Abstract

Background

Long acting and permanent contraceptives methods are more effective, save cost and enable women to control their reproductive lives better. Although the Ethiopian government is promoting its use through various mechanisms, the level of use is low. Therefore, this study was designed to identify factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use in Ethiopia.

Methods

Four Ethiopian demographic and health survey data were used to examine trends of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use. To identify factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use, the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data was used. The data was accessed from the demographic and health survey program data base. Data analysis was done using Stata 15.1. Descriptive analysis was used to describe socio-economic and other variables of the study participants. Data were weighted and design effect was considered during analysis. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factor. Finally, multinomial logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use.

Results

Long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use increased significantly from 0.6% in 2000 to 11.6% in 2016. The odds of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use was higher among richer women (AOR 2.6; 95%CI 1.2–5.4), women who were sales workers (AOR 2.1; 95%CI 1.1–3.9) and women whose ideal number of children was high (AOR; 4.2, 95%CI 1.4–13.0). But the odds of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use was lower among female headed households (AOR 0.2: 95%CI 0.1–0.5) and women who had history of abortion (AOR 0.2: 95%CI 0.1–0.5).

Conclusion

Long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use increased significantly in Ethiopia. Wealth index, women’s occupation, ideal number of children, sex of head of the household and history of abortion were factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use in Ethiopia. Improving economic status of women may help improve long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use in Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

About 50% of women in developing regions of the world want to avoid pregnancy but only three quarters could do so. This causes unintended pregnancies [1]. Births from unintended pregnancies are more likely to suffer from many conditions [2]. In addition, unintended pregnancy increases unnecessary burden on public spending [3].

Long acting and permanent methods (LAPMs) are better options to reduce unintended pregnancies because these methods are more effective, save cost and enable women to control their reproductive lives better [4,5,6]. Use of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods can significantly increase contraceptive prevalence rate in countries with low contraceptive coverage [7]. Women using short acting contraceptives are 21 times more likely to have unintended pregnancy than women using long acting reversible and permanent methods [8]. A projection in SSA countries indicated that more than1.8 million unintended pregnancies would had been averted within 5 yrs period if 20% of women using oral contraceptives and injectable shift to implant [9].

On 2015, long acting and permanent contraceptive methods (Intra uterine device (IUD), implants and sterilization) accounted for 56% of contraceptive use globally. Nineteen percent of married or in-union women relied on female sterilization and 14% used IUD. Yet most contraceptive users in Africa depend on short term methods [7].

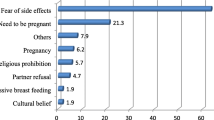

Lack of knowledge, myths, misconceptions and negative attitude about long acting and permanent contraceptive methods are the main barriers for long acting and permanent contraceptive method use in Ethiopia [10]. A study done at Adigrat town, Northwest Ethiopia reported that participants’ knowledge of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods was limited to recognizing the names of the methods. The study added that women had fears and rumors about these methods and prefer methods which do not require procedure [11]. Another study conducted in Dangila town, Ethiopia showed that men had low knowledge about vasectomy [12].

Ethiopia’s health service is structured into three-tier system: primary, secondary and tertiary. The primary level of care includes primary hospitals, health centers (HCs) and health posts (HPs). The primary health care unit (PHCU) comprises five satellite HPs (the lowest-level health facility at village level) and a referral HC. The secondary and tertiary level of care refers to the general hospitals and specialized hospitals respectively [13]. Both long acting and short acting contraceptive methods can be given at all levels of health care [14]. In addition, the government launched an implanon scale up program by task shifting; enabling health extension workers to insert implanon [15]. Family planning is also one of the packages of the health extension program, one of the flagship program in the Ethiopian health system [16].

The Ethiopia government planned to increase contraceptive prevalence rate to 55% in 2020. The government planned to increase implant and IUD to 33 and 15% respectively in the method mix [17]. All contraceptives including long acing and permanent contraceptive methods are provided free in Ethiopia [18]. Many governmental and nongovernmental organizations are providing long acting methods by outreach programs [14, 19]. Regardless of all these efforts, long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use is low. There is huge gap between total demand and demand satisfied. The current contraceptive method mix is dominated with short acting methods [7, 20]. Therefore, this study was designed to examine trends of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use and identify factors associated with its use in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data

To identify factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive method use, the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS) data was used. The EDHS data was collected by the Central statistical Agency (CSA) at the request of the Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH). It was cross-sectional survey collected from January 18, 2016 to June 27, 2016.

The EDHS followed two stage stratified random sampling technique. Enumeration areas were selected in the first stage while households were selected in the second stage. The EDHS collected information about contraceptive use from all non-pregnant, fecund reproductive age women using structured and pretested questionnaire. From 15,683 reproductive age women interviewed for the 2016 EDHS, 9824 (62.6%) were married or in union at the time of survey. One thousand ninety women were excluded from the analysis because they reported being pregnant at the time of survey. Finally, 8734 married reproductive age women were included to identify factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use. The data collectors were trained and had experience in data collection either in previous EDHS or other similar surveys. In addition, team supervisors, field editors, interviewers and secondary editors were recruited and trained by CSA. Data was collected and transferred to the CSA electronically via a secure Internet file streaming system (IFSS) and were stored on a password-protected computer. Then secondary editor resolves computer identified inconsistencies, code open ended questions and perform other activities. All four EDHS (EDHS 2000, 2005, 2011 and 2016) data were used to examine trends of long acting and permanent contraceptive method use.

Measurement

Outcome variable

The outcome variable for this study was contraceptive use. For this analysis, contraceptive use was grouped in to three categories; not using any method, using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods (IUD, female sterilization and implant) and using other methods (short acting and traditional).

Independent variables

The independent variables of the study were categorized in to three groups; socio-demographic, fertility and decision making related, and exposure to family planning programs. Some variables were recoded to have meaningful and small categories.

The main socio-demographic variables include;

-

Age, region, place of residence, educational status, religion, occupation, working status and ethnicity of the woman, household wealth index, sex of head of the household, age, educational status and occupation of partner

Fertility and decision making related variables were;

-

Fertility preference, desire for more children, ideal number of children, husband’s desire for more children, number of children ever born, age at first cohabitation, history of abortion

-

Decision on how to spend earning, on health care, on large household purchase, to visit family and on first marriage

Family planning program exposure variables were

-

Knowledge of the ovulatory period, knowledge of time of fertility, frequency of reading newspaper, frequency of listening radio, heard family planning messages on radio, heard family planning messages on TV, read family planning messages on newspaper, heard family planning messages by mobile phone, visited by health worker, health worker talked about family planning, visited health facility, told about family planning in the health facility.

Analytical methods

After getting permission, the data was downloaded from the DHS program official data base. Analysis was done using Stata 15.1. Open EPI software was used to examine whether there was significant linear trend in long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use in Ethiopia over time. Descriptive analysis was used to describe socio-economic and other variables of the study participants. Tables and graphs were used to present results. The data were weighted to consider the disproportionate sampling and non-response. In addition, the effect of sample design was handled when computing confidence intervals and standard errors. Before running the final model, multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factor. Variables highly correlated with other independent variables were excluded from the final multinomial logistic regression model. Permission to use data was obtained from the DHS programs.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of women

Majority of women were aged 20–34 years. Similarly, most of the participants (83.8%) were rural residents. About two third of mothers did not attend formal education. About 69 % of mothers were not working at the time of survey (Table 1).

Fertility and decision making

The mean ages at first cohabitation and first sex were 17.2 (±4.0) and 16.8 (±3.3) years respectively. The mean number of children ever born was 3.8 (±2.8). The survey indicated that women in Ethiopia had limited knowledge about fertile period. Among all married reproductive age women, only 22.9% correctly know the ovulatory period and only 56.8% knew a woman can get pregnant after birth and before period. A little more than half of the mothers desired to have other children. Majority of women cohabited at age less than 20 years. About two third (60.7%) women reported that their marriage was arranged by parents. About 66 % of women reported that their health care was decided jointly (by partner and themselves) (Table 2).

Exposure to family planning programs

Majority of women did not read newspaper at all (91.7%) did not listen radio at all (69.7%) and did not watch TV at all (76.7%). About 79% women did not own mobile phone. Almost all (97.6%) women never used internet. Only 22.2, 14.1 and 3.3% women reported that they had heard family planning messages on radio, watched on TV and read on newspaper/magazine respectively on the last few months. Only 2.1% women reported that they had received family planning related text message on mobile on the last few months. Many women (70.3%) reported that they were not visited by health worker in the last 12 months (Table 3).

Contraceptive use

About 59 % (95%CI: 55.9–63.0%) women reported that they had ever used or tried something to delay or avoid pregnancy. About one-fourth of mothers (95%CI 26.4–30.9%) reported that they were using short acting or traditional contraceptives methods while 11.6% (95%CI 10.2–13.1%) were using long acting or permanent contraceptive methods. Specifically, 8.8% (95%CI: 7.7–10.1%) and 2.3% (95%CI: 1.7–3.0%) women were using implants and IUD respectively.

Trends in LAPM contraceptive method use

Long acting and permanent contraceptive method use increased significantly (Extended MH chi square for linear trend = 1421.15, p < 0.01) from 0.5% in 2000 to 11.6% in 2016. Implant use showed the highest change from 0.04% in 2000 to 8.8% in 2016 (Extended MH chi square for linear trend = 1231.41, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1). When analyzing the percent change in long acting and permanent contraceptive method use, the highest percentage of change was observed between 2005 and 2011. Both female sterilization and implant use showed the highest percentage increase at this period. But for IUD use, the highest increase was observed from 2011 to 2016 (Fig. 2).

Factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive method use

Multinomial logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive method use. The analysis indicated that wealth index, occupation, sex of head of the household, history of abortion and ideal number of children were significantly associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use (Table 4).

The odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to those not using any method for women in the richer wealth index was 2.6 (AOR 2.6; 95%CI 1.2–5.4) times higher compared to women in the poorest wealth quintile. Similarly, the odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to not using for women who were sales worker was 2.1 (AOR 2.1; 95%CI 1.1–3.9) times higher compared to women who were not working at the time of survey.

The odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to not using for women living in female headed households was 80% lower (AOR 0.2; 95%CI 0.1–0.5) compared to women living in male headed household. The odds of using long acting and permanent of contraceptive methods compared to not using for women who had history of abortion was 80% lower (AOR 0.5; 95%CI 0.1–0.5) compared to women who had no history of abortion. Similarly, The odds of using long acting and permanent method of contraceptive compared to not using for women whose ideal number of children is 1–5 was 4.2 (AOR; 4.2, 95%CI 1.4–13.0) times higher compared to women who desired no more children.

Discussion

Long acting and permanent contraceptive method use

This analysis identified that only 11.6% Ethiopian mothers were using long acting or permanent contraceptive methods. About 9 and 2% of mothers were using implants and IUD respectively. The proportion of women using female sterilization (0.4%) was almost negligible. Vasectomy was nil. The proportion of women using long acting and permanent contraceptives methods was very low compared to the national family planning target of 2020 and the existing high demand for long acting and permanent contraceptive methods. The current practice was also low compared to the national health sector transformation plan and the family planning coasted implementation targets (to increase contraceptive prevalence rate to 55% at the end of 2020 by increasing the share of implant, IUD, female sterilization and vasectomy to 33, 15, 1.5 and 0.5% respectively in the method mix) [20]. In addition, the method mix was dominated by short acting contraceptive methods. Therefore, the government shall intensify task shifting activities launched on 2009. Awareness creation activities to avoid the prevailing myths and misconceptions are crucial.

The proportion of women using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods in this study (11.6%) was much lower than the level of use at global level (which accounted for 56%). In 2015, 19% of married or in-union women relied on female sterilization and 14% used the IUD [7]. The proportion of women using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods in Ethiopia was lower than a study conducted in Kampala, Uganda [21]. But it was similar with a study conducted in Rwanda (10.4%) [22].

The level of long acting and permanent contraceptive method use in this study was lower than meta-analysis done in Ethiopia [23]. The reason for this is that most of the studies included in the meta-analysis were facility based and based on urban settings both of which increase the proportion of women using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods [24,25,26,27,28,29].

Trends of long acting and permanent contraceptive method use

Long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use increased significantly (Extended MH Chi square for linear trend = 1421.15, p < 0.01) in the 16 years period although the level of use was still low compared to the national targets and the existing demand. This finding was similar with a study conducted in Lusaka Zambia which showed that long acting and reversible method use increased from less than 1 to 9% from 2004 to 2011 [30].

Implant use showed the highest change from 0.04% use in 2000 to 8.8% in 2016. This may be due to the task shift designed by the ministry of health. Health extension workers were trained to insert implants [31]. This made the implant accessible to the rural women. The highest percentage change in long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use was observed between 2005 and 2011. The percent change in long acting and permanent contraceptive use was lower from 2011 to 2016. The reason for this may be the presence of high demand for long acting and permanent contraceptive methods from 2005 to 2011. In addition, the government exerted significant effort to address that need at that time. Since that huge gap was addressed from 20,005 to 2011, the percent change from 2011 to 2016 seems lower. But this does not mean long acting and permanent contraceptive method use was lower. Both female sterilization and implant showed the highest percentage increase at this period. But for IUD use, the highest increase was observed from 2011 to 2016. Further qualitative study is needed to explore the reason and learn to increase long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use in Ethiopia.

Factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive method use

The odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to non-use for women in the richer wealth index was higher compared to women in the poorest wealth quintile. This finding was similar with a multi country study conducted in developing countries based on DHS data and the 2011 EDHS data [32, 33]. This may be due to financial barriers to access long acting and permanent methods of contraceptives in Ethiopia. Except implants which are available in health posts, other long acting and permanent contraceptive methods are not easily accessible in Ethiopia. The users have to travel to access these methods of contraceptives. In addition, there is belief or misconception that long acting and permanent contraceptive methods are not convenient for working women [11, 34]. And the poorest are more likely to engage in activities which are more labor intensive. Because of this, the poor may refrain from using these methods.

The odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to non-use for women who were sales worker was higher compared to women who were not working. Many studies in Ethiopia identified that occupation is associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use. A study in Harar city indicated that daily laborers were less likely to use long acting reversible contraceptive methods compared to house wives [35]. A study conducted in Jigjiga showed that employee women were more likely to use long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to house wives [36]. Similar study in Areka town, Southern Ethiopia, indicated that government employees were more likely to use long acting and reversible methods [37]. The possible reason for this is that sales workers are better educated than others which improves their information processing skill. From the data, about 33% of nonworking women attended no education but only 6.2% of sales women did so. Sales workers had also better access to mass media which exposes them to family planning messages. There are evidences in Ethiopia that indicate educated women are more likely to use long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to women who did not attend formal education [35, 38, 39].

The odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to non-use for women living in female headed households was lower compared to women living in male headed household. This finding was similar with a study conducted in Lesotho [40]. The possible reason for this may be that female headed households do have less frequent sexual intercourse compared to male headed households. The husband may be away from home for different reasons. As a result the woman may not use contraceptives or may use short acting methods.

The odds of using long acting and permanent contraceptive methods compared to non-use for women who had history of abortion was lower compared to women who had no history of abortion. This finding contradicts a study in Luanda, Angola, which indicated that history of abortion was associated with contraceptive use [41]. The reason for this may be that women with abortion may have desire for other children. These women may not use contraceptives or will use short acting methods. Women who had abortion may also associate the abortion with long acting methods use and refrain from using.

The odds of using long acting and permanent methods of contraceptive compared to not using for women whose ideal number of children is 1–5 was higher compared to women who did not want any child. This finding contradict with a community based study conducted in Amhara region, Ethiopia which indicated that women with higher ideal number of children are less likely to use long acting methods [42]. The reason for this may be that women who desired no children are older women who are using short acting methods or not using any method thinking that they are approaching menopause.

The strength of this study is that it is based on nationally representative, large data. On the other hand, some factors are not included in the analysis as it is secondary data.

Conclusion

Although increasing significantly, the current level of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use was still low in Ethiopia compared to the national targets. The odds of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use were high among women in the richer wealth index, among women who were sales workers and among women who desired more children. On the other hand, the odds of use were lower among women with female headed households and women with history of abortion.

Further research is needed to identify the different levels of change in long acting and contraceptive use in Ethiopia. Emphasis should be given to women in the lower wealth quintile and women who had history of abortion to improve long acting and permanent contraceptive method use.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets analyzed during this study are available in the DHS programs repository available at https://dhsprogram.com/

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CSA:

-

Central Statistical Agency

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- FMoH:

-

Federal Ministry of Health

- IUD:

-

Intrauterine Device

- LAPM:

-

Long Acting and Permanent contraceptive method

- MH:

-

Mantel-Haenszel

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TV:

-

Television

References

Guttmacher Intitute. Adding it up: investing in contraception and maternal and newborn health, 2017. 2017.

Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39(1):18–38.

Sonfield A, Kost K, Gold RB, Finer LB. The public costs of births resulting from unintended pregnancies: national and state-level estimates. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(2):94–102.

Blumenthal P, Voedisch A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy: increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;17(1):121–37.

Joshi R, Khadilkar S, Patel M. Global trends in use of long-acting reversible and permanent methods of contraception: seeking a balance. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:S60–S3.

Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998–2007.

United Nations Department of economic and social affairs population division. Trends in contraceptive use worldwide 2015. 2015.

Lotke PS. Increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception to decrease unplanned pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2015;42(4):557–67.

Hubacher D, Mavranezouli I, McGinn E. Unintended pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: magnitude of the problem and potential role of contraceptive implants to alleviate it. Contraception. 2008;78(1):73–8.

Mengistu Meskele WM. Factors affecting women’s intention to use long acting and permanent contraceptive methods in Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC women's health. 2014;14:109.

Gebremariam A, Addissie A. Knowledge and perception on long acting and permanent contraceptive methods in Adigrat town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Int J Family Med. 2014;2014.

Abrham Jemberie Temach GAFaAAA. Educational status as determinant of men’s knowledge about vasectomy in Dangila town administration, Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2017;14(54).

Organization WH. Primary health care systems (PRIMASYS): case study from Ethiopia, abridged version. Geneva2017.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. National Guideline for family planning Services in Ethiopia. 2011.

Yewondwossen Tilahun CL, Belayihun B, Hagos KL, Asnake M. Improving contraceptive access, use, and method mix by task sharing Implanon insertion to frontline health workers: the experience of the integrated family health program in Ethiopia. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2017;5(4).

MoH E. In: Heae c, editor. Health extension program in Ethiopia; 2007.

Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia ministry of health. Health sector transformation plan. 2015.

Ministry of Health Ethiopia, PMNCH, WHO, World Bank, AHPSR, Participants in the Ethiopia multistakeholder policy review (2015). Success Factors for Women’s and Children’s Health: Ethiopia. 2015.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Minstry of Health. Family Planning 2017 [updated August 27, 2017]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.et/ejcc/en/mch.

Minstry of Health Ethiopia. Costed implementation plan for family planning in Ethiopia, 2015/16–2020. 2016.

Anguzu R, Tweheyo R, Sekandi JN, Zalwango V, Muhumuza C, Tusiime S, et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards use of long acting reversible contraceptives among women of reproductive age in Lubaga division, Kampala district, Uganda. BMC research notes. 2014;7(1):153.

Bikorimana E. Barriers to the use of long acting contraceptive methods among married women of reproductive age in Kicukiro District. Rwanda International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 2015:513.

Mesfin YM, Kibret KT. Practice and intention to use long acting and permanent contraceptive methods among married women in Ethiopia: systematic meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):78.

Melka AS, Tekelab T, Wirtu D. Determinants of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods utilization among married women of reproductive age groups in western Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2015;22(1).

Takele A, Degu G, Yitayal M. Demand for long acting and permanent methods of contraceptives and factors for non-use among married women of Goba town, bale zone, south East Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2012;9(1):26.

Bulto GA, Zewdie TA, Beyen TK. Demand for long acting and permanent contraceptive methods and associated factors among married women of reproductive age group in Debre Markos town, north West Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):46.

Mekonnen G, Enquselassie F, Tesfaye G, Semahegn A. Prevalence and factors affecting use of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods in Jinka town, southern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2014;18(1).

Haile A, Fantahun M. Demand for long acting and permanent contraceptive methods and associated factors among family planning service users, Batu town, Central Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2012;50(1):31–42.

Alemayehu M, Belachew T, Tilahun T. Factors associated with utilization of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods among married women of reproductive age in Mekelle town, Tigray region, North Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy childbirth. 2012;12(1):6.

Hancock NL, Chibwesha CJ, Stoner MC, Vwalika B, Rathod SD, Kasaro MP, et al. Temporal trends and predictors of modern contraceptive use in Lusaka, Zambia, 2004–2011. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015.

International P. Scale-up of task-shifting for community-based provision of Implanon. 2009–2011.

Ugaz JI, Chatterji M, Gribble JN, Banke K. Is household wealth associated with use of long-acting reversible and permanent methods of contraception? A multi-country analysis. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2016;4(1):43–54.

Yigzaw M, Zakus D, Tadesse Y, Desalegn M, Fantahun M. Paving the way for universal family planning coverage in Ethiopia: an analysis of wealth related inequality. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):77.

Tilahun Y, Mehta S, Zerihun H, Lew C, Brooks MI, Nigatu T, et al. Expanding access to the intrauterine device in public health facilities in Ethiopia: a mixed-methods study. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2016;4(1):16–28.

Shiferaw K, Musa A. Assessment of utilization of long acting reversible contraceptive and associated factors among women of reproductive age in Harar City. Ethiopia Pan African Medical Journal. 2017;28(1).

Abdisa B, Mideksa L. Factors associated with utilization of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods among women of reproductive age Group in Jigjiga Town. Anat Physiol. 2017;7(254).

Kabalo MY. Utilization of reversible long acting family planning methods among married 15-49 years women in Areka town, southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Scientific Reports. 2016;2(1):1–6.

Tekelab T, Sufa A, Wirtu D. Factors affecting intention to use long acting and permanent contraceptive methods among married women eproductive age groups in Western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Fam Med Med Sci Res. 2015;4(158):2.

Bayisa A, Lema M. Factors associated with utilization of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods among women of reproductive age Group in Jigjiga Town. Anat Physiol. 2017;7(256).

Makatjane T. Contraceptive prevalence in Lesotho: does the sex of the household head matter? Afr Popul Stud. 1997;12(2):1–11.

Morris N, Prata N. Abortion history and its association with current use of modern contraceptive methods in Luanda, Angola. Open Access J Contracept. 2018;9:45.

Nejimu Biza MA, Surender Reddy P. Long acting reversible contraceptive use and associated factors among contraceptive users in Amhara Region, Ethopia, a community based cross sectional study. Med Res Chron. 2017;4(5).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Pan African University, Institute of Life and Earth Science (including health and agriculture) and University College Hospital, Ibadan University for all assistance to prepare this manuscript. The authors are grateful to the DHS programs for allowing the data to use.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from research ethics committee, the University College Hospital, University of Ibadan. Written informed consent was obtained from all women who participated on all Ethiopian demographic and health surveys.

Funding

No funding for this study since it is secondary data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mr. Gedefaw Abeje Fekadu initiated the study, analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. Professor Akinyinka O. Omigbodun, Dr. Olumuyiwa A. Roberts and Professor Alemayehu Worku Yalew assisted the development of the research idea, the analysis, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

Mr. Gedefaw Abeje Fekadu is PhD candidate in Reproductive health sciences Pan African University, Institute of Life and Earth Science (including health and agriculture), University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria and assistant professor of reproductive health in Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Professor Akinyinka O. Omigbodun is senior gynecologist and obstetrician in University College Hospital, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria. Dr. Olumuyiwa A. Roberts is also senior gynecologist and obstetrician in the same institute. Professor Alemayehu Worku Yalew is professor of public health in Addis Ababa University, School of Public Health.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fekadu, G.A., Omigbodun, A.O., Roberts, O.A. et al. Factors associated with long acting and permanent contraceptive methods use in Ethiopia. Contracept Reprod Med 4, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-019-0091-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-019-0091-3