years under consideration were US31.38 billion and US$-2.98 billion, respectively, with a mean of US$11.26 billion and standard deviation of US$9.41 billion. The Institutional index for MINT ranged from − 3.08 to 0.13, with a mean of − 1.20 and standard deviation of 1.12. Table 6 provides the full summary of the statistics for the BRICS and MINT countries, including the units of measurement.

To examine whether the determinants of FDI in BRICS are different from those of MINT, we employed the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) pooled time-series cross-sectional technique to calculate Eq. (1) for three subsamples: BRICS only, MINT only, and BRICS and MINT combined. Pooled analysis was preferred over panel analysis for the BRICS only and MINT only subsamples because panel analysis would involve testing whether the model follows a fixed effect model or random effect model, and random effects estimation requires the number of cross sections to be greater than the number of coefficients. The results of the pooled analysis are presented in Table 6.

Table 6 demonstrates that GDP was a significant determinant of FDI in both BRICS and MINT countries. The coefficient of NResGDP was positive and insignificant in the subsample of BRICS only, but negative and insignificant in the subsample of MINT only. The coefficient of infrastructure was positive and significant in BRICS, but not significant in MINT. For Inflation, the coefficient was negative in MINT as expected, although insignificant but positive in BRICS. The coefficient of Trade was negative and insignificant in BRICS, but positive and significant in MINT, while the coefficient of InstIndex was positive and significant in BRICS as expected, but negative in MINT. Thus, we observe that depending on the set of countries considered, the determinants of FDI in fast-growing developing economies differed. For the combined sample of MINT and BRICS as estimated using OLS, the signs of the coefficients of GDP, Infrastructure, and Trade were in line with our a priori expectations and were significant, suggesting that these are the main determinants of FDI in BRICS and MINT.

We went further to ascertain the appropriate specification (i.e., fixed-effect or random-effect) to use in estimating the model for the combined sample of BRICS and MINT. We carried out the Hausman specification test (Hausman 1978) under the null hypothesis that the individual effects are uncorrelated with the other regressors in the model (i.e., estimates from the random-effect model are consistent and efficient). The p-values (0.0000) of the chi-square value (35.06) from the Hausman specification test for cross-section random effect were less than 0.05, indicating that the null hypothesis can be rejected. Consequently, the fixed effect model specification was employed to estimate the panel model. A summary of the results is presented in Table 7.

Consistent with recent literature, the fixed effects model was adopted to control for country-specific features or unobserved heterogeneity, which is related to endogeneity. Furthermore, according to Asongu (2016) and Asongu and Nwachukwu (2018), when a panel consists of observations of fixed and comparatively small sets of cross section units (e.g., member states of a given region), there is a presumption in favor of FE.

We observe from Table 7 that the coefficient of GDP was positive as expected and significant, indicating that market size was an important determinant of FDI inflows to BRICS and MINT. This finding implies that, ceteris paribus, if the GDP of BRICS and MINT were to increase by US$1 billion, on average, the amount of FDI directed into the countries would increase by US$56 million. The sign of NResGDP was negative but insignificant, indicating that BRICS and MINT countries that are less dependent on natural resources are likely to receive more FDI. This result also suggests that FDI flows into BRICS and MINT are not resource-oriented but market-oriented. The sign of the coefficient of Infrastructure was in line with a priori expectations and was significant. This finding suggests that for every unit increase in the number of mobile phones users per 100 persons in BRICS and MINT, on average, FDI inflow to the countries will increase by $US156 million, all other things being equal. This result further emphasizes the importance of infrastructure in reducing the cost of transacting business in a country, thereby encouraging investment.

The study expected the coefficient of Inflation to be negative, but the result yielded a positive and insignificant coefficient. One possible explanation is that BRICS and MINT countries that have higher inflation rates tend to attract more FDI. A more plausible interpretation is that macro-economic stability in BRICS and MINT tends to play a lesser role in investment decisions by multi-national corporations. The coefficient of Trade was positive as expected and significant, indicating that countries that are more open to trade are more likely to attract greater amounts of FDI. The coefficient of the InstIndex was partially negative. This finding suggests from an institutional perspective that MNCs are more likely to invest in BRICS than MINT countries.

Conclusion

The roles of BRICS and MINT countries in reshaping the global economic environment should not be underestimated. In 2011, BRICS and MINT together accounted for 51% of the global population, attracted 30% of global FDI, and contributed 19% of global GDP. Based on these facts, this study set out to examine the factors that determine the flow of FDI to BRICS and MINT. We observed that market size, infrastructure availability, and trade openness play the most significant roles in attracting FDI to these countries, while natural resources availability and institutional quality play insignificant roles. Given that FDI inflow to a country has the potential of being mutually beneficial to the investing entity and host government, the challenge is to ascertain how BRICS and MINT can sustain their respective levels of FDI inflows and achieve resulting economic growth and socio-economic transformation.

To sustain the level of FDI inflow, the governments of BRICS and MINT need to ensure that their countries remain attractive for investment. This implies that in addition to offering large-scale markets and strategic geographical locations, these countries need to guarantee that the existing legal framework for investment protects investors and creates a level playing field for competition in the domestic market. BRICS and MINT governments also need to ensure political stability in their countries, as stability will reduce investment risk. The governments of countries with relatively low level or inefficient infrastructures, especially for transportation and energy (e.g., India and Nigeria) need to invest more in these sectors.

The following recommendations are offered to address the limitations of the current study. Future research should use other empirical strategies to assess whether the established relationships can withstand empirical scrutiny from country-specific points of view. Such country-oriented frameworks are necessary for identifying more targeted policy implications. Adding human capital to the information set also be worthwhile as well. Human capital is relevant in economic development because research and education have a multitude of direct and indirect positive impacts on real production per capita as well as on socio-economic welfare. Government quality, the empowerment of women, and a large number of other indicators can be used for this purpose. The importance of considering human capital is supported by recent international literature regarding development, including the work of Guisan and Neira (2006), Guisan (2009, 2015), Asongu and Tchamyou (2018), Asongu 2017b), and Tchamyou (2017, 2018).

Abbreviations

- BRICS:

-

Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

- CC:

-

Corruption Control

- FDI:

-

Foreign Direct Investment

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- GE:

-

Governance Effectiveness

- InstIndex:

-

The first principal component of six governance and institutional-related indicators

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

- MINT:

-

Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey

- MNC:

-

Multi-national company

- OLI:

-

Ownership, location specificity, and internalization

- PC:

-

Principal Component

- PCA:

-

Principal Component Analysis

- PS:

-

Political Stability

- RL:

-

Rule of Law

- RQ:

-

Regulation Quality

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UNCTAD:

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

- UNESCAP:

-

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

- VA:

-

Voice and Accountability

References

Ajide KB, Raheem ID (2016) Institutions-FDI Nexus in ECOWAS Countries. J African Bus 17(3):319–341

Asiedu E (2002) On the determinants of foreign direct investment to developing countries: is Africa different? World Dev 30(1):107–119

Asiedu E (2005) Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: The Role of Natural Resources, Market Size, Government Policy, Institutions and Political Instability. Working paper, United Nations University, Helsinki.

Asongu SA (2012) Government quality determinants of stock market performance in African countries. J Afr Bus 13(3):183–199

Asongu SA (2013a) Investment and inequality in Africa: which financial channels are good for the poor? African Finance J 12(2):43–65

Asongu SA (2013b) African stock market performance dynamics: a multidimensional convergence assessment. J Afr Bus 14(3):186–201

Asongu SA (2013c) How would population growth affect investment in the future? Asymmetric panel causality evidence for Africa. Afr Dev Rev 25(1):14–29

Asongu SA (2014) Financial development dynamic thresholds of financial globalization: evidence from Africa. J Econ Stud 41(2):166–195

Asongu SA (2015) Long-term effects of population growth on aggregate investment dynamics: selected country evidence for Africa. Afr J Econ Manag Stud 63(1):225–250

Asongu SA (2016) Drivers of growth in fast developing countries: evidence from bundling and unbundling institutions. Polit Policy 44(1):97–134

Asongu SA (2017a) Assessing marginal, threshold and net effects of financial globalisation on financial development in Africa. J Multinational Financ Manag 40:103–114

Asongu SA (2017b) Knowledge Economy Gaps, Policy Syndromes, and Catch-Up Strategies: Fresh South Korean Lessons to Africa. J Knowl Econ 8(1):211–253

Asongu SA, De Moor L (2017) Financial globalisation dynamic thresholds for financial development: evidence from Africa. Eur J Dev Res 29(1):192–212

Asongu SA, Nwachukwu JC (2018) Educational quality thresholds in the diffusion of knowledge with mobile phones for inclusive human development in sub-Saharan Africa. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 129:164–172

Asongu SA, Odhiambo NB (2018) Drivers of growth in fast emerging economies: a dynamic instrumental quantile approach to real output and its rates of growth in Brics and Mint countries, 2001-2011. Appl Econ Int Dev 18(1):5–22

Asongu SA, Tchamyou VS (2018) Human capital, knowledge creation, knowledge diffusion, institutions and economic incentives: South Korea versus Africa. Contemp Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1457170

Bartels FL, Alladina SN, Lederer S (2009) Foreign direct Investment in sub-Saharan Africa: motivating factors and policy issues. J Afr Bus 10(2):141–162

Biswas R (2002) Determinants of foreign direct investment. Rev Dev Econ 6(3):492–504

Buchanan BG, Le QV, Rishi M (2012) Foreign direct investment and institutional quality: some empirical evidence. Int Rev Financ Anal 21(C):81–89

Buckley P, Casson M (1976) The future of the multinational Enterprise. Homes & Meier, London

Cheng L, Kwan Y (2000) What are the determinants of the location of foreign direct investment? The Chinese experience. J Int Econ 51(2):379–400

Cleeve E (2012) Political and institutional impediments to foreign direct investment inflows to sub-Saharan Africa. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev 54(4):469–477

Darley WK (2012) Increasing sub-Saharan Africa’s share of foreign direct investment: public policy challenges, strategies and implications. J Afr Bus 13(1):62–69

de Mello LR (1997) Foreign direct investment in developing countries and growth: a selective survey. J Dev Stud 34(1):1–34

Dunning JH (1988) Explaining international production. Unwin Hyman, London

Dunning JH (1993) Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Addison Wesley, Wokingham

Dunning JH (2000) The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. Int Bus Rev 9(2):163–190

Dupasquier C, Osakwe PN (2006) Foreign direct investment in Africa: performance challenges, and responsibilities. J Asian Econ 17(2):241–260

Eiteman DK, Stinehill AI, Moffett MH (2007) Multinational business finance, 11th edn. Pearson Addison Wesley, Boston

Gammoudi M, Cherif M, Asongu SA (2016) FDI and growth in the MENA countries: are the GCC countries different? African Governance and Development Institute WP/16/015, Yaoundé

Guisan MC (2009) Quality of government, education and world development: an analysis of 132 countries, 2000-2007. Int J Appl Econ Quant Stud 6(2):5–30

Guisan MC (2015) Selected readings on econometrics methodology, 2001-2010: causality, measure of variables, dynamic models and economic approaches to growth and development. Appl Econ Int Dev 15(2):213–220

Guisan MC (2017a) Manufacturing and Development in Countries and Areas of Africa, 2000–2010. Reg Sect Econ Stud 17(2):137–148

Guisan MC (2017b) Manufacturing and Development in Countries and Areas of Europe and Eurasia, 2000–2010. Reg Sect Econ Stud 17(1):129–148

Guisan MC, Aguayo E (2015) Manufacturing and development in countries and areas of America, 2000-2010. Reg Sect Econ Stud 15(1):187–193

Guisan MC, Exposito P (2015) Manufacturing and development in countries and areas of Asia-Pacific, 2000-2010. Reg Sect Econ Stud 15(2):203–208

Guisan MC, Neira I (2006) Direct and indirect effects of human capital on world development, 1960-2004. Appl Econ Int Dev 6(1):17–34

Hausman J (1978) Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica 46(6):1251–1271

Hayakawa K, Kimura F, Lee H-H (2013) How does country risk matter for foreign direct investment? Dev Econ 51(1):60–78

Hennart J (1982) A theory of multinational enterprise. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Jadhav P (2012) Determinants of foreign direct investments in BRICS economies: analysis of economic, institutional and political factors. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 37(2012):5–14

Jadhav P, Katti V (2012) Institutional and political determinants of foreign direct investment: evidence from BRICS economies. Poverty Public Policy 4(3):49–57

Javorcik BS (2004) Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. Am Econ Rev 94(3):605–627

Jensen NM (2008) Nation-states and the multinational corporation: a political economy of foreign direct investment. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Jolliffe I (2002) Principal component analysis, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Kindlerberger C (1969) American business abroad: six lectures on direct investment. Yale University Press, New Haven

Kolstad I, Wiig A (2011) Better the devil you know? Chinese foreign direct Investment in Africa. J Afr Bus 12(2):31–50

Lehnert K, Benmamoun M, Zhao H (2013) FDI inflow and human development: analysis of FDI’s impact on host countries’ social welfare and infrastructure. Thunderbird Int Business Rev 55(3):285–298

Moosa I (2002) Foreign direct investment: theory, evidence and practice. Palgrave, London

Moosa IA, Cardak BA (2006) The determinants of foreign direct investment: an extreme bounds analysis. J Multinational Financ Manag 16(2):199–211

Pautwoe JT, Piabuo T (2017) Financial sector development and economic growth: evidence from Cameroon. Financ Innov. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-017-0073-x

Ranjan V, Agrawal G (2011) FDI inflow determinants in BRIC countries: a panel data analysis. Int Bus Res 4(4):225–263

Rjoub H, Aga M, Oppong C, Sunju N, Fofack A (2017a) The Impact of FDI Inflows on Economic Growth: Evidence from Landlocked Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Bilig - Turk DunyasI Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi X(1):153–168

Rjoub H, Alrub AA, Soyer K, Hamdan S (2016) The syndrome of FDI and economic growth: evidence from Latin American countries. J Financ Stud Res 2016:542185

Rjoub H, Civcir I, Resatoglu NG (2017b) Micro and Macroeconomic Determinants of Stock Prices: The Case of Turkish Banking Sector. Rom J Econ Forecast XX(1):150–166

Rodrik D (1998) Trade policy and economic performance in sub-Saharan Africa. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 6562, Cambridge.

Rogmans T, Ebbers H (2013) The determinants of foreign direct investment in the Middle East North Africa region. Int J Emerg Markets 8(3):240–257.

Safaee M, Geray MS (2017) Family control and corporate social responsibility: evidence from Iranian companies. Int J Financ Eng 4(4):1–13

Sekkat K, Veganzones-Varoudakis M-A (2007) Openness, investment climate, and FDI in developing countries. Rev Dev Econ 11(4):607–620

Shapiro CA (2006) Multinational Financial Management, 8th edn. Wiley, United States of America

Sichei MM, Kinyondo G (2012) Determinants of foreign direct Investment in Africa: a panel data analysis. Glob J Manag Bus Res 12(18):85–97

Suliman AH, Mollick VA (2009) Human capital development, war and foreign direct Investment in sub-Saharan Africa. Oxf Dev Stud 13(1):47–61

Taylor M, Thrift N (2013) The geography of multinationals: studies in the spatial development and economic consequences of multinational corporations. Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames.

Tchamyou VS (2017) The role of knowledge economy in African business. J Knowl Econ 8(4):1189–1228

Tchamyou VS (2018) Education, lifelong learning, inequality and financial access: evidence from African countries. Contemp Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1433314

Toone JE (2013) Mirage in the Gulf?: Examining the Upsurge in FDI in the GCC and Its Legal and Economic Implications for the MENA Region (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2150603). Social Science Research Network, Rochester

Tuomi K (2011) The role of the investment climate and tax incentives in the foreign direct investment decision: evidence from South Africa. J Afr Bus 12(1):133–147

UNCTAD (2002) World investment report: transnational corporations and export competitiveness. United Nations, New York

UNCTAD. (2013). World Investment Report 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013, From United Nations conference on trade and development: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2013_en.pdf

UNDP. (2013). Human Development Reports. Retrieved January 26, 2014, from United Nations Development Programme: http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/2013GlobalHDR/English/HDR2013%20Report%20English.pdf

UNESCAP. (2000). Foreign Direct Investments in Latin America: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Retrieved December 11, 2013, from United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific: http://www.unescap.org/tid/publication/tipub2069.pdf

US Department of State. (2013). Investment Climate Statements 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2014, From http://www.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/2013/

Vernon R (1966) International investment and international trade in the product cycle. Q J Econ 80(2):190–207

Vijayakumar N, Sridharan P, Rao KC (2010) Determinants of FDI in BRICS countries: a panel analysis. Int J Bus Sci Appl Manag 5(3):1–13

World Bank. (2013). World Development Indicators. UK Data Service. Retrieved January 23, 2014, from World Bank.

Xiong X, Yuan H, Zhang W, Zhang Y (2015) Program trading and its risk analysis based on agent-based computational finance. Int J Financ Eng 2(2):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2424786315500140.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the editor and reviewers for constructive comments.

Funding

This is an unfunded paper.

Availability of data and materials

The data for this paper is available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SAA participated in the writing of the manuscript and data analysis. USA participated in the writing of the manuscript and data analysis. SRI participated in the writing of the manuscript and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

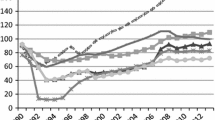

The evolution of real value-added per capita of Manufacturing and Non-manufacturing activities, as well of real Gross Domestic Product per capita of BRICS and MINT countries for the period 2000–2010. Figure 1 shows the average annual increase of real production per head for the period 2000–2010.

Increase of real GDP per capita for the period 2000–2010. Source: Elaborated with data of GDPH from Appendix 1. Countries: 1. Brazil, 2. China, 3. India, 4. Indonesia, 5. Mexico, 6. Nigeria, 7. Russia, 8. South Africa, 9. Turkey

It is apparent from Appendix 1 that the order of the countries is not the same if we use the highest positive variations or the highest rates of growth, because for a same increase a lower initial value implies faster growth (higher rate of growth). The highest rates of growth of per head corresponded to China, India, Nigeria, Indonesia and Turkey, but the highest increases, of real GDP per capita, per year corresponded, in descending order, to Turkey, China, Brazil, South Africa and India (Asongu and Odhiambo 2018).

Appendix 2

These definitions of the indicators of governance and institutional quality are obtained from the World Governance Indicators database of the World Bank.

-

(i).

Voice and accountability - reflects perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media.

-

(ii).

Political Stability/ No violence - reflects perceptions of the likelihood that the government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means, including politically-motivated violence and terrorism.

-

(iii).

Governance effectiveness - reflects perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies.

-

(iv).

Regulatory quality - reflects perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development.

-

(v).

Rule of Law - reflects perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence.

-

(vi).

Control of Corruption - reflects perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests.

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Asongu, S., Akpan, U.S. & Isihak, S.R. Determinants of foreign direct investment in fast-growing economies: evidence from the BRICS and MINT countries. Financ Innov 4, 26 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-018-0114-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-018-0114-0