Abstract

Background

Acute bronchitis, frequently emerging with the common cold is one of the most frequent causes of primary care consultations. It is a self-limiting disease which poses both high symptom burden to individuals and high financial burden to society. It is largely a viral disease (~50 % rhinovirus infection), but no causal (antiviral) treatment exists. Antibiotics, mucoactive agents, antihistamines, antitussives, decongestants are most often used but without evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCT) for relieving symptoms or fostering recovery.

Many in vitro and ex vivo studies with standardized herbal extracts did show important effects on inflammatory mediators, mucus hypersecretion, cough and bronchospasm. Moreover, several successful clinical RCT’s with unique herbal compounds were published, many other are ongoing.

Methods

Preliminary medline search for randomized controlled studies with herbal medicine for bronchitis.

Results

Eighteen studies were found fulfilling search criteria; six were excluded due to duplicate publication, active comparator control or open design. In 2015 German cough guidelines (in preparation) at least 12 studies will provide evidence for developing recommendations for treatment of acute bronchitis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, several herbal compounds achieved as first pharmaco-therapeutic remedies at all evidence for treatment of acute bronchitis/common cold. Evidence based guidelines are starting to include recommendations for treatment of acute bronchitis/common cold with dedicated phytomedicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute bronchitis is an inflammatory disease of the tracheobronchial system, clinically characterized by cough with or without sputum production. In their New England Journal review Wenzel et al. define: “Acute bronchitis is a clinical term implying a self-limited inflammation of the large airways of the lung that is characterized by cough without pneumonia.”[1]. However, according to the American College of Chest Physician guidelines acute cough is also one of the main symptoms of common cold: …the clinical syndrome of nasal congestion, nasal discharge, postnasal drip (PND), throat clearing, sneezing, and cough is common to all of these infections.” [2]. It is largely recognized that distinguishing between acute cough due to acute bronchitis and/or common cold is not practicable: “The prevalence of cough due to the common cold is as high as 83 % within the first two days of illness and because the common cold and acute bronchitis share many of the same symptoms the clinical distinction between acute and chronic bronchitis and the common cold is difficult, or at times, impossible to make.”[3]. This problem is well recognized not only in guidelines, but also in clinical papers [4] and RCT reports [5].

Indeed, in a retrospective study Hueston et al. investigated how to best distinguish between acute bronchitis and common cold and concluded: “…there was considerable overlap between the 2 conditions, and the logistic model explained only 37 % of the variation between the diagnoses. Conclusions: We hypothesize that sinusitis, URI, and acute bronchitis are all variations of the same clinical condition (acute respiratory infection)…” [6].

“Acute bronchitis is one of the most common reasons for patient visits to ambulatory care or physicians. Frequently, it develops during the course of a common cold with a predominant symptom of dry or productive cough.” [5].

Acute bronchitis in otherwise healthy adults is a self-limiting disease with an average duration of the main symptom cough of 14 days [4]. In children, however acute cough can last an average of 25 days [7]. Nonetheless, cough guidelines [8–10] define acute cough lasting as long as up to eight weeks – under some circumstances, i.e., if elicited by adenovirus, mycoplasma pneumoniae or Bordatella pertussis infection. Some people are using the definition of subacute cough [11], lasting 3–8 weeks.

After eight weeks of duration, cough/bronchitis will be defined as chronic. In contrast to acute bronchitis beyond history and clinical exam further diagnostic measures (i.e., chest x-ray and spirometry) are considered necessary in chronic bronchitis .

Acute bronchitis, caused largely by viruses (~50 % rhinovirus infection), no causal (antiviral) treatment exists. Despite being a self limiting disease, acute bronchitis poses both a high symptom burden to individuals and a high financial burden to society, mainly due to work and school absenteeism. Moreover, in the community, up to 85 % of cases of acute bronchitis are treated with antibiotics – with little impact on recovery [12]. Unnecessary and uncontrolled use of antibiotics in acute bronchitis contributes to an impending doom of antibiotic resistance [13].

As yet no RCT based evidence exists for synthetic drugs as opposed to herbal compounds for acute bronchitis. Yet, in randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) largely used older, patent-free synthetic substances i.e., muco-active drugs, antitussives, antihistamines, NSAR (non-steroidal anti-rheumatics) with a distinct straightforward pathophysiological target do not have proven clinical benefit vs. placebo [14].

Six thousand years B.C. the old Egyptians already used plants to treat ailments, thus many centuries empirical knowledge was collected on use of herbal remedies. As yet, the majority of phytotherapeutics in use in the European community is approved merely based on such empirical knowledge. At the very end of the XX. century however, in medicine evidence based scientific guidelines were introduced and new approvals request scientific evidence of efficacy. There are different tools in use for assessment of evidence and for generating recommendations, but all those systems require controlled trials to show efficacy against placebo or at least a proven comparator drug. For evidence based recommendation (and for approval) adverse events and real world effectiveness are also taken into account. But popularity and low rates of adverse events are not sufficient for guideline recommendations.

Recently some standardized herbal extracts in RCT’s were proven effective against placebo relieving symptom burden and fostering recovery in acute bronchitis. (Another field of phytotherapy in bronchitis - beyond the scope of this article - is the prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) on top of guideline based treatments beside long acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids).

This article shall define the evidence base of some herbal therapeutics in the treatment of acute bronchitis.

Guidelines on cough

The first German evidence based guidelines for cough were published 2004 [15]. At that time, literature search could not reveal randomized controlled trials with acceptable methodology for treatment of acute bronchitis [1]. Thus, no recommendation for pharmacological therapy was given. This result was little surprising according to many methodological pitfalls for RCT’s in acute bronchitis (with or without common cold):

-

1.

In a self-limiting disease (i.e., acute bronchitis) with an average duration of the main symptom cough of merely 14 days even effective treatments can only reduce duration or severity of symptoms if timely introduced.

-

2.

many patients are not seeking medical attention, limiting recruitment to RCT’s

-

3.

Every pharmacotherapy of acute bronchitis has a huge placebo effect [16]

-

4.

In the past, no outcomes in acute bronchitis trials were agreed upon

-

5.

most if not all bronchitis remedies were available as over the counter (OTC) generics. Hence, sponsoring of sufficiently large clinical trials was not obtainable.

In 2010, an update of the German cough Guidelines was published [8]. In 2009, the literature search identified RCT’s showing efficacy shortening symptoms of acute bronchitis for two herbal combinations [17, 18] graded as moderate evidence leading to a strong recommendation for treatment of acute bronchitis with the proven combinations.

Methods and results

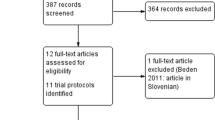

For the 2015 update of the German cough guidelines I performed a preliminary search in medline for trials with herbal medicine in acute bronchitis. In December 2014 using search terms (bronchitis AND herbal; bronchitis AND phytomedicine; bronchitis AND phytotherapy; common cold AND herbal; common cold AND phytomedicine; common cold AND phytotherapy) each in title and abstract resulted in 185 hits, subtracting duplicate hits remained 143 results. According to the abstracts in this preliminary search about 18 controlled trials for acute bronchitis outcomes were found. According to duplicate publications of the same trial and active control noninferiority trials we show in Table 1 the preliminary results with 12 studies [17–28]. Moreover, data from publication 25 were also separately published for Russian centres (26).

Only four different remedies were proven in adults and in children in these studies: EPs7630, two different combinations of thyme and primrose, one of thyme and ivy and another of myrtol. I did not include many double-blind non-inferiority active comparator controlled studies, if efficacy of “active control” was not proven, e.g., [29, 30]. All (published) double-blind RCT’s showing significant efficacy over placebo. However, publication bias cannot be excluded. Final evidence tables with the 2015 update of the guideline will be published later.

Nowadays getting RCT’s sponsored for herbal remedies is feasible as the proven evidence is related not to a plant or a combination of plants but only to the proven, unique remedy (see dot 5 above). Efficacy of herbal compounds is highly dependent on the plants used, extraction and standardization methods. Results of clinical trials for a distinct preparation cannot be transferred for other preparations using the same plant or combination of plants. Many patented herbal remedies are available for trials and treatment. Moreover, for acute bronchitis/common cold, a 15 years old tool, BSS (bronchitis severity scale) is now a validated outcome measure [31, 32]. Also recommendations for cough monitoring now exist [10]. Thus, in contrast to synthetic drugs, each herbal compound needs independent RCT’s for proof of efficacy. For new approvals EMA (European Medicine Agency) and FDA (Food and Drug Administration) require replicate RCT’s.

Discussion

Even if common cold/acute bronchitis are self limiting conditions, there is still a large unmet need for effective therapy relieving patients symptoms and shortening the course of disease with impact on the huge epidemiological burden acute bronchitis posing on the society. In contrast to many other frequent diseases i.e., coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, tumors etc., common cold/acute bronchitis affects mainly the young working population.

As yet few pharmacotherapeutic options are evidence based for the treatment of acute bronchitis, unless one acknowledges the “evidence” that billions of euros and dollars are spent for OTC drugs, i.e., expectorants, decongestants, antitussives [33] without RCT-proven effects on the natural history of the disease or symptoms. Moreover, the vast majority of patients with common cold/acute bronchitis consulting a physician takes ineffective prescription antibiotics for their viral disease resulting in a recent marked increase in antibiotic resistance in the community.

Common cold/acute bronchitis is a complex inflammatory disease. Single pathomechanistic approaches to treatment may be not effective. For example, even useful antiviral treatment of influenza, a myxovirus infection, with neuramidase blockers has limited activity on symptoms and is only effective if given in the first 48 h after onset of fever. Current debate on the efficacy of oseltamivir shows how complex is conducting RCT’s in a self-limiting viral disease [34]. Viral infections in common cold (~50 % of those are due to rhinoviruses) of the respiratory epithelium causes early release of many inflammatory mediators sensitizing chemosensitive cough receptors. Moreover, epithelial shedding, leaving cough receptors unprotected and vulnerable for even innocuous inhalative physical stimuli such as changing temperature, also enhances the cough reflex eliciting dry cough.

Mucus hypersecretion by superficial goblet cells is responsible for wet cough, a characteristic of the first few days of the viral infection. Mucociliary clearance is also affected both by inflammatory cytokines and changes in mucus viscosity. The inflammatory edema of the mucosa causes paranasal sinus pain and/or increase in resistance of the upper (nasal stuffiness) and lower airways. Moreover, in bronchial hyperresponsive patients, asthma (bronchospasm) can be exacerbated.

Beyond systemic corticosteroids with broad anti-inflammatory effects no single synthetic drug is known having an effect on most patho- physiological components as shown above. In contrast, in a myriad of in vitro and ex vitro studies, important effects on several components of the pathophysiology by single and composite herbal extracts are published, e.g., [35–44]. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss their results. Importantly, those basic results generate hypotheses for clinical trials of herbal drugs for common cold/acute bronchitis.

Conclusion

As yet, very few evidence based treatments for one of the the most frequent illnesses, common cold/acute bronchitis are available. High symptom and societal burden justify intensive research for new evidence based effective pharmacotherapies for this self-limiting disease with multifaceted pathophysiology. High quality, standardized herbal compounds with their broad pharmacologic effects are probably the most promising approach to treat common cold. In the near future sophisticated cultivating of eligible plants and extraction/standardization methods (bioengineering) will allow production of targeted phytotherapeutics. In fact, several RCT-proven compounds are already available. Phytopharmaca are generally well tolerated and highly accepted by patients. Phytopharmaca are also promising in broadening indication (e.g., subacute cough, postviral rhinosinusitis) or even prevention of COPD exacerbations.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive lung disease

- EMA:

-

European Medicine Agency

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration (USA)

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Wenzel RP, Fowler III AA. Clinical practice. Acute bronchitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2125–30.

Pratter MR. Cough and the common cold: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:72S–4S.

Braman SS. Chronic cough due to acute bronchitis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:95S–103S.

Albert RH. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1345–50.

Fischer J, Dethlefsen U. Efficacy of cineole in patients suffering from acute bronchitis: a placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Cough. 2013;9:25.

Hueston WJ, Mainous III AG, Dacus EN, Hopper JE. Does acute bronchitis really exist? A reconceptualization of acute viral respiratory infections. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:401–6.

Matthew T, Vodicka TA, Blair PS, Buckley DI, Heneghan C, Hay AD, et al. Duration of symptoms of respiratory tract infections in children: systematic review. BMJ. 2013;347:f7027.

Kardos P, Berck H, Fuchs KH Gillissen A, Klimek L, Morr H. Guidelines of the German Respiratory Society for Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults Suffering from Acute or Chronic Cough. Pneumologie. 2010;64(11):701–11.

Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, Boulet LP, Braman SS, Brightling CE, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:1S–23S.

Morice AH, Fontana GA, Sovijarvi AR, Pistolesi M, Chung KF, Widdicombe J, et al. The diagnosis and management of cough. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:481–92.

Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364–74.

Butler CC, Hood K, Verheij T, Little P, Melbye H, Nuttall J, et al. Variation in antibiotic prescribing and its impact on recovery in patients with acute cough in primary care: prospective study in 13 countries. BMJ. 2009;338:b2242.

Antibiotic resistance: a final warning. Lancet. 2013;382:1072.

Lee PC, Jawad MS, Hull JD, West WH, Shaw K, Eccles R. The antitussive effect of placebo treatment on cough associated with acute upper respiratory infection. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:314–7.

Kardos P, Cegla U, Gillissen A, Kirsten D, Mitfessel H, Morr H, et al. Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie zur Diagnostik und Therapie von Patienten mit akutem und chronischem Husten. Pneumologie. 2004;58:570–602.

Eccles R. Importance of placebo effect in cough clinical trials. Lung. 2010;188:S53–61.

Kemmerich B. Evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination of dry extracts of thyme herb and primrose root in adults suffering from acute bronchitis with productive cough. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2007;57:607–15.

Kemmerich B, Eberhardt R, Stammer H. Efficacy and tolerability of a fluid extract combination of thyme herb and ivy leaves and matched placebo in adults suffering from acute bronchitis with productive cough. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2006;56:652–60.

Gillissen A, Wittig T, Ehmen M, Krezdorn HG, de Mey C. A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial on the efficacy and tolerability of GeloMyrtol(R) forte in acute bronchitis. Drug Res (Stuttg). 2013;63:19–27.

Kamin W, Maydannik VG, Malek FA, Kieser M. Efficacy and tolerability of EPs 7630 in patients (aged 6–18 years old) with acute bronchitis. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:537–43.

Kamin W, Maydannik V, Malek FA, Kieser M. Efficacy and tolerability of EPs 7630 in children and adolescents with acute bronchitis - a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial with a herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides roots. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:184–91.

Kamin W, Ilyenko LI, Malek FA, Kieser M. Treatment of acute bronchitis with EPs 7630: randomized, controlled trial in children and adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:219–26.

Matthys H, Lizogub VG, Malek FA, Kieser M. Efficacy and tolerability of EPs 7630 tablets in patients with acute bronchitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-finding study with a herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1413–22.

Matthys H, Funk P. EPs 7630 improves acute bronchitic symptoms and shortens time to remission. Results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Planta Med. 2008;74:686–92.

Matthys H, Heger M. Treatment of acute bronchitis with a liquid herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides (EPs 7630): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:323–31.

Chuchalin AG, Berman B, Lehmacher W. Treatment of acute bronchitis in adults with a pelargonium sidoides preparation (EPs 7630): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Explore (NY). 2005;1:437–45.

Matthys H, Eisebitt R, Seith B, Heger M. Efficacy and safety of an extract of Pelargonium sidoides (EPs 7630) in adults with acute bronchitis. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2003;10 Suppl 4:7–17.

Gruenwald J, Graubaum HJ, Busch R. Efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination of thyme and primrose root in patients with acute bronchitis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2005;55:669–76.

Gruenwald J, Graubaum HJ, Busch R. Evaluation of the non-inferiority of a fixed combination of thyme fluid- and primrose root extract in comparison to a fixed combination of thyme fluid extract and primrose root tincture in patients with acute bronchitis. A single-blind, randomized, bi-centric clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2006;56:574–81.

Cwientzek U, Ottillinger B, Arenberger P. Acute bronchitis therapy with ivy leaves extracts in a two-arm study. A double-blind, randomised study vs. an other ivy leaves extract. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:1105–9.

Kardos P, Lehrl S, Kamin W, Matthys H. Assessment of the effect of pharmacotherapy in common cold/acute bronchitis - the Bronchitis Severity Scale (BSS). Pneumologie. 2014;68:542–6.

Lehrl S, Matthys H, Kamin W, Kardos P. The BSS - a valid clinical instrument to measure the severity of acute bronchitis. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2014;1:00016–25.

Walmsley J, Marshall G. Over the counter cough medicines for acute cough. The fact that people keep buying the medicines is itself evidence. BMJ. 2002;324:1158.

Hsu J, Santesso N, Mustafa R, Brozek J, Chen YL, Hopkins JP, et al. Antivirals for treatment of influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):512–24.

Glatthaar-Saalmuller B, Rauchhaus U, Rode S, Haunschild J, Saalmüller A. Antiviral activity in vitro of two preparations of the herbal medicinal product Sinupret(R) against viruses causing respiratory infections. Phytomedicine. 2011;19:1–7.

Juergens UR, Stober M, Schmidt-Schilling L, Kleuver T, Vetter H. Antiinflammatory effects of euclyptol (1.8-cineole) in bronchial asthma: inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolism in human blood monocytes ex vivo. Eur J Med Res. 1998;3:407–12.

Juergens UR, Stober M, Vetter H. The anti-inflammatory activity of L-menthol compared to mint oil in human monocytes in vitro: a novel perspective for its therapeutic use in inflammatory diseases. Eur J Med Res. 1998;3:539–45.

Neugebauer P, Mickenhagen A, Siefer O, Walger M. A new approach to pharmacological effects on ciliary beat frequency in cell cultures--exemplary measurements under Pelargonium sidoides extract (EPs 7630). Phytomedicine. 2005;12:46–51.

Juergens UR, Dethlefsen U, Steinkamp G, Gillissen A, Repges R, Vetter H. Anti-inflammatory activity of 1.8-cineol (eucalyptol) in bronchial asthma: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Respir Med. 2003;97:250–6.

Morice AH, Marshall AE, Higgins KS, Grattan TJ. Effect of inhaled menthol on citric acid induced cough in normal subjects. Thorax. 1994;49:1024–6.

Kenia P, Houghton T, Beardsmore C. Does inhaling menthol affect nasal patency or cough? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:532–7.

Wise PM, Breslin PA, Dalton P. Sweet taste and menthol increase cough reflex thresholds. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25:236–41.

Buday T, Brozmanova M, Biringerova Z, Gavliakova S, Poliacek I, Calkovsky V, et al. Modulation of cough response by sensory inputs from the nose - role of trigeminal TRPA1 versus TRPM8 channels. Cough. 2012;8:11.

Plevkova J, Kollarik M, Poliacek I, Brozmanova M, Surdenikova L, Tatar M, et al. The role of trigeminal nasal TRPM8-expressing afferent neurons in the antitussive effects of menthol. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013;115:268–74.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Eva Kugler, Department Clinical research International Bionorica SE, Neumarkt, Germany who assisted in preparing table one of the article based on author’s direction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

PK gave presentations at symposia and/or served on scientific advisory boards sponsored by AstraZeneca, Bionorica, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Novartis, Takeda and Dr. Wilmar Schwabe.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kardos, P. Phytotherapy in acute bronchitis: what is the evidence?. Clin Phytosci 1, 2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40816-015-0003-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40816-015-0003-2