Abstract

Objectives

To outline the planning, development and optimisation of a psycho-educational behavioural intervention for patients on active surveillance for prostate cancer. The intervention aimed to support men manage active surveillance-related psychological distress.

Methods

The person-based approach (PBA) was used as the overarching guiding methodological framework for intervention development. Evidence-based methods were incorporated to improve robustness. The process commenced with data gathering activities comprising the following four components:

• A systematic review and meta-analysis of depression and anxiety in prostate cancer

• A cross-sectional survey on depression and anxiety in active surveillance

• A review of existing interventions in the field

• A qualitative study with the target audience

The purpose of this paper is to bring these components together and describe how they facilitated the establishment of key guiding principles and a logic model, which underpinned the first draft of the intervention.

Results

The prototype intervention, named PROACTIVE, consists of six Internet-based sessions run concurrently with three group support sessions. The sessions cover the following topics: lifestyle (diet and exercise), relaxation and resilience techniques, talking to friends and family, thoughts and feelings, daily life (money and work) and information about prostate cancer and active surveillance. The resulting intervention has been trialled in a feasibility study, the results of which are published elsewhere.

Conclusions

The planning and development process is key to successful delivery of an appropriate, accessible and acceptable intervention. The PBA strengthened the intervention by drawing on target-user experiences to maximise acceptability and user engagement. This meticulous description in a clinical setting using this rigorous but flexible method is a useful demonstration for others developing similar interventions.

Trial registration and Ethical Approval

ISRCTN registered: ISRCTN38893965. NRES Committee South Central – Oxford A. REC reference: 11/SC/0355

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Key messages regarding feasibility

-

At the start of this process, there were uncertainties around the feasibility of:

-

Reaching and recruiting the target group (men on active surveillance for prostate cancer)

-

Creating an accessible and acceptable intervention

-

-

Key feasibility findings:

-

Men on active surveillance for prostate cancer would like additional support and are willing to take part in online and group-based sessions

-

-

The research activities carried out in the intervention planning and development phases have optimised the acceptability of the proposed intervention.

Background

Prostate cancer prevalence is high in the UK [1] and affects around one in eight men [2]. Treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy and hormone therapy, but for men with localised, low-risk prostate cancer, active surveillance (AS), a pathway that involves monitoring biological markers of the disease for progression, is also an option. AS aims to reduce overtreatment and comes without the unwanted side effects of interventional treatment, such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction [3]. However, research has shown AS may have a negative impact on psychological wellbeing with patients experiencing heightened levels of anxiety [4,5,6], illness uncertainty, hopelessness [7] and distress [8].

Few studies have explored the unmet psychological needs of men on AS and ways in which wellbeing could be improved [9], and to our knowledge, there are no existing interventions available to support men on AS. The limited qualitative evidence suggests men on AS find AS-related information inadequate and inconsistent [9] and experience unmet psychological and emotional needs [9], and spousal support is important for AS acceptance [10]. Furthermore, anxiety and uncertainty are two key reasons men choose to discontinue AS and pursue interventional treatments in the absence of changes to tumour status [11, 12], risking treatment side effects. Research in the area of AS-related psychological wellbeing is vital to ensure patients have the information and tools that will allow them to better cope with this treatment pathway.

Best practice guidance recommends taking a ‘person-based’ approach (PBA) when developing behavioural interventions [13]. The PBA is an established method used to optimise interventions, providing a clear process to ground interventions in the perspectives and psychosocial context of the target user group. The PBA recommends comprehensive qualitative research with the target user group to explore their experiences and create a picture of the challenges they face, and in turn the things that are likely to influence a target behaviour. Exploration of the key beliefs target users hold, for example, about their condition, its management or treatment, is important to gain an understanding of what might facilitate or prevent change. Taking this approach, the target users’ needs and preferences can influence the content, structure and overall design of the intervention, ultimately improving the intervention’s feasibility, acceptability and user engagement [14]. Intervention developers are utilising PBA techniques increasingly [15,16,17]; however, there is a lack of literature providing replicable, worked examples of intervention development using the PBA.

This paper describes four previously published research activities, bringing them together to demonstrate how they contributed to the planning and development process of PROACTIVE, a psycho-educational intervention for men with localised prostate cancer on active surveillance, consisting of parallel group-support and web-based sessions. It aims to describe the methodology needed to plan such an intervention, presenting a demonstration of how to develop an intervention using a PBA. The resulting intervention has been trialled in a feasibility study, the results of which are published elsewhere [18].

Methods

Using the person-based approach to guide PROACTIVE planning

The PBA is flexible and non-prescriptive and can be utilised alongside evidence-based approach methods and theory. The PBA provides an established methodological framework for the intervention planning process [13].The approach consists of two key stages. The first involves gathering information from the target audience to gain an insight into what is wanted and needed, giving the researchers a deeper appreciation of the psychosocial context of the audience. This is an iterative process used to continually refine the intervention to promote acceptability and to encourage adherence and engagement.

The second stage is the creation of ‘key guiding principles’. These consist of (a) key intervention design objectives and (b) key distinctive features of the intervention needed to achieve objectives. These principles aim to keep the design and development process on track by providing the research team with a summary of objectives to be referred to at each stage of the process.

The planning process commenced with a systematic review and meta-analysis of depression and anxiety in PCa. This was an evidence gathering activity aiming to improve understanding about the prevalence and magnitude of psychological distress in men with PCa (not specific to AS).

Using the PBA framework, the following activities were subsequently conducted to facilitate our understanding of psychological distress specific to those on the AS pathway, the interventions that have been trialled previously and the supportive care needs of the target audience:

-

A cross-sectional survey on depression and anxiety in active surveillance

-

A review of existing interventions in the field

-

A qualitative study with the target audience

These components facilitated the creation of key guiding principles and a logic model to guide the intervention development.

Table 1 shows the stages recommended by the PBA for intervention planning and development (columns 1 and 2) alongside an overview of the development of PROACTIVE (column 3) to show how the PBA process was implemented. Each activity will be described in depth in the next section.

Intervention planning

In this section of the paper, we describe the data gathering activities we undertook to consolidate our understanding of the issue (reduced psychological wellbeing in men on AS for PCa), and accumulate ideas about what might be helpful to this population. Table 2 provides an overview of these activities.

Intervention design

In this section of the paper, we describe how the data gathered in the ‘Intervention planning’ section was used to design the intervention, and how the creation of the ‘key guiding principles’ and ‘logic model’ facilitated this process.

Key guiding principles

Using the information gathered during the intervention planning phase, the research team developed a set of key guiding principles, in line with the PBA approach. The purpose of this is to summarise the design objectives and how these will be achieved, to facilitate quick and easy reference throughout the planning and development phase to guide and focus the decision making around intervention content and design [13]. Table 5 outlines the three intervention design objectives along with the key features of the intervention designed to address each objective.

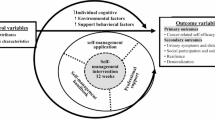

Developing a logic model

The MRC complex intervention guidelines [38] recommend the development of a logic model to outline the hypothesised causal mechanisms involved in bringing about change in men on AS for PCa. The logic model (Fig. 1) demonstrates how we anticipate the intervention will result in improved psychological wellbeing.

Public and patient involvement.

Three patient and public involvement (PPI) contributors with PCa were involved in the intervention planning and development process. The research team met with the contributors every 4–8 weeks to provide progress updates and gain feedback on ideas and written materials. PPI contributors reviewed and commented on the online and workshop content and were involved in all key decisions. The involvement of the PPI contributors ensured developing study materials were likely to be acceptable, understandable and relevant to the target audience.

Results

The PROACTIVE prototype

The prototype intervention was named PROACTIVE – ‘PROstate ACTIVE surveillance support’. The intervention consisted of two parts:

-

1)

An online programme consisting of six sessions designed to be completed on a weekly basis.

-

2)

A face-to-face group support programme with three sessions, spread across six weeks, held fortnightly and each lasting 60–90 min.

The web-based programme and the group support sessions interlink and are designed to run in parallel over 6 weeks, complementing each other; for example, the online sessions introduce topics that will be further discussed in the following group session, and the online sessions reinforce the information covered in previous group sessions. Figure 2 shows the intervention as a whole over the 6 week time period. See Table 6 for a detailed description of the session content.

The intervention

Table 6 details the content of each of the web-based and face-to-face group sessions delivered over the 6-week period.

Think aloud interviews to refine PROACTIVE

Identified by the PCaSO charity (Prostate Cancer Support Organisation), 2 men with prostate cancer took part in think aloud interviews. This process involved each participant working their way through the PROACTIVE prototype whilst simultaneously speaking aloud their thoughts about the programme. Statements such as ‘can you tell me what you think about this page?’ and ‘can you tell me why you chose that option?’ were used as prompts to elicit participants’ opinions on the intervention. Interviews were audio recorded, and participants’ thoughts and opinions were collated and used to amend the prototype to be used in the feasibility study. Table 7 provides a summary of these changes.

PROACTIVE ready for feasibility study

The amended intervention became the final version for the feasibility study. Figure 3 shows some screenshots from the web-based sessions.

The feasibility study has been conducted, and the results published elsewhere [18].

Discussion

Summary

This paper demonstrates how we used the PBA to develop an Internet- and group-based psycho-educational behavioural intervention for men on AS for PCa. The process of gathering, understanding and utilising target-user needs and perspectives has long been viewed as essential within the eHealth research community [39,40,41]. Intervention developers in the area of eHealth have undertaken this task in a variety of ways [42, 43]; however, until the publication of the PBA, there was no standardised approach or process to follow. Guided by the PBA, the researchers gained a context-specific understanding of the intervention elements likely to be needed to maximise participant acceptability and engagement.

Each component of our approach (see Table 1) added a valuable contribution to the development process. The systematic review and meta-analysis of depression and anxiety in prostate cancer provided a broad understanding of the prevalence of these conditions in PCa patients, and confirmed the dearth of literature specific to AS. Beginning to fill this gap in the literature, the cross-sectional survey on depression and anxiety in AS allowed us to narrow down the treatment pathway diversity in previous studies and focus on men on AS. Men in this survey displayed significant levels of distress, reinforcing the value of the proposed intervention. Reviewing existing interventions in the field provided a way of seeing what has and has not been successful in the past, and an understanding of the elements that may increase the success of the proposed intervention. The qualitative study gave us the opportunity to explore the supportive care needs of this user group in an in-depth way providing focussed direction for the intervention and a way of identifying any gaps.

Integrating the results from these 4 components we were able to create a set of key guiding principles. The key guiding principles summarised the design objectives and provided focus for decision making. Our logic model provided a visual representation of how the intervention might work, displaying the intervention ingredients and how these translate into the causal mechanisms likely to bring about change.

Armed with the understanding gained from the abovementioned processes, we were able to create the prototype PROACTIVE intervention. The think-aloud interviews provided further clarity, and the minor changes made due to the results of these interviews improved our confidence in the intervention.

This methodological approach is rigorous but flexible. For other interventions, the stages and processes may differ depending on the context of the intervention [15, 16, 44, 45], for example, if there is already a large base of existing qualitative research, new qualitative research may not be necessary.

Strengths, limitations and future research

Treatment for PCa is a rapidly changing and advancing field, for example, medical technology and the accuracy of diagnostic tests continually being improved. For this reason PCa interventions (including PROACTIVE) would need to be updated regularly to stay current and accurate. The advantage of this development process is that it has produced a core product based on a rigorous transparent process with clear guiding principles that can easily be shared, adapted and updated, negating the need to repeatedly start from scratch.

The PBA recommends incorporating behavioural science into the development of interventions by integrating a ‘theory-based’ approach with the PBA processes as best practice. In this instance, this was not possible due to time and resource constraints. Further research conducting theory-based processes, and mapping the findings to the intervention, identifying any gaps, would be beneficial to potentially strengthen the intervention.

Conclusion

This paper outlines the stages we followed using the PBA to develop the PROACTIVE intervention. The planning and development process is key to successful delivery of an appropriate accessible intervention. This meticulous description in a clinical setting using this rigorous but flexible method is a useful demonstration for others developing similar interventions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

References

Smittenaar CR, Petersen KA, Stewart K, Moitt N. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(9):1147–55.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Bergh R, Randsdorp H, Repetto C, Venderbos LD, et al. How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review Eur Urol. 2015;67(4):637–45.

Watts S, Leydon G, Birch B, Prescott P, Lai L, Eardley S, et al. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e003901.

Watts S, Leydon G, Eyles C, Moore CM, Richardson A, Birch B, et al. A quantitative analysis of the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety in patients with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e006674.

Taylor KL, Hoffman RM, Davis KM, Luta G, Leimpeter A, Lobo T, et al. Treatment preferences for active surveillance versus active treatment among men with low-risk prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(8):1240.

Biddle S. The psychological impact of active surveillance in men with prostate cancer: implications for nursing care. Br J Nurs. 2021;30(10):S30–7.

Watts S. The assessment and management of anxiety and depression in prostate cancer patients being managed with active surveillance. Southampton: University of Southampton; 2014.

McIntosh M, Opozda MJ, Evans H, Finlay A, Galvao DA, Chambers SK, et al. A systematic review of the unmet supportive care needs of men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(12):2307–22.

Donachie K, Cornel E, Adriaansen M, Mennes R, Oort I, Bakker E, et al. Optimizing psychosocial support in prostate cancer patients during active surveillance. Int J Urol Nurs. 2020;14(3):115–23.

Parker PA, Davis JW, Latini DM, Baum G, Wang X, Ward JF, et al. Relationship between illness uncertainty, anxiety, fear of progression and quality of life in men with favourable-risk prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BJU Int. 2016;117(3):469–77.

Latini DM, Hart SL, Knight SJ, Cowan JE, Ross PL, Duchane J, et al. The relationship between anxiety and time to treatment for patients with prostate cancer on surveillance. J Urol. 2007;178(31):826–31 (discussion 31-2).

Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e30.

Yardley L, Ainsworth B, Arden-Close E, Muller I. The personbased approach to enhancing the acceptability and feasibility of interventions. 2015.

Band R, Bradbury K, Morton K, May C, Michie S, Mair FS, et al. Intervention planning for a digital intervention for self-management of hypertension: a theory-, evidence- and person-based approach. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):25.

Band R, Hinton L, Tucker KL, Chappell LC, Crawford C, Franssen M, et al. Intervention planning and modification of the BUMP intervention: a digital intervention for the early detection of raised blood pressure in pregnancy. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:153.

Bradbury K, Steele M, Corbett T, Geraghty AWA, Krusche A, Heber E, et al. Developing a digital intervention for cancer survivors: an evidence-, theory- and person-based approach. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2:85.

Hughes JG, Leydon GM, Watts S, et al. A feasibility study of a psycho-educational support intervention for men with prostate cancer on active surveillance. Cancer Reports. 2019;e1230.

van den Bergh RC, Essink-Bot ML, Roobol MJ, Wolters T, Schroder FH, Bangma CH, et al. Anxiety and distress during active surveillance for early prostate cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(17):3868–78.

Van den Bergh R, Essink-Bot ML, Robol MJ, Schroder FH, Bangma C, Steyerberg EW. Do anxiety and distress increase during active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer? J Urol. 2010;183:1786–91.

Burnet KL, Parker C, Dearnaley D, Brewin CR, Watson M. Does active surveillance for men with localized prostate cancer carry psychological morbidity? BJU Int. 2007;100(3):540–3.

Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Dickman PW, Johansson JE, Norlén BJ, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):790–6.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1982;67:361–70.

NHS: The Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Health Survey for England 2005: Health of Older People. 2007.

Parker PA, Pettaway CA, Babaian RJ, Pisters LL, Miles B, Fortier A, et al. The effects of a presurgical stress management intervention for men with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3169–76.

Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Molton I, Gonzalez JS, Kinsinger D, Roos BA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management improves stress-management skills and quality of life in men recovering from treatment of prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(1):192–200.

Penedo FJ, Molton I, Dahn JR, Shen BJ, Kinsinger D, Traeger L, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(3):261–70.

Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):571–81.

Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(8):1038–49.

Templeton H, Coates V. Evaluation of an evidence-based education package for men with prostate cancer on hormonal manipulation therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55(1):55–61.

Berglund G, Petersson LM, Eriksson KC, Wallenius I, Roshanai A, Nordin KM, et al. “Between Men”: a psychosocial rehabilitation programme for men with prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(1):83–9.

Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, Schulz R. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):443–52.

Bailey DE, Mishel MH, Belyea M, Stewart JL, Mohler J. Uncertainty intervention for watchful waiting in prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(5):339–46.

Chambers SK, Ferguson M, Gardiner RA, Aitken J, Occhipinti S. Intervening to improve psychological outcomes for men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):1025–34.

Kazer MW, Bailey DE Jr, Sanda M, Colberg J, Kelly WK. An Internet intervention for management of uncertainty during active surveillance for prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(5):561–8.

Osei DK, Lee JW, Modest NN, Pothier PK. Effects of an online support group for prostate cancer survivors: a randomized trial. Urol Nurs. 2013;33(3):123–33.

Weber BA, Roberts BL, Resnick M, Deimling G, Zauszniewski JA, Musil C, et al. The effect of dyadic intervention on self-efficacy, social support, and depression for men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(1):47–60.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–92.

Pagliari C. Design and Evaluation in eHealth: Challenges and Implications for an Interdisciplinary Field. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(2):e15.

Baker TB, Gustafson DH, Shah D. How can research keep up with eHealth? Ten strategies for increasing the timeliness and usefulness of eHealth research. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e36.

van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC, Nijland N, van Limburg M, Ossebaard HC, Kelders SM, Eysenbach G, et al. A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e111.

Van Velsen L, Wentzel J, Van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC. Designing eHealth that matters via a multidisciplinary requirements development approach. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2(1):e21.

Yen P-Y, Bakken S. Review of health information technology usability study methodologies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(3):413–22.

Morton K, Ainsworth B, Miller S, Rice C, Bostock J, Denison-Day J, et al. Adapting behavioral interventions for a changing public health context: a worked example of implementing a digital intervention during a global pandemic using rapid optimisation methods. Front Public Health. 2021;9:668197.

Muller I, Santer M, Morrison L, Morton K, Roberts A, Rice C, et al. Combining qualitative research with PPI: reflections on using the person-based approach for developing behavioural interventions. Res Involv Engagem. 2019;5:34.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Prostate Cancer UK for funding the study.

Professor George Lewith sadly passed away before publication. We would like to acknowledge him as the lead investigator for the PROACTIVE project. He is responsible for leading the team with design and development decisions.

Lastly, we would like to acknowledge Katherine Bradbury for offering advice and guidance with the Person-Based Approach.

Funding

Prostate Cancer UK, Grant/Award Number: PG14-023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH: Part of the team that designed and developed PROACTIVE. Created the PROACTIVE prototype website. Drafted the paper. AK: Part of the team that designed and developed PROACTIVE. Developed the content of the group sessions. Made substantial contributions to the paper with comments and advice. HE: Made substantial contributions to the paper with comments and advice. BS: Made substantial contributions to the paper with comments and advice. BB: Made substantial contributions to the paper with comments and advice. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hughes, S., Kassianos, A.P., Everitt, H.A. et al. Planning and developing a web-based intervention for active surveillance in prostate cancer: an integrated self-care programme for managing psychological distress. Pilot Feasibility Stud 8, 175 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-01124-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-01124-x