Abstract

Background

In clinical practice, plant extracts are an option to treat mild-to-moderate lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostate hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH). However, only a few herbal extracts have been investigated in long-term placebo-controlled studies. The safety and efficacy of a well-tolerated proprietary pumpkin seed soft extract (PSE) were investigated in two randomized placebo-controlled 12-month studies (Bach and GRANU study). Both trials studied LUTS/BPH patients with an International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) ≥13 points at baseline. The Bach study demonstrated positive effects of PSE compared to placebo, but no difference between treatments was observed in the GRANU study. We aimed to assess the efficacy of PSE in a meta-analysis using the patient-level data of these two studies.

Methods

Pooled analysis was performed in the intention-to-treat set using last-observation-carried-forward (ITT-LOCF). An IPSS improvement of ≥5 points after 12 months of therapy was the predefined response criterion. Logistic regression and ANCOVA models included the covariables treatment group, study, center size, and baseline IPSS. Each analysis was repeated for the per-protocol (PP) set.

Results

The ITT/PP analysis sets consisted of 687/485 and 702/488 patients in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively. At the 12-month follow-up, the response rates in the PSE group were 3% (ITT) and 5% (PP) higher than those in the placebo group. The odds ratio of response obtained by logistic regression analysis for comparing PSE versus placebo was 1.2 (95% CI 0.9, 1.5), favoring PSE (ITT- LOCF). For the IPSS change from baseline to 12 months, the ANCOVA estimated difference between the treatment groups was 0.7 points (95% CI 0.1, 1.2) in favor of PSE. The variables study, baseline IPSS, and center size had a relevant influence on treatment response.

Conclusion

Although the Bach and the GRANU study showed contradictory results, the analysis in a pooled form still pointed towards an advantage of PSE; namely, more patients in the PSE group showed an IPSS improvement of at least 5 points after 12 months. Therefore, the results of this meta-analysis suggest that patients with moderate LUTS/BPH may benefit from PSE treatment in terms of symptomatic relief.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) are common in aging men. For decades, the symptoms of this condition have been treated with phytotherapy. Various preparations are available, mainly consisting of extracts from saw palmetto fruit, pumpkin seed, pygeum africanum bark, nettle root, or willow herb [1, 2]. Meanwhile, selective alpha1-receptor blockers (ARBs) and 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) have increasingly served as first-line medical treatments since they came on the market in the 1990s. However, synthetic drugs have potential side effects that might negatively influence quality of life, such that many patients prefer herbal products due to their excellent safety profile. Thus, plant extracts have been continuously used in clinical practice [3,4,5].

In recent years, symptom bother and quality of life have become key criteria for therapy decisions [6, 7]. Considering patient preferences has led to debates about the role of phytotherapy particularly in patients with a low risk of disease progression [4, 8, 9].

Since 2014, the German S2e guideline suggests the option of treating LUTS/BPH with herbal preparations of proven superiority to placebo in patients who have mild-to-moderate complaints and refuse chemical compounds [6].

Notably, relevant placebo responses have regularly been observed in randomized controlled trials in patients with LUTS/BPH [10]. The placebo effect is rapid and may account for 40-60% of the overall symptom relief but tends to diminish over time [10,11,12]. Consequently, the International Consultation on BPH emphasized the importance of placebo control and follow-up periods of at least 12 months for clinical research in the early 1990s [13].

Nonetheless, most studies with herbal preparations have shortcomings, such as brief follow-up periods up to only 6 months, lack of placebo control, and small samples with less than 100 participants per treatment group [6, 14, 15]. To date, no more than five randomized placebo-controlled long-term studies in patients with LUTS/BPH have been reported [6]. Notably, two of these 12-month studies investigated pumpkin seed soft extract (PSE)Footnote 1 [16, 17].

The first study, published by Bach [16], showed significant IPSS improvement with PSE versus placebo, and its 12-month follow-up period was recognized as an exception in clinical research on phytotherapy for LUTS/BPH [6].

The second study (GRANU study) was a three-arm trial testing the efficacy and safety of pumpkin seed (open study arm) and PSE capsules against matching placebo. This study showed no difference between PSE and placebo [17].

Nonetheless, these two placebo-controlled studies have established the long-term safety of the extract; less than 1% of more than 700 patients treated with PSE reported adverse events with a possible causal relationship to treatment [16, 17]. The reactions were nonserious, and most of them were gastrointestinal complaints. The types and frequency of all recorded adverse events in the PSE group were similar to those in the placebo group. Serum PSA levels and other laboratory safety parameters showed no relevant changes from baseline after 12 months of treatment [16, 17]. An observational study confirmed the excellent safety profile of PSE in a large population of 2245 men with LUTS/BPH. After 3 months of treatment, the patients reported symptomatic relief and improved quality of life. Simultaneously, only mild gastrointestinal complaints were reported in no more than 4% of the patients [18].

In terms of efficacy, we performed a meta-analysis to estimate the benefits of PSE compared to placebo using the data from the original reports of the Bach and GRANU study. Since we used the individual patient listings, the meta-analysis also involved the reanalysis of the initial studies enabling us to provide supplementary information about the individual studies. In addition, we aimed to explore the possible influences of covariates on treatment response using statistical models.

Materials and methods

Description of the studies included in the meta-analysis

Design, conduct, and target populations

The Bach and the GRANU study followed the clinical research criteria established by the WHO-sponsored International Consultation on BPH [13]; both studies were randomized and placebo-controlled, had a treatment period of 12 months, and used the IPSS as the primary efficacy variable; eligible patients had to have an IPSS of at least 13 points (Table 1, Supplementary Table A).

Intervention

The active treatment in both studies consisted of pumpkin seed soft extract (PSE) given in capsules (500 mg BID). PSE is a proprietary extract manufactured from the seeds of Uromedic® pumpkin, a company-owned registered cultivar of Cucurbita pepo L. convar. Citrullinina GREB. var. styriaca GREB (extraction solvent ethanol 92% [w/w]; drug-extract ratio: 15-25:1). The extract has a high content of Δ7-phytosterols (Δ7,25-stigmasterol, spinasterol, Δ7-avenasterol) that are specific putative active constituents of pumpkin seeds [19]. One capsule with 500 mg PSE contains approximately 15 mg of Δ7-phytosterols [20]. Placebo capsules contained the active capsules’ excipients and macrogol 400 as an inert substitute for the extract.

PSE and placebo capsules were indistinguishable by taste, smell, size, shape, and color. Independent statisticians who were not involved in the study analyses generated permuted, balanced block randomization lists stratified by study site. According to the randomization schedule, the study medications were packed in identical, neutral boxes, each with a patient number. After the 1-month run-in period, eligible patients were randomly assigned to 12-month treatment with either PSE (500 mg BID) or placebo (Table 1).

Only complete random blocks were allocated to each study center. The block size was not stated in the study protocols. The investigator assigned patients to a treatment using the study medication with the next consecutive random number. In the partially blinded GRANU study, opaque, sealed, serially numbered envelopes were used as previously described [17].

Until the studies were unblinded, staff involved in the study conduct and analyses were unaware of the treatment allocation. Randomization lists were only opened after completing data cleaning and patient assignments to the analysis sets.

Efficacy variables

The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was the primary efficacy variable. Patients were classified as responders if they had a decrease in IPSS of at least 5 points from baseline after 12 months of treatment. In addition, the mean changes from baseline in IPSS and related quality of life (IPSS QoL) were analyzed for all visits.

The IPSS is a self-administered 7-item patient questionnaire covering the symptoms incomplete emptying, frequency, intermittency, urgency, weak urinary stream, straining, and nocturia. An additional question assesses the IPSS-related quality of life (IPSS QoL). On a 6-point scale, patients rate the frequency of each symptom from 0 (‘never’) to 5 (‘almost always’). Total IPSS ranges between 0 and 35 points. Although alone not suitable to diagnose the presence of BPH, the IPSS is a clinically reliable and worldwide accepted tool to assess and follow-up the severity of LUTS/BPH [6, 13]. According to the IPSS total score, symptom severity is categorized as mild (IPSS< 8), moderate (IPSS = 8-19), or severe (IPSS = 20-35) [7, 21]. An IPSS reduction by a minimum of 3 points is considered a perceivable change for the patient [21,22,23,24]. Thus, a 5-point IPSS decrease represents a clinically relevant therapeutic response [24].

The answers to the single IPSS QoL question range between 0 (delighted) and 6 (terrible) [13, 21].

Secondary parameters included maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), postvoid residual volume (PVR), and prostate volume (PV) measured at baseline and after 12 months of treatment.

Statistical methods

The methods of data handling and analysis were prespecified in a statistical analysis plan. All statistical evaluations were performed using the software package SAS release 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Data extraction and handling

The individual patient data owned by the present manufacturer of PSE were used to perform the meta-analysis. For the Bach study, an electronic database was not available. Therefore, data from paper-based lists were captured in electronic form. When entering the data, the IPSS QoL score values ranging from 1 to 7 were reduced by one unit to adjust them to the more common range from 0 to 6 used in the GRANU study.

For the GRANU study, PSE and placebo patient data were extracted from the existing electronic database.

Analysis sets

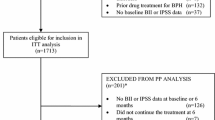

The intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis set consisted of all randomized patients who took at least one study medication and had baseline and at least one postbaseline IPSS assessment. For the per-protocol (PP) analysis set, the original assignments of each study were retained (Fig. 1).

The meta-analysis was performed for the ITT set using last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF). Each analysis was repeated for the PP set with observed data.

Efficacy analysis

The primary efficacy time point was the last follow-up visit after 12 months. According to the original studies’ definition, the response criterion was a 5-point IPSS reduction after 12 months of treatment. Response rate differences between the PSE and placebo groups were statistically tested by Fisher’s exact test. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Wilson’s score method.

Statistical significance refers to a two-sided type I error of 5%. No adjustments for multiplicity were made.

To compare the changes from baseline in IPSS and secondary parameters between treatment groups, P values were calculated using the t test, assuming equal variances. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using t distribution.

Furthermore, response rates and mean changes in IPSS from baseline to 12 months were investigated using logistic regression and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models with treatment, study, baseline IPSS, and center size as independent variables. Study sites were classified according to their number of recruited patients into low (1-3 patients), medium (4-10 patients), and high (> 10 patients) center sizes. P values were calculated using the Wald test.

Ethical aspects

Approvals from responsible ethics committees and authorities were obtained for the original studies. All participants provided written informed consent before any screening examination. Thus, further institutional approval was not required for the present analysis.

Results

Patient disposition

The pooled analysis set comprised 1432 patients (PSE, 714; placebo, 718). Forty-three patients (PSE, 27; placebo, 16) were excluded from analysis, mostly due to missing postbaseline IPSS assessment. The ITT and PP sets consisted of 1389 and 973 patients, respectively (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, treatment groups were homogeneous for demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 2 [ITT], Supplementary Table B [PP]). On average, the ITT patients were approximately 64.4 years old and had IPSS and IPSS QoL scores of 16.6 and 3.4 points, respectively The means of Qmax, PVR, and PV were 10.1 mL/s, 38.6 mL, and 30.2 mL, respectively (Table 2).

Approximately 11%, 29%, and 60% of the ITT patients (N = 1389) were treated in low-, medium-, and high-recruiting centers, respectively (Table 3).

Primary efficacy

The IPSS continuously declined in both treatment groups (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table C). After the 12-month treatment period, the response rates in the PSE group exceeded those in the placebo group by 3% (ITT) and 5% (PP) (Table 4). Figure 3 shows the forest plot for the primary analysis set (ITT set using LOCF). The mean IPSS changes from baseline after 12 months were − 5.3 points in the PSE group and − 4.8 points in the placebo group (ITT using LOCF, Supplementary Table C). The mean change difference between the treatment groups was 0.6 points in favor of PSE (Fig. 4).

Forest plot showing the difference (with 95% CI) between treatments (PSE minus placebo) in IPSS response rates after 12 months of treatment; ITT set using LOCF. PSE pumpkin seed soft extract. The response rate is the number of responders divided by the total number of patients treated in the respective group

Logistic regression results

The logistic regression analysis of response rates in the ITT set resulted in an odds ratio (OR) of 1.17 for comparing PSE and placebo treatment and of 1.28 for comparing the Bach and GRANU studies (Table 5). The baseline IPSS had a relevant influence on treatment response (OR, 1.17 [per one-point increase in the IPSS baseline score]). Additionally, the variable center size affected a patient’s chance of achieving the response criterion. The effect was conspicuous (OR, 0.6) when comparing low- and high-recruiting centers (Table 5).

ANCOVA results

After 12 months, the mean IPSS change from baseline estimated by ANCOVA showed a difference between treatments of 0.7 points (95% CI 0.1, 1.2) in favor of PSE. Again, the influence of the variables study (Bach vs. GRANU), baseline IPSS, and center size (low- vs. high-recruiting centers) on the magnitude of IPSS change was present (Table 6).

Secondary variables

In the ITT set, the mean IPSS QoL scores were reduced by 0.9 and 0.8 points during the first 3 months of treatment in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively. After 12 months, the mean IPSS QoL scores were 1.2 points (PSE) and 1.1 points (placebo) lower than the scores at baseline (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table D).

Table 7 shows the changes in Qmax, PVR, and PV from baseline to the 12-month follow-up.

Specific characteristics of the individual studies

Baseline

In both studies, all baseline characteristics were well balanced between PSE and placebo groups in the ITT (Table 2) and PP sets (Supplementary Table B). However, when comparing the data between the two studies, conspicuous differences were found for some demographic and clinical parameters. On average, the patients in the GRANU study were approximately 3 years older than the Bach study patients. The mean baseline IPSS was 16.0 points in the GRANU study compared to 17.6 points in the Bach study (ITT sets, Table 2).

The upper PV limit of 40 mL for inclusion in the GRANU study resulted in a lower mean PV of 29 mL compared to 35 mL in the Bach study. The mean Qmax was 9.6 mL in the GRANU study and 11.0 mL in the Bach study (Table 2).

IPSS outcome

In the Bach study, the response rate of the PSE group (65%) was significantly higher than that of the placebo group, with a difference of 11% (95% CI 1%, 20%) (Table 4). For the mean IPSS change from baseline, the difference between PSE and placebo after 12 months was − 1.1 points (95% CI -2.0, − 0.1) in favor of PSE (Supplementary Table C). Conversely, in the GRANU study, response rates and changes from baseline after 12 months of treatment did not differ between PSE and placebo patients (ITT set, Table 4). Details of these results were comprehensively published in 2015 [17],

IPSS QoL

In each study, the IPSS QoL index decreased in both treatment groups, with major improvement occurring during the first 3months. After 12 months, the mean reduction in the IPSS QoL score from baseline in the Bach study was 1.3 and 1.1 points in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively, and the mean decreases in the GRANU study were 1.2 points (PSE group) and 1.0 points (placebo group) (Supplementary Table D).

Urological measurements

Qmax, PVR, and PV changes from baseline to 12 months of treatment are shown in Table 7. In either study, the Qmax improved in both treatment arms. In the Bach study, the increase was 3.9 mL/s and 3.3 mL/s in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively, and in the GRANU study, the mean difference from baseline was the same for both treatments (+ 3.6 mL/s).

The median reduction in PVR was 10 mL in both treatment groups of the Bach study, while in the GRANU study, which excluded patients having a PVR over 100 mL, the median change from baseline after 12 months was zero (0.0 mL) in either group (Table 7).

The individual changes in PV from baseline to the 12-month follow-up varied between a 123 mL increase and a 70 mL decrease in the Bach study. In addition to potential measurement errors, transient prostatic congestions most likely concomitantly present at baseline or after 12 months accounted for large volume changes in individual patients. The mean (SD) change from baseline was − 1.7 (15.1) mL and - 4.0 (17.7) mL in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively. Conversely, in the GRANU study, PV values were increased at study end compared to baseline. The mean/median increases after 12 months were 2.4 / 1.0 mL and 2.6 / 2.0 mL in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively (Table 7).

Discussion

In everyday clinical practice, phytotherapy is part of standard therapy for men with uncomplicated but bothersome LUTS suggestive of BPH. The favorable safety profile of herbal extracts is well recognized. However, the efficacy evidence is mainly based on highly heterogeneous studies, and meta-analyses should be interpreted with caution [4, 6, 7].

The present meta-analysis on the efficacy of soft extract from Uromedic® pumpkin seed (PSE) pooled two studies with basically homogenous designs. Both the Bach and GRANU studies were placebo-controlled and had the same follow-up period of 12 months.

Consistent with the primary studies, an IPSS reduction of ≥5 points from baseline was the threshold of response in the pooled analysis. Thus, responders had an improvement that exceeded the minimum 3-point improvement a patient needs to perceive a clinical benefit [21,22,23].

The analyzed population consisted of 1389 men aged 64 years on average. At baseline, the patients had mean IPSS and IPSS QoL scores of 16.6 and 3.4 points, respectively. This level of moderate LUTS and related impact on quality of life is typical for patients who seek medical advice and treatment for symptomatic relief [2].

In these patients, the meta-analysis results suggest beneficial effects of PSE in terms of symptomatic relief. After 12 months, the response rate in the PSE group was 54% (ITT-LOCF) compared to 51% in the placebo group. An advantage of PSE treatment was also observed in the PP set, with response rates of 58% and 53% in the PSE and placebo groups, respectively. Additionally, the mean IPSS change from baseline was greater with PSE (− 5.3 points) than with placebo (− 4.8 points).

The magnitude of symptomatic relief achieved with PSE after 12 months compares favorably with the findings by Debruyne et al. [25] for hexanic saw palmetto extract and tamsulosin. With these treatments, only 49% of the patients reached an IPSS decrease of ≥5 points, and the mean IPSS change from baseline was − 4.4 points. Notably, based on that study, the European herbal monograph has granted well-established use status for hexanic saw palmetto extract [26].

In a recent meta-analysis, Russo et al. [27] found minimal differences in IPSS response between saw palmetto extracts and placebo. However, this analysis was based on studies with immense variability regarding essential features. The small number of patients resulted in significant imbalances in baseline IPSS with up to a 2.9-points difference between the treatment groups in 4 out of the 5 studies.

Another meta-analysis of all available published data for hexanic saw palmetto extract showed a mean IPSS decrease of 5.73 [2, 15]. However, only 6 of the primary studies were randomized controlled trials, of which only one had a 12-month follow-up period, and none was placebo-controlled [15, 25].

In contrast, the two PSE studies pooled for the present meta-analysis were equal regarding essential requirements of clinical research in patients with LUTS/BPH, such as placebo control and 12-month follow-up [13]. As we used patient-level data, our study also repeated the analysis of the individual studies [28]. All re-evaluation results were consistent with the initially reported study data [16, 17].

In both studies, the baseline characteristics were well-balanced between treatment groups. However, we noticed possibly important differences between the studies due to the strict selection criteria in the GRANU study conducted approximately a decade after the Bach study [16]. During this period, ARBs and 5-ARIs had become standard prescription drugs for symptomatic LUTS in Germany [6, 29]. Thus, the ethics committee tightened the inclusion criteria because treating patients with severe LUTS was no longer accepted in placebo-controlled studies. Consequently, the upper IPSS limit for inclusion was 19 points in the GRANU study [17].

To some extent, the lower baseline scores in the GRANU study might have reduced the magnitude of IPSS improvement. Notably, the logistic regression and ANCOVA models showed that symptom severity at baseline substantially influenced the IPSS reduction. These findings correspond to other observations, e.g., Roehrborn et al. reported that patients with baseline IPSS above 19 points reached a 3-point reduction more often than patients having lower scores at study start [23]. Similarly, Debryne et al. [25] reported a better treatment response in patients with severe symptoms compared to patients with moderate symptoms.

Of the patients studied in the present meta-analysis, approximately two-thirds (924 out of 1389) included in our meta-analysis had been treated in the GRANU study. Thus, a study population with less severe symptoms and no difference between PSE and placebo dominated the present results. Nonetheless, in the pooled analysis of both studies, the estimated response rates in the PSE group exceeded those in the placebo group by 3% and 5% in the ITT and PP sets, respectively. Furthermore, according to the logistic regression model, a patient’s likelihood of achieving a 5-point decrease in the IPSS was 17% higher in the PSE group than in the placebo group. Moreover, regarding the mean IPSS changes from baseline to 12 months the difference between the PSE and placebo groups also favored PSE treatment. In both treatment groups, the decrease in IPSS was accompanied by an improvement in the IPSS-QoL index.

Conclusions

Herbal preparations such as pumpkin seed soft extract may be an option for the symptomatic treatment of men with mild-to-moderate LUTS/BPH and low risk of progression. According to our meta-analysis of two 12-month studies, more patients treated with pumpkin seed soft extract achieved the clinically relevant response of an at least 5-point decrease in total IPSS than patients in the placebo group. The extract was well tolerated. No treatment-related changes were observed in laboratory safety parameters, including PSA values after 12 months of treatment [16, 17].

Accordingly, for men seeking symptomatic relief of LUTS, pumpkin seed soft extract may offer a favorable balance between desirable and undesirable outcomes, particularly for those who refuse or do not tolerate synthetic drugs. The possible association between treatment response and baseline IPSS warrants confirmation in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

All data concerned with this research have been mentioned in this manuscript and its supplementary information file.

Notes

Soft extract from the seeds of Uromedic® pumpkin is the active ingredient of medicinal products for the treatment of LUTS/BPH. Brand names are GRANU FINK Prosta forte 500 mg (DE), GRANU FINK Prosta kemény (HU), GRANUFINK Prosta forte (AT, CH, NL, UA), and Urostemol Prosta (UK).

Abbreviations

- 5-ARI:

-

5-alpha-reductase inhibitor

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- ARB:

-

Alpha1 - receptor blocker

- BL:

-

Baseline

- BPH:

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EAU:

-

European Association of Urology

- IPSS:

-

International Prostate Symptom Score

- IPSS QoL:

-

IPSS-related quality of life

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- LOCF:

-

Last-observation-carried-forward

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PP:

-

Per-protocol

- PSE:

-

Pumpkin seed soft extract

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- PV:

-

Prostate volume

- PVR:

-

Postvoid residual volume

- Qmax :

-

Maximum urinary flow rate

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SAS:

-

Statistical Analysis System

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

References

Đorđević I, Milutinović M, Kostić M, Đorđević B, Dimitrijević M, Stošić N, et al. Phytotherapeutic approach to benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment by pumpkin seed (Cucurbita Pepo L., Cucurbitaceae). Acta Med Medianae. 2016;55(3):76–84 http://scindeks-clanci.ceon.rs/data/pdf/0365-4478/2016/0365-44781603076D.pdf.

Gravas S, Cornu JN, Gacci M, Gratzke C, Herrmann TRW, Mamoulakis C, et al. EAU Guidelines on Management of Non-Neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), incl. Benign Prostatic Obstruction. 2021 https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-on-Management-of-Non-Neurogenic-Male-LUTS-2021.pdf.

Fourcade RO, Theret N, Taieb C. Profile and management of patients treated for the first time for lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia in four European countries. BJU Int. 2008;101(9):1111–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.464-410X.2008.07498.x.

Fornara P, Madersbacher S, Vahlensieck W, Bracher F, Romics I, Kil P. Phytotherapy adds to the therapeutic armamentarium for the treatment of mild-to-moderate lower urinary tract symptoms in men. Urol Int. 2020;104(5-6):333–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504611.

Ullah R, Wazir J, Hossain MA, Diallo MT, Khan FU, Ihsan AU, et al. A glimpse into the efficacy of alternative therapies in the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(3):153–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-020-1692-z.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie. DGU, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie. S2e Leitlinie Therapie des Benignen Prostatasyndroms (BPS). Akademie der Deutschen Urologen. AWMF-Reg.Nr.: 043-035. 2014. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/043-035.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2021.

Gravas S, Cornu JN, Gacci M, Gratzke C, Herrmann TRW, Mamoulakis C, et al. EAU Guidelines on Management of Non-Neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), incl. Benign Prostatic Obstruction (BPO). 2019. https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-on-the-Management-of-Non-Neurogenic-Male-LUTS-2019.pdf. Assessed 11 Jan 2021.

Fourcade R-O, Lacoin F, Rouprêt M, Slama A, Le Fur C, Michel E, et al. Outcomes and general health-related quality of life among patients medically treated in general daily practice for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Urol. 2012;30(3):419–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-011-0756-2.

Pinggera GM, Frauscher F. Do we really need herbal medicine in LUTS/BPH treatment in the 21(st) century? Exp Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(12):1573–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2016.1214267.

Eredics K, Madersbacher S, Schauer I. A relevant midterm (12 months) placebo effect on lower urinary tract symptoms and maximum flow rate in male lower urinary tract symptom and benign prostatic hyperplasia-a Meta-analysis. Urology. 2017;106:160–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.05.011.

Sech SM, Montoya JD, Bernier PA, Barnboym E, Brown S, Gregory A, et al. The so-called "placebo effect" in benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment trials represents partially a conditional regression to the mean induced by censoring. Urology. 1998;51(2):242–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00609-2.

van Leeuwen JH, Castro R, Busse M, Bemelmans BL. The placebo effect in the pharmacologic treatment of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2006;50(3):440–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2006.05.014.

Aso Y, Baccon-Gibob L, Calais da Silva F, Cockett ATK, Moriyama N, Okajima E, et al. Clinical Research Criteria. In: Cockett ATK, Chatelain C, Aso Y, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd International Consultation on Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), Paris, 1993. Jersey: Scientific Communication International Ltd; 1993. p. 345–58.

Madersbacher S, Berger I, Ponholzer A, Marszalek M. Plant extracts: sense or nonsense? Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18(1):16–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f0d5c8.

Vela-Navarrete R, Alcaraz A, Rodríguez-Antolín A, Miñana López B, Fernández-Gómez JM, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a hexanic extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon(®) ) for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH): systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BJU Int. 2018;122(6):1049–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14362.

Bach D. Placebokontrollierte Langzeittherapiestudie mit Kürbissamenextrakt bei BPH-bedingten Miktionsbeschwerden. Der Urologe B. 2000;40(5):437–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001310050432.

Vahlensieck W, Theurer C, Pfitzer E, Patz B, Banik N, Engelmann U. Effects of pumpkin seed in men with lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia in the one-year, randomized, Placebo-Controlled GRANU Study. Urol Int. 2015;94(3):286–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000362903.

Damiano R, Cai T, Fornara P, Franzese CA, Leonardi R, Mirone V. The role of Cucurbita pepo in the management of patients affected by lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a narrative review. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;88(2):136–43. https://doi.org/10.4081/aiua.2016.2.136.

EMA/HMPC. Assessment report on Cucurbita pepo L., semen. European Medines Agency/Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products EMA/HMPC/136022/2010. 2012. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-report/final-assessment-report-cucurbita-pepo-l-semen_en.pdf. Assessed 11 Jan 2021.

Müller C, Bracher F. Determination by GC-IT/MS of Phytosterols in herbal medicinal products for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and food products marketed in Europe. Planta Med. 2015;81(7):613–20. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1545906.

Barkin J. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms: evidence and approaches for best case management. Can J Urol. 2011;18(Suppl):14–9 PMID: 21501546.

Braeckman J, Denis L. Management of BPH then 2000 and now 2016 - from BPH to BPO. Asian J Urol. 2017;4(3):138–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2017.02.002.

Roehrborn CG, Casabe A, Glina S, Sorsaburu S, Henneges C, Viktrup L. Treatment satisfaction and clinically meaningful symptom improvement in men with lower urinary tract symptoms and prostatic enlargement secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: secondary results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind study comparing finasteride plus tadalafil with finasteride plus placebo. Int J Urol. 2015;22(6):582–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.12741.

Barry MJ, Girman CJ, O'Leary MP, Walker-Corkery ES, Binkowitz BS, Cockett AT, et al. Using repeated measures of symptom score, uroflowmetry and prostate specific antigen in the clinical management of prostate disease. Benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment outcomes study group. J Urol. 1995;153(1):99–103. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-199501000-00036.

Debruyne F, Koch G, Boyle P, Da Silva FC, Gillenwater JG, Hamdy FC, et al. Comparison of a phytotherapeutic agent (Permixon) with an alpha-blocker (Tamsulosin) in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a 1-year randomized international study. Eur Urol. 2002;41(5):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00066-0.

EMA/HMPC. Assessment report on Serenoa repens (W. Bartram) Small, fructus. EMA/HMPC/137250/2013. 2015.

Russo GI, Scandura C, Di Mauro M, Cacciamani G, Albersen M, Hatzichristodoulou G, et al. Clinical efficacy of Serenoa repens Versus placebo versus alpha-blockers for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic enlargement: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7(2):420–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2020.01.002.

Ebrahim S, Sohani ZN, Montoya L, Agarwal A, Thorlund K, Mills EJ, et al. Reanalyses of randomized clinical trial data. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1024–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.9646.

Oelke M. Leitlinien der Deutschen Urologen zur Therapie des benignen Prostatasyndroms (BPS). Der Urologe A. 2003;42(5):722–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00120-003-0318-3.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthias Herpers and Joanna Schindler from ClinStat GmbH for their essential support of the statistical analysis and interpretation of the integrated results.

Funding

Omega Pharma Manufacturing GmbH & Co. KG funded the investigation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: WV, SH, BP; Methodology: KS, BP; Software, validation, formal data analysis: KS; Resources (providing original study reports and data listings) & Funding acquisition: SH; Writing the original draft manuscript: BP, KS; Reviewing & Editing: WV, KS, BP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Winfried Vahlensieck received financial support from Omega Pharma Manufacturing GmbH & Co. KG for investigations related to the formerly published GRANU study. Stefan Heim is an employee of Omega Pharma Manufacturing GmbH & Co. KG. Brigitte Patz acts as a consultant for Omega Pharma Manufacturing GmbH & Co. KG. Dr. Kurtulus Sahin is CEO of ClinStat GmbH, Institute of Clinical Research and Statistics, which received payment from Omega Pharma Manufacturing GmbH & Co KG for analysis.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table A.

Eligibility criteria, efficacy, and safety variables of the studies. Supplementary Table B. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the PP set. Supplementary Table C. Mean IPSS change from baseline at all visits and differences between treatment groups after 12 months (PSE minus placebo), ITT set using LOCF. Supplementary Table D. IPSS QoL scores and changes from baseline at all visits (ITT set).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vahlensieck, W., Heim, S., Patz, B. et al. Beneficial effects of pumpkin seed soft extract on lower urinary tract symptoms and quality of life in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a meta-analysis of two randomized, placebo-controlled trials over 12 months. Clin Phytosci 8, 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40816-022-00345-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40816-022-00345-0