Abstract

Background

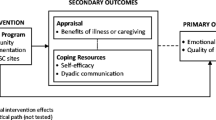

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates of any malignancy, placing a substantial burden on patients and families with high unmet informational and supportive care needs. Nevertheless, access to psychosocial and palliative care services for the individuals affected is limited. There is a need for standardized approaches to facilitate adjustment and to improve knowledge about the disease and its anticipated impact. In this intervention-development paper guided by implementation science principles, we report the rationale, methods, and processes employed in developing an interdisciplinary group psychoeducational intervention for people affected by pancreatic cancer. The acceptability and feasibility of implementation will be evaluated as a part of a subsequent feasibility study.

Methods

The Schofield and Chambers framework for designing sustainable self-management interventions in cancer care informed the development of the intervention content and format. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research served as an overarching guide of the implementation process, including the development phase and the formative evaluation plan of implementation.

Results

A representative team of stakeholders collaboratively developed and tailored the intervention content and format with attention to the principles of implementation science, including available resourcing. The final intervention prototype was designed as a single group-session led by an interdisciplinary clinical team with expertise in caring for patients with pancreatic cancer and their families and in addressing nutrition guidelines, disease and symptom management, communication with family and health care providers, family impact of cancer, preparing for the future, and palliative and supportive care services.

Conclusions

The present paper describes the development of a group psychoeducational intervention to address the informational and supportive care needs of people affected by pancreatic cancer. Consideration of implementation science during intervention development efforts can optimize uptake and sustainability in the clinical setting. Our approach may be utilized as a framework for the design and implementation of similar initiatives to support people affected by diseases with limited prognoses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies, with an overall 5-year survival rate of only 8%, and is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in North America [1, 2]. It is most often diagnosed at an advanced and incurable stage since early symptoms are largely absent [1]. The threat of impending mortality can be highly distressing and patients affected by this disease demonstrate higher rates of anxiety and depression than those with other types of cancers [3, 4]. Family members show similar or even greater levels of distress than their patient counterparts [5].

Those affected by pancreatic cancer have high informational and supportive care needs regarding symptom management, communication with health care providers (HCPs), worry about loved ones, and uncertainty about the future [6]. These needs are often unmet, despite clinical practice guidelines calling for psychosocial and educational support and for early palliative care [6,7,8]. This is consistent with evidence that the majority of patients with advanced cancer, including those with clinically significant psychological distress, are not referred for specialized psychosocial and palliative care [9,10,11,12]. This gap in health care may be related to stigma and misunderstanding about the potential benefit of psychosocial and palliative care services [13, 14], or limited accessibility and availability [15].

Psychoeducation refers to a treatment modality that provides information for self-management within a supportive social context and embeds both education and psychological care into routine care [16,17,18]. Systematic reviews of studies with mixed cancer populations have shown that there are significant and sustained benefits of psychoeducational interventions in relation to emotional distress and quality of life [19,20,21]. Psychoeducation has often been conceptualized as an intervention for patients with earlier stage cancer, but may be no less important for those with advanced disease [8]. Multidisciplinary psychoeducation programs may be well-suited to address the early information and support needs for people affected by pancreatic cancer, yet to date, there are no targeted psychoeducational interventions for this population.

We describe here the process of developing a psychoeducational intervention to address the informational and supportive care needs of people affected by pancreatic cancer, including patients and their loved ones, following an implementation science approach. Implementation science is an emerging field that examines the processes by which interventions can be tailored and optimized for specific clinical contexts [22]. The present paper details the development process, which is an earlier stage of activity prior to the conduct of a study of feasibility. By describing this process and how it is influenced by practical and contextual factors, we hope to provide guidance for scientists and clinicians seeking to implement similar initiatives in their settings.

Methods

We used the Schofield and Chambers [23] framework to inform the development of our intervention’s content and format. This framework seeks to promote effective and sustainable self-management interventions in cancer care. It emphasizes the targeting of interventions to cancer type and stage and tailoring them to individual needs. It also prioritizes evidence-based content, low-intensity delivery, and stakeholder acceptability.

We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) as an overarching guide of the whole implementation process [24]. The CFIR attends to five main domains: (I) intervention characteristics (e.g., evidence strength, and intervention quality and complexity); (II) the outer setting (i.e., external factors that may affect implementation, including the wider state of knowledge and policy climate); (III) the inner setting (i.e., internal organizational factors associated with readiness to implement); (IV) individual characteristics (e.g., personal attributes of stakeholders, beliefs about intervention, self-efficacy); and (V) the process of implementation itself, which includes planning and forethought, engaging champions, executing the plan, and evaluating the success of the intervention and implementation. CFIR encourages formative evaluation, which is “a rigorous assessment process designed to identify potential and actual influences on the progress and effectiveness of implementation efforts” [25]. Such evaluation allows continuous quality improvement in intervention content and delivery, spanning across the phases of development and implementation.

This report conforms to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist, which was developed to improve the completeness of reporting and replicability of interventions [26] [see Additional file 1].

Results

Stepwise development of the intervention

Evaluating the outer and inner setting

There has been global recognition of the importance of integrated supportive and palliative care throughout the illness trajectory from diagnosis to the end of life, as reflected in recent clinical practice guidelines [8, 27, 28]. Despite such recommendations and clear clinical need, available support services are often minimal for patients with pancreatic cancer and their families [6].

The Wallace McCain Centre for Pancreatic Cancer (WMCPC) was established in 2013 at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM) in Toronto, Canada to advance the quality of care provided for this population and to develop new and innovative ways to improve outcomes and reduce the burden of disease. The WMCPC provided a unique opportunity to develop an improved model for the delivery of psychosocial care as part of usual oncology care. This center offers a comprehensive interprofessional and multidisciplinary clinic that promotes early referral to specialized psychosocial and palliative care services. Although formulating a comprehensive treatment plan is important to patients and their families, an early psychoeducational intervention in this context could also be of value to provide information and support and to promote the use of such evidence-based specialized services.

Involving stakeholders

The success of the development and implementation process of an intervention depends on the early involvement of key stakeholders [23, 24]. This ensures clinical relevance and commitment, and engages champions within the organization to take leadership and responsibility for sustainability. We therefore recruited an interdisciplinary team from the pancreatic oncology and supportive care clinics at our comprehensive cancer center to develop the intervention. The content developers included representatives from nursing, an oncology clinical nurse specialist (CNS) (n = 1, SM), social work (n = 2, KA, AH), dietetics (n = 1, SB), and psychology (n = 1, CL). An expert from patient education (n = 1, LL) ensured that the language and presentation of information were appropriate for individuals with different educational backgrounds. Implementation support was provided by research administration (n = 5, ET, AR, AD, SC, AF) and clinical administration (n = 1, VK). Conceptual oversight was provided by representatives from psychology (n = 1, GMD), psychiatry (n = 1, GR), palliative care (n = 1, CZ), and oncology (n = 1, SG). These stakeholders were involved from the time of project conception and participated in group and individual meetings to develop the intervention from September 2016 to September 2017.

Assessing available resourcing

The CNS, social worker, and dietitian from our team agreed to deliver the intervention jointly, with each taking primary responsibility for his or her area of expertise. As part of usual care, these professionals had been providing individualized assessments and care regarding pain and symptoms, nutrition, advance care planning, and how to live well with pancreatic cancer. However, they recognized the greater efficiency of a group format and the potential value of working together to deliver the psychoeducational intervention [19]. A group intervention format was considered to be the most clinically feasible and cost- and time-efficient to provide information to patients and families. Group psychoeducational interventions can also help normalize circumstances of disease and reduce uncertainties of the future, by talking to others in a similar situation [29], and have been used to support both patients and caregivers affected by cancer [19, 30, 31]. The ongoing role of the team members within the WMCPC would also allow the intervention to be sustained subsequently as part of routine care. Early consultation with these professionals suggested compatibility between their perceived clinical roles and the goals of the intervention. As we continued to develop the intervention and to conduct practice sessions, the team became increasingly more invested in and felt shared ownership of this implementation effort. Such strengthening of interpersonal ties has been found to be necessary for sustainable implementation [32].

There was debate during the development process about the intervention “dose,” or the number of sessions needed for optimal clinical benefit. The degree of benefit people obtain from psychosocial interventions is typically associated with the number of sessions they receive [20], but this also may increase the costs and burden of delivery and participation. For this reason, low-intensity designs are increasingly adopted in stepped-care models of psychological care, to provide services efficiently that respond to need, to improve access and maximize cost-effectiveness [23, 33]. This includes brief single session psychoeducational interventions, which have shown benefits in relation to knowledge, preparedness, and unmet needs, and may have greater potential for sustainability [30, 31]. Balancing these factors, we created an intervention prototype consisting of a single session lasting 1.5 h. The first hour focused on delivering content; the last half hour was reserved for questions. We offered the intervention on a rotating, biweekly basis to accommodate space and time constraints. This low-intensity model could be integrated easily into the flow of usual care.

Establishing the evidence base for the content of the intervention

Considerable evidence demonstrates that patients with advanced cancers experience a range of physical and psychosocial challenges [7, 34]. In pancreatic cancer, these include: (1) problems with digestion and diet, poor appetite, and rapid weight loss [35]; (2) physical symptoms such as abdominal and back pain, nausea, jaundice, and diarrhea [36, 37]; (3) fears and concerns about the future [38]; and (4) adaptation to the impact of progressive disease on self and close others [39,40,41]. The encouragement of open communication and partnership with the health care team early in the disease trajectory improves symptom management and end-of-life outcomes, and can facilitate timely and appropriate referral and acceptance of specialized psychosocial and palliative care services [42,43,44].

The experience of cancer affects not only patients, but also their intimate others [45]. Family members fulfill many important caregiving duties for their loved ones affected by a cancer diagnosis, yet their roles and unique supportive care needs are often underestimated. Without adequate support, the burden of caregiving and worry about losing a loved one can lead to poor health and distress [5, 46, 47], especially as the disease progresses [48]. Supportive interventions that treat patients and their families as a single group implicitly acknowledge interdependencies among members of the family system [49], which is consistent with the principles of palliative care [27].

Tailoring the intervention

We designed the intervention to welcome all interested loved ones to attend with the patient. It was designed to be easily comprehensible to a wide audience without overwhelming participants with detail. The script was phrased in plain language with a Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) score of 65.1% [50] and Flesch-Kincaid reading grade level of 8.8 [51], indicating an eighth-grade reading level. The group format and circular seating arrangement of the group were chosen to encourage interactive discussion among attendees and facilitators, allowing for interjections and requests for clarification throughout the session. We included print handouts for note-taking to reduce the burden of recall. We focused on building a sense of trust and rapport with the health care team and offered to meet for individualized consults post-session.

Our interdisciplinary team of stakeholders reviewed the literature to generate an initial list of topics for the intervention. Upon further team consultation and refinement, we arrived at our key content areas. They were chosen to comprehensively address the range of concerns as identified in the literature and from clinical experience (see Table 1 for key content areas and main discussion points). These areas were related to the physical effects of pancreatic cancer, its impact on psychological and social wellbeing, ways to address those impacts (e.g., communication and planning for the end of life), and resources that can provide additional support. Generation of key content areas was followed by the development of a treatment manual for Living Well with Pancreatic Cancer [see Additional file 2]. Participants received a folder that included printed slides, informational pamphlets, and details about hospital network- and community-based programs that provide relevant support. The first author (ET) and education specialist (LL) assembled the PowerPoint presentation and developed the accompanying script to ensure the quality of content and design. In particular, they emphasized the use of plain language, readability, and developed an appropriate layout that included both text and graphic content.

The delivery of the intervention was tailored to broach difficult topics in a supportive and non-threatening way. Our team acknowledged the urgency and perceived threat of discussions of advance care planning and palliative care for this population. Therefore, the order in which topics were introduced was organized to commence with material that was more practical and then to proceed to more future-oriented topics associated with living with advanced cancer. The intervention first addressed practical issues involving nutrition and self-management of symptoms, including tips on how to eat and maintain weight during treatment, pain management, bowel movements, and how to cope with disease and treatment-induced nausea using both dietary and medication monitoring. This was followed by information about palliative care and advance care planning. To dispel myths surrounding the term palliative care, we defined it as focusing on improving the quality of life in patients and families, and including pain and symptom management for individuals at any age or point in the illness trajectory, regardless of the course of treatment, aligning with recent clinical recommendations [14, 52]. We explained that adapting to advanced disease requires engaging in and living life meaningfully, while simultaneously planning and preparing for all eventualities, including death. This challenge was described as similar to following two, divergent paths at the same time. This analogy of a “double road” or “double awareness” has been found to be clinically useful [53,54,55].

The last issues to be discussed were the impact of cancer on patients and their families, and available supportive-care services, including hospital-based services (e.g., social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, spiritual care workers, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, psychotherapy tailored for advanced cancer [56], and community-based services (e.g., Gilda’s Club, Wellspring, Canadian Cancer Society, Pancreatic Cancer Canada, Craig’s Cause Pancreatic Cancer Society). We emphasized that patients and families face illness together, and discussed both the importance and difficulty of sustaining open communication about physical, emotional, and existential concerns when they arise. Attendees were encouraged to seek and accept help from others. Throughout the session, we sought to engage patients and family in honest, supportive dialog as a demonstration of the value of professional support [57].

Planning for a formative evaluation

To assess the success of our implementation effort and to provide strategic information that may guide its further improvement, the intervention described in this paper is currently being tested in a feasibility study using a mixed-methods approach. Outcomes include the rate of referral to the intervention and number of patients and loved ones who attend; interview feedback from attendees about the timing, acceptability, and value of the intervention, and their suggestions for its improvement; and feedback from health care providers in the clinic about the process and feasibility of intervention implementation. This study will aim to characterize the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and its implementation process in an ambulatory pancreatic oncology clinic at a large tertiary cancer center.

Summary

We report here on the stepwise development of an interdisciplinary-led, group psychoeducational intervention to meet the informational and supportive care needs of individuals affected by pancreatic cancer. Living Well with Pancreatic Cancer was developed by embedded health care professionals and based on their clinical experiences, the research literature, and implementation considerations. We hope that this paper may aid potential replication efforts and be helpful to other researchers seeking similar endeavors. We look forward to reporting the feasibility results when they become available.

Living with pancreatic cancer is highly challenging for both patients and their loved ones. It may epitomize the general public’s worst fears about having cancer because of its sudden onset, limited treatment options and effectiveness, and rapid course of deterioration. Given the current poor rate of survival for most patients with this disease, there is an urgent need to continue to promote adaptation and preparation and to provide support for patients as soon as possible after diagnosis. Living Well with Pancreatic Cancer is consistent with guidelines to provide early, dedicated palliative, and supportive care concurrently with oncology care to improve the overall standard of care [8]. Its implementation into routine practice disseminates knowledge and promotes reflection about the foreseeable physical and psychosocial concerns that arise over the course of this illness. Psychoeducation may constitute the first line of supportive intervention, with more specialized individual treatment provided subsequently within a stepped-care framework or tiered model of supportive care delivery [58].

Conclusion

The present study describes the development of an interdisciplinary-led intervention to support patients and caregivers following a recent diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. We considered implementation science principles during intervention development, to promote future uptake and sustainability in the clinical setting. This approach can be used to inform the design and implementation of similar initiatives to support people affected by other diseases with limited prognoses.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The intervention manual is submitted as Additional file 1 for publication.

Abbreviations

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CNS:

-

Clinical nurse specialist

- FRE:

-

Flesch Reading Ease

- HCP:

-

Health care provider

- TIDieR:

-

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

- WMCPC:

-

Wallace McCain Centre for Pancreatic Cancer

References

Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017.

Clark KL, Loscalzo M, Trask PC, Zabora J, Philip EJ. Psychological distress in patients with pancreatic cancer—an understudied group. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1313–20.

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28.

Janda M, Neale RE, Klein K, O’Connell DL, Gooden H, Goldstein D, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in people with pancreatic cancer and their carers. Pancreatology. 2017;17:321–7.

Beesley VL, Janda M, Goldstein D, Gooden H, Merrett ND, O’Connell DL, et al. A tsunami of unmet needs: pancreatic and ampullary cancer patients’ supportive care needs and use of community and allied health services. Psychooncology. 2016;25:150–7.

Gooden H, Tiller K, Mumford J, White K. Integrated psychosocial and supportive care needed for patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Forum. 2016;40:66–9.

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Smith TJ. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:119–22.

Fann JR, Ell K, Sharpe M. Integrating psychosocial care into cancer services. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1178–86.

Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, Rodin GM, Le LW, Zimmermann C. Referral practices of oncologists to specialized palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4380–6.

Ahmed N, Bestall J, Ahmedzai SH, Payne S, Clark D, Noble B. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Pall Med. 2004;18:525–42.

Ellis J, Lin J, Walsh A, Lo C, Shepherd FA, Moore M, et al. Predictors of referral for specialized psychosocial oncology care in patients with metastatic cancer: the contributions of age, distress, and marital status. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:699–705.

Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4013–7.

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Leighl N, Rydall A, Rodin G, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ. 2016;188:E217–27.

Hui D, Elsayem A, De La Cruz M, Berger A, Zhukovsky DS, Palla S, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–61.

Sagar SM. Integrative oncology: are we doing enough to integrate psycho-education? Future Oncol. 2016;12:2779–83.

Garchinski CM, DiBiase A-M, Wong RK, Sagar SM. Patient-centered care in cancer treatment programs: the future of integrative oncology through psychoeducation. Future Oncol. 2014;10:2603–14.

Thompson AL, Young-Saleme TK. Anticipatory guidance and psychoeducation as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:S684–93.

Zimmermann T, Heinrichs N, Baucom DH. “Does one size fit all?” moderators in psychosocial interventions for breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:225–39.

Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:782–93.

Wang F, Luo D, Fu L, Zhang H, Wu S, Zhang M, et al. The efficacy of couple-based interventions on health-related quality of life in Cancer patients and their spouses: a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:39–47.

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1.

Schofield P, Chambers S. Effective, clinically feasible and sustainable. Key design features of psycho-educational and supportive care interventions to promote individualised self-management in cancer care. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:805–12.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, Bowman C, Guihan M, Hagedorn H, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S1–8.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance: World Health Organization; 2014. www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf

Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Kwete XJ, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391–454.

Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Arndt LA, Pasnau RO. Critical review of psychosocial interventions in cancer care. Arch Gen Psych. 1995;52:100–13.

Hudson PL, Trauer T, Lobb E, Zordan R, Williams A, Quinn K, et al. Supporting family caregivers of hospitalised palliative care patients: a psychoeducational group intervention. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2:115–20.

Jones JM, Cheng T, Jackman M, Walton T, Haines S, Rodin G, et al. Getting back on track: evaluation of a brief group psychoeducation intervention for women completing primary treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:117–24.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629.

Chambers SK, Hutchison S, Clutton S, Dunn J. Intervening to improve psychological outcomes after cancer: what is known and where next? Aust Psychol. 2014;49:96–103.

Muircroft W, Currow D. Palliative care in advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Forum. 2016;40:62–5.

Tang C-C, Von AD, Fulton JS. The symptom experience of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: an integrative review. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:33–44.

Labori KJ, Hjermstad MJ, Wester T, Buanes T, Loge JH. Symptom profiles and palliative care in advanced pancreatic cancer—a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1126–33.

Kanji ZS, Gallinger S. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer. CMAJ. 2013;185:1219–26.

Tong E, Deckert A, Gani N, Nissim R, Rydall A, Hales S, et al. The meaning of self-reported death anxiety in advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2016;30:772–9.

Rodin G, Lo C, Mikulincer M, Donner A, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C. Pathways to distress: the multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:562–9.

Lo C, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, Walsh A, Jones JM, Moore MJ, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3084–9.

Rodin G, Gillies L. Individual psychotherapy for the patient with advanced disease. In: Chochinov HM, Breitbart W, editors. Handbook of psychiatry in palliative medicine. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 443–53.

Greer JA, Jackson VA, Meier DE, Temel JS. Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:349–62.

Wittenberg-Lyles E, Goldsmith J, Ragan S. The shift to early palliative care: a typology of illness journeys and the role of nursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:304–10.

Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003.

Veach TA, Nicholas DR, Barton MA. Cancer and the family life cycle: a practitioner’s guide. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 2013.

Sharpe L, Butow P, Smith C, McConnell D, Clarke S. The relationship between available support, unmet needs and caregiver burden in patients with advanced cancer and their carers. Psychooncology. 2005;14:102–14.

Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4829–34.

Dumont S, Turgeon J, Allard P, Gagnon P, Charbonneau C, Vézina L. Caring for a loved one with advanced cancer: determinants of psychological distress in family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:912–21.

Lo C, Hales S, Braun M, Rydall AC, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Couples facing advanced cancer: examination of an interdependent relational system. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2283–90.

Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:221–3.

Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP Jr, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Research Branch Report 8–75. Millington: Naval Air Station; 1975.

Zwakman M, Jabbarian LJ, van Delden JJ, van der Heide A, Korfage IJ, Pollock K, et al. Advance care planning: a systematic review about experiences of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness. Palliat Med. 2018;32:1305–21.

Rodin G, Zimmermann C. Psychoanalytic reflections on mortality: a reconsideration. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2008;36:181–96.

Jacobsen J, Brenner K, Greer JA, Jacobo M, Rosenberg L, Nipp RD, et al. When a patient is reluctant to talk about it: a dual framework to focus on living well and tolerate the possibility of dying. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:322–7.

MacArtney JI, Broom A, Kirby E, Good P, Wootton J. The liminal and the parallax: living and dying at the end of life. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:623–33.

Rodin G, Lo C, Rydall A, Shnall J, Malfitano C, Chiu A, et al. Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): A randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2422–32.

Thorne S, Hislop TG, Kim-Sing C, Oglov V, Oliffe JL, Stajduhar KI. Changing communication needs and preferences across the cancer care trajectory: insights from the patient perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1009–15.

Hutchison SD, Steginga SK, Dunn J. The tiered model of psychosocial intervention in cancer: a community based approach. Psychooncology. 2006;15:541–6.

Acknowledgements

We received valuable input and support at each stage of development from other team members including Anne Rydall, Louise Lee, Ali Henderson, Anna Dodd, Sean Creighton, and Adriana Fraser.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation Harold and Shirley Lederman Chair Income Fund and the Al Hertz Fund (GR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ET was the major contributor towards the article, including oversight of intervention development and corresponding author for this report. CL and GR contributed to the design, conduct, and write-up of the study. SM, KA, and SB were the clinical representative leads that contributed to the development of the intervention. VK advised on the administrative aspects of implementation in practice. CL, GR, GMD, CZ, and SG advised on the clinical and research aspects of the intervention. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

All co-authors consent to submit this manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Completed TIDieR Checklist. (PDF 57 kb)

Additional file 2:

Living Well with Pancreatic Cancer Intervention Manual. (PDF 945 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, E., Lo, C., Moura, S. et al. Development of a psychoeducational intervention for people affected by pancreatic cancer. Pilot Feasibility Stud 5, 80 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0466-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0466-x